Triamcinolone Modulates Chondrocyte Biomechanics and Calcium-Dependent Mechanosensitivity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

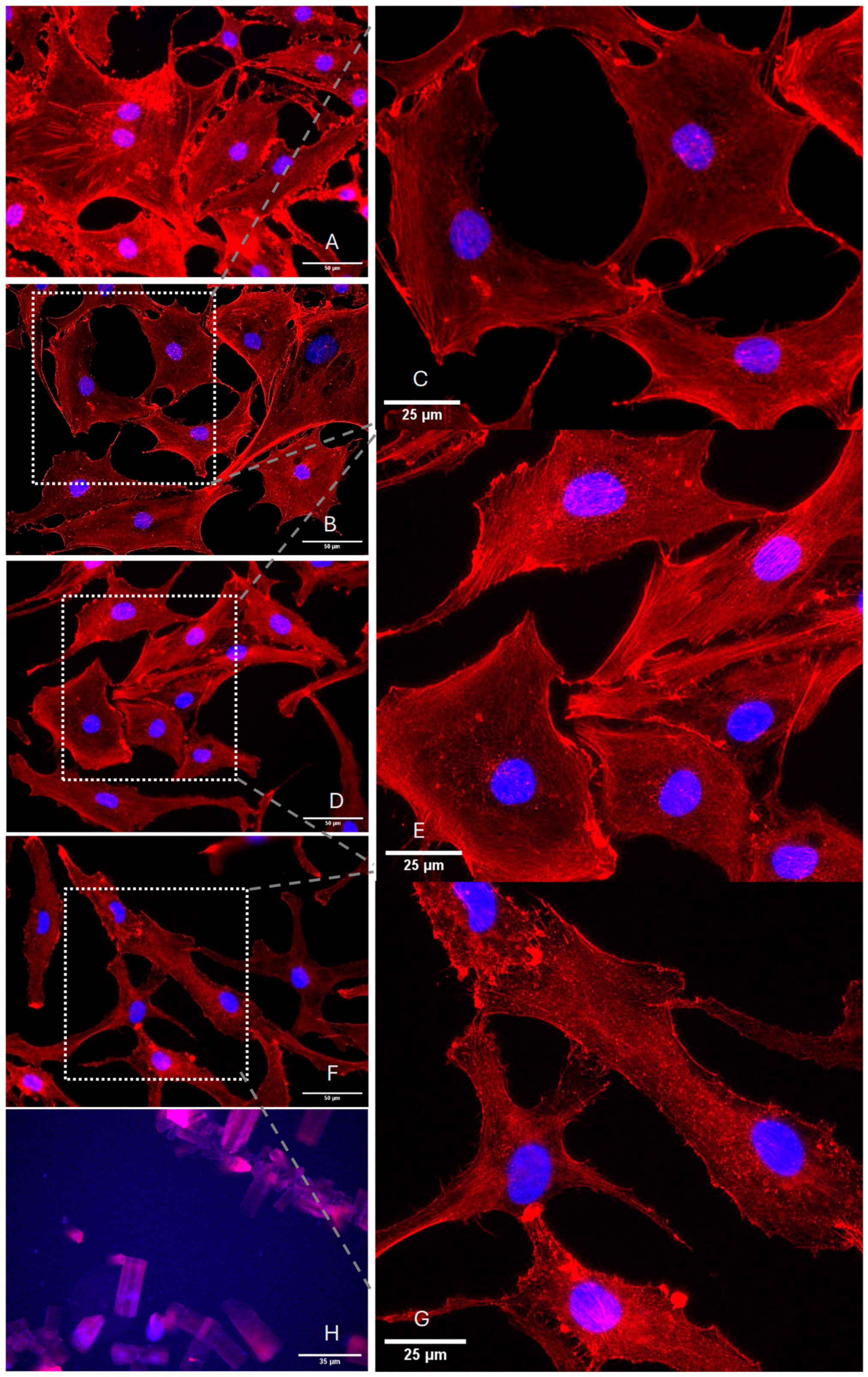

2.1. Determination of Optimal TA Concentrations for Effective Experimental Outcomes

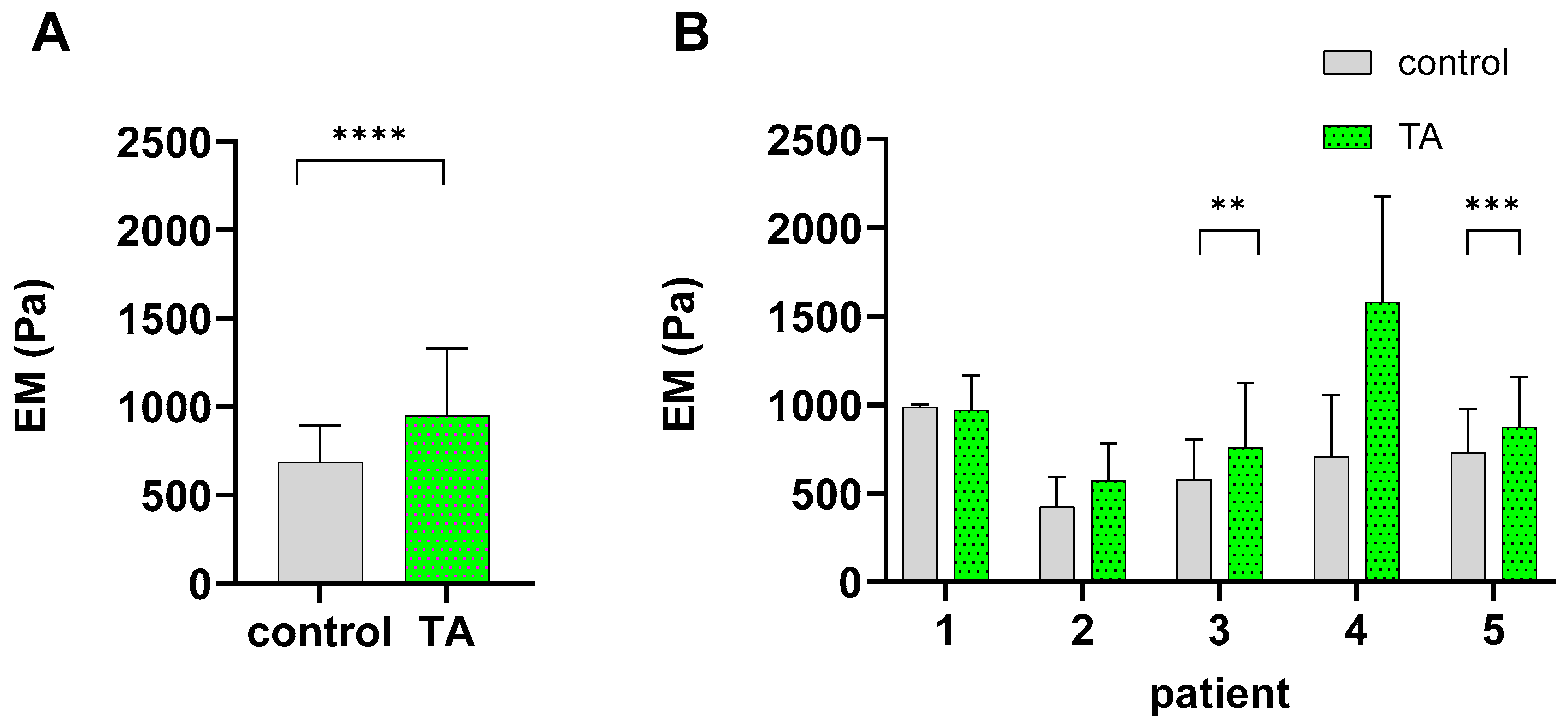

2.2. TA Alters the Biomechanical Characteristics of Chondrocytes

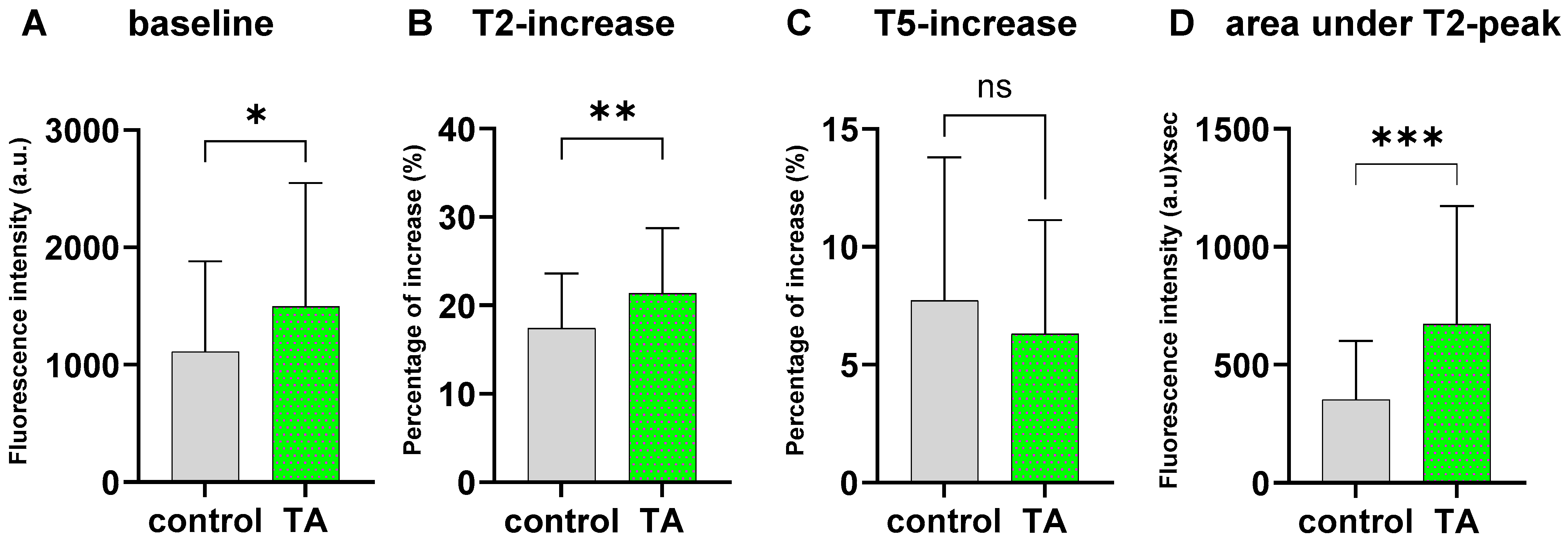

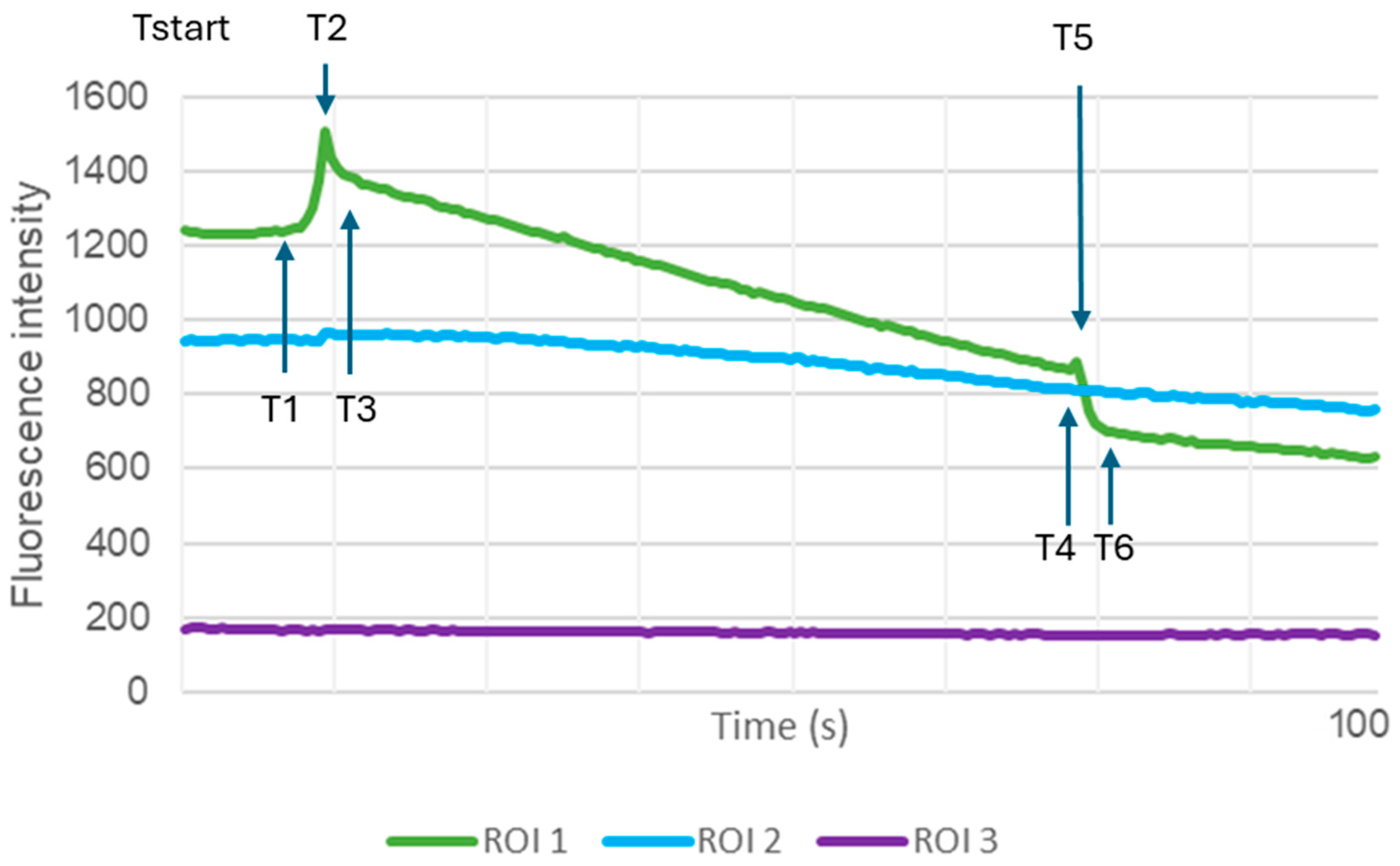

2.3. TA Treatment Significantly Alters Ca2+ Dynamics During Mechanical AFM Stimulation

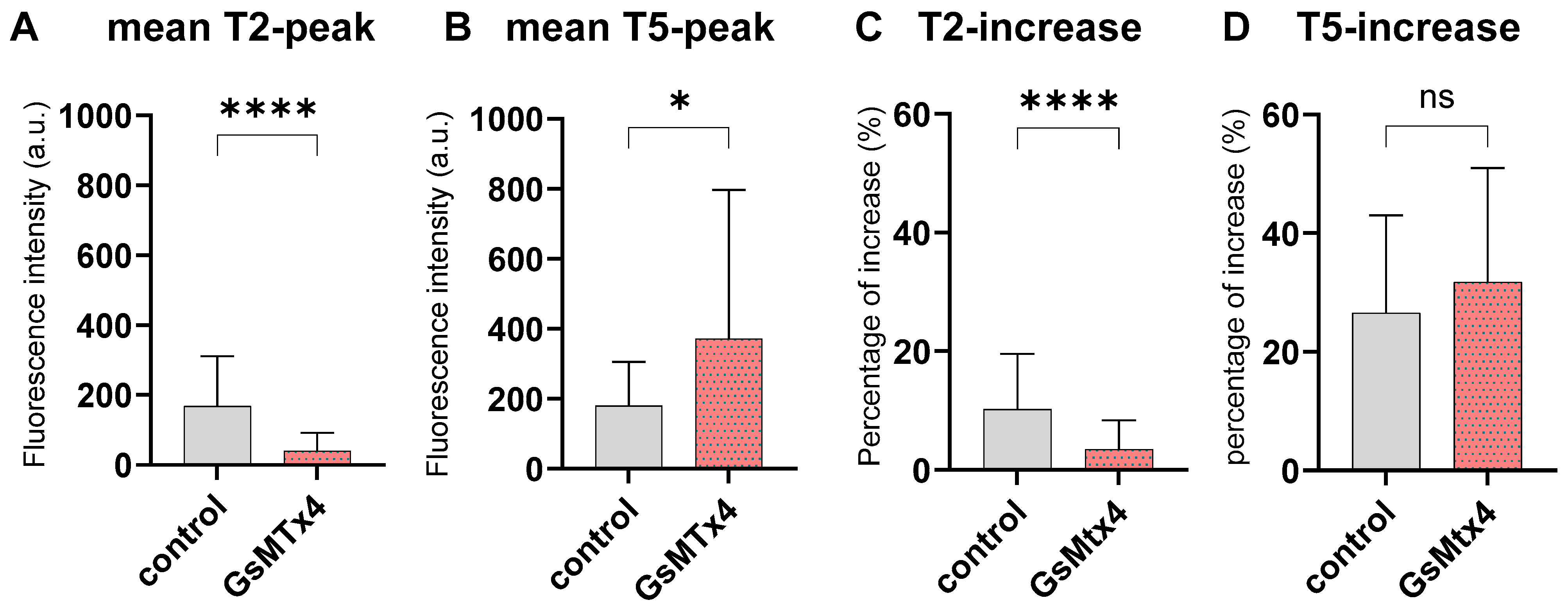

2.4. Inhibition of Mechano-Calcium Receptor by GsMtx4

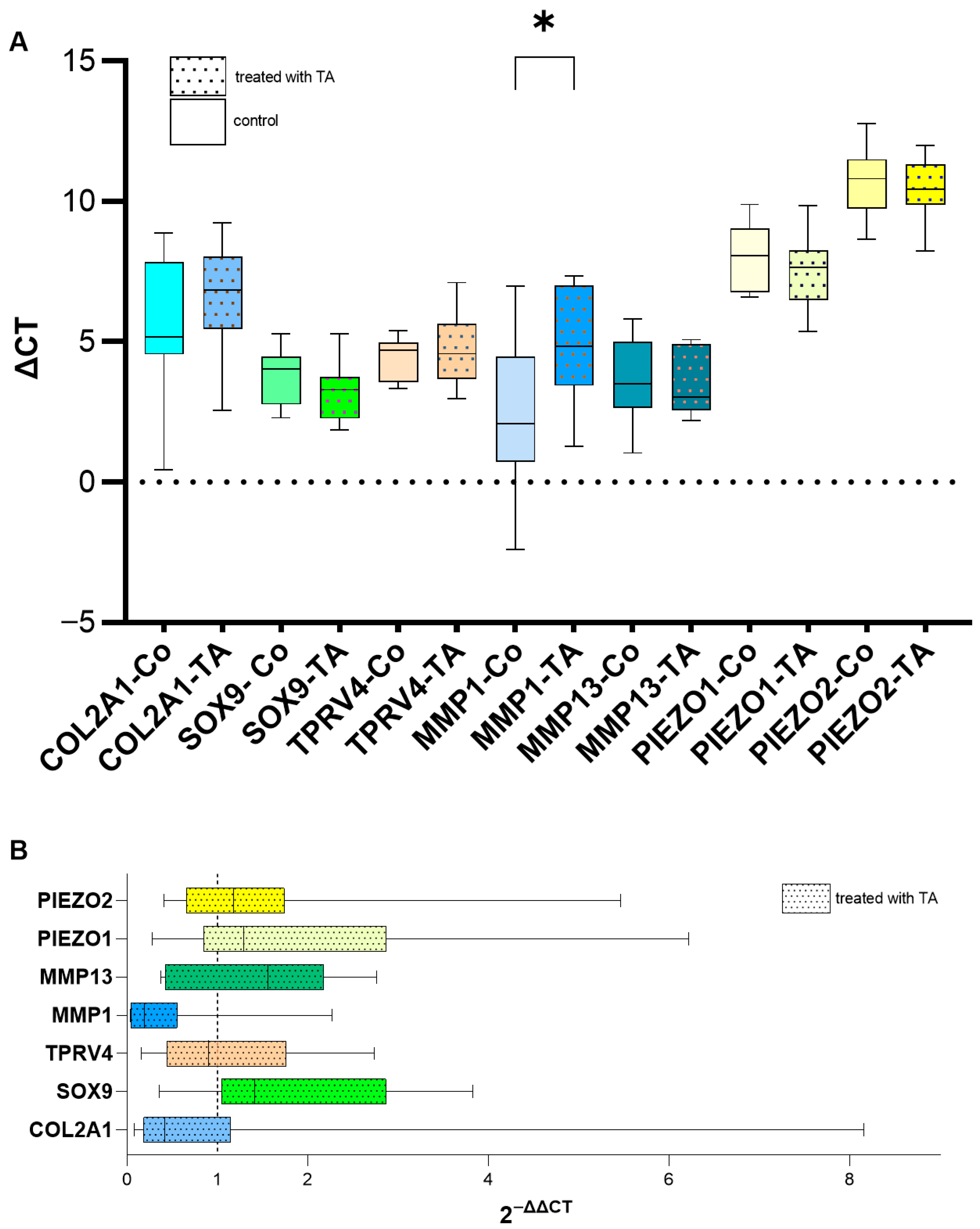

2.5. Effect of TA on the Expression of the Tested Genes in Chondrocytes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Isolation of Primary Chondrocytes

4.2. Determination of the Optimal TA Dosage

4.3. Elasticity Measurements—Atomic Force Microscopy

4.4. Mechanically Induced Intracellular Calcium Dynamics

4.5. Evaluation of Ca2+ Dynamics Under GsMTx4 Treatment

4.6. Gene Expression Analysis via qPCR

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Allen, K.D.; Thoma, L.M.; Golightly, Y.M. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2022, 30, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, J.W.; Schlüter-Brust, K.U.; Eysel, P. The epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2010, 107, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloppenburg, M.; Berenbaum, F. Osteoarthritis year in review 2019: Epidemiology and therapy. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2020, 28, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittenauer, R.; Smith, L.; Aden, K. Background Paper 6.12 Osteoarthritis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner, K.D.; Shrive, N.G.; Frank, C.B. Dexamethasone inhibits inflammation and cartilage damage in a new model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Res. 2014, 32, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, B.L.; Kelmendi-Doko, A.; Balutis, E.C.; Marra, K.G.; Ateshian, G.A.; Hung, C.T. Dexamethasone Release from Within Engineered Cartilage as a Chondroprotective Strategy Against Interleukin-1α. Tissue Eng. Part A 2016, 22, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoo, J.L.; Danial, C.M.; Braun, H.J.; Pouliot, M.A.; Kim, H.J. The chondrotoxicity of single-dose corticosteroids. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2012, 20, 1809–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brew, K.; Nagase, H. The tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs): An ancient family with structural and functional diversity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1803, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, D.W.; Dodge, G.R. Dose-dependent effects of corticosteroids on the expression of matrix-related genes in normal and cytokine-treated articular chondrocytes. Inflamm. Res. 2003, 52, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, C.; Traub, F.; Sachsenmaier, S.; Riester, R.; Mederake, M.; Konrads, C.; Danalache, M. An exploratory study of cell stiffness as a mechanical label-free biomarker across multiple musculoskeletal sarcoma cells. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umrath, F.; Pfeifer, A.; Cen, W.; Danalache, M.; Reinert, S.; Alexander, D.; Naros, A. How osteogenic is dexamethasone?—Effect of the corticosteroid on the osteogenesis, extracellular matrix, and secretion of osteoclastogenic factors of jaw periosteum-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 953516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, G.V.; Schumacher, H.R. Electron microscopic study of depot corticosteroid crystals with clinical studies after intra-articular injection. J. Rheumatol. 1979, 6, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCarty, D.J. Crystals and arthritis. Dis. Mon. 1994, 40, 255–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Perry, L.; Deodhar, A. Intra-articular and soft tissue injections, a systematic review of relative efficacy of various corticosteroids. Clin. Rheumatol. 2014, 33, 1695–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernecke, C.; Braun, H.J.; Dragoo, J.L. The Effect of Intra-articular Corticosteroids on Articular Cartilage: A Systematic Review. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2015, 3, 2325967115581163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentiva. Fachinfo Triam Injekt. Available online: https://www.zentiva.de/-/media/files/zentivade/produkte/triam-40mg-lichtenstein/_de_fi_triam_40mg_lichtenstein.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Suntiparpluacha, M.; Tammachote, N.; Tammachote, R. Triamcinolone acetonide reduces viability, induces oxidative stress, and alters gene expressions of human chondrocytes. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 4985–4992. [Google Scholar]

- Weitoft, T.; Öberg, K. Dosing of intra-articular triamcinolone hexacetonide for knee synovitis in chronic polyarthritis: A randomized controlled study. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2019, 48, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P.J. Glucocorticosteroids: Current and future directions. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Warburton, C.; Perez, O.F.; Wang, Y.; Ho, L.; Finelli, C.; Ehlen, Q.T.; Wu, C.; Rodriguez, C.D.; Kaplan, L.; et al. Hippo-PKCζ-NFκB signaling axis: A druggable modulator of chondrocyte responses to mechanical stress. iScience 2024, 27, 109983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, W.; Wu, A.; Zhang, X.; Tong, W.; Ho, K.K.; Qin, L.; Song, H.; Mak, K.K. Reciprocal inhibition of YAP/TAZ and NF-κB regulates osteoarthritic cartilage degradation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nims, R.; Palmer, D.R.; Kassab, J.; Zhang, B.; Guilak, F. The chondrocyte “mechanome”: Activation of the mechanosensitive ion channels TRPV4 and PIEZO1 drives unique transcriptional signatures. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Nims, R.J.; Savadipour, A.; Zhang, Q.; Leddy, H.A.; Liu, F.; McNulty, A.L.; Chen, Y.; Guilak, F.; Liedtke, W.B. Inflammatory signaling sensitizes Piezo1 mechanotransduction in articular chondrocytes as a pathogenic feed-forward mechanism in osteoarthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2001611118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Leddy, H.A.; Chen, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Zelenski, N.A.; McNulty, A.L.; Wu, J.; Beicker, K.N.; Coles, J.; Zauscher, S.; et al. Synergy between Piezo1 and Piezo2 channels confers high-strain mechanosensitivity to articular cartilage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E5114–E5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Xing, R.; Huang, Z.; Yin, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Ding, L.; Wang, P. Excessive mechanical stress induces chondrocyte apoptosis through TRPV4 in an anterior cruciate ligament-transected rat osteoarthritis model. Life Sci. 2019, 228, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Guan, H.; Wang, H.; Tao, K.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Glucocorticoid counteracts cellular mechanoresponses by LINC01569-dependent glucocorticoid receptor-mediated mRNA decay. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd9923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, C.; Danese, A.; Missiroli, S.; Patergnani, S.; Pinton, P. Calcium Dynamics as a Machine for Decoding Signals. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Chen, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, Q. The potential role of mechanosensitive ion channels in substrate stiffness-regulated Ca2+ response in chondrocytes. Connect. Tissue Res. 2022, 63, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Xiong, Z.; Ke, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, X.; Li, Z. Exploring the Multifactorial Regulation of PIEZO1 in Chondrocytes: Mechanisms and Implications. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 22, 3393–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Hu, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Pang, X.; Wen, C.Y.; Tang, B. Extracellular Calcium Ion Concentration Regulates Chondrocyte Elastic Modulus and Adhesion Behavior. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, T.L.; Wann, A.K.T. Mechanoadaptation: Articular cartilage through thick and thin. J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, D.R.; Beaupré, G.S.; Wong, M.; Smith, R.L.; Andriacchi, T.P.; Schurman, D.J. The mechanobiology of articular cartilage development and degeneration. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2004, 427, S69–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.O.; Nishida, K.; Bavington, C.; Godolphin, J.L.; Dunne, E.; Walmsley, S.; Jobanputra, P.; Nuki, G.; Salter, D.M. Hyperpolarisation of cultured human chondrocytes following cyclical pressure-induced strain: Evidence of a role for alpha 5 beta 1 integrin as a chondrocyte mechanoreceptor. J. Orthop. Res. 1997, 15, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Perera, P.; Liu, J.; Wu, L.C.; Rath, B.; Butterfield, T.A.; Agarwal, S. Transcriptome-wide gene regulation by gentle treadmill walking during the progression of monoiodoacetate-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63, 1613–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanwanseele, B.; Eckstein, F.; Knecht, H.; Stüssi, E.; Spaepen, A. Knee cartilage of spinal cord-injured patients displays progressive thinning in the absence of normal joint loading and movement. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46, 2073–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popma, J.W.; Snel, F.W.; Haagsma, C.J.; Brummelhuis-Visser, P.; Oldenhof, H.G.; van der Palen, J.; van de Laar, M.A. Comparison of 2 Dosages of Intraarticular Triamcinolone for the Treatment of Knee Arthritis: Results of a 12-week Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Rheumatol. 2015, 42, 1865–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pemmari, A.; Leppänen, T.; Hämäläinen, M.; Moilanen, T.; Vuolteenaho, K.; Moilanen, E. Widespread regulation of gene expression by glucocorticoids in chondrocytes from patients with osteoarthritis as determined by RNA-Seq. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2020, 22, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa, F.; Matsuno, H.; Yudoh, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Katayama, R.; Kimura, T. Corticosteroid treatment induces chondrocyte apoptosis in an experimental arthritis model and in chondrocyte cultures. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2002, 20, 773–781. [Google Scholar]

- McAlindon, T.E.; LaValley, M.P.; Harvey, W.F.; Price, L.L.; Driban, J.B.; Zhang, M.; Ward, R.J. Effect of Intra-articular Triamcinolone vs Saline on Knee Cartilage Volume and Pain in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 317, 1967–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Abram, F.; Pelletier, J.P.; Raynauld, J.P.; Dorais, M.; d’Anjou, M.A.; Martel-Pelletier, J. Fully automated system for the quantification of human osteoarthritic knee joint effusion volume using magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2010, 12, R173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, A.; Newcomb, E.; DiStefano, S.; Poplawski, J.; Kim, J.; Axe, M.; Lucas Lu, X. Triamcinolone acetonide has minimal effect on short- and long-term metabolic activities of cartilage. J. Orthop. Res. 2024, 42, 2426–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euppayo, T.; Siengdee, P.; Buddhachat, K.; Pradit, W.; Chomdej, S.; Ongchai, S.; Nganvongpanit, K. In Vitro effects of triamcinolone acetonide and in combination with hyaluronan on canine normal and spontaneous osteoarthritis articular cartilage. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2016, 52, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, A.I.; Richmond, J.C.; Kraus, V.B.; Gomoll, A.; Jones, D.G.; Huffman, K.M.; Peterfy, C.; Cinar, A.; Lufkin, J.; Kelley, S.D. Safety and Efficacy of Repeat Administration of Triamcinolone Acetonide Extended-release in Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Phase 3b, Open-label Study. Rheumatol. Ther. 2019, 6, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, K.M.; Sicard, D.; Tschumperlin, D.J.; Westendorf, J.J. Atomic Force Microscopy Micro-Indentation Methods for Determining the Elastic Modulus of Murine Articular Cartilage. Sensors 2023, 23, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliogeryte, K.; Botto, L.; Lee, D.A.; Knight, M.M. Chondrocyte dedifferentiation increases cell stiffness by strengthening membrane-actin adhesion. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2016, 24, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Zeng, X.; Li, C.; Yin, H.; Mao, S.; Ren, D. Alteration in cartilage matrix stiffness as an indicator and modulator of osteoarthritis. Biosci. Rep. 2024, 44, BSR20231730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danalache, M.; Kleinert, R.; Schneider, J.; Erler, A.L.; Schwitalle, M.; Riester, R.; Traub, F.; Hofmann, U.K. Changes in stiffness and biochemical composition of the pericellular matrix as a function of spatial chondrocyte organisation in osteoarthritic cartilage. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2019, 27, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, E.; Kramer, J.; Rohwedel, J.; Notbohm, H.; Müller, R.; Gutsmann, T.; Rotter, N. Effect of matrix elasticity on the maintenance of the chondrogenic phenotype. Tissue Eng. Part A 2010, 16, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickey, W.R.; Lee, G.M.; Guilak, F. Viscoelastic properties of chondrocytes from normal and osteoarthritic human cartilage. J. Orthop. Res. 2000, 18, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fackler, N.P.; Yareli-Salinas, E.; Callan, K.T.; Athanasiou, K.A.; Wang, D. In Vitro Effects of Triamcinolone and Methylprednisolone on the Viability and Mechanics of Native Articular Cartilage. Am. J. Sports Med. 2023, 51, 2465–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danalache, M.; Jacobi, L.F.; Schwitalle, M.; Hofmann, U.K. Assessment of biomechanical properties of the extracellular and pericellular matrix and their interconnection throughout the course of osteoarthritis. J. Biomech. 2019, 97, 109409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilusz, R.E.; Zauscher, S.; Guilak, F. Micromechanical mapping of early osteoarthritic changes in the pericellular matrix of human articular cartilage. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2013, 21, 1895–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, S.J.; Bonnet, C.S.; Blain, E.J. Mechanical Cues: Bidirectional Reciprocity in the Extracellular Matrix Drives Mechano-Signalling in Articular Cartilage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.; Han, L.; Wang, L.; Lu, X.L. Calcium signaling of in situ chondrocytes in articular cartilage under compressive loading: Roles of calcium sources and cell membrane ion channels. J. Orthop. Res. 2018, 36, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Meng, N.; Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Q. TRPV4 and PIEZO Channels Mediate the Mechanosensing of Chondrocytes to the Biomechanical Microenvironment. Membranes 2022, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savadipour, A.; Nims, R.J.; Rashidi, N.; Garcia-Castorena, J.M.; Tang, R.; Marushack, G.K.; Oswald, S.J.; Liedtke, W.B.; Guilak, F. Membrane stretch as the mechanism of activation of PIEZO1 ion channels in chondrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2221958120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Bai, J.D.; Wu, X.A.; Liu, X.N.; Zhang, M.; Chen, W.Y. Microniche geometry modulates the mechanical properties and calcium signaling of chondrocytes. J. Biomech. 2020, 104, 109729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Ayon, G.M.; Oliver, D.J.; Grutter, P.H.; Komarova, S.V. Deconvolution of calcium fluorescent indicator signal from AFM cantilever reflection. Microsc. Microanal. 2012, 18, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.H.; Lin, Y.H.; Lin, S.; Tsai-Wu, J.J.; Herbert Wu, C.H.; Jiang, C.C. Surface ultrastructure and mechanical property of human chondrocyte revealed by atomic force microscopy. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2008, 16, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasambandam, R.; Ghatak, C.; Yasmann, A.; Nishizawa, K.; Sachs, F.; Ladokhin, A.S.; Sukharev, S.I.; Suchyna, T.M. GsMTx4: Mechanism of Inhibiting Mechanosensitive Ion Channels. Biophys. J. 2017, 112, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.K.; Huntley, J.S.; Bush, P.G.; Simpson, A.H.; Hall, A.C. Chondrocyte death in mechanically injured articular cartilage--the influence of extracellular calcium. J. Orthop. Res. 2009, 27, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Im, G.-I. SOX Trio Decrease in the Articular Cartilage with the Advancement of Osteoarthritis. Connect. Tissue Res. 2011, 52, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Huang, X.; Karperien, M.; Post, J.N. Correlation between Gene Expression and Osteoarthritis Progression in Human. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Ji, Q.; Wang, X.; Kang, L.; Fu, Y.; Yin, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y. SOX9 is a regulator of ADAMTSs-induced cartilage degeneration at the early stage of human osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2015, 23, 2259–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempfer, H.; Gehwolf, R.; Lehner, C.; Wagner, A.; Mtsariashvili, M.; Bauer, H.C.; Resch, H.; Tauber, M. Effects of crystalline glucocorticoid triamcinolone acetonide on cultered human supraspinatus tendon cells. Acta Orthop. 2009, 80, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kypriotou, M.; Fossard-Demoor, M.; Chadjichristos, C.; Ghayor, C.; de Crombrugghe, B.; Pujol, J.P.; Galéra, P. SOX9 exerts a bifunctional effect on type II collagen gene (COL2A1) expression in chondrocytes depending on the differentiation state. DNA Cell Biol. 2003, 22, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Siddiq, A.; Oettinger, C.W.; D’Souza, M.J. Potentiation of pro-inflammatory cytokine suppression and survival by microencapsulated dexamethasone in the treatment of experimental sepsis. J. Drug Target. 2011, 19, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, A.; Das, B. The role of inflammatory mediators and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the progression of osteoarthritis. Biomater. Biosyst. 2024, 13, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rübenhagen, R.; Schüttrumpf, J.P.; Stürmer, K.M.; Frosch, K.-H. Interleukin-7 levels in synovial fluid increase with age and MMP-1 levels decrease with progression of osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop. 2012, 83, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrage, P.S.; Mix, K.S.; Brinckerhoff, C.E. Matrix Metalloproteinases: Role in Arthritis. Front. Biosci. 2006, 11, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefani, R.M.; Lee, A.J.; Tan, A.R.; Halder, S.S.; Hu, Y.; Guo, X.E.; Stoker, A.M.; Ateshian, G.A.; Marra, K.G.; Cook, J.L.; et al. Sustained low-dose dexamethasone delivery via a PLGA microsphere-embedded agarose implant for enhanced osteochondral repair. Acta Biomater. 2020, 102, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilak, F.; Zell, R.A.; Erickson, G.R.; Grande, D.A.; Rubin, C.T.; McLeod, K.J.; Donahue, H.J. Mechanically induced calcium waves in articular chondrocytes are inhibited by gadolinium and amiloride. J. Orthop. Res. 1999, 17, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, W.R.; Rose, B. Calcium in (junctional) intercellular communication and a thought on its behavior in intracellular communication. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1978, 307, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Wang, L.; Umrath, F.; Naros, A.; Reinert, S.; Alexander, D. Three-Dimensionally Cultured Jaw Periosteal Cells Attenuate Macrophage Activation of CD4+ T Cells and Inhibit Osteoclastogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umrath, F.; Thomalla, C.; Pöschel, S.; Schenke-Layland, K.; Reinert, S.; Alexander, D. Comparative Study of MSCA-1 and CD146 Isolated Periosteal Cell Subpopulations. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 51, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liang, C.; Jud, S.; Frantz, S.; Riester, R.; Danalache, M.; Umrath, F. Triamcinolone Modulates Chondrocyte Biomechanics and Calcium-Dependent Mechanosensitivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021055

Liang C, Jud S, Frantz S, Riester R, Danalache M, Umrath F. Triamcinolone Modulates Chondrocyte Biomechanics and Calcium-Dependent Mechanosensitivity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021055

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Chen, Sina Jud, Sandra Frantz, Rosa Riester, Marina Danalache, and Felix Umrath. 2026. "Triamcinolone Modulates Chondrocyte Biomechanics and Calcium-Dependent Mechanosensitivity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021055

APA StyleLiang, C., Jud, S., Frantz, S., Riester, R., Danalache, M., & Umrath, F. (2026). Triamcinolone Modulates Chondrocyte Biomechanics and Calcium-Dependent Mechanosensitivity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021055