Potential Biomarker and Therapeutic Tools for Pathological Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure: Extracellular Vesicles

Abstract

1. Introduction

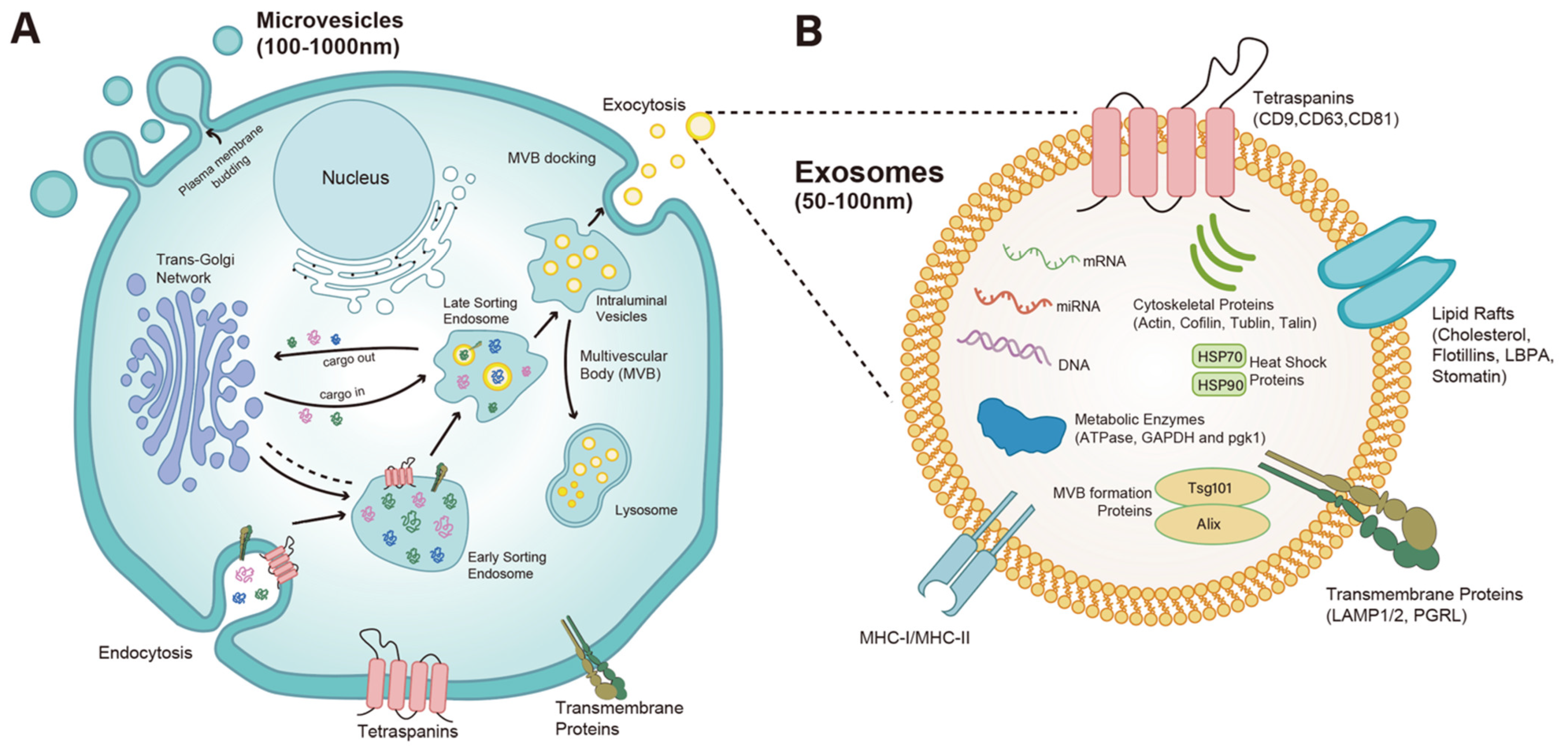

2. Biogenesis and Function of EVs and Exosomes

3. Cardiac Hypertrophy and HF

4. Circulating EVs as Biomarkers for Cardiac Hypertrophy and HF

4.1. Acute Myocardial Infarction Associated HF

4.2. Peripartum Cardiomyopathy Associated HF

4.3. Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease-Associated HF

4.4. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy-Associated HF

4.5. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM)-Associated HF

4.6. EVs in Other Etiologies of HF

5. Role of EVs in Cardiac Hypertrophy and HF

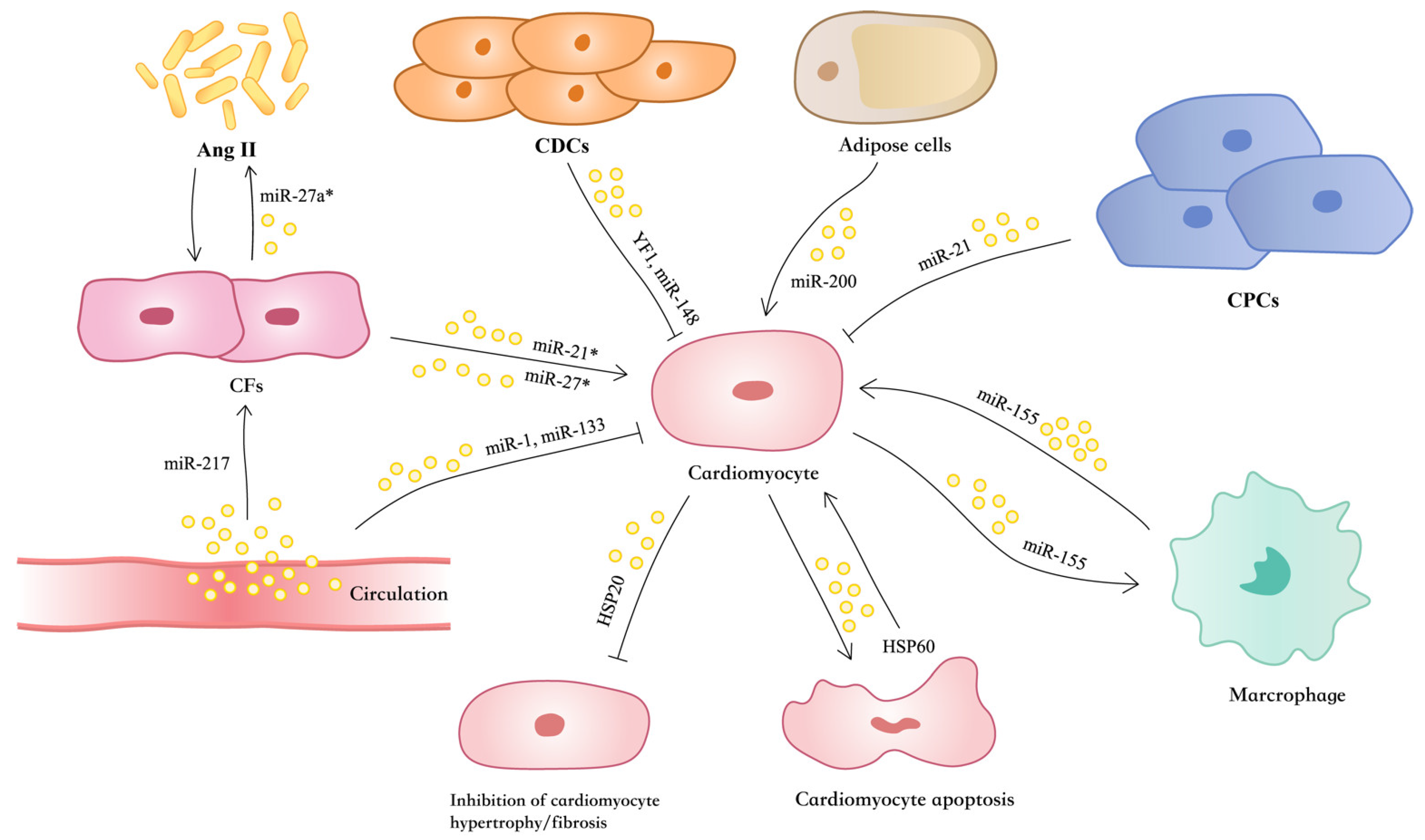

5.1. EVs Mediate Cardiac Hypertrophy Under Pathological Hypertrophic Stresses

5.2. EVs Regulate Cardiac Inflammation and Hypertrophy

5.3. EVs Regulate Reactive Oxygen Species, Oxidative Stress, and Cardiac Hypertrophy

5.4. EVs Mediate Heat-Shock-Protein Transport and Cardiac Hypertrophy

5.5. EVs Regulate Sympathetic Activity and HF

5.6. EVs Mediate Reciprocal Regulation Between Cardiomyocytes and Fibroblasts in Cardiac Hypertrophy and HF

5.7. EVs Mediate Adipose Regulation of Cardiac Hypertrophy and HF

6. EV-Based Therapeutic Approaches for Cardiac Hypertrophy and HF

6.1. EVs from Stem Cells

6.2. EVs from CPCs and CDCs

6.3. EVs from Endothelial Progenitor Cells

6.4. EVs from MSCs

6.5. Other Kinds of EVs

6.6. Engineering Strategies and Clinical Translation of EV-Based Therapeutics

7. Conclusions and Prospect

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, M.; Sadoshima, J. Mechanisms of physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niel, G.; Carter, D.R.F.; Clayton, A.; Lambert, D.W.; Raposo, G.; Vader, P. Challenges and directions in studying cell-cell communication by extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, L.; Reiter, R.J.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Ren, J. Extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular diseases: From pathophysiology to diagnosis and therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2023, 74, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wu, Y.; Chen, C. Extracellular Vesicles as Emerging Regulators in Ischemic and Hypertrophic Cardiovascular Diseases: A Review of Pathogenesis and Therapeutics. Med. Sci. Monit. 2025, 31, e948948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerricchio, L.; Barile, L.; Bollini, S. Evolving Strategies for Extracellular Vesicles as Future Cardiac Therapeutics: From Macro- to Nano-Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z. Extracellular vesicular microRNAs and cardiac hypertrophy. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1444940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404, Erratum in J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.A.; Baba, S.K.; Sadida, H.Q.; Marzooqi, S.A.; Jerobin, J.; Altemani, F.H.; Algehainy, N.; Alanazi, M.A.; Abou-Samra, A.B.; Kumar, R.; et al. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trams, E.G.; Lauter, C.J.; Salem, N., Jr.; Heine, U. Exfoliation of membrane ecto-enzymes in the form of micro-vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1981, 645, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.T.; Johnstone, R.M. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: Selective externalization of the receptor. Cell 1983, 33, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkovic, K.; Hsu, C.; Chiantia, S.; Rajendran, L.; Wenzel, D.; Wieland, F.; Schwille, P.; Brügger, B.; Simons, M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science 2008, 319, 1244–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Raposo, G.; Thery, C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henne, W.M.; Stenmark, H.; Emr, S.D. Molecular mechanisms of the membrane sculpting ESCRT pathway. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a016766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, M.; Moita, C.; van Niel, G.; Kowal, J.; Vigneron, J.; Benaroch, P.; Manel, N.; Moita, L.F.; Thery, C.; Raposo, G. Analysis of ESCRT functions in exosome biogenesis, composition and secretion highlights the heterogeneity of extracellular vesicles. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 5553–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajimoto, T.; Okada, T.; Miya, S.; Zhang, L.; Nakamura, S. Ongoing activation of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors mediates maturation of exosomal multivesicular endosomes. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, J.H. ESCRTs are everywhere. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 2398–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gassart, A.; Geminard, C.; Fevrier, B.; Raposo, G.; Vidal, M. Lipid raft-associated protein sorting in exosomes. Blood 2003, 102, 4336–4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Zoller, M. Exosome target cell selection and the importance of exosomal tetraspanins: A hypothesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, D.J.; Franklin, J.L.; Dou, Y.; Liu, Q.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Demory Beckler, M.; Weaver, A.M.; Vickers, K.; Prasad, N.; Levy, S.; et al. KRAS-dependent sorting of miRNA to exosomes. Elife 2015, 4, e07197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Bi, J.; Huang, J.; Tang, Y.; Du, S.; Li, P. Exosome: A Review of Its Classification, Isolation Techniques, Storage, Diagnostic and Targeted Therapy Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 6917–6934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, L.M.; Wang, M.Z. Overview of Extracellular Vesicles, Their Origin, Composition, Purpose, and Methods for Exosome Isolation and Analysis. Cells 2019, 8, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschuschke, M.; Kocherova, I.; Bryja, A.; Mozdziak, P.; Angelova Volponi, A.; Janowicz, K.; Sibiak, R.; Piotrowska-Kempisty, H.; Izycki, D.; Bukowska, D.; et al. Inclusion Biogenesis, Methods of Isolation and Clinical Application of Human Cellular Exosomes. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klumperman, J.; Raposo, G. The complex ultrastructure of the endolysosomal system. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a016857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Morohashi, Y.; Yoshimura, S.; Manrique-Hoyos, N.; Jung, S.; Lauterbach, M.A.; Bakhti, M.; Gronborg, M.; Mobius, W.; Rhee, J.; et al. Regulation of exosome secretion by Rab35 and its GTPase-activating proteins TBC1D10A-C. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuffers, S.; Sem Wegner, C.; Stenmark, H.; Brech, A. Multivesicular endosome biogenesis in the absence of ESCRTs. Traffic 2009, 10, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcoran, C.; Friel, A.M.; Duffy, M.J.; Crown, J.; O’Driscoll, L. Intracellular and extracellular microRNAs in breast cancer. Clin. Chem. 2011, 57, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friel, A.M.; Corcoran, C.; Crown, J.; O’Driscoll, L. Relevance of circulating tumor cells, extracellular nucleic acids, and exosomes in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 123, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Anees, A.; Harsiddharay, R.K.; Kumar, P.; Tripathi, P.K. A Comprehensive Review on Exosome: Recent Progress and Outlook. Pharm. Nanotechnol. 2023, 12, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coumans, F.A.W.; Brisson, A.R.; Buzas, E.I.; Dignat-George, F.; Drees, E.E.E.; El-Andaloussi, S.; Emanueli, C.; Gasecka, A.; Hendrix, A.; Hill, A.F.; et al. Methodological Guidelines to Study Extracellular Vesicles. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 1632–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Yu, L.; Ma, T.; Xu, W.; Qian, H.; Sun, Y.; Shi, H. Small extracellular vesicles isolation and separation: Current techniques, pending questions and clinical applications. Theranostics 2022, 12, 6548–6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiapradja, A.; Chunduri, P.; Levick, S.P. The role of neuropeptides in adverse myocardial remodeling and heart failure. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 2019–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.R.; Jennings, G.L. Differences between pathological and physiological cardiac hypertrophy: Novel therapeutic strategies to treat heart failure. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2007, 34, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, B.C.; Weeks, K.L.; Pretorius, L.; McMullen, J.R. Molecular distinction between physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy: Experimental findings and therapeutic strategies. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 128, 191–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Yang, J.; Sun, J.; Qin, G. Extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular disease: Biological functions and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 233, 108025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Bohm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Celutkien, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 4–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marian, A.J.; Braunwald, E. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Genetics, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 749–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommen, S.R.; Semsarian, C. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A practical approach to guideline directed management. Lancet 2021, 398, 2102–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Song, L.; Wang, Z.; Ma, A.; Liu, T.; Gu, H.; Lu, S.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, L.; et al. Prevalence of idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in China: A population-based echocardiographic analysis of 8080 adults. Am. J. Med. 2004, 116, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, B.J.; Desai, M.Y.; Nishimura, R.A.; Spirito, P.; Rakowski, H.; Towbin, J.A.; Rowin, E.J.; Maron, M.S.; Sherrid, M.V. Diagnosis and Evaluation of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, B.J.; Spirito, P.; Roman, M.J.; Paranicas, M.; Okin, P.M.; Best, L.G.; Lee, E.T.; Devereux, R.B. Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a population-based sample of American Indians aged 51 to 77 years (the Strong Heart Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2004, 93, 1510–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, B.J.; Gardin, J.M.; Flack, J.M.; Gidding, S.S.; Kurosaki, T.T.; Bild, D.E. Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young adults. Echocardiographic analysis of 4111 subjects in the CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults. Circulation 1995, 92, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, H.G.; Lam, L.; Lokuge, A.; Krum, H.; Naughton, M.T.; De Villiers Smit, P.; Bystrzycki, A.; Eccleston, D.; Federman, J.; Flannery, G.; et al. B-type natriuretic peptide testing, clinical outcomes, and health services use in emergency department patients with dyspnea: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, e895–e1032, Erratum in Circulation 2023, 147, e674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Su, J.; Mende, U. Cross talk between cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts: From multiscale investigative approaches to mechanisms and functional consequences. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 303, H1385–H1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocco, P.; Montesanto, A.; La Grotta, R.; Paparazzo, E.; Soraci, L.; Dato, S.; Passarino, G.; Rose, G. The Potential Contribution of MyomiRs miR-133a-3p, -133b, and -206 Dysregulation in Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhou, H.; Tang, Q. miR-133: A Suppressor of Cardiac Remodeling? Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadi, H.; Ekstrom, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjostrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lotvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellingham, S.A.; Coleman, B.M.; Hill, A.F. Small RNA deep sequencing reveals a distinct miRNA signature released in exosomes from prion-infected neuronal cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 10937–10949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, N.; Rautou, P.E.; Tedgui, A.; Boulanger, C.M. Microparticles: Key protagonists in cardiovascular disorders. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2010, 36, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Hou, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, F.; Cheng, B.; Wang, W.; Lu, B.; Liu, P.; Lu, W.; et al. Exosomal let-7d-3p and miR-30d-5p as diagnostic biomarkers for non-invasive screening of cervical cancer and its precursors. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, D.; Tan, Y.; Guo, L.; Tang, A.; Zhao, Y. Identification of exosomal miRNA biomarkers for diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer by small RNA sequencing. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 182, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K.J.; Hennessy, E.J. Extracellular communication via microRNA: Lipid particles have a new message. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turchinovich, A.; Weiz, L.; Langheinz, A.; Burwinkel, B. Characterization of extracellular circulating microRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 7223–7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, Y.; Lu, D.; Bär, C.; Chatterjee, S.; Costa, A.; Riedel, I.; Mooren, F.C.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wei, M.; et al. miR-486 attenuates cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury and mediates the beneficial effect of exercise for myocardial protection. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 1675–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, L.; Moccetti, T.; Marbán, E.; Vassalli, G. Roles of exosomes in cardioprotection. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilyazova, I.; Asadullina, D.; Kagirova, E.; Sikka, R.; Mustafin, A.; Ivanova, E.; Bakhtiyarova, K.; Gilyazova, G.; Gupta, S.; Khusnutdinova, E.; et al. MiRNA-146a-A Key Player in Immunity and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, F.; Wang, R.; Saeed, Z.; Devaraj, S.; Masoor, K.; Nakshatri, H. Inflammation-associated microRNA changes in circulating exosomes of heart failure patients. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Chen, Y.C.; Du, Y.T.; Tao, J.; Li, W.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, Z. Circulating exosomal miR-92b-5p is a promising diagnostic biomarker of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients hospitalized for acute heart failure. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, M.A.; Skelly, D.A.; Dona, M.S.I.; Squiers, G.T.; Farrugia, G.E.; Gaynor, T.L.; Cohen, C.D.; Pandey, R.; Diep, H.; Vinh, A.; et al. High-Resolution Transcriptomic Profiling of the Heart During Chronic Stress Reveals Cellular Drivers of Cardiac Fibrosis and Hypertrophy. Circulation 2020, 142, 1448–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; López de Juan Abad, B.; Cheng, K. Cardiac fibrosis: Myofibroblast-mediated pathological regulation and drug delivery strategies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 173, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Xu, B.; Liu, Y.L.; Liu, Z. Reduced exosome miR-425 and miR-744 in the plasma represents the progression of fibrosis and heart failure. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, S.; Sakata, Y.; Suna, S.; Nakatani, D.; Usami, M.; Hara, M.; Kitamura, T.; Hamasaki, T.; Nanto, S.; Kawahara, Y.; et al. Circulating p53-responsive microRNAs are predictive indicators of heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, T.; Sugiyama, S.; Sugamura, K.; Ohba, K.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Konishi, M.; Matsubara, J.; Akiyama, E.; Sumida, H.; Matsui, K.; et al. Prognostic value of endothelial microparticles in patients with heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2010, 12, 1223–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezin, A.E.; Kremzer, A.A.; Martovitskaya, Y.V.; Samura, T.A.; Berezina, T.A. The predictive role of circulating microparticles in patients with chronic heart failure. BBA Clin. 2015, 3, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berezin, A.E.; Kremzer, A.A.; Samura, T.A.; Martovitskaya, Y.V.; Malinovskiy, Y.V.; Oleshko, S.V.; Berezina, T.A. Predictive value of apoptotic microparticles to mononuclear progenitor cells ratio in advanced chronic heart failure patients. J. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkein, J.; Tabruyn, S.P.; Ricke-Hoch, M.; Haghikia, A.; Nguyen, N.Q.; Scherr, M.; Castermans, K.; Malvaux, L.; Lambert, V.; Thiry, M.; et al. MicroRNA-146a is a therapeutic target and biomarker for peripartum cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 2143–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.G.; Watanabe, S.; Lee, A.; Gorski, P.A.; Lee, P.; Jeong, D.; Liang, L.; Liang, Y.; Baccarini, A.; Sahoo, S.; et al. miR-146a Suppresses SUMO1 Expression and Induces Cardiac Dysfunction in Maladaptive Hypertrophy. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, O.R.; Goodspeed, A.; Sucharov, C.C.; Powell, T.L.; Jansson, T. Human fetal circulating factors from pregnancies complicated by obesity upregulate genes associated with pathological hypertrophy in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2026, 330, H124–H136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, V.K.; Loughran, K.A.; Meola, D.M.; Juhr, C.M.; Thane, K.E.; Davis, A.M.; Hoffman, A.M. Circulating exosome microRNA associated with heart failure secondary to myxomatous mitral valve disease in a naturally occurring canine model. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2017, 6, 1350088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanganalmath, S.K.; Dubey, S.; Veeranki, S.; Narisetty, K.; Krishnamurthy, P. The interplay of inflammation, exosomes and Ca(2+) dynamics in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Huang, W.; Liu, G.; Cai, W.; Millard, R.W.; Wang, Y.; Chang, J.; Peng, T.; Fan, G.C. Cardiomyocytes mediate anti-angiogenesis in type 2 diabetic rats through the exosomal transfer of miR-320 into endothelial cells. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2014, 74, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.P.; Chang, C.C.; Kuo, C.Y.; Huang, K.J.; Sokal, E.M.; Chen, K.H.; Hung, L.M. Exosomal microRNAs miR-30d-5p and miR-126a-5p Are Associated with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in STZ-Induced Type 1 Diabetic Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Huang, X.; Xu, M.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, F.; Hua, F.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Y. Value of circulating miRNA-21 in the diagnosis of subclinical diabetic cardiomyopathy. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2020, 518, 110944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, V.; Nizamudeen, Z.A.; Lea, D.; Dottorini, T.; Holmes, T.L.; Johnson, B.B.; Arkill, K.P.; Denning, C.; Smith, J.G.W. Transcriptomic Analysis of Cardiomyocyte Extracellular Vesicles in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Reveals Differential snoRNA Cargo. Stem Cells Dev. 2021, 30, 1215–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, X.; Wang, C. Revealing the contribution of iron overload-brown adipocytes to iron overload cardiomyopathy: Insights from RNA-seq and exosomes coculture technology. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 122, 109458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Li, X.; Ge, C.; Pei, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhong, M.; Zhu, X.; Lv, K. M2 macrophage exosome-derived lncRNA AK083884 protects mice from CVB3-induced viral myocarditis through regulating PKM2/HIF-1α axis mediated metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Redox Biol. 2024, 69, 103016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.Y.; Chien, C.S.; Yarmishyn, A.A.; Chou, S.J.; Yang, Y.P.; Wang, M.L.; Wang, C.Y.; Leu, H.B.; Yu, W.C.; Chang, Y.L.; et al. Generation of GLA-Knockout Human Embryonic Stem Cell Lines to Model Autophagic Dysfunction and Exosome Secretion in Fabry Disease-Associated Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Cells 2019, 8, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natrus, L.; Labudzynskyi, D.; Muzychenko, P.; Chernovol, P.; Klys, Y. Plasma-derived exosomes implement miR-126-associated regulation of cytokines secretion in PBMCs of CHF patients in vitro. Acta Biomed. 2022, 93, e2022066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swynghedauw, B. Molecular mechanisms of myocardial remodeling. Physiol. Rev. 1999, 79, 215–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenji, K.; Drazner, M.H.; Rothermel, B.A.; Hill, J.A. Does load-induced ventricular hypertrophy progress to systolic heart failure? Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 289, H8–H16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opie, L.H.; Commerford, P.J.; Gersh, B.J.; Pfeffer, M.A. Controversies in ventricular remodelling. Lancet 2006, 367, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablocki, D.; Sadoshima, J. Solving the cardiac hypertrophy riddle: The angiotensin II-mechanical stress connection. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 1192–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Schans, V.A.; van den Borne, S.W.; Strzelecka, A.E.; Janssen, B.J.; van der Velden, J.L.; Langen, R.C.; Wynshaw-Boris, A.; Smits, J.F.; Blankesteijn, W.M. Interruption of Wnt signaling attenuates the onset of pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension 2007, 49, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bupha-Intr, T.; Haizlip, K.M.; Janssen, P.M. Role of endothelin in the induction of cardiac hypertrophy in vitro. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gava, A.L.; Balarini, C.M.; Peotta, V.A.; Abreu, G.R.; Cabral, A.M.; Vasquez, E.C.; Meyrelles, S.S. Baroreflex control of renal sympathetic nerve activity in mice with cardiac hypertrophy. Auton. Neurosci. 2012, 170, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Komuro, I.; Yazaki, Y. Signalling pathways for cardiac hypertrophy. Cell Signal 1998, 10, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Li, Y.; Hong, J.; Li, C.; Xu, B.; Guo, X.; Mao, J. Serum exosomes derived from spontaneously hypertensive rats induce cardiac hypertrophy in vitro and in vivo by increasing autocrine release of angiotensin II in cardiomyocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 210, 115462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Schulze, P.C. Cardiac Metabolism in Heart Failure and Implications for Uremic Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1034–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, M.; Mauro, D.; Zicarelli, M.; Carullo, N.; Greco, M.; Andreucci, M.; Coppolino, G.; Bolignano, D. miRNAs in Uremic Cardiomyopathy: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Huang, X.; Xie, D.; Shen, M.; Lin, H.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, S.; Zheng, C.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. RNA interactions in right ventricular dysfunction induced type II cardiorenal syndrome. Aging 2021, 13, 4215–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, K.; Hao, J.; Wang, N.; Shen, N.; Jiang, B.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; He, H.; Wang, Z.; et al. Exosomal miR-27a-5p inhibits indoxyl sulfate-induced cardiac dysfunction by targeting the USF2/FUT8 axis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 241, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Gao, W.; Yao, K.; Ge, J. Roles of Exosomes Derived From Immune Cells in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Qin, L.; Peng, Y.; Bai, W.; Wang, Z. Exosomes Derived From Hypertrophic Cardiomyocytes Induce Inflammation in Macrophages via miR-155 Mediated MAPK Pathway. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 606045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobuss, L.; Foinquinos, A.; Jung, M.; Kenneweg, F.; Xiao, K.; Wang, Y.; Zimmer, K.; Remke, J.; Just, A.; Nowak, J.; et al. Pleiotropic cardiac functions controlled by ischemia-induced lncRNA H19. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2020, 146, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, C.; Gao, L.; Zimmerman, M.C.; Zucker, I.H. Myocardial infarction-induced microRNA-enriched exosomes contribute to cardiac Nrf2 dysregulation in chronic heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 314, H928–H939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Hu, G.; Gao, L.; Hackfort, B.T.; Zucker, I.H. Extracellular vesicular MicroRNA-27a* contributes to cardiac hypertrophy in chronic heart failure. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2020, 143, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, H.; Wu, W.; Qi, L.; Tan, W.; Nagarkatti, P.; Nagarkatti, M.; Wang, X.; Cui, T. Autophagy Inhibition Enables Nrf2 to Exaggerate the Progression of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy in Mice. Diabetes 2020, 69, 2720–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; DeMarco, V.G.; Sowers, J.R. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, K.; Haslbeck, M.; Buchner, J. The heat shock response: Life on the verge of death. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, S.; Barutta, F.; Mastrocola, R.; Imperatore, L.; Bruno, G.; Gruden, G. Heat Shock Proteins in Vascular Diabetic Complications: Review and Future Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gu, H.; Huang, W.; Peng, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Qin, D.; Essandoh, K.; Wang, Y.; Peng, T.; et al. Hsp20-Mediated Activation of Exosome Biogenesis in Cardiomyocytes Improves Cardiac Function and Angiogenesis in Diabetic Mice. Diabetes 2016, 65, 3111–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, R.; Bansal, T.; Rana, S.; Datta, K.; Datta Chaudhuri, R.; Chawla-Sarkar, M.; Sarkar, S. Myocyte-Derived Hsp90 Modulates Collagen Upregulation via Biphasic Activation of STAT-3 in Fibroblasts during Cardiac Hypertrophy. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 37, e00611-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Knowlton, A.A. HSP60 trafficking in adult cardiac myocytes: Role of the exosomal pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 292, H3052–H3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Kim, S.C.; Wang, Y.; Gupta, S.; Davis, B.; Simon, S.I.; Torre-Amione, G.; Knowlton, A.A. HSP60 in heart failure: Abnormal distribution and role in cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 293, H2238–H2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C.; Stice, J.P.; Chen, L.; Jung, J.S.; Gupta, S.; Wang, Y.; Baumgarten, G.; Trial, J.; Knowlton, A.A. Extracellular heat shock protein 60, cardiac myocytes, and apoptosis. Circ. Res. 2009, 105, 1186–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, H.S.; Toledo, C.; Andrade, D.C.; Marcus, N.J.; Del Rio, R. Neuroinflammation in heart failure: New insights for an old disease. J. Physiol. 2020, 598, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, D.M.; Lefkovits, J.; Jennings, G.L.; Bergin, P.; Broughton, A.; Esler, M.D. Adverse consequences of high sympathetic nervous activity in the failing human heart. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1995, 26, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartupee, J.; Mann, D.L. Neurohormonal activation in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymperopoulos, A.; Rengo, G.; Koch, W.J. Adrenergic nervous system in heart failure: Pathophysiology and therapy. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 739–753, Erratum in Circ. Res. 2016, 119, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapacciuolo, A.; Esposito, G.; Caron, K.; Mao, L.; Thomas, S.A.; Rockman, H.A. Important role of endogenous norepinephrine and epinephrine in the development of in vivo pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 38, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, R.; Schmidt, A.G.; Pathak, A.; Gerst, M.J.; Biniakiewicz, D.; Kadambi, V.J.; Hoit, B.D.; Abraham, W.T.; Kranias, E.G. Differential regulation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates gender-dependent catecholamine-induced hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003, 57, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Hong, J.; Shanks, J.; Rudebush, T.; Yu, L.; Hackfort, B.T.; Wang, H.; Zucker, I.H.; Gao, L. Upregulating Nrf2 in the RVLM ameliorates sympatho-excitation in mice with chronic heart failure. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 141, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.L.; Chan, S.H.; Chan, J.Y. Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in rostral ventrolateral medulla contribute to neurogenic hypertension induced by systemic inflammation. J. Neuroinflammation 2012, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint-Pol, J.; Gosselet, F.; Duban-Deweer, S.; Pottiez, G.; Karamanos, Y. Targeting and Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier with Extracellular Vesicles. Cells 2020, 9, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.C.; Wang, W.; Gao, Y.; Li, W.Y.; Tan, X.; Wang, Y.K.; Wang, W.Z. The Peripheral Circulating Exosomal microRNAs Related to Central Inflammation in Chronic Heart Failure. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2022, 15, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.H.; Chen, D.Q.; Wang, Y.N.; Feng, Y.L.; Cao, G.; Vaziri, N.D.; Zhao, Y.Y. New insights into TGF-β/Smad signaling in tissue fibrosis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 292, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Gao, F.; Jiang, J.; Lu, Y.W.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; Fu, X.; Dong, X.; Pei, J.; et al. Loss of Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog Promotes Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Cardiac Repair After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2020, 142, 2196–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, J.; Ramanujam, D.; Sassi, Y.; Ahles, A.; Jentzsch, C.; Werfel, S.; Leierseder, S.; Loyer, X.; Giacca, M.; Zentilin, L.; et al. MiR-378 controls cardiac hypertrophy by combined repression of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway factors. Circulation 2013, 127, 2097–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, H.B.; Gao, W.; Zhang, L.; Ye, Y.; Yuan, L.Y.; Ding, Z.W.; Wu, J.; Kang, L.; Zhang, X.Y.; et al. MicroRNA-378 suppresses myocardial fibrosis through a paracrine mechanism at the early stage of cardiac hypertrophy following mechanical stress. Theranostics 2018, 8, 2565–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, C.; Batkai, S.; Dangwal, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Foinquinos, A.; Holzmann, A.; Just, A.; Remke, J.; Zimmer, K.; Zeug, A.; et al. Cardiac fibroblast-derived microRNA passenger strand-enriched exosomes mediate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 2136–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Qin, Q.; Qi, L.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P.; Janicki, J.S.; Wang, X.L.; Cui, T. A critical role of cardiac fibroblast-derived exosomes in activating renin angiotensin system in cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2015, 89, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Fan, J.; Li, H.; Yin, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, B.; Dong, N.; Chen, C.; Wang, D.W. miR-217 Promotes Cardiac Hypertrophy and Dysfunction by Targeting PTEN. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 12, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Ha, T.; Que, L.; Liu, L.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Q.; et al. Pellino1-mediated TGF-β1 synthesis contributes to mechanical stress induced cardiac fibroblast activation. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2015, 79, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Hou, Y.X.; Shi, P.X.; Zhu, C.H.; Lu, X.; Wang, X.L.; Que, L.L.; Zhu, G.Q.; Liu, L.; Chen, Q.; et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific Peli1 contributes to the pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis through miR-494-3p-dependent exosomal communication. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e22699, Erratum in FASEB J. 2023, 37, e22860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Stroud, M.J.; Ouyang, K.; Fang, L.; Zhang, J.; Dalton, N.D.; Gu, Y.; Wu, T.; Peterson, K.L.; Huang, H.D.; et al. Adipocyte-specific loss of PPARgamma attenuates cardiac hypertrophy. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e89908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.C. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-Derived Exosomes for Precision Medicine in Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, W.D.; French, K.M.; Ghosh-Choudhary, S.; Maxwell, J.T.; Brown, M.E.; Platt, M.O.; Searles, C.D.; Davis, M.E. Identification of therapeutic covariant microRNA clusters in hypoxia-treated cardiac progenitor cell exosomes using systems biology. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Hu, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Ma, H.; Huang, K.; Li, Z.; Su, T.; Vandergriff, A.; Tang, J.; et al. microRNA-21-5p dysregulation in exosomes derived from heart failure patients impairs regenerative potential. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 2237–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamiak, M.; Cheng, G.; Bobis-Wozowicz, S.; Zhao, L.; Kedracka-Krok, S.; Samanta, A.; Karnas, E.; Xuan, Y.T.; Skupien-Rabian, B.; Chen, X.; et al. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Are Safer and More Effective for Cardiac Repair Than iPSCs. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Räsänen, M.; Degerman, J.; Nissinen, T.A.; Miinalainen, I.; Kerkelä, R.; Siltanen, A.; Backman, J.T.; Mervaala, E.; Hulmi, J.J.; Kivelä, R.; et al. VEGF-B gene therapy inhibits doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by endothelial protection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 13144–13149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Yang, Y.; Bai, B.; Wang, S.; Liu, M.; Sun, R.C.; Yu, T.; Chu, X.M. Potential of exosomes as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic carriers for doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 1328–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Liu, Y.; Kang, L.; Wang, L.; Han, Z.; Wang, K.; Xu, B.; Gu, R. Human trophoblast-derived exosomes attenuate doxorubicin-induced cardiac injury by regulating miR-200b and downstream Zeb1. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 18, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; Liu, X.; Shen, S.; Tan, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Kang, L.; Wang, K.; Wei, Z.; Qi, Y.; et al. Trophoblast Stem-Cell-Derived Exosomes Alleviate Cardiotoxicity of Doxorubicin via Improving Mfn2-Mediated Mitochondrial Fusion. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2023, 23, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Ma, M.; Wang, D.; Xia, J.; Wang, X.; Hou, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Attenuate Transverse Aortic Constriction Induced Heart Failure by Increasing Angiogenesis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 638771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Liu, B.; Su, X.; Tian, X.; Wang, H. Unlocking cardioprotection: iPSC exosomes deliver Nec-1 to target PARP1/AIFM1 axis, alleviating HF oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijter, J.P.; van Rooij, E. Exosomal microRNA clusters are important for the therapeutic effect of cardiac progenitor cells. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Shen, C.; Qin, G.; Ashraf, M.; Weintraub, N.; Ma, G.; Tang, Y. Cardiac progenitor-derived exosomes protect ischemic myocardium from acute ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 431, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Pan, Y.; Li, X.H.; Yang, X.Y.; Feng, Y.L.; Tan, H.H.; Jiang, L.; Feng, J.; Yu, X.Y. Cardiac progenitor cell-derived exosomes prevent cardiomyocytes apoptosis through exosomal miR-21 by targeting PDCD4. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Gaussin, V.; Taffet, G.E.; Belaguli, N.S.; Yamada, M.; Schwartz, R.J.; Michael, L.H.; Overbeek, P.A.; Schneider, M.D. TAK1 is activated in the myocardium after pressure overload and is sufficient to provoke heart failure in transgenic mice. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Li, Y.D.; Chen, R.L.; Li, G.; Zhou, X.X.; Song, F.; Wu, C.; Hu, Y.; Hong, Y.X.; Dang, X.; et al. Heart-targeting exosomes from human cardiosphere-derived cells improve the therapeutic effect on cardiac hypertrophy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Y.; Wang, C.; Benedict, C.; Huang, G.; Truongcao, M.; Roy, R.; Cimini, M.; Garikipati, V.N.S.; Cheng, Z.; Koch, W.J.; et al. Interleukin-10 Deficiency Alters Endothelial Progenitor Cell-Derived Exosome Reparative Effect on Myocardial Repair via Integrin-Linked Kinase Enrichment. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, L.; Feng, Z.; Chen, W.; Yan, S.; Yang, R.; Xiao, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, D.; Ke, X. EPC-Derived Exosomal miR-1246 and miR-1290 Regulate Phenotypic Changes of Fibroblasts to Endothelial Cells to Exert Protective Effects on Myocardial Infarction by Targeting ELF5 and SP1. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 647763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, E.; Fujita, D.; Takahashi, M.; Oba, S.; Nishimatsu, H. Therapeutic Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes in Cardiovascular Disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 998, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Qiu, F.; Cao, H.; Li, H.; Dai, G.; Ma, T.; Gong, Y.; Luo, W.; Zhu, D.; Qiu, Z.; et al. Therapeutic delivery of microRNA-125a-5p oligonucleotides improves recovery from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice and swine. Theranostics 2023, 13, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, G.; Yan, B. The Application Potential and Advance of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes in Myocardial Infarction. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 5579904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kita, S.; Maeda, N.; Shimomura, I. Interorgan communication by exosomes, adipose tissue, and adiponectin in metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 4041–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Kita, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Obata, Y.; Okita, T.; Nishida, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Kawachi, Y.; Tsugawa-Shimizu, Y.; et al. Adiponectin Stimulates Exosome Release to Enhance Mesenchymal Stem-Cell-Driven Therapy of Heart Failure in Mice. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 2203–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Basavana Gowda, M.K.; Lee, M.; Masagalli, J.N.; Mailar, K.; Choi, W.J.; Noh, M. Novel linked butanolide dimer compounds increase adiponectin production during adipogenesis in human mesenchymal stem cells through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ modulation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 187, 111969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabeebaccus, A.; Zheng, S.; Shah, A.M. Heart failure-potential new targets for therapy. Br. Med. Bull. 2016, 119, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, D.; Wang, S.; Lin, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, W. Exosomal microRNA-1246 from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells potentiates myocardial angiogenesis in chronic heart failure. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 45, 2211–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenča, D.; Melenovský, V.; Stehlik, J.; Staněk, V.; Kettner, J.; Kautzner, J.; Adámková, V.; Wohlfahrt, P. Heart failure after myocardial infarction: Incidence and predictors. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausenloy, D.J.; Yellon, D.M. Ischaemic conditioning and reperfusion injury. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Hu, X.; Wu, C.; Chan, J.; Liu, Z.; Guo, C.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, S.; et al. Plasma exosomes generated by ischaemic preconditioning are cardioprotective in a rat heart failure model. Br. J. Anaesth. 2023, 130, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Zhao, L.; Lu, F.; Gao, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, M.; Yang, G.; Xing, C.; Liu, L. Mononuclear phagocyte system blockade improves therapeutic exosome delivery to the myocardium. Theranostics 2020, 10, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, J.; Gong, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yi, S.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Xie, X.; Yi, C.; et al. Recent Progress in Microneedles-Mediated Diagnosis, Therapy, and Theranostic Systems. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, e2102547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Yang, H.; Liu, C.; Shao, L.; Zhang, H.; Lu, K.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Microneedle Patch Loaded with Exosomes Containing MicroRNA-29b Prevents Cardiac Fibrosis after Myocardial Infarction. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, e2202959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhmerov, A.; Parimon, T. Extracellular Vesicles, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glezeva, N.; Voon, V.; Watson, C.; Horgan, S.; McDonald, K.; Ledwidge, M.; Baugh, J. Exaggerated inflammation and monocytosis associate with diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Evidence of M2 macrophage activation in disease pathogenesis. J. Card. Fail. 2015, 21, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, I.K.; Wood, M.J.A.; Fuhrmann, G. Extracellular vesicles as a next-generation drug delivery platform. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lener, T.; Gimona, M.; Aigner, L.; Börger, V.; Buzas, E.; Camussi, G.; Chaput, N.; Chatterjee, D.; Court, F.A.; Del Portillo, H.A.; et al. Applying extracellular vesicles based therapeutics in clinical trials—An ISEV position paper. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 30087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Hu, X.; Wang, J. Current optimized strategies for stem cell-derived extracellular vesicle/exosomes in cardiac repair. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2023, 184, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, D.; Pan, X.; Liang, Y. Targeted therapy using engineered extracellular vesicles: Principles and strategies for membrane modification. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, F.; Xu, J.; Yin, W.; Zhang, S.; Wei, G.; Yin, J.; Yi, H.; et al. Myocardial delivery of miR30d with peptide-functionalized milk-derived extracellular vesicles for targeted treatment of hypertrophic heart failure. Biomaterials 2025, 316, 122976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zeng, Y.; Tan, X.; Zhang, G.; Xu, A.; Fan, H.; Yu, F.; Qin, Z.; Song, Y.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Targeted Delivery of Exosome-Derived miRNA-185-5p Inhibitor via Liposomes Alleviates Apoptosis and Cuproptosis in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 9407–9425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Marsh, J.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Nie, L. Engineered extracellular vesicles as intelligent nanosystems for next-generation nanomedicine. Nanoscale Horiz. 2022, 7, 682–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Hong, W.; Mo, Y.; Shu, F.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Tan, N.; Jiang, L. Stem cells derived exosome laden oxygen generating hydrogel composites with good electrical conductivity for the tissue-repairing process of post-myocardial infarction. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witwer, K.W.; Goberdhan, D.C.; O’Driscoll, L.; Théry, C.; Welsh, J.A.; Blenkiron, C.; Buzás, E.I.; Di Vizio, D.; Erdbrügger, U.; Falcón-Pérez, J.M.; et al. Updating MISEV: Evolving the minimal requirements for studies of extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu, R.C.; Fernandes, H.; da Costa Martins, P.A.; Sahoo, S.; Emanueli, C.; Ferreira, L. Native and bioengineered extracellular vesicles for cardiovascular therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, H.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Liao, Z.; Wei, S.; Ruan, H.; Li, T.; Chen, J. A novel circ_0018553 protects against angiotensin-induced cardiac hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes by modulating the miR-4731/SIRT2 signaling pathway. Hypertens. Res. 2023, 46, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Na, N.; Ijichi, T.; Wu, X.; Miyamoto, K.; Ciullo, A.; Tran, M.; Li, L.; Ibrahim, A.; Marban, E.; et al. Exosomally derived Y RNA fragment alleviates hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 24, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Etiology/HF Context | Study Population/Design | EV Source | EV Cargo/Marker(s) | Key Findings/Clinical Relevance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic HF (mixed ischemic/non-ischemic) | HF patients vs. healthy controls, cross-sectional | Plasma exosomes | miR-146a, miR-486, miR-16 (ratios miR-146a/miR-16, miR-486/miR-16) | Increased exosomal miRNA ratios in HF vs. controls added diagnostic value | [58] |

| Acute HFrEF | Hospitalized acute HFrEF patients vs. healthy volunteers | Serum exosomes | miR-92b-5p, miR-192-5p, miR-320a | Selective elevation of exosomal miR-92b-5p in acute HFrEF | [59] |

| Acute HF and cardiac fibrosis | Patients with acute HF vs. controls | Plasma exosomes | miR-21, miR-425, miR-744 | Imbalanced exosomal miR-21/miR-425/miR-744 associated with fibrosis and HF progression | [62] |

| Post-AMI risk of ischemic HF | Post-AMI patients with vs. without HF during follow-up | Serum exosomes | miR-192, miR-194, miR-34a (p53-responsive miRNAs) | p53-related exosomal miRNAs predicting post-AMI ischemic HF | [63] |

| Chronic HF severity/prognosis | HF cohort with longitudinal outcome follow-up | Plasma endothelial EVs and apoptotic microparticles | CD31+/CD144+ EVs, CD144+/CD31+/Annexin V+ microparticles | Endothelial EVs/microparticles associated with HF severity and adverse prognosis | [64,65,66] |

| PPCM-HF | PPCM patients vs. DCM patients; serial sampling | Peripheral blood exosomes | miR-146a | Exosomal miR-146a as PPCM-specific diagnostic and prognostic marker | [67] |

| Maternal obesity—offspring cardiac programming | Umbilical cord samples from obese mothers; in vitro cardiomyocyte assays | Umbilical cord serum EVs | miR-142, miR-17 (and other cargo) | Cord EVs from obese mothers inducing pro-hypertrophic responses in neonatal cardiomyocytes | [69] |

| MMVD and chronic HF (veterinary) | Dogs with MMVD, MMVD-CHF and aging controls | Plasma exosomes vs. total plasma | miR-9, miR-495, miR-599, miR-181c and others | Exosomal miR-181c/miR-495 as MMVD-CHF–related biomarkers (veterinary) | [70] |

| Diabetic cardiomyopathy in T2DM | T2DM patients with vs. without DCM | Plasma (circulating miRNAs) | miR-21 | Reduced plasma miR-21 indicating DCM in T2DM | [74] |

| HCM (patient-derived cellular model) | ACTC1-mutant HCM hiPSC-CMs vs. control hiPSC-CMs | hiPSC-cardiomyocyte-derived EVs | A total of 12 snoRNAs (10 SNORDs, 2 SNORAs) and enriched transcripts | Distinct snoRNA/transcript signature in HCM cardiomyocyte EVs as biomarker candidates | [75] |

| Chronic HF—EV-based immunomodulation | PBMCs from chronic HF patients treated in vitro | EVs from healthy donor plasma | Global EV cargo; miR-126 changes in PBMCs | Healthy donor EVs modulating CHF PBMC inflammation; immunomodulatory therapy proof-of-concept | [79] |

| EVs Origin | Cargoes | Target Gene/Pathways | Outcomes/Functions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR serum | — | Carry angiotensinogen, renin, and ACE into cardiomyocytes to increase autocrine secretion of Ang II | Cardiac hypertrophy ↑ | [88] |

| Indoxyl sulfate-induced cardiac microvascular endothelial cell (CMEC) | miR-27a-5p | Target USF2/FUT8 axis in cardiomyocytes | Reactive oxygen species (ROS) ↑ Cardiac apoptosis ↑ Cardiac hypertrophy ↑ | [92] |

| Ang II-induced hypertrophic cardiomyocytes | miR-155 | Induce phosphorylation of ERK, JNK and p38 | Macrophages inflammatory response ↑ | [94] |

| MI mouses cardiomyocytes | lncRNA H19 | NF-κB signaling pathway | Cardiac apoptosis inflammation ↓ Cardiac abnormal remodeling ↓ Exaggerated hypertrophy of ischemia-reperfused myocardium due to H19 knockout | [95] |

| TNF-α-stressed cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts | miR-27a, miR-29-3p, and miR-34a | Inhibit the translation of Nrf2 and the expression of antioxidant genes | Ischemic heart failure ↑ | [96,97] |

| CFs/CHF rat | miR-27a guest strand | Inhibit PDLIM5 translation in cardiomyocytes; Induce AngII expression | Cardiac hypertrophy ↑ Myocardial contractility ↓ | [97] |

| Cardiomyocytes/Mice | HSP20 | Interact with TSG101 | Exosomes biogenesis and release ↑ Cardiac hypertrophy ↓ Myocardial apoptosis ↓ Myocardial fibrosis ↓ | [102] |

| Cardiomyocytes | HSP90 | Activate STAT-3 signaling pathway | Cardiac hypertrophy ↑ Cardiac function ↓ | [103] |

| Serum/CHF rats | miR-214-3p | Enhance the inflammatory response of RVLM, hyperactive nervous system | Heart failure ↑ | [116] |

| CFs/TAC mice | miR-21-3p | Target SORBS2 and PDLIM5 | Cardiac hypertrophy ↑ | [121] |

| Angiotensin II treated mice CFs | —— | AngII enhances exosomes release via targeting AT1R and AT2R; exosomes upregulate RAS via activation of MAPK and Akt | Cardiac hypertrophy ↑ | [122] |

| CHF patients/TAC mice | miR-217 | Target PTEN | Heart size ↑ Cardiac hypertrophy ↑ Myocardial fibrosis ↑ | [123] |

| Peli1-induced cardiomyocyte | miR-494-3p | Inhibit PTEN and promote Akt, SMAD2/3, and ERK signaling pathway | Cardiac necrosis ↑ Heart failure ↑ | [125] |

| Adipocytes | miR-200a | Decrease TSC1 and subsequent mTOR activation in cardiomyocytes | Cardiac hypertrophy ↑ | [126] |

| EVs Origin | Cargoes | Target Gene/Pathways | Outcomes/Functions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiomyocytes in mammals | miR-378 | Target MKK6, attenuate p38 MAPK phosphorylation; downregulate p38 MAPK-Smad2/3 pathway | Cardiac hypertrophy ↓ Myocardial fibrosis ↓ | [120] |

| Transplant-derived cardiac stromal cells from HF patients | miR-21-5p | Inhibit PTEN, enhance Akt kinase activity | Cardiomyocyte survival ↑ Heart failure ↓ | [129] |

| Stem cell-derived exosomes (TSC-Exos) | N/A | Anti-inflammation: Block DOX-activated NF-κB inflammatory signaling pathway Anti-apoptosis; downregulate miR-200b expression and increase Zeb1 expression | Inflammation ↓ Myocardial apoptosis ↓ DOX-induced cardiac injury ↓ | [133] |

| TSC-Exos | N/A | Improve mitochondrial fusion and increase Mfn2 expression | DOX-induced cardiac injury ↓ | [134] |

| CPCs | miR-21 | Target PDCD4 Inhibit apoptosis of H9C2 | Cardiac hypertrophy ↓ Myocardial apoptosis ↓ Myocardial fibrosis ↓ Heart failure ↓ | [139] |

| EPC | Circ_0018553 | Target miR-4731/SIRT2 signaling pathway | Cardiac hypertrophy ↓ | [170] |

| CDCs/Human | miR-148a | Inhibit GP130 Suppress STAT3/ERK1/2/AKT pathway | Cardiac hypertrophy ↓ | [141] |

| CDCs | YF1 | Downregulate JNK and Smad2 phosphorylation; attenuate CXCL1 expression in cardiomyocytes | Cardiac hypertrophy ↓ Myocardial fibrosis ↓ Myocardial apoptosis ↓ Myocardial fibrosis ↓ | [171] |

| hucMSCs | miR-1246 | Inhibit Snail/alpha-smooth muscle actin signaling | Angiogenesis ↑ Heart failure ↓ | [151] |

| Normal rats undergoing IPC | pro-survival protein kinase | Phosphorylation of downstream ERK and AKT | Restore cardioprotection in HF after MI | [154] |

| EVs from HucMSCs | miR-29b | Inhibit TGF-β/SMAD3 signaling pathway | Cardiac necrosis ↓ | [157] |

| EVs from healthy donor plasma | N/A | Decrease miRNA-126 expression; reduce the release of inflammatory factors | Cardioprotective effects ↑ | [79] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, J.; Zhou, D.; Cheng, M. Potential Biomarker and Therapeutic Tools for Pathological Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure: Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010095

Sun J, Zhou D, Cheng M. Potential Biomarker and Therapeutic Tools for Pathological Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure: Extracellular Vesicles. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010095

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Jinpeng, Dongli Zhou, and Min Cheng. 2026. "Potential Biomarker and Therapeutic Tools for Pathological Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure: Extracellular Vesicles" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010095

APA StyleSun, J., Zhou, D., & Cheng, M. (2026). Potential Biomarker and Therapeutic Tools for Pathological Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure: Extracellular Vesicles. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010095