Anticancer Secondary Metabolites Produced by Fungi: Potential and Representative Compounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

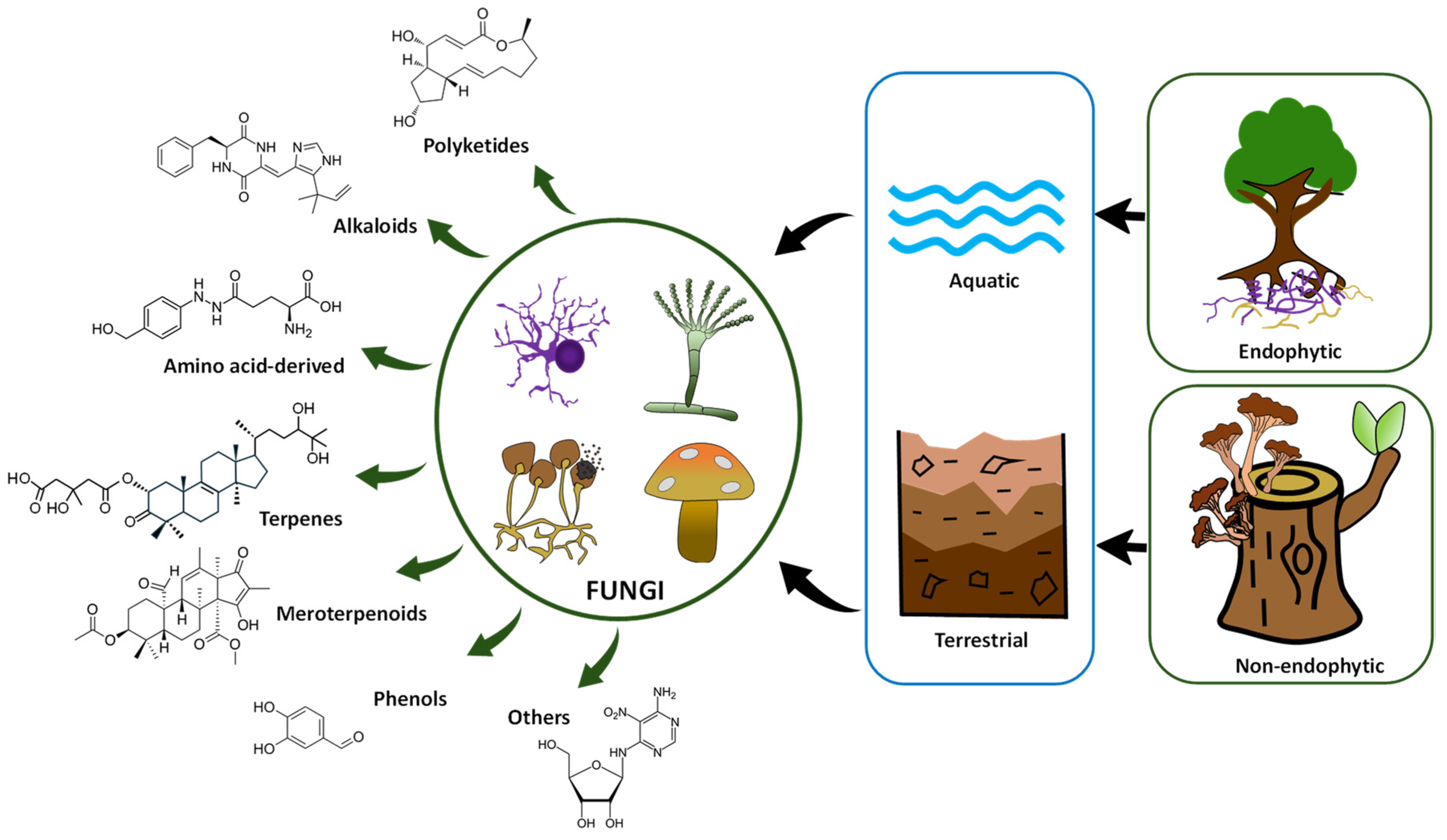

2. Fungal Secondary Metabolism as a Source of Bioactive Compounds

3. Potential and Representative Anticancer Compounds Derived from Fungi

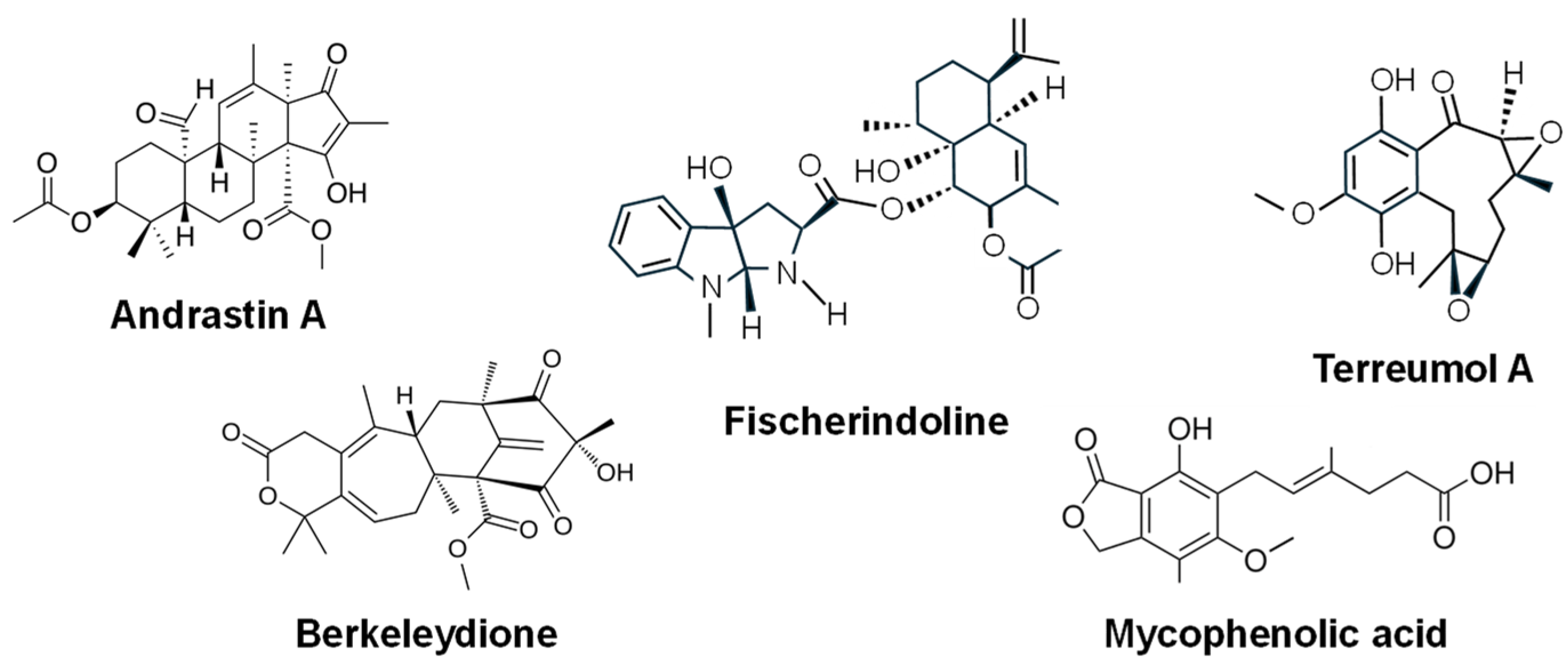

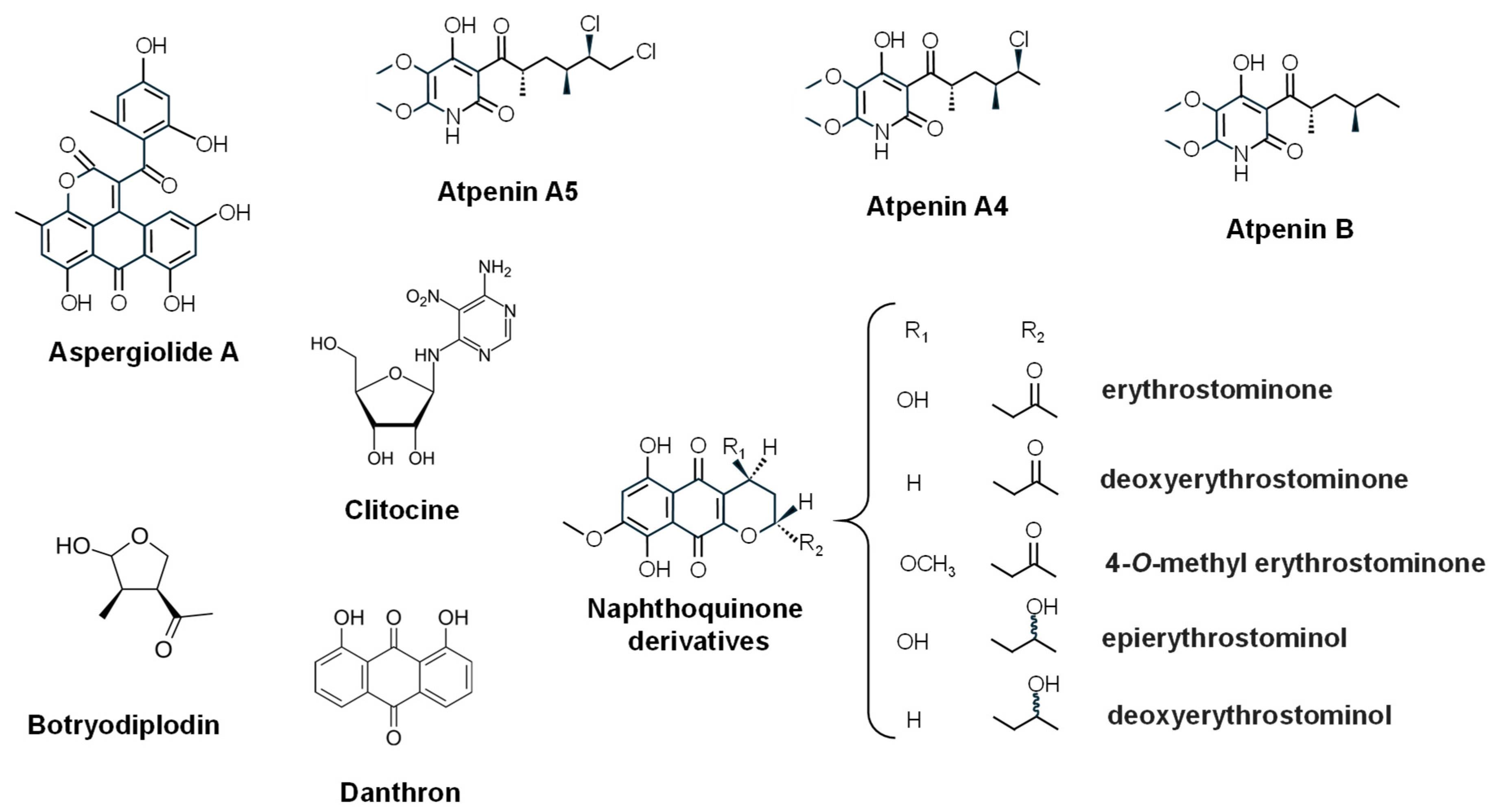

3.1. Polyketides (PKs)

3.2. Amino Acid-Derived Molecules

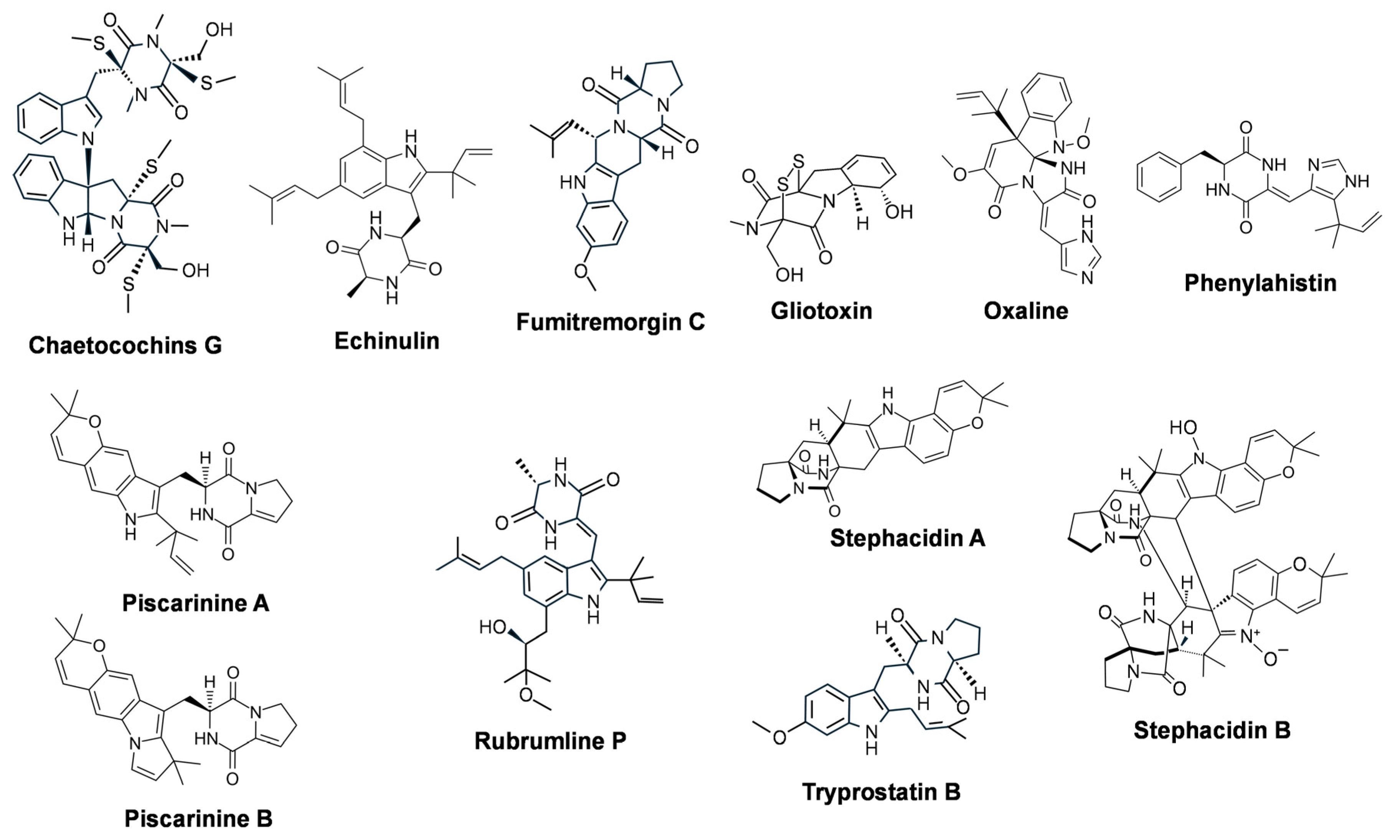

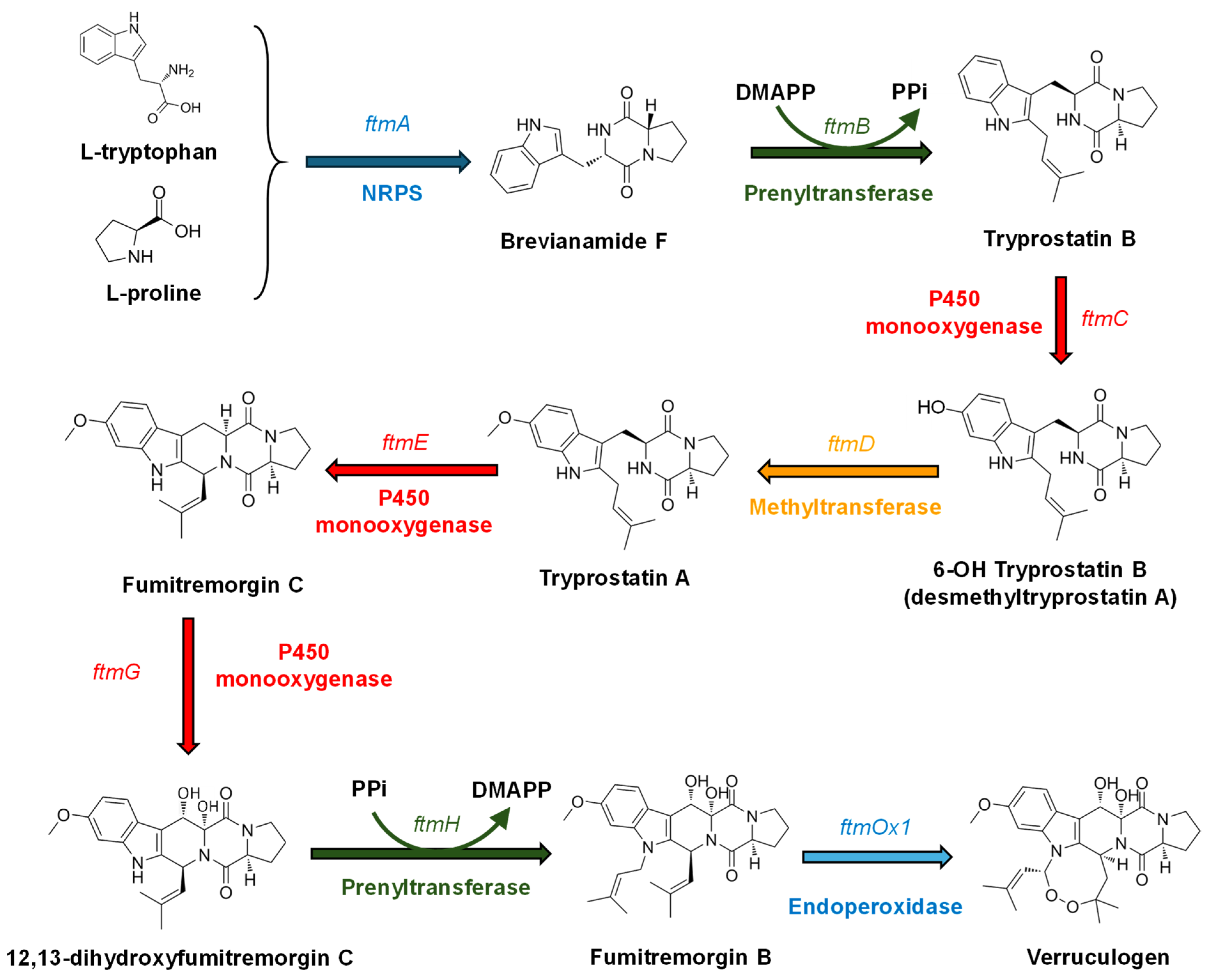

3.2.1. Diketopiperazine (DKP) Alkaloids: Representative Molecules and Biosynthesis

3.2.2. Other Amino-Acid Derived Compounds

3.3. Terpenes

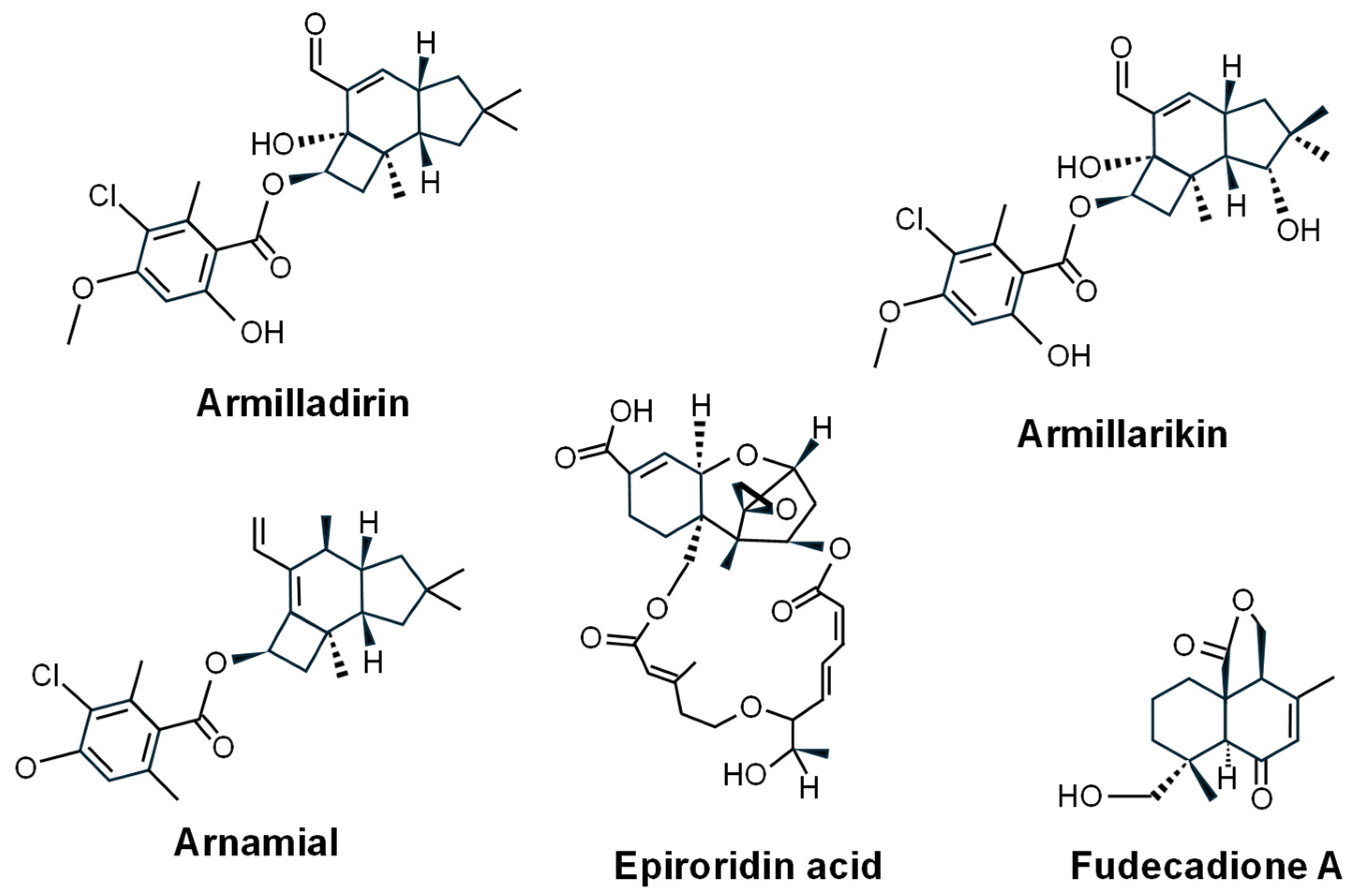

3.3.1. Sesquiterpenes

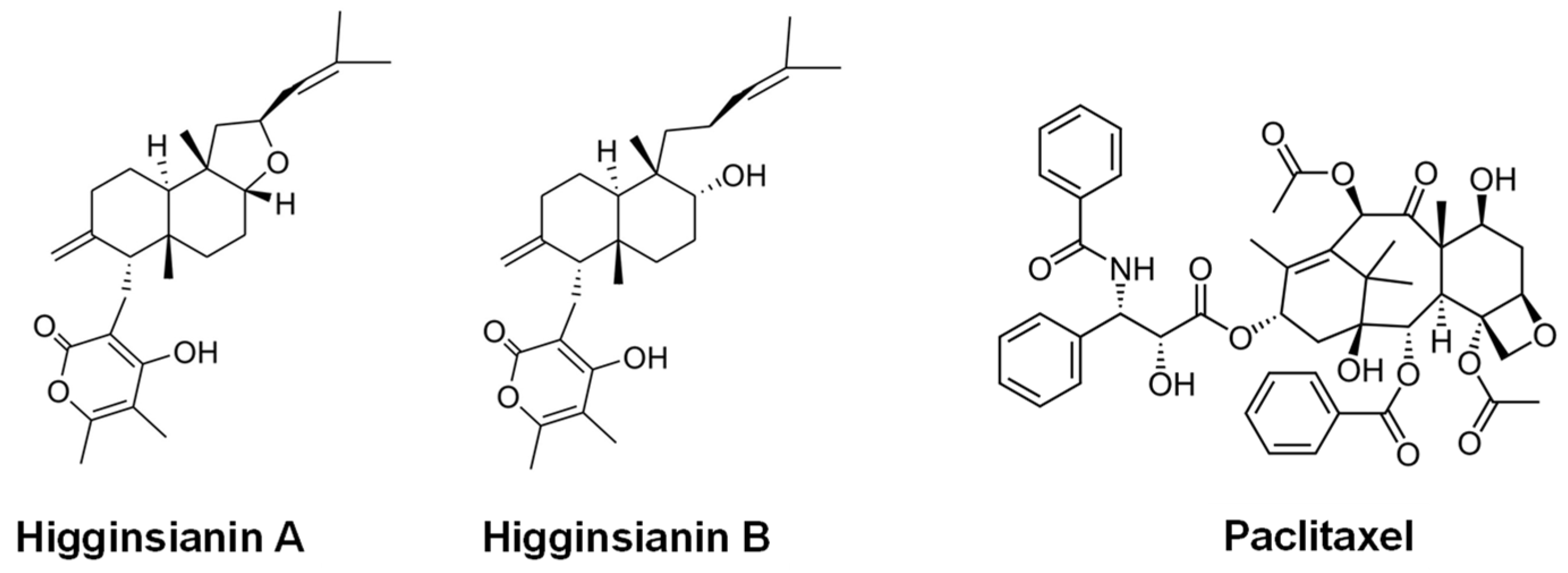

3.3.2. Paclitaxel and Other Diterpenes

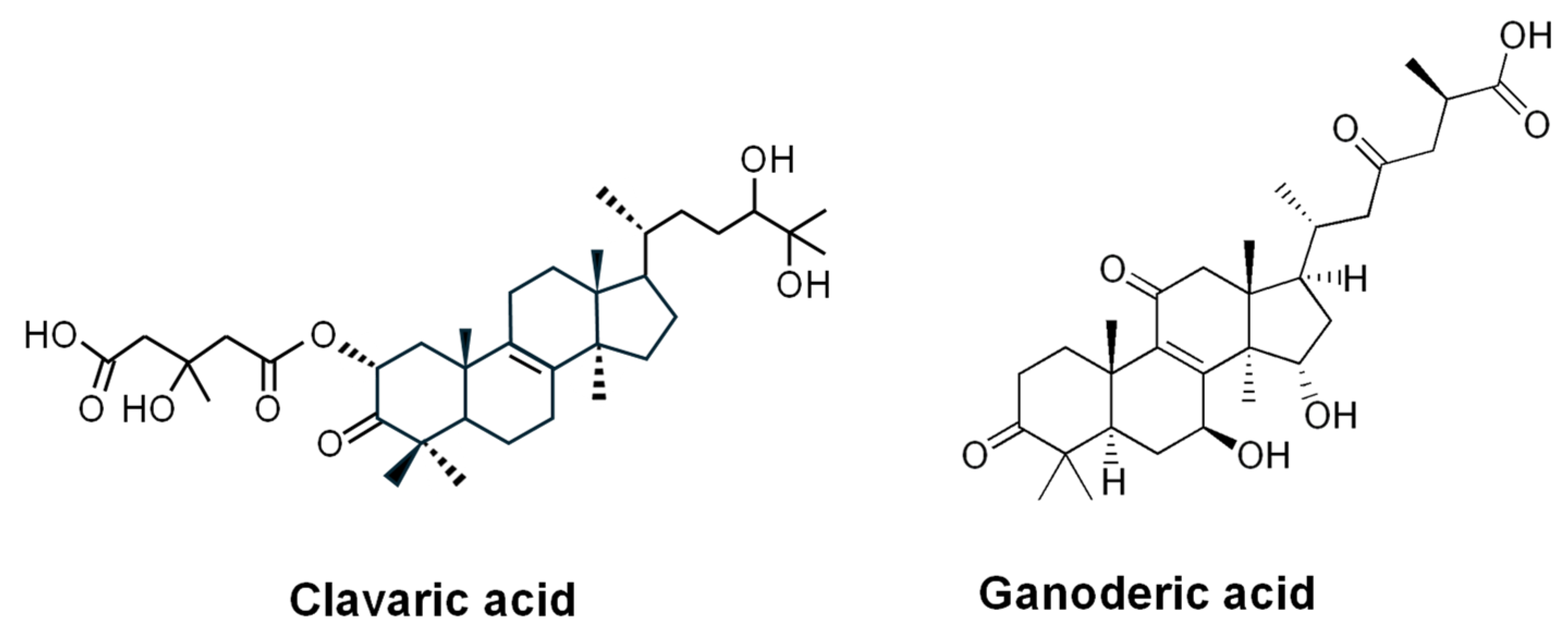

3.3.3. Triterpenes

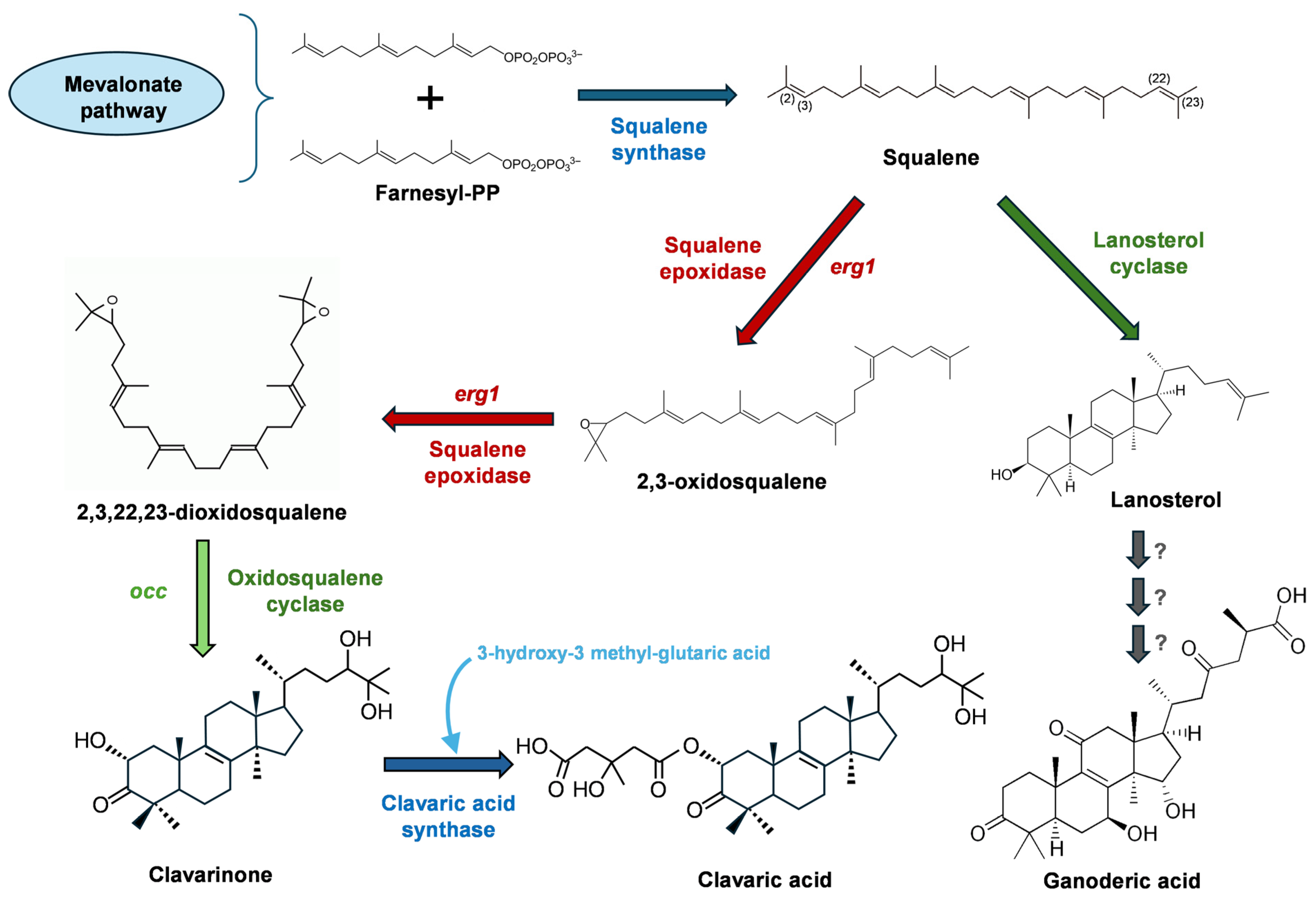

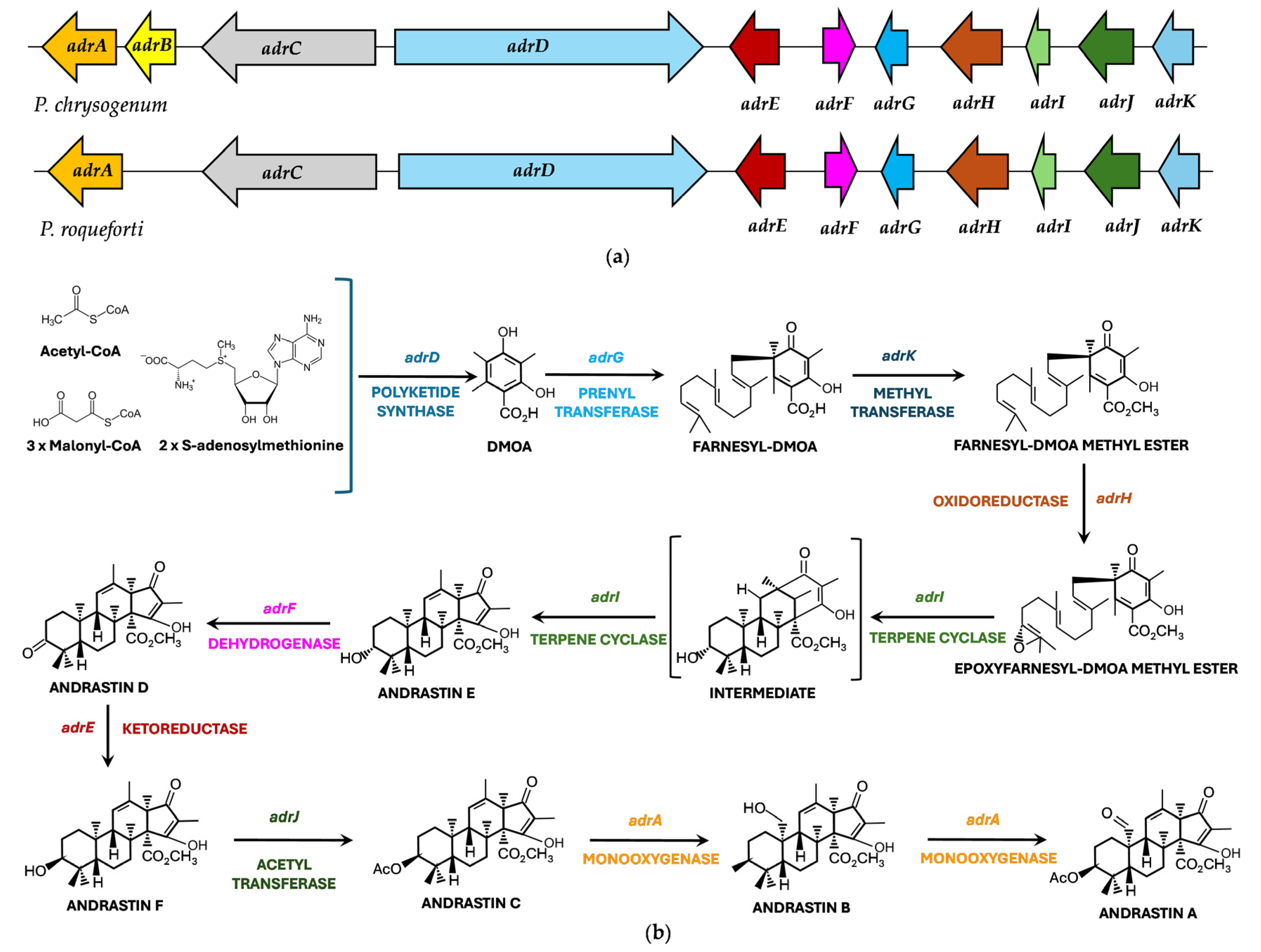

3.3.4. Meroterpenoids

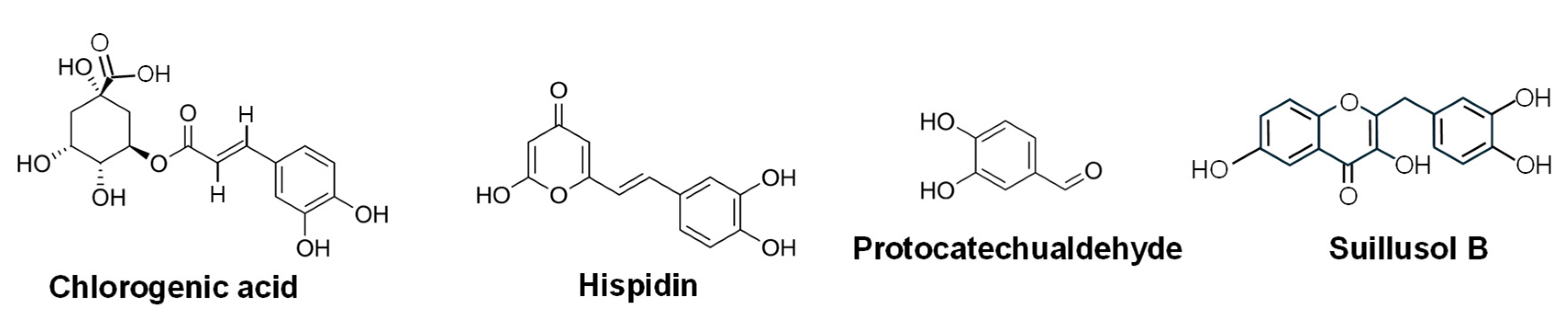

3.4. Phenolic Compounds

3.5. Other Compounds

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DKP | Diketopiperazine |

| DMOA | 3,5-dimethylorsellinic acid |

| HMG | Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl |

| NRP | Non-ribosomal peptides |

| NRPS | NRP synthetase |

| OSCC | Oxidosqualene–clavarinone cyclase |

| OSLC | Oxidosqualene–lanosterol cyclase |

| PK | Polyketide |

| PKS | PK synthase |

References

- Saeed, A.; Jabeen, A.; Mushtaq, I.; Murtaza, I. Cancer: Insight and strategies to reduce the burden. In Pathophysiology of Cancer: An Interdisciplinary Approach; Rezaei, N., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 22, pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, G.M. The Development and causes of cancer. In The Cell: A Molecular Approach, 2nd ed.; Cooper, G.M., Ed.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sinkala, M. Mutational landscape of cancer-driver genes across human cancers. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gach-Janczak, K.; Drogosz-Stachowicz, J.; Janecka, A.; Wtorek, K.; Mirowski, M. Historical perspective and current trends in anticancer drug development. Cancers 2024, 16, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chunarkar-Patil, P.; Kaleem, M.; Mishra, R.; Ray, S.; Ahmad, A.; Verma, D.; Bhayye, S.; Dubey, R.; Singh, H.; Kumar, S. Anticancer drug discovery based on natural products: From computational approaches to clinical studies. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asma, S.T.; Acaroz, U.; Imre, K.; Morar, A.; Shah, S.R.A.; Hussain, S.Z.; Arslan-Acaroz, D.; Demirbas, H.; Hajrulai-Musliu, Z.; Istanbullugil, F.R.; et al. Natural products/bioactive compounds as a source of anticancer drugs. Cancers 2022, 14, 6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seca, A.; Pinto, D. Plant secondary metabolites as anticancer agents: Successes in clinical trials and therapeutic application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, E.T.; Meiller-Legrand, T.A.; Foster, K.R. The evolution and ecology of bacterial warfare. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R521–R537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, C.; Barredo, J.L. Worldwide Clinical Demand for Antibiotics: Is It a Real Countdown? In Antimicrobial Therapies: Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2296, pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Evidente, A. Advances on anticancer fungal metabolites: Sources, chemical and biological activities in the last decade (2012–2023). Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2024, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, C.; Yang, C. Biological activity of secondary metabolites of actinomycetes and their potential sources as antineoplastic drugs: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1550516, Erratum in Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1672871.. [Google Scholar]

- Situmorang, P.C.; Ilyas, S.; Nugraha, S.E.; Syahputra, R.A.; Nik Abd Rahman, N.M.A. Prospects of compounds of herbal plants as anticancer agents: A comprehensive review from molecular pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1387866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhgun, A.A. Fungal BGCs for production of secondary metabolites: Main types, central roles in strain improvement, and regulation according to the piano principle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barka, E.A.; Vatsa, P.; Sanchez, L.; Gaveau-Vaillant, N.; Jacquard, C.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Klenk, H.P.; Clément, C.; Ouhdouch, Y.; van Wezel, G.P. Taxonomy, physiology, and natural products of actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015, 80, 1–43, Erratum in Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.2016, 80, iii.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, C.; Ibañez, A.; Garrido-Chamorro, S.; Barredo, J.L. The immunosuppressant Tacrolimus (FK506) facing the 21st century: Past findings, present applications and future trends. Fermentation 2024, 10, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, C.; Albillos, S.M.; García-Estrada, C. Penicillium chrysogenum: Beyond the penicillin. In Advances in Applied Microbiology; Gadd, G.M., Sariaslani, S., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2024; Volume 127, pp. 143–221. [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro, C.; Martínez-Cámara, S.; García-Estrada, C.; de la Torre, M.; Barredo, J.L. Beta-lactam antibiotics. In Antibiotics—Therapeutic Spectrum and Limitations; Dhara, A.K., Nayak, A.K., Chattopadhyay, D., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 89–122. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, R.H.; Krishnan, P.; Maheshwari, V.L. Production of lovastatin by wild strains of Aspergillus terreus. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011, 6, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbett, D.; Nagy, L.G.; Nilsson, R.H. Fungal diversity, evolution, and classification. Curr. Biol. 2025, 35, R463–R469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo-Ortiz, M.A.; Gabaldón, T. Fungal evolution: Diversity, taxonomy and phylogeny of the Fungi. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2019, 94, 2101–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniyam, T.; Choi, S.R.; Nathan, V.K.; Basu, A.; Lee, J.H. A new perspective on metabolites and bioactive compounds from fungi. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2023, 51, 1795–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, K.; Kapoor, N.; Kaur, H.; Abu-Seer, E.A.; Tariq, M.; Siddiqui, S.; Yadav, V.K.; Niazi, P.; Kumar, P.; Alghamdi, S. A comprehensive review of the diversity of fungal secondary metabolites and their emerging applications in healthcare and environment. Mycobiology 2024, 52, 335–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, H.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Wu, J. Lentinan progress in inflammatory diseases and tumor diseases. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.F.; Garcia-Estrada, C.; Zeilinger, S. (Eds.) Biosynthesis and Molecular Genetics of Fungal Secondary Metabolites; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, N.P. Fungal secondary metabolism: Regulation, function and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reveglia, P.; Paolillo, C.; Corso, G. The significance of fungal specialized metabolites in One Health perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Shi, G.; Xu, X.; Guo, X.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Wu, Q.; Yin, W.B. Global analysis of natural products biosynthetic diversity encoded in fungal genomes. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bills, G.F.; Gloer, J.B. Biologically active secondary metabolites from the fungi. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, FUNK-0009-2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora Verasztó, H.; Logotheti, M.; Albrecht, R.; Leitner, A.; Zhu, H.; Hartmann, M.D. Architecture and functional dynamics of the pentafunctional AROM complex. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaggs, A.R. The biosynthesis of shikimate metabolites. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2003, 20, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Polyketide biosynthesis beyond the type I, II and III polyketide synthase paradigms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2003, 7, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chooi, Y.-H.; Cacho, R.; Tang, Y. Identification of the viridicatumtoxin and griseofulvin gene clusters from Penicillium aethiopicum. Chem. Biol. 2010, 17, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, T.; Ebizuka, Y.; Fujii, I. Analysis of subunit interactions in the iterative type I polyketide synthase ATX from Aspergillus terreus. ChemBioChem 2006, 7, 1869–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Su, X.; Qu, H.; Duan, X.; Jiang, Y. Biosynthesis, regulation, and biological significance of fumonisins in fungi: Current status and prospects. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 48, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Döhren, H. Biochemistry and general genetics of nonribosomal peptide synthetases in fungi. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2004, 88, 217–264. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, J.F.; Ullán, R.V.; García-Estrada, C. Regulation and compartmentalization of β-lactam biosynthesis. Microb. Biotechnol. 2010, 3, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmann, J.; Wenger, R.M.; Kleinkauf, H.; Lawen, A. Mechanism of cyclosporin A biosynthesis. Evidence for synthesis via a single linear undecapeptide precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 2841–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaki, T.; Minami, A.; Oikawa, H. Recent advances in the biosynthesis of ribosomally synthesized and posttranslationally modified peptides of fungal origin. J. Antibiot. 2023, 76, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, E.; Künzler, M. Discovery of novel fungal RiPP biosynthetic pathways and their application for the development of peptide therapeutics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5567–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Hernández, R.A.; Valdez-Cruz, N.A.; Macías-Rubalcava, M.L.; Trujillo-Roldán, M.A. Overview of fungal terpene synthases and their regulation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barredo, J.L.; García-Estrada, C.; Kosalkova, K.; Barreiro, C. Biosynthesis of astaxanthin as a main carotenoid in the heterobasidiomycetous yeast Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudzynski, B. Gibberellin biosynthesis in fungi: Genes, enzymes, evolution, and impact on biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 66, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorrilla, J.G.; Evidente, A. Structures and biological activities of alkaloids produced by mushrooms, a fungal subgroup. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Garcia, J.; Guimarães, R.; Palito, C.; Lemos, A.; Barros, L.; Alves, M.J. Alkaloids from fungi. In Natural Secondary Metabolites; Carocho, M., Heleno, S.A., Barros, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubczyk, D.; Cheng, J.Z.; O’Connor, S.E. Biosynthesis of the ergot alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1328–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Estrada, C.; Ullán, R.V.; Albillos, S.M.; Fernández-Bodega, M.A.; Durek, P.; von Döhren, H.; Martín, J.F. A single cluster of coregulated genes encodes the biosynthesis of the mycotoxins roquefortine C and meleagrin in Penicillium chrysogenum. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 1499–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kronstad, J.W.; Jung, W.H. Siderophore biosynthesis and transport systems in model and pathogenic fungi. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 1551–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, Y.; Jenner, M.; Tang, Y. Fungal siderophore biosynthesis catalysed by an iterative nonribosomal peptide synthetase. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 11525–11530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hissen, A.H.; Moore, M.M. Site-specific rate constants for iron acquisition from transferrin by the Aspergillus fumigatus siderophores N′,N″,N‴-triacetylfusarinine C and ferricrocin. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 10, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happacher, I.; Aguiar, M.; Alilou, M.; Abt, B.; Baltussen, T.J.H.; Decristoforo, C.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Haas, H. The siderophore ferricrocin mediates iron acquisition in Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0049623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.S.; Grieve, C.L.; Murugathasan, I.; Bennet, A.J.; Czekster, C.M.; Liu, H.; Naismith, J.; Moore, M.M. The rhizoferrin biosynthetic gene in the fungal pathogen Rhizopus delemar is a novel member of the NIS gene family. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2017, 89, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, K.M. Biosynthesis of natural products by microbial iterative hybrid PKS-NRPS. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 18228–18247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, Y.; Tokuoka, M.; Koyama, Y. Functional analysis of the cyclopiazonic acid biosynthesis gene cluster in Aspergillus oryzae RIB 40. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 2249–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Cox, R.J.; Lazarus, C.M.; Simpson, T.J. Fusarin C biosynthesis in Fusarium moniliforme and Fusarium venenatum. ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, Y.; Abe, I. Biosynthesis of fungal meroterpenoids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cocq, K.; Gurr, S.J.; Hirsch, P.R.; Mauchline, T.H. Exploitation of endophytes for sustainable agricultural intensification. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 18, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hridoy, M.; Gorapi, M.Z.H.; Noor, S.; Chowdhury, N.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Muscari, I.; Masia, F.; Adorisio, S.; Delfino, D.V.; Mazid, M.A. Putative anticancer compounds from plant-derived endophytic fungi: A review. Molecules 2022, 27, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kousar, R.; Naeem, M.; Jamaludin, M.I.; Arshad, A.; Shamsuri, A.N.; Ansari, N.; Akhtar, S.; Hazafa, A.; Uddin, J.; Khan, A.; et al. Exploring the anticancer activities of novel bioactive compounds derived from endophytic fungi: Mechanisms of action, current challenges and future perspectives. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 2897–2919. [Google Scholar]

- Sonowal, S.; Gogoi, U.; Buragohain, K.; Nath, R. Endophytic fungi as a potential source of anti-cancer drug. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stierle, A.; Strobel, G.; Stierle, D. Taxol and taxane production by Taxomyces andreanae, an endophytic fungus of pacific yew. Science 1993, 260, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gärditz, K.F.; Czesnick, H. Paclitaxel—A product of fungal secondary metabolism or an artefact? Planta Med. 2024, 90, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Hoy, M.J.; Heitman, J. Fungal pathogens. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R1163–R1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, T.W.; Boddy, L.; Jones, T.H. Functional and ecological consequences of saprotrophic fungus-grazer interactions. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1992–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bladt, T.T.; Frisvad, J.C.; Knudsen, P.B.; Larsen, T.O. Anticancer and antifungal compounds from Aspergillus, Penicillium and other filamentous fungi. Molecules 2013, 18, 11338–11376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszczenko, P.; Szewczyk-Roszczenko, O.K.; Gornowicz, A.; Iwańska, I.A.; Bielawski, K.; Wujec, M.; Bielawska, A. The anticancer potential of edible mushrooms: A review of selected species from Roztocze, Poland. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zade, S.; Upadhyay, T.K.; Rab, S.O.; Sharangi, A.B.; Lakhanpal, S.; Alabdallah, N.M.; Saeed, M. Mushroom-derived bioactive compounds pharmacological properties and cancer targeting: A holistic assessment. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Gopal, J.V.; Ren, S.; Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Gao, Z. Anticancer fungal natural products: Mechanisms of action and biosynthesis. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 202, 112502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, A. The origin of the statins. Atheroscler. Suppl. 2004, 5, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Zhu, G.; Shang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, Y. An overview on the biological activity and anti-cancer mechanism of lovastatin. Cell Signal. 2021, 87, 110122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glynn, S.A.; O’Sullivan, D.; Eustace, A.J.; Clynes, M.; O’Donovan, N. The 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, simvastatin, lovastatin and mevastatin inhibit proliferation and invasion of melanoma cells. BMC Cancer 2008, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Hu, J.W.; He, X.R.; Jin, W.L.; He, X.Y. Statins: A repurposed drug to fight cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Li, C.Y.; Tsai, Y.H.; El-Shazly, M.; Wei, C.K.; Yang, Z.J.; Chen, S.L.; Wu, C.C.; Wu, Y.C.; Chang, F.R. Bioactive polyketides from the pathogenic fungus Epicoccum sorghinum. Planta 2021, 253, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Guo, C.; Shi, D.; Meng, J.; Tian, H.; Guo, S. Discovery of natural dimeric naphthopyrones as potential cytotoxic agents through ROS-mediated apoptotic pathway. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betina, V. Biological effects of the antibiotic brefeldin A (decumbin, cyanein, ascotoxin, synergisidin): A retrospective. Folia Microbiol. 1992, 37, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Fang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Su, W. Brefeldin A, a cytotoxin produced by Paecilomyces sp. and Aspergillus clavatus isolated from Taxus mairei and Torreya grandis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2002, 34, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Xu, K.; Liu, X.M.; Zhang, P. A systematic review on secondary metabolites of Paecilomyces species: Chemical diversity and biological activity. Planta Med. 2020, 86, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Yuan, L.C.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Klausner, R.D. Rapid redistribution of Golgi proteins into the ER in cells treated with brefeldin A: Evidence for membrane cycling from Golgi to ER. Cell 1989, 56, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raistrick, H.; Smith, G. LXXI. Studies in the biochemistry of micro-organisms. XLII. The metabolic products of Aspergillus terreus Thom. A new mould metabolic product—Terrein. Biochem. J. 1935, 29, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.F.; Wang, S.Y.; Shen, H.; Yao, X.F.; Zhang, F.L.; Lai, D. The marine-derived fungal metabolite, terrein, inhibits cell proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest in human ovarian cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 34, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, S.; Zeng, M.; Chu, J.; Hu, P.; Li, J.; Guo, Q.; Lv, X.B.; Huang, G. Terrein performs antitumor functions on esophageal cancer cells by inhibiting cell proliferation and synergistic interaction with cisplatin. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 2805–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhijjleh, R.K.; Al Saeedy, D.Y.; Ashmawy, N.S.; Gouda, A.E.; Elhady, S.S.; Al-Abd, A.M. Chemomodulatory effect of the marine-derived metabolite “terrein” on the anticancer properties of gemcitabine in colorectal cancer cells. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aris, P.; Wei, Y.; Mohamadzadeh, M.; Xia, X. Griseofulvin: An updated overview of old and current knowledge. Molecules 2022, 27, 7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, D.; Rathinasamy, K.; Santra, M.K.; Wilson, L. Kinetic suppression of microtubule dynamic instability by griseofulvin: Implications for its possible use in the treatment of cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9878–9883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinasamy, K.; Jindal, B.; Asthana, J.; Singh, P.; Balaji, P.V.; Panda, D. Griseofulvin stabilizes microtubule dynamics, activates p53 and inhibits the proliferation of MCF-7 cells synergistically with vinblastine. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Fu, Y.; Fan, Q.; Lin, L.; Ning, Z.; Leng, D.; Hu, M.; She, T. Antitumor properties of griseofulvin and its toxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1459539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, E.; Nakano, H.; Morimoto, M.; Tamaoki, T. Calphostin C (UCN-1028C), a novel microbial compound, is a highly potent and specific inhibitor of protein kinase C. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989, 159, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, I.F.; Kawecki, S. The effect of calphostin C, a potent photodependent protein kinase C inhibitor, on the proliferation of glioma cells in vitro. J. Neurooncol. 1997, 31, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, A.; Maltese, W.A. Killing of cancer cells by the photoactivatable protein kinase C inhibitor, calphostin C, involves induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Neoplasia 2009, 11, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.M.; Narla, R.K.; Fang, W.H.; Chia, N.C.; Uckun, F.M. Calphostin C triggers calcium-dependent apoptosis in human acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 1998, 4, 2967–2976. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, E.; Ando, K.; Nakano, H.; Iida, T.; Ohno, H.; Morimoto, M.; Tamaoki, T. Calphostins (UCN-1028), novel and specific inhibitors of protein kinase C. I. Fermentation, isolation, physico-chemical properties and biological activities. J. Antibiot. 1989, 42, 1470–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuhide, M.; Yamada, T.; Numata, A.; Tanaka, R. Chaetomugilins, new selectively cytotoxic metabolites, produced by a marine fish-derived Chaetomium species. J. Antibiot. 2008, 61, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Jinno, M.; Kikuchi, T.; Kajimoto, T.; Numata, A.; Tanaka, R. Three new azaphilones produced by a marine fish-derived Chaetomium globosum. J. Antibiot. 2012, 65, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steyn, P.S.; Vleggaar, R. Austocystins. Six novel dihydrofuro(3′,2′:4,5)furo(3,2-b)xanthenones from Aspergillus ustus. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1974, 19, 2250–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, K.M.; Park, E.S.; Arefolov, A.; Russo, K.; Ishihara, K.; Ring, J.E.; Clardy, J.; Clarke, A.S.; Pelish, H.E. The selectivity of austocystin D arises from cell-line-specific drug activation by cytochrome P450 enzymes. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Fujieda, S.; Zhou, L.; Takikawa, M.; Kuramochi, K.; Furuya, T.; Mizumoto, A.; Kagaya, N.; Kawahara, T.; Shin-Ya, K.; et al. Cytochrome P450 2J2 is required for the natural compound austocystin D to elicit cancer cell toxicity. Cancer Sci. 2024, 115, 3054–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Qiao, K.; Gao, Z.; Meehan, M.J.; Li, J.W.; Zhao, X.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Vederas, J.C.; Tang, Y. Enzymatic synthesis of resorcylic acid lactones by cooperation of fungal iterative polyketide synthases involved in hypothemycin biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4530–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, A.; Kennedy, J.; Murli, S.; Reid, R.; Santi, D.V. Targeted covalent inactivation of protein kinases by resorcylic acid lactone polyketides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 4234–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, H.; Nishida, K.; Sugita, K.; Yoshioka, T. Antitumor efficacy of hypothemycin, a new Ras-signaling inhibitor. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1999, 90, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemphill, C.F.P.; Sureechatchaiyan, P.; Kassack, M.U.; Orfali, R.S.; Lin, W.; Daletos, G.; Proksch, P. OSMAC approach leads to new fusarielin metabolites from Fusarium tricinctum. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, C.; Sun, L.; Munro, M.H.; Santhanam, J. Polyketide and benzopyran compounds of an endophytic fungus isolated from Cinnamomum mollissimum: Biological activity and structure. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014, 4, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Robles, A.J.; King, J.B.; Powell, D.R.; Miller, A.N.; Mooberry, S.L.; Cichewicz, R.H. Crowdsourcing natural products discovery to access uncharted dimensions of fungal metabolite diversity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 804–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, A.J.; Du, L.; Cichewicz, R.H.; Mooberry, S.L. Maximiscin induces DNA damage, activates DNA damage response pathways, and has selective cytotoxic activity against a subtype of triple-negative breast cancer. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 1822–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Sirwi, A.; Eid, B.G.; Mohamed, S.G.A.; Mohamed, G.A. Fungal depsides—Naturally inspiring molecules: Biosynthesis, structural characterization, and biological activities. Metabolites 2021, 11, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lünne, F.; Niehaus, E.M.; Lipinski, S.; Kunigkeit, J.; Kalinina, S.A.; Humpf, H.U. Identification of the polyketide synthase PKS7 responsible for the production of lecanoric acid and ethyl lecanorate in Claviceps purpurea. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2020, 145, 103481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.R.; Kim, B.Y.; Oh, W.K.; Kang, D.O.; Lee, H.S.; Koshino, H.; Osada, H.; Mheen, T.I.; Ahn, J.S. CRM646-A and -B, novel fungal metabolites that inhibit heparinase. J. Antibiot. 2000, 53, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Yao, J.; Kong, J.; Yu, A.; Wei, J.; Dong, Y.; Song, R.; Shan, D.; Zhong, X.; Lv, F.; et al. 2,5-Diketopiperazines: A review of source, synthesis, bioactivity, structure, and MS fragmentation. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023, 30, 1060–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Merwe, E.; Huang, D.; Peterson, D.; Kilian, G.; Milne, P.J.; Van de Venter, M.; Frost, C. The synthesis and anticancer activity of selected diketopiperazines. Peptides 2008, 29, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanoh, K.; Kohno, S.; Asari, T.; Harada, T.; Katada, J.; Muramatsu, M.; Kawashima, H.; Sekiya, H.; Uno, I. (−)-Phenylahistin: A new mammalian cell cycle inhibitor produced by Aspergillus ustus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1997, 7, 2847–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanoh, K.; Kohno, S.; Katada, J.; Takahashi, J.; Uno, I. (−)-Phenylahistin arrests cells in mitosis by inhibiting tubulin polymerization. J. Antibiot. 1999, 52, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanoh, K.; Kohno, S.; Katada, J.; Hayashi, Y.; Muramatsu, M.; Uno, I. Antitumor activity of phenylahistin in vitro and in vivo. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1999, 63, 1130–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Nicholson, B.; Deyanat-Yazdi, G.; Potts, B.; Yoshida, T.; Oda, A.; Kitagawa, T.; Orikasa, S.; Kiso, Y.; et al. Synthesis and structure–activity relationship study of antimicrotubule agents phenylahistin derivatives with a didehydropiperazine-2,5-dione structure. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 1056–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natoli, M.; Herzig, P.; Pishali Bejestani, E.; Buchi, M.; Ritschard, R.; Lloyd, G.K.; Mohanlal, R.; Tonra, J.R.; Huang, L.; Heinzelmann, V.; et al. Plinabulin, a distinct microtubule-targeting chemotherapy, promotes M1-like macrophage polarization and anti-tumor immunity. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 644608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, J.; Chiappori, A.; Fujioka, N.; Hanna, N.H.; Feldman, L.E.; Patel, M.; Moore, D.; Chen, C.; Jabbour, S.K. Phase I/II trial of plinabulin in combination with nivolumab and ipilimumab in patients with recurrent small cell lung cancer (SCLC): Big Ten Cancer Research Consortium (BTCRC-LUN17-127) study. Lung Cancer 2024, 195, 107932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blayney, D.W.; Mohanlal, R.; Adamchuk, H.; Kirtbaya, D.V.; Chen, M.; Du, L.; Ogenstad, S.; Ginn, G.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Q. Efficacy of plinabulin vs pegfilgrastim for prevention of docetaxel-induced neutropenia in patients with solid tumors: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2145446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.B.; Kakeya, H.; Okada, G.; Onose, R.; Ubukata, M.; Takahashi, I.; Isono, K.; Osada, H. Tryprostatins A and B, novel mammalian cell cycle inhibitors produced by Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Antibiot. 1995, 48, 1382–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondoh, M.; Usui, T.; Mayumi, T.; Osada, H. Effects of tryprostatin derivatives on microtubule assembly in vitro and in situ. J. Antibiot. 1998, 51, 801–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Smith, K.S.; Deveau, A.M.; Dieckhaus, C.M.; Johnson, M.A.; Macdonald, T.I.; Cook, J.M. Biological activity of the tryprostatins and their diastereomers on human carcinoma cell lines. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 1559–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabindran, S.K.; Ross, D.D.; Doyle, L.A.; Yang, W.; Greenberger, L.M. Fumitremorgin C reverses multidrug resistance in cells transfected with the breast cancer resistance protein. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kato, N.; Suzuki, H.; Takagi, H.; Asami, Y.; Kakeya, H.; Uramoto, M.; Usui, T.; Takahashi, S.; Sugimoto, Y.; Osada, H. Identification of cytochrome P450s required for fumitremorgin biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. ChemBioChem 2009, 10, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, L.A.; Ross, D.D. Multidrug resistance mediated by the breast cancer resistance protein BCRP (ABCG2). Oncogene 2003, 22, 7340–7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, P.; Schuetz, J.D. Role of ABCG2/BCRP in biology and medicine. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2006, 46, 381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Schuetz, J.D.; Bunting, K.D.; Colapietro, A.M.; Sampath, J.; Morris, J.J.; Lagutina, I.; Grosveld, G.C.; Osawa, M.; Nakauchi, H.; et al. The ABC transporter Bcrp1/ABCG2 is expressed in a wide variety of stem cells and is a molecular determinant of the side-population phenotype. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollinsky, B.; Ludwig, L.; Hamacher, A.; Yu, X.; Kassack, M.U.; Li, S.-M. Prenylation at the indole ring leads to a significant increase of cytotoxicity of tryptophan-containing cyclic dipeptides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 3866–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.F.; Liras, P. Targeting of specialized metabolites biosynthetic enzymes to membranes and vesicles by posttranslational palmitoylation: A mechanism of non-conventional traffic and secretion of fungal metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian-Cutrone, J.; Huang, S.; Shu, Y.Z.; Vyas, D.; Fairchild, C.; Menendez, A.; Krampitz, K.; Dalterio, R.; Klohr, S.E.; Gao, Q. Stephacidin A and B: Two structurally novel, selective inhibitors of the testosterone-dependent prostate LNCaP cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 14556–14557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkola, R.; Andersson, M.A.; Hautaniemi, M.; Salkinoja-Salonen, M.S. Toxic indole alkaloids avrainvillamide and stephacidin B produced by a biocide tolerant indoor mold Aspergillus westerdijkiae. Toxicon 2015, 99, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhelifonova, V.P.; Maier, A.; Kozlovskiĭ, A.G. Effect of various factors on the biosynthesis of piscarinines, secondary metabolites of the fungus Penicillium piscarium Westling. Prikl. Biokhim. Mikrobiol. 2008, 44, 671–675. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koizumi, Y.; Arai, M.; Tomoda, H.; Omura, S. Oxaline, a fungal alkaloid, arrests the cell cycle in M phase by inhibition of tubulin polymerization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1693, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balibar, C.J.; Walsh, C.T. GliP, a multimodular nonribosomal peptide synthetase in Aspergillus fumigatus, makes the diketopiperazine scaffold of gliotoxin. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 15029–15038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.L.; Le, X.; Li, H.J.; Yang, X.L.; Chen, J.X.; Xu, J.; Liu, H.L.; Wang, L.Y.; Wang, K.T.; Hu, K.C.; et al. Exploring the chemodiversity and biological activities of the secondary metabolites from the marine fungus Neosartorya pseudofischeri. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 5657–5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, R.; Murugesan, K. Production of gliotoxin on natural substrates by Trichoderma virens. J. Basic Microbiol. 2005, 45, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Fan, Z.; Sun, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W. Dechdigliotoxins A–C, three novel disulfide-bridged gliotoxin dimers from deep-sea sediment derived fungus Dichotomomyces cejpii. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, S.S.; Ghosh, S.S.; Saini, G.K. Gliotoxin triggers cell death through multifaceted targeting of cancer-inducing genes in breast cancer therapy. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2024, 112, 108170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Lan, W.; Huang, C.; Lin, M.; Wang, Z.; Liang, W.; Iwamoto, A.; Yang, X.; Liu, H. Gliotoxin inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 6259–6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Liu, T.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, W. The toxic mechanism of gliotoxins and biosynthetic strategies for toxicity prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kashef, D.H.; Obidake, D.D.; Schiedlauske, K.; Deipenbrock, A.; Scharf, S.; Wang, H.; Naumann, D.; Friedrich, D.; Miljanovic, S.; Haj Hassani Sohi, T.; et al. Indole diketopiperazine alkaloids from the marine sediment-derived fungus Aspergillus chevalieri against pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mar. Drugs 2023, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Q.; Tong, Q.Y.; Ma, H.R.; Xu, H.F.; Hu, S.; Ma, W.; Xue, Y.B.; Liu, J.J.; Wang, J.P.; Song, H.P.; et al. Indole diketopiperazines from endophytic Chaetomium sp. 88194 induce breast cancer cell apoptotic death. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhloufi, H.; Pinon, A.; Champavier, Y.; Saliba, J.; Millot, M.; Fruitier-Arnaudin, I.; Liagre, B.; Chemin, G.; Mambu, L. In vitro antiproliferative activity of echinulin derivatives from endolichenic fungus Aspergillus sp. against colorectal cancer. Molecules 2024, 29, 4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süssmuth, R.D.; Mainz, A. Nonribosomal peptide synthesis—Principles and prospects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3770–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giessen, T.W.; Marahiel, M.A. The tRNA-dependent biosynthesis of modified cyclic dipeptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 14610–14631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiya, S.; Grundmann, A.; Li, S.-M.; Turner, G. The fumitremorgin gene cluster of Aspergillus fumigatus: Identification of a gene encoding brevianamide F synthetase. ChemBioChem 2006, 7, 1062–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundmann, A.; Kuznetsova, T.; Afiyatullov, S.S.; Li, S.M. FtmPT2, an N-prenyltransferase from Aspergillus fumigatus, catalyses the last step in the biosynthesis of fumitremorgin B. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 2059–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosalková, K.; Domínguez-Santos, R.; Coton, M.; Coton, E.; García-Estrada, C.; Liras, P.; Martín, J.F. A natural short pathway synthesizes roquefortine C but not meleagrin in three different Penicillium roqueforti strains. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 7601–7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.-M. Prenylated indole derivatives from fungi: Structure diversity, biological activities, biosynthesis and chemoenzymatic synthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, N.; Suzuki, H.; Okumura, H.; Takahashi, S.; Osada, H. A point mutation in ftmD blocks the fumitremorgin biosynthetic pathway in Aspergillus fumigatus strain Af293. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2013, 77, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundmann, A.; Li, S.W.-M. Overproduction, purification and characterization of FtmPT1, a brevianamide F prenyltransferase from Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbiology 2005, 151, 2199–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-M. Genome Mining and Biosynthesis of Fumitremorgin-Type Alkaloids in Ascomycetes. J. Antibiot. 2011, 64, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Bodega, Á.; Álvarez-Álvarez, R.; Liras, P.; Martín, J.F. Silencing of a second dimethylallyl tryptophan synthase of Penicillium roqueforti reveals a novel clavine alkaloid gene cluster. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 6111–6121, Erratum in Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 7767–7768.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffan, N.; Grundmann, A.; Yin, W.B.; Kremer, A.; Li, S.M. Indole prenyltransferases from fungi: A new enzyme group with high potential for the production of prenylated indole derivatives. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffan, N.; Grundmann, A.; Afiyatullov, S.; Ruan, H.; Li, S.-M. FtmOx1, a non-heme Fe(II) and alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase, catalyses the endoperoxide formation of verruculogen in Aspergillus fumigatus. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 4082–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunham, N.P.; Pantoja, J.M.R.; Zhang, B.; Rajakovich, L.J.; Allen, B.D.; Krebs, C.; Boal, A.K.; Bollinger, J.M., Jr. Hydrogen donation but not abstraction by a tyrosine (Y68) during endoperoxide installation by verruculogen synthase (FtmOx1). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 9964–9979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, Z.; Cen, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhou, J. Structural insight into the catalytic mechanism of the endoperoxide synthase FtmOx1. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202112063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miłaczewska, A.; Borowski, T. On the reaction mechanism of an endoperoxide ring formation by fumitremorgin B endoperoxidase. The right arrangement makes a difference. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 16211–16221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nies, J.; Li, S.-M. Prenylation and dehydrogenation of a C2-reversely prenylated diketopiperazine as a branching point in the biosynthesis of echinulin family alkaloids in Aspergillus ruber. ACS Chem. Biol. 2021, 16, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, R.; Li, Z.; Qin, Q.; Bai, H.; Meng, C.; Wei, R.; Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Kashif, M.; He, S.; et al. NRPS-like gene LYS2 contributed to the biosynthesis of cyclo(Pro-Val) in a multistress-tolerant aromatic probiotic, Meyerozyma guilliermondii GXDK6. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 507–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, W. Das neue Antibiotikum Xanthocillin [The new antibiotic xanthocillin]. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 1954, 79, 1080–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Li, X.; Meng, L.; Li, C.; Gao, S.; Huang, C.; Wang, B. Chemical profile of the secondary metabolites produced by a deep-sea sediment-derived fungus Penicillium commune SD-118. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2012, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, F.Y.; Won, T.H.; Raffa, N.; Baccile, J.A.; Wisecaver, J.; Rokas, A.; Schroeder, F.C.; Keller, N.P. Fungal isocyanide synthases and xanthocillin biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. mBio 2018, 9, e00785-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, K.; Kaleem, S.; Ma, M.; Lian, X.; Zhang, Z. Antiglioma natural products from the marine-associated fungus Penicillium sp. ZZ1750. Molecules 2022, 27, 7099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Shang, Z.; Jiao, B.; Yuan, B.; Sun, W.; Wang, B.; Miao, M.; Huang, C. SD118-xanthocillin X (1), a novel marine agent extracted from Penicillium commune, induces autophagy through the inhibition of the MEK/ERK pathway. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A.M.; Hufford, C.D.; Robertson, L.W. Two metabolites from Aspergillus flavipes. Lloydia 1977, 40, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Houbraken, J.; Popma, S.; Samson, R.A. Two new Penicillium species Penicillium buchwaldii and Penicillium spathulatum, producing the anticancer compound asperphenamate. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2013, 339, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romsdahl, J.; Wang, C.C.C. Recent advances in the genome mining of Aspergillus secondary metabolites (covering 2012–2018). Medchemcomm 2019, 10, 840–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, Q.; Yuan, L.; Miao, C.; Mu, X.; Xiao, W.; Li, J.; Sun, T.; Ma, E. JNK-dependent Atg4 upregulation mediates asperphenamate derivative BBP-induced autophagy in MCF-7 cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012, 263, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subko, K.; Wang, X.; Nielsen, F.H.; Isbrandt, T.; Gotfredsen, C.H.; Ramos, M.C.; Mackenzie, T.; Vicente, F.; Genilloud, O.; Frisvad, J.C.; et al. Mass spectrometry guided discovery and design of novel asperphenamate analogs from Penicillium astrolabium reveals an extraordinary NRPS flexibility. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 618730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avola, R.; Graziano, A.C.E.; Madrid, A.; Clericuzio, M.; Cardile, V.; Russo, A. Pholiotic acid promotes apoptosis in human metastatic melanoma cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 390, 110894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, M.; Beppu, H.; Akiyama, H.; Wakamatsu, K.; Ito, S.; Kawamoto, Y.; Shimpo, K.; Sumiya, T.; Koike, T.; Matsui, T. Agaritine purified from Agaricus blazei Murrill exerts anti-tumor activity against leukemic cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1800, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.S.; Duan, Y.; Li, Z.C.; Gao, J.M.; Qi, J.; Liu, C. The alkynyl-containing compounds from mushrooms and their biological activities. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2023, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.S.; Kaur, H.P.; Kanwar, J.R. Mushroom lectins as promising anticancer substances. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2016, 17, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayeka, P.A. Potential of mushroom compounds as immunomodulators in cancer immunotherapy: A review. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 7271509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, V.; Pourianfar, H.R.; Mohammadnejad, S.; Madjid Ansari, A.; Farahmand, L. Anticancer potentiality and mode of action of low-carbohydrate proteins and peptides from mushrooms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 6855–6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Li, P.; Luo, Q.; Phan, C.W.; Li, Q.; Jin, X.; Huang, W. Induction of apoptosis in HeLa cells by a novel peptide from fruiting bodies of Morchella importuna via the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 5563367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittayakhajonwut, P.; Dramae, A.; Intaraudom, C.; Boonyuen, N.; Nithithanasilp, S.; Rachtawee, P.; Laksanacharoen, P. Two new drimane sesquiterpenes, fudecadiones A and B, from the soil fungus Penicillium sp. BCC 17468. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, X.; Tian, D.; Wei, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Ding, W.; Wu, B.; Tang, J. New drimane sesquiterpenes and polyketides from marine-derived fungus Penicillium sp. TW58-16 and their anti-inflammatory and α-glucosidase inhibitory effects. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiek, M.; Williams, J.; Schmich, K.; Hüttel, W.; Merfort, I.; Salomon, C.E.; Aldrich, C.C.; Hoffmeister, D. Structure and cytotoxicity of arnamial and related fungal sesquiterpene aryl esters. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1888–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-H.; Huang, H.-L.; Huang, W.-P.; Chen, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-J. Armillaridin induces autophagy-associated cell death in human chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 cells. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 14291–14300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.-W.; Chen, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-J. Therapeutic and radiosensitizing effects of armillaridin on human esophageal cancer cells. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 459271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.J.; Chen, C.C.; Huang, H.L. Induction of apoptosis by Armillaria mellea constituent armillarikin in human hepatocellular carcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 4773–4783. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.J.; Wu, S.Y.; Chen, C.C.; Tsao, Y.L.; Hsu, N.C.; Chou, Y.C.; Huang, H.L. Armillaria mellea component armillarikin induces apoptosis in human leukemia cells. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 6, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.X.; Liu, W.Z.; Chen, Y.C.; Sun, Z.H.; Tan, Y.Z.; Li, H.H.; Zhang, W.M. Cytotoxic trichothecene macrolides from the endophyte fungus Myrothecium roridum. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 18, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, M.C.; Taylor, H.L.; Wall, M.E.; Coggon, P.; McPhail, A.T. The isolation and structure of Taxol, a novel antileukemic and antitumor agent from Taxus brevifolia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 2325–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W.P.; Rowinsky, E.K.; Rosenshein, N.B.; Grumbine, F.C.; Ettinger, D.S.; Armstrong, D.K.; Donehower, R.C. Taxol: A unique antineoplastic agent with significant activity in advanced ovarian epithelial neoplasms. Ann. Intern. Med. 1989, 111, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, P.B.; Fant, J.; Horwitz, S.B. Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by Taxol. Nature 1979, 277, 665–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, B.A. How Taxol/paclitaxel kills cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 2677–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.P.H.; Horwitz, S.B. Taxol: The first microtubule stabilizing agent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McChesney, J.D.; Venkataraman, S.K.; Henri, J.T. Plant natural products: Back to the future or into extinction? Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 2015–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, H. Production of paclitaxel and the related taxanes by cell suspension cultures of Taxus species. Curr. Drug Targets 2006, 7, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, G.; Stierle, A.; Stierle, D.; Hess, W.M. Taxomyces andreanae, a proposed new taxon for a bulbilliferous hyphomycete associated with Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia). Mycotaxon 1993, 47, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subban, K.; Kempken, F. Insights into Taxol® biosynthesis by endophytic fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 6151–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, C.; Jennewein, S. Taxol® biosynthesis and production: From forests to fermenters. In Biotechnology of Natural Products; Schwab, W., Lange, B.M., Wüst, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 145–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran, R.S.; Kim, H.J.; Hur, B.K. Taxol-producing [corrected] fungal endophyte, Pestalotiopsis species isolated from Taxus cuspidata. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2010, 110, 541–546, Erratum in J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2011, 111, 731.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Singh, B.; Kumar, P.; Singh, B.; Thakur, V.; Thakur, A.; Thakur, N.; Pandey, D.; Duni, C. Hyper-production of Taxol from Aspergillus fumigatus, an endophytic fungus isolated from Taxus sp. of the Northern Himalayan region. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 24, e00395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, M.; Marudhamuthu, M. Hitherto unknown terpene synthase organization in Taxol-producing endophytic bacteria isolated from marine macroalgae. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinig, U.; Scholz, S.; Jennewein, S. Getting to the bottom of Taxol biosynthesis by fungi. Fungal Divers. 2013, 60, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefner, J.; Ketchum, R.E.B.; Croteau, R. Cloning and functional expression of a cDNA encoding geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase from Taxus canadensis and assessment of the role of this prenyltransferase in cells induced for Taxol production. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998, 98, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennewein, S.; Long, R.M.; Williams, R.M.; Croteau, R. Cytochrome P450 taxadiene 5 alpha-hydroxylase, a mechanistically unusual monooxygenase catalyzing the first oxygenation step of Taxol biosynthesis. Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClune, C.J.; Liu, J.C.-T.; Wick, C.; Peña, R.; Lange, B.M.; Fordyce, P.M.; Sattely, E.S. Discovery of FoTO1 and Taxol genes enables biosynthesis of baccatin III. Nature 2025, 643, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, F.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Motawia, M.S.; Kampranis, S.C. Elucidation of the final steps in Taxol biosynthesis and its biotechnological production. Nat. Synth. 2025, 4, 1212–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.F.; Liras, P. Comparative molecular mechanisms of biosynthesis of naringenin and related chalcones in actinobacteria and plants: Relevance for the obtention of potent bioactive metabolites. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Park, J.G.; Ali, M.S.; Choi, S.J.; Baek, K.H. Systematic analysis of the anticancer agent Taxol-producing capacity in Colletotrichum species and use of the species for Taxol production. Mycobiology 2016, 44, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, H.F.; Araújo, L.C.A.; Santos, B.S.D.; Paiva, P.M.G.; Napoleão, T.H.; Correia, M.T.D.S.; Oliveira, M.B.M.; Lima, G.M.S.; Ximenes, R.M.; Silva, T.D.D.; et al. Screening of endophytic fungi stored in a culture collection for Taxol production. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2018, 49, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Barrero, R.A.; Zhang, B.; Sun, G.; Wilson, I.W.; Xie, F.; Walker, K.D.; Parks, J.W.; Bruce, R.; et al. Genome sequencing and analysis of the paclitaxel-producing endophytic fungus Penicillium aurantiogriseum NRRL 62431. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimmino, A.; Mathieu, V.; Masi, M.; Baroncelli, R.; Boari, A.; Pescitelli, G.; Ferderin, M.; Lisy, R.; Evidente, M.; Tuzi, A.; et al. Higginsianins A and B, two diterpenoid α-pyrones produced by Colletotrichum higginsianum, with in vitro cytostatic activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangermano, F.; Masi, M.; Vivo, M.; Ravindra, P.; Cimmino, A.; Pollice, A.; Evidente, A.; Calabrò, V. Higginsianins A and B, two fungal diterpenoid α-pyrones with cytotoxic activity against human cancer cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 2019, 61, 104614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkel, G.; Anke, T. Products from basidiomycetes. In Biotechnology; Kleinkauf, H., von Döhren, H., Eds.; VCH Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 1997; Volume 7, pp. 489–533. [Google Scholar]

- Lingham, R.B.; Silverman, K.C.; Jayasuriya, H.; Kim, B.M.; Amo, S.E.; Wilson, F.R.; Rew, D.J.; Schaber, M.D.; Bergstrom, J.D.; Koblan, K.S.; et al. Clavaric acid and steroidal analogues as Ras- and FPP-directed inhibitors of human farnesyl-protein transferase. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 4492–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasuriya, H.; Silverman, K.C.; Zink, D.L.; Jenkins, R.G.; Sánchez, M.; Pelaez, F.; Vilella, D.; Lingham, R.B.; Singh, S.B. Clavaric acid: A triterpenoid inhibitor of farnesyl-protein transferase from Clavariadelphus truncatus. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 1568–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbacid, M. Ras genes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1987, 56, 779–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.R.; Kim, K.M.; Jeon, B.H.; Choi, S. The hexane fraction of Naematoloma sublateritium extract suppresses the TNF-alpha-induced metastatic potential of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through modulation of the JNK and p38 pathways. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.R.; Kim, K.M.; Jeon, B.H.; Choi, J.W.; Choi, S. The butanol fraction of Naematoloma sublateritium suppresses the inflammatory response through downregulation of NF-kappaB in human endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 29, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ványolós, A.; Muszyńska, B.; Chuluunbaatar, B.; Gdula-Argasińska, J.; Kała, K.; Hohmann, J. Extracts and steroids from the edible mushroom Hypholoma lateritium exhibit anti-inflammatory properties by inhibition of COX-2 and activation of Nrf2. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e2000391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godio, R.P.; Fouces, R.; Martín, J.F. A squalene epoxidase is involved in biosynthesis of both the antitumor compound clavaric acid and sterols in the basidiomycete H. sublateritium. Chem. Biol. 2007, 14, 1334–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoza, R.E.; Vizcaíno, J.A.; Hermosa, M.R.; Sousa, S.; González, F.J.; Llobell, A.; Monte, E.; Gutiérrez, S. Cloning and characterization of the erg1 gene of Trichoderma harzianum: Effect of the erg1 silencing on ergosterol biosynthesis and resistance to terbinafine. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2006, 43, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, I.; Prestwich, G.D. Squalene epoxidase and oxidosqualene: Lanosterol cyclase; key enzymes in cholesterol biosynthesis. In Comprehensive Natural Products Chemistry; Barton, D.H.R., Nakanishi, K., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 1999; Volume 2, pp. 267–298. [Google Scholar]

- Godio, R.P.; Martín, J.F. Modified oxidosqualene cyclases in the formation of bioactive secondary metabolites: Biosynthesis of the antitumor clavaric acid. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2009, 46, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, R.; Schulz-Gasch, T.; D’Arcy, B.; Benz, J.; Aebi, J.; Dehmlow, H.; Hennig, M.; Stihle, M.; Ruf, A. Insight into steroid scaffold formation from the structure of human oxidosqualene cyclase. Nature 2004, 432, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwede, T.; Kopp, J.; Guex, N.; Peitsch, M.C. SWISS-MODEL: An automated protein homology modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3381–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, B.; Osbourn, A.E. Metabolic diversification-independent assembly of operon-like gene clusters in different plants. Science 2008, 320, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steussy, C.N.; Vartia, A.A.; Burgner, J.W.; Sutherlin, A.; Rodwell, V.W.; Stauffacher, C.V. X-ray crystal structures of HMG-CoA synthase from Enterococcus faecalis and a complex with its second substrate/inhibitor acetoacetyl-CoA. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 14256–14267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojer, F.; Ferrer, J.L.; Richard, S.B.; Nagegowda, D.A.; Chye, M.-L.; Bach, T.J.; Noel, J.P. Structural basis for the design of potent and species-specific inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11491–11496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miziorko, H.M. Enzymes of the mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011, 505, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Huang, O.; Dong, Q.; Li, D.; Ding, S.; Ma, F.; Yu, H. Genomic comparative analysis of Cordyceps pseudotenuipes with other species from Cordyceps. Metabolites 2022, 12, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martirena-Ramírez, A.; Serrano-Gamboa, J.G.; Pérez-Llano, Y.; Zenteno-Alegría, C.O.; Iza-Arteaga, M.L.; Del Rayo Sánchez-Carbente, M.; Fernández-Ocaña, A.M.; Batista-García, R.A.; Folch-Mallol, J.L. Aspergillus brasiliensis E_15.1: A novel thermophilic endophyte from a volcanic crater unveiled through comprehensive genome-wide, phenotypic analysis, and plant growth-promoting trails. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, X. Comparative genomic data provide new insight on the evolution of pathogenicity in Sporothrix species. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 565439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, A.K.; Condron, L.; O’Callaghan, M.; Waipara, N.; Black, A. Whole genome sequencing of Penicillium and Burkholderia strains antagonistic to the causal agent of kauri dieback disease (Phytophthora agathidicida) reveals biosynthetic gene clusters related to antimicrobial secondary metabolites. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2025, 25, e13810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Jia, G.; Sun, H.; Sun, T.; Hou, D. Genome sequence of the fungus Pycnoporus sanguineus, which produces cinnabarinic acid and pH- and thermo-stable laccases. Gene 2020, 742, 144586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Li, H.; Qi, J.; Chen, C.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y. Genome mining of secondary metabolites from a marine-derived Aspergillus terreus B12. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 5621–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.H.; Liu, J.W.; Zhong, J.J. Ganoderic acid Me inhibits tumor invasion through down-regulating matrix metalloproteinases 2/9 gene expression. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2008, 108, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.F.; Wahab, S.; Ahmad, F.A.; Ashraf, S.A.; Abullais, S.S.; Saas, H.H. Ganoderma lucidum: A potential pleiotropic approach of ganoderic acids in health reinforcement and factors influencing their production. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2022, 39, 100–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; You, H.; Xu, J.-W. Enhancement of ganoderic acid production by promoting sporulation in a liquid static culture of Ganoderma species. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 328, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.W.; Xu, Y.N.; Zhong, J.J. Production of individual ganoderic acids and expression of biosynthetic genes in liquid static and shaking cultures of Ganoderma lucidum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.L.; Xu, J.; Liu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Nelson, D.R.; Zhou, S.G.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.; Sun, Y.; et al. Genome sequence of the model medicinal mushroom Ganoderma lucidum. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, A.; Acharya, K. Mushrooms: An emerging resource for therapeutic terpenoids. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Qiao, X.; Ye, M. Terpenoids from the medicinal mushroom Antrodia camphorata: Chemistry and medicinal potential. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2021, 38, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, Y.; Abe, I. Meroterpenoids. In Biosynthesis and Molecular Genetics of Fungal Secondary Metabolites; Martín, J.F., García-Estrada, C., Zeilinger, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Omura, S.; Inokoshi, J.; Uchida, R.; Shiomi, K.; Masuma, R.; Kawakubo, R.; Tanaka, H.; Iwai, Y.; Kosemura, S.; Yamamura, S. Andrastins A–C, new protein farnesyltransferase inhibitors produced by Penicillium sp. FO-3929. I. Producing strain, fermentation, isolation, and biological. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 1265–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, R.; Shiomi, K.; Inokoshi, J.; Sunazuka, T.; Tanaka, H.; Iwai, Y.; Takayanagi, H.; Omura, S. Andrastins A–C, new protein farnesyltransferase inhibitors produced by Penicillium sp. FO-3929. II. Structure elucidation and biosynthesis. J. Antibiot. 1996, 49, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, R.; Shiomi, K.; Inokoshi, J.; Tanaka, H.; Iwai, Y.; Omura, S. Andrastin D, novel protein farnesyltransferase inhibitor produced by Penicillium sp. FO-3929. J. Antibiot. 1996, 49, 1278–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bodega, M.A.; Mauriz, E.; Gómez, A.; Martín, J.F. Proteolytic activity, mycotoxins and andrastin A in Penicillium roqueforti strains isolated from Cabrales, Valdeón and Bejes-Tresviso local varieties of blue-veined cheeses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 136, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.F.; Dalsgaard, P.W.; Smedsgaard, J.; Larsen, T.O. Andrastins A–D, Penicillium roqueforti metabolites consistently produced in blue-mold ripened cheese. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2908–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Estrada, C.; Martín, J.F. Biosynthetic gene clusters for relevant secondary metabolites produced by Penicillium roqueforti in blue cheeses. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 8303–8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rho, M.C.; Toyoshima, M.; Hayashi, M.; Uchida, R.; Shiomi, K.; Komiyama, K.; Omura, S. Enhancement of drug accumulation by andrastin A produced by Penicillium sp. FO-3929 in vincristine-resistant KB cells. J. Antibiot. 1998, 51, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Feng, T.; Li, Z.H.; Dong, Z.J.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.K. Highly oxygenated meroterpenoids from fruiting bodies of the mushroom Tricholoma terreum. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1365–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinokurova, N.G.; Ivanushkina, N.E.; Kochkina, G.A.; Arinbasarov, M.U.; Ozerskaia, S.M. Production of mycophenolic acid by fungi of the genus Penicillium Link. Prikl. Biokhim. Mikrobiol. 2005, 41, 95–98. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dun, B.; Xu, H.; Sharma, A.; Liu, H.; Yu, H.; Yi, B.; Liu, X.; He, M.; Zeng, L.; She, J.X. Delineation of biological and molecular mechanisms underlying the diverse anticancer activities of mycophenolic acid. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2013, 6, 2880–2886. [Google Scholar]

- Stierle, D.B.; Stierle, A.A.; Hobbs, J.D.; Stokken, J.; Clardy, J. Berkeleydione and berkeleytrione, new bioactive metabolites from an acid mine organism. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M.; Andolfi, A.; Mathieu, V.; Boari, A.; Cimmino, A.; Banuls, L.M.Y.; Vurro, M.; Kornienko, A.; Kiss, R.; Evidente, A. Fischerindoline, a pyrroloindole sesquiterpenoid isolated from Neosartorya pseudofischeri, with in vitro growth inhibitory activity in human cancer cell lines. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 7466–7470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, Y.; Awakawa, T.; Abe, I. Reconstituted biosynthesis of fungal meroterpenoid andrastin A. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 8199–8204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeseman, K.; Ropars, J.; Renault, P.; Dupont, J.; Gouzy, J.; Branca, A.; Abraham, A.L.; Ceppi, M.; Conseiller, E.; Debuchy, R.; et al. Multiple recent horizontal transfers of a large genomic region in cheese making fungi. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Aedo, J.F.; Gil-Durán, C.; Del-Cid, A.; Valdés, N.; Álamos, P.; Vaca, I.; García-Rico, R.O.; Levicán, G.; Tello, M.; Chávez, R. The biosynthetic gene cluster for andrastin A in Penicillium roqueforti. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.F.; Coton, M. Blue cheese: Microbiota and fungal metabolites. In Fermented Foods in Health and Disease Prevention; Frias, J., Martínez-Villaluenga, C., Peñas, E., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Chanda, A.; Roze, A.L.V.; Kang, S.; Artymovich, K.; Hicks, G.R.; Raikhel, N.V.; Calvo, A.M.; Linz, J.E. A key role for vesicles in fungal secondary metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19533–19538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skellam, E. Subcellular localization of fungal specialized metabolites. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2022, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chávez, R.; Vaca, I.; García-Estrada, C. Secondary metabolites produced by the blue-cheese ripening mold Penicillium roqueforti: Biosynthesis and regulation mechanisms. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palkina, K.A.; Ipatova, D.A.; Shakhova, E.S.; Balakireva, A.V.; Markina, N.M. Therapeutic potential of hispidin-fungal and plant polyketide. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.H.; Lee, Y.M.; Park, S.R.; Kim, D.H.; Lim, B.O. Anticancer activity of hispidin via reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 4087–4093. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, A.; Liang, X.; Zhu, S.; Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Song, L. Chlorogenic acid induces apoptosis, inhibits metastasis and improves antitumor immunity in breast cancer via the NF-κB signaling pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 45, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Jin, Q.; Yu, T.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y. Phellinus gilvus-derived protocatechualdehyde induces G0/G1 phase arrest and apoptosis in murine B16-F10 cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 21, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Jiang, X.; Jeong, J.B.; Lee, S.H. Anticancer activity of protocatechualdehyde in human breast cancer cells. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.B.; Lee, S.H. Protocatechualdehyde possesses anti-cancer activity through downregulating cyclin D1 and HDAC2 in human colorectal cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 430, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xiong, M.; Yang, X.; Yao, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.A.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Lv, J. Six new polyphenolic metabolites isolated from the Suillus granulatus and their cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1390256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura, S.; Tomoda, H.; Kimura, K.; Zhen, D.Z.; Kumagai, H.; Igarashi, K.; Imamura, N.; Takahashi, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Iwai, Y. Atpenins, new antifungal antibiotics produced by Penicillium sp. Production, isolation, physico-chemical and biological properties. J. Antibiot. 1988, 41, 1769–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawada, M.; Momose, I.; Someno, T.; Tsujiuchi, G.; Ikeda, D. New atpenins, NBRI23477 A and B, inhibit the growth of human prostate cancer cells. J. Antibiot. 2009, 62, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Gupta, R.; Chandran, R.R.; Divekar, P.V. Botryodiplodin—A new antibiotic from Botryodiplodia theobromae. II. Production, isolation and biological properties. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 1966, 4, 152–153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Renauld, F.; Moreau, S.; Lablachecombier, A.; Tiffon, B. Botryodiplodin, a mycotoxin from Penicillium roqueforti. Reaction with amino-pyrimidines, amino-purines and 2-deoxynucleosides. Tetrahedron 1985, 41, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, M.M.; Félix, C.; Lima, F.; Ferreira, V.; Naviglio, D.; Salvatore, F.; Duarte, A.S.; Alves, A.; Andolfi, A.; Esteves, A.C. Secondary metabolites produced by Macrophomina phaseolina isolated from Eucalyptus globulus. Agriculture 2020, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuska, J.; Fuskova, A. The in vitro-in vivo effect of antibiotic PSX-1 on lympholeukaemia L-5178. J. Antibiot. 1976, 29, 981–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittakoop, P.; Punya, J.; Kongsaeree, P.; Lertwerawat, Y.; Jintasirikul, A.; Tanticharoen, M.; Thebtaranonth, Y. Bioactive naphthoquinones from Cordyceps unilateralis. Phytochemistry 1999, 52, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ding, R.; Gao, H.; Guo, L.; Yao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, J. New spirobisnaphthalenes from an endolichenic fungus strain CGMCC 3.15192 and their anticancer effects through the P53-P21 pathway. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 39082–39089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, I.; Kim, M.; Wood, W.F.; Naoki, H. Clitocine, a new insecticidal nucleoside from the mushroom Clitocybe inversa. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986, 27, 4277–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhao, Y.P.; Yang, L.; Fu, C.X. Anti-proliferative effect of clitocine from the mushroom Leucopaxillus giganteus on human cervical cancer HeLa cells by inducing apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2008, 262, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez Ghoran, S.; Taktaz, F.; Ayatollahi, S.A.; Kijjoa, A. Anthraquinones and their analogues from marine-derived fungi: Chemistry and biological activities. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, I.; Torres-Vargas, J.A.; Sánchez, J.M.; Trigal, M.; García-Caballero, M.; Medina, M.Á.; Quesada, A.R. Danthron, an anthraquinone isolated from a marine fungus, is a new inhibitor of angiogenesis exhibiting interesting antitumor and antioxidant properties. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Zhu, T.; Fang, Y.; Liu, H.; Gu, Q.; Zhu, W. Aspergiolide A, a novel anthraquinone derivative with naphtho[1,2,3-de]chromene-2,7-dione skeleton isolated from a marine-derived fungus Aspergillus glaucus. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 1085–1088, Correction in Tetrahedron 2008, 63, 4657.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qi, X.; Li, D.; Zhu, T.; Mo, X.; Li, J. Anticancer efficacy and absorption, distribution, metabolism, and toxicity studies of aspergiolide A in early drug development. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2014, 8, 1965–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, R.; Dalvi, Y.B.; Lamrood, P.Y.; Shinde, B.P.; Nair, C.K.K. Historical and current perspectives on therapeutic potential of higher basidiomycetes: An overview. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sausville, E.A.; Duncan, K.L.; Senderowicz, A.; Plowman, J.; Randazzo, P.A.; Kahn, R.; Malspeis, L.; Grever, M.R. Antiproliferative effect in vitro and antitumor activity in vivo of brefeldin A. Cancer J. Sci. Am. 1996, 2, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vigushin, D.M.; Mirsaidi, N.; Brooke, G.; Sun, C.; Pace, P.; Inman, L.; Moody, C.J.; Coombes, R.C. Gliotoxin is a dual inhibitor of farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase I with antitumor activity against breast cancer in vivo. Med. Oncol. 2004, 21, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, C.; Rosenberg, M.; Vail, D.M. A review of paclitaxel and novel formulations including those suitable for use in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2015, 29, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L.R.; Supko, J.G.; Malspeis, L. Analysis of brefeldin A in plasma by gas chromatography with electron capture detection. Anal. Biochem. 1993, 211, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L.R.; Wolfe, T.L.; Malspeis, L.; Supko, J.G. Analysis of brefeldin A and the prodrug breflate in plasma by gas chromatography with mass selective detection. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1998, 16, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, X.; Qu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Pan, H.; Li, H.; Hua, H.; Li, D. Design and synthesis of Brefeldin A-Isothiocyanate derivatives with selectivity and their potential for cervical cancer therapy. Molecules 2023, 28, 4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, S.M. Recent synthesis and discovery of brefeldin A analogs. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.X.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Wu, Y.W.; Chen, G.Y.; Shao, C.L.; Gu, Y.C.; Liu, M.; Wei, M.Y. Semi-synthesis, cytotoxic evaluation, and structure-activity relationships of brefeldin A derivatives with antileukemia activity. Mar. Drugs 2021, 20, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garimella, T.S.; Ross, D.D.; Eiseman, J.L.; Mondick, J.T.; Joseph, E.; Nakanishi, T.; Bates, S.E.; Bauer, K.S. Plasma pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) inhibitor fumitremorgin C in SCID mice bearing T8 tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2005, 55, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, M.; Suzuki, S.; Ozaki, N. Biochemical investigation on the abnormal behaviors induced by fumitremorgin A, a tremorgenic mycotoxin to mice. J. Pharmacobiodyn. 1983, 6, 748–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.D.; van Loevezijn, A.; Lakhai, J.M.; van der Valk, M.; van Tellingen, O.; Reid, G.; Schellens, J.H.; Koomen, G.J.; Schinkel, A.H. Potent and specific inhibition of the breast cancer resistance protein multidrug transporter in vitro and in mouse intestine by a novel analogue of fumitremorgin C. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002, 1, 417–425. [Google Scholar]

- Chandratre, S.; Olsen, J.; Howley, R.; Chen, B. Targeting ABCG2 transporter to enhance 5-aminolevulinic acid for tumor visualization and photodynamic therapy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 217, 115851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Lei, S.; Lu, J.; Hao, Y.; Qian, Q.; Devanathan, A.S.; Feng, Z.; Xie, X.Q.; Wipf, P.; Ma, X. Metabolism-guided development of Ko143 analogs as ABCG2 inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 259, 115666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, P.; Newcombe, N.R.; Waring, P.; Müllbacher, A. In vivo immunosuppressive activity of gliotoxin, a metabolite produced by human pathogenic fungi. Infect. Immun. 1994, 62, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagens, W.I.; Olinga, P.; Meijer, D.K.; Groothuis, G.M.; Beljaars, L.; Poelstra, K. Gliotoxin non-selectively induces apoptosis in fibrotic and normal livers. Liver Int. 2006, 26, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, J.W.; Chung, D.; Balajee, S.A.; Marr, K.A.; Andes, D.; Nielsen, K.F.; Frisvad, J.C.; Kirby, K.A.; Keller, N.P. GliZ, a transcriptional regulator of gliotoxin biosynthesis, contributes to Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 6761–6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.D.; Calvo, A.M. The mtfA transcription factor gene controls morphogenesis, gliotoxin production, and virulence in the opportunistic human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot. Cell 2014, 13, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Song, H. Progress in gliotoxin research. Molecules 2025, 30, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Develoux, M. Griséofulvine [Griseofulvin]. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2001, 128, 1317–1325. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Knasmüller, S.; Parzefall, W.; Helma, C.; Kassie, F.; Ecker, S.; Schulte-Hermann, R. Toxic effects of griseofulvin: Disease models, mechanisms, and risk assessment. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1997, 27, 495–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saykhedkar, S.S.; Singhal, R.S. Solid-state fermentation for production of griseofulvin on rice bran using Penicillium griseofulvum. Biotechnol. Prog. 2004, 20, 1280–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Di, L.; Cheng, X.; Ji, W.; Piao, H.; Cheng, G.; Zou, M. The characteristics and mechanism of co-administration of lovastatin solid dispersion with kaempferol to increase oral bioavailability. Xenobiotica 2020, 50, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.S.; Gerson, R.J.; Kornbrust, D.J.; Kloss, M.W.; Prahalada, S.; Berry, P.H.; Alberts, A.W.; Bokelman, D.L. Preclinical evaluation of lovastatin. Am. J. Cardiol. 1988, 62, 16J–27J. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornbrust, D.J.; MacDonald, J.S.; Peter, C.P.; Duchai, D.M.; Stubbs, R.J.; Germershausen, J.I.; Alberts, A.W. Toxicity of the HMG-coenzyme A reductase inhibitor, lovastatin, to rabbits. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989, 248, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, M.; Roizes, S.; von der Weid, P.Y. Off-target effect of lovastatin disrupts dietary lipid uptake and dissemination through pro-drug inhibition of the mesenteric lymphatic smooth muscle cell contractile apparatus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, K.C.; Mulinari, F.; Franco, O.L.; Soares, M.S.; Magalhães, B.S.; Parachin, N.S. Lovastatin production: From molecular basis to industrial process optimization. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 648–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.; Abd Rahim, M.H.; Campbell, L.; Carter, D.; Abbas, A.; Montoya, A. Increasing lovastatin production by re-routing the precursors flow of Aspergillus terreus via metabolic engineering. Mol. Biotechnol. 2022, 64, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnichsen, D.S.; Relling, M.V. Clinical pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1994, 27, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, T.; Igarashi, T.; Sato, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Ohtani, H.; Kato, Y. Toxicity studies of paclitaxel (I): Single intravenous dose toxicity study in rats. J. Toxicol. Sci. 1994, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, T.; Igarashi, T.; Sato, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Ohtani, H.; Kato, Y. Toxicity studies of paclitaxel (II): One-month intermittent intravenous toxicity study in rats. J. Toxicol. Sci. 1994, 19, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.C.; Victorino, V.J.; Martins-Pinge, M.C.; Cecchini, A.L.; Panis, C.; Cecchini, R. Systemic toxicity induced by paclitaxel in vivo is associated with the solvent cremophor EL through oxidative stress-driven mechanisms. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 68, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Li, F.; Xie, L.; Gu, M.; Li, C.; Liu, C.; Peng, C.; Li, W. Design and synthesis of novel phenylahistin derivatives based on co-crystal structures as potent microtubule inhibitors for anti-cancer therapy. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Chemical Class | Producing Fungi | Antitumor Activity/ Preclinical and Clinical Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andrastin A | Meroterpenoid | P. chrysogenum | RAS-prenyltransferase inhibitor. It blocks the efflux of anticancer drugs/ Preclinical stage (in vitro studies) [238,239,241] |

| P. roqueforti | |||

| Asperpyrone A/B | Dimeric naphthopyrones (aromatic PK) | Aspergillus sp. XNM-4 | Cytotoxic to SK-OV-3 and PANC-1/ Preclinical stage (in vitro studies) [74] |

| Brefeldin A | Macrolide PK | Paecilomyces, Alternaria, Curvularia, Penicillium, Phyllosticta | Cytotoxic to HL-60, KB, HeLa, MCF-7, Spc-A1. It disrupts Golgi function/ Preclinical stage (in vivo study with subcutaneous and subrenal capsule melanoma mouse models) [75,76,77,78,278] |

| Clavaric Acid | Triterpene | H. sublateritium | RAS-prenyltransferase inhibitor; anti-metastatic activity/ Preclinical stage (in vitro studies) [207,208,209] |

| Fumitremorgin C | DKP alkaloid | A. fumigatus | Selective BCRP/ABCG2 inhibitor (overcomes multidrug resistance)/ Preclinical stage (in vitro studies) [119] |

| Gliotoxin | DKP alkaloid | A. fumigatus, N. pseudofischeri, T. virens, D. cejpiii | Highly active across breast, colorectal, leukemia, lung cell lines. Potent apoptosis induction via mitochondrial pathway activation of Bax, caspases, and cytochrome c release/ Preclinical stage (in vivo study with rat mammary carcinoma model [134,135,136,279] |

| Griseofulvin | Chlorinated PK | P. griseofulvum and other ascomycetes | Broad antitumor activity: breast, lung, colorectal, cervical cancers. Microtubule inhibition, mitotic arrest/ Approved as antifungal drug, but not established as chemotherapy. Preclinical stage (in vivo studies with nude mouse xenograft models of small-cell lung cancer) [84,85,86] |

| Lovastatin | PK | A. terreus, P. citrinum, M. ruber | Anticancer activity across many tumors. It enhances chemotherapy responses. Apoptosis induction, cell-cycle arrest, angiogenesis inhibition/ Approved as a lipid-lowering drug. Preclinical in vitro and in vivo evidence for anticancer effects and preclinical and clinical/epidemiological evidence of synergy with other drugs, but not approved for cancer treatment [70,72] |

| Paclitaxel (Taxol®) | Diterpene | Endophytic fungi (e.g., T. andreanae) | Microtubule-stabilizing agent that blocks mitosis/ Clinically approved anticancer drug [280] |

| Phenylahistin | DKP alkaloid | A. ustus | Tubulin inhibitor; strong cytotoxic activity/ Parent of clinical candidate plinabulin (Phase III study in prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia) [110,111,112,113,114,115] |

| Compound | ADME Studies | In Vivo Toxicity | Production/ Improvement Prospects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andrastin A | Not available | Not reported | Low yield/ Heterologous production of andrastin A by the expression of the biosynthetic gene cluster in A. oryzae [249] |

| Asperpyrone A/B | Not available | Not reported | Low yield/ Not reported |