Cholesterol Metabolism: An Ally in the Development and Progression of Cervical Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Homeostasis of Cholesterol Metabolism

3. Alterations of Cholesterol Metabolism in Cervical Cancer: A Clinical Approach

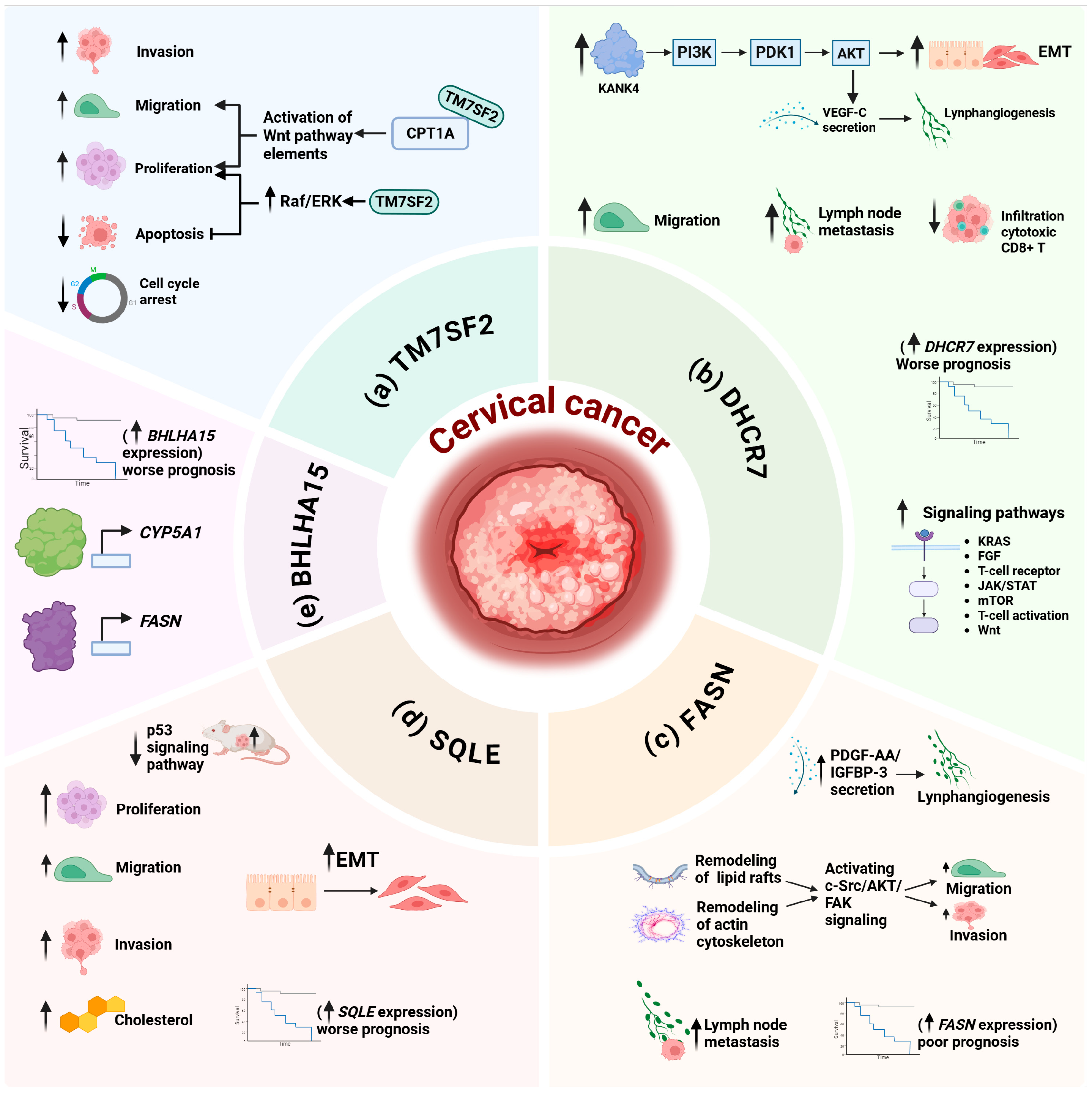

4. Alterations of Cholesterol Metabolism in Cervical Cancer: A Molecular Approach

5. Regulation of Cholesterol Metabolism by HPV Oncoproteins

| Oncoprotein | Model | Biomolecule | Level | Gene or Protein | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E6 | C-33 A cells | mRNA |  | APP, EBP, FDFT1, FDX1, GNB3, LDLR, LIMA1, LRP5, MAPK1, PRKAA1, SCARB1, SOAT1, SOD1, STARD4, TTC39B | [73] |

| CUBN, FGF1, SC5D, TM7SF2, TNFSF4, LRP1, PMP22 | ||||

| U-2 OS cells | mRNA |  | HMGCS1, LBR, PRKAA1 | [77] | |

| FDXR | ||||

| E7 | C-33 A cells | mRNA |  | DHCR24, LIMA1, LDLR, FDFT1, LRP5, DHCR7, SREBF2, SCARB1, LSS, EBP, TTC39B, DGAT2, ABCA2, INSIG1, GNB3 | [73] |

| CUBN, CYP39A1, TNFSF4, FGF1, LEPR, PCTP, SC5D, PMP22 | ||||

| E6/E7 | HaCaT cells | mRNA |  | ABCA5, APLP2, CEBPA, CLN8, CYP7B1, DHCR24, EPHX2, FDFT1, FDXR, HMGCS1, HSD17B7, LBR, LDLRAP1, LMF1, MVD, MVK, NPC2, PCSK9, PCTP, SAA1, SEC14L2, SOAT2, SQLE, SULT2B1, THRB, TM7SF2, TTC39B | [78] |

| ABCA1, ABCA2, ABCG1, ACADL, CUBN, CYB5R3, GNB3, HSD3B7, LEPR, LRP5, NPY1R, PMP22, PMVK, PRKAA2, SCAP, SCARB1, SMPD1, VLDLR | ||||

| HEKn cells | Protein |  | LBR, VDLR | [79] | |

| APLP2, APOE, CLN8, LDLR, LIPE, NPC2, NSDHL, SC5D, SCAP | ||||

| NOKs Cells | mRNAs and their protein products |  | PMVK | [80] | |

| NPC2, SEC14L2, SAA1 |

6. Cholesterol Metabolism as a Therapeutic Opportunity in Cervical Cancer

7. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ikeda, S.; Ueda, Y.; Hara, M.; Yagi, A.; Kitamura, T.; Kitamura, Y.; Konishi, H.; Kakizoe, T.; Sekine, M.; Enomoto, T.; et al. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine to Prevent Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Japan: A Nationwide Case-Control Study. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, C.; Brotherton, J.M.L.; Pillsbury, A.; Jayasinghe, S.; Donovan, B.; Macartney, K.; Marshall, H. The Impact of 10 Years of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination in Australia: What Additional Disease Burden Will a Nonavalent Vaccine Prevent? Eurosurveillance 2018, 23, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Today. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/en (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Singh, G.K.; Azuine, R.E.; Siahpush, M. Global Inequalities in Cervical Cancer Incidence and Mortality Are Linked to Deprivation, Low Socioeconomic Status, and Human Development. Int. J. MCH AIDS 2012, 1, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Martel, C.; Plummer, M.; Vignat, J.; Franceschi, S. Worldwide Burden of Cancer Attributable to HPV by Site, Country and HPV Type. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, S.F.; Park, S.; Schweizer, J.; Berard-Bergery, M.; Pitot, H.C.; Lee, D.; Lambert, P.F. Cervical Cancers Require the Continuous Expression of the Human Papillomavirus Type 16 E7 Oncoprotein Even in the Presence of the Viral E6 Oncoprotein. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 4008–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Q.; Wang, L.; Zuo, L.; Gao, S.; Jiang, X.; Han, Y.; Lin, J.; Peng, M.; Wu, N.; Tang, Y.; et al. HPV E6/E7: Insights into Their Regulatory Role and Mechanism in Signaling Pathways in HPV-Associated Tumor. Cancer Gene Ther. 2024, 31, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Pedraza, Y.; Muñoz-Bello, J.O.; Ramos-Chávez, L.A.; Martínez-Ramírez, I.; Olmedo-Nieva, L.; Manzo-Merino, J.; López-Saavedra, A.; Pérez-de la Cruz, V.; Lizano, M. HPV16 E6 and E7 Oncoproteins Stimulate the Glutamine Pathway Maintaining Cell Proliferation in a SNAT1-Dependent Fashion. Viruses 2023, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.G.; Ramesh Wanjari, U.; Valsala Gopalakrishnan, A.; Jayaraj, R.; Katturajan, R.; Kannampuzha, S.; Murali, R.; Namachivayam, A.; Evan Prince, S.; Vellingiri, B.; et al. HPV-Associated Cancers: Insights into the Mechanistic Scenario and Latest Updates. Med. Oncol. 2023, 40, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Chen, S.; Bai, X.; Liao, M.; Qiu, Y.; Zheng, L.L.; Yu, H. Targeting Cholesterol Metabolism in Cancer: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Implications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 218, 115907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBerardinis, R.J.; Lum, J.J.; Hatzivassiliou, G.; Thompson, C.B. The Biology of Cancer: Metabolic Reprogramming Fuels Cell Growth and Proliferation. Cell Metab. 2008, 7, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe-Seyler, K.; Honegger, A.; Bossler, F.; Sponagel, J.; Bulkescher, J.; Lohrey, C.; Hoppe-Seyler, F. Viral E6/E7 Oncogene and Cellular Hexokinase 2 Expression in HPV-Positive Cancer Cell Lines. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 106342–106351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, M.; Kabekkodu, S.P.; Chakrabarty, S. Exploring the Metabolic Alterations in Cervical Cancer Induced by HPV Oncoproteins: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targets. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Hou, W.J.; Zhao, Y.J.; Liu, S.L.; Qiu, X.S.; Wang, E.H.; Wu, G.P. Overexpression of HPV16 E6/E7 Mediated HIF-1α Upregulation of GLUT1 Expression in Lung Cancer Cells. Tumour Biol. 2016, 37, 4655–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riscal, R.; Skuli, N.; Simon, M.C. Even Cancer Cells Watch Their Cholesterol! Mol. Cell 2019, 76, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Q.; Altomare, D.A.; Skele, K.L.; Poulikakos, P.I.; Kuhajda, F.P.; Di Cristofano, A.; Testa, J.R. Positive Feedback Regulation between AKT Activation and Fatty Acid Synthase Expression in Ovarian Carcinoma Cells. Oncogene 2005, 24, 3574–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonen, E. Cellular Cholesterol Trafficking and Compartmentalization. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegele, R.A. Plasma Lipoproteins: Genetic Influences and Clinical Implications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzu, O.F.; Noory, M.A.; Robertson, G.P. The Role of Cholesterol in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2063–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Yang, H.; Song, B.L. Mechanisms and Regulation of Cholesterol Homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Su, P.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, M.; Chen, B.; Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; et al. SREBP1, Targeted by MiR-18a-5p, Modulates Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Breast Cancer via Forming a Co-Repressor Complex with Snail and HDAC1/2. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, P.; Trufa, D.I.; Hohenberger, K.; Tausche, P.; Trump, S.; Mittler, S.; Geppert, C.I.; Rieker, R.J.; Schieweck, O.; Sirbu, H.; et al. Contribution of Serum Lipids and Cholesterol Cellular Metabolism in Lung Cancer Development and Progression. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Xu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Functional Significance of Cholesterol Metabolism in Cancer: From Threat to Treatment. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1982–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Hu, L. Cholesterol Regulates Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis of Colorectal Cancer by Modulating MiR-33a-PIM3 Pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 511, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Cao, Q. Cholesterol Promotes the Migration and Invasion of Renal Carcinoma Cells by Regulating the KLF5/MiR-27a/FBXW7 Pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 502, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, G.; López-Montero, I.; Monroya, F.; Langevin, D. Shear Rheology of Lipid Monolayers and Insights on Membrane Fluidity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 6008–6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.A.; Halverson-Tamboli, R.A.; Rasenick, M.M. Lipid Raft Microdomains and Neurotransmitter Signalling. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.Y.; Chang, C.C.Y.; Ohgami, N.; Yamauchi, Y. Cholesterol Sensing, Trafficking, and Esterification. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006, 22, 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, V.A.; Busso, D.; Maiz, A.; Arteaga, A.; Nervi, F.; Rigotti, A. Physiological and Pathological Implications of Cholesterol. Front. Biosci. Landmark Ed. 2014, 19, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamsa, D.L.; Wongb, J.S.; Hamiltonb, R.L. SR-BI Is Required for Microvillar Channel Formation and the Localization of HDL Particles to the Surface of Adrenocortical Cells in Vivo. J. Lipid Res. 2002, 43, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijers, M.; Kuivenhoven, J.A.; Van De Sluis, B. The Life Cycle of the Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor: Insights from Cellular and in-Vivo Studies. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2015, 26, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.J.; Abi-Mosleh, L.; Wang, M.L.; Deisenhofer, J.; Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S.; Infante, R.E. Structure of N-Terminal Domain of NPC1 Reveals Distinct Subdomains for Binding and Transfer of Cholesterol. Cell 2009, 137, 1213–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.L.; Motamed, M.; Infante, R.E.; Abi-Mosleh, L.; Kwon, H.J.; Brown, M.S.; Goldstein, J.L. Identification of Surface Residues on Niemann-Pick C2 Essential for Hydrophobic Handoff of Cholesterol to NPC1 in Lysosomes. Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigueza, W.V.; Thuahnai, S.T.; Temel, R.E.; Lund-Katz, S.; Phillips, M.C.; Williams, D.L. Mechanism of Scavenger Receptor Class B Type I-Mediated Selective Uptake of Cholesteryl Esters from High Density Lipoprotein to Adrenal Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 20344–20350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papale, G.A.; Hanson, P.J.; Sahoo, D. Extracellular Disulfide Bonds Support Scavenger Receptor Class B Type I-Mediated Cholesterol Transport. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 6245–6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Chen, M.; Song, Z.; Daugherty, A.; Li, X.A. C323 of SR-BI Is Required for SR-BI-Mediated HDL Binding and Cholesteryl Ester Uptake. J. Lipid Res. 2011, 52, 2272–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, H.R.; Sahoo, D. SR-B1’s Next Top Model: Structural Perspectives on the Functions of the HDL Receptor. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2022, 24, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, A.; Goldstein, J.L.; McDonald, J.G.; Brown, M.S. Switch-like Control of SREBP-2 Transport Triggered by Small Changes in ER Cholesterol: A Delicate Balance. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widenmaier, S.B.; Snyder, N.A.; Nguyen, T.B.; Arduini, A.; Lee, G.Y.; Arruda, A.P.; Saksi, J.; Bartelt, A.; Hotamisligil, G.S. NRF1 Is an ER Membrane Sensor That Is Central to Cholesterol Homeostasis. Cell 2017, 171, 1094.e15–1109.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswaran, A.; Laffitte, B.A.; Joseph, S.B.; Mak, P.A.; Wilpitz, D.C.; Edwards, P.A.; Tontonoz, P. Control of Cellular Cholesterol Efflux by the Nuclear Oxysterol Receptor LXR Alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 12097–12102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.S.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Goldstein, J.L. Retrospective on Cholesterol Homeostasis: The Central Role of Scap. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2018, 87, 783–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Tontonoz, P. Liver X Receptors in Lipid Signalling and Membrane Homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Park, M.J.; Ye, S.K.; Kim, C.W.; Kim, Y.N. Elevated Levels of Cholesterol-Rich Lipid Rafts in Cancer Cells Are Correlated with Apoptosis Sensitivity Induced by Cholesterol-Depleting Agents. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 168, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzu, O.F.; Gowda, R.; Noory, M.A.; Robertson, G.P. Modulating Cancer Cell Survival by Targeting Intracellular Cholesterol Transport. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorin, A.; Gabitova, L.; Astsaturov, I. Regulation of Cholesterol Biosynthesis and Cancer Signaling. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2012, 12, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Song, B.-L.; Xu, C. Cholesterol Metabolism in Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.A.; de Souza, S.B.; da Silva Teixeira, L.R.; Okorokov, L.A.; Arnholdt, A.C.V.; Okorokova-Façanha, A.L.; Façanha, A.R. Tumor Cell Cholesterol Depletion and V-ATPase Inhibition as an Inhibitory Mechanism to Prevent Cell Migration and Invasiveness in Melanoma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2018, 1862, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Yang, E.J.; Head, S.A.; Ai, N.; Zhang, B.; Wu, C.; Li, R.J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Dang, Y.; et al. Pharmacological Blockade of Cholesterol Trafficking by Cepharanthine in Endothelial Cells Suppresses Angiogenesis and Tumor Growth. Cancer Lett. 2017, 409, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.A.; Xiong, X.; Zaytseva, Y.Y.; Napier, D.L.; Vallee, E.; Li, A.T.; Wang, C.; Weiss, H.L.; Evers, B.M.; Gao, T. Downregulation of SREBP Inhibits Tumor Growth and Initiation by Altering Cellular Metabolism in Colon Cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Zhang, L.; Gong, S.; Yang, X.; Xu, G. Cholesterol Metabolism and Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms, Immune Regulation and an Epidemiological Perspective (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 56, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Lv, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhan, Q. Dysregulation of Cholesterol Metabolism in Cancer Progression. Oncogene 2023, 42, 3289–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, G.F.; Niyonzima, N.; Atwine, R.; Tusubira, D.; Mugyenyi, G.R.; Ssedyabane, F. Dyslipidemia: Prevalence and Association with Precancerous and Cancerous Lesions of the Cervix; a Pilot Study. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Zheng, R.; Yu, C.; Su, Y.; Yan, X.; Qu, F. Predictive Role of Serum Cholesterol and Triglycerides in Cervical Cancer Survival. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Wang, L.; Jin, M.; Shou, Y.; Zhu, H.; Li, A. The Clinical Value of Lipid Abnormalities in Early Stage Cervical Cancer. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 3903–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Q.; Song, J.R.; Zheng, X.Q.; Zheng, H.; Yi, H. The Impact of Diabetes, Hypercholesterolemia, and Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) on the Survival of Cervical Cancer Patients. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Li, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Yao, Q. Correlation Study of Serum Lipid Levels and Lipid Metabolism-Related Genes in Cervical Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1384778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Meng, H.; Jin, Y.; Shi, X.; Wu, Y.; Fan, D.; Wang, X.; Jia, X.; Dai, H. Serum Lipid Profile in Gynecologic Tumors: A Retrospective Clinical Study of 1,550 Patients. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2016, 37, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennati, A.M.; Castelli, M.; Della Fazia, M.A.; Beccari, T.; Caruso, D.; Servillo, G.; Roberti, R. Sterol Dependent Regulation of Human TM7SF2 Gene Expression: Role of the Encoded 3beta-Hydroxysterol Delta14-Reductase in Human Cholesterol Biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1761, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Pan, S.; Wang, Z.-W.; Zhu, X. TM7SF2 Regulates Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis by Activation of C-Raf/ERK Pathway in Cervical Cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.; Pan, S.; Zhou, Q.; Ji, H.; Zhu, X. TM7SF2-Induced Lipid Reprogramming Promotes Cell Proliferation and Migration via CPT1A/Wnt/β-Catenin Axis in Cervical Cancer Cells. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Cerro, L.S.; Porter, F.D. 3beta-Hydroxysterol Delta7-Reductase and the Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005, 84, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Liu, S.; Long, J.; Yan, B. High DHCR7 Expression Predicts Poor Prognosis for Cervical Cancer. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 8383885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Xiong, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, A.; Zhu, D.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H. DHCR7 Promotes Lymph Node Metastasis in Cervical Cancer through Cholesterol Reprogramming-Mediated Activation of the KANK4/PI3K/AKT Axis and VEGF-C Secretion. Cancer Lett. 2024, 584, 216609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, R.G.; Zasłona, Z.; Galván-Peña, S.; Koppe, E.L.; Sévin, D.C.; Angiari, S.; Triantafilou, M.; Triantafilou, K.; Modis, L.K.; O’Neill, L.A. An Unexpected Link between Fatty Acid Synthase and Cholesterol Synthesis in Proinflammatory Macrophage Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 5509–5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Q.; Liu, P.; Zhang, C.; Liu, T.; Wang, W.; Shang, C.; Wu, J.; Liao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; et al. FASN Promotes Lymph Node Metastasis in Cervical Cancer via Cholesterol Reprogramming and Lymphangiogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; He, Z.; Du, L. Targeting Squalene Epoxidase in the Treatment of Metabolic-Related Diseases: Current Research and Future Directions. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Qiao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zheng, L. Squalene Epoxidase Facilitates Cervical Cancer Progression by Modulating Tumor Protein P53 Signaling Pathway. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.C.; Li, Y.F.; Qiu, L.; Jin, S.Z.; Shen, Y.N.; Zhang, C.H.; Cui, J.; Wang, T.J. SQLE-a Promising Prognostic Biomarker in Cervical Cancer: Implications for Tumor Malignant Behavior, Cholesterol Synthesis, Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition, and Immune Infiltration. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H. Expression Analysis of MIST1 and EMT Markers in Primary Tumor Samples Points to MIST1 as a Biomarker of Cervical Cancer. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Li, S.; Bai, J.; Wan, F.-z.; Wang, H.; Hu, X.-y.; Chen, L.; Zeng, S.-h.; Qin, X.-l.; Zou, X.-x.; et al. BHLHA15 Promotes Cervical Cancer Cholesterol Synthesis and Tumor Progression. Cell. Signal. 2025, 134, 111966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xu, T. Effect of HPV Oncoprotein on Carbohydrate and Lipid Metabolism in Tumor Cells. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2024, 24, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AmiGO 2: Term Details for “Cholesterol Metabolic Process” (GO:0008203). Available online: https://amigo.geneontology.org/amigo/term/GO:0008203 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Olmedo-Nieva, L.; Muñoz-Bello, J.O.; Martínez-Ramírez, I.; Martínez-Gutiérrez, A.D.; Ortiz-Pedraza, Y.; González-Espinosa, C.; Madrid-Marina, V.; Torres-Poveda, K.; Bahena-Roman, M.; Lizano, M. RIPOR2 Expression Decreased by HPV-16 E6 and E7 Oncoproteins: An Opportunity in the Search for Prognostic Biomarkers in Cervical Cancer. Cells 2022, 11, 3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.T.; Lee, C.H. Roles of Farnesyl-Diphosphate Farnesyltransferase 1 in Tumour and Tumour Microenvironments. Cells 2020, 9, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, F.P.; Alborzinia, H.; dos Santos, A.F.; Nepachalovich, P.; Pedrera, L.; Zilka, O.; Inague, A.; Klein, C.; Aroua, N.; Kaushal, K.; et al. 7-Dehydrocholesterol Is an Endogenous Suppressor of Ferroptosis. Nature 2024, 626, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershov, P.; Kaluzhskiy, L.; Mezentsev, Y.; Yablokov, E.; Gnedenko, O.; Ivanov, A. Enzymes in the Cholesterol Synthesis Pathway: Interactomics in the Cancer Context. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paget-Bailly, P.; Meznad, K.; Bruyère, D.; Perrard, J.; Herfs, M.; Jung, A.C.; Mougin, C.; Prétet, J.L.; Baguet, A. Comparative RNA Sequencing Reveals That HPV16 E6 Abrogates the Effect of E6*I on ROS Metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, R.; Tao, R.; Li, X.; Shang, T.; Zhao, S.; Ren, Q. Expression Profiling of MRNA and Functional Network Analyses of Genes Regulated by Human Papilloma Virus E6 and E7 Proteins in HaCaT Cells. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 979087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dust, K.; Carpenter, M.; Chen, J.C.Y.; Grant, C.; McCorrister, S.; Westmacott, G.R.; Severini, A. Human Papillomavirus 16 E6 and E7 Oncoproteins Alter the Abundance of Proteins Associated with DNA Damage Response, Immune Signaling and Epidermal Differentiation. Viruses 2022, 14, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Klimentová, J.; Göckel-Krzikalla, E.; Ly, R.; Gmelin, N.; Hotz-Wagenblatt, A.; Řehulková, H.; Stulík, J.; Rösl, F.; Niebler, M. Combined Transcriptome and Proteome Analysis of Immortalized Human Keratinocytes Expressing Human Papillomavirus 16 (HPV16) Oncogenes Reveals Novel Key Factors and Networks in HPV-Induced Carcinogenesis. mSphere 2019, 4, e00129-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, P.L.; Zhao, C.; Turner, E.; Schlieker, C. The Lamin B Receptor Is Essential for Cholesterol Synthesis and Perturbed by Disease-Causing Mutations. eLife 2016, 5, e16011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Kang, C. Living Beyond Restriction: LBR Promotes Cellular Immortalization by Suppressing Genomic Instability and Senescence. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 2091–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzina, Z.; Solanko, L.M.; Mehadi, A.S.; Jensen, M.L.V.; Lund, F.W.; Modzel, M.; Szomek, M.; Solanko, K.A.; Dupont, A.; Nielsen, G.K.; et al. Niemann-Pick C2 Protein Regulates Sterol Transport between Plasma Membrane and Late Endosomes in Human Fibroblasts. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2018, 213, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.M.; Ning, Z.L.; Ma, C.; Liu, T.B.; Tao, B.; Guo, L. Low Expression of Lysosome-Related Genes KCNE1, NPC2, and SFTPD Promote Cancer Cell Proliferation and Tumor Associated M2 Macrophage Polarization in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, G.; Zeng, G.; Wei, D. The Role of NPC2 Gene in Glioma Was Investigated Based on Bioinformatics Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, E.J.; Zelenko, Z.; Neel, B.A.; Antoniou, I.M.; Rajan, L.; Kase, N.; LeRoith, D. Elevated Tumor LDLR Expression Accelerates LDL Cholesterol-Mediated Breast Cancer Growth in Mouse Models of Hyperlipidemia. Oncogene 2017, 36, 6462–6471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Bao, L.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Yi, L.; Lei, W.; Yang, Z.; Lu, Y.; You, B.; You, Y.; et al. SCARB1 in Extracellular Vesicles Promotes NPC Metastasis by Co-Regulating M1 and M2 Macrophage Function. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moestrup, S.K.; Kozyraki, R. Cubilin, a High-Density Lipoprotein Receptor. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2000, 11, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyraki, R.; Verroust, P.; Cases, O. Cubilin, the Intrinsic Factor-Vitamin B12 Receptor. Vitam. Horm. 2022, 119, 65–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, Y. Bioinformatics for The Prognostic Value and Function of Cubilin (CUBN) in Colorectal Cancer. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e922447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, C.E.; Lu, D.; Witters, L.A.; Newgard, C.B.; Birnbaum, M.J. The Role of AMPK and MTOR in Nutrient Sensing in Pancreatic Beta-Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 10341–10351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S. PRKAA1 Promotes Proliferation and Inhibits Apoptosis of Gastric Cancer Cells Through Activating JNK1 and Akt Pathways. Oncol. Res. 2020, 28, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; Yang, S.; Yu, Q.; Xu, S. PRKAA1 Predicts Prognosis and Is Associated with Immune Characteristics in Gastric Cancer. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, F. Regulation of SREBP-Mediated Gene Expression. Sheng Wu Wu Li Hsueh Bao 2012, 28, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakan, I.; Laplante, M. Connecting MTORC1 Signaling to SREBP-1 Activation. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2012, 23, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangle, J.M.; Münger, K. The Human Papillomavirus Type 16 E6 Oncoprotein Activates MTORC1 Signaling and Increases Protein Synthesis. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 9398–9407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Ling, M.T.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, K.N. The Role of the PI3K/Akt/MTOR Signalling Pathway in Human Cancers Induced by Infection with Human Papillomaviruses. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurya, S.K.; Chaudhri, S.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, S. Repurposing of Metabolic Drugs Metformin and Simvastatin as an Emerging Class of Cancer Therapeutics. Pharm. Res. 2025, 42, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V.; Mailankody, S. Research and Development Spending to Bring a Single Cancer Drug to Market and Revenues After Approval. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 1569–1575, Erratum in JAMA Intern Med. 2018, 178, 1433. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirtori, C.R. The Pharmacology of Statins. Pharmacol. Res. 2014, 88, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.J.; Alsehli, A.M.; Gartner, S.N.; Clemensson, L.E.; Liao, S.; Eriksson, A.; Isgrove, K.; Thelander, L.; Khan, Z.; Itskov, P.M.; et al. The Statin Target Hmgcr Regulates Energy Metabolism and Food Intake through Central Mechanisms. Cells 2022, 11, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, S.O.; Budoff, M. Effect of Statins on Atherosclerotic Plaque. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 29, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S. A Century of Cholesterol and Coronaries: From Plaques to Genes to Statins. Cell 2015, 161, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, S.; Crown, J.; Duffy, M.J. Statins Inhibit Proliferation and Induce Apoptosis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Med. Oncol. 2022, 39, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, D.; Undela, K.; D’Cruz, S.; Schifano, F. Statin Use and Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Han, L.; Zheng, A. Association between Statin Use and the Risk, Prognosis of Gynecologic Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 268, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Xu, J.; Ma, L. Simvastatin Enhances Chemotherapy in Cervical Cancer via Inhibition of Multiple Prenylation-Dependent GTPases-Regulated Pathways. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 34, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Climent, E.; Benaiges, D.; Pedro-Botet, J. Hydrophilic or Lipophilic Statins? Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 687585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Yoo, N.J.; Lee, S.H.; Moon, Y.J.; Yun, T.; Kim, H.T.; Lee, J.S. A Randomized Phase II Study of Gefitinib plus Simvastatin versus Gefitinib Alone in Previously Treated Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Home | ClinicalTrials.Gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Lavie, O.; Pinchev, M.; Rennert, H.S.; Segev, Y.; Rennert, G. The Effect of Statins on Risk and Survival of Gynecological Malignancies. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 130, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habis, M.; Wroblewski, K.; Bradaric, M.; Ismail, N.; Yamada, S.D.; Litchfield, L.; Lengyel, E.; Romero, I.L. Statin Therapy Is Associated with Improved Survival in Patients with Non-Serous-Papillary Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, A.; Li, T.; Qin, X.; Li, S. Effect of Statin on Risk of Gynecologic Cancers: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies and Randomized Controlled Trials. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 133, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.K.; Shin, B.S.; Ha, C.S.; Park, W.Y. Would Lipophilic Statin Therapy as a Prognostic Factor Improve Survival in Patients With Uterine Cervical Cancer? Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.F.; Li, H.; Zeng, L.; Yang, H.; Hu, Y.; Qu, Y.; Chen, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, X.; et al. Use of Statins and Risks of Ovarian, Uterine, and Cervical Diseases: A Cohort Study in the UK Biobank. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 80, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Ahn, H.S.; Kim, H.J. Statin Use and Incidence and Mortality of Breast and Gynecology Cancer: A Cohort Study Using the National Health Insurance Claims Database. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 150, 1156–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.W. Statins in Therapy: Understanding Their Hydrophilicity, Lipophilicity, Binding to 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase, Ability to Cross the Blood Brain Barrier and Metabolic Stability Based on Electrostatic Molecular Orbital Studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 85, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Chen, T.; Dong, L.; Li, T.; Xue, H.; Gao, B.; Ding, X.; Wang, H.; Li, H. Fatty Acid Synthase Promotes Breast Cancer Metastasis by Mediating Changes in Fatty Acid Metabolism. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Biswas, M.; Sadhukhan, S.; Sonawane, A. Role of EGFR and FASN in Breast Cancer Progression. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 17, 1249–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giró-Perafita, A.; Palomeras, S.; Lum, D.H.; Blancafort, A.; Viñas, G.; Oliveras, G.; Pérez-Bueno, F.; Sarrats, A.; Welm, A.L.; Puig, T. Preclinical Evaluation of Fatty Acid Synthase and EGFR Inhibition in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4687–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menendez, J.A.; Papadimitropoulou, A.; Steen, T.V.; Cuyàs, E.; Oza-Gajera, B.P.; Verdura, S.; Espinoza, I.; Vellon, L.; Mehmi, I.; Lupu, R. Fatty Acid Synthase Confers Tamoxifen Resistance to ER+/HER2+ Breast Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, D.; Yu, D.; Tian, X.; Liu, J.; Jiang, X.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. Expressions of Fatty Acid Synthase and HER2 Are Correlated with Poor Prognosis of Ovarian Cancer. Med. Oncol. 2015, 32, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaevangelou, E.; Almeida, G.S.; Box, C.; deSouza, N.M.; Chung, Y.L. The Effect of FASN Inhibition on the Growth and Metabolism of a Cisplatin-Resistant Ovarian Carcinoma Model. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, J.; Mariot, C.; Vianna, D.R.B.; Kliemann, L.M.; Chaves, P.S.; Loda, M.; Buffon, A.; Beck, R.C.R.; Pilger, D.A. Fatty Acid Synthase as a Potential New Therapeutic Target for Cervical Cancer. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2022, 94, e20210670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, S.; Guo, Q.; Chen, X.; Luo, X.; Long, Y.; Chong, T.; Ye, M.; He, H.; Lu, A.; Ao, K.; et al. The Inhibition of YTHDF3/M6A/LRP6 Reprograms Fatty Acid Metabolism and Suppresses Lymph Node Metastasis in Cervical Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 916–936, Erratum in Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 3825–3826. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.115928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupu, R.; Menendez, J. Pharmacological Inhibitors of Fatty Acid Synthase (FASN)--Catalyzed Endogenous Fatty Acid Biogenesis: A New Family of Anti-Cancer Agents? Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2006, 7, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.W.; Chang, Y.F.; Chuang, H.Y.; Tai, W.T.; Hwang, J.J. Targeted Therapy with Fatty Acid Synthase Inhibitors in a Human Prostate Carcinoma LNCaP/Tk-Luc-Bearing Animal Model. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012, 15, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fhu, C.W.; Ali, A. Fatty Acid Synthase: An Emerging Target in Cancer. Molecules 2020, 25, 3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchook, G.; Infante, J.; Arkenau, H.T.; Patel, M.R.; Dean, E.; Borazanci, E.; Brenner, A.; Cook, N.; Lopez, J.; Pant, S.; et al. First-in-Human Study of the Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of First-in-Class Fatty Acid Synthase Inhibitor TVB-2640 Alone and with a Taxane in Advanced Tumors. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 34, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, W.; Duque, A.E.D.; Michalek, J.; Konkel, B.; Caflisch, L.; Chen, Y.; Pathuri, S.C.; Madhusudanannair-Kunnuparampil, V.; Floyd, J.; Brenner, A. Phase II Investigation of TVB-2640 (Denifanstat) with Bevacizumab in Patients with First Relapse High-Grade Astrocytoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 2419–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Du, Q.; Mai, Q.; Zou, Q.; Wang, S.; Lin, X.; Chen, Q.; Wei, M.; Chi, C.; Peng, Z.; et al. Targeting FASN Enhances Cisplatin Sensitivity via SLC7A11-Mediated Ferroptosis in Cervical Cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2025, 56, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kridel, S.J.; Axelrod, F.; Rozenkrantz, N.; Smith, J.W. Orlistat Is a Novel Inhibitor of Fatty Acid Synthase with Antitumor Activity. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 2070–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, A.M.; Yanovski, J.A.; Calis, K.A. Orlistat, a New Lipase Inhibitor for the Management of Obesity. Pharmacotherapy 2000, 20, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czumaj, A.; Zabielska, J.; Pakiet, A.; Mika, A.; Rostkowska, O.; Makarewicz, W.; Kobiela, J.; Sledzinski, T.; Stelmanska, E. In Vivo Effectiveness of Orlistat in the Suppression of Human Colorectal Cancer Cell Proliferation. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 3815–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, B.J.; Chen, L.Y.; Hsu, P.H.; Sung, P.H.; Hung, Y.C.; Lee, H.Z. Orlistat Displays Antitumor Activity and Enhances the Efficacy of Paclitaxel in Human Hepatoma Hep3B Cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schcolnik-Cabrera, A.; Chávez-Blanco, A.; Domínguez-Gómez, G.; Taja-Chayeb, L.; Morales-Barcenas, R.; Trejo-Becerril, C.; Perez-Cardenas, E.; Gonzalez-Fierro, A.; Dueñas-González, A. Orlistat as a FASN Inhibitor and Multitargeted Agent for Cancer Therapy. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2018, 27, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Wang, Q.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X. Orlistat Induces Apoptosis and Protective Autophagy in Ovarian Cancer Cells: Involvement of Akt-MTOR-Mediated Signaling Pathway. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 298, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, M.; Almeida, L.Y.; Bastos, D.C.; Ortega, R.M.; Moreira, F.S.; Seguin, F.; Zecchin, K.G.; Raposo, H.F.; Oliveira, H.C.F.; Amoêdo, N.D.; et al. The Fatty Acid Synthase Inhibitor Orlistat Reduces the Growth and Metastasis of Orthotopic Tongue Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gade, M.M.; Hurkadale, P.J. Formulation and Evaluation of Self-Emulsifying Orlistat Tablet to Enhance Drug Release and in Vivo Performance: Factorial Design Approach. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2016, 6, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bebawy, G.; Collier, P.; Williams, P.M.; Burley, J.C.; Needham, D. LDLR-Targeted Orlistat Therapeutic Nanoparticles: Peptide Selection, Assembly, Characterization, and Cell-Uptake in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 676, 125574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osmak, M. Statins and Cancer: Current and Future Prospects. Cancer Lett. 2012, 324, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. The Role of Statins in the Regulation of Breast and Colorectal Cancer and Future Directions. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1578345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansal, V.; Burnham, A.J.; Kinney, B.L.C.; Saba, N.; Paulos, C.; Lesinski, G.B.; Buchwald, Z.S.; Schmitt, N.C. Statin Drugs Enhance Responses to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Head and Neck Cancer Models. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e005940, Erratum in J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e005940corr1. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2022-005940corr1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulian, E.D.; Siregar, N.C. Bajuadji Combination of Simvastatin and FAC Improves Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 53, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Niu, Z.; Zong, Y.; Wang, M.; Yao, L.; Lu, Z.; Liao, Q.; Zhao, Y. Atorvastatin (Lipitor) Attenuates the Effects of Aspirin on Pancreatic Cancerogenesis and the Chemotherapeutic Efficacy of Gemcitabine on Pancreatic Cancer by Promoting M2 Polarized Tumor Associated Macrophages. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 35, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ramírez, I.; Carrillo-García, A.; Contreras-Paredes, A.; Ortiz-Sánchez, E.; Cruz-Gregorio, A.; Lizano, M. Regulation of Cellular Metabolism by High-Risk Human Papillomaviruses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arizmendi-Izazaga, A.; Navarro-Tito, N.; Jiménez-Wences, H.; Mendoza-Catalán, M.A.; Martínez-Carrillo, D.N.; Zacapala-Gómez, A.E.; Olea-Flores, M.; Dircio-Maldonado, R.; Torres-Rojas, F.I.; Soto-Flores, D.G.; et al. Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer: Role of HPV 16 Variants. Pathogens 2021, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, F.J.; Inkman, M.; Rashmi, R.; Muhammad, N.; Gabriel, N.; Miller, C.A.; McLellan, M.D.; Goldstein, M.; Markovina, S.; Grigsby, P.W.; et al. HPV Transcript Expression Affects Cervical Cancer Response to Chemoradiation. J. Clin. Investig. Insight 2021, 6, e138734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dürst, M.; Hoyer, H.; Altgassen, C.; Greinke, C.; Häfner, N.; Fishta, A.; Gajda, M.; Mahnert, U.; Hillemanns, P.; Dimpfl, T.; et al. Prognostic Value of HPV-MRNA in Sentinel Lymph Nodes of Cervical Cancer Patients with PN0-Status. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 23015–23025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Martínez-Ramírez, I.; Muñoz-Bello, J.O.; Contreras-Paredes, A.; Parra-Hernández, E.; Carrillo-García, A.; Lizano, M. Cholesterol Metabolism: An Ally in the Development and Progression of Cervical Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020591

Martínez-Ramírez I, Muñoz-Bello JO, Contreras-Paredes A, Parra-Hernández E, Carrillo-García A, Lizano M. Cholesterol Metabolism: An Ally in the Development and Progression of Cervical Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020591

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Ramírez, Imelda, J. Omar Muñoz-Bello, Adriana Contreras-Paredes, Elías Parra-Hernández, Adela Carrillo-García, and Marcela Lizano. 2026. "Cholesterol Metabolism: An Ally in the Development and Progression of Cervical Cancer" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020591

APA StyleMartínez-Ramírez, I., Muñoz-Bello, J. O., Contreras-Paredes, A., Parra-Hernández, E., Carrillo-García, A., & Lizano, M. (2026). Cholesterol Metabolism: An Ally in the Development and Progression of Cervical Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020591