Advancements in Functional Dressings and a Case for Cotton Fiber Technology: Protease Modulation, Hydrogen Peroxide Generation, and ESKAPE Pathogen Antibacterial Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Toward Intelligent Dressing Treatments

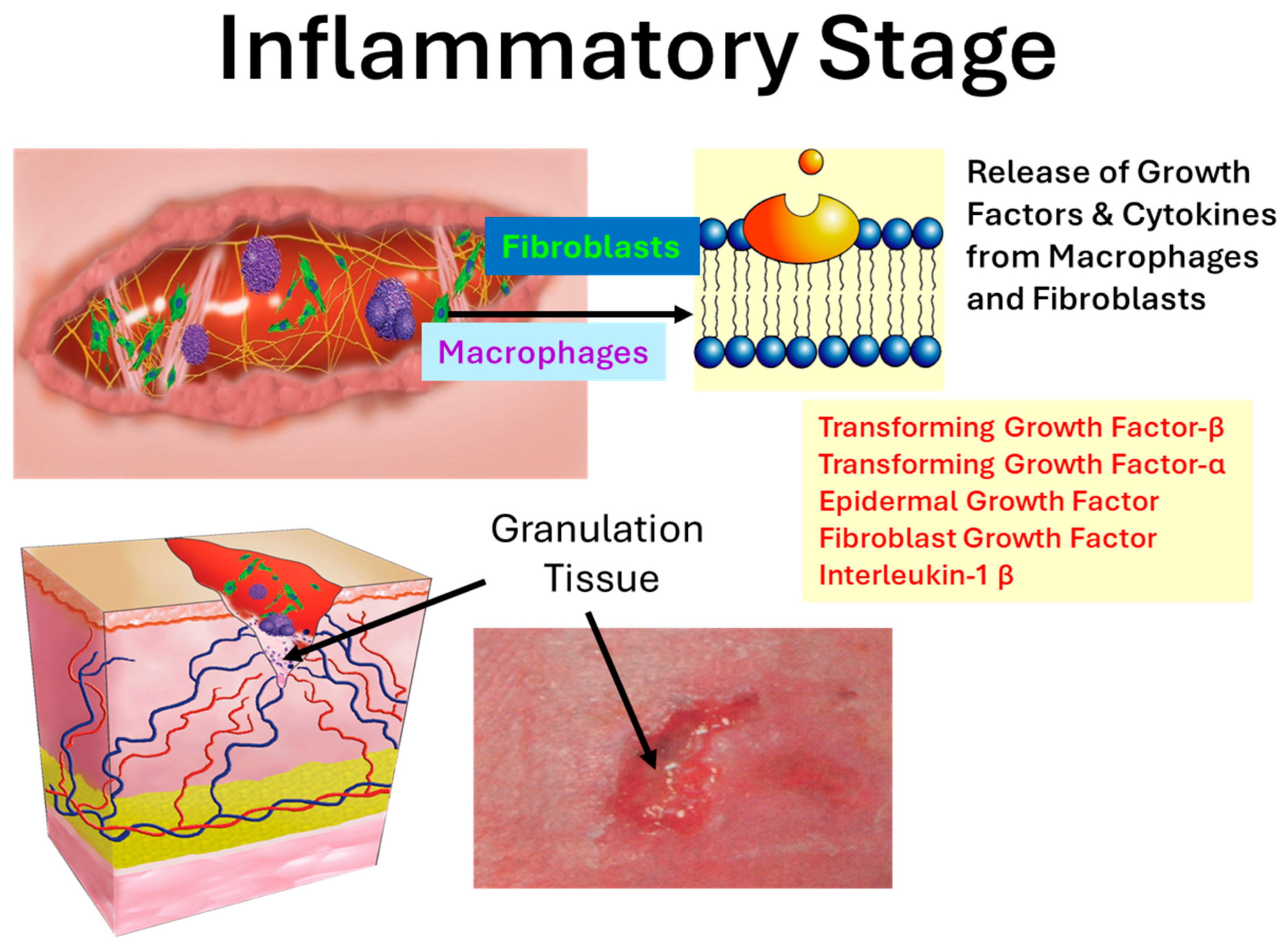

1.2. The Inflammatory Phase and Protease Burden

1.3. Chronic Wound Protease Modulating Dressings

1.4. Hydrogen Peroxide and Wound Healing

1.5. ESKAPE Pathogens and Wound Dressings

2. Results

2.1. Protease Modulation

2.2. Composite Matrix Dressing

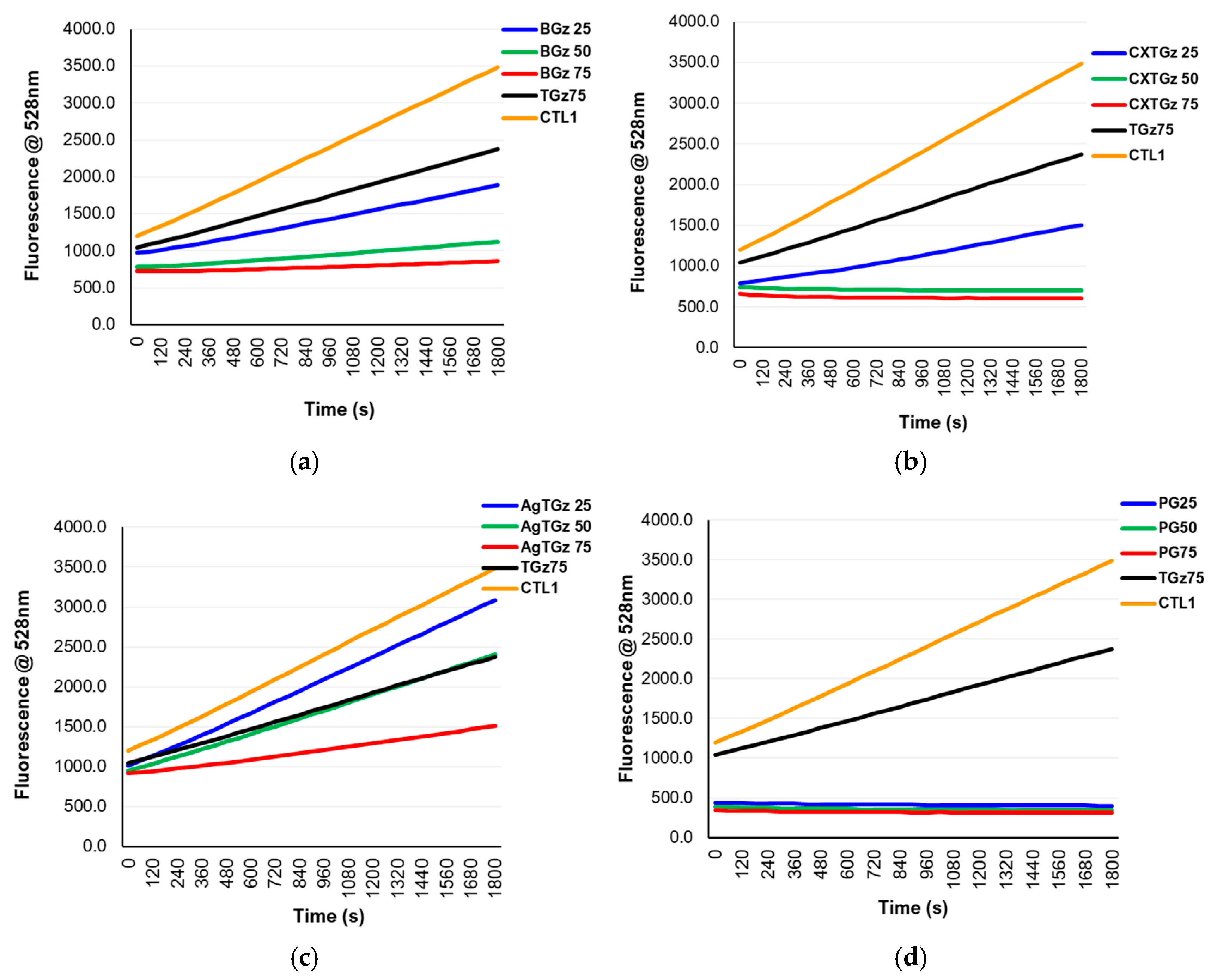

2.3. Hydrogen Peroxide

2.4. Antimicrobial Activity of Treated TGz: “ESKAPE” Model

3. Discussion

3.1. Clinically Relevant Studies on Other Types of Protease Modulation Dressings: Films, Foams and Hydrogels

3.2. Cotton-Based Dressings with Multiple Functionality

Hydrogen Peroxide Generation and Protease Modulation

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Enzyme Assays

4.2.1. Elastase Assay

4.2.2. Collagenase Assay

4.3. Hydrogen Peroxide Assay

4.4. Antibacterial Testing of Fabric

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lindley, L.E.; Stojadinovic, O.; Pastar, I.; Tomic-Canic, M. Biology and Biomarkers for Wound Healing. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 138, 18S–28S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prame Kumar, K.; Nicholls, A.J.; Wong, C.H.Y. Partners in crime: Neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in inflammation and disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2018, 371, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongarora, B.G. Recent technological advances in the management of chronic wounds: A literature review. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, M.; Järbrink, K.; Divakar, U.; Bajpai, R.; Upton, Z.; Schmidtchen, A.; Car, J. The humanistic and economic burden of chronic wounds: A systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2019, 27, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrientos, S.; Stojadinovic, O.; Golinko, M.S.; Brem, H.; Tomic-Canic, M. PERSPECTIVE ARTICLE: Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008, 16, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, G.S.; Wysocki, A. Interactions between extracellular matrix and growth factors in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2009, 17, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, G.S.; Davidson, J.M.; Kirsner, R.S.; Bornstein, P.; Herman, I.M. Dynamic reciprocity in the wound microenvironment. Wound Repair Regen. 2011, 19, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trengove, N.J.; Stacey, M.C.; MacAuley, S.; Bennett, N.; Gibson, J.; Burslem, F.; Murphy, G.; Schultz, G. Analysis of the acute and chronic wound environments: The role of proteases and their inhibitors. Wound Repair Regen. 1999, 7, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, D.R.; Nwomeh, B.C. The proteolytic environment of chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 1999, 7, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinnell, F.; Zhu, M. Identification of Neutrophil Elastase as the Proteinase in Burn Wound Fluid Responsible for Degradation of Fibronectin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1994, 103, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, S.M.; Cochrane, C.A.; Clegg, P.D.; Percival, S.L. The role of endogenous and exogenous enzymes in chronic wounds: A focus on the implications of aberrant levels of both host and bacterial proteases in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2012, 20, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, B.; Smith, R.; McCulloch, E.; Silcock, D.; Morrison, L. Mechanism of action of PROMOGRAN, a protease modulating matrix, for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2002, 10, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.V.; Bopp, A.F.; Batiste, S.; Ullah, A.J.; Cohen, K.I.; Diegelmann, R.F.; Montante, S.J. Inhibition of elastase by a synthetic cotton-bound serine protease inhibitor: In vitro kinetics and inhibitor release. Wound Repair Regen. 1999, 7, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.V.; Yager, D.R.; Cohen, I.K.; Diegelmann, R.F.; Montante, S.; Bertoniere, N.; Bopp, A.F. Modified cotton gauze dressings that selectively absorb neutrophil elastase activity in solution. Wound Repair Regen. 2001, 9, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.B.; Lam, K.; Buret, A.G.; Olson, M.E.; Burrell, R.E. Early healing events in a porcine model of contaminated wounds: Effects of nanocrystalline silver on matrix metalloproteinases, cell apoptosis, and healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2002, 10, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahreez, D.; Ghasemi-Mobarakeh, L.; Liebner, F.; Alihosseini, F.; Quartinello, F.; Guebitz, G.M.; Ribitsch, D. Approaches to Control and Monitor Protease Levels in Chronic Wounds. Adv. Ther. 2024, 7, 2300396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.V.; Howley, P.; Cohen, I.K. In vitro inhibition of human neutrophil elastase by oleic acid albumin formulations from derivatized cotton wound dressings. Int. J. Pharm. 2004, 284, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, C.R.; Favoreto, S., Jr.; Oliveira, L.L.; Vancim, J.O.; Barban, G.B.; Ferraz, D.B.; Silva, J.S. Oleic acid modulation of the immune response in wound healing: A new approach for skin repair. Immunobiology 2011, 216, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, G.B.; Chacon, E.; Chacon, P.G.; Bordeaux-Rego, P.; Duarte, A.S.; Saad, S.T.O.; Zavaglia, C.A.; Cunha, M.R. Fatty acid is a potential agent for bone tissue induction: In vitro and in vivo approach. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 242, 1765–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.G. Redox signaling: Hydrogen peroxide as intracellular messenger. Exp. Mol. Med. 1999, 31, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Khanna, S.; Nallu, K.; Hunt, T.K.; Sen, C.K. Dermal wound healing is subject to redox control. Mol. Ther. 2006, 13, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, C.K.; Roy, S. Redox signals in wound healing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gen. Subj. 2008, 1780, 1348–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, T. Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 194, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niethammer, P.; Grabher, C.; Look, A.T.; Mitchison, T.J. A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature 2009, 459, 996–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, Q.; Lu, S.; Niu, Y. Hydrogen peroxide: A potential wound therapeutic target. Med. Princ. Pract. 2017, 26, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Chung, L.; Turner, T. Quantification of hydrogen peroxide generation by Granuflex™(DuoDERM™) Hydrocolloid Granules and its constituents (gelatin, sodium carboxymethylcellulose, and pectin). Br. J. Dermatol. 1993, 129, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, J.; Ghatak, P.D.; Roy, S.; Khanna, S.; Hemann, C.; Deng, B.; Das, A.; Zweier, J.L.; Wozniak, D.; Sen, C.K. Silver-zinc redox-coupled electroceutical wound dressing disrupts bacterial biofilm. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, A.C.; Gil, J.; Valdes, J.; Solis, M.; Davis, S.C. Efficacy of a bio-electric dressing in healing deep, partial-thickness wounds using a porcine model. Ostomy/Wound Manag. 2012, 58, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana, S.T.; Atci, E.; Babauta, J.T.; Mohamed Falghoush, A.; Snekvik, K.R.; Call, D.R.; Beyenal, H. Electrochemical scaffold generates localized, low concentration of hydrogen peroxide that inhibits bacterial pathogens and biofilms. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Arias, C.A. ESKAPE pathogens: Antimicrobial resistance, epidemiology, clinical impact and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.V.; Prevost, N.T.; Hinchliffe, D.J.; Nam, S.; Chang, S.; Hron, R.J.; Madison, C.A.; Smith, J.N.; Poffenberger, C.N.; Taylor, M.M.; et al. Preparation and Activity of Hemostatic and Antibacterial Dressings with Greige Cotton/Zeolite Formularies Having Silver and Ascorbic Acid Finishes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Griffiths, P.T.; Campbell, S.J.; Utinger, B.; Kalberer, M.; Paulson, S.E. Ascorbate oxidation by iron, copper and reactive oxygen species: Review, model development, and derivation of key rate constants. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerling, K.A.; Kersey, A.J.; Lauria, A.L.; Mares, J.A.; Hutzler, J.D.; White, P.W.; Abel, B.; Burmeister, D.M.; Propper, B.; White, J.M. Evaluation of novel hemostatic agents in a coagulopathic swine model of junctional hemorrhage. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 2023, 95, S144–S151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajmir-Riahi, H.A. Coordination chemistry of vitamin C. Part II. Interaction of L-ascorbic acid with Zn(II), Cd(II), Hg(II), and Mn(II) ions in the solid state and in aqueous solution. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1991, 42, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donato-Trancoso, A.; de Carvalho Faria, R.V.; de S. Ribeiro, B.C.; Nogueira, J.S.; Atella, G.C.; Chen, L.; Romana-Souza, B. Dual effects of extra virgin olive oil in acute wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2023, 31, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.V.; Howley, P.; Yachmenev, V.; Lambert, A.; Condon, B. Development of a continuous finishing chemistry process for manufacture of a phosphorylated cotton chronic wound dressing. J. Ind. Text. 2009, 39, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, D.J.; Yager, D.R. Novel sulfonated hydrogel composite with the ability to inhibit proteases and bacterial growth. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2006, 76A, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarlton, J.F.; Munro, H.S. Use of modified superabsorbent polymer dressings for protease modulation in improved chronic wound care. Wounds 2013, 25, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, S.; Song, L.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, K.; Jiang, L.; He, H.; Lin, C.; Wu, J. Zwitterionic Hydrogel Activates Autophagy to Promote Extracellular Matrix Remodeling for Improved Pressure Ulcer Healing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 740863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majtan, J.; Jesenak, M. β-Glucans: Multi-Functional Modulator of Wound Healing. Molecules 2018, 23, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woundcare Handbook: Protease Modulating Dressings. Available online: https://www.woundcarehandbook.com/configuration/categories/wound-care/protease-modulators/protease-modulators/ (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Christoforou, C.; Lin, X.; Bennett, S.; Connors, D.; Skalla, W.; Mustoe, T.A.; Linehan, J.; Arnold, F.; Gruskin, E.A. Biodegradable positively charged ion exchange beads: A novel biomaterial for enhancing soft tissue repair. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998, 42, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, D.; Gies, D.; Lin, H.; Gruskin, E.; Mustoe, T.A.; Tawil, N.J. Increase in wound breaking strength in rats in the presence of positively charged dextran beads correlates with an increase in endogenous transforming growth factor-β1 and its receptor TGF-βRI in close proximity to the wound. Wound Repair Regen. 2000, 8, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönfelder, U.; Abel, M.; Wiegand, C.; Klemm, D.; Elsner, P.; Hipler, U.C. Influence of selected wound dressings on PMN elastase in chronic wound fluid and their antioxidative potential in vitro. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 6664–6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobmann, R.; Zemlin, C.; Motzkau, M.; Reschke, K.; Lehnert, H. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and growth factors in diabetic foot wounds treated with a protease absorbent dressing. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2006, 20, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, M.; Dini, V.; Romanelli, P. Hydroxyurea-induced leg ulcers treated with a protease-modulating matrix. Arch. Dermatol. 2007, 143, 1310–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakagia, D.D.; Kazakos, K.J.; Xarchas, K.C.; Karanikas, M.; Georgiadis, G.S.; Tripsiannis, G.; Manolas, C. Synergistic action of protease-modulating matrix and autologous growth factors in healing of diabetic foot ulcers. A prospective randomized trial. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2007, 21, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloeters, O.; Unglaub, F.; de Laat, E.; van Abeelen, M.; Ulrich, D. Prospective and randomised evaluation of the protease-modulating effect of oxidised regenerated cellulose/collagen matrix treatment in pressure sore ulcers. Int. Wound J. 2016, 13, 1231–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, R.; Ulrich, D.; Unglaub, F.; Wöltje, M.; Pallua, N. Effect of oxidised regenerated cellulose/collagen matrix on proteases in wound exudate of patients with chronic venous ulceration. Int. Wound J. 2008, 5, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, D.; Smeets, R.; Unglaub, F.; Wöltje, M.; Pallua, N. Effect of oxidized regenerated cellulose/collagen matrix on proteases in wound exudate of patients with diabetic foot ulcers. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2011, 38, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.V.; Prevost, N.T.; Nam, S.; Hinchliffe, D.; Condon, B.; Yager, D. Induction of low-level hydrogen peroxide generation by unbleached cotton nonwovens as potential wound dressing materials. J. Funct. Biomater. 2017, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, S.C. Oxidative scission of plant cell wall polysaccharides by ascorbate-induced hydroxyl radicals. Biochem. J. 1998, 332, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweikert, C.; Liszkay, A.; Schopfer, P. Scission of polysaccharides by peroxidase-generated hydroxyl radicals. Phytochemistry 2000, 53, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kato, N.; Kim, S.; Triplett, B. Cu/Zn superoxide dismutases in developing cotton fibers: Evidence for an extracellular form. Planta 2008, 228, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, S.H.; Yoon, H.S.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, K.S. Efficacy of oxidized regenerated cellulose, SurgiGuard®, in porcine surgery. Yonsei Med. J. 2017, 58, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braccini, I.; Pérez, S. Molecular basis of Ca2+-induced gelation in alginates and pectins: The egg-box model revisited. Biomacromolecules 2001, 2, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoy, M.M.I.; Gelston, S.; Mohamed, A.; Flurin, L.; Raval, Y.S.; Greenwood-Quaintance, K.; Patel, R.; Lewandowski, Z.; Beyenal, H. Hypochlorous acid produced at the counter electrode inhibits catalase and increases bactericidal activity of a hydrogen peroxide generating electrochemical bandage. Bioelectrochemistry 2022, 148, 108261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raval, Y.S.; Fleming, D.; Mohamed, A.; Karau, M.J.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Schuetz, A.N.; Greenwood Quaintance, K.E.; Beyenal, H.; Patel, R. In Vivo Activity of Hydrogen-Peroxide Generating Electrochemical Bandage Against Murine Wound Infections. Adv. Ther. 2023, 6, 2300059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, J.; Das Ghatak, P.; Roy, S.; Khanna, S.; Sequin, E.K.; Bellman, K.; Dickinson, B.C.; Suri, P.; Subramaniam, V.V.; Chang, C.J.; et al. Improvement of human keratinocyte migration by a redox active bioelectric dressing. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zeng, W.; Xu, P.; Fu, X.; Yu, X.; Chen, L.; Leng, F.; Yu, C.; Yang, Z. Glucose-responsive multifunctional metal-organic drug-loaded hydrogel for diabetic wound healing. Acta Biomater. 2022, 140, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Liu, Y.Q.; Liu, P.; Cao, J.; Shen, A.G.; Chu, P.K. Blood-Glucose-Depleting Hydrogel Dressing as an Activatable Photothermal/Chemodynamic Antibacterial Agent for Healing Diabetic Wounds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 24162–24174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Hansen, E.N. Hydrogen peroxide wound irrigation in orthopaedic surgery. J. Bone Jt. Infect. 2017, 2, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, L.M.; Buntting, C.; Molan, P. The effect of dilution on the rate of hydrogen peroxide production in honey and its implications for wound healing. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2003, 9, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonks, A.J.; Cooper, R.; Jones, K.; Blair, S.; Parton, J.; Tonks, A. Honey stimulates inflammatory cytokine production from monocytes. Cytokine 2003, 21, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.V.; Chandrasekar, V.; Prabhu, V.M.; Bhadra, J.; Laux, P.; Bhardwaj, P.; Al-Ansari, A.A.; Aboumarzouk, O.M.; Luch, A.; Dakua, S.P. Sustainable bioinspired materials for regenerative medicine: Balancing toxicology, environmental impact, and ethical considerations. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 19, 060501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 17034:2016; General Requirements for the Competence of Reference Material Producers. The International Organization of Standardization: Vernier, Switzerland, 2016.

- Venkateswaran, P.; Vasudevan, S.; David, H.; Shaktivel, A.; Shanmugam, K.; Neelakantan, P.; Solomon, A.P. Revisiting ESKAPE Pathogens: Virulence, resistance, and combating strategies focusing on quorum sensing. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1159798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rojas, A.; Kim, J.J.; Johnston, P.R.; Makarova, O.; Eravci, M.; Weise, C.; Hengge, R.; Rolff, J. Non-lethal exposure to H2O2 boosts bacterial survival and evolvability against oxidative stress. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Hillyer, M.B.; Condon, B.D.; Lum, J.S.; Richards, M.N.; Zhang, Q. Silver Nanoparticle-Infused Cotton Fiber: Durability and Aqueous Release of Silver in Laundry Water. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 13231–13240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Hillyer, M.B.; He, Z.; Chang, S.; Edwards, J.V. Self-induced transformation of raw cotton to a nanostructured primary cell wall for a renewable antimicrobial surface. Nanoscale Adv. 2022, 4, 5404–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Hinchliffe, D.J.; Hillyer, M.B.; Gary, L.; He, Z. Washable Antimicrobial Wipes Fabricated from a Blend of Nanocomposite Raw Cotton Fiber. Molecules 2023, 28, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Yadav, V.B.; Yadav, U.; Nath, G.; Srivastava, A.; Zamboni, P.; Kerkar, P.; Saxena, P.S.; Singh, A.V. Evaluation of biogenic nanosilver-acticoat for wound healing: A tri-modal in silico, in vitro and in vivo study. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 670, 131575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigelt, M.A.; Lev-Tov, H.A.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Lee, W.D.; Williams, R.; Strasfeld, D.; Kirsner, R.S.; Herman, I.M. Advanced Wound Diagnostics: Toward Transforming Wound Care into Precision Medicine. Adv. Wound Care 2022, 11, 330–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, G.S.; Barillo, D.J.; Mozingo, D.W.; Chin, G.A. Wound bed preparation and a brief history of TIME. Int. Wound J. 2004, 1, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, G.D. Formation of the Scab and the Rate of Epithelization of Superficial Wounds in the Skin of the Young Domestic Pig. Nature 1962, 193, 293–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinman, C.D.; Maibach, H. Effect of Air Exposure and Occlusion on Experimental Human Skin Wounds. Nature 1963, 200, 377–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palamand, S.; Brenden, R.; Reed, A. Intelligent wound dressings and their physical characteristics. Wounds Compend. Clin. Res. Pract. 1992, 3, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Xia, H.; He, W.; Li, Z.; Zhao, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Lei, Q.; Kong, Y.; Bai, Y.; et al. Controlled water vapor transmission rate promotes wound-healing via wound re-epithelialization and contraction enhancement. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghazadeh, S.; Rinoldi, C.; Schot, M.; Kashaf, S.S.; Sharifi, F.; Jalilian, E.; Nuutila, K.; Giatsidis, G.; Mostafalu, P.; Derakhshandeh, H.; et al. Drug delivery systems and materials for wound healing applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 127, 138–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.-H.; Samandari, M.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Song, D.; Zhang, Y.; Tamayol, A.; Wang, X. Multimodal sensing and therapeutic systems for wound healing and management: A review. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2022, 4, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Soeranaya, B.H.T.; Truong, T.H.A.; Dang, T.T. Modular design of a hybrid hydrogel for protease-triggered enhancement of drug delivery to regulate TNF-α production by pro-inflammatory macrophages. Acta Biomater. 2020, 117, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nessler, M.B.; Puchała, J.; Chrapusta, A.; Nessler, K.; Drukała, J. Levels of plasma matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) in response to INTEGRA® dermal regeneration template implantation. Med. Sci. Monit. 2014, 20, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Dobson, G.P.; Davenport, L.M.; Morris, J.L.; Letson, H.L. The role of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and its inhibitor TIMP-1 in burn injury: A systematic review. Int. J. Burn. Trauma. 2021, 11, 275–288. [Google Scholar]

- Poteet, S.J.; Schulz, S.A.; Povoski, S.P.; Chao, A.H. Negative pressure wound therapy: Device design, indications, and the evidence supporting its use. Expert. Rev. Med. Devices 2021, 18, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.V.; Howley, P.S. Human neutrophil elastase and collagenase sequestration with phosphorylated cotton wound dressings. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2007, 83A, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stechmiller, J.K.; Kilpadi, D.V.; Childress, B.; Schultz, G.S. Effect of Vacuum-Assisted Closure Therapy on the expression of cytokines and proteases in wound fluid of adults with pressure ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2006, 14, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eming, S.; Smola, H.; Hartmann, B.; Malchau, G.; Wegner, R.; Krieg, T.; Smola-Hess, S. The inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase activity in chronic wounds by a polyacrylate superabsorber. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2932–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikosiński, J.; Kalogeropoulos, K.; Bundgaard, L.; Larsen, C.A.; Savickas, S.; Moldt Haack, A.; Pańczak, K.; Rybołowicz, K.; Grzela, T.; Olszewski, M.; et al. Longitudinal Evaluation of Biomarkers in Wound Fluids from Venous Leg Ulcers and Split-thickness Skin Graft Donor Site Wounds Treated with a Protease-modulating Wound Dressing. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2022, 102, adv00834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbert, P.; Faivre, B.; Véran, Y.; Debure, C.; Truchetet, F.; Bécherel, P.A.; Plantin, P.; Kerihuel, J.C.; Eming, S.A.; Dissemond, J.; et al. Protease-modulating polyacrylate-based hydrogel stimulates wound bed preparation in venous leg ulcers--a randomized controlled trial. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 28, 1742–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayment, E.A.; Upton, Z.; Shooter, G.K. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) activity observed in chronic wound fluid is related to the clinical severity of the ulcer. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 158, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minden-Birkenmaier, B.A.; Bowlin, G.L. Honey-Based Templates in Wound Healing and Tissue Engineering. Bioengineering 2018, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minden-Birkenmaier, B.A.; Meadows, M.B.; Cherukuri, K.; Smeltzer, M.P.; Smith, R.A.; Radic, M.Z.; Bowlin, G.L. The Effect of Manuka Honey on dHL-60 Cytokine, Chemokine, and Matrix-Degrading Enzyme Release under Inflammatory Conditions. Med. One 2019, 4, e190005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruwer, F. Medical Grade Honey Reduced Protease Activity and Promoted Wound Healing in Seven Patients with Non-Healing Wounds. Available online: https://www.woundcare-today.com/journals/issue/wound-care-today/article/medical-grade-honey-reduced-protease-activity-and-promoted-wound-healing-in-seven-patients-with-non-healing-wounds (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Edwards, J.V.; Graves, E.; Prevost, N.; Condon, B.; Yager, D.; Dacorta, J.; Bopp, A. Development of a Nonwoven Hemostatic Dressing Based on Unbleached Cotton: A De Novo Design Approach. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easson, M.; Edwards, J.V.; Mao, N.; Carr, C.; Marshall, D.; Qu, J.; Graves, E.; Reynolds, M.; Villalpando, A.; Condon, B. Structure/Function Analysis of Nonwoven Cotton Topsheet Fabrics: Multi-Fiber Blending Effects on Fluid Handling and Fabric Handle Mechanics. Materials 2018, 11, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veal, E.A.; Kritsiligkou, P. How are hydrogen peroxide messages relayed to affect cell signalling? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2024, 81, 102496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories, 3rd ed. The International Organization for Standardization and International Electrotechnical Commission: Vernier, Switzerland, 2017.

| Dressing | Example |

|---|---|

| Film | Tegaderm™, Opsite™ post-op |

| Foam | Allevyn™, Mepilex™ |

| NPWT a | Prevena™, Pico™ |

| Hydrogel | IntraSite, AquaSite® |

| Hydrocolloid | DuoDERM™ Signal, MediHoney, Exuderm |

| Alginate | Kaltostat®, Algisite-M |

| Composite/matrix | 3M™ Promogran Prisma® Matrix b |

| Sample | E. cloacae (13047) | S. aureus (6538) b | K. pneumoniae (4352) b | A. baumannii (19606) | P. aeruginosa (15442) | E. Faecium (0968) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGz | 99.17% 2.1 log10 reduct. | 94.31% c 1.2 log10 reduct. | 98.71% c 1.9 log10 reduct. | 98.83 1.9 log10 reduct. | 99.03 2 log10 reduct. | 98.44 1.8 log10 reduct. |

| BGz | >99.99% 7.2 log10 reduct. | >99.99%, nocr 5.3 log10 reduct. | >99.99%, nocr 6.2 log10 reduct. | >99.99% 6.6 log10 reduct. | 99.99% 3.9 log10 reduct. | >99.99% 7.3 log10 reduct. |

| CXTGz | >99.99% 7.2 log10 reduct. | >99.99%, nocr 5.3 log10 reduct. | >99.99%, nocr 6.2 log10 reduct. | >99.99% 5.3 log10 reduct. | >99.99% 4.9 log10 reduct. | >99.99% 7.3 log10 reduct. |

| AgTGz | 99.92% 3.1 log10 reduct. | >99.99%, nocr 5.3 log10 reduct. | >99.99%, nocr 6.2 log10 reduct. | 99.99% 3.9 log10 reduct. | 99.99% 3.9 log10 reduct. | 99.95% 3.3 log10 reduct. |

| CRM treated | 99.99 3.9 log10 reduct. | >99.99%, nocr 5.3 log10 reduct. | >99.99%, nocr 6.2 log10 reduct. | >99.99% 5.7 log10 reduct. | 99.94 3.2 log10 reduct. | 99.99 4.6 log10 reduct. |

| CRM UT ctrl | 1.41 × 108 CFU/sample | 1.8 × 106 CFU/sample | 1.42 × 107 CFU/sample | 2.78 × 108 CFU/sample | 2.52 × 108 CFU/sample | 1.8 × 108 CFU/sample |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Edwards, J.V.; Prevost, N.T.; Hinchliffe, D.J.; Nam, S.; Madison, C.A. Advancements in Functional Dressings and a Case for Cotton Fiber Technology: Protease Modulation, Hydrogen Peroxide Generation, and ESKAPE Pathogen Antibacterial Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020610

Edwards JV, Prevost NT, Hinchliffe DJ, Nam S, Madison CA. Advancements in Functional Dressings and a Case for Cotton Fiber Technology: Protease Modulation, Hydrogen Peroxide Generation, and ESKAPE Pathogen Antibacterial Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020610

Chicago/Turabian StyleEdwards, J. Vincent, Nicolette T. Prevost, Doug J. Hinchliffe, Sunghyun Nam, and Crista A. Madison. 2026. "Advancements in Functional Dressings and a Case for Cotton Fiber Technology: Protease Modulation, Hydrogen Peroxide Generation, and ESKAPE Pathogen Antibacterial Activity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020610

APA StyleEdwards, J. V., Prevost, N. T., Hinchliffe, D. J., Nam, S., & Madison, C. A. (2026). Advancements in Functional Dressings and a Case for Cotton Fiber Technology: Protease Modulation, Hydrogen Peroxide Generation, and ESKAPE Pathogen Antibacterial Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020610