Chimeric Approach to Identify Molecular Determinants of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors

Abstract

1. Introduction

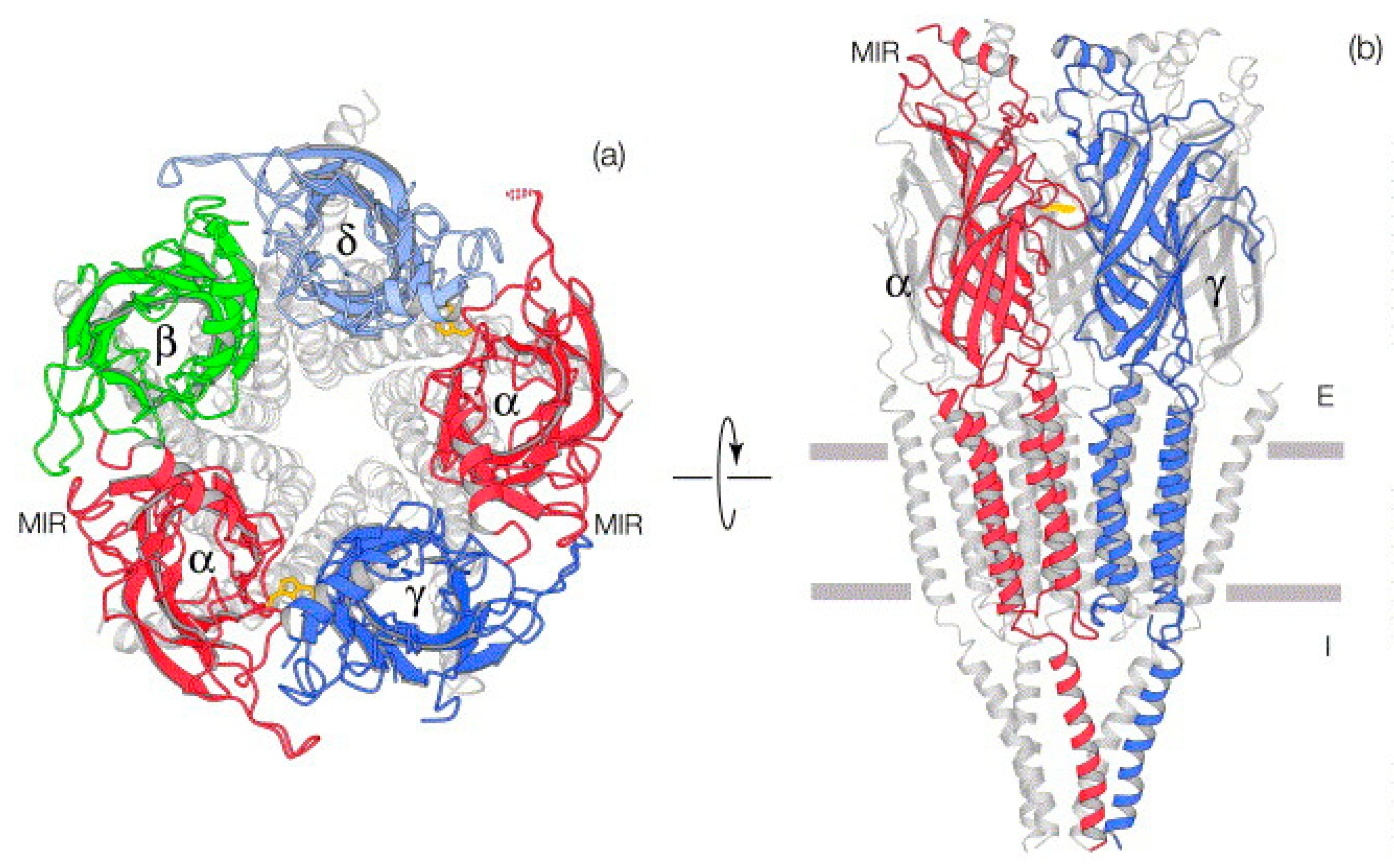

2. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors (nAChRs)

3. Structural Homologs of nAChRs

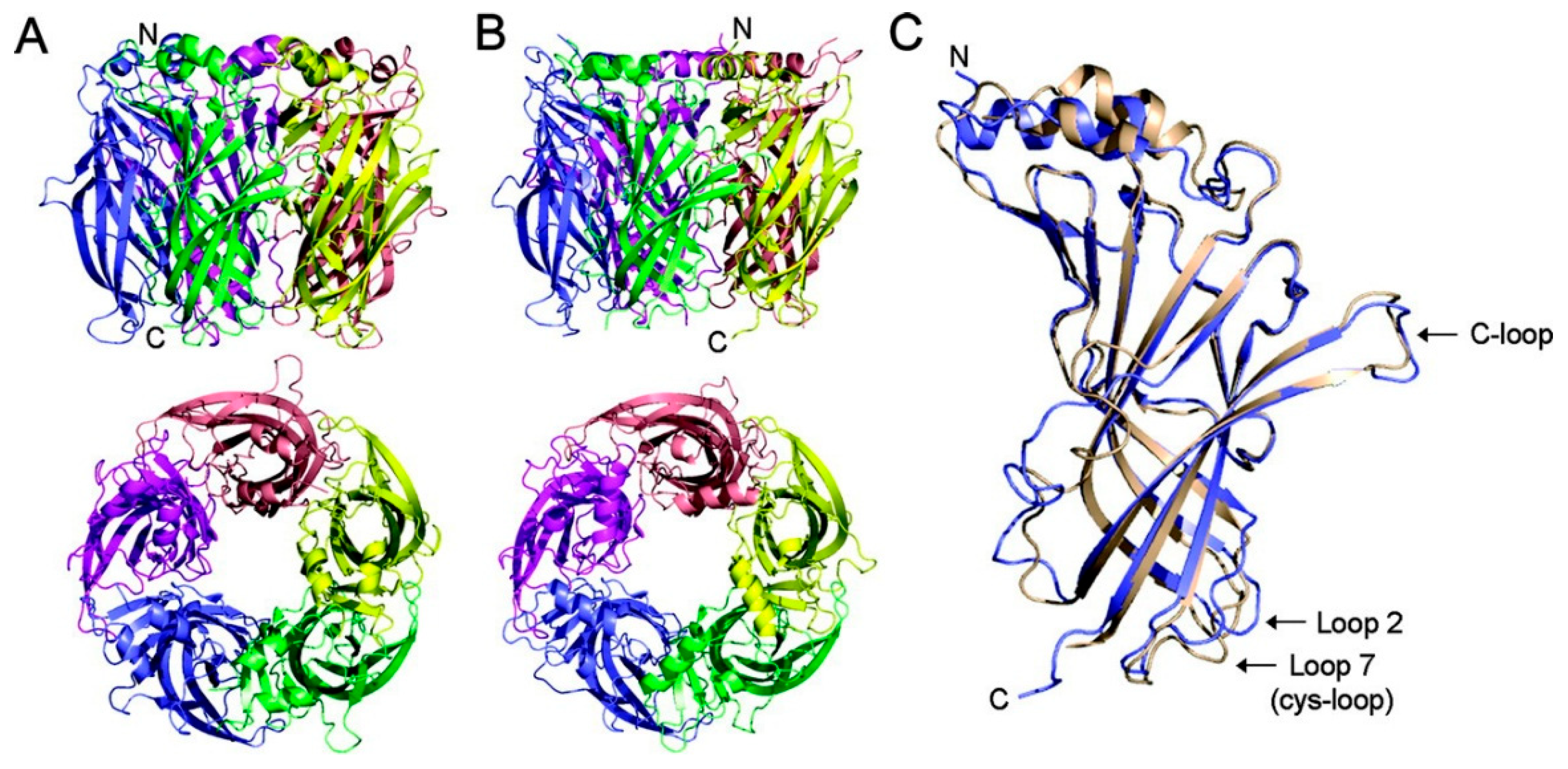

3.1. Bacterial Homologs

3.2. Cys-Loop Receptor Homologs

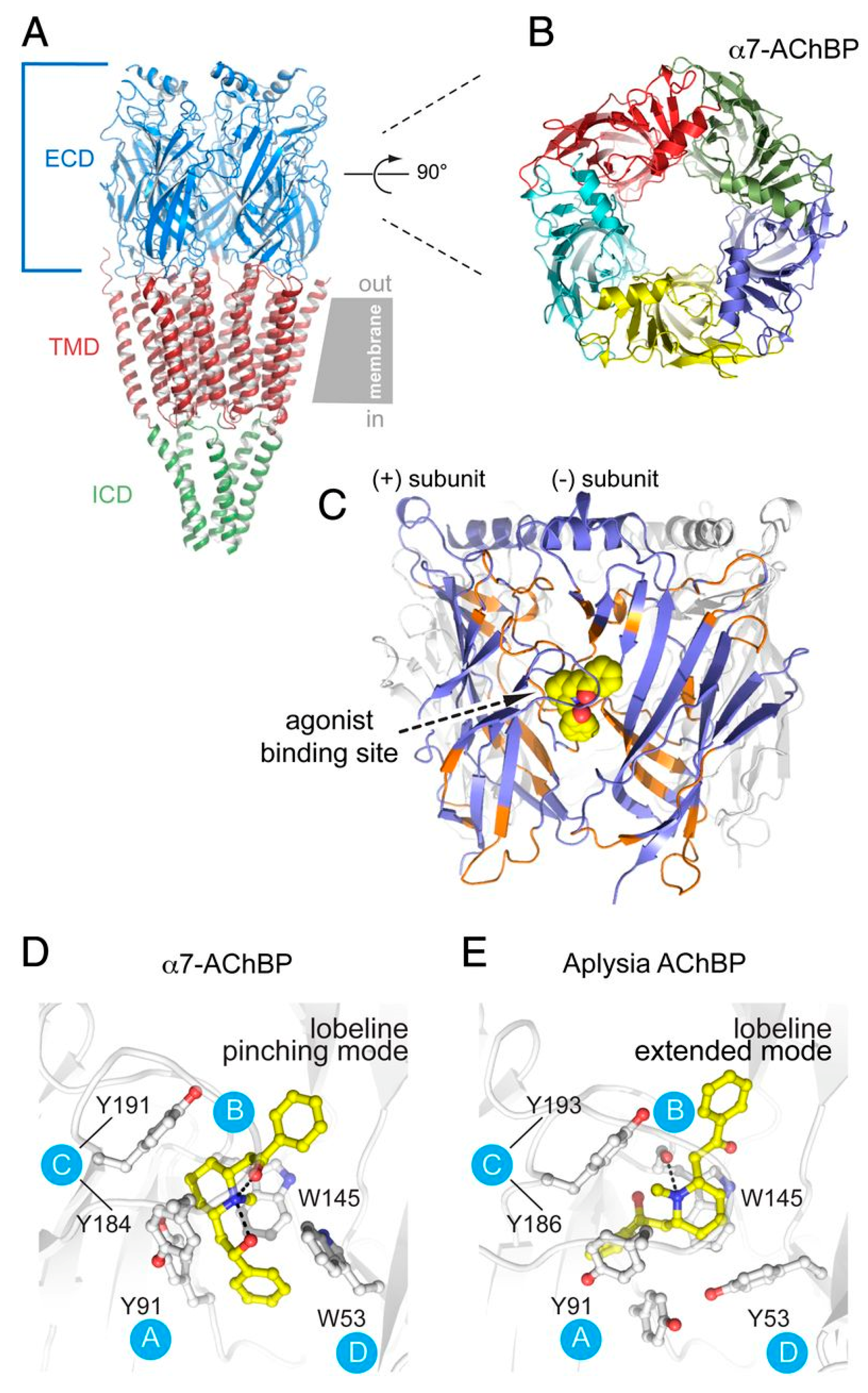

3.3. AChBP, a Soluble Homolog

4. Design and Engineering of Chimeras

5. Application of the Chimera Strategy

6. Summary

7. Conclusions and Limitations

8. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-HT3 | 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor or Serotonin type 3 receptor |

| Ac-AChBP | Aplysia californica Acetylcholine Binding Protein |

| AChBP | Acetylcholine Binding Protein |

| Bt-AChBP | Bulinus truncatus Acetylcholine Binding Protein |

| Cryo-EM | Cryo-Electron Microscopy |

| ECD | Extracellular Domain |

| ELIC | Erwinia Ligand Gated Ion Channel |

| GABA | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid |

| GLIC | Gloeobacter Ligand-gated Ion Channel |

| ICD | Intracellular Domain |

| LGICs | Ligand-gated Ion Channels |

| Ls-AChBP | Lymnaea stagnalis Acetylcholine Binding Protein |

| nAChRs | Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| PAMs | Positive Allosteric Modulators |

| pLGICs | Pentameric Ligand Gated Ion Channels |

| RIC-3 | Resistant to inhibitors of cholinesterase-3 |

| TMD | Transmembrane Domain |

| TMIE | Transmembrane Inner Ear |

References

- Alkondon, M.; Albuquerque, E.X. Initial Characterization of the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Rat Hippocampal Neurons. J. Recept. Res. 1991, 11, 1001–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElNebrisi, E.; Lozon, Y.; Oz, M. The Role of α7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3210. [Google Scholar]

- Majeed, S.; Ahmad, A.B.; Sehar, U.; Georgieva, E.R. Lipid Membrane Mimetics in Functional and Structural Studies of Integral Membrane Proteins. Membranes 2021, 11, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbowale, A.; Georgieva, E.R. Engineered Chimera Protein Constructs to Facilitate the Production of Heterologous Transmembrane Proteins in E. coli. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasco Serrão, V.H. Biological Breakthroughs and Drug Discovery Revolution via Cryo-Electron Microscopy of Membrane Proteins. Membranes 2025, 15, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Vélez, M.; Quesada, O.; Villalobos-Santos, J.C.; Maldonado-Hernández, R.; Asmar-Rovira, G.; Stevens, R.C.; Lasalde-Dominicci, J.A. Pursuing High-Resolution Structures of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors: Lessons Learned from Five Decades. Molecules 2021, 26, 5753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos-Santos, J.C.; Carrasquillo-Rivera, M.; Rodríguez-Cordero, J.A.; Quesada, O.; Lasalde-Dominicci, J.A. Insights into Crystallization of Neuronal Nicotinic α4β2 Receptor in Polarized Lipid Matrices. Crystals 2024, 14, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, V.; Wells, M.M.; Chen, Q.; Tillman, T.S.; Singewald, K.; Lawless, M.J.; Caporoso, J.; Brandon, N.; Coleman, J.A.; Saxena, S.; et al. Structures of highly flexible intracellular domain of human α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Indurthi, D.C.; Mittal, L.; Auerbach, A.; Asthana, S. Conformational dynamics of a nicotinic receptor neurotransmitter site. eLife 2024, 13, RP92418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krashia, P.; Moroni, M.; Broadbent, S.; Hofmann, G.; Kracun, S.; Beato, M.; Groot-Kormelink, P.J.; Sivilotti, L.G. Human α3β4 neuronal nicotinic receptors show different stoichiometry if they are expressed in Xenopus oocytes or mammalian HEK293 cells. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.J.; Bose, S.; Zwart, R.; Beattie, R.E.; Folly, E.A.; Johnson, L.R.; Bell, E.; Evans, N.M.; Benedetti, G.; Pearson, K.H.; et al. Stable expression and characterisation of a human α7 nicotinic subunit chimera: A tool for functional high-throughput screening. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 502, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotti, C.; Clementi, F.; Zoli, M. Auxiliary protein and chaperone regulation of neuronal nicotinic receptor subtype expression and function. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 200, 107067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, N.S.; Harkness, P.C. Assembly and trafficking of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (Review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 2008, 25, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unwin, N. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and the structural basis of neuromuscular transmission: Insights from Torpedo postsynaptic membranes. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2013, 46, 283–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulos, I.; Jabbour, J.; Khoury, S.; Mikhael, N.; Tishkova, V.; Candoni, N.; Ghadieh, H.E.; Veesler, S.; Bassim, Y.; Azar, S.; et al. Exploring the World of Membrane Proteins: Techniques and Methods for Understanding Structure, Function, and Dynamics. Molecules 2023, 28, 7176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberts, B.; Johnson, A.; Lewis, J.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walter, P. Analyzing protein structure and function. In Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th ed.; Garland Science: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, J.L.; Thompson, D.H. Challenges and opportunities for new protein crystallization strategies in structure-based drug design. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2010, 5, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharpure, A.; Noviello, C.M.; Hibbs, R.E. Progress in nicotinic receptor structural biology. Neuropharmacology 2020, 171, 108086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Gavi, S.; Wang, H.-y.; Malbon, C.C. Probing Receptor Structure/Function with Chimeric G-Protein-Coupled Receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004, 65, 1323–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Babcock, M.S.; Bode, J.; Chang, J.S.; Fischer, H.D.; Garlick, R.L.; Gill, G.S.; Lund, E.T.; Margolis, B.J.; Mathews, W.R.; et al. Affinity purification of a chimeric nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in the agonist and antagonist bound states. Protein Expr. Purif. 2011, 79, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurny, R.; Debaveye, S.; Farinha, A.; Veys, K.; Vos, A.M.; Gossas, T.; Atack, J.; Bertrand, S.; Bertrand, D.; Danielson, U.H.; et al. Molecular blueprint of allosteric binding sites in a homologue of the agonist-binding domain of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E2543–E2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouridakis, M.; Zisimopoulou, P.; Eliopoulos, E.; Poulas, K.; Tzartos, S.J. Design and expression of human α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor extracellular domain mutants with enhanced solubility and ligand-binding properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Proteins Proteom. 2009, 1794, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemecz, Á.; Taylor, P. Creating an α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Recognition Domain from the Acetylcholine-binding Protein: Crystallographic and Ligand Selectivity Analyses. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 42555–42565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixma, T.K.; Smit, A.B. Acetylcholine binding protein (AChBP): A secreted glial protein that provides a high-resolution model for the extracellular domain of pentameric ligand-gated ion channels. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2003, 32, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbart, F.; Brams, M.; Gruss, F.; Noppen, S.; Peigneur, S.; Boland, S.; Chaltin, P.; Brandao-Neto, J.; von Delft, F.; Touw, W.G.; et al. An allosteric binding site of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor revealed in a humanized acetylcholine-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 2534–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulens, C.; Akdemir, A.; Jongejan, A.; van Elk, R.; Bertrand, S.; Perrakis, A.; Leurs, R.; Smit, A.B.; Sixma, T.K.; Bertrand, D.; et al. Use of acetylcholine binding protein in the search for novel alpha7 nicotinic receptor ligands. In silico docking, pharmacological screening, and X-ray analysis. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 2372–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brejc, K.a.; van Dijk, W.J.; Klaassen, R.V.; Schuurmans, M.; van der Oost, J.; Smit, A.B.; Sixma, T.K. Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature 2001, 411, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Perez, C.L.; Noviello, C.M.; Hibbs, R.E. X-ray structure of the human α4β2 nicotinic receptor. Nature 2016, 538, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahsavar, A.; Ahring, P.K.; Olsen, J.A.; Krintel, C.; Kastrup, J.S.; Balle, T.; Gajhede, M. Acetylcholine-Binding Protein Engineered to Mimic the α4-α4 Binding Pocket in α4β2 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Reveals Interface Specific Interactions Important for Binding and Activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015, 88, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.N.T.; Abraham, N.; Lewis, R.J. Structure-Function of Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Inhibitors Derived from Natural Toxins. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 609005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Mesulam, M.M.; Cuello, A.C.; Farlow, M.R.; Giacobini, E.; Grossberg, G.T.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Vergallo, A.; Cavedo, E.; Snyder, P.J.; et al. The cholinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain J. Neurol. 2018, 141, 1917–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallés, A.S.; Barrantes, F.J. Dysregulation of Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor–Cholesterol Crosstalk in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 744597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olincy, A.; Freedman, R. Nicotinic mechanisms in the treatment of psychotic disorders: A focus on the α7 nicotinic receptor. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2012, 213, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzer-Serhan, U.H. Chapter 13—Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the autonomic nervous system. In Primer on the Autonomic Nervous System, 4th ed.; Biaggioni, I., Browning, K., Fink, G., Jordan, J., Low, P.A., Paton, J.F.R., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dani, J.A.; Bertrand, D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 47, 699–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.J.; Lester, H.A.; Lummis, S.C.R. The structural basis of function in Cys-loop receptors. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2010, 43, 449–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.K.; Sattelle, D.B. The cys-loop ligand-gated ion channel gene superfamily of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Invertebr. Neurosci. 2008, 8, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbs, R.E.; Zambon, A.C. Agents acting at the neuromuscular junction and autonomic ganglia. In Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 12th ed.; Mc Graw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 255–276. [Google Scholar]

- Jadey, S.V.; Purohit, P.; Bruhova, I.; Gregg, T.M.; Auerbach, A. Design and control of acetylcholine receptor conformational change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4328–4333. [Google Scholar]

- Sine, S.M. The nicotinic receptor ligand binding domain. J. Neurobiol. 2002, 53, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlin, A. Emerging structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, R.C.; Raggenbass, M.; Bertrand, D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: From structure to brain function. In Reviews of Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, A.B.; Kraus, G.P. Physiology, Cholinergic Receptors; StatPearls Publishing: Orlando, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.A. Acetylcholine and cholinergic receptors. Brain Neurosci. Adv. 2019, 3, 2398212818820506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipovsek, M.; Marcovich, I.; Elgoyhen, A.B. The Hair Cell α9α10 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor: Odd Cousin in an Old Family. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 785265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgoyhen, A.B. The α9α10 acetylcholine receptor: A non-neuronal nicotinic receptor. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 190, 106735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, E.X.; Pereira, E.F.; Alkondon, M.; Rogers, S.W. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: From structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 73–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkadas, E.; Pebay-Peyroula, E.; Thompson, M.J.; Schoehn, G.; Uchański, T.; Steyaert, J.; Chipot, C.; Dehez, F.; Baenziger, J.E.; Nury, H. Conformational transitions and ligand-binding to a muscle-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Neuron 2022, 110, 1358–1370.e1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, J.A. Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Structure and Function and Response to Nicotine. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2015, 124, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, D.A.; Karlin, A. Electrostatic potential of the acetylcholine binding sites in the nicotinic receptor probed by reactions of binding-site cysteines with charged methanethiosulfonates. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 6840–6849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, C.; Kaufmann, C.; Karlin, A. Negatively charged amino acid residues in the nicotinic receptor delta subunit that contribute to the binding of acetylcholine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 6285–6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unwin, N. Refined Structure of the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor at 4Å Resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 346, 967–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akk, G. Contributions of the non-alpha subunit residues (loop D) to agonist binding and channel gating in the muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J. Physiol. 2002, 544, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlin, A.; Akabas, M.H. Toward a structural basis for the function of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and their cousins. Neuron 1995, 15, 1231–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nys, M.; Kesters, D.; Ulens, C. Structural insights into Cys-loop receptor function and ligand recognition. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 86, 1042–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavar, A.; Gajhede, M.; Kastrup, J.S.; Balle, T. Structural studies of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Using acetylcholine-binding protein as a structural surrogate. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016, 118, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Chen, Q.; Willenbring, D.; Yoshida, K.; Tillman, T.; Kashlan, O.B.; Cohen, A.; Kong, X.-P.; Xu, Y.; Tang, P. Structure of the pentameric ligand-gated ion channel ELIC cocrystallized with its competitive antagonist acetylcholine. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiodo, L.; Malliavin, T.E.; Maragliano, L.; Cottone, G.; Ciccotti, G. A structural model of the human α7 nicotinic receptor in an open conformation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Ivanov, I.; Wang, H.; Sine, S.M.; McCammon, J.A. Molecular-Dynamics Simulations of ELIC—A Prokaryotic Homologue of the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Biophys. J. 2009, 96, 4502–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thompson, A.J.; Alqazzaz, M.; Ulens, C.; Lummis, S.C. The pharmacological profile of ELIC, a prokaryotic GABA-gated receptor. Neuropharmacology 2012, 63, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slobodyanyuk, M.; Banda-Vázquez, J.A.; Thompson, M.J.; Dean, R.A.; Baenziger, J.E.; Chica, R.A.; daCosta, C.J.B. Origin of acetylcholine antagonism in ELIC, a bacterial pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigg, D. Modeling ion channels: Past, present, and future. J. Gen. Physiol. 2014, 144, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, D.C.; Lummis, S.C. The molecular basis of the structure and function of the 5-HT3 receptor: A model ligand-gated ion channel (review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 2002, 19, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, D.C.; Goren, E.N.; Akabas, M.H.; Lummis, S.C.R. Structural and Electrostatic Properties of the 5-HT3Receptor Pore Revealed by Substituted Cysteine Accessibility Mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 42035–42042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, N.M.; Hales, T.G.; Lummis, S.C.; Peters, J.A. The 5-HT3 receptor—The relationship between structure and function. Neuropharmacology 2009, 56, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Oruganti, S.; Iyer, S.K.; Agarwal, K.; Gupta, M.; Adhikari, K.; Vijayan, N.; Doda, J.; Jain, V.; Lokhande, A.N.; et al. Effects of Swapping 5HT3 and α7 Residues in Chimeric Receptor Proteins on RIC3 and NACHO Chaperone Actions. Molecules 2025, 30, 4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxham, M.N. CHAPTER 11—Neurotransmitter Receptors. In From Molecules to Networks; Byrne, J.H., Roberts, J.L., Eds.; Academic Press: Burlington, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 299–334. [Google Scholar]

- Babakhani, A.; Talley, T.T.; Taylor, P.; McCammon, J.A. A virtual screening study of the acetylcholine binding protein using a relaxed-complex approach. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2009, 33, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdemir, A.; Rucktooa, P.; Jongejan, A.; Elk, R.v.; Bertrand, S.; Sixma, T.K.; Bertrand, D.; Smit, A.B.; Leurs, R.; de Graaf, C.; et al. Acetylcholine binding protein (AChBP) as template for hierarchical in silico screening procedures to identify structurally novel ligands for the nicotinic receptors. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 6107–6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, S.B.; Sulzenbacher, G.; Huxford, T.; Marchot, P.; Taylor, P.; Bourne, Y. Structures of Aplysia AChBP complexes with nicotinic agonists and antagonists reveal distinctive binding interfaces and conformations. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 3635–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulens, C.; Hogg, R.C.; Celie, P.H.; Bertrand, D.; Tsetlin, V.; Smit, A.B.; Sixma, T.K. Structural determinants of selective alpha-conotoxin binding to a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor homolog AChBP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 3615–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celie, P.H.N.; van Rossum-Fikkert, S.E.; van Dijk, W.J.; Brejc, K.; Smit, A.B.; Sixma, T.K. Nicotine and Carbamylcholine Binding to Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors as Studied in AChBP Crystal Structures. Neuron 2004, 41, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stober, S.T.; Abrams, C.F. Enhanced meta-analysis of acetylcholine binding protein structures reveals conformational signatures of agonism in nicotinic receptors. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 2012, 21, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaino, C.; Musgaard, M.; Minguez, T.; Mazzaferro, S.; Faundez, M.; Iturriaga-Vasquez, P.; Biggin, P.C.; Bermudez, I. Role of the Cys Loop and Transmembrane Domain in the Allosteric Modulation of α4β2 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhu, X.; Yu, J.; Yu, J.; Luo, S.; Wang, X. The crystal structure of Ac-AChBP in complex with α-conotoxin LvIA reveals the mechanism of its selectivity towards different nAChR subtypes. Protein Cell 2017, 8, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, A.B.; Syed, N.I.; Schaap, D.; van Minnen, J.; Klumperman, J.; Kits, K.S.; Lodder, H.; van der Schors, R.C.; van Elk, R.; Sorgedrager, B.; et al. A glia-derived acetylcholine-binding protein that modulates synaptic transmission. Nature 2001, 411, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celie, P.H.N.; Klaassen, R.V.; van Rossum-Fikkert, S.E.; van Elk, R.; van Nierop, P.; Smit, A.B.; Sixma, T.K. Crystal Structure of Acetylcholine-binding Protein from Bulinus truncatus Reveals the Conserved Structural Scaffold and Sites of Variation in Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 26457–26466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.; Salahudeen, A.A.; Jansen, M. Engineering a prokaryotic Cys-loop receptor with a third functional domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 34635–34642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H.; Fisher, D.I.; Roth, R.G.; Mark Abbott, W.; Carballo-Amador, M.A.; Warwicker, J.; Dickson, A.J. A protein chimera strategy supports production of a model “difficult-to-express” recombinant target. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 2499–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; Huang, S.; Bren, N.; Noridomi, K.; Dellisanti, C.D.; Sine, S.M.; Chen, L. Ligand-binding domain of an α7-nicotinic receptor chimera and its complex with agonist. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillman, T.S.; Seyoum, E.; Mowrey, D.D.; Xu, Y.; Tang, P. ELIC-α7 Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR) chimeras reveal a prominent role of the extracellular-transmembrane domain interface in allosteric modulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 13851–13857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, K.L.; Barnes, A.; Barnett, J.; Brown, A.; Cousens, D.; Dowell, S.; Green, A.; Patel, K.; Thomas, P.; Volpe, F.; et al. Complex chimeras to map ligand binding sites of GPCRs. Protein Eng. 2003, 16, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mnatsakanyan, N.; Nishtala, S.N.; Pandhare, A.; Fiori, M.C.; Goyal, R.; Pauwels, J.E.; Navetta, A.F.; Ahrorov, A.; Jansen, M. Functional Chimeras of GLIC Obtained by Adding the Intracellular Domain of Anion- and Cation-Conducting Cys-Loop Receptors. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 2670–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maue, R.A. Understanding ion channel biology using epitope tags: Progress, pitfalls, and promise. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007, 213, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickenden, A.D. Overview of Electrophysiological Techniques. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2000, 11, 11.1.1–11.1.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.M.; Avstrikova, M.; Noviello, C.M.; Mukhtasimova, N.; Changeux, J.-P.; Thakur, G.A.; Sine, S.M.; Cecchini, M.; Hibbs, R.E. Structural mechanisms of α7 nicotinic receptor allosteric modulation and activation. Cell 2024, 187, 1160–1176.e1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabasana, Z.; Perotin, J.-M.; Belgacemi, R.; Ancel, J.; Mulette, P.; Delepine, G.; Gosset, P.; Maskos, U.; Polette, M.; Deslée, G.; et al. Nicotinic Receptor Subunits Atlas in the Adult Human Lung. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eifler, N.; Duckely, M.; Sumanovski, L.T.; Egan, T.M.; Oksche, A.; Konopka, J.B.; Lüthi, A.; Engel, A.; Werten, P.J.L. Functional expression of mammalian receptors and membrane channels in different cells. J. Struct. Biol. 2007, 159, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.E.; Burton, B.; Urrutia, A.; Shcherbatko, A.; Chavez-Noriega, L.E.; Cohen, C.J.; Aiyar, J. Ric-3 promotes functional expression of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, G.; Morley, B.; Dwyer, D.; Bradley, R. Purification and Characterization of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors from Muscle. Membr. Biochem. 1980, 3, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostalova, Z.; Liu, A.; Zhou, X.; Farmer, S.L.; Krenzel, E.S.; Arevalo, E.; Desai, R.; Feinberg-Zadek, P.L.; Davies, P.A.; Yamodo, I.H.; et al. High-level expression and purification of Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channels in a tetracycline-inducible stable mammalian cell line: GABAA and serotonin receptors. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 2010, 19, 1728–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdin, B.; Segura, E.; Tétreault, M.P.; Lesage, S.; Parent, L. Determination of the Relative Cell Surface and Total Expression of Recombinant Ion Channels Using Flow Cytometry. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2016, 115, e54732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, MMott Grace; CWulffraat, Alex; JEddins, Ryan AMehl; Eric, N. Senning; Fluorescence labeling strategies for cell surface expression of TRPV1. J. Gen. Physiol. 2024, 156, e202313523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padula, M.P.; Berry, I.J.; O′Rourke, M.B.; Raymond, B.B.A.; Santos, J.; Djordjevic, S.P. A Comprehensive Guide for Performing Sample Preparation and Top-Down Protein Analysis. Proteomes 2017, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.J. Radioligand Binding Characterization of Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2008, 43, 1.8.1–1.8.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retra, K.; Geitmann, M.; Kool, J.; Smit, A.B.; de Esch, I.J.; Danielson, U.H.; Irth, H. Development of surface plasmon resonance biosensor assays for primary and secondary screening of acetylcholine binding protein ligands. Anal. Biochem. 2010, 407, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draczkowski, P.; Matosiuk, D.; Jozwiak, K. Isothermal titration calorimetry in membrane protein research. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 87, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucktooa, P.; Haseler, C.A.; van Elk, R.; Smit, A.B.; Gallagher, T.; Sixma, T.K. Structural characterization of binding mode of smoking cessation drugs to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors through study of ligand complexes with acetylcholine-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 23283–23293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patching, S.G. Surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy for characterisation of membrane protein–ligand interactions and its potential for drug discovery. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 2014, 1838, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumikawa, K.; Gehle, V.M. Assembly of mutant subunits of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor lacking the conserved disulfide loop structure. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 6286–6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrall, S.; Hall, Z.W. The N-terminal domains of acetylcholine receptor subunits contain recognition signals for the initial steps of receptor assembly. Cell 1992, 68, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eertmoed, A.L.; Green, W.N. Nicotinic receptor assembly requires multiple regions throughout the gamma subunit. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 6298–6308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, N.; Corradi, J.; Sine, S.M.; Bouzat, C. Stoichiometry for activation of neuronal α7 nicotinic receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20819–20824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayes, D.; Spitzmaul, G.; Sine, S.M.; Bouzat, C. Single-channel kinetic analysis of chimeric alpha7-5HT3A receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 68, 1475–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Zhou, Q.; Labroska, V.; Qin, S.; Darbalaei, S.; Wu, Y.; Yuliantie, E.; Xie, L.; Tao, H.; Cheng, J.; et al. G protein-coupled receptors: Structure- and function-based drug discovery. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papke, R.L.; Dwoskin, L.P.; Crooks, P.A.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, Z.; McIntosh, J.M.; Stokes, C. Extending the analysis of nicotinic receptor antagonists with the study of α6 nicotinic receptor subunit chimeras. Neuropharmacology 2008, 54, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huang, S.; Li, S.-X.; Bren, N.; Cheng, K.; Gomoto, R.; Chen, L.; Sine, S.M. Complex between α-bungarotoxin and an α7 nicotinic receptor ligand-binding domain chimaera. Biochem. J. 2013, 454, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figl, A.; Cohen, B.N.; Quick, M.W.; Davidson, N.; Lester, H.A. Regions of β4·β2 subunit chimeras that contribute to the agonist selectivity of neuronal nicotinic receptors. FEBS Lett. 1992, 308, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laverty, D.; Thomas, P.; Field, M.; Andersen, O.J.; Gold, M.G.; Biggin, P.C.; Gielen, M.; Smart, T.G. Crystal structures of a GABA(A)-receptor chimera reveal new endogenous neurosteroid-binding sites. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiselé, J.-L.; Bertrand, S.; Galzi, J.-L.; Devillers-Thiéry, A.; Changeux, J.-P.; Bertrand, D. Chimaeric nicotinic–serotonergic receptor combines distinct ligand binding and channel specificities. Nature 1993, 366, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.R.; Zwart, R.; Sher, E.; Millar, N.S. Pharmacological Properties of α9α10 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Revealed by Heterologous Expression of Subunit Chimeras. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004, 65, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.W.; McIntosh, J.M. α6 nAChR subunit residues that confer α-conotoxin BuIA selectivity. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2012, 26, 4102–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretter, V.; Ehya, N.; Fuchs, K.; Sieghart, W. Stoichiometry and Assembly of a Recombinant GABAA Receptor Subtype. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 2728–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Li, S.; Krezel, A.M.; Li, W. Stabilization and structure determination of integral membrane proteins by termini restraining. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 540–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Knowland, D.; Matta, J.A.; O’Carroll, M.L.; Davini, W.B.; Dhara, M.; Kweon, H.J.; Bredt, D.S. Hair cell α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor functional expression regulated by ligand binding and deafness gene products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 24534–24544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boero, L.E.; Castagna, V.C.; Di Guilmi, M.N.; Goutman, J.D.; Elgoyhen, A.B.; Gómez-Casati, M.E. Enhancement of the Medial Olivocochlear System Prevents Hidden Hearing Loss. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 7440–7451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, D.E.; Katz, E.; Maison, S.F.; Taranda, J.; Turcan, S.; Ballestero, J.; Liberman, M.C.; Elgoyhen, A.B.; Boulter, J. The alpha10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit is required for normal synaptic function and integrity of the olivocochlear system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20594–20599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, D.E.; Liberman, M.C.; Mann, J.; Barhanin, J.; Boulter, J.; Brown, M.C.; Saffiote-Kolman, J.; Heinemann, S.F.; Elgoyhen, A.B. Role of alpha9 nicotinic ACh receptor subunits in the development and function of cochlear efferent innervation. Neuron 1999, 23, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manetti, D.; Dei, S.; Arias, H.R.; Braconi, L.; Gabellini, A.; Teodori, E.; Romanelli, M.N. Recent Advances in the Discovery of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Allosteric Modulators. Molecules 2023, 28, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgoyhen, A.B. The α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: A compelling drug target for hearing loss? Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2022, 26, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Hernandez, G.A.; Taylor, P. Lessons from nature: Structural studies and drug design driven by a homologous surrogate from invertebrates, AChBP. Neuropharmacology 2020, 179, 108108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maelicke, A.; Ludwig, J.; Kaletta, T.; Höffle-Maas, A.; Samochocki, M.; Rabe, H. Directed Mutagenesis of Nicotinic Receptors to Investigate Receptor Function. In Genetic Manipulation of DNA and Protein—Examples from Current Research; Figurski, D., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, M.; Nishimura, O.; Nishimura, Y.; Kitaichi, M.; Kuraku, S.; Sone, M.; Hama, C. Control of Synaptic Levels of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor by the Sequestering Subunit Dα5 and Secreted Scaffold Protein Hig. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 3989–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen Ng, H.; Leggett, C.; Sakkiah, S.; Pan, B.; Ye, H.; Wu, L.; Selvaraj, C.; Tong, W.; Hong, H. Competitive docking model for prediction of the human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 binding of tobacco constituents. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 16899–16916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bouatta, N.; Sorger, P.; AlQuraishi, M. Protein structure prediction by AlphaFold2: Are attention and symmetries all you need? Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Struct. Biol. 2021, 77, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Adler, J.; Wu, Z.; Green, T.; Zielinski, M.; Žídek, A.; Bridgland, A.; Cowie, A.; Meyer, C.; Laydon, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction for the human proteome. Nature 2021, 596, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krokidis, M.G.; Koumadorakis, D.E.; Lazaros, K.; Ivantsik, O.; Exarchos, T.P.; Vrahatis, A.G.; Kotsiantis, S.; Vlamos, P. AlphaFold3: An Overview of Applications and Performance Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Shenoy, A.; Kundrotas, P.; Elofsson, A. Evaluation of AlphaFold-Multimer prediction on multi-chain protein complexes. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazas, P.V.; Katz, E.; Gomez-Casati, M.E.; Bouzat, C.; Elgoyhen, A.B. Stoichiometry of the alpha9alpha10 nicotinic cholinergic receptor. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 10905–10912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Ge, L.; Chen, X.; Lv, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, G. Beyond static structures: Protein dynamic conformations modeling in the post-AlphaFold era. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, R. AlphaFold2 and its applications in the fields of biology and medicine. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, V.; McShan, A.C. The power and pitfalls of AlphaFold2 for structure prediction beyond rigid globular proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2024, 20, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Ran, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Lin, P.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M. AlphaFold 3: An unprecedent opportunity for fundamental research and drug development. Precis. Clin. Med. 2025, 8, pbaf015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczepski, K.; Jaremko, Ł. AlphaFold and what is next: Bridging functional, systems and structural biology. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2025, 22, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcoran, W.K.; Cosio, A.; Edelstein, H.I.; Leonard, J.N. Exploring Structure—Function Relationships in Engineered Receptor Performance Using Computational Structure Prediction. GEN Biotechnol. 2025, 4, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirabello, C.; Wallner, B.; Nystedt, B.; Azinas, S.; Carroni, M. Unmasking AlphaFold to integrate experiments and predictions in multimeric complexes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurents, D.V. AlphaFold 2 and NMR Spectroscopy: Partners to Understand Protein Structure, Dynamics and Function. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 906437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S.N. | Chimera Composition | Structural Method and Resolution | Key Technical Details and Challenges | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i. | α7 nAChR/Ls-AChBP chimera, free (PDB code: 3SQ9) and Epibatidine bound (PDB code: 3SQ6) | X-ray Crystallography (Apo—3.10 Å Epi bound—2.80 Å) | Construct design: N-terminal and Cys-loop of AChBP fused with the remaining ECD of α7; 64% sequence identity with native α7 nAChRs. Expression: Pichia pastoris Challenges: Native α7 ECD failed to express in yeast; multiple chimera iterations were required. Success factors: Strategic inclusion of AChBP segments improved expression; Epi stabilized crystals diffracted better. Validation method: Radioligand binding | First high-resolution structure of α7 ligand binding domain: Mechanistic insight into agonist binding, signal transduction, template for drug design targeting α7 nAChRs [80] |

| ii. | α7 nAChR/AChBP chimera complex with α-BTX (PDB code: 4HQP) | X-ray Crystallography (3.51 Å) | Construct design: same as entry (i) Challenge: Glycan chains interfered with crystal formation, requiring Endo HF deglycosylation to obtain diffracting crystals Success factor: Chimera expressed stable pentamers and bound α-BTX with high affinity. Comparison with the agonist-bound structure 3SQ6 showed that α-BTX binding locks loop C in a uniformly open conformation, in contrast to the closed-in loop C conformation observed with epibatidine. Validation method: Radioligand binding | Understanding toxin interaction with α7 subtypes and comparison with agonist-bound structure [107] |

| iii. | α7 nAChR/Ls-AChBP chimera (PDB code: 5OUH, 5OUG, 5OUI) | X-ray Crystallography (2.5–3.10Å) | Construct design: same as entry (i) Expression: Sf9 insect cells Challenges: PAMs’ binding site initially cryptic, required screening of a large fragment collection Success factors: Automated collection of diffraction data from thousands of fragments-soaked crystals Validation method: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Electrophysiology | Identification of a novel allosteric binding site for PAMs [25] |

| iv. | α7 nAChR/AChBP chimera (PDB code: 5AFH, 5AFJ, 5AFK, 5AFL, 5AFM, 5AFN) | X-ray Crystallography (2.15–2.85Å) | Construct design: same as entry (i) Fragment library screening: Tested diverse chemical scaffolds. Expression: Sf21 insect cells Challenges: Low fragment affinity Success factors: Lobeline co-crystallization helped stabilize the structure and revealed an induced fit mechanism. Validation method: SPR Electrophysiology | Identification of three allosteric binding sites in the ECD of α7 nAChRs and associated conformational dynamics utilizing a fragment-based drug screening approach [21] |

| v. | α7 nAChR/5-HT3 receptor chimera | ND | Construct design: N-terminal part of α7 combined with the C-terminal region of 5-HT3 subunit. Challenges: Several chimeras had to be built with optimization of junction residues Success factor: At least one construct expressed a functional receptor with α7-like nicotinic ligand binding properties and 5-HT3-like channel properties, potentiated by external Ca2+ ions. Validation method: Electrophysiology, Radioligand binding | Demonstrated the possibility of fusing ECD of α7 nAChRs with TMD and ICD of serotonin receptors for functional expression and identifying molecular determinants for ligand binding and channel gating in the α7 nAChR subtype [110] |

| vi. | Human α7 nAChR/mouse 5-HT3 receptor chimera | ND | Chimera construct: ECD of α7 fused with TMD and the C-terminal region of 5-HT3. Expression: HEK-293 cells Challenge: Wild-type α7 exhibited poor, stable expression Success factors: Stable cell line development, 129 chimera clones screened for functional expression, clones with large Ca2+ response selected for imaging. Validation method: Electrophysiological assay Fluorescent binding assay High-throughput Calcium Imaging | Stable mammalian expression, a tool for functional high-throughput screening [11] |

| vii. | Rat α9 or α10 nAChR subunit/mouse 5-HT3A receptor chimera | ND | Chimera construct: ECD of α9 or α10 fused to the C-terminal region of 5-HT3A. Expression: HEK-293 cells, Xenopus laevis oocytes Challenge: Mammalian cells transfected with native α9 or α10 cDNAs alone or expressed showed no expression Success factor: Successful co-expression of α9 and α10 chimera Validation method: Electrophysiology Radioligand binding assay | First functional expression of α9 and α10 receptors alone in mammalian cell lines and their co-expression, to dissect the role of each subunit in ligand binding; model to study native α9α10 nAChRs [111] |

| viii. | ELIC/α7 nAChR | ND | Chimera Construct: Multiple chimeras generated between ELIC (ECD) and α7 (TMD), with systematic swaps of interface elements. Challenge: Most constructions showed no response Success factor: Only the construct preserving specific interface residues in α7 showed PAM potentiation. Validation method: Electrophysiology | Role of ECD-TMD interface in allosteric modulation [81] |

| ix. | α6/α4 nAChR chimera | ND | Chimera Construct: ECD of α6 litigated with the remaining parts of the α4 subunit. Challenge: α6 does not form a functional receptor with the β2 subunit Success factor: α6/α4 chimera injected together with β2, retained α6-specific properties while achieving functional expression. Validation method: Electrophysiology | Determination of amino acid residues driving selectivity of neurotoxin, α-conotoxin BuIA, between α6 and α4 subunits [106,112] |

| x. | β4/β2 nAChR chimera | ND | Chimera construct: N-terminal of β4 combined with C-terminal of β2 and co-expressed with α3 in oocytes. Challenge: Required systematic testing of multiple chimera designs Success factor: Identified regions of β subunits critical for agonist sensitivity, revealed that β subunits actively contribute to receptor pharmacology, not just the α subunit. Validation method: Electrophysiology | Investigating interface contributions to ligand binding, subtype pharmacology, and ligand selectivity [108] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sapkota, P.; Akaberi, S.M.; Ghimire, B.; Sharma, K. Chimeric Approach to Identify Molecular Determinants of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021091

Sapkota P, Akaberi SM, Ghimire B, Sharma K. Chimeric Approach to Identify Molecular Determinants of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021091

Chicago/Turabian StyleSapkota, Pooja, Seyedeh Melika Akaberi, Biwash Ghimire, and Kavita Sharma. 2026. "Chimeric Approach to Identify Molecular Determinants of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021091

APA StyleSapkota, P., Akaberi, S. M., Ghimire, B., & Sharma, K. (2026). Chimeric Approach to Identify Molecular Determinants of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021091