NO-cGMP Signaling in Endothelial Function of the Healthy and Inflamed Dental Pulp

Abstract

1. Introduction

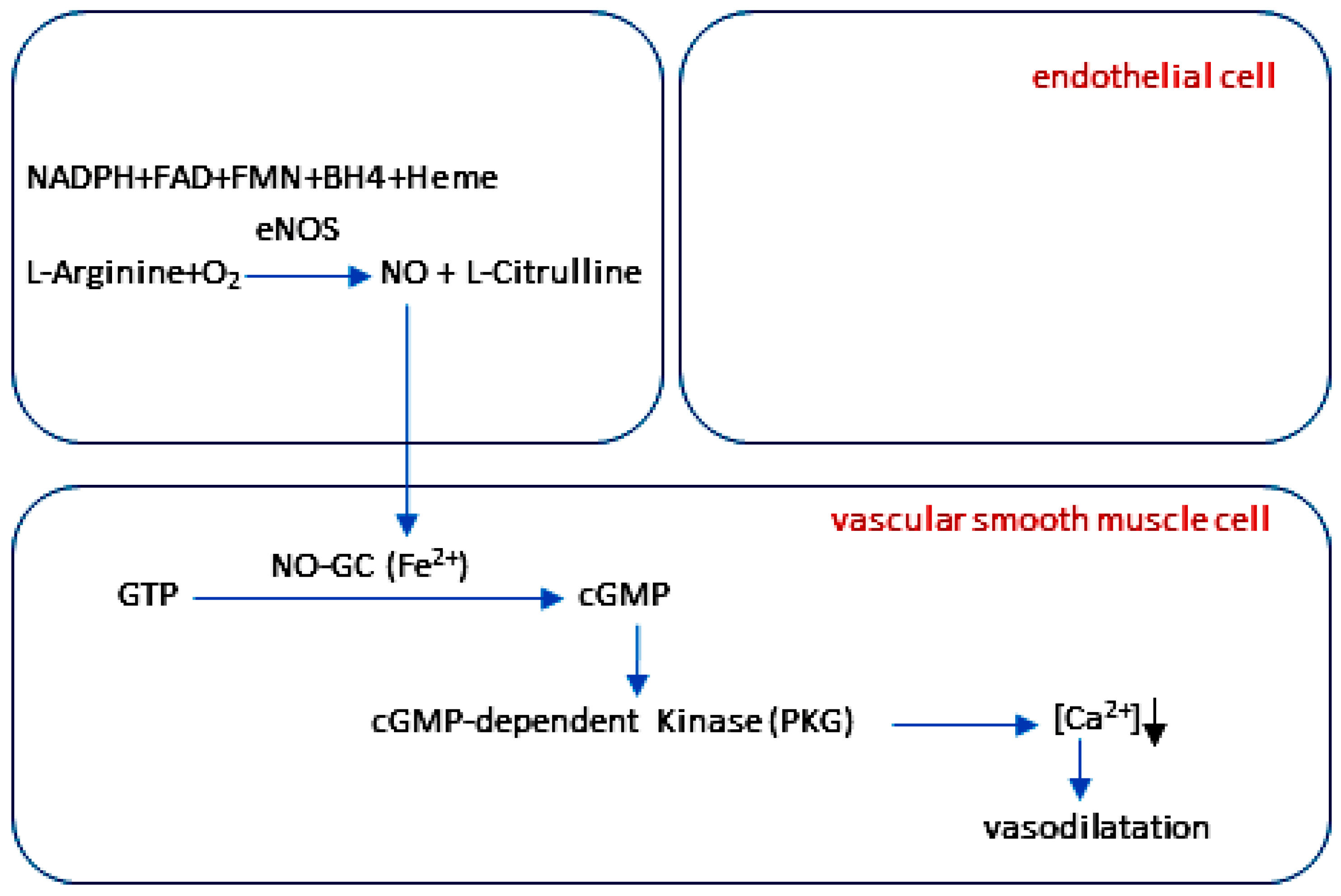

2. NO and NO-cGMP Signaling in Endothelial Function

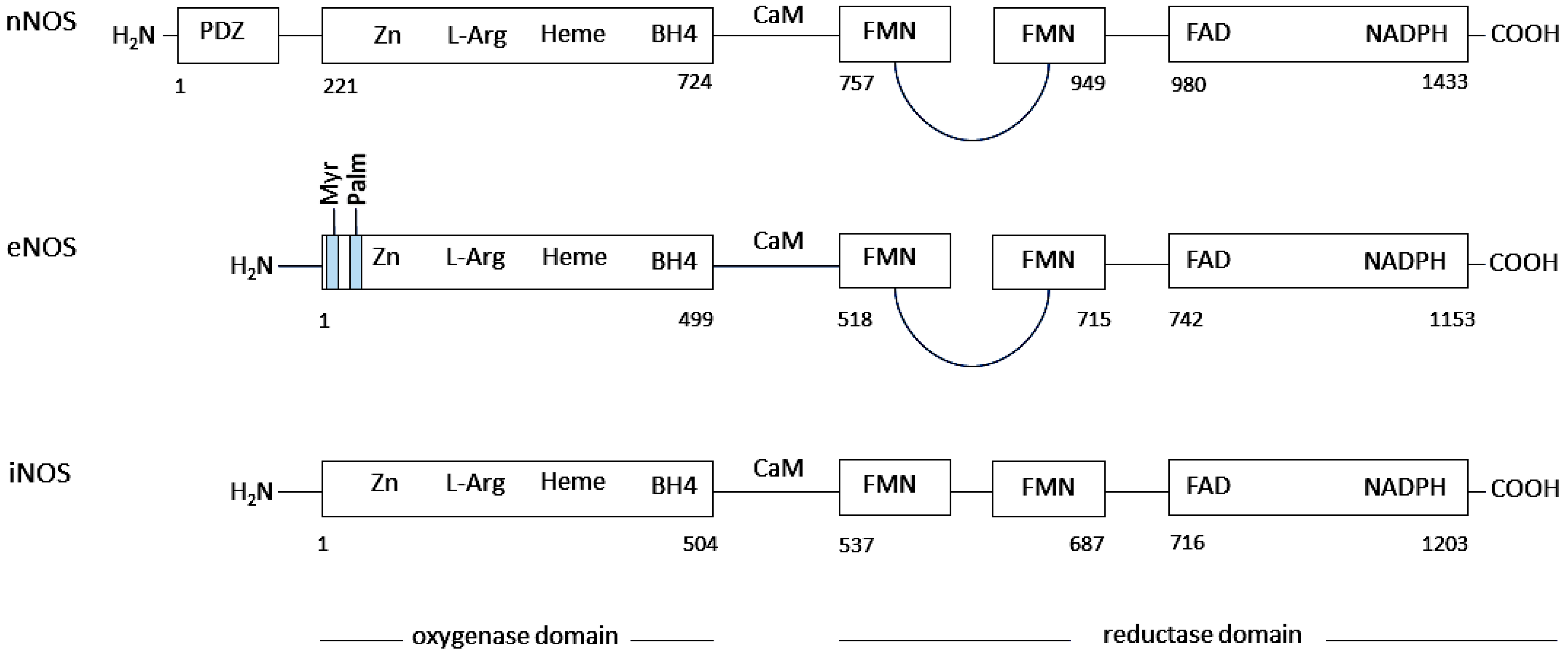

2.1. The Structure, Expression, and Regulation of Nitric Oxide Synthases

2.1.1. Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase (nNOS)

2.1.2. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase (eNOS)

2.1.3. Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS)

2.2. The Regulation of eNOS Activity in Endothelium

2.3. Structure and Maturation of NO-GC

2.3.1. The Protein Structure of NO-GC

2.3.2. The Maturation and Regulation of NO-GC Activity

2.4. The NO-cGMP Signaling Cascade in Vascular Function

3. NO and NO-cGMP Signaling in the Healthy Dental Pulp

3.1. The Healthy Dentin–Pulp Complex

3.2. The Regulation of Circulation by Intrapulpal Tissue Pressure in Healthy Dental Pulp

3.3. The Phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177 in the Endothelial Cells of Healthy Dental Pulp

3.4. NO-GC and cGMP in Blood Vessels of Healthy Dental Pulp

3.5. The Role of the NO-cGMP Signaling in Maintaining Homeostasis of Healthy Dental Pulp

4. NO and NO-cGMP Signaling in Endothelial Dysfunction

4.1. The Uncoupled eNOS

4.1.1. Uncoupled eNOS by Oxidative Depletion of Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4)

4.1.2. Uncoupled eNOS by Oxidative Disruption of the Zinc-Sulfur Complex

4.1.3. Uncoupled eNOS by Phosphorylation of Enzyme at Thr495

4.1.4. Uncoupled eNOS by S-Glutathionylation of the Enzyme at Cys689 and Cys908

4.1.5. Uncoupled eNOS by Reduced Substrate Availability

4.1.6. Uncoupled eNOS by Asymmetric Dimethyl Arginine (ADMA)

4.2. Desensitization of NO-GC to NO

4.2.1. Heme Iron Oxidation in NO-GC

4.2.2. Thiol Oxidation and S-Nitrosylation of NO-GC

5. NO and NO-cGMP Signaling in Endothelial Dysfunction of Inflamed Dental Pulp

5.1. Inflammation of the Dental Pulp

5.2. The Regulation of Circulation by Intrapulpal Tissue Pressure in Inflamed Dental Pulp

5.3. The Formation of ROS and RNS in Inflamed Dental Pulp

5.4. Uncoupled eNOS and Endothelial Dysfunction in Inflamed Dental Pulp

5.4.1. Uncoupled eNOS by Phosphorylation of eNOS at Thr495 in the Endothelial Cells of Inflamed Dental Pulp

5.4.2. The Uncoupling of eNOS Through the Oxidation of BH4 and ZnCys4 in Inflamed Dental Pulp

5.4.3. The Uncoupling of eNOS Due to Competition with iNOS for the Common Substrate L-Arginine in Inflamed Dental Pulp

5.4.4. The Uncoupling of eNOS Due to Increased Formation of the Endogenous eNOS Inhibitor ADMA in Inflamed Dental Pulp

5.5. Oxidized NO-GC and Endothelial Dysfunction in Inflamed Dental Pulp

5.6. The Critical Role of Endothelial Dysfunction in Inflammation of the Dental Pulp

6. Targeting the NO-cGMP Signaling in the Treatment of Endothelial Dysfunction in Inflamed Dental Pulp

6.1. The Significance of Endothelial Dysfunction for the Treatment of Caries

6.1.1. Dentin Matrix Formation Under Healthy and Inflammatory Conditions in the Dentin–Pulp Complex

6.1.2. The Role of Endothelial Dysfunction in the Regenerative Functions of Odontoblasts

6.2. NO as a Therapeutic Target in Endothelial Dysfunction of Inflamed Dental Pulp

6.2.1. NO Donors

6.2.2. The S-Glutathionylation of eNOS

6.2.3. BH4 Supplementation

6.3. NO-GC as a Therapeutic Target in Endothelial Dysfunction of Inflamed Dental Pulp

6.3.1. NO-GC Stimulators and Activators

NO-GC Stimulators

NO-GC Activators

6.4. Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibitors

7. Conclusions

8. Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Takahashi, K. Vascular architecture of dog pulp using corrosion resin cast examined under a scanning electron microscope. J. Dent. Res. 1985, 64, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Microcirculation of the dental pulp in health and disease. J. Endod. 1985, 11, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Ohshima, H. Distribution and organization of peripheral capillaries in dental pulp and their relationship to odontoblasts. Anat. Rec. 1996, 245, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.J. Pulpal responses to caries and dental repair. Caries Res. 2002, 36, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, P.R.; Holder, M.J.; Smith, A.J. Inflammation and regeneration in the dentin-pulp complex: A double-edged sword. J. Endod. 2014, 40, S46–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farges, J.C.; Alliot-Licht, B.; Renard, E.; Ducret, M.; Gaudin, A.; Smith, A.J.; Cooper, P.R. Dental Pulp Defence and Repair Mechanisms in Dental Caries. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 230251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.J.; Duncan, H.F.; Diogenes, A.; Simon, S.; Cooper, P.R. Exploiting the Bioactive Properties of the Dentin-Pulp Complex in Regenerative Endodontics. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Neurovascular interactions in the dental pulp in health and inflammation. J. Endod. 1990, 16, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyeraas, K.J.; Kvinnsland, I. Tissue pressure and blood flow in pulpal inflammation. Proc. Finn. Dent. Soc. 1992, 88, 393–401. [Google Scholar]

- Heyeraas, K.J.; Berggreen, E. Interstitial fluid pressure in normal and inflamed pulp. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1999, 10, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggreen, E.; Bletsa, A.; Heyeraas, K.J. Circulation in normal and inflamed dental pulp. Endod. Top. 2007, 17, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdek, Ö.; Bloch, W.; Rink-Notzon, S.; Roggendorf, H.C.; Uzun, S.; Meul, B.; Koch, M.; Neugebauer, J.; Deschner, J.; Korkmaz, Y. Inflammation of the Human Dental Pulp Induces Phosphorylation of eNOS at Thr495 in Blood Vessels. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhoutte, P.M.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, A.; Leung, S.W. Thirty Years of Saying NO: Sources, Fate, Actions, and Misfortunes of the Endothelium-Derived Vasodilator Mediator. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutterman, D.D.; Chabowski, D.S.; Kadlec, A.O.; Durand, M.J.; Freed, J.K.; Ait-Aissa, K.; Beyer, A.M. The Human Microcirculation: Regulation of Flow and Beyond. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oates, J.C.; Russell, D.L.; Van Beusecum, J.P. Endothelial cells: Potential novel regulators of renal inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2022, 322, F309–F321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.N.; Garthwaite, J. What is the real physiological NO concentration in vivo? Nitric Oxide 2009, 21, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friebe, A.; Koesling, D. Regulation of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase. Circ. Res. 2003, 93, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murad; Shattuck Lecture, F. Nitric oxide and cyclic GMP in cell signaling and drug development. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2003–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncada, S.; Higgs, A. The L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 329, 2002–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loscalzo, J. Nitric oxide insufficiency, platelet activation, and arterial thrombosis. Circ. Res. 2001, 88, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangel, O.; Mergia, E.; Karlisch, K.; Groneberg, D.; Koesling, D.; Friebe, A. Nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase is the only nitric oxide receptor mediating platelet inhibition. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 1343–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhoul, S.; Walter, E.; Pagel, O.; Walter, U.; Sickmann, A.; Gambaryan, S.; Smolenski, A.; Zahedi, R.P.; Jurk, K. Effects of the NO/soluble guanylate cyclase/cGMP system on the functions of human platelets. Nitric Oxide 2018, 76, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauersberger, C.; Sager, H.B.; Wobst, J.; Dang, T.A.; Lambrecht, L.; Koplev, S.; Stroth, M.; Bettaga, N.; Schlossmann, J.; Wunder, F.; et al. Loss of soluble guanylyl cyclase in platelets contributes to atherosclerotic plaque formation and vascular inflammation. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 1, 1174–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sneddon, J.M.; Vane, J.R. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor reduces platelet adhesion to bovine endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 2800–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radomski, M.W.; Palmer, R.M.; Moncada, S. An L-arginine/nitric oxide pathway present in human platelets regulates aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 5193–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahluwalia, A.; Foster, P.; Scotland, R.S.; McLean, P.G.; Mathur, A.; Perretti, M.; Moncada, S.; Hobbs, A.J. Antiinflammatory activity of soluble guanylate cyclase: cGMP-dependent down-regulation of P-selectin expression and leukocyte recruitment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 1386–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimbrone, M.A., Jr.; García-Cardeña, G. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and the Pathobiology of Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, U.C.; Hassid, A. Nitric oxide-generating vasodilators and 8-bromo-cyclic guanosine monophosphate inhibit mitogenesis and proliferation of cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Clin. Investig. 1989, 83, 1774–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudic, R.D.; Shesely, E.G.; Maeda, N.; Smithies, O.; Segal, S.S.; Sessa, W.C. Direct evidence for the importance of endothelium-derived nitric oxide in vascular remodeling. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, C.; Paolisso, G.; Casamassimi, A.; Al-Omran, M.; Barbieri, M.; Sommese, L.; Infante, T.; Ignarro, L.J. Effects of nitric oxide on cell proliferation: Novel insights. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, S.; Ibrahim, M.; Schlitzer, A.; Maegdefessel, L.; Röll, W.; Pfeifer, A. PDGF regulates guanylate cyclase expression and cGMP signaling in vascular smooth muscle. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 197, Erratum in Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 298. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03244-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Daiber, A.; Ullrich, V.; Mülsch, A. Vascular consequences of endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling for the activity and expression of the soluble guanylyl cyclase and the cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasch, J.P.; Pacher, P.; Evgenov, O.V. Soluble guanylate cyclase as an emerging therapeutic target in cardiopulmonary disease. Circulation 2011, 123, 2263–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Gladwin, M.T.; Weitzberg, E. Strategies to increase nitric oxide signalling in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandner, P.; Stasch, J.P. Anti-fibrotic effects of soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators and activators: A review of the preclinical evidence. Respir. Med. 2017, 122, S1–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandner, P.; Zimmer, D.P.; Milne, G.T.; Follmann, M.; Hobbs, A.; Stasch, J.P. Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulators and Activators. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2021, 264, 355–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daiber, A.; Chlopicki, S. Revisiting pharmacology of oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease: Evidence for redox-based therapies. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 157, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, M. Structure, regulation, and function of mammalian membrane guanylyl cyclase receptors, with a focus on guanylyl cyclase-A. Circ. Res. 2003, 93, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M. Molecular Physiology of Membrane Guanylyl Cyclase Receptors. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 751–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, L.R.; Verde, I.; Cooper, D.M.; Fischmeister, R. Cyclic guanosine monophosphate compartmentation in rat cardiac myocytes. Circulation 2006, 113, 2221–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takimoto, E.; Belardi, D.; Tocchetti, C.G.; Vahebi, S.; Cormaci, G.; Ketner, E.A.; Moens, A.L.; Champion, H.C.; Kass, D.A. Compartmentalization of cardiac β-adrenergic inotropy modulation by phosphodiesterase type 5. Circulation 2007, 115, 2159–2167, Erratum in Circulation 2007, 115, e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.L.; Lam, C.S.; Segers, V.F.; Brutsaert, D.L.; De Keulenaer, G.W. Cardiac endothelium-myocyte interaction: Clinical opportunities for new heart failure therapies regardless of ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 2050–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Förstermann, U.; Closs, E.I.; Pollock, J.S.; Nakane, M.; Schwarz, P.; Gath, I.; Kleinert, H. Nitric oxide synthase isozymes. Characterization, purification, molecular cloning, and functions. Hypertension 1994, 23, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuehr, D.J. Mammalian nitric oxide synthases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1411, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderton, W.K.; Cooper, C.E.; Knowles, R.G. Nitric oxide synthases: Structure, function and inhibition. Biochem. J. 2001, 357, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daff, S. NO synthase: Structures and mechanisms. Nitric Oxide 2010, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthases: Regulation and function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837, 837a–837d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, I. Molecular mechanisms underlying the activation of eNOS. Pflug. Arch. 2010, 459, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero, J.; Shiva, S.; Gladwin, M.T. Sources of Vascular Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 311–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Münzel, T. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular disease: From marvel to menace. Circulation 2006, 113, 1708–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Forstermann, U. Pharmacological prevention of eNOS uncoupling. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 3595–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Chander, V.; Kass, D.A. Cardiac cGMP Regulation and Therapeutic Applications. Hypertension 2025, 82, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farah, C.; Michel, L.Y.M.; Balligand, J.L. Nitric oxide signalling in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 292–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feron, O.; Michel, J.B.; Sase, K.; Michel, T. Dynamic regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: Complementary roles of dual acylation and caveolin interactions. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhassen, L.; Feron, O.; Kaye, D.M.; Michel, T.; Kelly, R.A. Regulation by cAMP of post-translational processing and subcellular targeting of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (type 3) in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 11198–11204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cardeña, G.; Oh, P.; Liu, J.; Schnitzer, J.E.; Sessa, W.C. Targeting of nitric oxide synthase to endothelial cell caveolae via palmitoylation: Implications for nitric oxide signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 6448–6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissel, J.-P.; Schwarz, P.M.; Förstermann, U. Neuronal-Type NO Synthase: Transcript Diversity and Expressional Regulation. Nitric Oxide 1998, 2, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Zhu, D.Y. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase: Structure, subcellular localization, regulation, and clinical implications. Nitric Oxide 2009, 20, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredt, D.S.; Hwang, P.M.; Snyder, S.H. Localization of nitric oxide synthase indicating a neural role for nitric oxide. Nature 1990, 347, 768–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredt, D.S.; Glatt, C.E.; Hwang, P.M.; Fotuhi, M.; Dawson, T.M.; Snyder, S.H. Nitric oxide synthase protein and mRNA are discretely localized in neuronal populations of the mammalian CNS together with NADPH diaphorase. Neuron 1991, 7, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, M.J.; Li, C.G. Nitric oxide as a neurotransmitter in peripheral nerves: Nature of transmitter and mechanism of transmission. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1995, 57, 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, P.; Alm, P.; Andersson, K.E. NO synthase in cholinergic nerves and NO-induced relaxation in the rat isolated corpus cavernosum. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 127, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, C.M.; Heymes, C.; Benessiano, J.; Geske, R.S.; Levy, B.I.; Vanhoutte, P.M. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase is expressed in rat vascular smooth muscle cells: Activation by angiotensin II in hypertension. Circ. Res. 1998, 83, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, P.M.; Kleinert, H.; Förstermann, U. Potential functional significance of brain-type and muscle-type nitric oxide synthase I expressed in adventitia and media of rat aorta. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999, 19, 2584–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakane, M.; Schmidt, H.H.; Pollock, J.S.; Förstermann, U.; Murad, F. Cloned human brain nitric oxide synthase is highly expressed in skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1993, 316, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobzik, L.; Reid, M.B.; Bredt, D.S.; Stamler, J.S. Nitric oxide in skeletal muscle. Nature 1994, 372, 546–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamler, J.S.; Meissner, G. Physiology of nitric oxide in skeletal muscle. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 209–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothe, F.; Langnaese, K.; Wolf, G. New aspects of the location of neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the skeletal muscle: A light and electron microscopic study. Nitric Oxide 2005, 13, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, Y.; Clifford, D.B.; Zorumski, C.F. Inhibition of long-term potentiation by NMDA-mediated nitric oxide release. Science 1992, 257, 1273–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, Y.; Zorumski, C.F. Nitric oxide and long-term synaptic depression in the rat hippocampus. Neuroreport 1993, 4, 1131–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Bredt, D.S.; Snyder, S.H. Nitric oxide, a novel neuronal messenger. Neuron 1992, 8, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, V.; Mancuso, C.; Calvani, M.; Rizzarelli, E.; Butterfield, D.A.; Stella, A.M. Nitric oxide in the central nervous system: Neuroprotection versus neurotoxicity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garthwaite, J. Concepts of neural nitric oxide-mediated transmission. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008, 27, 2783–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredt, D.S. Endogenous nitric oxide synthesis: Biological functions and pathophysiology. Free Radic. Res. 1999, 31, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melikian, N.; Seddon, M.D.; Casadei, B.; Chowienczyk, P.J.; Shah, A.M. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase and human vascular regulation. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2009, 19, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.; Azadzoi, K.M.; Goldstein, I.; Saenz de Tejada, I. A nitric oxide-like factor mediates nonadrenergic-noncholinergic neurogenic relaxation of penile corpus cavernosum smooth muscle. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 88, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajfer, J.; Aronson, W.J.; Bush, P.A.; Dorey, F.J.; Ignarro, L.J. Nitric oxide as a mediator of relaxation of the corpus cavernosum in response to nonadrenergic, noncholinergic neurotransmission. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 326, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, N.; Okamura, T. The pharmacology of nitric oxide in the peripheral nervous system of blood vessels. Pharmacol. Rev. 2003, 55, 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, N.; Ayajiki, K.; Okamura, T. Nitric oxide and penile erectile function. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 106, 233–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, P.A.; Heng, H.H.; Scherer, S.W.; Stewart, R.J.; Hall, A.V.; Shi, X.M.; Tsui, L.C.; Schappert, K.T. Structure and chromosomal localization of the human constitutive endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 17478–17488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignarro, L.J.; Byrns, R.E.; Buga, G.M.; Wood, K.S. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor from pulmonary artery and vein possesses pharmacologic and chemical properties identical to those of nitric oxide radical. Circ. Res. 1987, 61, 866–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, R.M.; Ferrige, A.G.; Moncada, S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature 1987, 327, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncada, S.; Palmer, R.M.; Higgs, E.A. The discovery of nitric oxide as the endogenous nitrovasodilator. Hypertension 1988, 12, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forstermann, U.; Pollock, J.S.; Schmidt, H.H.; Heller, M.; Murad, F. Calmodulin-dependent endothelium-derived relaxing factor/nitric oxide synthase activity is present in the particulate and cytosolic fractions of bovine aortic endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 1788–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, R.M.; Draznin, M.B.; Murad, F. Endothelium-dependent relaxation in rat aorta may be mediated through cyclic GMP-dependent protein phosphorylation. Nature 1983, 306, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furchgott, R.F.; Cherry, P.D.; Zawadzki, J.V.; Jothianandan, D. Endothelial cells as mediators of vasodilation of arteries. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1984, 6, S336–S343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Mülsch, A.; Böhme, E.; Busse, R. Stimulation of soluble guanylate cyclase by an acetylcholine-induced endothelium-derived factor from rabbit and canine arteries. Circ. Res. 1986, 58, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murohara, T.; Witzenbichler, B.; Spyridopoulos, I.; Asahara, T.; Ding, B.; Sullivan, A.; Losordo, D.W.; Isner, J.M. Role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cell migration. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999, 19, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbach, S.; Wenzel, P.; Waisman, A.; Munzel, T.; Daiber, A. eNOS uncoupling in cardiovascular diseases—The role of oxidative stress and inflammation. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 3579–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiber, A.; Steven, S.; Weber, A.; Shuvaev, V.V.; Muzykantov, V.R.; Laher, I.; Li, H.; Lamas, S.; Münzel, T. Targeting vascular (endothelial) dysfunction. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1591–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuehr, D.J.; Cho, H.J.; Kwon, N.S.; Weise, M.F.; Nathan, C.F. Purification and characterization of the cytokine-induced macrophage nitric oxide synthase: An FAD- and FMN-containing flavoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 7773–7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, C.; Xie, Q.W. Nitric oxide synthases: Roles, tolls, and controls. Cell 1994, 78, 915–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.W.; Kashiwabara, Y.; Nathan, C. Role of transcription factor NF-kappa B/Rel in induction of nitric oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 4705–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vera, M.E.; Shapiro, R.A.; Nussler, A.K.; Mudgett, J.S.; Simmons, R.L.; Morris, S.M., Jr.; Billiar, T.R.; Geller, D.A. Transcriptional regulation of human inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) gene by cytokines: Initial analysis of the human NOS2 promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pautz, A.; Art, J.; Hahn, S.; Nowag, S.; Voss, C.; Kleinert, H. Regulation of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Nitric Oxide 2010, 23, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balligand, J.L.; Ungureanu-Longrois, D.; Simmons, W.W.; Pimental, D.; Malinski, T.A.; Kapturczak, M.; Taha, Z.; Lowenstein, C.J.; Davidoff, A.J.; Kelly, R.A.; et al. Cytokine-inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression in cardiac myocytes. Characterization and regulation of iNOS expression and detection of iNOS activity in single cardiac myocytes in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 27580–27588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haywood, G.A.; Tsao, P.S.; von der Leyen, H.E.; Mann, M.J.; Keeling, P.J.; Trindade, P.T.; Lewis, N.P.; Byrne, C.D.; Rickenbacher, P.R.; Bishopric, N.H.; et al. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in human heart failure. Circulation 1996, 93, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, J.N.; Subramanian, R.R.; Sundell, C.L.; Tracey, W.R.; Pollock, J.S.; Harrison, D.G.; Marsden, P.A. Expression of multiple isoforms of nitric oxide synthase in normal and atherosclerotic vessels. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997, 17, 2479–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMicking, J.; Xie, Q.W.; Nathan, C. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997, 15, 323–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zweier, J.L. Superoxide and peroxynitrite generation from inducible nitric oxide synthase in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 6954–6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.A.; Do, H.T.; Miley, G.P.; Silverman, R.B. Inducible nitric oxide synthase: Regulation, structure, and inhibition. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 158–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billaud, M.; Lohman, A.W.; Johnstone, S.R.; Biwer, L.A.; Mutchler, S.; Isakson, B.E. Regulation of cellular communication by signaling microdomains in the blood vessel wall. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014, 66, 513–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, P.G.; Woodman, S.E.; Park, D.S.; Lisanti, M.P. Caveolin, caveolae, and endothelial cell function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratton, J.P.; Bernatchez, P.; Sessa, W.C. Caveolae and caveolins in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, J.; Fulton, D.; Chen, Y.; Fairchild, T.A.; McCabe, T.J.; Fujita, N.; Tsuruo, T.; Sessa, W.C. Domain mapping studies reveal that the M domain of hsp90 serves as a molecular scaffold to regulate Akt-dependent phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and NO release. Circ. Res. 2002, 90, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balligand, J.L.; Feron, O.; Dessy, C. eNOS activation by physical forces: From short-term regulation of contraction to chronic remodeling of cardiovascular tissues. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 481–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimmeler, S.; Fleming, I.; Fisslthaler, B.; Hermann, C.; Busse, R.; Zeiher, A.M. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature 1999, 399, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, I.; Busse, R. Molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2003, 284, R1–R12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evgenov, O.V.; Pacher, P.; Schmidt, P.M.; Haskó, G.; Schmidt, H.H.; Stasch, J.P. NO-independent stimulators and activators of soluble guanylate cyclase: Discovery and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friebe, A.; Koesling, D. The function of NO-sensitive guanylyl cyclase: What we can learn from genetic mouse models. Nitric Oxide 2009, 21, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.C.; Sanker, S.; Wood, K.C.; Durgin, B.G.; Straub, A.C. Redox regulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Nitric Oxide 2018, 76, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabel, U.; Häusler, C.; Weeger, M.; Schmidt, H.H. Homodimerization of soluble guanylyl cyclase subunits. Dimerization analysis using a glutathione s-transferase affinity tag. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 18149–18152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernhoff, N.B.; Derbyshire, E.R.; Marletta, M.A. A nitric oxide/cysteine interaction mediates the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21602–21607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, M.R.; DeMartino, A.W.; Tejero, J.; Gladwin, M.T. Endogenous Hemoprotein-Dependent Signaling Pathways of Nitric Oxide and Nitrite. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 15918–15940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharina, I.G.; Krumenacker, J.S.; Martin, E.; Murad, F. Genomic organization of α1 and β1 subunits of the mammalian soluble guanylyl cyclase genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 10878–10883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharina, I.G.; Cote, G.J.; Martin, E.; Doursout, M.F.; Murad, F. RNA splicing in regulation of nitric oxide receptor soluble guanylyl cyclase. Nitric Oxide 2011, 25, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, B.J.; Garthwaite, J. Subunits of the nitric oxide receptor, soluble guanylyl cyclase, expressed in rat brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001, 13, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, T.C.; Garthwaite, J. Pharmacology of the nitric oxide receptor, soluble guanylyl cyclase, in cerebellar cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 136, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friebe, A.; Voußen, B.; Groneberg, D. NO-GC in cells ‘off the beaten track’. Nitric Oxide 2018, 77, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, Y.; Pryymachuk, G.; Schroeter, M.M.; Puladi, B.; Piekarek, N.; Appel, S.; Bloch, W.; Lackmann, J.W.; Deschner, J.; Friebe, A. The α1- and β1-Subunits of Nitric Oxide-Sensitive Guanylyl Cyclase in Pericytes of Healthy Human Dental Pulp. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 26, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergia, E.; Russwurm, M.; Zoidl, G.; Koesling, D. Major occurrence of the new α2β1 isoform of NO-sensitive guanylyl cyclase in brain. Cell. Signal. 2003, 15, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, Y.; Baumann, M.A.; Steinritz, D.; Schröder, H.; Behrends, S.; Addicks, K.; Schneider, K.; Raab, W.H.; Bloch, W. NO-cGMP signaling molecules in cells of the rat molar dentin-pulp complex. J. Dent. Res. 2005, 84, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koesling, D.; Mergia, E.; Russwurm, M. Physiological Functions of NO-Sensitive Guanylyl Cyclase Isoforms. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 2653–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, P.S.; Potter, L.R.; Garbers, D.L. A new form of guanylyl cyclase is preferentially expressed in rat kidney. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 10872–10878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrends, S.; Budaeus, L.; Kempfert, J.; Scholz, H.; Starbatty, J.; Vehse, K. The β2 subunit of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase is developmentally regulated in rat kidney. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2001, 364, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, G.; Azam, M.; Yang, L.; Danziger, R.S. The β2 subunit inhibits stimulation of the α1/β1 form of soluble guanylyl cyclase by nitric oxide. Potential relevance to regulation of blood pressure. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 1488–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelissen, E.; Schepers, M.; Ponsaerts, L.; Foulquier, S.; Bronckaers, A.; Vanmierlo, T.; Sandner, P.; Prickaerts, J. Soluble guanylyl cyclase: A novel target for the treatment of vascular cognitive impairment? Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 197, 106970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K.A.; Pitari, G.M.; Kazerounian, S.; Ruiz-Stewart, I.; Park, J.; Schulz, S.; Chepenik, K.P.; Waldman, S.A. Guanylyl cyclases and signaling by cyclic GMP. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000, 52, 375–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derbyshire, E.R.; Marletta, M.A. Structure and regulation of soluble guanylate cyclase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012, 81, 533–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuve, A. Thiol-Based Redox Modulation of Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase, the Nitric Oxide Receptor. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 26, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Liu, R.; Wu, J.X.; Chen, L. Structural insights into the mechanism of human soluble guanylate cyclase. Nature 2019, 574, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montfort, W.R.; Wales, J.A.; Weichsel, A. Structure and Activation of Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase, the Nitric Oxide Sensor. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 26, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, B.G.; Marletta, M.A. Physiological activation and deactivation of soluble guanylate cyclase. Nitric Oxide 2018, 77, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burette, A.; Zabel, U.; Weinberg, R.J.; Schmidt, H.H.; Valtschanoff, J.G. Synaptic localization of nitric oxide synthase and soluble guanylyl cyclase in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 8961–8970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budworth, J.; Meillerais, S.; Charles, I.; Powell, K. Tissue distribution of the human soluble guanylate cyclases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 263, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuehr, D.J.; Biswas, P.; Dai, Y.; Ghosh, A.; Islam, S.; Jayaram, D.T. A natural heme deficiency exists in biology that allows nitric oxide to control heme protein functions by regulating cellular heme distribution. Bioessays 2023, 45, e2300055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Stuehr, D.J. Heme delivery into soluble guanylyl cyclase requires a heme redox change and is regulated by NO and Hsp90 by distinct mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Faul, E.M.; Ghosh, A.; Stuehr, D.J. NO rapidly mobilizes cellular heme to trigger assembly of its own receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2115774119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagöz, G.E.; Rüdiger, S.G. Hsp90 interaction with clients. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Stasch, J.P.; Papapetropoulos, A.; Stuehr, D.J. Nitric oxide and heat shock protein 90 activate soluble guanylate cyclase by driving rapid change in its subunit interactions and heme content. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 15259–15271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Schlanger, S.; Haque, M.M.; Misra, S.; Stuehr, D.J. Heat shock protein 90 regulates soluble guanylyl cyclase maturation by a dual mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 12880–12891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Sweeny, E.A.; Schlanger, S.; Ghosh, A.; Stuehr, D.J. GAPDH delivers heme to soluble guanylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 8145–8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeny, E.A.; Schlanger, S.; Stuehr, D.J. Dynamic regulation of NADPH oxidase 5 by intracellular heme levels and cellular chaperones. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuehr, D.J.; Misra, S.; Dai, Y.; Ghosh, A. Maturation, inactivation, and recovery mechanisms of soluble guanylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y. The multiple actions of NO. Pflug. Arch. 2010, 459, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, W.P.; Mittal, C.K.; Katsuki, S.; Murad, F. Nitric oxide activates guanylate cyclase and increases guanosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate levels in various tissue preparations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 3203–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldman, S.A.; Murad, F. Cyclic GMP synthesis and function. Pharmacol. Rev. 1987, 39, 163–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, F. The biology of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biel, M.; Sautter, A.; Ludwig, A.; Hofmann, F.; Zong, X. Cyclic nucleotide-gated channels--mediators of NO:cGMP-regulated processes. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 1998, 358, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischmeister, R.; Castro, L.; Abi-Gerges, A.; Rochais, F.; Vandecasteele, G. Species- and tissue-dependent effects of NO and cyclic GMP on cardiac ion channels. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2005, 142, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybalkin, S.D.; Yan, C.; Bornfeldt, K.E.; Beavo, J.A. Cyclic GMP phosphodiesterases and regulation of smooth muscle function. Circ. Res. 2003, 93, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmesser, U.; Hornig, B.; Drexler, H. Endothelial function: A critical determinant in atherosclerosis? Circulation 2004, 109, II27–II33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magloire, H.; Romeas, A.; Melin, M.; Couble, M.L.; Bleicher, F.; Farges, J.C. Molecular regulation of odontoblast activity under dentin injury. Adv. Dent. Res. 2001, 15, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleicher, F. Odontoblast physiology. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 325, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmilewsky, F.; About, I.; Chung, S.H. Pulp Fibroblasts Control Nerve Regeneration through Complement Activation. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Vásquez, J.L.; Castañeda-Alvarado, C.P. Dental Pulp Fibroblast: A Star Cell. J. Endod. 2022, 48, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, M.R. Dental sensory receptors. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 1984, 25, 39–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, M.R.; Närhi, M.V. Dental injury models: Experimental tools for understanding neuroinflammatory interactions and polymodal nociceptor functions. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1999, 10, 4–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaukua, N.; Shahidi, M.K.; Konstantinidou, C.; Dyachuk, V.; Kaucka, M.; Furlan, A.; An, Z.; Wang, L.; Hultman, I.; Ahrlund-Richter, L.; et al. Glial origin of mesenchymal stem cells in a tooth model system. Nature 2014, 513, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Y.; Otsuka, H.; Yanagisawa, N.; Hisamitsu, H.; Manabe, A.; Nonaka, N.; Nakamura, M. In situ proliferation and differentiation of macrophages in dental pulp. Cell Tissue Res. 2011, 346, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshiba, N.; Edanami, N.; Ohkura, N.; Maekawa, T.; Takahashi, N.; Tohma, A.; Izumi, K.; Maeda, T.; Hosoya, A.; Nakamura, H.; et al. M2 Phenotype Macrophages Colocalize with Schwann Cells in Human Dental Pulp. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhingare, A.C.; Ohno, T.; Tomura, M.; Zhang, C.; Aramaki, O.; Otsuki, M.; Tagami, J.; Azuma, M. Dental pulp dendritic cells migrate to regional lymph nodes. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, Y.; Imhof, T.; Kämmerer, P.W.; Bloch, W.; Rink-Notzon, S.; Möst, T.; Weber, M.; Kesting, M.; Galler, K.M.; Deschner, J. The colocalizations of pulp neural stem cells markers with dentin matrix protein-1, dentin sialoprotein and dentin phosphoprotein in human denticle (pulp stone) lining cells. Ann. Anat. 2022, 239, 151815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronthos, S.; Mankani, M.; Brahim, J.; Robey, P.G.; Shi, S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13625–13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronthos, S.; Brahim, J.; Li, W.; Fisher, L.W.; Cherman, N.; Boyde, A.; DenBesten, P.; Robey, P.G.; Shi, S. Stem cell properties of human dental pulp stem cells. J. Dent. Res. 2002, 81, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, P.T. Neural crest and tooth morphogenesis. Adv. Dent. Res. 2001, 15, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, P.T. Dental mesenchymal stem cells. Development 2016, 143, 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, P.R.; Takahashi, Y.; Graham, L.W.; Simon, S.; Imazato, S.; Smith, A.J. Inflammation-regeneration interplay in the dentine-pulp complex. J. Dent. 2010, 38, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Song, M.; Kim, E.; Shon, W.; Chugal, N.; Bogen, G.; Lin, L.; Kim, R.H.; Park, N.H.; Kang, M.K. Pulp-dentin Regeneration: Current State and Future Prospects. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 1544–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, P.R.; Chicca, I.J.; Holder, M.J.; Milward, M.R. Inflammation and Regeneration in the Dentin-pulp Complex: Net Gain or Net Loss? J. Endod. 2017, 43, S87–S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Shen, Z.; Zhan, P.; Yang, J.; Huang, Q.; Huang, S.; Chen, L.; Lin, Z. Functional Dental Pulp Regeneration: Basic Research and Clinical Translation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hassel, H.J. Reprint of: Physiology of the Human Dental Pulp. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, J.D.; Schwartz, M.A. Vascular Mechanobiology: Homeostasis, Adaptation, and Disease. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 23, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.J.; Frye, H.; Ramanathan, R.; Caggiano, L.R.; Tabima, D.M.; Chesler, N.C.; Philip, J.L. Biomechanical and Mechanobiological Drivers of the Transition From PostCapillary Pulmonary Hypertension to Combined Pre-/PostCapillary Pulmonary Hypertension. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e028121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonder, K.J. Vascular reactions in the dental pulp during inflammation. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1983, 41, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felaco, M.; Di Maio, F.D.; De Fazio, P.; D’Arcangelo, C.; De Lutiis, M.A.; Varvara, G.; Grilli, A.; Barbacane, R.C.; Reale, M.; Conti, P. Localization of the e-NOS enzyme in endothelial cells and odontoblasts of healthy human dental pulp. Life Sci. 2000, 68, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo Di Maio, F.; Lohinai, Z.; D’Arcangelo, C.; De Fazio, P.E.; Speranza, L.; De Lutiis, M.A.; Patruno, A.; Grilli, A.; Felaco, M. Nitric oxide synthase in healthy and inflamed human dental pulp. J. Dent. Res. 2004, 83, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafea, R.; Siragusa, M.; Fleming, I. The Ever-Expanding Influence of the Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2025, 136, e70029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay-Salit, A.; Shushy, M.; Wolfovitz, E.; Yahav, H.; Breviario, F.; Dejana, E.; Resnick, N. VEGF receptor 2 and the adherens junction as a mechanical transducer in vascular endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 9462–9467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieminski, A.L.; Hebbel, R.P.; Gooch, K.J. The relative magnitudes of endothelial force generation and matrix stiffness modulate capillary morphogenesis in vitro. Exp. Cell Res. 2004, 297, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, Y.; Plomann, M.; Puladi, B.; Demirbas, A.; Bloch, W.; Deschner, J. Dental Pulp Inflammation Initiates the Occurrence of Mast Cells Expressing the α(1) and β(1) Subunits of Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietadisorn, R.; Juni, R.P.; Moens, A.L. Tackling endothelial dysfunction by modulating NOS uncoupling: New insights into its pathogenesis and therapeutic possibilities. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 302, E481–E495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Belousov, V.V.; Chandel, N.S.; Davies, M.J.; Jones, D.P.; Mann, G.E.; Murphy, M.P.; Yamamoto, M.; Winterbourn, C. Defining roles of specific reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cell biology and physiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Sinning, C.; Post, F.; Warnholtz, A.; Schulz, E. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and prognostic implications of endothelial dysfunction. Ann. Med. 2008, 40, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griendling, K.K.; Touyz, R.M.; Zweier, J.L.; Dikalov, S.; Chilian, W.; Chen, Y.R.; Harrison, D.G.; Bhatnagar, A. Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species, Reactive Nitrogen Species, and Redox-Dependent Signaling in the Cardiovascular System: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, e39–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzkaya, N.; Weissmann, N.; Harrison, D.G.; Dikalov, S. Interactions of peroxynitrite, tetrahydrobiopterin, ascorbic acid, and thiols: Implications for uncoupling endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 22546–22554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.H.; Shi, C.; Cohen, R.A. Oxidation of the zinc-thiolate complex and uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by peroxynitrite. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 109, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, I.; Fisslthaler, B.; Dimmeler, S.; Kemp, B.E.; Busse, R. Phosphorylation of Thr495 regulates Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Circ. Res. 2001, 88, E68–E75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.I.; Fulton, D.; Babbitt, R.; Fleming, I.; Busse, R.; Pritchard, K.A., Jr.; Sessa, W.C. Phosphorylation of threonine 497 in endothelial nitric-oxide synthase coordinates the coupling of L-arginine metabolism to efficient nitric oxide production. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 44719–44726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.A.; Wang, T.Y.; Varadharaj, S.; Reyes, L.A.; Hemann, C.; Talukder, M.A.; Chen, Y.R.; Druhan, L.J.; Zweier, J.L. S-glutathionylation uncouples eNOS and regulates its cellular and vascular function. Nature 2010, 468, 1115–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweier, J.L.; Chen, C.A.; Druhan, L.J. S-glutathionylation reshapes our understanding of endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and nitric oxide/reactive oxygen species-mediated signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 1769–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode-Böger, S.M.; Scalera, F.; Ignarro, L.J. The L-arginine paradox: Importance of the L-arginine/asymmetrical dimethylarginine ratio. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 114, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydow, K.; Münzel, T. ADMA and oxidative stress. Atheroscler. Suppl. 2003, 4, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böger, R.H. Association of asymmetric dimethylarginine and endothelial dysfunction. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2003, 41, 1467–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, N.J.; Channon, K.M. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by tetrahydrobiopterin in vascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katusic, Z.S.; d’Uscio, L.V. Tetrahydrobiopterin: Mediator of endothelial protection. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 397–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, A.L.; Kass, D.A. Tetrahydrobiopterin and cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 2439–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wu, Y.; Song, P.; Zhang, M.; Wang, S.; Zou, M.H. Proteasome-dependent degradation of guanosine 5′-triphosphate cyclohydrolase I causes tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency in diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2007, 116, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiber, A.; Steven, S.; Vujacic-Mirski, K.; Kalinovic, S.; Oelze, M.; Di Lisa, F.; Münzel, T. Regulation of Vascular Function and Inflammation via Cross Talk of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species from Mitochondria or NADPH Oxidase-Implications for Diabetes Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmesser, U.; Dikalov, S.; Price, S.R.; McCann, L.; Fukai, T.; Holland, S.M.; Mitch, W.E.; Harrison, D.G. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Song, P.; Zou, M.H. Tyrosine nitration of PA700 activates the 26S proteasome to induce endothelial dysfunction in mice with angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension 2009, 54, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Förstermann, U. Uncoupling of endothelial NO synthase in atherosclerosis and vascular disease. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2013, 13, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.F.; Tsai, A.L.; Wu, K.K. Cysteine 99 of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS-III) is critical for tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent NOS-III stability and activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 215, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielis, J.F.; Lin, J.Y.; Wingler, K.; Van Schil, P.E.; Schmidt, H.H.; Moens, A.L. Pathogenetic role of eNOS uncoupling in cardiopulmonary disorders. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 50, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Förstermann, U.; Xia, N.; Kuntic, M.; Münzel, T.; Daiber, A. Pharmacological targeting of endothelial nitric oxide synthase dysfunction and nitric oxide replacement therapy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 237, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.A.; De Pascali, F.; Basye, A.; Hemann, C.; Zweier, J.L. Redox modulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by glutaredoxin-1 through reversible oxidative post-translational modification. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 6712–6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meininger, C.J.; Hawker, J.R., Jr.; Haynes, T.E.; Kepka-Lenhart, D.; Mistry, S.K.; Morris, S.M., Jr.; Wu, G. Regulatory role of arginase I and II in nitric oxide, polyamine, and proline syntheses in endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 280, E75–E82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.M., Jr. Enzymes of arginine metabolism. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2743S–2747S; discussion 2765S–2767S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ming, X.F. Arginase: The emerging therapeutic target for vascular oxidative stress and inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Xia, N.; Li, H. Roles of Vascular Oxidative Stress and Nitric Oxide in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 713–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katusic, Z.S. Mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction induced by aging: Role of arginase I. Circ. Res. 2007, 101, 640–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, W.; Johnson, F.K.; Johnson, R.A. Arginase: A critical regulator of nitric oxide synthesis and vascular function. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2007, 34, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhoutte, P.M. Arginine and arginase: Endothelial NO synthase double crossed? Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 866–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernow, J.; Jung, C. Arginase as a potential target in the treatment of cardiovascular disease: Reversal of arginine steal? Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 98, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Vanhoutte, P.M.; Leung, S.W. Vascular nitric oxide: Beyond eNOS. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 129, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, R.; Blankenberg, S.; Lubos, E.; Lackner, K.J.; Rupprecht, H.J.; Espinola-Klein, C.; Jachmann, N.; Post, F.; Peetz, D.; Bickel, C.; et al. Asymmetric dimethylarginine and the risk of cardiovascular events and death in patients with coronary artery disease: Results from the AtheroGene Study. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, e53–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiber, A.; Xia, N.; Steven, S.; Oelze, M.; Hanf, A.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Münzel, T.; Li, H. New Therapeutic Implications of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase (eNOS) Function/Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, E.; Wenzel, P.; Münzel, T.; Daiber, A. Mitochondrial redox signaling: Interaction of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species with other sources of oxidative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasch, J.P.; Schmidt, P.M.; Nedvetsky, P.I.; Nedvetskaya, T.Y.; HS, S.A.; Meurer, S.; Deile, M.; Taye, A.; Knorr, A.; Lapp, H.; et al. Targeting the heme-oxidized nitric oxide receptor for selective vasodilatation of diseased blood vessels. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 2552–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, B.G.; Hu, X.; Brailey, J.L.; Berry, R.E.; Walker, F.A.; Montfort, W.R. Oxidation and loss of heme in soluble guanylyl cyclase from Manduca sexta. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 5813–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawa, M.; Okamura, T. Factors influencing the soluble guanylate cyclase heme redox state in blood vessels. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2022, 145, 107023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, M.T. Deconstructing endothelial dysfunction: Soluble guanylyl cyclase oxidation and the NO resistance syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 2330–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, M.W.; McMahon, T.J.; Stamler, J.S. S-nitrosylation in health and disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2003, 9, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.T.; Matsumoto, A.; Kim, S.O.; Marshall, H.E.; Stamler, J.S. Protein S-nitrosylation: Purview and parameters. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, N.; Baskaran, P.; Ma, X.; van den Akker, F.; Beuve, A. Desensitization of soluble guanylyl cyclase, the NO receptor, by S-nitrosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12312–12317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riego, J.A.; Broniowska, K.A.; Kettenhofen, N.J.; Hogg, N. Activation and inhibition of soluble guanylyl cyclase by S-nitrosocysteine: Involvement of amino acid transport system L. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 47, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, N.; Kim, D.D.; Fioramonti, X.; Iwahashi, T.; Durán, W.N.; Beuve, A. Nitroglycerin-induced S-nitrosylation and desensitization of soluble guanylyl cyclase contribute to nitrate tolerance. Circ. Res. 2008, 103, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Daiber, A.; Gori, T. Nitrate therapy: New aspects concerning molecular action and tolerance. Circulation 2011, 123, 2132–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galler, K.M.; Weber, M.; Korkmaz, Y.; Widbiller, M.; Feuerer, M. Inflammatory Response Mechanisms of the Dentine-Pulp Complex and the Periapical Tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kása, A.; Csortos, C.; Verin, A.D. Cytoskeletal mechanisms regulating vascular endothelial barrier function in response to acute lung injury. Tissue Barriers 2015, 3, e974448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolmatova, E.V.; Wang, K.; Mandavilli, R.; Griendling, K.K. The effects of sepsis on endothelium and clinical implications. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M.; Farges, J.C.; Lacerda-Pinheiro, S.; Six, N.; Jegat, N.; Decup, F.; Septier, D.; Carrouel, F.; Durand, S.; Chaussain-Miller, C.; et al. Inflammatory and immunological aspects of dental pulp repair. Pharmacol. Res. 2008, 58, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmaz, Y.; Lang, H.; Beikler, T.; Cho, B.; Behrends, S.; Bloch, W.; Addicks, K.; Raab, W.H. Irreversible inflammation is associated with decreased levels of the α1-, β1-, and α2-subunits of sGC in human odontoblasts. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farges, J.C.; Alliot-Licht, B.; Baudouin, C.; Msika, P.; Bleicher, F.; Carrouel, F. Odontoblast control of dental pulp inflammation triggered by cariogenic bacteria. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffre, J.; Hellman, J.; Ince, C.; Ait-Oufella, H. Endothelial Responses in Sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, C.L.; Falkler, W.A., Jr.; Siegel, M.A. A study of T and B cells in pulpal pathosis. J. Endod. 1989, 15, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, T.; Kobayashi, I.; Okamura, K.; Sakai, H. Immunohistochemical study on the immunocompetent cells of the pulp in human non-carious and carious teeth. Arch. Oral Biol. 1995, 40, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Abbott, P.V. An overview of the dental pulp: Its functions and responses to injury. Aust. Dent. J. 2007, 52, S4–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Karim, I.A.; Cooper, P.R.; About, I.; Tomson, P.L.; Lundy, F.T.; Duncan, H.F. Deciphering Reparative Processes in the Inflamed Dental Pulp. Front. Dent. Med. 2021, 2, 651219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craige, S.M.; Kant, S.; Keaney, J.F., Jr. Reactive oxygen species in endothelial function-from disease to adaptation. Circ. J. 2015, 79, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative stress: A concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Mailloux, R.J.; Jakob, U. Fundamentals of redox regulation in biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 701–719, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 758. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-024-00754-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, E.; Jansen, T.; Wenzel, P.; Daiber, A.; Münzel, T. Nitric oxide, tetrahydrobiopterin, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction in hypertension. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamler, J.S. Redox signaling: Nitrosylation and related target interactions of nitric oxide. Cell 1994, 78, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawanishi, H.N.; Kawashima, N.; Suzuki, N.; Suda, H.; Takagi, M. Effects of an inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibitor on experimentally induced rat pulpitis. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2004, 112, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawashima, N.; Nakano-Kawanishi, H.; Suzuki, N.; Takagi, M.; Suda, H. Effect of NOS inhibitor on cytokine and COX2 expression in rat pulpitis. J. Dent. Res. 2005, 84, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, R.; Cassina, A.; Hodara, R.; Quijano, C.; Castro, L. Peroxynitrite reactions and formation in mitochondria. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijhoff, J.; Winyard, P.G.; Zarkovic, N.; Davies, S.S.; Stocker, R.; Cheng, D.; Knight, A.R.; Taylor, E.L.; Oettrich, J.; Ruskovska, T.; et al. Clinical Relevance of Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 1144–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiber, A.; Hahad, O.; Andreadou, I.; Steven, S.; Daub, S.; Münzel, T. Redox-related biomarkers in human cardiovascular disease–classical footprints and beyond. Redox Biol. 2021, 42, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, J.S.; Ye, Y.Z.; Anderson, P.G.; Chen, J.; Accavitti, M.A.; Tarpey, M.M.; White, C.R. Extensive nitration of protein tyrosines in human atherosclerosis detected by immunohistochemistry. Biol. Chem. Hoppe Seyler 1994, 375, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beal, M.F.; Ferrante, R.J.; Browne, S.E.; Matthews, R.T.; Kowall, N.W.; Brown, R.H., Jr. Increased 3-nitrotyrosine in both sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 1997, 42, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, M.H.; Leist, M.; Ullrich, V. Selective nitration of prostacyclin synthase and defective vasorelaxation in atherosclerotic bovine coronary arteries. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 154, 1359–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassburger, M.; Bloch, W.; Sulyok, S.; Schüller, J.; Keist, A.F.; Schmidt, A.; Wenk, J.; Peters, T.; Wlaschek, M.; Lenart, J.; et al. Heterozygous deficiency of manganese superoxide dismutase results in severe lipid peroxidation and spontaneous apoptosis in murine myocardium in vivo. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005, 38, 1458–1470, Erratum in Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 40, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Harrison, D.G. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: The role of oxidant stress. Circ. Res. 2000, 87, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.J.; Kikuchi, D.S.; Hernandes, M.S.; Xu, Q.; Griendling, K.K. Reactive Oxygen Species in Metabolic and Inflammatory Signaling. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.L. eNOS, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 20, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hühmer, A.F.; Gerber, N.C.; de Montellano, P.R.; Schöneich, C. Peroxynitrite reduction of calmodulin stimulation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1996, 9, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zippel, N.; Loot, A.E.; Stingl, H.; Randriamboavonjy, V.; Fleming, I.; Fisslthaler, B. Endothelial AMP-Activated Kinase α1 Phosphorylates eNOS on Thr495 and Decreases Endothelial NO Formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Dörscher-Kim, J. Hemodynamic regulation of the dental pulp in a low compliance environment. J. Endod. 1989, 15, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Gao, X.; Liu, Y.; Mao, W.; Chen, S.L. Resveratrol ameliorates low shear stress-induced oxidative stress by suppressing ERK/eNOS-Thr495 in endothelial cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 10, 1964–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Qu, X.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Chao, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wu, W.; Chen, S.L. Modulation of low shear stress-induced eNOS multi-site phosphorylation and nitric oxide production via protein kinase and ERK1/2 signaling. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S. Ivabradine Prevents Low Shear Stress Induced Endothelial Inflammation and Oxidative Stress via mTOR/eNOS Pathway. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.; Ye, P.; Zhu, L.; Kong, X.; Qu, X.; Zhang, J.; Luo, J.; Yang, H.; Chen, S. Low shear stress induces endothelial reactive oxygen species via the AT1R/eNOS/NO pathway. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 1384–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitzer, T.; Brockhoff, C.; Mayer, B.; Warnholtz, A.; Mollnau, H.; Henne, S.; Meinertz, T.; Münzel, T. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in chronic smokers: Evidence for a dysfunctional nitric oxide synthase. Circ. Res. 2000, 86, E36–E41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milstien, S.; Katusic, Z. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin by peroxynitrite: Implications for vascular endothelial function. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 263, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharina, I.G.; Martin, E. The Role of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species in the Expression and Splicing of Nitric Oxide Receptor. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 26, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Lauer, N.; Mülsch, A.; Kojda, G. The effect of peroxynitrite on the catalytic activity of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001, 31, 1360–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawa, M.; Shimosato, T.; Iwasaki, H.; Imamura, T.; Okamura, T. Effects of peroxynitrite on relaxation through the NO/sGC/cGMP pathway in isolated rat iliac arteries. J. Vasc. Res. 2014, 51, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melichar, V.O.; Behr-Roussel, D.; Zabel, U.; Uttenthal, L.O.; Rodrigo, J.; Rupin, A.; Verbeuren, T.J.; Kumar, H.S.A.; Schmidt, H.H. Reduced cGMP signaling associated with neointimal proliferation and vascular dysfunction in late-stage atherosclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 16671–16676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, Y.; Bloch, W.; Steinritz, D.; Baumann, M.A.; Addicks, K.; Schneider, K.; Raab, W.H. Bradykinin mediates phosphorylation of eNOS in odontoblasts. J. Dent. Res. 2006, 85, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanese, I.; Khan, K.; Barratt, B.; Al-Kindi, H.; Schwertani, A. Atherosclerotic Calcification: Wnt Is the Hint. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e007356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawa, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Shibata, K.I.; Suzuki, M.; Mukaida, A. Vascular endothelium of human dental pulp expresses diverse adhesion molecules for leukocyte emigration. Tissue Cell 1998, 30, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.J. Vitality of the dentin-pulp complex in health and disease: Growth factors as key mediators. J. Dent. Educ. 2003, 67, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, H.F. Present status and future directions-Vital pulp treatment and pulp preservation strategies. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M.; Kulkarni, A.B.; Young, M.; Boskey, A. Dentin: Structure, composition and mineralization. Front. Biosci. 2011, 3, 711–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, A. Dentin matrix proteins: Composition and possible functions in calcification. Anat. Rec. 1989, 224, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.J.; Cassidy, N.; Perry, H.; Bègue-Kirn, C.; Ruch, J.V.; Lesot, H. Reactionary dentinogenesis. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1995, 39, 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, P.E.; About, I.; Lumley, P.J.; Smith, G.; Franquin, J.C.; Smith, A.J. Postoperative pulpal and repair responses. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2000, 131, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, V.C.M.; Sharpe, P.T. Regulation of Reactionary Dentine Formation. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.G.; Smith, A.J.; Shelton, R.M.; Cooper, P.R. Recruitment of dental pulp cells by dentine and pulp extracellular matrix components. Exp. Cell Res. 2012, 318, 2397–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yianni, V.; Sharpe, P.T. Perivascular-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vongsavan, N.; Matthews, B. The vascularity of dental pulp in cats. J. Dent. Res. 1992, 71, 1913–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.W. Pulpal blood flow: Use of radio-labelled microspheres. Int. Endod. J. 1993, 26, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Kishi, Y.; Kim, S. A scanning electron microscope study of the blood vessels of dog pulp using corrosion resin casts. J. Endod. 1982, 8, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, Y.; Shimozato, N.; Takahashi, K. Vascular architecture of cat pulp using corrosive resin cast under scanning electron, microscopy. J. Endod. 1989, 15, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpron, R.E.; Avery, J.K.; Lee, S.D. Ultrastructure of capillaries in the odontoblastic layer. J. Dent. Res. 1973, 52, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabinejad, M.; Peters, D.L.; Peckham, N.; Rentchler, L.R.; Richardson, J. Electron microscopic changes in human pulps after intraligamental injection. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1993, 76, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Daiber, A.; Gori, T. More answers to the still unresolved question of nitrate tolerance. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 2666–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Steven, S.; Daiber, A. Organic nitrates: Update on mechanisms underlying vasodilation, tolerance and endothelial dysfunction. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 63, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushio-Fukai, M.; Ash, D.; Nagarkoti, S.; Belin de Chantemèle, E.J.; Fulton, D.J.R.; Fukai, T. Interplay Between Reactive Oxygen/Reactive Nitrogen Species and Metabolism in Vascular Biology and Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 34, 1319–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabó, C.; Ischiropoulos, H.; Radi, R. Peroxynitrite: Biochemistry, pathophysiology and development of therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 662–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacher, P.; Beckman, J.S.; Liaudet, L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 315–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, E.; Tsilimingas, N.; Rinze, R.; Reiter, B.; Wendt, M.; Oelze, M.; Woelken-Weckmüller, S.; Walter, U.; Reichenspurner, H.; Meinertz, T.; et al. Functional and biochemical analysis of endothelial (dys)function and NO/cGMP signaling in human blood vessels with and without nitroglycerin pretreatment. Circulation 2002, 105, 1170–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulce, R.A.; Schulman, I.H.; Hare, J.M. S-glutathionylation: A redox-sensitive switch participating in nitroso-redox balance. Circ. Res. 2011, 108, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmesser, U.; Drexler, H. The clinical significance of endothelial dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2005, 20, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münzel, T.; Daiber, A. Vascular Redox Signaling, Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Uncoupling, and Endothelial Dysfunction in the Setting of Transportation Noise Exposure or Chronic Treatment with Organic Nitrates. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2023, 38, 1001–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Gori, T.; Bruno, R.M.; Taddei, S. Is oxidative stress a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease? Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 2741–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunnington, C.; Van Assche, T.; Shirodaria, C.; Kylintireas, I.; Lindsay, A.C.; Lee, J.M.; Antoniades, C.; Margaritis, M.; Lee, R.; Cerrato, R.; et al. Systemic and vascular oxidation limits the efficacy of oral tetrahydrobiopterin treatment in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 2012, 125, 1356–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, E.; Channon, K.M. The role of tetrahydrobiopterin in inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Thromb. Haemost. 2012, 108, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, E.J.; Kass, D.A. Cyclic GMP signaling in cardiovascular pathophysiology and therapeutics. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 122, 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandner, P.; Follmann, M.; Becker-Pelster, E.; Hahn, M.G.; Meier, C.; Freitas, C.; Roessig, L.; Stasch, J.P. Soluble GC stimulators and activators: Past, present and future. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 181, 4130–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharina, I.; Martin, E. Cellular Factors That Shape the Activity or Function of Nitric Oxide-Stimulated Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase. Cells 2023, 12, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friebe, A.; Englert, N. NO-sensitive guanylyl cyclase in the lung. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 2328–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englert, N.; Burkard, P.; Aue, A.; Rosenwald, A.; Nieswandt, B.; Friebe, A. Anti-Fibrotic and Anti-Inflammatory Role of NO-Sensitive Guanylyl Cyclase in Murine Lung. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follmann, M.; Griebenow, N.; Hahn, M.G.; Hartung, I.; Mais, F.J.; Mittendorf, J.; Schäfer, M.; Schirok, H.; Stasch, J.P.; Stoll, F.; et al. The chemistry and biology of soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators and activators. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9442–9462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasch, J.P.; Becker, E.M.; Alonso-Alija, C.; Apeler, H.; Dembowsky, K.; Feurer, A.; Gerzer, R.; Minuth, T.; Perzborn, E.; Pleiss, U.; et al. NO-independent regulatory site on soluble guanylate cyclase. Nature 2001, 410, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakalopoulos, A.; Wunder, F.; Hartung, I.V.; Redlich, G.; Jautelat, R.; Buchgraber, P.; Hassfeld, J.; Gromov, A.V.; Lindner, N.; Bierer, D.; et al. New Generation of sGC Stimulators: Discovery of Imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine Carboxamide BAY 1165747 (BAY-747), a Long-Acting Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulator for the Treatment of Resistant Hypertension. J Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 7280–7303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benza, R.L.; Grünig, E.; Sandner, P.; Stasch, J.P.; Simonneau, G. The nitric oxide-soluble guanylate cyclase-cGMP pathway in pulmonary hypertension: From PDE5 to soluble guanylate cyclase. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2024, 33, 230183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omori, K.; Kotera, J. Overview of PDEs and their regulation. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurice, D.H.; Ke, H.; Ahmad, F.; Wang, Y.; Chung, J.; Manganiello, V.C. Advances in targeting cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 290–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samidurai, A.; Xi, L.; Das, A.; Kukreja, R.C. Beyond Erectile Dysfunction: cGMP-Specific Phosphodiesterase 5 Inhibitors for Other Clinical Disorders. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2023, 63, 585–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kass, D.A.; Champion, H.C.; Beavo, J.A. Phosphodiesterase type 5: Expanding roles in cardiovascular regulation. Circ. Res. 2007, 101, 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lteif, C.; Ataya, A.; Duarte, J.D. Therapeutic Challenges and Emerging Treatment Targets for Pulmonary Hypertension in Left Heart Disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiè, N.; Humbert, M.; Vachiery, J.L.; Gibbs, S.; Lang, I.; Torbicki, A.; Simonneau, G.; Peacock, A.; Vonk Noordegraaf, A.; Beghetti, M.; et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 67–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Korkmaz, Y.; Kollmar, T.; Schultheis, J.F.; Cores Ziskoven, P.; Müller-Heupt, L.K.; Deschner, J. NO-cGMP Signaling in Endothelial Function of the Healthy and Inflamed Dental Pulp. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010057

Korkmaz Y, Kollmar T, Schultheis JF, Cores Ziskoven P, Müller-Heupt LK, Deschner J. NO-cGMP Signaling in Endothelial Function of the Healthy and Inflamed Dental Pulp. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorkmaz, Yüksel, Tobias Kollmar, Judith F. Schultheis, Pablo Cores Ziskoven, Lena K. Müller-Heupt, and James Deschner. 2026. "NO-cGMP Signaling in Endothelial Function of the Healthy and Inflamed Dental Pulp" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010057

APA StyleKorkmaz, Y., Kollmar, T., Schultheis, J. F., Cores Ziskoven, P., Müller-Heupt, L. K., & Deschner, J. (2026). NO-cGMP Signaling in Endothelial Function of the Healthy and Inflamed Dental Pulp. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010057