Effect of Melatonin and Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Combination on In Vitro Maturation of Mouse Oocytes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Different Antioxidants on the PB1 Extrusion Rate in Mouse Oocytes

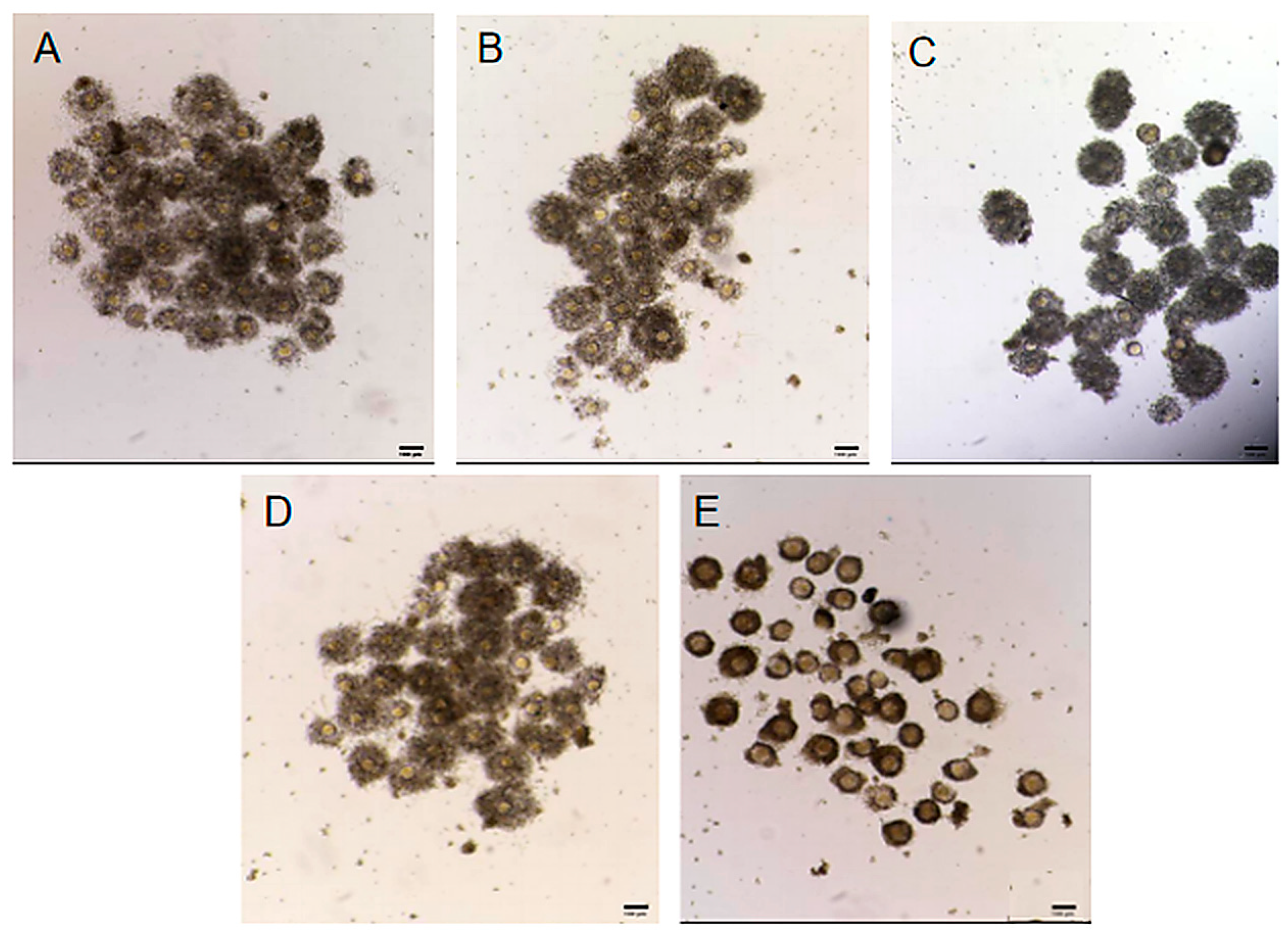

2.2. Effect of Different Antioxidants on Cumulus Cell Expansion

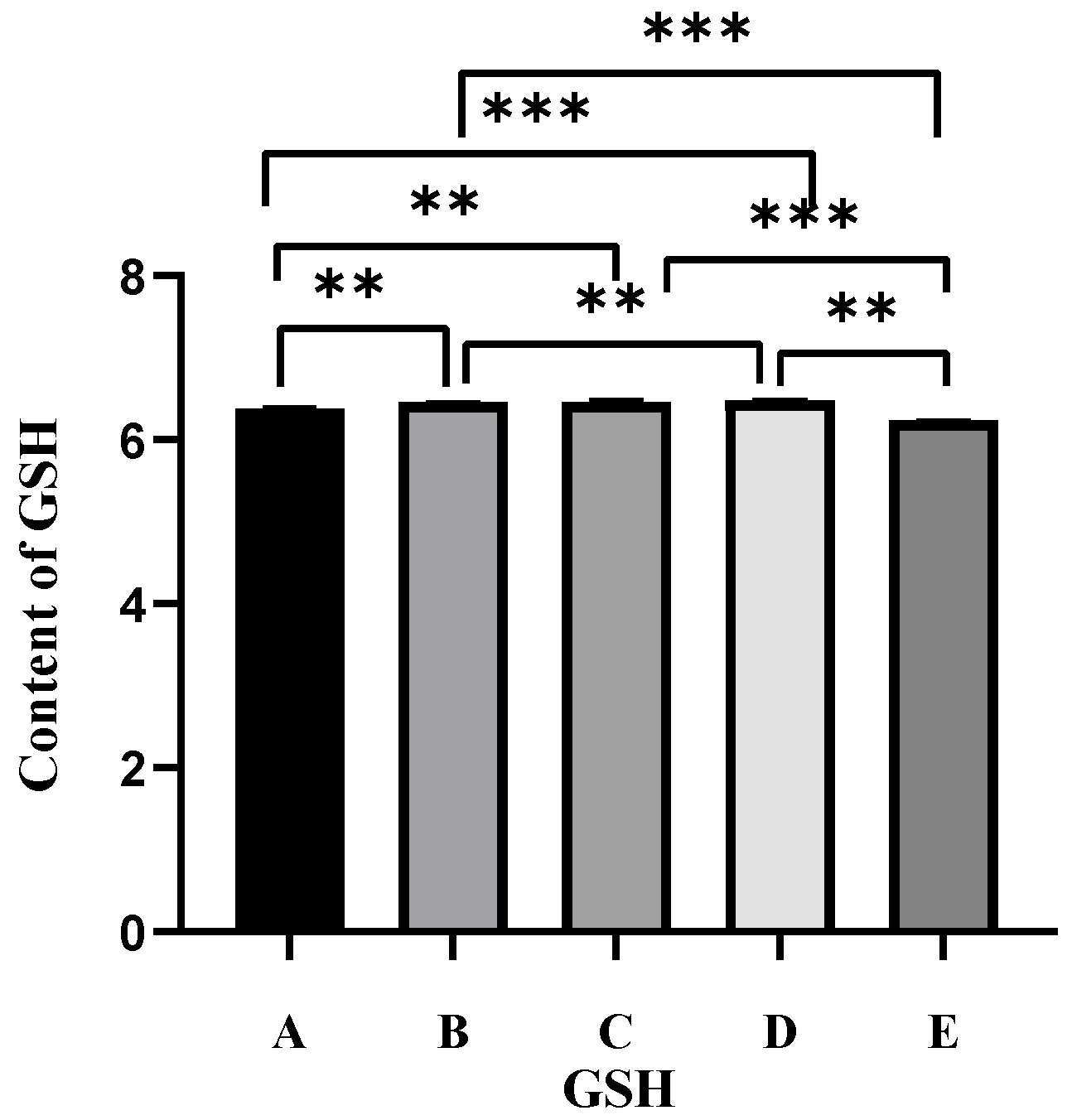

2.3. Effect of Different Antioxidants on GSH Levels in Oocytes

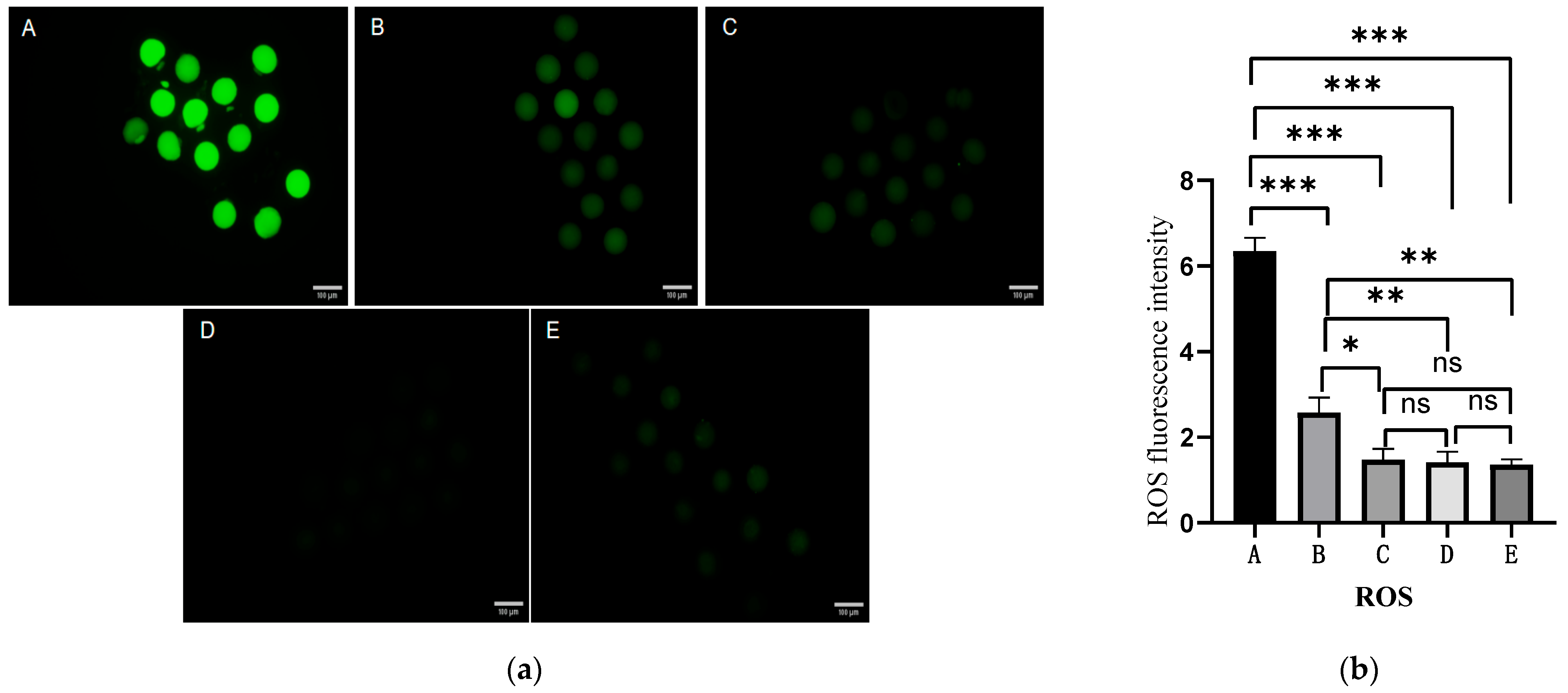

2.4. Effect of Different Antioxidants on ROS Levels in Oocytes

2.5. Effect of Different Antioxidants on the Cleavage and Blastocyst Rates

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Oocyte Collection

4.2. IVM and IVF

4.3. Determination of the PB1 Extrusion Rate

4.4. Cumulus Cell Expansion

4.5. Detection of ROS Levels

4.6. Estimation of GSH Levels

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, P.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, X.; Yao, L.; Ning, J.; Han, X.; Ming, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L. UCH-L1 inhibitor LDN-57444 hampers mouse oocyte maturation by regulating oxidative stress and mitochondrial function and reducing ERK1/2 expression. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20201308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.F.; Qi, S.T.; Xian, Y.X.; Huang, L.; Sun, X.F.; Wang, W.H. Protective effect of antioxidants on the pre-maturation aging of mouse oocytes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.; Gardner, D.K. Antioxidants improve IVF outcome and subsequent embryo development in the mouse. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 2404–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Chang, Q.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Chen, Z.; Jiao, X.; Guo, Y.; Teng, X. Relationship of the levels of reactive oxygen species in the fertilization medium with the outcome of in vitro fertilization following brief incubation. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1133566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, S.; Singh, S.; Sharma, P. Chapter 19—Role of antioxidants in neutralizing oxidative stress. In Nutraceutical Fruits and Foods for Neurodegenerative Disorders; Keservani, R.K., Kesharwani, R.K., Emerald, M., Sharma, A.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 353–378. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarzi, S.; Salehi, M.; Farifteh-Nobijari, F.; Hosseini, T.; Hosseini, S.; Ghazifard, A.; Ghaffari, N.M.; Fallah-Omrani, V.; Nourozian, M.; Hosseini, A. Melatonin Modifies Histone Acetylation During In Vitro Maturation of Mouse Oocytes. Cell J. 2018, 20, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Hua, C.; Ci, X. Melatonin alleviates particulate matter-induced liver fibrosis by inhibiting ROS-mediated mitophagy and inflammation via Nrf2 activation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 268, 115717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikmard, F.; Hosseini, E.; Bakhtiyari, M.; Ashrafi, M.; Amidi, F.; Aflatoonian, R. The boosting effects of melatonin on the expression of related genes to oocyte maturation and antioxidant pathways: A polycystic ovary syndrome-mouse model. J. Ovarian Res. 2022, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.; Manchester, L.C.; Esteban-Zubero, E.; Zhou, Z.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin as a Potent and Inducible Endogenous Antioxidant: Synthesis and Metabolism. Molecules 2015, 20, 18886–18906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Li, C.; Yan, C.; Liu, N.; Jiang, G.; Yang, H.; Yan, H.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Gao, C. Melatonin alleviates early brain injury by inhibiting the NRF2-mediated ferroptosis pathway after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 208, 555–570, Erratum in Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 228, 403–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2024.12.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, T.; Wu, H.; Yang, N.; Xu, S. Melatonin attenuates bisphenol A-induced colon injury by dual targeting mitochondrial dynamics and Nrf2 antioxidant system via activation of SIRT1/PGC-1α signaling pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 195, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melhuish Beaupre, L.M.; Brown, G.M.; Goncalves, V.F.; Kennedy, J.L. Melatonin’s neuroprotective role in mitochondria and its potential as a biomarker in aging, cognition and psychiatric disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortezaee, K.; Najafi, M.; Farhood, B.; Ahmadi, A.; Potes, Y.; Shabeeb, D.; Musa, A.E. Modulation of Apoptosis by Melatonin for Improving Cancer Treatment Efficiency: An Updated Review. Life Sci. 2019, 228, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Ma, Y.; Tao, Z.; Qiu, S.; Gong, Z.; Tao, L.; Zhu, Y. Melatonin Inhibits Glucose-Induced Apoptosis in Osteoblastic Cell Line Through PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 602307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Yang, S.G.; Jung, J.M.; Kim, M.J.; Kang, M.J.; Cho, Y.H.; Wee, G.; Yang, H.Y.; et al. Melatonin improves the meiotic maturation of porcine oocytes by reducing endoplasmic reticulum stress during in vitro maturation. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 64, e12458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; He, C.; Ji, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, D.; Abulizi, W.; Wang, X.; et al. Beneficial Effects of Melatonin on the In Vitro Maturation of Sheep Oocytes and Its Relation to Melatonin Receptors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Shan, X.; Jiang, H.; Guo, Z. Exogenous Melatonin Directly and Indirectly Influences Sheep Oocytes. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 903195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Q.; Peng, W.; Cheng, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Su, J. Melatonin supplementation during in vitro maturation of oocyte enhances subsequent development of bovine cloned embryos. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 17370–17381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Yang, S.G.; Kim, M.J.; Jegal, H.G.; Kim, I.S.; Choo, Y.K.; Koo, D.B. Melatonin Improves Oocyte Maturation and Mitochondrial Functions by Reducing Bisphenol A-Derived Superoxide in Porcine Oocytes In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.; Ali, S.; Ashraf, G.M.; Bilgrami, A.L.; Yadav, D.K.; Hassan, M.I. Epigallocatechin 3-gallate: From green tea to cancer therapeutics. Food Chem. 2022, 379, 132135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmann, J.; Buer, J.; Pietschmann, T.; Steinmann, E. Anti-infective properties of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a component of green tea. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 168, 1059–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Pang, Y.; Hao, H.; Du, W.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, H. Effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate on bovine oocytes matured in vitro. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, L.; Zhang, A.; Lv, D.; Cong, L.; Sun, Z.; Liu, L. EGCG activates Keap1/P62/Nrf2 pathway, inhibits iron deposition and apoptosis in rats with cerebral hemorrhage. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Li, C.; Gao, F.; Fan, Y.; Zeng, F.; Meng, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Wei, H. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Promotes the in vitro Maturation and Embryo Development Following IVF of Porcine Oocytes. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2021, 15, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Su, W.; Zhao, R.; Li, M.; Zhao, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, H. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate improves the quality of maternally aged oocytes. Cell Prolif. 2024, 57, e13575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriphap, A.; Kiddee, A.; Duangjai, A.; Yosboonruang, A.; Pook-In, G.; Saokaew, S.; Sutheinkul, O.; Rawangkan, A. Antimicrobial Activity of the Green Tea Polyphenol (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) against Clinical Isolates of Multidrug-Resistant Vibrio cholerae. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Huang, C.; Zheng, G.; Yi, W.; Wu, B.; Tang, J.; Liu, X.; Huang, B.; Wu, D.; Yan, T.; et al. EGCG Inhibits Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis Through Downregulation of SIRT1 in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Cells. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 851972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, H.; Liu, C.; Shi, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; He, Y.; Tao, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, R. EGCG Alleviates Obesity-Induced Myocardial Fibrosis in Rats by Enhancing Expression of SCN5A. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 869279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, K.; Yang, C.S.; Reiter, R.J.; Zhang, J. Melatonin and (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate: Partners in Fighting Cancer. Cells 2019, 8, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J.; Kang, H.; Jeon, S.; Yun, J.H.; Jeong, P.; Sim, B.; Kim, S.; Cho, S.; Song, B. The antioxidant betulinic acid enhances porcine oocyte maturation through Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway modulation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e311819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jia, Y.; Meng, S.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Q.; Pan, Z. Mechanisms of and Potential Medications for Oxidative Stress in Ovarian Granulosa Cells: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.; Lee, S.; Park, M.; Han, D.; Lee, H.; Ryu, B.; Kim, E.; Park, S. Piperine improves the quality of porcine oocytes by reducing oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 213, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wei, Y.; Wang, T.; Wan, X.; Yang, C.S.; Reiter, R.J.; Zhang, J. Melatonin attenuates (-)-epigallocatehin-3-gallate-triggered hepatotoxicity without compromising its downregulation of hepatic gluconeogenic and lipogenic genes in mice. J. Pineal Res. 2015, 59, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Sun, J.; Bu, S.; Li, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Lai, D. Melatonin protects against chronic stress-induced oxidative meiotic defects in mice MII oocytes by regulating SIRT1. Cell Cycle 2020, 19, 1677–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Li, X.; Ge, J.; Reiter, R.J.; Wang, Q. Melatonin protects against maternal obesity-associated oxidative stress and meiotic defects in oocytes via the SIRT3-SOD2-dependent pathway. J. Pineal Res. 2017, 63, e12431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Shi, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, H. Applications of Melatonin in Female Reproduction in the Context of Oxidative Stress. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6668365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.N.; Shankar, S.; Srivastava, R.K. Green tea catechin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG): Mechanisms, perspectives and clinical applications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011, 82, 1807–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sun, Q. Evaluation of oocyte quality: Morphological, cellular and molecular predictors. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2007, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuelke, K.A.; Jones, D.P.; Perreault, S.D. Glutathione oxidation is associated with altered microtubule function and disrupted fertilization in mature hamster oocytes. Biol. Reprod. 1997, 57, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turathum, B.; Gao, E.M.; Chian, R.C. The Function of Cumulus Cells in Oocyte Growth and Maturation and in Subsequent Ovulation and Fertilization. Cells 2021, 10, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghantabpour, T.; Goudarzi, N.; Parsaei, H. Overview of Nrf2 as a target in ovary and ovarian dysfunctions focusing on its antioxidant properties. J. Ovarian Res. 2025, 18, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Cha, D.; Jang, S.J.; Cho, J.; Moh, S.H.; Lee, S. Redox Control of Nrf2 Signaling in Oocytes Harnessing Porphyra Derivatives As a Toggle. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 227, 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozdemir, N.; Cakir, C.; Cinar, O.; Cinar, F.U. Antioxidant-supplemented Media Modulates ROS by Regulating Complex I During Mouse Oocyte Maturation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Ma, N.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Wan, B.; Lu, W. Melatonin Biosynthesis and Regulation in Reproduction. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1630164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderhyden, B.C.; Caron, P.J.; Buccione, R.; Eppig, J.J. Developmental pattern of the secretion of cumulus expansion-enabling factor by mouse oocytes and the role of oocytes in promoting granulosa cell differentiation. Dev. Biol. 1990, 140, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, Y.; Feng, Q.; Shi, W.; Fang, Y.; Hung, J.; Shi, D. Effects of Sodium Selenite on the in vitro Maturation of Porcine Oocytes and Their Embryonic Development Potentials. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2024, 57, 3482–3493. [Google Scholar]

| Group | Number of Oocytes | PB1 Extrusion Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Control group | 126 | 66.66 ± 0.51 b |

| Melatonin group | 128 | 89.79 ± 0.58 a |

| EGCG group | 134 | 89.56 ± 0.40 a |

| Half-dose combination group | 125 | 91.96 ± 0.57 a |

| Brusatol group | 129 | 22.43 ± 0.98 c |

| Group | Cumulus Expansion Index |

|---|---|

| Control group | 3.02 ± 0.03 a |

| Melatonin group | 3.03 ± 0.05 a |

| EGCG group | 3.02 ± 0.04 a |

| Half-dose combination group | 3.06 ± 0.05 a |

| Brusatol group | 1.87 ± 0.05 b |

| Group | Number of Embryos | Cleavage Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Control group | 102 | 56.82 ± 0.44 b |

| Melatonin group | 95 | 65.31 ± 0.51 a |

| EGCG group | 102 | 63.74 ± 0.31 a |

| Half-dose combination group | 97 | 75.23 ± 0.39 a |

| Brusatol group | 99 | 17.12 ± 1.00 c |

| Group | Number of Embryos | Blastocyst Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Control group | 72 | 30.94 ± 0.28 b |

| Melatonin group | 74 | 46.88 ± 0.42 b |

| EGCG group | 76 | 44.85 ± 0.23 b |

| Half-dose combination group | 75 | 53.97 ± 0.47 a |

| Brusatol group | 70 | 4.45 ± 0.33 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Y. Effect of Melatonin and Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Combination on In Vitro Maturation of Mouse Oocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021089

Li S, Chen L, Li Y, Xu L, Chen Y, Ma Y. Effect of Melatonin and Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Combination on In Vitro Maturation of Mouse Oocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021089

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shuangshuang, Lili Chen, Yi Li, Lingyang Xu, Yan Chen, and Yi Ma. 2026. "Effect of Melatonin and Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Combination on In Vitro Maturation of Mouse Oocytes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021089

APA StyleLi, S., Chen, L., Li, Y., Xu, L., Chen, Y., & Ma, Y. (2026). Effect of Melatonin and Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Combination on In Vitro Maturation of Mouse Oocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021089