MDM2 in Tumor Biology and Cancer Therapy: A Review of Current Clinical Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Biological Role of MDM2

2.1. p53-Mediated Oncogenic Regulation

2.2. p53-Independent Functions

- Ubiquitin-dependent degradation (observed upon MDM2 overexpression).

- Ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation. In this pathway, MDM2 enhances the interaction between Rb and the C8 subunit of the 20S proteasome.

2.3. Regulation of MDM2 Activity

2.4. Implications in Tumor Biology of Specific Cancer Histotypes

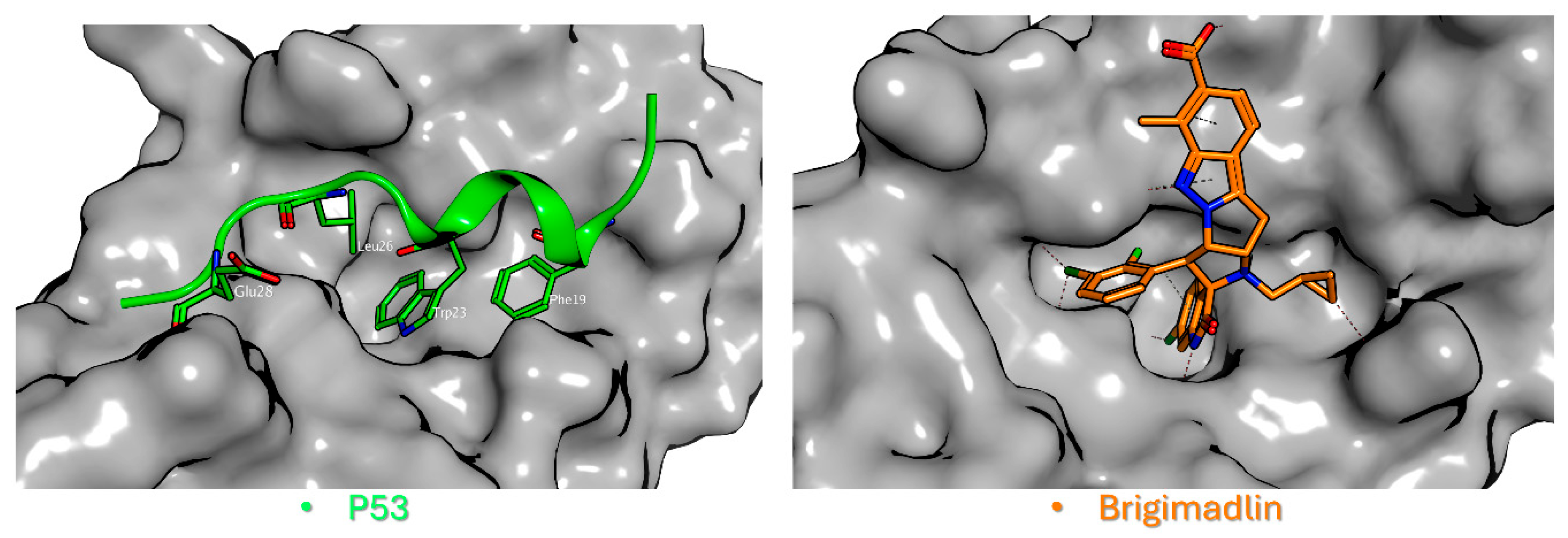

2.5. MDM2 Inhibitors

2.5.1. Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Development

2.5.2. Comparative Analysis of MDM2 Inhibitors: Dosing, Toxicity, and Efficacy

2.6. Combination Strategies and Novel Approaches

2.6.1. Combination Strategies

Chemotherapy

Immunotherapy

Dual MDM2/MDMX Inhibitors

PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras)

Chimeric Antigen Receptor T

MAPK Pathway Cross-Talk

2.6.2. Novel Approaches: Ongoing Clinical Trials of MDM2 Inhibitors

Siremadlin (HDM201)

Alrizomadlin (APG-115)

Milademetan (DS-3032b)

Idasanutlin + Venetoclax

2.7. Clinical Implications of MDM2 Inhibition

2.7.1. Acute Myeloid Leukemia

2.7.2. Dedifferentiated Liposarcoma (DDLPS)

2.7.3. Urothelial Carcinoma (UC)

2.7.4. Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

2.7.5. Melanoma and Regional Chemotherapy Resistance

2.7.6. Glioblastoma

2.7.7. Breast Cancer

2.8. Future Perspectives

3. Conclusions

- -

- Cell cycle arrest and apoptosis: Activated p53 induces p21 and PUMA expression, halting progenitor proliferation.

- -

- Specific defect in megakaryopoiesis: As noted in the Alrizomadlin and Milademetan studies, thrombocytopenia is a major challenge because p53 activation specifically inhibits megakaryocyte differentiation and survival.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BTC | Biliary tract cancer |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| DDLPS | Differentiated Liposarcoma |

| ICIs | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors |

| ILP | Isolated Limb Perfusion |

| MDM2 | Murine Double Minute 2 |

| NSCLC | Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer |

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| PPI | Protein–Protein Interaction |

| PROTACs | Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras |

| RITA | Reactivation of p53 and Induction of Tumor cell Apoptosis |

| UC | Urothelial Carcinoma |

References

- Wade, M.; Li, Y.C.; Wahl, G.M. MDM2, MDMX and p53 in oncogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momand, J.; Jung, D.; Wilczynski, S.; Niland, J. The MDM2 gene amplification database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 3453–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Ross, J.S.; Gay, L.; Dayyani, F.; Roszik, J.; Subbiah, V.; Kurzrock, R. Analysis of MDM2 Amplification: Next-Generation Sequencing of Patients with Diverse Malignancies. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2018, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Aguilar, A.; Bernard, D.; Yang, C.Y. Targeting the MDM2-p53 Protein-Protein Interaction for New Cancer Therapy: Progress and Challenges. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017, 7, a026245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöffski, P.; Lahmar, M.; Lucarelli, A.; Maki, R.G. Brightline-1: Phase II/III trial of the MDM2-p53 antagonist BI 907828 versus doxorubicin in patients with advanced DDLPS. Future Oncol. 2023, 19, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, L.T.; Vu, B.T.; Graves, B.; Carvajal, D.; Podlaski, F.; Filipovic, Z.; Kong, N.; Kammlott, U.; Lukacs, C.; Klein, C.; et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science 2004, 303, 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alt, J.R.; Bouska, A.; Fernandez, M.R.; Cerny, R.L.; Xiao, H.; Eischen, C.M. Mdm2 binds to Nbs1 at sites of DNA damage and regulates double strand break repair. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 18771–18781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, V.; Huang, C.; Zhang, J.; Jia, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Miyagishi, M.; Wu, S. Synergistic cooperation of MDM2 and E2F1 contributes to TAp73 transcriptional activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 449, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udayakumar, T.; Shareef, M.M.; Diaz, D.A.; Ahmed, M.M.; Pollack, A. The E2F1/Rb and p53/MDM2 pathways in DNA repair and apoptosis: Understanding the crosstalk to develop novel strategies for prostate cancer radiotherapy. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2010, 20, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, J.J. The Mdm2-p53 relationship evolves: Mdm2 swings both ways as an oncogene and a tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 1580–1589, Erratum in Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maietta, I.; Viscusi, E.; Laudati, S.; Iannaci, G.; D’Antonio, A.; Melillo, R.M.; Motti, M.L.; De Falco, V. Targeting the p90RSK/MDM2/p53 Pathway Is Effective in Blocking Tumors with Oncogenic Up-Regulation of the MAPK Pathway Such as Melanoma and Lung Cancer. Cells 2024, 13, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stott, F.J.; Bates, S.; James, M.C.; McConnell, B.B.; Starborg, M.; Brookes, S.; Palmero, I.; Ryan, K.; Hara, E.; Vousden, K.H.; et al. The alternative product from the human CDKN2A locus, p14(ARF), participates in a regulatory feedback loop with p53 and MDM2. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 5001–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, C.P.; Weber, J.D. It’s Getting Complicated-A Fresh Look at p53-MDM2-ARF Triangle in Tumorigenesis and Cancer Therapy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 818744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliner, J.D.; Kinzler, K.W.; Meltzer, P.S.; George, D.L.; Vogelstein, B. Amplification of a gene encoding a p53-associated protein in human sarcomas. Nature 1992, 358, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; Lain, S.; Verma, C.S.; Fersht, A.R.; Lane, D.P. Awakening guardian angels: Drugging the p53 pathway. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray-Coquard, I.; Blay, J.Y.; Italiano, A.; Le Cesne, A.; Penel, N.; Zhi, J.; Heil, F.; Rueger, R.; Graves, B.; Ding, M.; et al. Effect of the MDM2 antagonist RG7112 on the P53 pathway in patients with MDM2-amplified, well-differentiated or dedifferentiated liposarcoma: An exploratory proof-of-mechanism study. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangary, S.; Wang, S. Targeting the MDM2-p53 interaction for cancer therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 5318–5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kussie, P.H.; Gorina, S.; Marechal, V.; Elenbaas, B.; Moreau, J.; Levine, A.J.; Pavletich, N.P. Structure of the MDM2 oncoprotein bound to the p53 tumor suppressor transactivation domain. Science 1996, 274, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tovar, C.; Rosinski, J.; Filipovic, Z.; Higgins, B.; Kolinsky, K.; Hilton, H.; Zhao, X.; Vu, B.T.; Qing, W.; Packman, K.; et al. Small-molecule MDM2 antagonists reveal aberrant p53 signaling in cancer: Implications for therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 1888–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos, P.; Beckermann, B.M.; Catalani, O.; Esteve, J.; Gamel, K.; Konopleva, M.Y.; Martinelli, G.; Monnet, A.; Papayannidis, C.; Park, A.; et al. MIRROS: A randomized, placebo-controlled, Phase III trial of cytarabine ± idasanutlin in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Future Oncol. 2020, 16, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopleva, M.Y.; Röllig, C.; Cavenagh, J.; Deeren, D.; Girshova, L.; Krauter, J.; Martinelli, G.; Montesinos, P.; Schäfer, J.A.; Ottmann, O.; et al. Idasanutlin plus cytarabine in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia: Results of the MIRROS trial. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 4147–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LoRusso, P.; Yamamoto, N.; Patel, M.R.; Laurie, S.A.; Bauer, T.M.; Geng, J.; Davenport, T.; Teufel, M.; Li, J.; Lahmar, M.; et al. The MDM2-p53 Antagonist Brigimadlin (BI 907828) in Patients with Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors: Results of a Phase Ia, First-in-Human, Dose-Escalation Study. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 1802–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.; Lamarca, A.; Choi, H.J.; Vogel, A.; Pishvaian, M.J.; Goyal, L.; Ueno, M.; Märten, A.; Teufel, M.; Geng, L.; et al. Brightline-2: A phase IIa/IIb trial of brigimadlin (BI 907828) in advanced biliary tract cancer, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma or other solid tumors. Future Oncol. 2024, 20, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaeva, N.; Bozko, P.; Enge, M.; Protopopova, M.; Verhoef, L.G.; Masucci, M.; Pramanik, A.; Selivanova, G. Small molecule RITA binds to p53, blocks p53-HDM-2 interaction and activates p53 function in tumors. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 1321–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbrava, E.E.; Stinchcombe, T.E.; Gounder, M.; Cote, G.M.; Hanna, G.J.; Sumrall, B.; Wise-Draper, T.M.; Kanaan, M.; Duffy, S.; Sumey, C.; et al. Milademetan in advanced solid tumors with MDM2 amplification and wild-type TP53: Pre-clinical and phase 2 clinical trial results. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, OF1–OF10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wen, X.; Peng, R.; Pan, Q.; Weng, D.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Men, L.; Wang, H.; et al. A first-in-human phase I study of a novel MDM2/p53 inhibitor alrizomadlin in advanced solid tumors. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaseem, A.M. Advancements in MDM2 inhibition: Clinical and pre-clinical investigations of combination therapeutic regimens. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 101790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Halliday, G.C.; Berry, P.; Rousseau, R.F.; Middleton, S.A.; Nichols, G.L.; Del Bello, F.; Piergentili, A.; Newell, D.R.; et al. Structurally diverse MDM2-p53 antagonists act as modulators of MDR-1 function in neuroblastoma. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Zeng, S.; Dai, X.; Ding, Y.; Huang, C.; Ruan, R.; Xiong, J.; Tang, X.; Deng, J. MDM2 inhibitors in cancer immunotherapy: Current status and perspective. Genes Dis. 2024, 11, 101279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pairawan, S.; Zhao, M.; Yuca, E.; Annis, A.; Evans, K.; Sutton, D.; Carvajal, L.; Ren, J.G.; Santiago, S.; Guerlavais, V.; et al. First in class dual MDM2/MDMX inhibitor ALRN-6924 enhances antitumor efficacy of chemotherapy in TP53 wild-type hormone receptor-positive breast cancer models. Breast Cancer Res. 2021, 23, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.N.; Patel, M.R.; Bauer, T.M.; Goel, S.; Falchook, G.S.; Shapiro, G.I.; Chung, K.Y.; Infante, J.R.; Conry, R.M.; Rabinowits, G.; et al. Phase 1 Trial of ALRN-6924, a Dual Inhibitor of MDMX and MDM2, in Patients with Solid Tumors and Lymphomas Bearing Wild-type TP53. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 5236–5247, Erratum in Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churcher, I. Protac-induced protein degradation in drug discovery: Breaking the Rules or Just Making New Ones? J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutake, Y.K.; Mayo, M.F.; Dumont, N.; Filiatrault, J.; Breitkopf, S.B.; Cho, P.; Chen, D.; Dixit, V.S.; Proctor, W.R.; Kuhn, E.W.; et al. KT-253, a Novel MDM2 Degrader and p53 Stabilizer, Has Superior Potency and Efficacy than MDM2 Small-Molecule Inhibitors. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2025, 24, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerlavais, V.; Sawyer, T.K.; Carvajal, L.; Chang, Y.S.; Graves, B.; Ren, J.G.; Sutton, D.; Olson, K.A.; Packman, K.; Darlak, K.; et al. Discovery of Sulanemadlin (ALRN-6924), the First Cell-Permeating, Stabilized α-Helical Peptide in Clinical Development. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 9401–9417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashique, S.; Debnath, B.; Ramzan, M.; Taj, T.; Islam, A.; Chaudhary, P.; Kaushik, M.; Garg, A.; Sen, A.; Raveendran, C.; et al. A critical review of the synergistic potential of targeting p53 and CAR T cell therapy in cancer treatment. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 189, 118308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Laroche-Clary, A.; Verbeke, S.; Derieppe, M.A.; Italiano, A. MDM2 Antagonists Induce a Paradoxical Activation of Erk1/2 through a P53-Dependent Mechanism in Dedifferentiated Liposarcomas: Implications for Combinatorial Strategies. Cancers 2020, 12, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkrief, A.; Odintsov, I.; Smith, R.S.; Vojnic, M.; Hayashi, T.; Khodos, I.; Markov, V.; Liu, Z.; Lui, A.J.W.; Bloom, J.L.; et al. Combination of MDM2 and Targeted Kinase Inhibitors Results in Prolonged Tumor Control in Lung Adenocarcinomas with Oncogenic Tyrosine Kinase Drivers and MDM2 Amplification. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, e2400241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, E.M.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Chromik, J.; Chatterjee, M.; Bauer, S.; Lin, C.C.; Suarez, C.; de Vos, F.; Steeghs, N.; Cassier, P.A.; et al. Results from a First-in-Human Phase I Study of Siremadlin (HDM201) in Patients with Advanced Wild-Type TP53 Solid Tumors and Acute Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daver, N.G.; Dail, M.; Garcia, J.S.; Jonas, B.A.; Yee, K.W.L.; Kelly, K.R.; Vey, N.; Assouline, S.; Roboz, G.J.; Paolini, S.; et al. Venetoclax and idasanutlin in relapsed/refractory AML: A nonrandomized, open-label phase 1b trial. Blood 2023, 141, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, L.A.; Neriah, D.B.; Senecal, A.; Benard, L.; Thiruthuvanathan, V.; Yatsenko, T.; Narayanagari, S.R.; Wheat, J.C.; Todorova, T.I.; Mitchell, K.; et al. Dual inhibition of MDMX and MDM2 as a therapeutic strategy in leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaao3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Jin, H.; Cai, Y. Unveiling therapeutic prospects: Targeting MDM-2 in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 43, 7465–7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, M.; Tafuri, A.; Cima, L.; Cerruto, M.A.; Milella, M.; Zivi, A.; Buti, S.; Bersanelli, M.; Fornarini, G.; Vellone, V.G.; et al. MDM2 gene amplification as selection tool for innovative targeted approaches in PD-L1 positive or negative muscle-invasive urothelial bladder carcinoma. J. Clin. Pathol. 2022, 75, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forslund, A.; Zeng, Z.; Qin, L.X.; Rosenberg, S.; Ndubuisi, M.; Pincas, H.; Gerald, W.; Notterman, D.A.; Barany, F.; Paty, P.B. MDM2 gene amplification is correlated to tumor progression but not to the presence of SNP309 or TP53 mutational status in primary colorectal cancers. Mol. Cancer Res. 2008, 6, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russano, F.; Del Fiore, P.; Cassalia, F.; Benna, C.; Dall’Olmo, L.; Rastrelli, M.; Mocellin, S. Do Tumor SURVIVIN and MDM2 Expression Levels Correlate with Treatment Response and Clinical Outcome in Isolated Limb Perfusion for In-Transit Cutaneous Melanoma Metastases? J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellot Ortiz, K.I.; Rechberger, J.S.; Nonnenbroich, L.F.; Daniels, D.J.; Sarkaria, J.N. MDM2 Inhibition in the Treatment of Glioblastoma: From Concept to Clinical Investigation. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaubel, R.A.; Zhang, W.; Oh, J.H.; Mladek, A.C.; Pasa, T.I.; Gantchev, J.K.; Waller, K.L.; Baquer, G.; Stopka, S.A.; Regan, M.S.; et al. Preclinical Modeling of Navtemadlin Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Efficacy in IDH-Wild-type Glioblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 3771–3786. [Google Scholar]

- Di Grazia, G.; Conti, C.; Nucera, S.; Stella, S.; Massimino, M.; Giuliano, M.; Schettini, F.; Vigneri, P.; Martorana, F. Bridging the Gap: The role of MDM2 inhibition in overcoming treatment resistance in breast cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2025, 214, 104834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousuf, A.; Khan, N.U. Targeting MDM2-p53 interaction for breast cancer therapy. Oncol. Res. 2025, 33, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, H.T. MAPK signal pathways in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell Res. 2002, 12, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, W.; Zhao, Y.; McEachern, D.; Meaux, I.; Barrière, C.; Stuckey, J.A.; Meagher, J.L.; Bai, L.; Liu, L.; et al. SAR405838: An optimized inhibitor of MDM2-p53 interaction that induces complete and durable tumor regression. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 5855–5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollner, A.; Rudolph, D.; Weyer-Czernilofsky, U.; Baumgartinger, R.; Jung, P.; Weinstabl, H.; Ramharter, J.; Grempler, R.; Quant, J.; Rinnenthal, J.; et al. Discovery and Characterization of Brigimadlin, a Novel and Highly Potent MDM2-p53 Antagonist Suitable for Intermittent Dose Schedules. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2024, 23, 1689–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trial (Drug/Regimen) | ORR (Objective Response Rate) | PFS (Progression-Free Survival) or Equivalent | Hematologic Adverse Events Grade 3–4 (Incidence) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIRROS (Phase 3) | ORR: 38.8% Placebo-C: 22.0% | Median Event-Free Survival (EFS): Idasa-C: 6.3 weeks Placebo-C: 4.4 weeks | • Febrile Neutropenia: Idasa-C: 52.5%; Placebo-C: 49.3% • Thrombocytopenia: Idasa-C: 40.8%; Placebo-C: 47.9% • Anemia: Idasa-C: 23.2%; Placebo-C: 28.1% |

| MANTRA-2 (Phase 2) | ORR: 3.2% (1/31) (95% CI, 0.1–16.7%), | Median PFS: 3.5 months (95% CI, 1.8–3.7 months), | • Thrombocytopenia: 25.0% • Neutropenia: 17.5% • Anemia: 12.5% • Leukopenia: 10.0% |

| Alrizomadlin (Phase 1) | ORR: 10.0% (2/20) (95% CI, 1.2% to 31.7%), | Median PFS: 6.1 months (95% CI, 1.7–10.4 months), | • Lymphocytopenia: 33.3% • Thrombocytopenia: 33.3% • Neutropenia: 23.8% • Anemia: 23.8% • Leukopenia: 23.8% • Febrile Neutropenia: 9.5% |

| Compound Name | Clinical Phase | Study ID |

|---|---|---|

| Nutlin-3a (RG7112) | Phase I | NCT00623870, NCT00559533 |

| Idasanutlin (RG7388) | Phase III | NCT02545283 (MIRROS), NCT02624986, NCT03566485 |

| MI-77301 (SAR405838) | Phase I | NCT01636479 |

| AMG-232 (Navtemadlin, KRT-232) | Phase I–III | NCT01723020, NCT03662126, NCT04116541 |

| DS-3032b (Milademetan) | Phase I/II | NCT01877382, NCT02343172, NCT05012397 |

| BI 907828 (Brigimadlin) | Phase I–III | NCT03449381 (Brightline-2), NCT06058793 (Brightline-4) |

| APG-115 (Alrizomadlin) | Phase I/II | NCT02935907, NCT03781986, NCT04785196, CTR20170975 |

| HDM201 (Siremadlin) | Phase I/II | NCT02143635, NCT03107780 |

| ALRN-6924 (Sulanemadlin) | Phase I/II | NCT02264613 |

| KT-253 | Phase I (ongoing) | NCT05775406 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Russano, F.; Sturlese, M.; Dall’Olmo, L.; Callegarin, F.; Brugnolo, D.; Del Fiore, P.; Patti, V.; Purpura, A.; Moro, S.; Rastrelli, M.; et al. MDM2 in Tumor Biology and Cancer Therapy: A Review of Current Clinical Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010099

Russano F, Sturlese M, Dall’Olmo L, Callegarin F, Brugnolo D, Del Fiore P, Patti V, Purpura A, Moro S, Rastrelli M, et al. MDM2 in Tumor Biology and Cancer Therapy: A Review of Current Clinical Trials. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010099

Chicago/Turabian StyleRussano, Francesco, Mattia Sturlese, Luigi Dall’Olmo, Francesco Callegarin, Davide Brugnolo, Paolo Del Fiore, Vittoria Patti, Arianna Purpura, Stefano Moro, Marco Rastrelli, and et al. 2026. "MDM2 in Tumor Biology and Cancer Therapy: A Review of Current Clinical Trials" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010099

APA StyleRussano, F., Sturlese, M., Dall’Olmo, L., Callegarin, F., Brugnolo, D., Del Fiore, P., Patti, V., Purpura, A., Moro, S., Rastrelli, M., & Mocellin, S. (2026). MDM2 in Tumor Biology and Cancer Therapy: A Review of Current Clinical Trials. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010099