Dissolving Silver Nanoparticles Modulate the Endothelial Monocyte-Activating Polypeptide II (EMAP II) by Partially Unfolding the Protein Leading to tRNA Binding Enhancement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Choice of Experimental Conditions

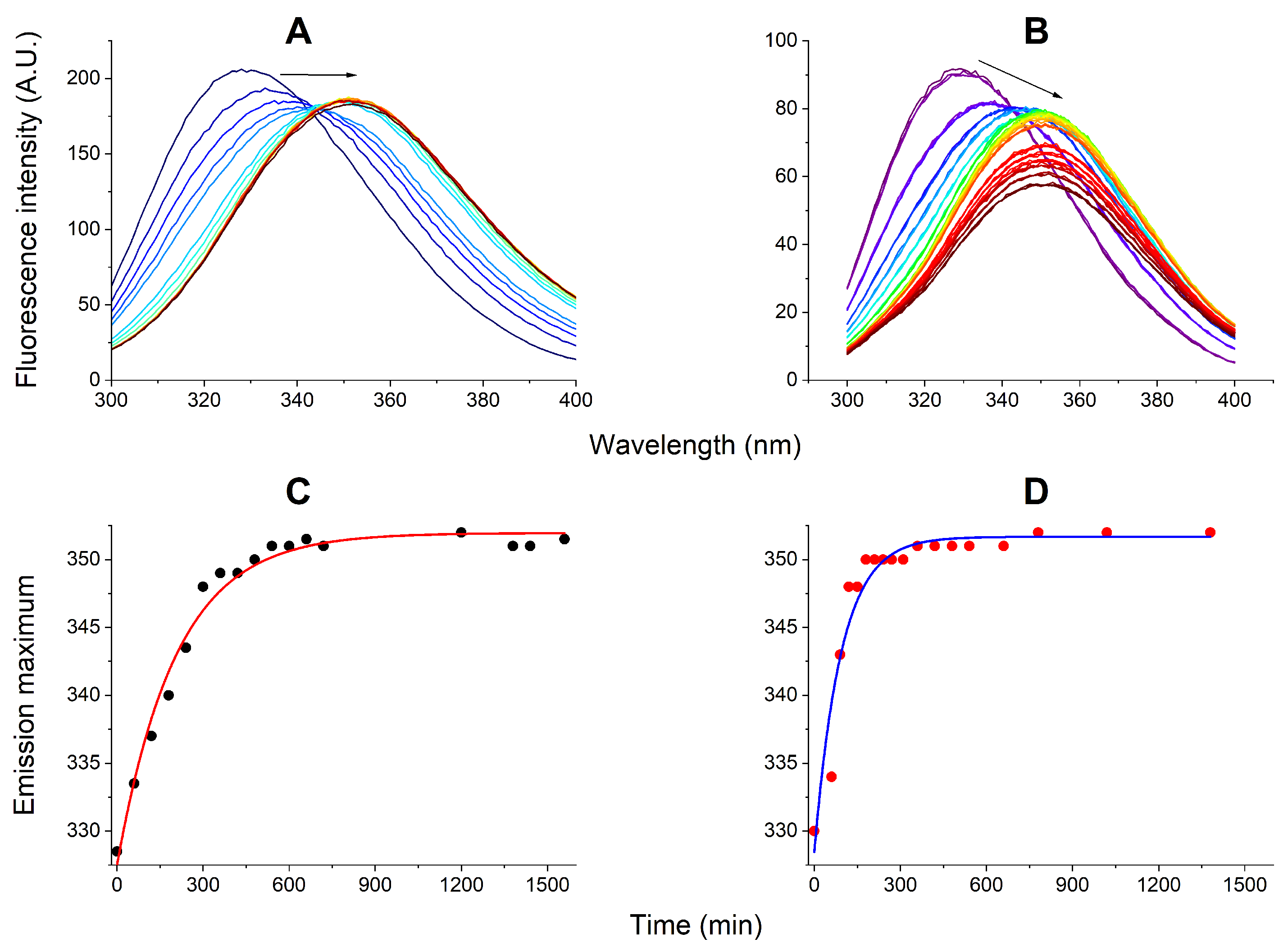

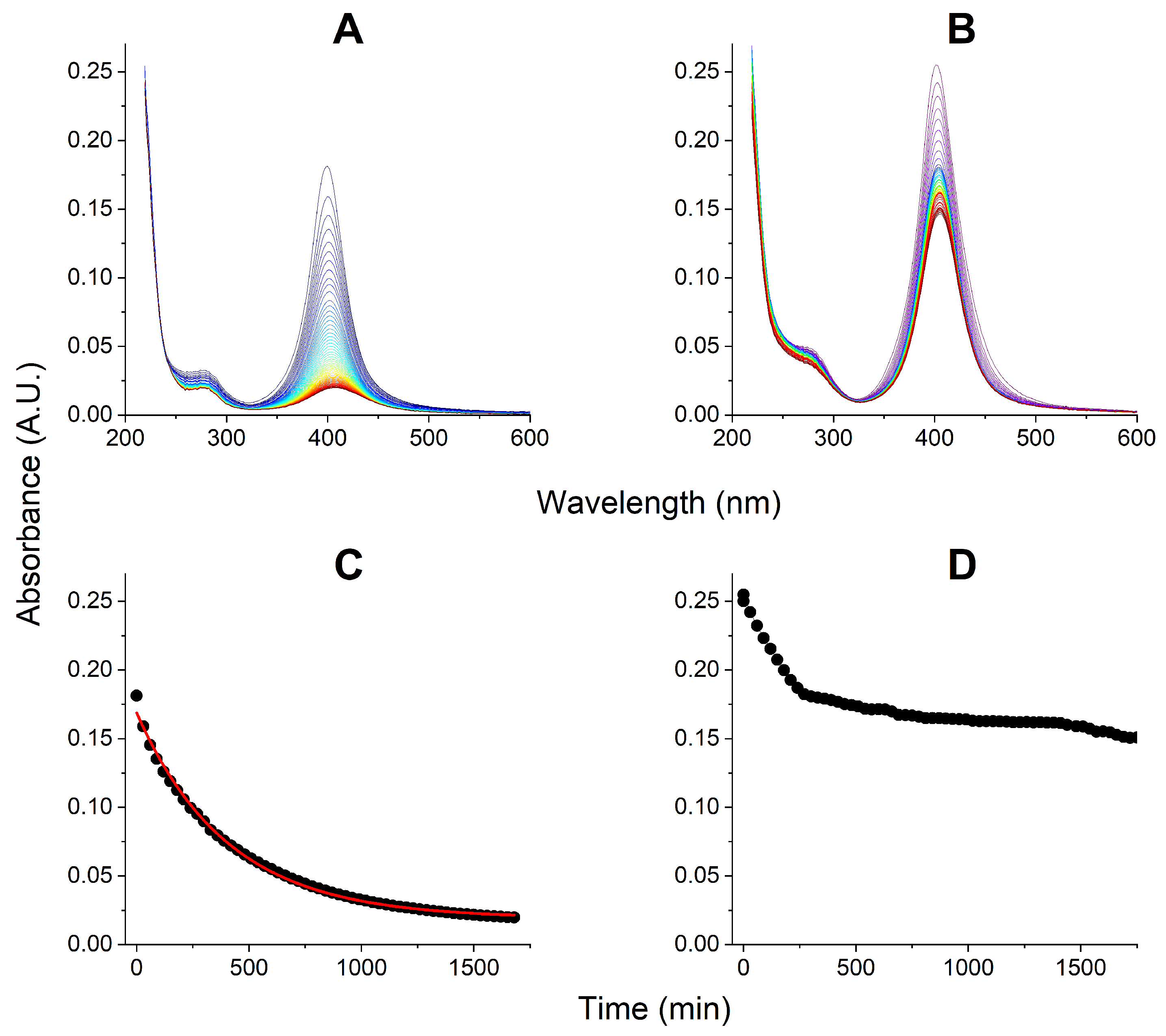

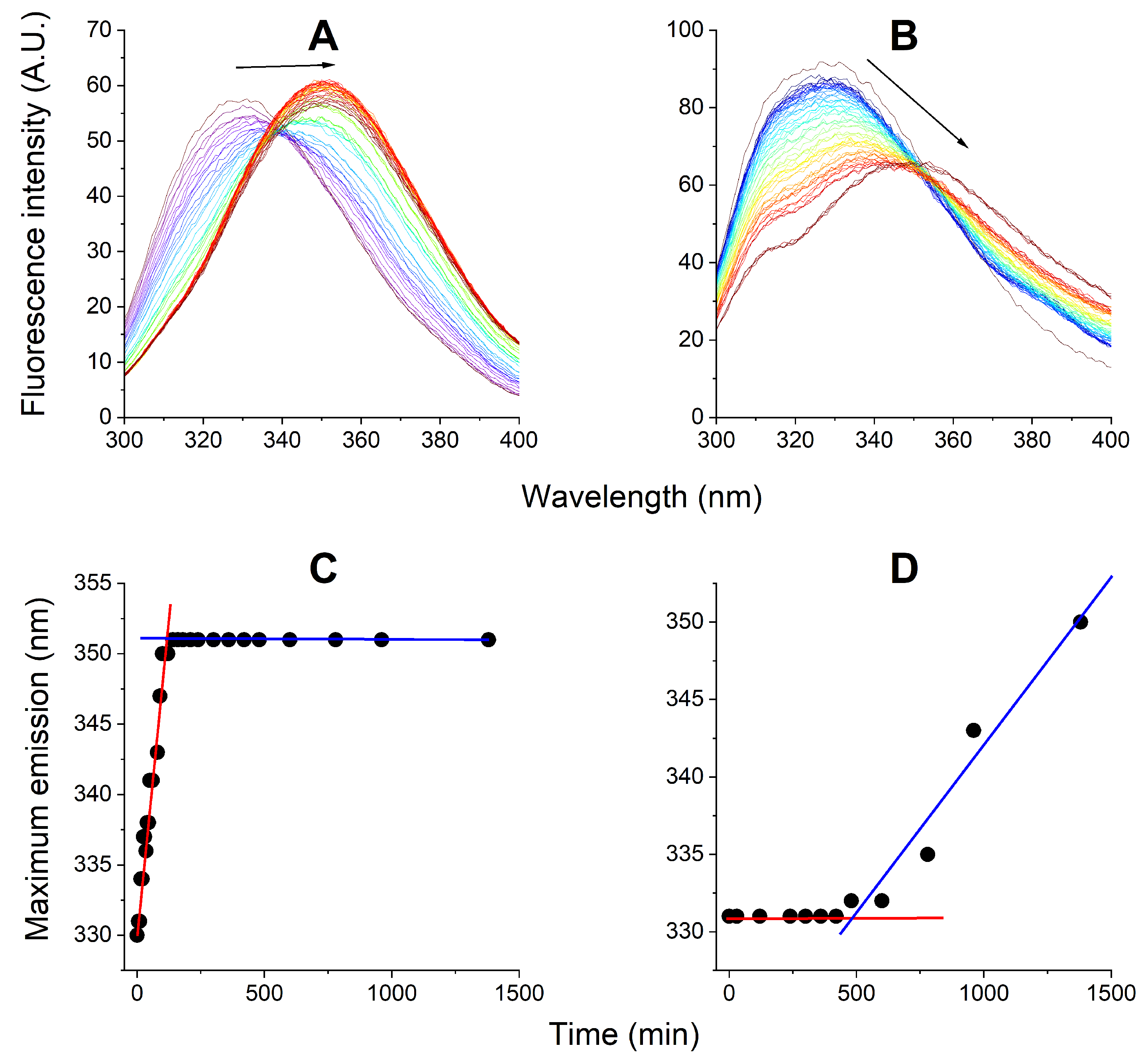

2.2. Interactions of AgNPs with EMAP II and tRNA With and Without TCEP

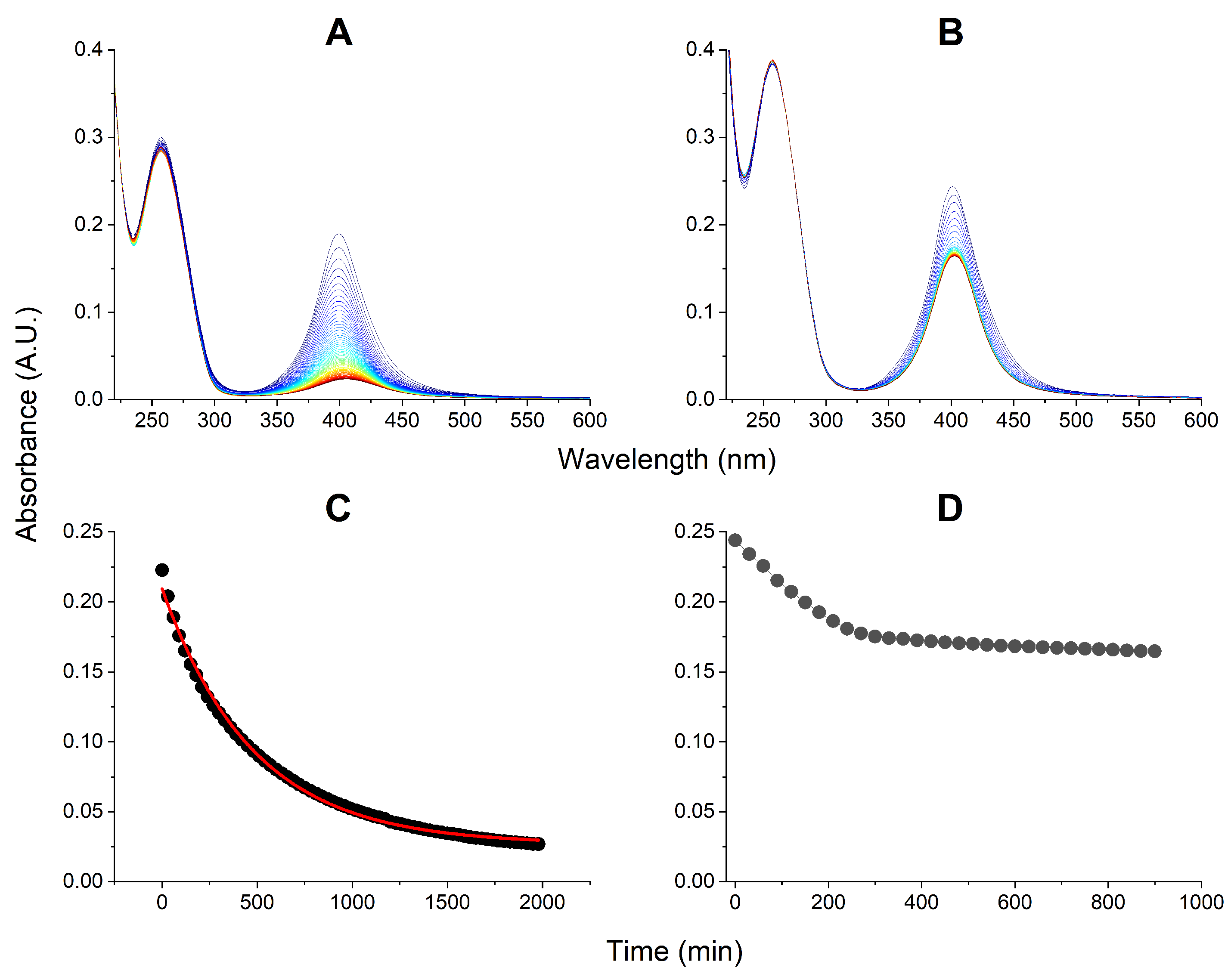

2.3. Interactions of the EMAP II-tRNA Complex with AgNPs

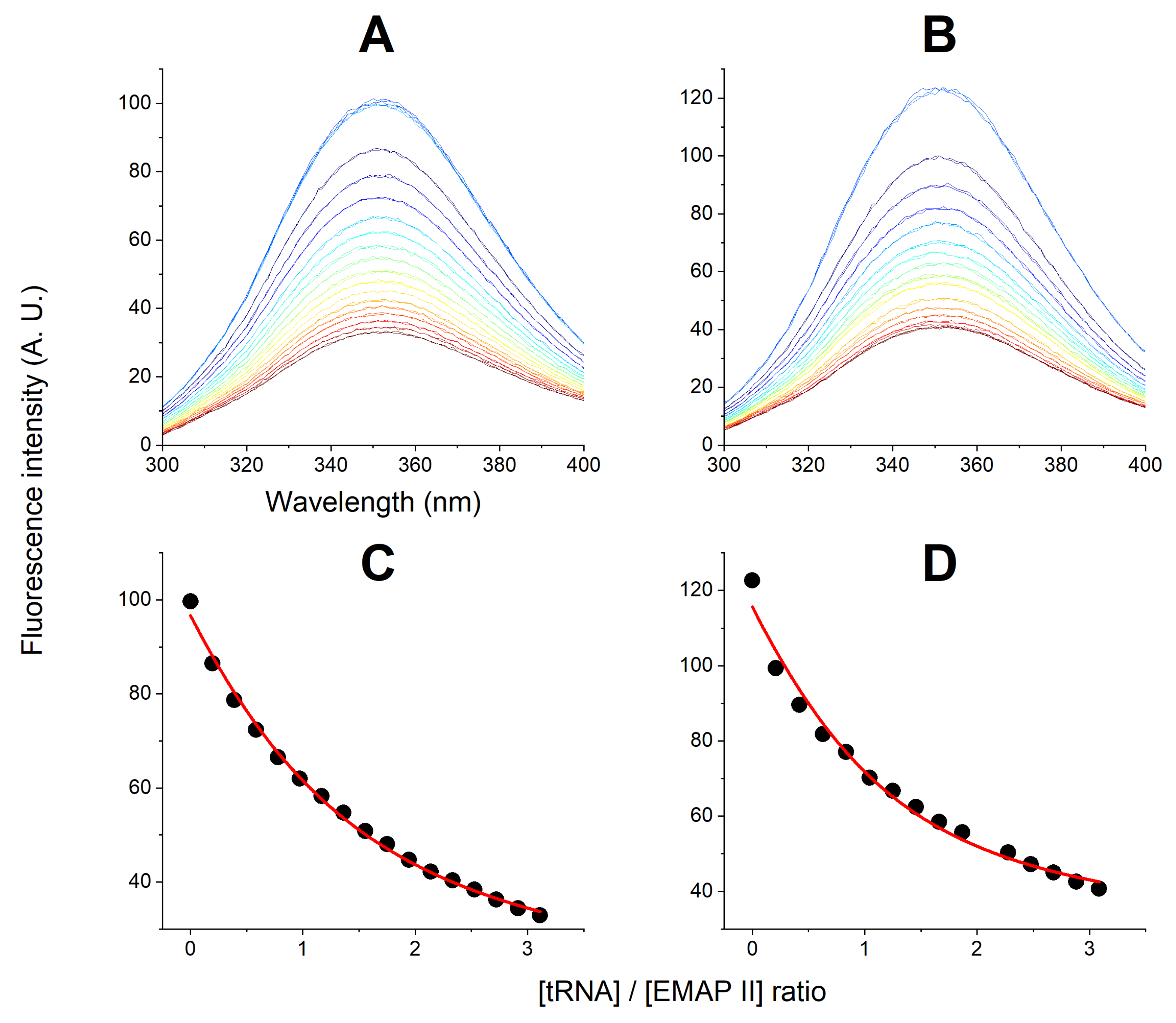

2.4. Determination of the tRNA Binding Affinity to Native and Denatured EMAP II

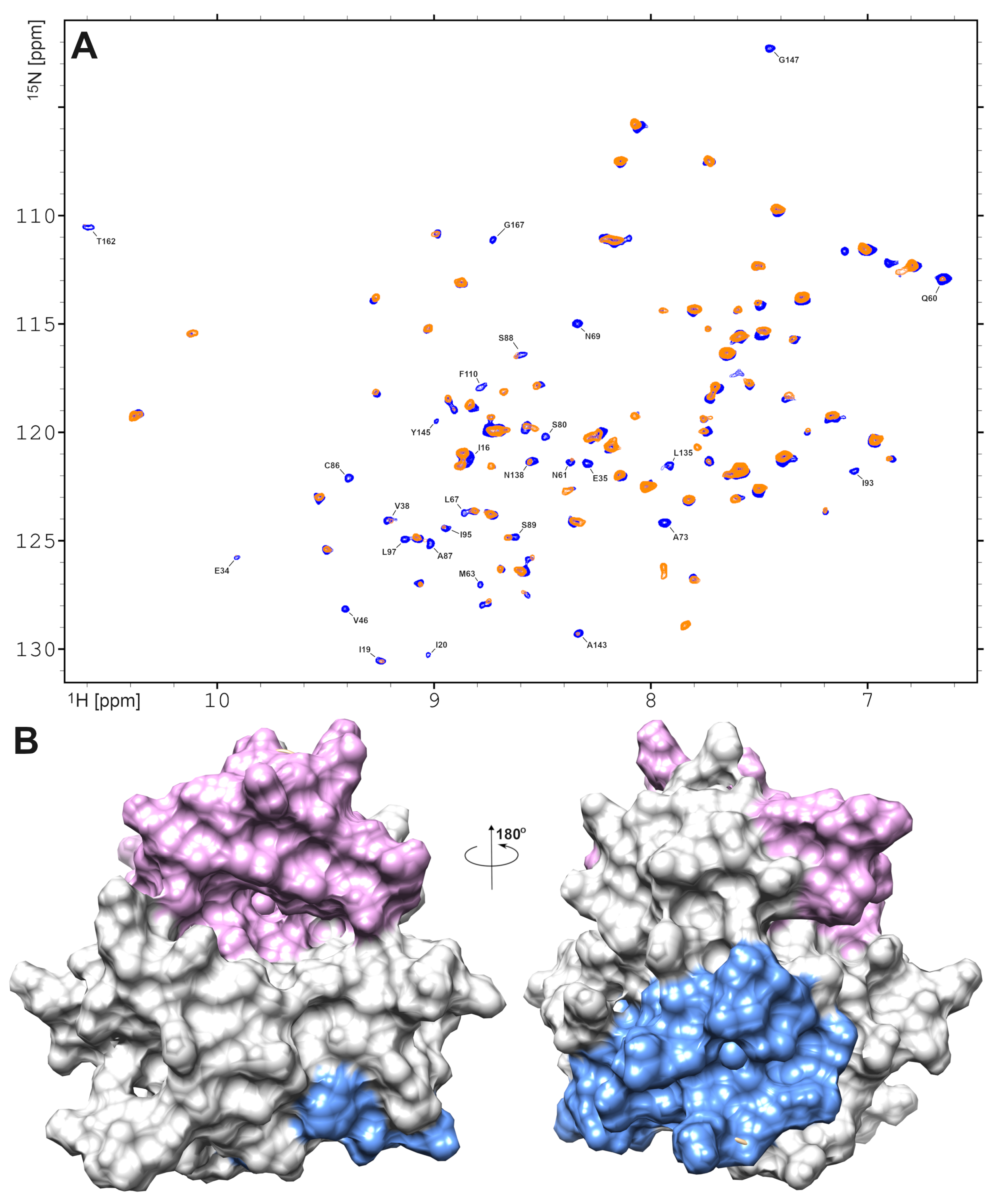

2.5. Structural Information on EMAP II Interaction with AgNPs Provided by NMR Spectroscopy

3. Discussion

3.1. Initial EMAP II Interactions with AgNPs

3.2. Kinetic Experiments: EMAP II Interactions with AgNPs and AgNP Decay

3.3. Kinetic Experiments: EMAP II Denaturation Mechanisms and AgNPs

3.4. Kinetic Experiments: EMAP II Denaturation Mechanisms and tRNA

3.5. The Effect of Ag+ on tRNA Affinity for EMAP II

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. EMAP II Protein Expression and Purification

4.2. 15N-Labeled EMAP II Variant

4.3. Dynamic Light Scattering and Zeta Potential

4.4. Ultraviolet-Visible Spectroscopy

4.5. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

A Note Regarding Temperature Dependence of Buffers and EMAP II pI

4.6. NMR Spectroscopy

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMAP II | Endothelial monocyte-activating polypeptide II |

| AgNPs | Silver Nanoparticles |

| NP | Nanoparticles |

| ARS | Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase |

| MSC | Multi-tRNA synthetase complex |

| AIMP1 | ARS-interacting multifunctional protein 1 |

| TCEP | tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine |

| PDI | Polydispersity Index |

| ESI-MS | Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| tRNA | Transfer RNA |

| pI | isoelectric point |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| HSQC | Heteronuclear Single Quantum Correlation |

| CrAcAc | Chromium(III) acetylacetonate |

References

- Lee, S.W.; Cho, B.H.; Park, S.G.; Kim, S. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complexes: Beyond translation. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 3725–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirande, M. The aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complex. In Macromolecular Protein Complexes: Structure and Function; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Gogonea, V.; Fox, P.L. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases of the multi-tRNA synthetase complex and their role in tumorigenesis. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 19, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Sun, B.; Huang, S.; Yu, D.; Zhang, X. Roles of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase-interacting multi-functional proteins in physiology and cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.; Jung, H.J.; Hong, S.; Cho, Y.; Park, J.; Cho, D.; Kim, T.S. Aminoacyl transfer ribonucleic acid synthetase complex-interacting multifunctional protein 1 induces microglial activation and M1 polarization via the mitogen-activated protein kinase/nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathway. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 977205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, V.; Kalita, P.; Shukla, H.; Kumar, A.; Tripathi, T. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases: Structure, function, and drug discovery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, Y.G.; Park, H.; Kim, T.; Lee, J.W.; Park, S.G.; Seol, W.; Kim, J.E.; Lee, W.H.; Kim, S.H.; Park, J.E.; et al. A cofactor of tRNA synthetase, p43, is secreted to up-regulate proinflammatory genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 23028–23033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, H.; Kim, D.; Park, C.; Huh, Y.; Jung, J.; Chung, H.J.; Jeong, N.Y. Fluorescence-based analysis of noncanonical functions of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase-interacting multifunctional proteins (AIMPs) in peripheral nerves. Materials 2019, 12, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, H.J.; Lim, H.X.; Song, J.H.; Lee, A.; Kim, E.; Cho, D.; Cohen, E.P.; Kim, T.S. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase-interacting multifunctional protein 1 suppresses tumor growth in breast cancer-bearing mice by negatively regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cell functions. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016, 65, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Schimmel, P. Essential nontranslational functions of tRNA synthetases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Tian, L.; You, R.; Halpert, M.M.; Konduri, V.; Baig, Y.C.; Paust, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; Jia, F.; et al. AIMP1 potentiates TH1 polarization and is critical for effective antitumor and antiviral immunity. Front. Immunol. 2018, 8, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.G.; Kang, Y.S.; Ahn, Y.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, K.R.; Kim, K.W.; Koh, G.Y.; Ko, Y.G.; Kim, S. Dose-dependent biphasic activity of tRNA synthetase-associating factor, p43, in angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 45243–45248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Ignatov, M.; Musier-Forsyth, K.; Schimmel, P.; Yang, X.L. Crystal structure of tetrameric form of human lysyl-tRNA synthetase: Implications for multisynthetase complex formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2331–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, J.; Ryan, J.; Brett, G.; Chen, J.; Shen, H.; Fan, Y.; Godman, G.; Familletti, P.; Wang, F.; Pan, Y. Endothelial monocyte-activating polypeptide II. A novel tumor-derived polypeptide that activates host-response mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 20239–20247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, N.; Schwarz, M.A.; Verma, V.; Cappiello, C.; Schwarz, R.E. Endothelial monocyte activating polypeptide II interferes with VEGF-induced proangiogenic signaling. Lab. Investig. 2009, 89, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.D.; Lal, C.V.; Persad, E.A.; Lowe, C.W.; Schwarz, A.M.; Awasthi, N.; Schwarz, R.E.; Schwarz, M.A. Endothelial monocyte-activating polypeptide II mediates macrophage migration in the development of hyperoxia-induced lung disease of prematurity. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016, 55, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Ma, X.; Zhang, H.; Lan, C. Novel preparation of laponite based theranostic silver nanocomposite for drug delivery, radical scavenging and healing efficiency for wound care management after surgery. Regen. Ther. 2025, 28, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z. An antifouling hydrogel containing silver nanoparticles for modulating the therapeutic immune response in chronic wound healing. Langmuir 2018, 35, 1837–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, T.Q.; Thanh, N.T.H.; Thuy, N.T.; Van Chung, P.; Hung, P.N.; Le, A.T.; Hanh, N.T.H. Cytotoxicity and antiviral activity of electrochemical–synthesized silver nanoparticles against poliovirus. J. Virol. Methods 2017, 241, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaswal, T.; Gupta, J. A review on the toxicity of silver nanoparticles on human health. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 81, 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Cheng, F.Y.; Chiu, H.W.; Tsai, J.C.; Fang, C.Y.; Chen, C.W.; Wang, Y.J. Cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, apoptosis and the autophagic effects of silver nanoparticles in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 4706–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, K.; Osawa, M.; Okabe, S. In vitro toxicity of silver nanoparticles at noncytotoxic doses to HepG2 human hepatoma cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 6046–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankveld, D.P.; Oomen, A.G.; Krystek, P.; Neigh, A.; Troost-de Jong, A.; Noorlander, C.; Van Eijkeren, J.; Geertsma, R.; De Jong, W. The kinetics of the tissue distribution of silver nanoparticles of different sizes. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 8350–8361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska-Bouta, B.; Sulkowski, G.; Strużyński, W.; Strużyńska, L. Prolonged exposure to silver nanoparticles results in oxidative stress in cerebral myelin. Neurotox. Res. 2019, 35, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronesi, G.; Aude-Garcia, C.; Kieffer, I.; Gallon, T.; Delangle, P.; Herlin-Boime, N.; Rabilloud, T.; Carrière, M. Exposure-dependent Ag+ release from silver nanoparticles and its complexation in AgS 2 sites in primary murine macrophages. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 7323–7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluska, K.; Peris-Díaz, M.D.; Płonka, D.; Moysa, A.; Dadlez, M.; Deniaud, A.; Bal, W.; Krezel, A. Formation of highly stable multinuclear AgnSn clusters in zinc fingers disrupts their structure and function. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 1329–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluska, K.; Veronesi, G.; Deniaud, A.; Hajdu, B.; Gyurcsik, B.; Bal, W.; Krezel, A. Structures of silver fingers and a pathway to their genotoxicity. Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202116621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerber, O.; Tran, J.; Misiaszek, A.; Chorążewska, A.; Bal, W.; Krezel, A. Zn(II) to Ag(I) swap in Rad50 zinc hook domain leads to interprotein complex disruption through the formation of highly stable Agx(Cys)y cores. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 4076–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, V.T.; Karepina, E.; Chevallet, M.; Gallet, B.; Cottet-Rousselle, C.; Charbonnier, P.; Moriscot, C.; Michaud-Soret, I.; Bal, W.; Fuchs, A.; et al. Nuclear translocation of silver ions and hepatocyte nuclear receptor impairment upon exposure to silver nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 1373–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazowski, A.J.; Stillman, M.J. Silver binding to rabbit liver zinc metallothionein and zinc α and β fragments. Formation of silver metallothionein with silver(I): Protein ratios of 6, 12, and 18 observed using circular dichroism spectroscopy. Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 3363–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Worms, I.A.; Herlin-Boime, N.; Truffier-Boutry, D.; Michaud-Soret, I.; Mintz, E.; Vidaud, C.; Rollin-Genetet, F. Interaction of silver nanoparticles with metallothionein and ceruloplasmin: Impact on metal substitution by Ag(I), corona formation and enzymatic activity. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 6581–6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozhko, D.; Kolomiiets, L.; Zhukova, L.; Taube, M.; Kozak, M.; Dadlez, M.; Kornelyuk, O.; Zhukov, I. Solution 3D structure and conformational flexibility of the endothelial monocyte activating polypeptide II (EMAP II) revealed by NMR spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Struct. Biol. 2025, 218, 108280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, A.; Rodschinka, G.; Nedialkova, D.D. High-resolution quantitative profiling of tRNA abundance and modification status in eukaryotes by mim-tRNAseq. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 1802–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goch, W.; Bal, W. Stochastic or not? method to predict and quantify the stochastic effects on the association reaction equilibria in nanoscopic systems. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Jani, J.; Vijayasurya, n.; Mochi, J.; Tabasum, S.; Sabarwal, A.; Pappachan, A. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase—A molecular multitasker. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e23219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.L. Formation constants for interaction of citrate with calcium and magnesium lons. Anal. Biochem. 1974, 62, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krezel, A.; Latajka, R.; Bujacz, G.D.; Bal, W. Coordination properties of tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine, a newly introduced thiol reductant, and its oxide. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 1994–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, S.B.; Brevard, C.; Pagelot, A.; Sadler, P. Stable, chelated tetrahedral bis (phosphine) silver(I) complexes. A novel application of INEPT to silver-109 {phosphorus-31}NMR. Inorg. Chem. 1985, 24, 4278–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijboom, R.; Bowen, R.J.; Berners-Price, S.J. Coordination complexes of silver(I) with tertiary phosphine and related ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009, 253, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozhko, D.; Stanek, J.; Kazimierczuk, K.; Zawadzka-Kazimierczuk, A.; Kozminski, W.; Zhukov, I.; Kornelyuk, A. 1H, 13C, and 15N chemical shifts assignments for human endothelial monocyte-activating polypeptide EMAP II. Biomol. NMR Assign. 2013, 7, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bal, W.; Schwerdtle, T.; Hartwig, A. Mechanism of nickel assault on the zinc finger of DNA repair protein XPA. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2003, 16, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossak, K.; Goch, W.; Piatek, K.; Fraczyk, T.; Poznanski, J.; Bonna, A.; Keil, C.; Hartwig, A.; Bal, W. Unusual Zn(II) affinities of zinc fingers of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) nuclear protein. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2015, 28, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-López, L.Z.; Espinoza-Gómez, H.; Somanathan, R. Silver nanoparticles: Electron transfer, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress, beneficial and toxicological effects. Mini review. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2019, 39, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, R.A.; Staples, B.R. Tris/Tris· HCl: A standard buffer for use in the physiologic pH range. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 206–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, R.N.; Roy, L.N.; Ashkenazi, S.; Wollen, J.T.; Dunseth, C.D.; Fuge, M.S.; Durden, J.L.; Roy, C.N.; Hughes, H.M.; Morris, B.T.; et al. Buffer standards for pH measurement of N-(2-Hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) for I = 0.16 mol kg−1 from 5 to 55 °C. J. Solut. Chem. 2009, 38, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reijenga, J.C.; Gagliardi, L.G.; Kenndler, E. Temperature dependence of acidity constants, a tool to affect separation selectivity in capillary electrophoresis. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1155, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E.; Hoogland, C.; Gattiker, A.; Duvaud, S.; Wilkins, M.R.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Bigam, C.G.; Yao, J.; Abildgaard, F.; Dyson, H.J.; Oldfield, E.; Markley, J.L.; Sykes, B.D. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift referencing in biomolecular NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 1995, 6, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaglio, F.; Grzesiek, S.; Vuister, G.W.; Zhu, G.; Pfeifer, J.; Bax, A. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 1995, 6, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Tonelli, M.; Markley, J.L. NMRFAM-SPARKY: Enhanced software for biomolecular NMR spectroscopy. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1325–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, R.E.; Schwarz, M.A. In vivo therapy of local tumor progression by targeting vascular endothelium with EMAP-II. J. Surg. Res. 2004, 120, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Liu, L.; Wang, P.; Yao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Y. EMAP-II sensitize U87MG and glioma stem-like cells to temozolomide via induction of autophagy-mediated cell death and G2/M arrest. Cell Cycle 2017, 16, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznikov, A.; Chaykovskaya, L.; Polyakova, L.; Kornelyuk, A.; Grygorenko, V. Cooperative antitumor effect of endothelial-monocyte activating polypeptide II and flutamide on human prostate cancer xenografts. Exp. Oncol. 2011, 33, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Temperature | Tris | HEPES | EMAP II pI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 7.06 |

| 45 | 7.5 | 7.72 | 6.86 |

| 50 | 7.38 | 7.65 | 6.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kolomiiets, L.; Szczerba, P.; Bal, W.; Zhukov, I. Dissolving Silver Nanoparticles Modulate the Endothelial Monocyte-Activating Polypeptide II (EMAP II) by Partially Unfolding the Protein Leading to tRNA Binding Enhancement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 605. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020605

Kolomiiets L, Szczerba P, Bal W, Zhukov I. Dissolving Silver Nanoparticles Modulate the Endothelial Monocyte-Activating Polypeptide II (EMAP II) by Partially Unfolding the Protein Leading to tRNA Binding Enhancement. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):605. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020605

Chicago/Turabian StyleKolomiiets, Lesia, Paulina Szczerba, Wojciech Bal, and Igor Zhukov. 2026. "Dissolving Silver Nanoparticles Modulate the Endothelial Monocyte-Activating Polypeptide II (EMAP II) by Partially Unfolding the Protein Leading to tRNA Binding Enhancement" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 605. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020605

APA StyleKolomiiets, L., Szczerba, P., Bal, W., & Zhukov, I. (2026). Dissolving Silver Nanoparticles Modulate the Endothelial Monocyte-Activating Polypeptide II (EMAP II) by Partially Unfolding the Protein Leading to tRNA Binding Enhancement. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 605. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020605