Discovery of New 7-Propanamide Benzoxaborole as Potent Anti-SKOV3 Agent via 3D-QSAR Models

Abstract

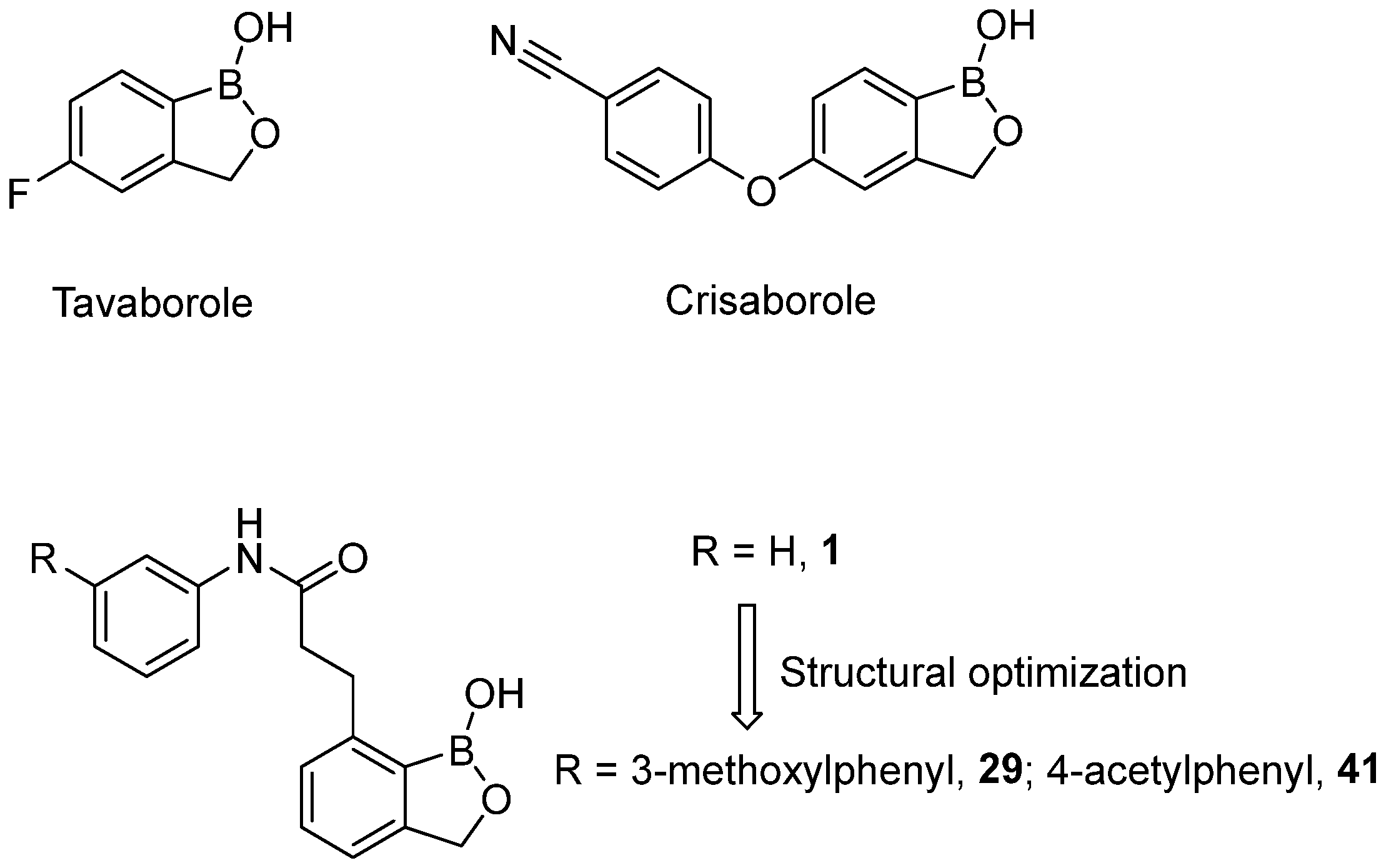

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. 3D-QSAR Study

2.1.1. Acquisition of Conformations

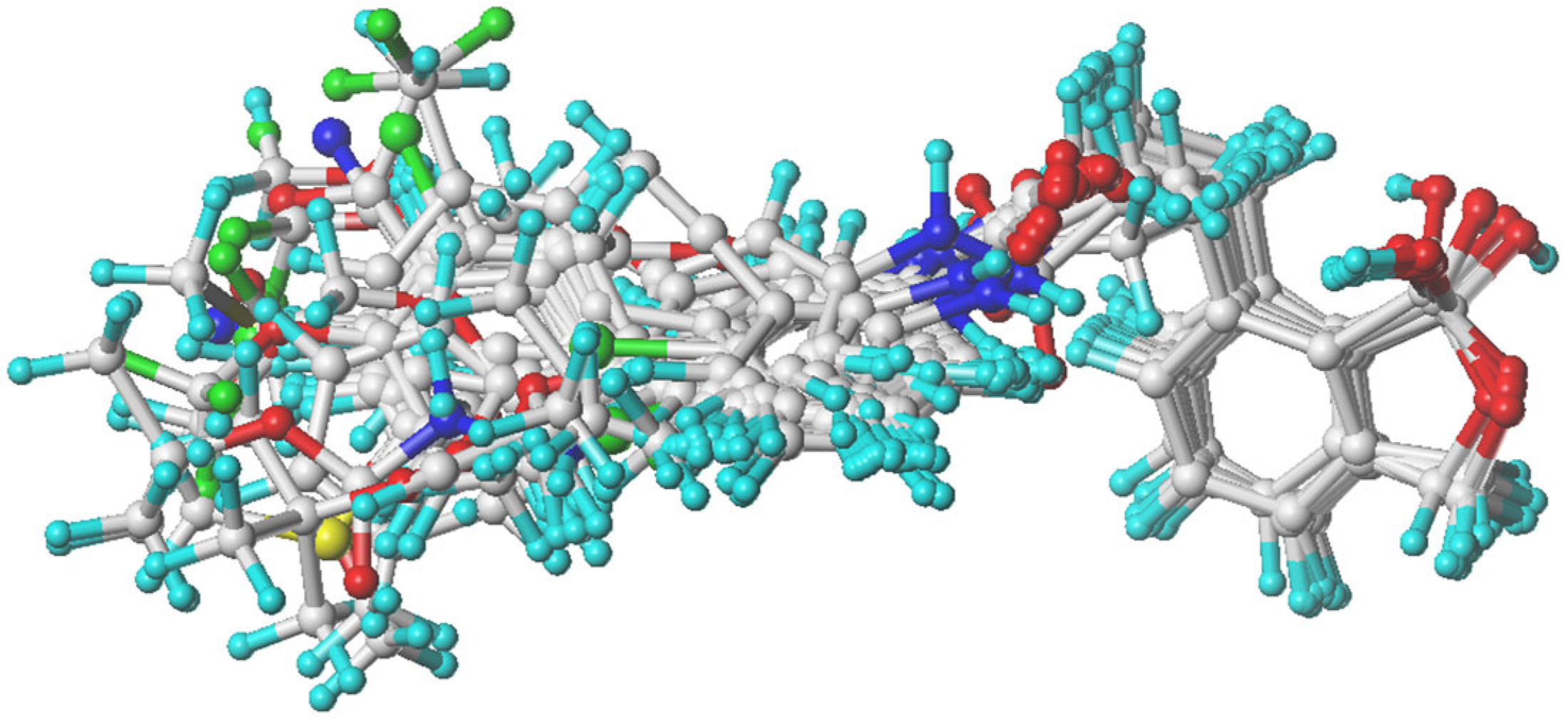

2.1.2. Molecular Alignment

2.1.3. 3D-QSAR Statistics

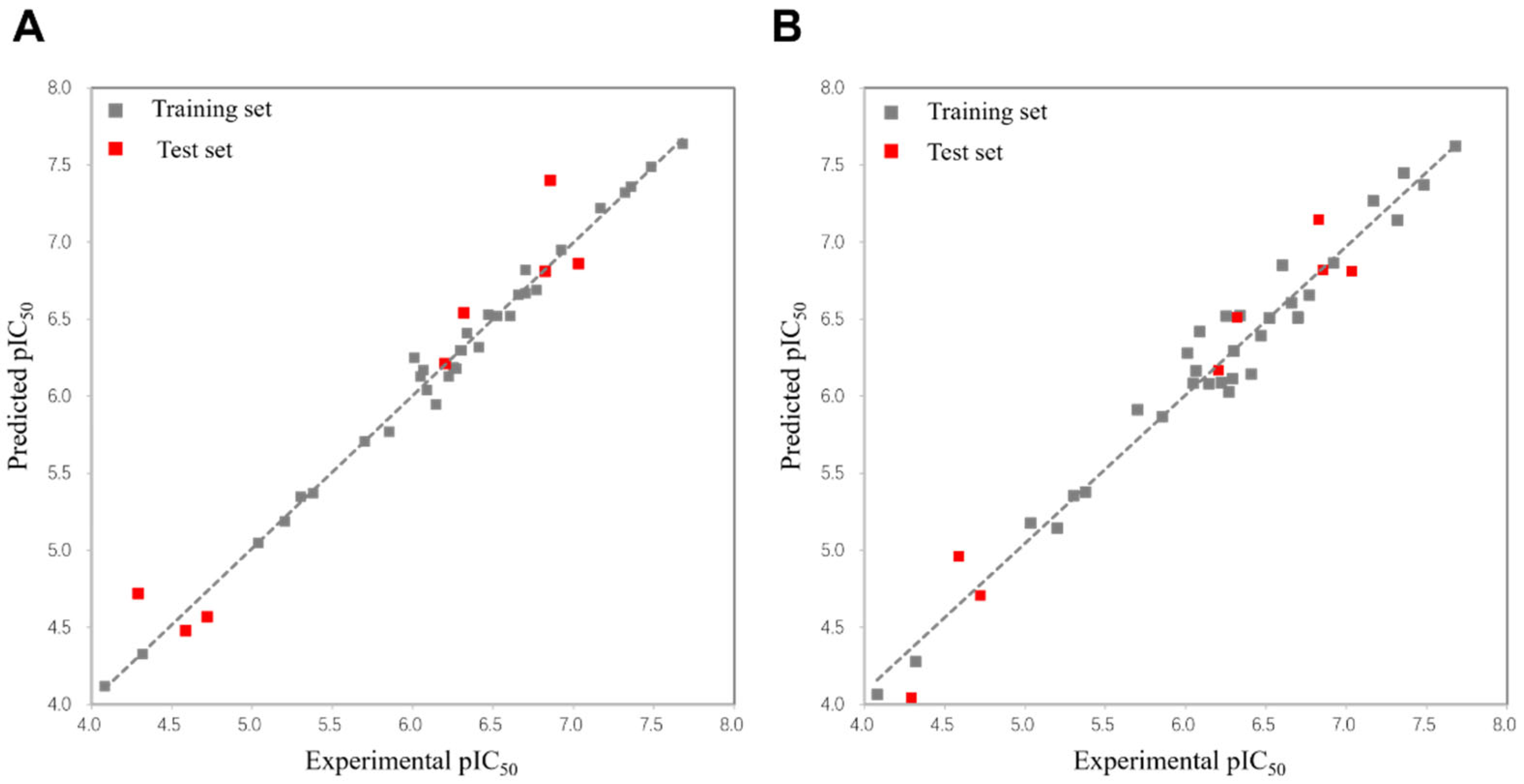

2.1.4. Validation of the 3D-QSAR Models

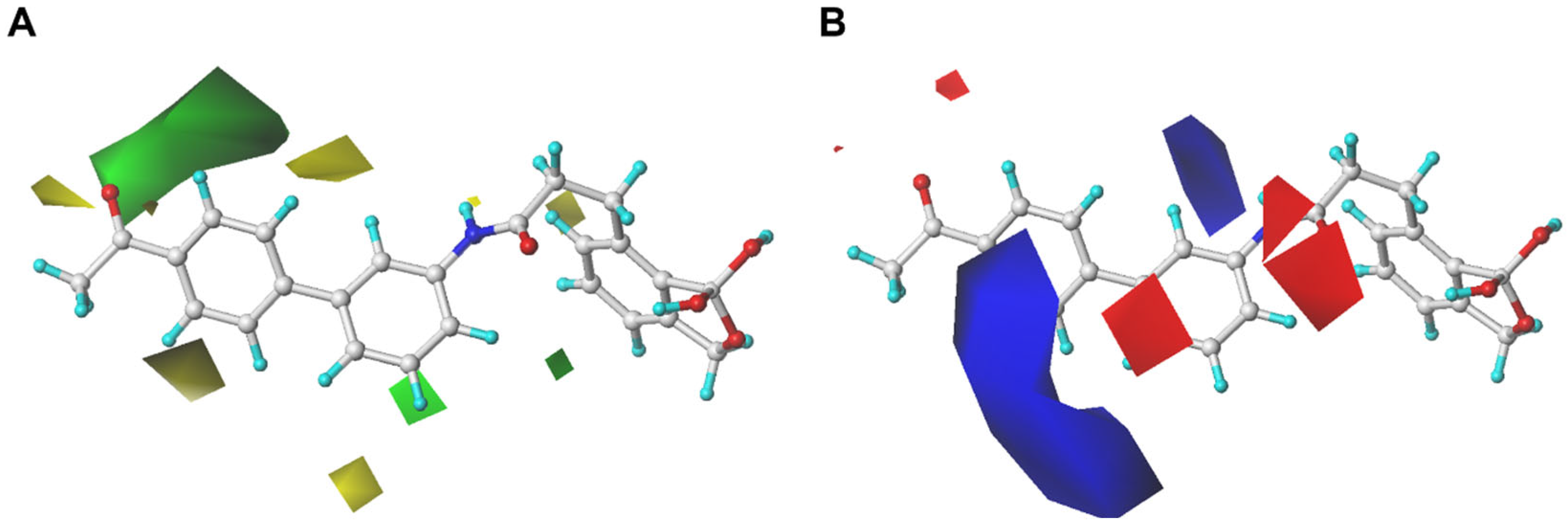

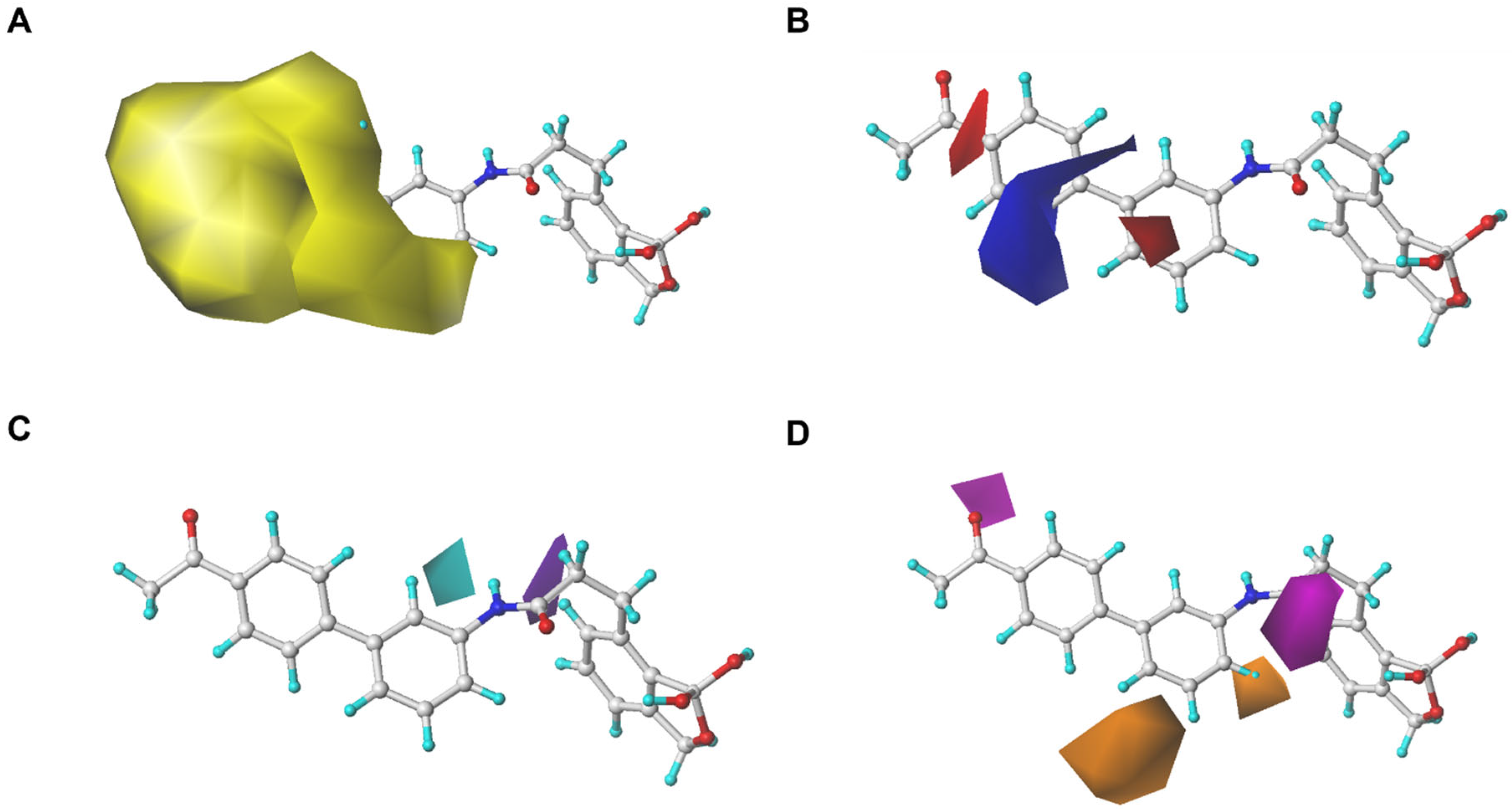

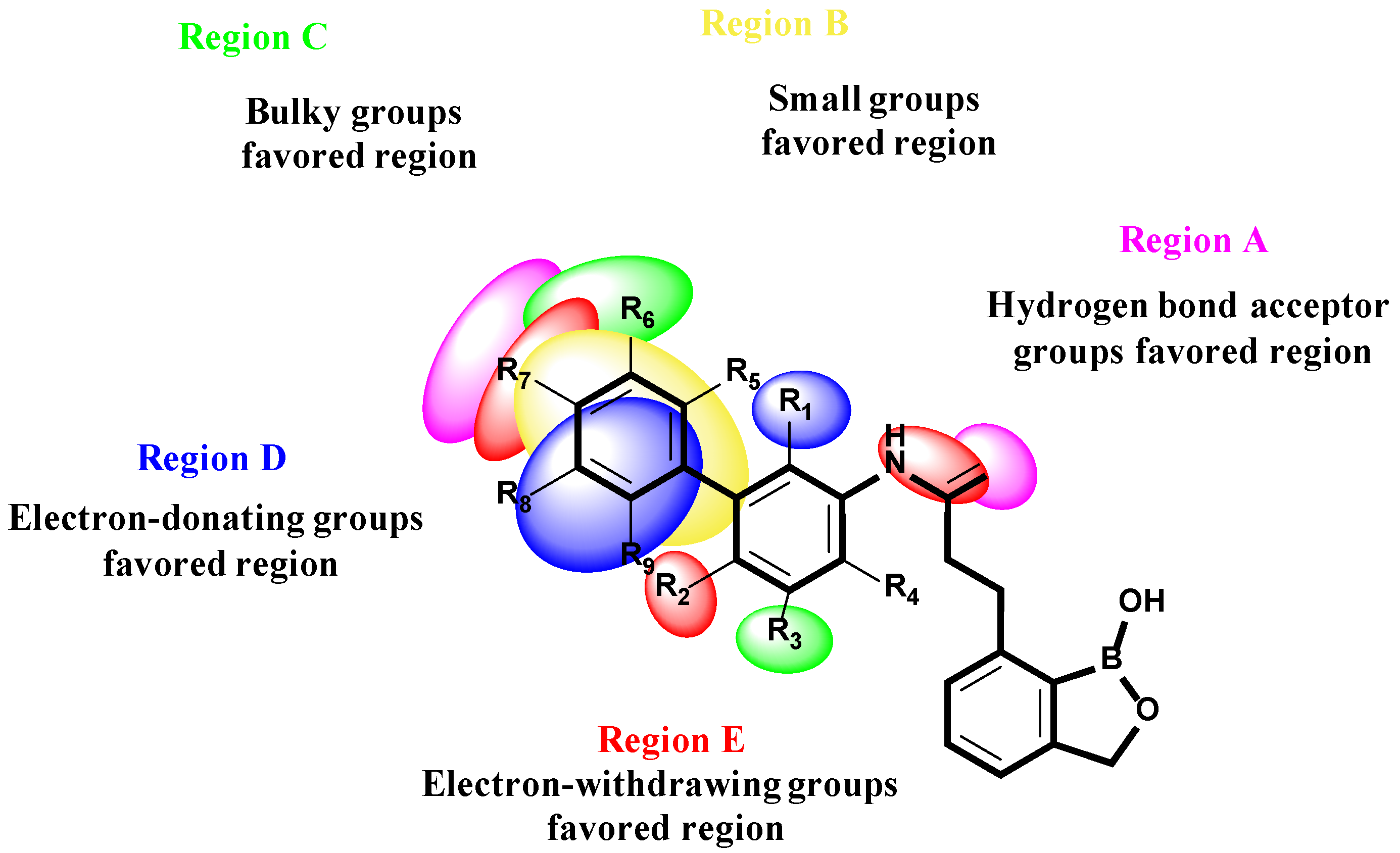

2.1.5. Analysis of Contour Maps

2.1.6. SAR Summary

2.2. Design of New Anti-SKOV3 Agent

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. 3D-QSAR Construction

3.1.1. 3D-QSAR Modeling Dataset

3.1.2. Generation of Conformational Ensembles

3.1.3. Molecular Alignment

3.1.4. CoMFA and CoMSIA Model Building

3.1.5. 3D-QSAR Model Validation

3.2. Experimental Validation

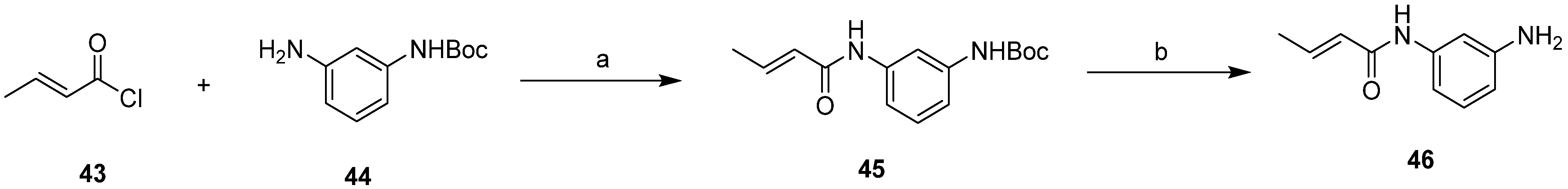

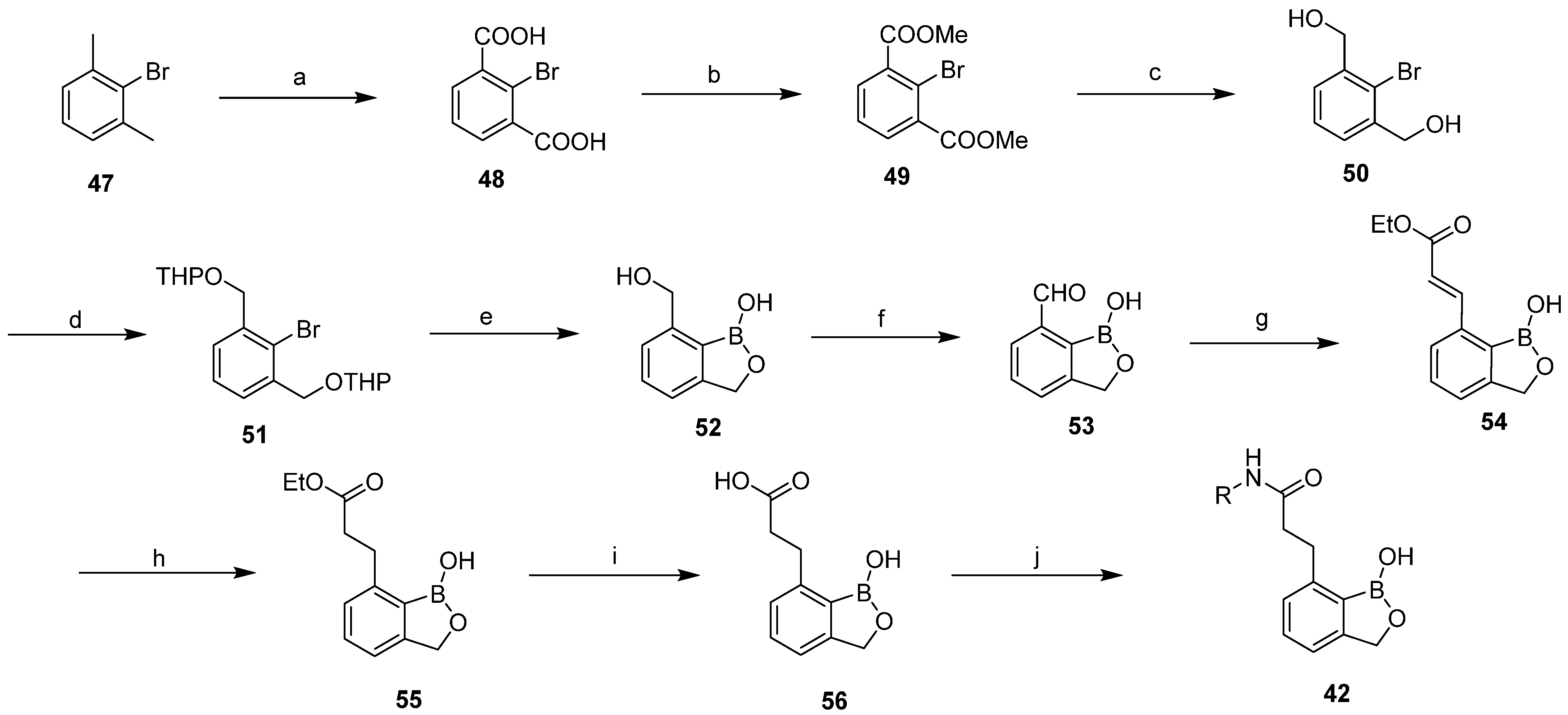

3.2.1. Chemistry

3.2.2. Cell Culture

3.2.3. In Vitro Proliferation Assessment

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.; Hou, X.B.; Fang, H. Application of benzoxaboroles compounds in medicinal chemistry. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2019, 54, 1940–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, M.Y.; Lin, Y.N.; Zhou, H.C. The synthesis of benzoxaboroles and their applications in medicinal chemistry. Sci. China Chem. 2013, 56, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Zhao, Y.; Meng, Q.; Xie, D.; Nare, B.; Chen, D.; Bacchi, C.J.; Yarlett, N.; Zhang, Y.-K.; Hernandez, V.; et al. Discovery of novel benzoxaborole-based potent antitrypanosomal agents. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Meng, Q.; Gao, G.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Nare, B.; Jacobs, R.; Rock, F.; Alley, M.R.K.; Plattner, J.J.; et al. Design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship of Trypanosoma brucei leucyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitors as antitrypanosomal agents. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Bowling, T.; Nare, B.; Jacobs, R.T.; Zhang, J.; Ding, D.; Liu, Y.; et al. Chalcone-benzoxaborole hybrid molecules as potent antitrypanosomal agents. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3553–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, F.; Qiao, Z.T.; Zhu, M.Y.; Zhou, H.C. Chalcone-benzoxaborole hybrids as novel anticancer agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 5797–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Hao, G.; Xin, W.; Yang, F.; Zhu, M.; Zhou, H. Design, Synthesis, and structure-activity relationship of 7-propanamide benzoxaboroles as potent anticancer agents. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 6765–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Virtucio, C.; Zemska, O.; Baltazar, G.; Zhou, Y.; Baia, D.; Jones-Iatauro, S.; Sexton, H.; Martin, S.; Dee, J.; et al. Treatment of skin inflammation with benzoxaborole phosphodiesterase inhibitors: Selectivity, cellular activity, and effect on cytokines associated with skin inflammation and skin architecture. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2016, 358, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, F.L.; Mao, W.; Yaremchuk, A.; Tukalo, M.; Crepin, T.; Zhou, H.C.; Zhang, Y.K.; Hernandez, V.; Akama, T.; Baker, S.J.; et al. An antifungal agent inhibits an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase by trapping tRNA in the editing site. Science 2007, 316, 1759–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Budhipramono, A.; Huang, J.; Fang, M.; Xie, S.; Kim, J.; Khivansara, V.; Dominski, Z.; Tong, L.; De Brabander, J.K.; et al. Anticancer benzoxaboroles block pre-mRNA processing by directly inhibiting CPSF3. Cell Chem. Biol. 2024, 31, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macalino, S.J.Y.; Gosu, V.; Hong, S.H.; Choi, S. Role of computer-aided drug design in modern drug discovery. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2015, 38, 1686–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Ma, Z.; Yu, X.; Chen, W.; Teng, P.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xia, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, W. 3D-QSAR-directed synthesis of halogenated coumarin-3-hydrazide derivatives: Unveiling their potential as SDHI antifungal agents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 11938–11948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Ji, X.; Gao, W.; Yu, Z.; Li, K.; Xiong, L.; Yang, N.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Fan, Z. 3D-QSAR-based molecular design to discover ultrahigh active N-phenylpyrazoles as insecticide candidates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 4258–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Thakur, S.; Manhas, D.; Reddy, C.N.; Eedara, A.; Guru, S.K.; Singh, A.; Bhardwaj, M.; Kambhampati, V.; Pandian, R.; et al. Discovery of 2-(4-Ureido-piperidin-1-yl)-4-morpholinothieno [3,2-D] pyrimidines as orally bioavailable phosphoinositide-3-kinase inhibitors with in vitro and in vivo antitumor efficacy in triple-negative breast cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 21282–21317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaver, D.J.; Cleary, B.; Nguyen, N.T.-E.; Priebbenow, D.L.; Lagiakos, H.R.; Sanchez, J.; Xue, L.; Huang, F.; Sun, Y.; Mujumdar, P.; et al. Discovery of benzoylsulfonohydrazides as potent inhibitors of the histone acetyltransferase KAT6A. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 7146–7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yan, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, L.; Yu, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Cheng, J. Structure-guided design of novel 5-HT2A partial agonists as psychedelic analogues with antidepressant effects. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 21683–21700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ma, L.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Lei, Z.-N.; Gupta, P.; Zhao, Y.-D.; Li, Z.-H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.-H.; Li, Y.-N.; et al. Discovery of 5-cyano-6-phenylpyrimidin derivatives containing an acylurea moiety as orally bioavailable reversal agents against P-glycoprotein-mediated mutidrug resistance. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5988–6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, P.; Dvorácskó, S.; Volesky, P.; Pointeau, O.; Rutland, N.; Maccioni, L.; Godlewski, G.; Jourdan, T.; Hassan, S.A.; Cinar, R.; et al. Leveraging peripheral CB1 antagonism in 1,4,5,6-tetrahydropyridazine-based amidine substituted sulfonyl analogs for treating metabolic disorders. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 21224–21248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Ding, D.; Feng, Y.; Xie, D.; Wu, P.; Guo, H.; Meng, Q.; Zhou, H. Convenient and versatile synthesis of formyl-substituted benzoxaboroles. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 8738–8744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastry, G.M.; Adzhigirey, M.; Day, T.; Annabhimoju, R.; Sherman, W. Protein and ligand preparation: Parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2013, 27, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelley, J.C.; Cholleti, A.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Timlin, M.R.; Uchimaya, M. Epik: A software program for pK a prediction and protonation state generation for drug-like molecules. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2007, 21, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, K.S.; Dalal, P.; Murphy, R.B.; Sherman, W.; Friesner, R.A.; Shelley, J.C. ConfGen: A conformational search method for efficient generation of bioactive conformers. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yan, W.; Wang, S.; Lu, M.; Yang, H.; Chai, X.; Shi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Q. Discovery of selective HDAC6 inhibitors based on a multi-layer virtual screening strategy. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 160, 107036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Yu, X.; Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Meng, F.; Zhao, Y.; Xiong, L.; Yang, N.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.-M. Synthesis, insecticidal evaluation, and 3D-QASR of novel anthranilic diamide derivatives containing N-arylpyrrole as potential ryanodine receptor activators. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 9319–9328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbraikh, A.; Tropsha, A. Beware of q2. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2002, 20, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. | R | pIC50 | CoMFA | CoMSIA | ||

| Exp. | Pred. | Res. | Pred. | Res. | ||

| Training Set | ||||||

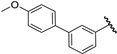

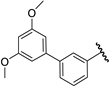

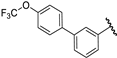

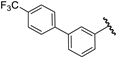

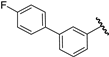

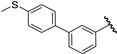

| 1 |  | 6.70 | 6.67 | −0.03 | 6.52 | −0.18 |

| 2 |  | 6.14 | 5.95 | −0.19 | 6.08 | −0.06 |

| 3 |  | 5.30 | 5.35 | 0.05 | 5.35 | 0.05 |

| 4 |  | 5.04 | 5.05 | 0.01 | 5.18 | 0.14 |

| 6 |  | 6.07 | 6.17 | 0.10 | 6.17 | 0.10 |

| 7 |  | 5.20 | 5.19 | −0.01 | 5.14 | −0.06 |

| 8 |  | 5.38 | 5.37 | −0.01 | 5.38 | 0.00 |

| 9 |  | 6.05 | 6.13 | 0.08 | 6.08 | 0.03 |

| 10 |  | 5.70 | 5.71 | 0.01 | 5.91 | 0.21 |

| 11 |  | 4.08 | 4.12 | 0.04 | 4.06 | −0.02 |

| 12 |  | 6.27 | 6.18 | −0.09 | 6.03 | −0.24 |

| 14 |  | 6.29 | 6.30 | 0.01 | 6.11 | −0.18 |

| 15 |  | 6.01 | 6.25 | 0.24 | 6.28 | 0.27 |

| 16 |  | 6.70 | 6.82 | 0.12 | 6.51 | −0.19 |

| 17 |  | 6.09 | 6.04 | −0.05 | 6.42 | 0.33 |

| 18 |  | 6.22 | 6.13 | −0.09 | 6.09 | −0.13 |

| 20 |  | 6.77 | 6.69 | −0.08 | 6.66 | −0.11 |

| 21 |  | 5.85 | 5.77 | −0.08 | 5.86 | 0.01 |

| 23 |  | 6.60 | 6.52 | −0.08 | 6.85 | 0.25 |

| 24 |  | 4.32 | 4.33 | 0.01 | 4.28 | −0.04 |

| 27 |  | 6.52 | 6.52 | 0.00 | 6.51 | −0.01 |

| 28 |  | 6.66 | 6.66 | 0.00 | 6.61 | −0.05 |

| 29 |  | 7.48 | 7.49 | 0.01 | 7.37 | −0.11 |

| 30 |  | 7.32 | 7.32 | 0.00 | 7.14 | −0.18 |

| 31 |  | 7.36 | 7.36 | 0.00 | 7.45 | 0.09 |

| 32 |  | 6.34 | 6.41 | 0.07 | 6.52 | 0.18 |

| 33 |  | 6.25 | 6.19 | −0.06 | 6.52 | 0.27 |

| 36 |  | 6.41 | 6.32 | −0.09 | 6.14 | −0.27 |

| 37 |  | 6.30 | 6.30 | 0.00 | 6.29 | −0.01 |

| 38 |  | 6.92 | 6.95 | 0.03 | 6.86 | −0.06 |

| 39 |  | 6.47 | 6.53 | 0.06 | 6.39 | −0.08 |

| 40 |  | 7.17 | 7.22 | 0.05 | 7.27 | 0.10 |

| 41 |  | 7.68 | 7.64 | −0.04 | 7.62 | −0.06 |

| Test Set | ||||||

| 5 |  | 4.29 | 4.72 | 0.43 | 4.04 | −0.25 |

| 13 |  | 6.20 | 6.21 | 0.01 | 6.17 | −0.03 |

| 19 |  | 4.72 | 4.57 | −0.15 | 4.71 | −0.01 |

| 22 |  | 4.58 | 4.48 | −0.10 | 4.96 | 0.38 |

| 25 |  | 6.32 | 6.54 | 0.22 | 6.51 | 0.19 |

| 26 |  | 7.03 | 6.86 | −0.17 | 6.81 | −0.22 |

| 34 |  | 6.82 | 6.81 | −0.01 | 7.15 | 0.32 |

| 35 |  | 6.85 | 7.40 | 0.55 | 6.82 | −0.03 |

| Statistical Parameters | CoMFA | CoMSIA |

|---|---|---|

| q2 a | 0.626 | 0.605 |

| N b | 8 | 6 |

| r2 c | 0.991 | 0.964 |

| SEE d | 0.090 | 0.173 |

| F e | 327.630 | 116.389 |

| r2pred f | 0.941 | 0.961 |

| r2m g | 0.796 | 0.919 |

| SDEPext h | 0.260 | 0.308 |

| Fraction of field contributions | ||

| S i | 0.729 | 0.163 |

| E j | 0.271 | 0.228 |

| D k | - | 0.222 |

| A l | - | 0.387 |

| Comp. | Structure | Pred. (CoMFA) | Pred. (CoMSIA) | Exp. (pIC50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

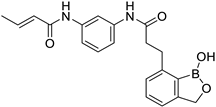

| 42 |  | 7.19 | 7.34 | 7.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ji, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, Y. Discovery of New 7-Propanamide Benzoxaborole as Potent Anti-SKOV3 Agent via 3D-QSAR Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010472

Ji L, Zhang J, Zhou H, Zhao Y. Discovery of New 7-Propanamide Benzoxaborole as Potent Anti-SKOV3 Agent via 3D-QSAR Models. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010472

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Liyang, Jiong Zhang, Huchen Zhou, and Yaxue Zhao. 2026. "Discovery of New 7-Propanamide Benzoxaborole as Potent Anti-SKOV3 Agent via 3D-QSAR Models" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010472

APA StyleJi, L., Zhang, J., Zhou, H., & Zhao, Y. (2026). Discovery of New 7-Propanamide Benzoxaborole as Potent Anti-SKOV3 Agent via 3D-QSAR Models. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010472