Multi-Omics Profiling of the Hepatopancreas of Ridgetail White Prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda Under Sulfate Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. The Variation in pH, Salinity, and Major Ions in Water Bodies with Different Sulfate Concentrations

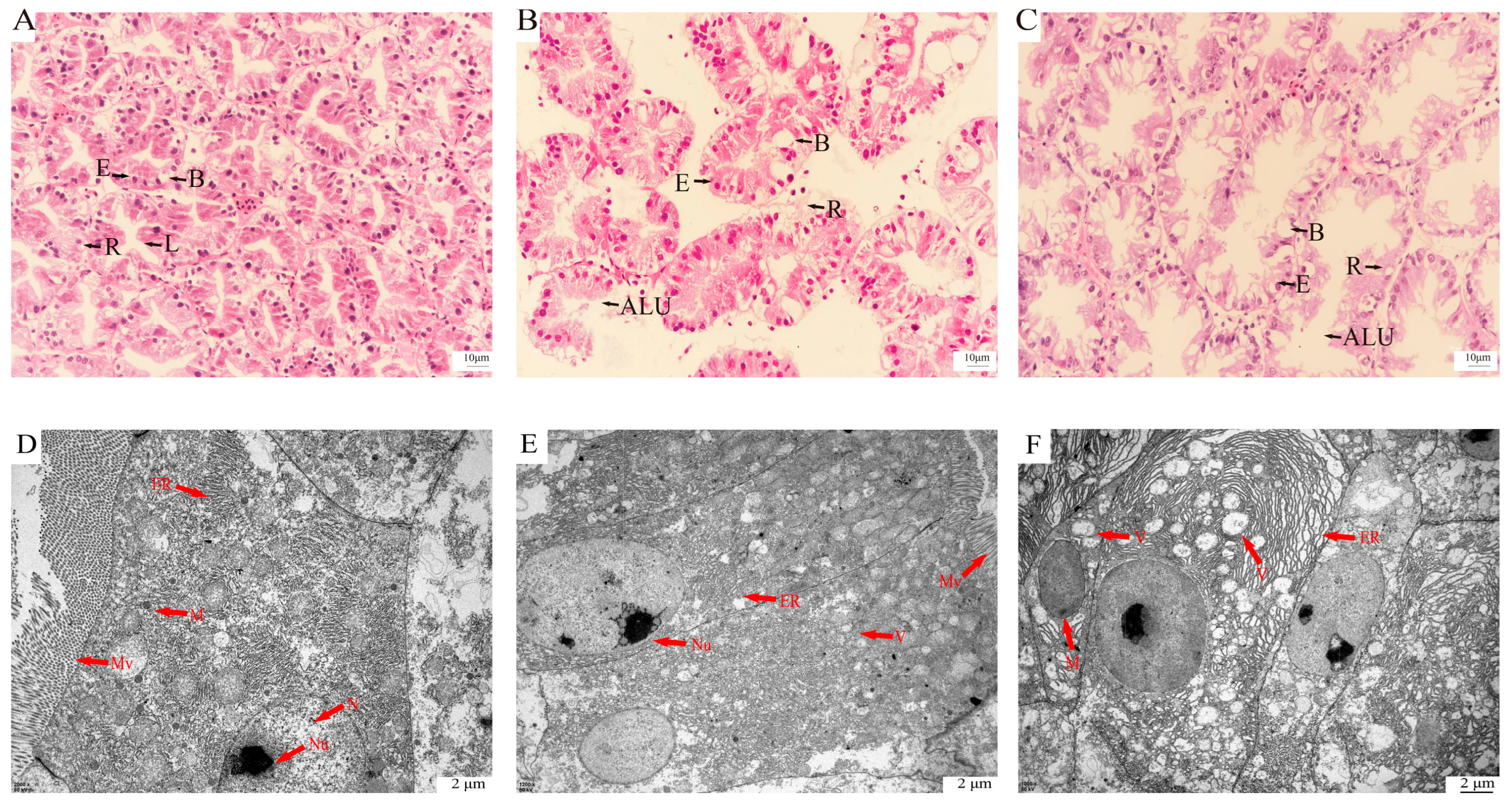

2.2. Histomorphometric Analysis

2.3. Transcriptomic Analysis Under Sulfate Stress

2.4. Proteomic Analysis Under Sulfate Stress

2.5. Integrated Transcriptome–Proteome Analysis

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR) Validation

3. Discussion

3.1. Energy Metabolic Changes Induced by Sulfate Stress

3.2. Antioxidant and Metabolic Defense Responses Induced by Sulfate Stress

3.3. Ionic Homeostasis and Signaling Regulation Responses Induced by Sulfate Stress

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sulfate Stress Experiments and Sampling

4.2. Observation of Tissue and Ultrastructural Changes

4.3. Transcriptomics Analysis

4.4. Proteomic Analysis

4.5. Validation of DEGs by RT-qPCR

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| H.E | hematoxylin–eosin |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| ddH2O | distilled deionized water |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| ALU | abnormal lumen |

| Mv | microvilli |

| Nu | nucleolus |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| DEG/DEGs | differentially expressed gene(s) |

| RT-qPCR | quantitative real-time PCR |

| DEP/DEPs | differentially expressed protein(s) |

| SDS | sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LC50 | median lethal concentration |

| OXPHOS | oxidative phosphorylation |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| NAD+ | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (oxidized form) |

| NADPH/GSH | reducing power: NADPH and glutathione |

| cAMP | cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| NCX | Na+/Ca2+ exchanger |

| HK2 | Hexokinase 2 |

| ENO | Enolase |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| PKM | Pyruvate kinase, muscle |

| ADCY9 | Adenylyl cyclase 9 |

| PGAM2 | Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 |

| GPX | Glutathione peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

References

- Chang, Y.; Liang, L. Advances in research of physiological and molecular mechanisms related to alkali-saline adaptation for fish species inhabiting alkali-saline water. J. Fish. China 2021, 45, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.L.; Lai, Q.F.; Zhou, K.; Rizalita, R.E.; Wang, H. Developmental biology of medaka fish (Oryzias latipes) exposed to alkalinity stress. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2010, 26, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, Q.; Wang, L. Carbonate alkalinity and dietary protein levels affected growth performance, intestinal immune responses and intestinal microflora in Songpu mirror carp (Cyprinus carpio Songpu). Aquaculture 2021, 545, 737135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.X. Soil salinization control and sustainable agriculture in north-west inland region of China. Acta Bot. Boreali-Occident. Sin. 2003, 23, 1063–1068. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Lai, Q.; Yao, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhou, K.; Wang, H. Combined effects of carbonate alkalinity and pH on survival, growth and haemocyte parameters of the Venus clam Cyclina sinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 35, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.R.; Minhas, P.S. Strategies for managing saline/alkali waters for sustainable agricultural production in South Asia. Agric. Water Manag. 2005, 78, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, M.; Li, S.; Wei, X.; Ding, L.; Han, S.; Wang, P.; Lv, B.; Chen, Z.; Sun, Y. Integrated application of multi-omics approach and biochemical assays provides insights into physiological responses to saline-alkaline stress in the gills of crucian carp (Carassius auratus). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, A.; Pati, S.G.; Panda, F.; Mohanty, L.; Paital, B. Low salinity induced challenges in the hardy fish Heteropneustes fossilis; future prospective of aquaculture in near coastal zones. Aquaculture 2021, 543, 737007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, H.; Pan, S.; Yang, X.; Gao, Q.; Dong, S. Rapidly increased greenhouse gas emissions by Pacific white shrimp aquacultural intensification and potential solutions for mitigation in China. Aquaculture 2024, 587, 740825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Singh, P. Global Scenario of Shrimp Industry: Present Status and Future Prospects. In Shrimp Culture Technology: Farming, Health Management and Quality Assurance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal, H. Shrimp farming advances, challenges, and opportunities. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2023, 54, 1092–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Souvi, K.; Sun, C.; Che, B.; Vodounon, A. Shrimp industry in China: Overview of the trends in the production, imports and exports during the last two decades, challenges, and outlook. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 7, 1287034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xie, J.; Shi, H.; Li, C. Hematodinium infections in cultured ridgetail white prawns, Exopalaemon carinicauda, in eastern China. Aquaculture 2010, 300, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Ge, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Li, J. Metabolomic responses based on transcriptome of the hepatopancreas in Exopalaemon carinicauda under carbonate alkalinity stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 268, 115723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Li, J.; Shi, K.; He, Y.; Gao, B.; Liu, P.; Li, J. Estimation of heritability and genetic correlation of saline-alkali tolerance in Exopalaemon carinicauda. Prog. Fish. Sci. 2020, 42, 117–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.Q.; Neori, A.; He, Y.Y.; Li, J.T.; Qiao, L.; Preston, S.I.; Liu, P.; Li, J. Development and current state of seawater shrimp farming, with an emphasis on integrated multi-trophic pond aquaculture farms, in China—A review. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 2544–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ge, Q.; Li, J.; Li, J. Effects of inbreeding on growth and survival rates, and immune responses of ridgetail white prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda against infection by Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Aquaculture 2020, 519, 734755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wei, J.; Liu, C.; Li, F.; Xiang, J. Genome sequences of marine shrimp Exopalaemon carinicauda Holthuis provide insights into genome size evolution of Caridea. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, P.; Liu, P.; Chen, P.; Li, J. The roles of Na+/K+-ATPase alpha-subunit gene from the ridgetail white prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda in response to salinity stresses. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015, 42, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Li, J. Characterization, functional analysis, and expression levels of three carbonic anhydrases in response to pH and saline-alkaline stresses in the ridgetail white prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda. Cell Stress Chaperones 2019, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vera, C.; Brown, J.H. Effects of alkalinity and total hardness on growth and survival of postlarvae freshwater prawns, Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De Man 1879). Aquaculture 2017, 473, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.L.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Zhou, K.; Ying, C.Q.; Lai, Q.F. Transcriptomic profiles of Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) in response to alkalinity stress. Genet. Mol. Res. 2012, 11, 2200–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, K.; Donaghy, L.; Volety, A. Effect of acute salinity changes on hemolymph osmolality and clearance rate of the non-native mussel, Perna viridis, and the native oyster, Crassostrea virginica, in Southwest Florida. Aquat. Invasions 2013, 8, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Guo, W.; Lai, Q.; Shi, J.; Zhou, K.; Qi, H.; Lin, T.; Li, Z.; Wang, H. Gymnocypris przewalskii decreases cytosolic carbonic anhydrase expression to compensate for respiratory alkalosis and osmoregulation in the saline-alkaline lake Qinghai. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2016, 186, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Li, M.; Qin, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Li, J.; Li, J. Mechanism of carbonate alkalinity exposure on juvenile Exopalaemon carinicauda revealed by transcriptome and microRNA analysis. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 816932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Li, W.; Ge, Q.; Qin, Z.; Li, J.; Li, J. Effects of long-term high carbonate alkalinity stress on ovarian development in Exopalaemon carinicauda. Water 2022, 14, 3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Li, J. Effect of high alkalinity on shrimp gills: Histopathological alternations and cell specific responses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 256, 114902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.F.; Xu, Z.H.; Yao, Z.L.; Lai, Q.F. Effects of irrigation on the salt ions in sulfate-type saline-alkali soil. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2019, 33, 118–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainen, J.; Hu, X.; Mäkinen, M.; Karjalainen, A.; Järvistö, J.; Järvenpää, K.; Sepponen, M.; Leppänen, M.T. Sulfate sensitivity of aquatic organism in soft freshwaters explored by toxicity tests and species sensitivity distribution. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 258, 114984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhu, C.; Su, J. Comparative study on growth, hepatopancreas and gill histological structure, and enzyme activities of Litopenaeus vannamei under SO42−/Cl− stress in low saline water. South China Fish. Sci. 2025, 21, 118–126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Nan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Duan, Y. Changes in physiological homeostasis in the gills of Litopenaeus vannamei under carbonate alkalinity stress and recovery conditions. Fishes 2024, 9, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Li, Z.; Ma, B.; Zuo, R.; Shen, X.; Chen, M.; Ren, C.; Zheng, W.; Cai, Z.; Li, J. Effects of carbonate alkalinity on antioxidants, immunity and intestinal flora of Penaeus vannamei. Fishes 2024, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z. Examination of the relationship of carbonate alkalinity stress and ammonia metabolism disorder-mediated apoptosis in the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis: Potential involvement of the ROS/MAPK signaling pathway. Aquaculture 2024, 579, 740179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Li, S.; He, Z.; Ma, Z.; Zhu, C. Effects of sulfate content and salinity on growth, oxygen consumption, Na+/K+-ATPase activity, and hepatopancreas histopathology of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2025, 43, 1350–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Gao, G.; Qin, K.; Jiang, X.; Che, C.; Li, Y.; Mu, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, H. Effects of sulfate on survival, osmoregulation and immune inflammation of mud crab (Scylla paramamosain) under low salt conditions. Aquaculture 2024, 590, 741029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, J. Effects of acute salinity stress on the survival and prophenoloxidase system of Exopalaemon carinicauda. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2020, 39, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Lou, F.; Zhang, Y.; Song, N. Gill transcriptome sequencing and de novo annotation of Acanthogobius ommaturus in response to salinity stress. Genes 2020, 11, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Long, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Han, S.; Yan, S. Integrated transcriptome, proteome and physiology analysis of Epinephelus coioides after exposure to copper nanoparticles or copper sulfate. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-B.; Peng, L.-N.; Yan, X.-H. Multi-omics responses of red algae Pyropia haitanensis to intertidal desiccation during low tides. Algal Res. 2021, 58, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Xie, J.; Huang, M.; Chen, C.; Qian, D.; Qin, J.G.; Chen, L.; Jia, Y.; Li, E. Growth and health responses to long-term pH stress in Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquac. Rep. 2020, 16, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.; Ndandala, C.B.; Lei, Y.; Shija, V.M.; Luo, J.; Wang, P.; Wen, C.; Liang, H. Cadmium-induced oxidative stress, histopathology, and transcriptomic changes in the hepatopancreas of Fenneropenaeus merguiensis. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 36, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.D.; Si, M.R.; Jiang, S.G.; Yang, Q.B.; Jiang, S.; Yang, L.S.; Huang, J.H.; Chen, X.; Zhou, F.L.; Li, E. Transcriptome and molecular regulatory mechanisms analysis of gills in the black tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon under chronic low-salinity stress. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1118341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Shi, X.; Guo, J.; Mao, X.; Fan, B. Acute stress response in the hepatopancreas of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) under high alkalinity. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 35, 101981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chong, J.; Li, D.; Xia, J. Integrated multi-omics reveals the regulatory mechanism underlying the effects of artificial feed and grass feeding on growth and muscle quality of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, W.; Jin, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Han, D.; Liu, H.; Xie, S. Effects of starvation on glucose and lipid metabolism in gibel carp (Carassius auratus gibelio var. CAS III). Aquaculture 2018, 496, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chi, S.; Zhang, S.; Dong, X.; Yang, Q.; Liu, H.; Tan, B.; Xie, S. Effect of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae meal on lipid and glucose metabolism of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1674–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, F. Comparative transcriptomic analysis unveils a network of energy reallocation in Litopenaeus vannamei responsive to heat-stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 238, 113600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Armenta, C.; Reyes-Zamora, O.; De la Re-Vega, E.; Sanchez-Paz, A.; Mendoza-Cano, F.; Mendez-Romero, O.; Gonzalez-Rios, H.; Muhlia-Almazan, A. Adaptive mitochondrial response of the whiteleg shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei to environmental challenges and pathogens. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2021, 191, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Cruz, O.; Garcia-Carreno, F.; Robles-Romo, A.; Varela-Romero, A.; Muhlia-Almazan, A. Catalytic subunits atpα and atpβ from the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei FOF1 ATP-synthase complex: cDNA sequences, phylogenies, and mRNA quantification during hypoxia. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2011, 43, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Cruz, O.; Calderon de la Barca, A.M.; Uribe-Carvajal, S.; Muhlia-Almazan, A. The function of mitochondrial FOF1 ATP-synthase from the whiteleg shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei muscle during hypoxia. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012, 162, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipovic, D.; Peric, I.; Costina, V.; Stanisavljevic, A.; Gass, P.; Findeisen, P. Social isolation stress-resilient rats reveal energy shift from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation in hippocampal nonsynaptic mitochondria. Life Sci. 2020, 254, 117790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Jiang, J.-J.; Liu, X.; Lu, X.; Liu, Q.-N.; Cheng, Y.-X.; Tang, B.-P.; Dai, L.-S. Differentially expressed genes in immune pathways following Vibrio parahaemolyticus challenge: A study on red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii). Aquac. Rep. 2024, 36, 102047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.R.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.N.; Tang, B.P. Transcriptome analysis reveals immune and antioxidant defense mechanisms in Eriocheir japonica sinensis after ammonia exposure. Animals 2024, 14, 2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paital, B.; Chainy, G. Effects of salinity on O2 consumption, ROS generation and oxidative stress status of gill mitochondria of the mud crab Scylla serrata. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2012, 155, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, C.; Shi, W.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Wan, X. Effects of sulfate stress on tissue damage and physiological function of Litopenaeus vannamei. J. Fish. Sci. China 2024, 31, 910–925. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lu, X.; Jiang, M.; Wu, F.; Tian, J.; Yu, L.; Wen, H. Effects of dietary niacin on liver health in genetically improved farmed tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquac. Rep. 2020, 16, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regoli, F.; Giuliani, M.E. Oxidative pathways of chemical toxicity and oxidative stress biomarkers in marine organisms. Mar. Environ. Res. 2014, 93, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Regenstein, J.M.; Xie, D.; Lu, W.; Ren, X.; Yuan, J.; Mao, L. The oxidative stress and antioxidant responses of Litopenaeus vannamei to low temperature and air exposure. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 72, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Liu, R.; Zhao, K.; Zhong, J. Vital role of SHMT2 in diverse disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 671, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Dong, X.; Tan, B.; Zhang, S.; Chi, S.; Yang, Q.; Liu, H.; Xie, S.; Deng, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. Antioxidant capacity, histology, nutrient composition, and transcriptome of muscle in juvenile hybrid grouper (♀ Epinephelus fuscoguttatus × ♂ Epinephelus lanceolatus) fed oxidized fish oil. Aquaculture 2022, 547, 737510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Zou, Z.; Liu, S.; Lin, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase gene expression during gonad development and its response to LPS and H2O2 challenge in Scylla paramamosain. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2012, 33, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ji, P.; Li, Z.; Sun, Z.; Tran, N.T.; Li, S. Catalase regulates the homeostasis of hemolymph microbiota and autophagy of hemocytes in mud crab (Scylla paramamosain). Aquac. Rep. 2022, 25, 101237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, E.; Kim, H.; Yoon, H. ER Stress-Mediated Signaling: Action Potential and Ca2+ as Key Players. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Peng, Y.; Li, R.; Ji, Z.; Bekaert, M.; Mu, C.; Migaud, H.; Song, W.; Shi, C.; Wang, C. Effects of long-term low salinity on haemolymph osmolality, gill structure and transcriptome in mud crab (Scylla paramamosain). Aquac. Rep. 2024, 38, 102295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Y.; Shen, M.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z. Transcriptome Analysis of Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) Under Prolonged High-Salinity Stress. J. Ocean Univ. China 2021, 21, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, A.E.; Tumbokon, B.L.M. Hepatopancreatic transcriptome response of Penaeus vannamei to dietary ulvan. Isr. J. Aquac.–Bamidgeh 2022, 74, 55685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canosa, L.F.; Bertucci, J.I. The effect of environmental stressors on growth in fish and its endocrine control. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1109461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glombitza, C.; Stockhecke, M.; Schubert, C.J.; Vetter, A.; Kallmeyer, J. Sulfate reduction controlled by organic matter availability in deep sediment cores from the saline, alkaline Lake Van (Eastern Anatolia, Turkey). Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valiente, N.; Menchen, A.; Carrey, R.; Otero, N.; Soler, A.; Sanz, D.; Gomez-Alday, J. Sulfur recycling processes in a eutrophic hypersaline system: Pétrola Lake (SE, Spain). Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2017, 17, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 35892–2018; Laboratory Animal—Guideline for Ethical Review of Animal Welfare. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Li, Q. Sodium sulfate precipitation titration for indirect determination of sulfate in brine. China Well Rock Salt 1994, 3, 37–38. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, D.; Eissler, Y.; Espinoza, J.C.; Kuznar, J. Inter-laboratory ring trial to evaluate real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction methods used for detection of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus in Chile. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 28, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | NCBI Accession Number | Forward Primer (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer (5′-3′) | Amplification Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18S rRNA | GQ369794.1 | GCTATGCGAGCAGGTTTC | CATGGCGTGACAGTTTCC | 98.06% |

| ADH5 | XM_068390262.1 | GGTTCCACCTGTGCTGTC | TGCTCGTTCGGGTTGTAG | 94.19% |

| 4cl3 | XM_068390317.1 | GGAATGACGGAAGTGTTA | GTGAGTTGGAGGAAGGTC | 108.53% |

| TUBA1A | XM_068346384.1 | GCCGCAGGAACTTAGACAT | GGGCATAGGTAACGAGGG | 100.72% |

| Mtarc2 | XM_068390020.1 | GGCGACTCCACATTACCT | GCTCGATCCGTCTTCTTAT | 95.27% |

| Bco1 | XM_068370955.1 | ACGAATAAACCACCCGTCAA | CTCCGTTCCACTCAAATCCA | 92.88% |

| YMR099C | XM_068383251.1 | CGACGAGTGTTGTGGTTC | GGTATTCCTCCTCTTATGG | 109.52% |

| Arsb | XM_068353702.1 | GCAACAATGAAGACCCAG | AAAGCCAAATACAGGAACA | 97.66% |

| Slc31a1 | XM_068387454.1 | TGGAGGGAAGACCTGATG | CGAACAAGAAGTAACCGAGT | 95.32% |

| Ctsc | XM_068372694.1 | ATACCTTGGGCGAGATTG | TCGTGAGACCACCCGTTC | 98.18% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, R.; Gu, C.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Sun, R.; Fu, K.; Shi, W.; Wan, X. Multi-Omics Profiling of the Hepatopancreas of Ridgetail White Prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda Under Sulfate Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021056

Wang R, Gu C, Li H, Wang L, Sun R, Fu K, Shi W, Wan X. Multi-Omics Profiling of the Hepatopancreas of Ridgetail White Prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda Under Sulfate Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021056

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ruixuan, Chen Gu, Hui Li, Libao Wang, Ruijian Sun, Kuipeng Fu, Wenjun Shi, and Xihe Wan. 2026. "Multi-Omics Profiling of the Hepatopancreas of Ridgetail White Prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda Under Sulfate Stress" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021056

APA StyleWang, R., Gu, C., Li, H., Wang, L., Sun, R., Fu, K., Shi, W., & Wan, X. (2026). Multi-Omics Profiling of the Hepatopancreas of Ridgetail White Prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda Under Sulfate Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021056