Influence of Peptide-Rich Nitrogen Sources on GAD System Activation and GABA Production in Levilactobacillus brevis CRL 2013

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

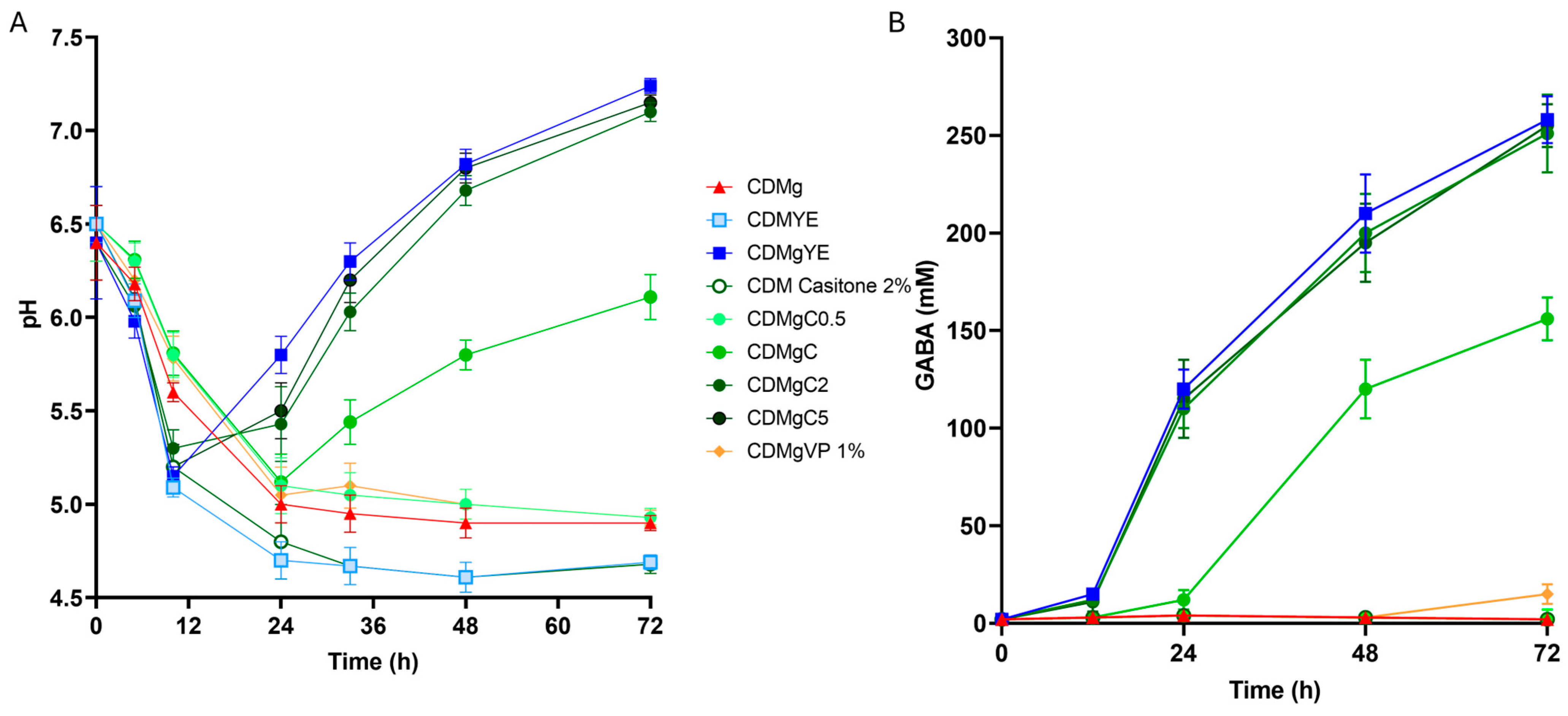

2.1. Effect of Nitrogen Source Supplementation on GABA Production and pH

2.2. Effect of Peptide Size and Defined Peptides on GABA Biosynthesis

2.3. Proteomic Profiling of Lv. brevis CRL 2013 Under Different Nitrogen Supplementation Conditions

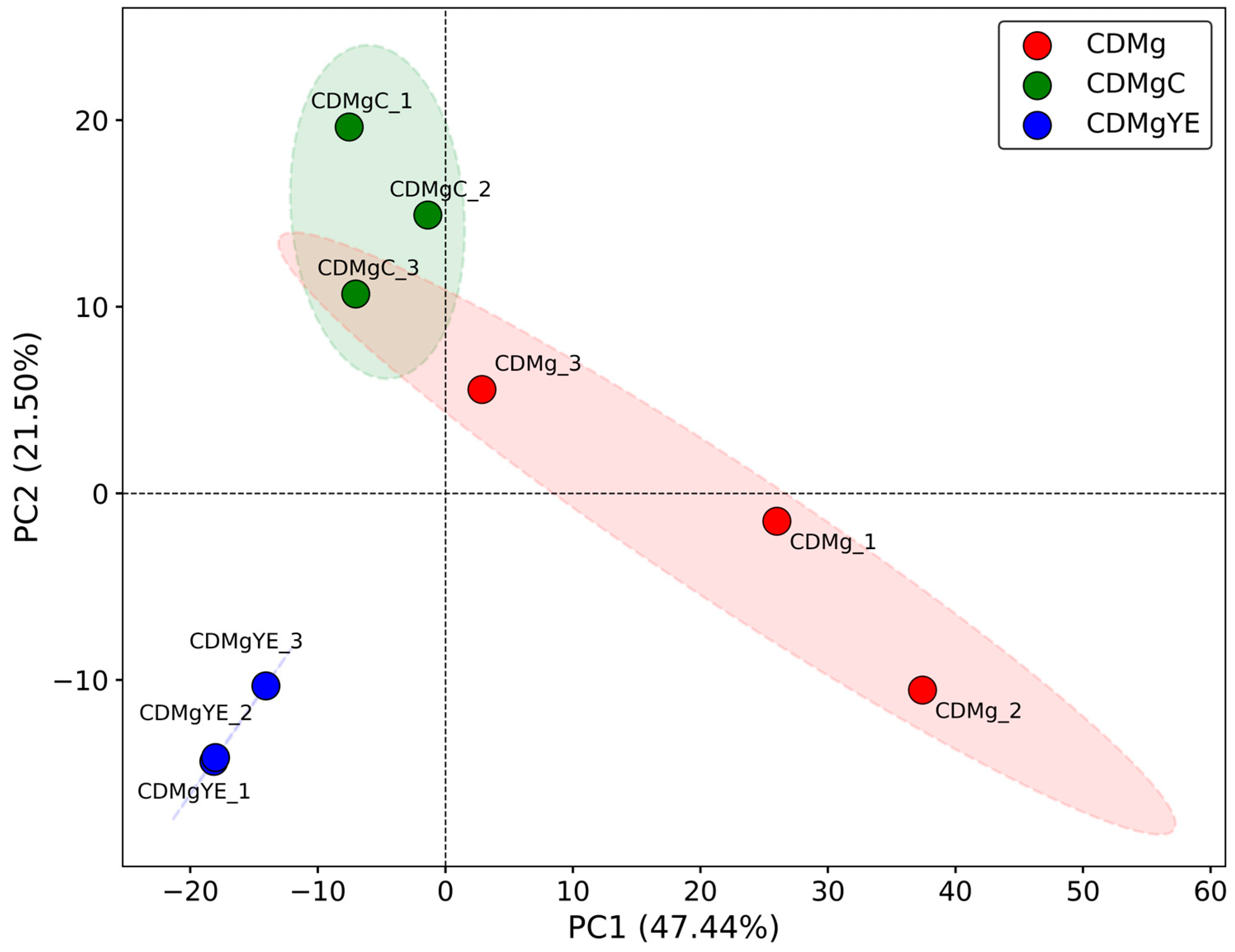

2.3.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

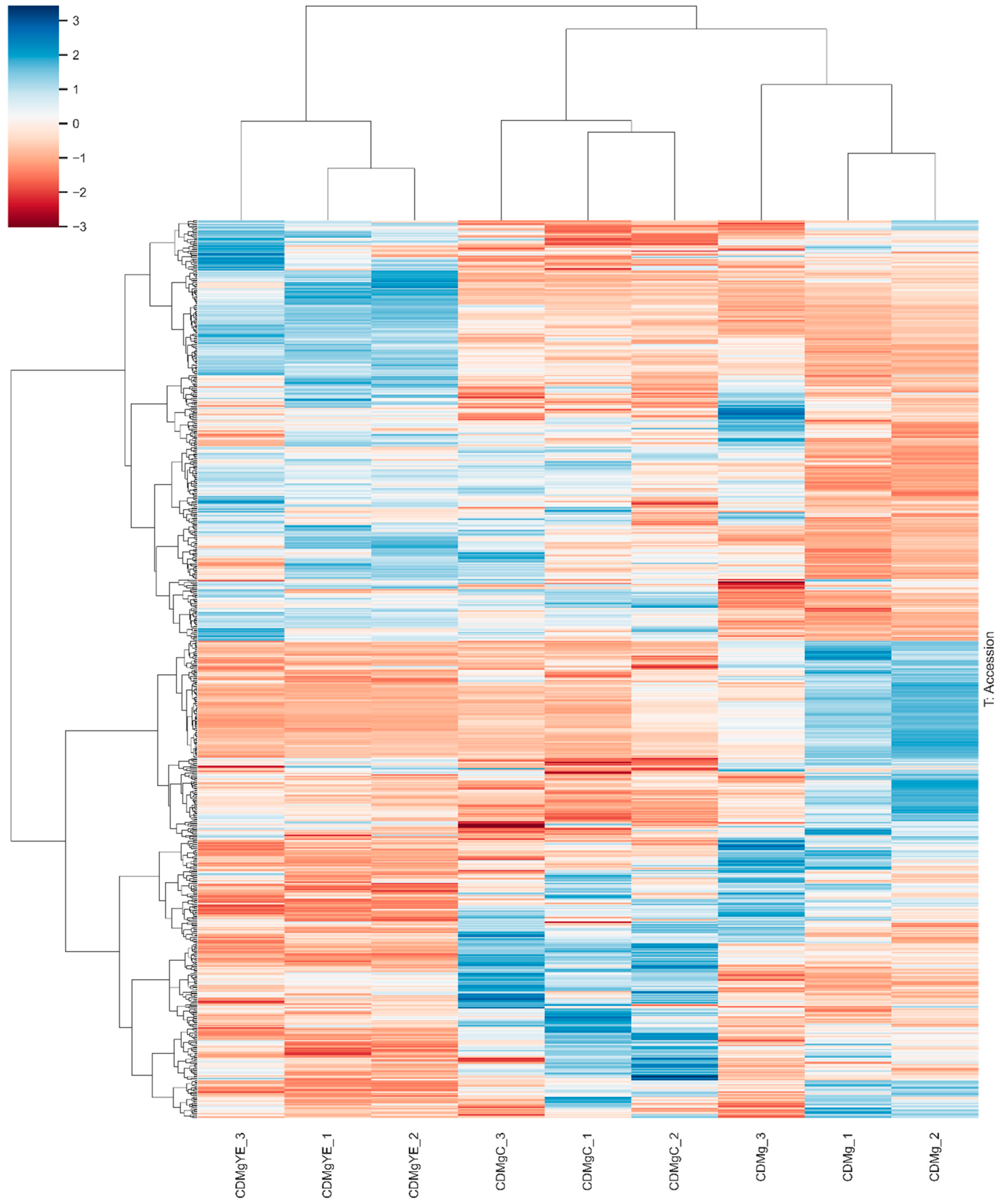

2.3.2. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis

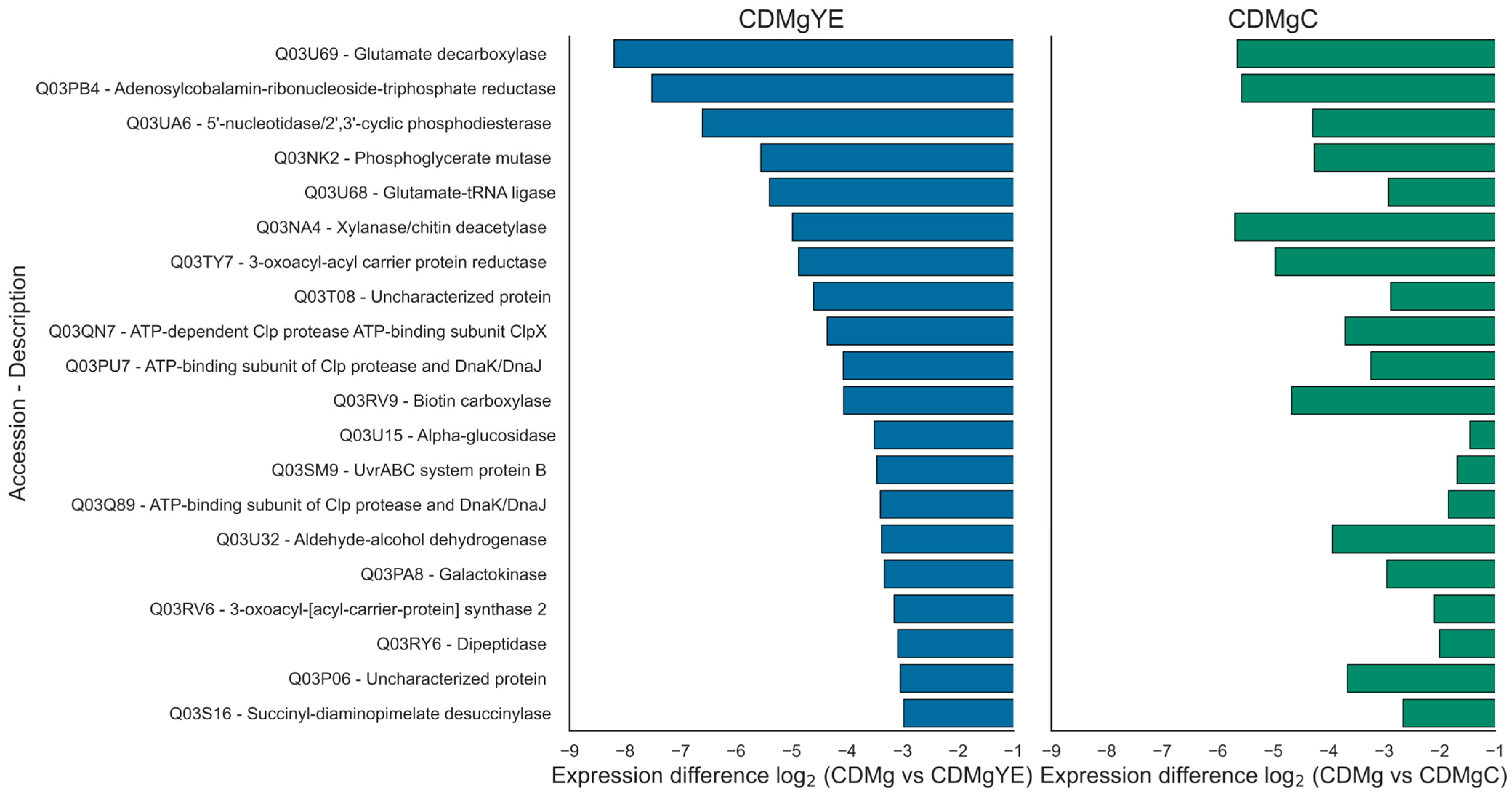

2.3.3. Distribution and Comparative Expression of DEPs

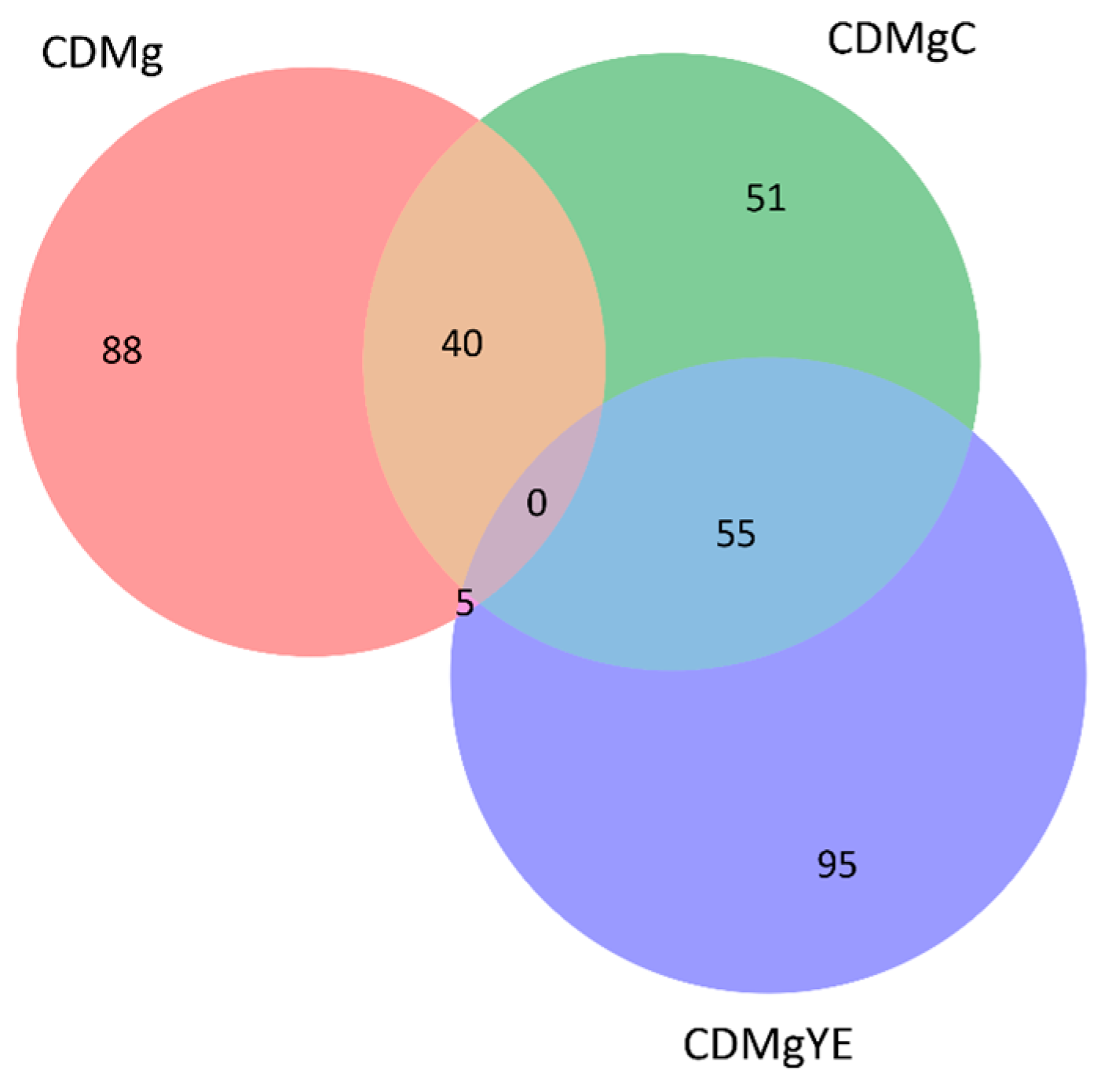

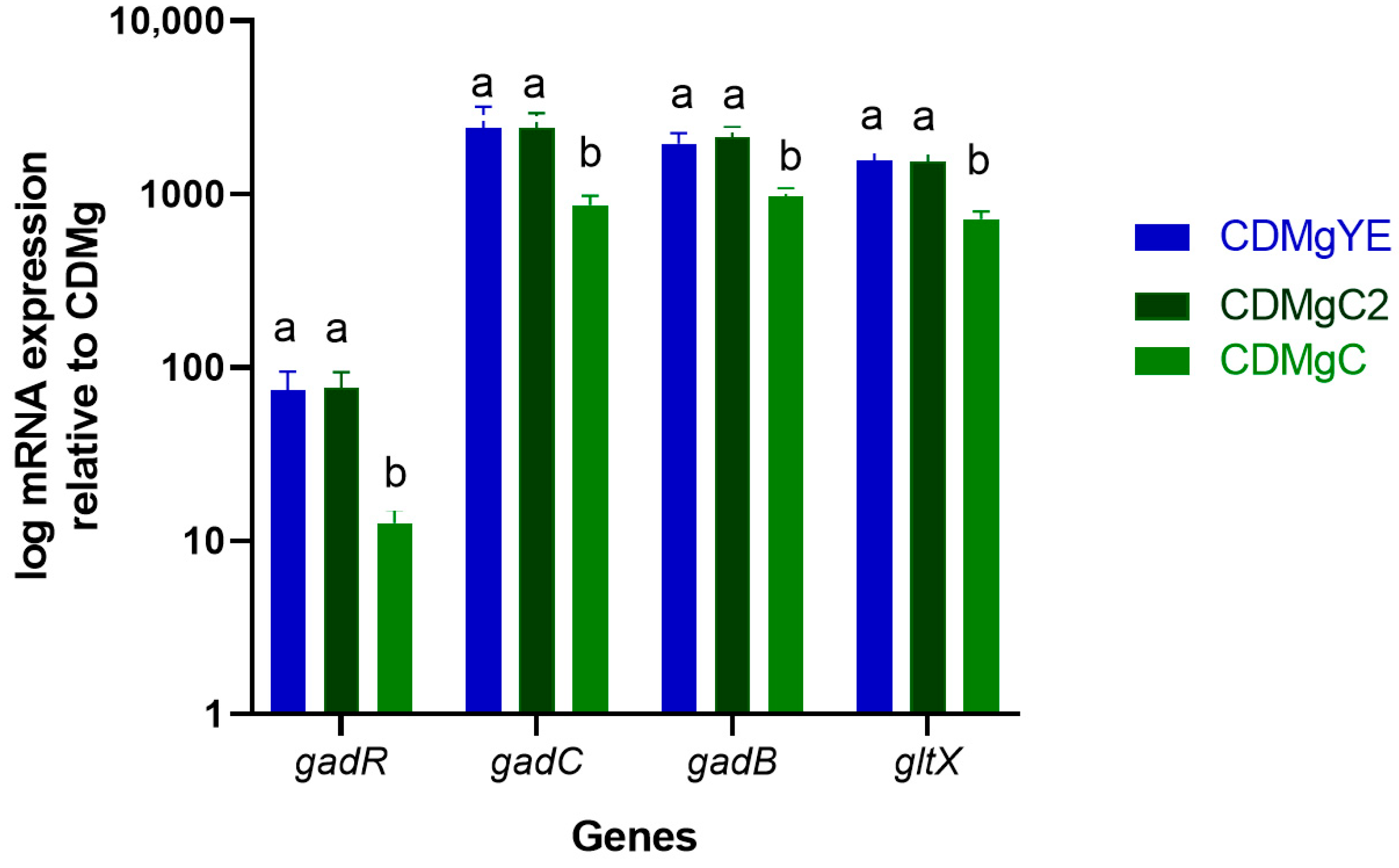

2.4. Transcriptional Analysis of GABA-Related Genes by RT-qPCR

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Microorganisms, Culture Media, and Growth Conditions

4.2. Nitrogen Source Fractionation and Peptide Supplementation Assays

4.3. GABA Measurements

4.4. Proteomic Analysis

4.4.1. Sample Preparation

4.4.2. LC-MS/MS Data Acquisition

4.4.3. Protein Identification and Quantification

4.4.4. Proteomic Data Analysis

4.5. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

4.5.1. Total RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

4.5.2. qPCR Assay

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paventi, G.; Di Martino, C.; Crawford, T.W., Jr.; Iorizzo, M. Enzymatic activities of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: Technological and functional role in food processing and human nutrition. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Miao, K.; Niyaphorn, S.; Qu, X. Production of gamma-aminobutyric acid from lactic acid bacteria: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Gutiérrez, L.; San Vicente, L.; Barrón, L.J.R.; Villarán, M.d.C.; Chávarri, M. Gamma-aminobutyric acid and probiotics: Multiple health benefits and their future in the global functional food and nutraceuticals market. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 64, 103669–103683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoli, R.; Pessione, E. The neuro-endocrinological role of microbial glutamate and GABA signaling. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatzas, K.A.; Suur, L.; O’Byrne, C.P. Characterization of the intracellular glutamate decarboxylase system: Analysis of its function, transcription, and role in the acid resistance of various strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 3571–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumbeck, J.A.; Marsteller, N.L.; Frese, S.A.; Peterson, D.A.; Ramer-Tait, A.E.; Hutkins, R.W.; Walter, J. Characterization of the ecological role of genes mediating acid resistance in Lactobacillus reuteri during colonization of the gastrointestinal tract. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 2172–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, J.A.; Forsythe, P.; Chew, M.V.; Escaravage, E.; Savignac, H.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Bienenstock, J.; Cryan, J.F. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16050–16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auteri, M.; Zizzo, M.G.; Serio, R. GABA and GABA receptors in the gastrointestinal tract: From motility to inflammation. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 93, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaker, M.A.; Ghany, K.A.E.; Elshafey, N.; Algohary, A.M.; Elgohary, E.; Hamouda, R.A.; Abol-Fetouh, G.M.; Elbawab, R.H.; Ahmed-Farid, O.A. GABA-enriched probiotic nanoformulation: A novel nutritional intervention against acrylamide neurotoxicity and inflammation. Food Biosci. 2025, 71, 107194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, R.; Choudhury, P.K. Lactic acid bacteria in fermented dairy foods: Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production and its therapeutic implications. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, J.D.; Thongngam, M.; Kumrungsee, T. Gamma-aminobutyric acid as a potential postbiotic mediator in the gut–brain axis. npj Sci. Food 2024, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulacios, G.A.; Cataldo, P.G.; Naja, J.R.; de Chaves, E.P.; Taranto, M.P.; Minahk, C.J.; Hebert, E.M.; Saavedra, M.L. Improvement of key molecular events linked to Alzheimer’s disease pathology using postbiotics. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 48042–48049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quílez, J.; Diana, M. Chapter 5-Gamma-aminobutyric acid-enriched fermented foods. In Fermented Foods in Health and Disease Prevention; Frias, J., Martinez-Villaluenga, C., Peñas, E., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, P.G.; Villena, J.; Elean, M.; Savoy de Giori, G.; Saavedra, L.; Hebert, E.M. Immunomodulatory properties of a γ-aminobutyric acid-enriched strawberry juice produced by Levilactobacillus brevis CRL 2013. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 3176–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icer, M.A.; Sarikaya, B.; Kocyigit, E.; Atabilen, B.; Çelik, M.N.; Capasso, R.; Ağagündüz, D.; Budán, F. Contributions of gamma-aminobutyric acid (gaba) produced by lactic acid bacteria on food quality and human health: Current Applications and Future Prospects. Foods 2024, 13, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products. Scientific opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to gamma-aminobutyric acid and cognitive function (ID 1768) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.; Villegas, J.M.; Elean, M.; Fadda, S.; Mozzi, F.; Saavedra, L.; Hebert, E.M. YebC, a putative transcriptional factor involved in the regulation of the proteolytic system of Lactobacillus. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8579–8591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, P.G.; Urquiza Martinez, M.P.; Villena, J.; Kitazawa, H.; Saavedra, L.; Hebert, E.M. Comprehensive characterization of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production by Levilactobacillus brevis CRL 2013: Insights from physiology, genomics, and proteomics. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1408624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Zhao, W.; Peng, C.; Hu, S.; Fang, H.; Hua, Y.; Yao, S.; Huang, J.; Mei, L. Exploring the contributions of two glutamate decarboxylase isozymes in Lactobacillus brevis to acid resistance and gamma-aminobutyric acid production. Microb. Cell Fact. 2018, 17, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Poore, M.; Gerdes, S.; Nedveck, D.; Lauridsen, L.; Kristensen, H.T.; Jensen, H.M.; Byrd, P.M.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Patterson, E.; et al. Transcriptomics reveal different metabolic strategies for acid resistance and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production in select Levilactobacillus brevis strains. Microb. Cell Fact. 2021, 20, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, R.; O’Byrne, C.P.; Karatzas, K.A. Amino acids other than glutamate affect the expression of the GAD system in Listeria monocytogenes enhancing acid resistance. Food Microbiol. 2020, 90, 103481–103490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroute, V.; Aubry, N.; Audonnet, M.; Mercier-Bonin, M.; Daveran-Mingot, M.-L.; Cocaign-Bousquet, M. Natural diversity of lactococci in γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production and genetic and phenotypic determinants. Microb. Cell Fact. 2023, 22, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzas, K.A.; Brennan, O.; Heavin, S.; Morrissey, J.; O’Byrne, C.P. Intracellular accumulation of high levels of gamma-aminobutyrate by Listeria monocytogenes 10403S in response to low pH: Uncoupling of gamma-aminobutyrate synthesis from efflux in a chemically defined medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 3529–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marugg, J.D.; Meijer, W.; Van Kranenburg, R.; Laverman, P.; Bruinenberg, P.G.; Vos, W.M.D. Medium-dependent regulation of proteinase gene expression in Lactococcus lactis: Control of transcription initiation by specific dipeptides. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 2982–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Biase, D.; Pennacchietti, E. Glutamate decarboxylase-dependent acid resistance in orally acquired bacteria: Function, distribution and biomedical implications of the gadBC operon. Mol. Microbiol. 2012, 86, 770–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinness, K.E.; Sauer, R.T. Ribosomal protein S1 binds mRNA and tmRNA similarly but plays distinct roles in translation of these molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 13454–13459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Ren, C.; Xu, Y. Deciphering the crucial roles of transcriptional regulator GadR on gamma-aminobutyric acid production and acid resistance in Lactobacillus brevis. Microb. Cell Fact. 2019, 18, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hu, K.; Mou, J.; Li, J.; Liu, A.; Ao, X.; Yang, Y.; He, L.; Chen, S.; Zou, L.; et al. Insight into the acid tolerance mechanism of Acetilactobacillus jinshanensis subsp. aerogenes Z-1. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1226031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, N.W.; Mills, C.E.; Abrahamson, C.H.; Archer, A.G.; Shirman, S.; Jewett, M.C.; Mangan, N.M.; Tullman-Ercek, D. Linking the Salmonella enterica 1,2-propanediol utilization bacterial microcompartment shell to the enzymatic core via the shell protein PduB. J. Bacteriol. 2022, 204, e0057621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlothauer, T.; Mogk, A.; Dougan, D.A.; Bukau, B.; Turgay, K. MecA, an adaptor protein necessary for ClpC chaperone activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2306–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermassen, A.; Leroy, S.; Talon, R.; Provot, C.; Popowska, M.; Desvaux, M. Cell wall hydrolases in bacteria: Insight on the diversity of cell wall amidases, glycosidases and peptidases toward peptidoglycan. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedon, E.; Serror, P.; Ehrlich, S.D.; Renault, P.; Delorme, C. Pleiotropic transcriptional repressor CodY senses the intracellular pool of branched-chain amino acids in Lactococcus lactis. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 40, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarque, M.; Charbonnel, P.; Aubel, D.; Piard, J.-C.; Atlan, D.; Juillard, V. A Multifunction ABC transporter (Opt) contributes to diversity of peptide uptake specificity within the genus Lactococcus. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 6492–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, P.D.; Hill, C. Surviving the acid test: Responses of gram-positive bacteria to low pH. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedon, E.; Sperandio, B.; Pons, N.; Ehrlich, S.D.; Renault, P. Overall control of nitrogen metabolism in Lactococcus lactis by CodY, and possible models for CodY regulation in Firmicutes. Microbiology 2005, 151, 3895–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slamti, L.; Lereclus, D. The oligopeptide ABC-importers are essential communication channels in Gram-positive bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 2019, 170, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, P.G.; Saavedra, L.; Hebert, E.M. Proteomic Signature in Lactic Acid Bacteria and Related Microorganisms. In Proteomics Applied to Foods; Ferranti, P., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Sinitcyn, P.; Carlson, A.; Hein, M.Y.; Geiger, T.; Mann, M.; Cox, J. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: The Universal Protein Resource in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D523–D531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta-Cepas, J.; Szklarczyk, D.; Heller, D.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Forslund, S.K.; Cook, H.; Mende, D.R.; Letunic, I.; Rattei, T.; Jensen, L.J.; et al. eggNOG 5.0: A hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D309–D314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakers, C.; Ruijter, J.M.; Deprez, R.H.; Moorman, A.F. Assumption-free analysis of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) data. Neurosci. Lett. 2003, 339, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Medium 1 | Specific Growth Rate (h−1) | Final Cell Density (OD 600 nm) | GABA Production (mM) | Final pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDMg | 0.20 ± 0.02 a | 1.60 ± 0.12 a | ND | 4.90 ± 0.05 c |

| CDMYE | 0.34 ± 0.02 c | 6.19 ± 0.18 d | ND | 4.69 ± 0.04 d,e |

| CDMC2 | 0.33 ± 0.02 c | 6.29 ± 0.19 d | ND | 4.68 ± 0.05 e |

| CDMgYE | 0.34 ± 0.03 c | 5.85 ± 0.22 d | 258 ± 12 a | 7.24 ± 0.05 a |

| CDMgC0.5 | 0.24 ± 0.02 a,b | 2.81 ± 0.15 b | ND | 4.93 ± 0.04 c |

| CDMgC | 0.28 ± 0.02 b | 3.55 ± 0.19 c | 156 ± 11 b | 6.11 ± 0.03 b |

| CDMgC2 | 0.33 ± 0.02 c | 6.30 ± 0.19 d | 251 ± 17 a | 7.10 ± 0.04 a |

| CDMgC5 | 0.34 ± 0.02 c | 6.35 ± 0.20 d | 255 ± 11 a | 7.15 ± 0.04 a |

| CDMgCA | 0.26 ± 0.02 a,b | 2.71 ± 0.25 b | ND | 4.85 ± 0.05 c |

| CDMgT | 0.25 ± 0.03 a,b | 2.68 ± 0.18 b | ND | 4.83 ± 0.04 c,d |

| CDMgVP | 0.26 ± 0.02 a,b | 2.81 ± 0.24 b | 15 ± 1 c | 4.87 ± 0.04 c |

| CDMgLMMP | 0.25 ± 0.02 a,b | 3.45 ± 0.28 c | 165 ± 15 b | 6.09 ± 0.04 b |

| CDMgHMMP | 0.22 ± 0. 02 a,b | 2.91 ± 0.28 b | 16 ± 3 c | 4.96 ± 0.05 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Urquiza Martínez, M.P.; Cataldo, P.G.; Ríos Colombo, N.S.; Ferranti, P.; Saavedra, L.; Hebert, E.M. Influence of Peptide-Rich Nitrogen Sources on GAD System Activation and GABA Production in Levilactobacillus brevis CRL 2013. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010082

Urquiza Martínez MP, Cataldo PG, Ríos Colombo NS, Ferranti P, Saavedra L, Hebert EM. Influence of Peptide-Rich Nitrogen Sources on GAD System Activation and GABA Production in Levilactobacillus brevis CRL 2013. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010082

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrquiza Martínez, María Paulina, Pablo G. Cataldo, Natalia Soledad Ríos Colombo, Pasquale Ferranti, Lucila Saavedra, and Elvira M. Hebert. 2026. "Influence of Peptide-Rich Nitrogen Sources on GAD System Activation and GABA Production in Levilactobacillus brevis CRL 2013" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010082

APA StyleUrquiza Martínez, M. P., Cataldo, P. G., Ríos Colombo, N. S., Ferranti, P., Saavedra, L., & Hebert, E. M. (2026). Influence of Peptide-Rich Nitrogen Sources on GAD System Activation and GABA Production in Levilactobacillus brevis CRL 2013. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010082