Integrated Transcriptomic and Machine Learning Analysis Reveals Immune-Related Regulatory Networks in Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Dysregulated Transcriptomic Profiles in Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis

2.2. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis Reveals Disease-Associated Modules

2.3. Functional Enrichment Analysis Highlights Immune and Neural Pathways

2.4. mRNA-miRNA-lncRNA Regulatory Network Analysis

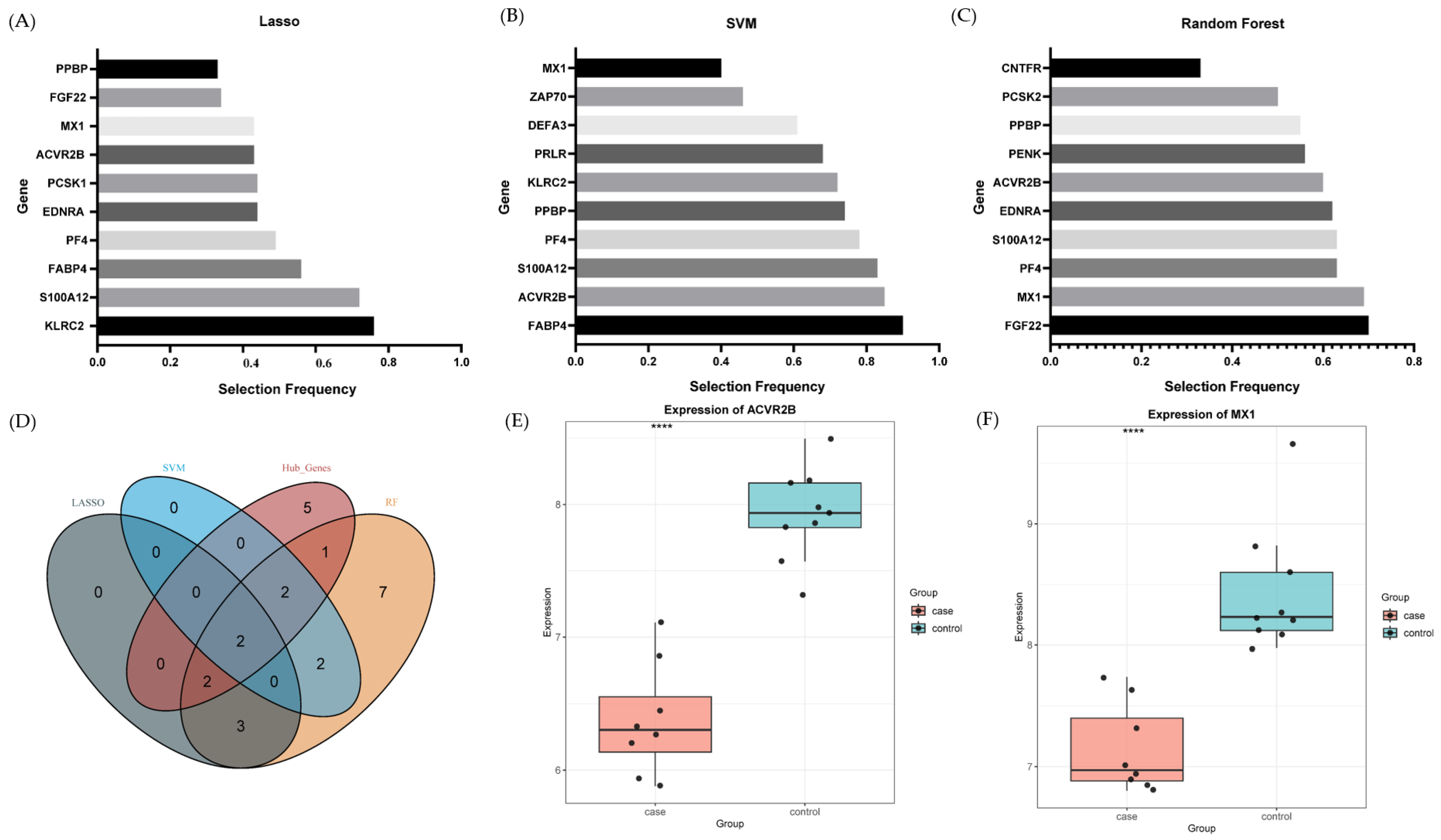

2.5. Machine Learning-Prioritized Features

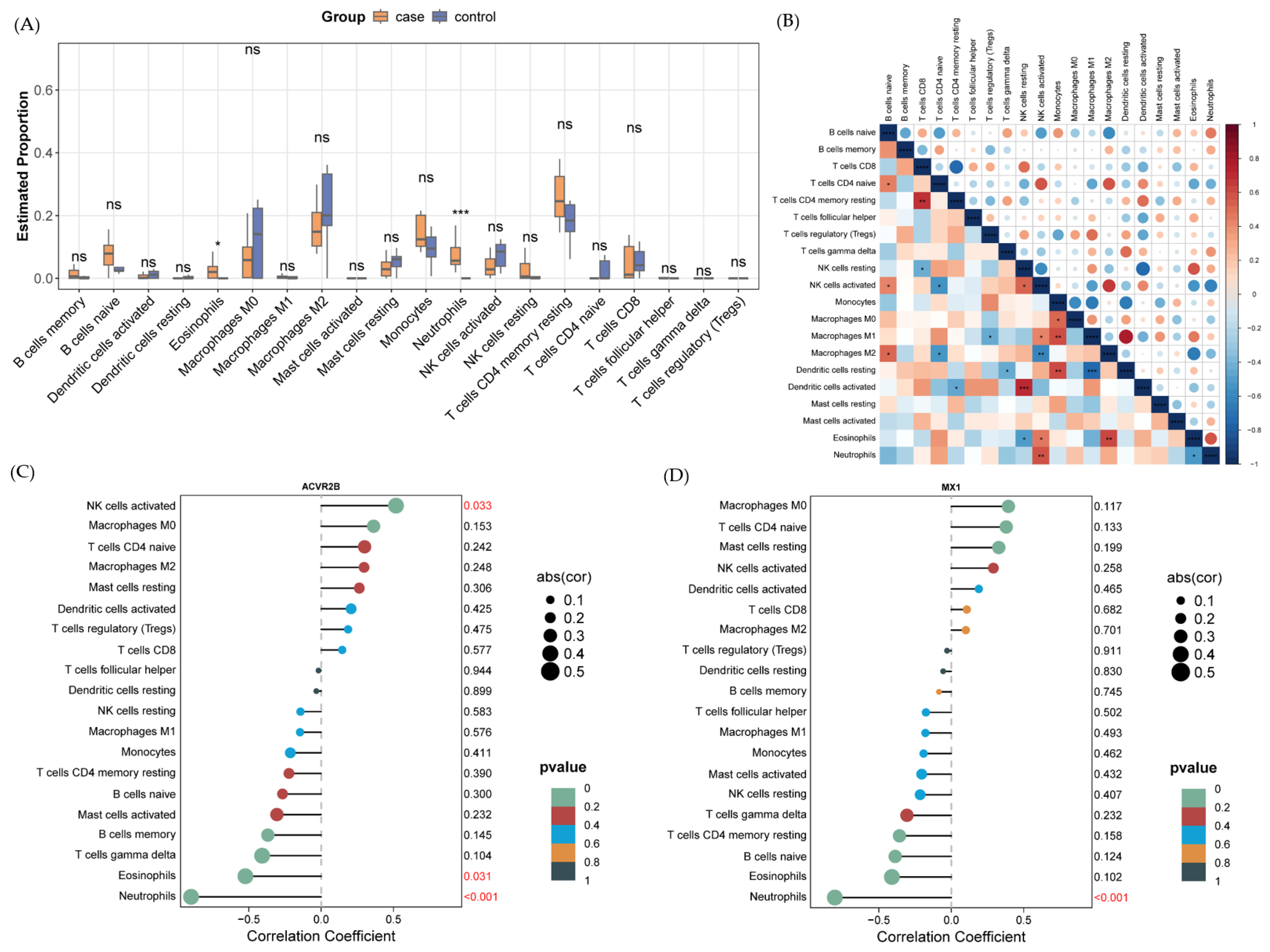

2.6. Immune Cell Infiltration Analysis Uncovers Microenvironmental Alterations

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Acquistion and Preprocessing

4.2. Differential Expression Analysis

4.3. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

4.4. Identification of Immune-Related Hub Genes and Functional Enrichment Analysis

4.5. Construction of the mRNA-miRNA-lncRNA Regulatory Network

4.6. Machine Learning-Based Feature Selection

4.7. Immune Cell Infiltration Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACVR2B | Activin A receptor type 2B |

| Anti-NMDAR | Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor |

| CIBERSORT | Cell-type Identification By Estimating Relative Subsets Of RNA Transcripts |

| ceRNA | Competitive Endogenous RNA |

| DEG | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| FC | Fold Change |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| GEO | Geno Ontology |

| JAK-STAT | Janus Kinase–Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MX1 | Myxovirus resistance protein 1 |

| PI3K-Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase–protein kinase B signaling pathway |

| WGCNA | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis |

References

- Al-Diwani, A.; Handel, A.; Townsend, L.; Pollak, T.; Leite, M.I.; Harrison, P.J.; Lennox, B.R.; Okai, D.; Manohar, S.G.; Irani, S.R. The Psychopathology of NMDAR-Antibody Encephalitis in Adults: A Systematic Review and Phenotypic Analysis of Individual Patient Data. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titulaer, M.J.; McCracken, L.; Gabilondo, I.; Armangué, T.; Glaser, C.; Iizuka, T.; Honig, L.S.; Benseler, S.M.; Kawachi, I.; Martinez-Hernandez, E.; et al. Treatment and Prognostic Factors for Long-Term Outcome in Patients with Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis: An Observational Cohort Study. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnon, I.; Hélie, P.; Bardou, I.; Regnauld, C.; Lesec, L.; Leprince, J.; Naveau, M.; Delaunay, B.; Toutirais, O.; Lemauff, B.; et al. Autoimmune Encephalitis Mediated by B-Cell Response against N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptor. Brain J. Neurol. 2020, 143, 2957–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, N.; Lin, X.; Di, Q. Differential Diagnosis of Autoimmune Encephalitis from Infectious Lymphocytic Encephalitis by Analysing the Lymphocyte Subsets of Cerebrospinal Fluid. Anal. Cell. Pathol. 2019, 2019, 9684175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lian, Y.; Cheng, X. The Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratios Are Independently Associated with the Severity of Autoimmune Encephalitis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 911779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, B.; Liu, X.-N.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Quan, C.; Chen, X.-J. Raised Cerebrospinal Fluid BAFF and APRIL Levels in Anti-N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis: Correlation with Clinical Outcome. J. Neuroimmunol. 2017, 305, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yan, H.; Wang, B.; Wan, J.; Wang, H.; Xia, Y.; Liu, Y.U.; Wang, X.; Wu, H.; Jiang, J.; et al. The Anti-NMDAR1 Antibodies and IL-17 Signaling Pathway Shape NMDAR Encephalitis. Mol. Psychiatry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Z.; Peng, D.; Ren, W.; Tang, Z.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Shu, Y. Immunoregulatory Programs in Anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis Identified by Single-Cell Multi-Omics Analysis. Clin. Transl. Med. 2025, 15, e70173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmena, L.; Poliseno, L.; Tay, Y.; Kats, L.; Pandolfi, P.P. A ceRNA Hypothesis: The Rosetta Stone of a Hidden RNA Language? Cell 2011, 146, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagakis, E.; Bertsias, G.; Verginis, P.; Nakou, M.; Hatziapostolou, M.; Kritikos, H.; Iliopoulos, D.; Boumpas, D.T. Identification of Novel microRNA Signatures Linked to Human Lupus Disease Activity and Pathogenesis: miR-21 Regulates Aberrant T Cell Responses through Regulation of PDCD4 Expression. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ye, Y.; Niu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; You, X.; Chen, H.; Zhao, L.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, F.; et al. Defective PTEN Regulation Contributes to B Cell Hyperresponsiveness in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 246ra99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, G.; Wei, C.; Gao, C.; Hao, J. Linc-MAF-4 Regulates Th1/Th2 Differentiation and Is Associated with the Pathogenesis of Multiple Sclerosis by Targeting MAF. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2017, 31, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, T.; Li, T.; Liang, Z.; Luo, X. LncRNA DLX6-AS1 Promotes Microglial Inflammatory Response in Parkinson’s Disease by Regulating the miR-223-3p/NRP1 Axis. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 431, 113923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Guo, S.; Meng, Z.; Ren, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wang, M. Cytokine/Chemokine Levels in the CSF and Serum of Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1064007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, J.; Tüzün, E.; Wu, H.; Masjuan, J.; Rossi, J.E.; Voloschin, A.; Baehring, J.M.; Shimazaki, H.; Koide, R.; King, D.; et al. Paraneoplastic Anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis Associated with Ovarian Teratoma. Ann. Neurol. 2007, 61, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitaliani, R.; Mason, W.; Ances, B.; Zwerdling, T.; Jiang, Z.; Dalmau, J. Paraneoplastic Encephalitis, Psychiatric Symptoms, and Hypoventilation in Ovarian Teratoma. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 58, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Usatorre, A.; Ciarloni, L.; Angelino, P.; Wosika, V.; Conforte, A.J.; Fonseca Costa, S.S.; Durandau, E.; Monnier-Benoit, S.; Satizabal, H.F.; Despraz, J.; et al. Human Blood Cell Transcriptomics Unveils Dynamic Systemic Immune Modulation along Colorectal Cancer Progression. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e009888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gibson, S.A.; Benveniste, E.N.; Qin, H. Opportunities for Translation from the Bench: Therapeutic Intervention of the JAK/STAT Pathway in Neuroinflammatory Diseases. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 35, 505–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, J.J.; Schwartz, D.M.; Villarino, A.V.; Gadina, M.; McInnes, I.B.; Laurence, A. The JAK-STAT Pathway: Impact on Human Disease and Therapeutic Intervention. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015, 66, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Bougoin, S.; Feferman, T.; Frenkian, M.; Bismuth, J.; Mouly, V.; Clairac, G.; Tzartos, S.; Fadel, E.; Eymard, B.; et al. IL-6 and Akt Are Involved in Muscular Pathogenesis in Myasthenia Gravis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2015, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, R.; Bakay, M.; Hakonarson, H. SOCS-JAK-STAT Inhibitors and SOCS Mimetics as Treatment Options for Autoimmune Uveitis, Psoriasis, Lupus, and Autoimmune Encephalitis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1271102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, O.; Staeheli, P.; Kochs, G. Interferon-Induced Mx Proteins in Antiviral Host Defense. Biochimie 2007, 89, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Masri, A.N.; Heidenreich, F.; Walter, G.F. Interferon-induced Mx Proteins in Brain Tissue of Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Eur. J. Neurol. 2009, 16, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrnes, S.J.; Jamal Eddine, J.; Zhou, J.; Chalmers, E.; Wanicek, E.; Osman, N.; Jenkins, T.A.; Roche, M.; Brew, B.J.; Estes, J.D.; et al. Neuroinflammation Associated with Proviral DNA Persists in the Brain of Virally Suppressed People with HIV. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1570692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abboud, H.; Probasco, J.C.; Irani, S.; Ances, B.; Benavides, D.R.; Bradshaw, M.; Christo, P.P.; Dale, R.C.; Fernandez-Fournier, M.; Flanagan, E.P.; et al. Autoimmune Encephalitis: Proposed Best Practice Recommendations for Diagnosis and Acute Management. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2021, 92, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillenburg, A.; Ireland, G.; Holloway, R.K.; Davies, C.L.; Evans, F.L.; Swire, M.; Bechler, M.E.; Soong, D.; Yuen, T.J.; Su, G.H.; et al. Activin Receptors Regulate the Oligodendrocyte Lineage in Health and Disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 135, 887–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorcet, G.; Benaiteau, M.; Bost, C.; Mengelle, C.; Bonneville, F.; Martin-Blondel, G.; Pariente, J. Two Cases of Late-Onset Anti-NMDAr Auto-Immune Encephalitis after Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Encephalitis. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søgaard, A.; Poulsen, C.A.; Belhouche, N.Z.; Thybo, A.; Hovet, S.T.F.; Larsen, L.; Nilsson, C.; Blaabjerg, M.; Nissen, M.S. Post-Herpetic Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis in Denmark: Current Status and Future Challenges. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandweiss, A.J.; Erickson, T.A.; Jiang, Y.; Kannan, V.; Yarimi, J.M.; Levine, J.M.; Fisher, K.; Muscal, E.; Demmler-Harrison, G.; Murray, K.O.; et al. Infectious Profiles in Pediatric Anti-N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2023, 381, 578139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Cui, X.; Wang, C.; Zong, S.; Wang, L.; Lu, Z. MicroRNA-22-3p Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease by Targeting SOX9 through the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in the Hippocampus. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida Silva, L.F.; Reschke, C.R.; Nguyen, N.T.; Langa, E.; Sanz-Rodriguez, A.; Gerbatin, R.R.; Temp, F.R.; de Freitas, M.L.; Conroy, R.M.; Brennan, G.P.; et al. Genetic Deletion of microRNA-22 Blunts the Inflammatory Transcriptional Response to Status Epilepticus and Exacerbates Epilepsy in Mice. Mol. Brain 2020, 13, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fousert, E.; Toes, R.; Desai, J. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) Take the Central Stage in Driving Autoimmune Responses. Cells 2020, 9, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandpur, R.; Carmona-Rivera, C.; Vivekanandan-Giri, A.; Gizinski, A.; Yalavarthi, S.; Knight, J.S.; Friday, S.; Li, S.; Patel, R.M.; Subramanian, V.; et al. NETs Are a Source of Citrullinated Autoantigens and Stimulate Inflammatory Responses in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 178ra40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankish, A.; Diekhans, M.; Ferreira, A.-M.; Johnson, R.; Jungreis, I.; Loveland, J.; Mudge, J.M.; Sisu, C.; Wright, J.; Armstrong, J.; et al. GENCODE Reference Annotation for the Human and Mouse Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D766–D773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Dunn, P.; Thomas, C.G.; Smith, B.; Schaefer, H.; Chen, J.; Hu, Z.; Zalocusky, K.A.; Shankar, R.D.; Shen-Orr, S.S.; et al. ImmPort, toward Repurposing of Open Access Immunological Assay Data for Translational and Clinical Research. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; SpringerLink: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R Package for Weighted Correlation Network Analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes among Gene Clusters. Omics J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-H.; Liu, S.; Zhou, H.; Qu, L.-H.; Yang, J.-H. starBase v2.0: Decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and Protein–RNA Interaction Networks from Large-Scale CLIP-Seq Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D92–D97. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/nar/article/42/D1/D92/1063720?login=false (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the Lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.M.; Liu, C.L.; Green, M.R.; Gentles, A.J.; Feng, W.; Xu, Y.; Hoang, C.D.; Diehn, M.; Alizadeh, A.A. Robust Enumeration of Cell Subsets from Tissue Expression Profiles. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dataset ID | Sample Type | Disease | RNA Type | Sample Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE277739 | Ovarian teratoma tissue | Anti-NMDAR encephalitis | mRNA | 3 anti-NMDAR encephalitis associated teratoma, 4 non-anti-NMDAR-E teratomas |

| GSE305025 | Peripheral blood | Anti-NMDAR encephalitis | mRNA, lncRNA | 5 anti-NMDAR encephalitis patients, 5 healthy controls |

| GSE287388 | Peripheral blood | Anti-NMDAR encephalitis | miRNA | 9 anti-NMDAR encephalitis patients, 8 healthy controls |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fang, K.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Integrated Transcriptomic and Machine Learning Analysis Reveals Immune-Related Regulatory Networks in Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021044

Fang K, Li X, Wang J. Integrated Transcriptomic and Machine Learning Analysis Reveals Immune-Related Regulatory Networks in Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021044

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Kechi, Xinming Li, and Jing Wang. 2026. "Integrated Transcriptomic and Machine Learning Analysis Reveals Immune-Related Regulatory Networks in Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021044

APA StyleFang, K., Li, X., & Wang, J. (2026). Integrated Transcriptomic and Machine Learning Analysis Reveals Immune-Related Regulatory Networks in Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021044