N-Stearidonoylethanolamine Restores CA1 Synaptic Integrity and Reduces Astrocytic Reactivity After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

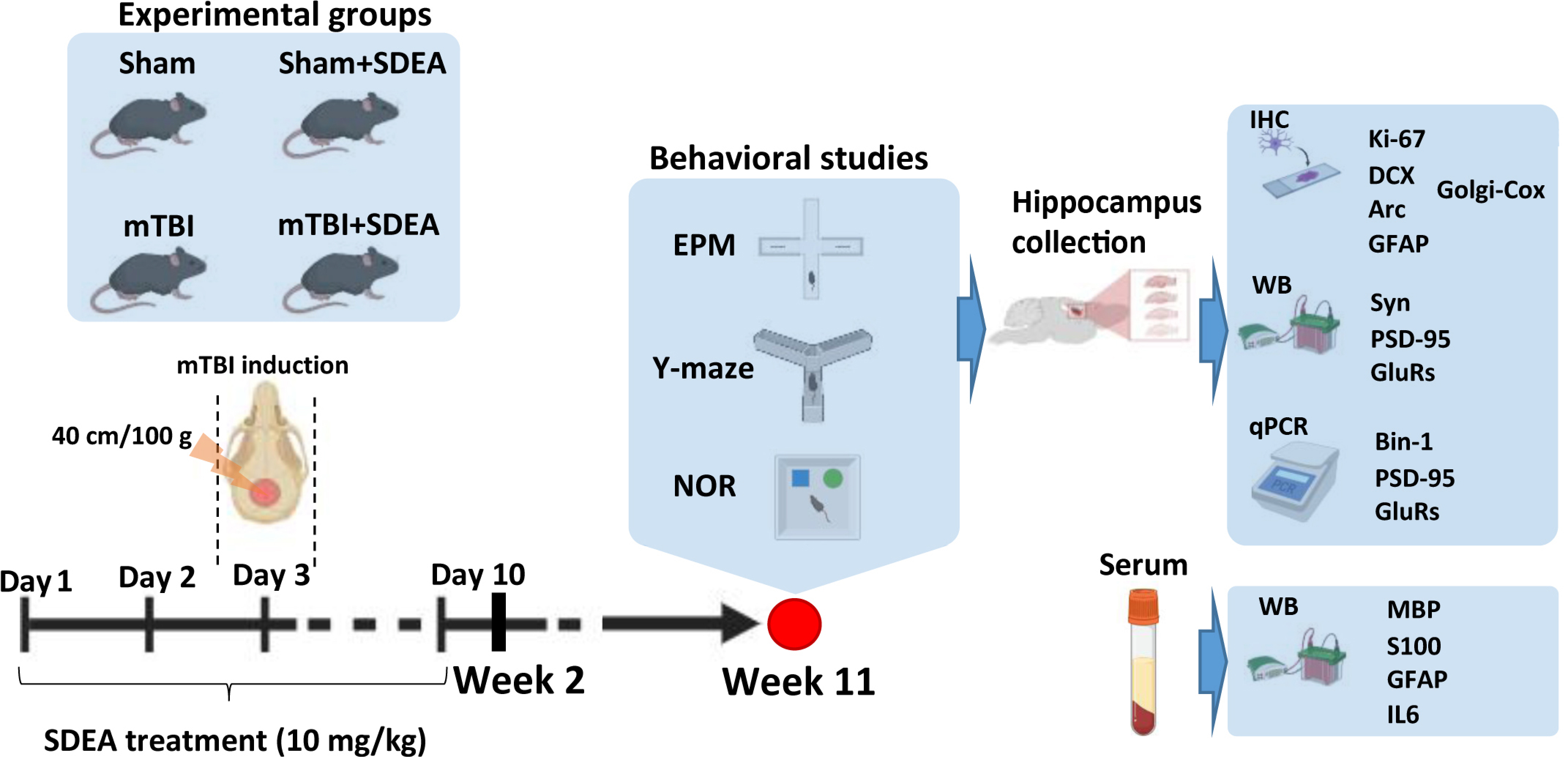

2. Results

2.1. Behavioral Outcomes: Cognitive and Emotional Consequences of mTBI and Treatment

2.1.1. Elevated Plus Maze

2.1.2. Y-Maze

2.1.3. Novel Object Recognition

2.2. Effect of mTBI and SDEA Treatment on Hippocampal Neurogenesis

2.3. Effect of mTBI and SDEA Treatment on Arc Production

2.4. Spine Remodeling After mTBI and SDEA Treatment

2.4.1. CA1 Apical Dendrites

2.4.2. CA1 Basal Dendrites

2.4.3. Dentate Gyrus Granule Cells

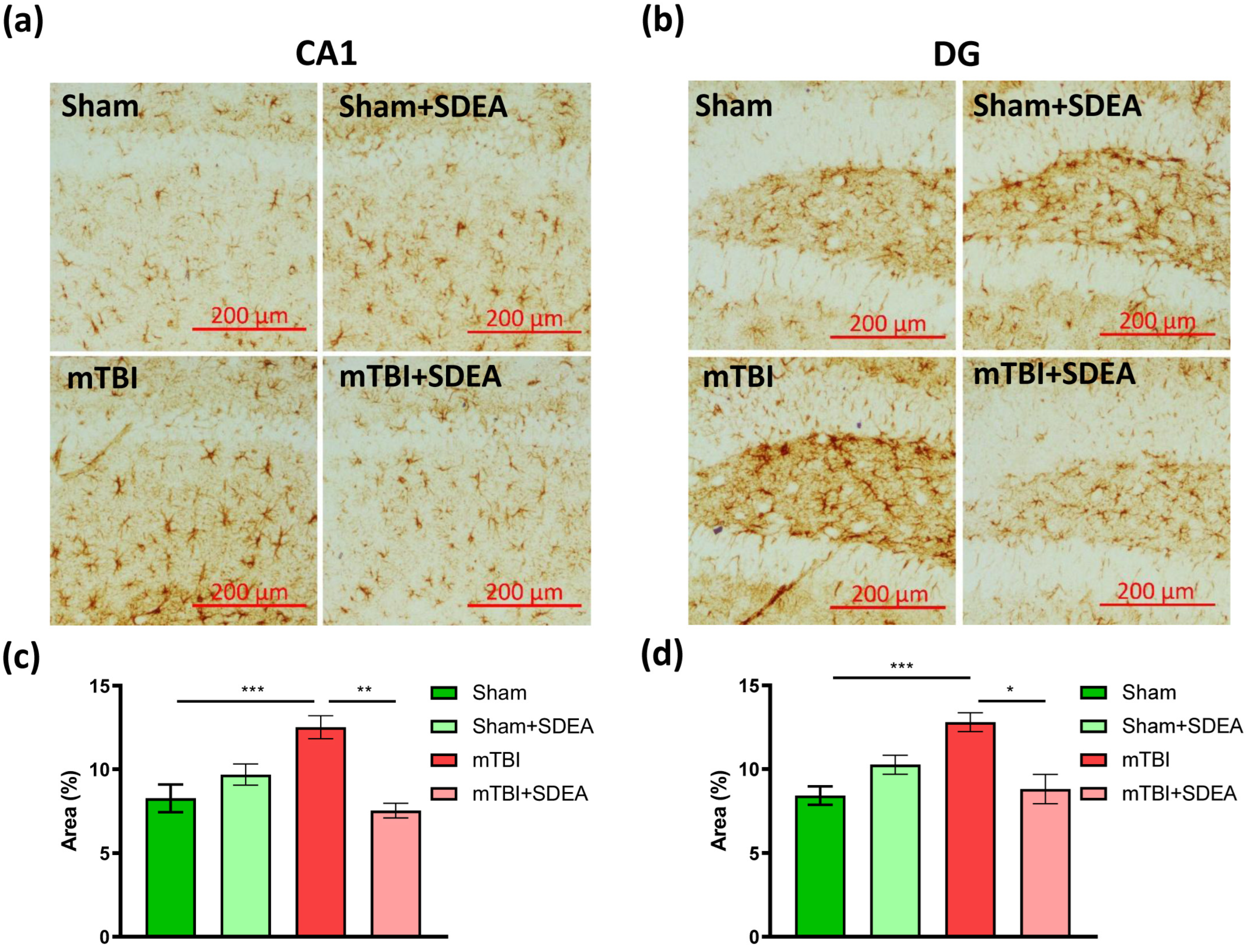

2.5. SDEA Suppresses mTBI-Induced Astroglial Activation

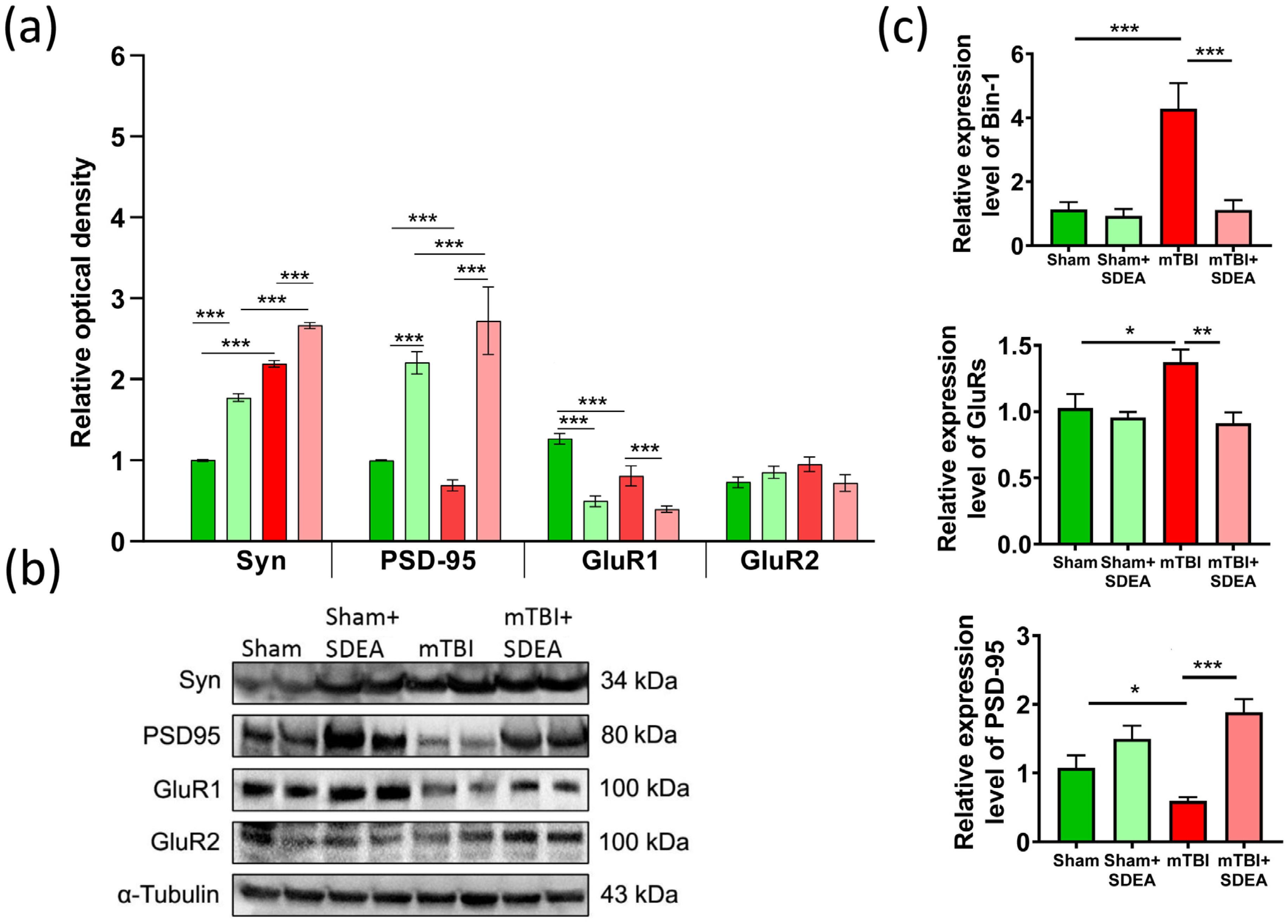

2.6. SDEA Normalizes BIN1 Expression and Restores Synaptic Marker Balance After mTBI

2.6.1. Synaptophysin

2.6.2. PSD-95

2.6.3. GluR1

2.6.4. GluR2

2.6.5. Bin-1 mRNA

2.6.6. Psd-95 mRNA

2.6.7. GluR Subunits mRNA

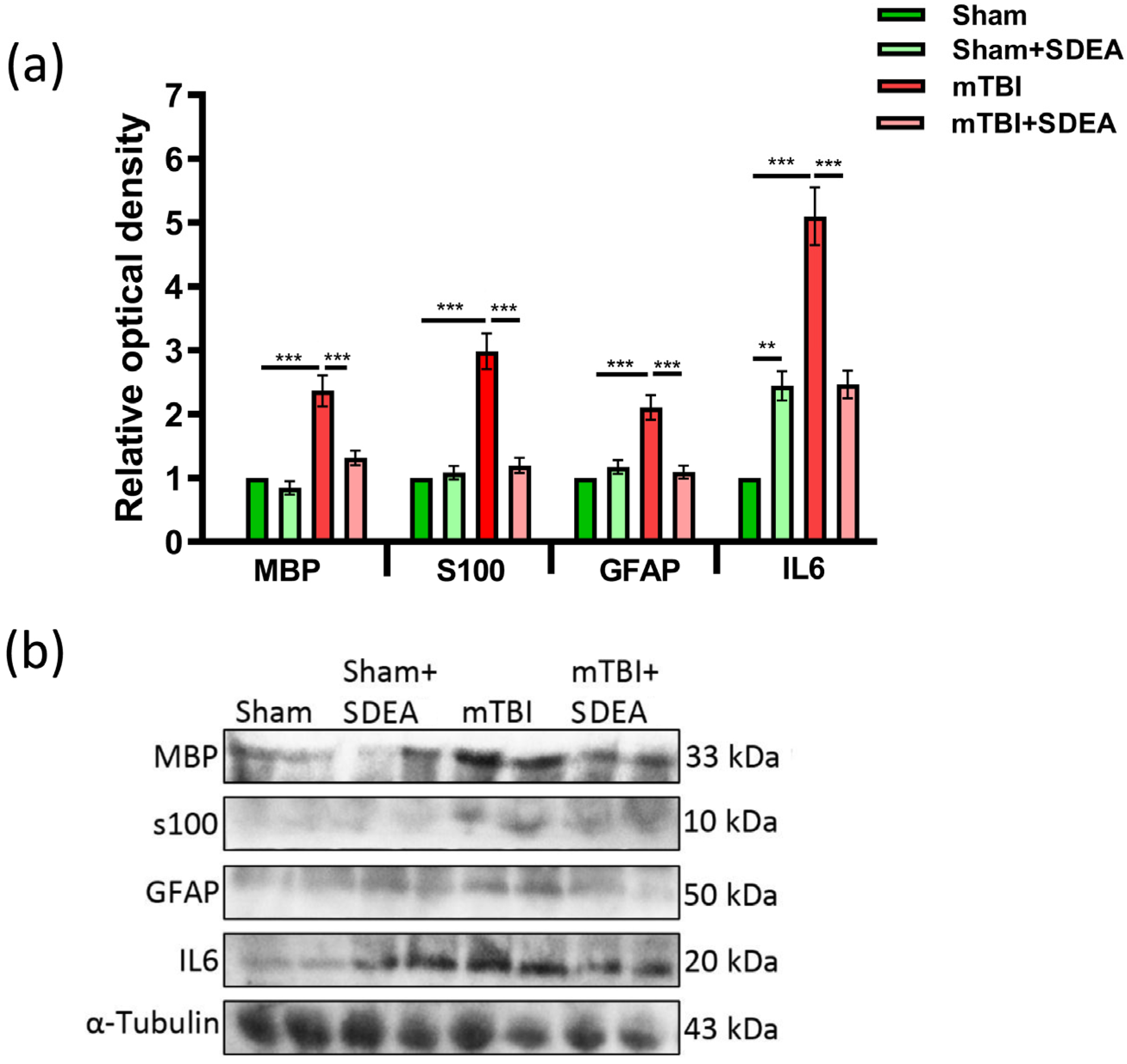

2.7. Serum Neuroglial Markers Following mTBI and SDEA Treatment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Isolation and Characterization of Stearidonic Acid Ethanolamide (SDEA)

4.2. Animals

4.3. mTBI Model

4.4. SDEA Preparation and Administration

4.5. Behavioral Testing

4.5.1. Y-Maze Spontaneous Alternation Test

4.5.2. Novel Object Recognition (NOR) Test

4.5.3. Elevated Plus Maze (EPM)

4.5.4. Tissue Collection

4.5.5. Immunohistochemistry

4.5.6. Image Acquisition and Quantification

4.5.7. Golgi-Cox Staining and Dendritic Spine Analysis

4.5.8. Western Blotting

4.5.9. Real-Time PCR

4.5.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| mTBI | mild traumatic brain injury |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| DG | dentate gyrus |

| CA1 | cornu ammonis area 1 |

| PUFA | polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| NAE | N-acylethanolamide |

| SDEA | stearidonic acid ethanolamide |

| DHA | docosahexaenoic acid |

| EPA | eicosapentaenoic acid |

| DHEA (synaptamide) | N-docosahexaenoylethanolamide |

| EPEA | N-eicosapentaenoylethanolamide |

| PEA | palmitoylethanolamide |

| GFAP | glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| S100B | S100 calcium-binding protein B |

| MBP | myelin basic protein |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1 beta |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| PSD-95 | postsynaptic density protein 95 |

| AMPAR | AMPA-type glutamate receptor |

| GluR1/GluR2 | AMPA receptor subunits |

| NMDAR1/NMDAR2 | NMDA receptor subunits |

| Arc | activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein |

| BIN1 | bridging integrator 1 |

| EPM | elevated plus maze |

| NOR | novel object recognition |

| DI | discrimination index |

| RI | recognition index |

| SAR | spontaneous alternation rate (Y-maze) |

| PVDF | polyvinylidene difluoride |

| ECL | enhanced chemiluminescence |

| RT-PCR | real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| SEM | standard error of the mean |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

References

- Haarbauer-Krupa, J.; Pugh, M.J.; Prager, E.M.; Harmon, N.; Wolfe, J.; Yaffe, K. Epidemiology of chronic effects of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 3235–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, A.J.; Tonks, J.; Potter, S.; Yates, P.J.; Reuben, A.; Ryland, H.; Williams, H. Neuropsychological assessment of mTBI in adults. In Traumatic Brain Injury: A Clinician’s Guide to Diagnosis, Management, and Rehabilitation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Prins, M.L.; Alexander, D.; Giza, C.C.; Hovda, D.A. Repeated mild traumatic brain injury: Mechanisms of cerebral vulnerability. J. Neurotrauma 2013, 30, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langlois, L.D.; Selvaraj, P.; Simmons, S.C.; Gouty, S.; Zhang, Y.; Nugent, F.S. Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury induces persistent alterations in spontaneous synaptic activity of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2022, 12, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burda, J.E.; Sofroniew, M.V. Reactive gliosis and the multicellular response to CNS damage and disease. Neuron 2014, 81, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakumar, A.R.; Tong, X.Y.; Ruiz-Cordero, R.; Bregy, A.; Bethea, J.R.; Bramlett, H.M.; Norenberg, M.D. Activation of NF-κB mediates astrocyte swelling and brain edema in traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michinaga, S.; Koyama, Y. Pathophysiological responses and roles of astrocytes in traumatic brain injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira, R.G.; Lira, M.; Cerpa, W. Traumatic brain injury: Mechanisms of glial response. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 740939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantoine, J.; Procès, A.; Villers, A.; Halliez, S.; Buée, L.; Ris, L.; Gabriele, S. Inflammatory molecules released by mechanically injured astrocytes trigger presynaptic loss in cortical neuronal networks. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 3885–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, H.; Niu, F.; Yang, M.; Ge, Q.; Lu, S.; Deng, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, B.; et al. Megf10-related engulfment of excitatory postsynapses by astrocytes following severe brain injury. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 29, 2873–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Chai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X. Astrocyte-mediated inflammatory responses in traumatic brain injury: Mechanisms and potential interventions. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1584577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Dai, L.; Xu, D.; Wang, Y.; Bai, L.; Chen, X.; Li, M.; Yang, S.; Tang, Y. Astrocyte secretes IL-6 to modulate PSD-95 palmitoylation in basolateral amygdala and depression-like behaviors induced by peripheral nerve injury. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 104, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, A.H.; Thayer, S.A. Synapse loss induced by interleukin-1β requires pre- and post-synaptic mechanisms. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012, 7, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngwenya, L.B.; Danzer, S.C. Impact of traumatic brain injury on neurogenesis. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y.; Spector, A.A. Synaptamide, endocannabinoid-like derivative of docosahexaenoic acid with cannabinoid-independent function. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2013, 88, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellitteri, R.; La Cognata, V.; Russo, C.; Patti, A.; Sanfilippo, C. Protective role of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic and their N-ethanolamide derivatives in olfactory glial cells affected by lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation. Molecules 2024, 29, 4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, G.; Alboni, S.; Cattane, N.; Marizzoni, M.; Saleri, S.; Arslanovski, N.; Mariani, N.; Kirkpatrick, M.; Cattaneo, A.; Pariante, C.M.; et al. The dietary ligands, omega-3 fatty acid endocannabinoids and short-chain fatty acids prevent cytokine-induced reduction of human hippocampal neurogenesis and alter the expression of genes involved in neuroinflammation and neuroplasticity. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 5338–5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y.; Spector, A.A. N-Docosahexaenoylethanolamine: A neurotrophic and neuroprotective metabolite of docosahexaenoic acid. Mol. Asp. Med. 2018, 64, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, T.; Chen, H.; Kim, H.Y. GPR110 (ADGRF1) mediates anti-inflammatory effects of N-docosahexaenoylethanolamine. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y.; Spector, A.A.; Xiong, Z.M. A synaptogenic amide N-docosahexaenoylethanolamide promotes hippocampal development. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2011, 96, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C. Mechanisms of action of (n-3) fatty acids. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 592S–599S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walf, A.A.; Frye, C.A. The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieur, E.A.; Jadavji, N.M. Assessing spatial working memory using the spontaneous alternation Y-maze test in aged male mice. Bio-Protocol 2019, 9, e3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueptow, L.M. Novel object recognition test for the investigation of learning and memory in mice. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2017, 126, 55718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; van Praag, H. Steps towards standardized quantification of adult neurogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebara, E.; Sultan, S.; Kocher-Braissant, J.; Toni, N. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis inversely correlates with microglia in conditions of voluntary running and aging. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramham, C.R.; Worley, P.F.; Moore, M.J.; Guzowski, J.F. The immediate early gene arc/arg3.1: Regulation, mechanisms, and function. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 11760–11767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penrod, R.D.; Kumar, J.; Smith, L.N.; McCalley, D.; Nentwig, T.B.; Hughes, B.W.; Barry, G.M.; Glover, K.; Taniguchi, M.; Cowan, C.W. Activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein (Arc/Arg3.1) regulates anxiety- and novelty-related behaviors. Genes Brain Behav. 2019, 18, e12561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runge, K.; Cardoso, C.; de Chevigny, A. Dendritic spine plasticity: Function and mechanisms. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2020, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, J.; Harris, K.M. Do thin spines learn to be mushroom spines that remember? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2007, 17, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, M.A.; Gualtieri, S.; Tarallo, A.P.; Verrina, M.C.; Calafiore, J.; Princi, A.; Lombardo, S.; Ranno, F.; Di Cello, A.; Gratteri, S.; et al. The Role of GFAP in Post-Mortem Analysis of Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 26, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janigro, D.; Mondello, S.; Posti, J.P.; Unden, J. GFAP and S100B: What you always wanted to know and never dared to ask. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 835597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glantz, L.A.; Gilmore, J.H.; Hamer, R.M.; Lieberman, J.A.; Jarskog, L.F. Synaptophysin and postsynaptic density protein 95 in the human prefrontal cortex from mid-gestation into early adulthood. Neuroscience 2007, 149, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollmann, M.; Hartley, M.; Heinemann, S. Ca2+ permeability of KA-AMPA--gated glutamate receptor channels depends on subunit composition. Science 1991, 252, 851–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Song, L.; Cummings, L.W.; Goldman, J.; Huganir, R.L.; Lee, H.K. Stabilization of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors at perisynaptic sites by GluR1-S845 phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20033–20038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagihara, H.; Ohira, K.; Toyama, K.; Miyakawa, T. Expression of the AMPA receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2 is associated with granule cell maturation in the dentate gyrus. Front. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glennon, E.B.; Lau, D.H.; Gabriele, R.M.C.; Taylor, M.F.; Troakes, C.; Opie-Martin, S.; Elliott, C.; Killick, R.; Hanger, D.P.; Perez-Nievas, B.G.; et al. Bridging Integrator-1 protein loss in Alzheimer’s disease promotes synaptic tau accumulation and disrupts tau release. Brain Commun. 2020, 2, fcaa011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dourlen, P.; Kilinc, D.; Landrieu, I.; Chapuis, J.; Lambert, J.C. BIN1 and Alzheimer’s disease: The tau connection. Trends Neurosci. 2025, 48, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, O.; Melo de Farias, A.R.; Pelletier, A.; Siedlecki-Wullich, D.; Landeira, B.S.; Gadaut, J.; Carrier, A.; Vreulx, A.C.; Guyot, K.; Shen, Y.; et al. The Alzheimer’s disease risk gene BIN1 regulates activity-dependent gene expression in human-induced glutamatergic neurons. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 2634–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Tsao, J.W.; Stanfill, A.G. The current state of biomarkers of mild traumatic brain injury. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e97105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oris, C.; Kahouadji, S.; Durif, J.; Bouvier, D.; Sapin, V. S100B, actor and biomarker of mild traumatic brain injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, I.; Marklund, N.; Czeiter, E.; Hutchinson, P.; Buki, A. Blood biomarkers for traumatic brain injury: A narrative review of current evidence. Brain Spine 2023, 4, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofroniew, M.V.; Vinters, H.V. Astrocytes: Biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loane, D.J.; Kumar, A. Microglia in the TBI brain: The good, the bad, and the dysregulated. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 275, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, D.W.; McGeachy, M.J.; Bayır, H.; Clark, R.S.; Loane, D.J.; Kochanek, P.M. The far-reaching scope of neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 171–191, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 572. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, V.E.; Stewart, J.E.; Begbie, F.D.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Smith, D.H.; Stewart, W. Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury. Brain 2013, 136, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shandra, O.; Winemiller, A.R.; Heithoff, B.P.; Munoz-Ballester, C.; George, K.K.; Benko, M.J.; Zuidhoek, I.A.; Besser, M.N.; Curley, D.E.; Edwards, G.F., III; et al. Repetitive diffuse mild traumatic brain injury causes an atypical astrocyte response and spontaneous recurrent seizures. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 1944–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, L.; Cristofori, I.; Weaver, S.M.; Chau, A.; Portelli, J.N.; Grafman, J. Cognitive decline in older adults with a history of traumatic brain injury. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khakh, B.S.; Sofroniew, M.V. Diversity of astrocyte functions and phenotypes in neural circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Swanson, R.A. Astrocytes and brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2003, 23, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papa, L.; Brophy, G.M.; Welch, R.D.; Lewis, L.M.; Braga, C.F.; Tan, C.N.; Ameli, N.J.; Lopez, M.A.; Haeussler, C.A.; Mendez Giordano, D.I.; et al. Time course and diagnostic accuracy of glial and neuronal blood biomarkers GFAP and UCH-L1 in a large cohort of trauma patients with and without mild traumatic brain injury. JAMA Neurol. 2016, 73, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchi, N.; Cavaglia, M.; Fazio, V.; Bhudia, S.; Hallene, K.; Janigro, D. Peripheral markers of blood-brain barrier damage. Clin. Chim. Acta 2004, 342, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, R.P.; Adelson, P.D.; Pierce, M.C.; Dulani, T.; Cassidy, L.D.; Kochanek, P.M. Serum neuron-specific enolase, S100B, and myelin basic protein concentrations after inflicted and noninflicted traumatic brain injury in children. J. Neurosurg. 2005, 103, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Bai, L.; Niu, X.; Wang, Z.; Yin, B.; Bai, G.; Zhang, D.; Gan, S.; Sun, C.; Wang, S.; et al. Elevated serum levels of inflammation-related cytokines in mild traumatic brain injury are associated with cognitive performance. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Nelson, C.D.; Li, X.; Winters, C.A.; Azzam, R.; Sousa, A.A.; Leapman, R.D.; Gainer, H.; Sheng, M.; Reese, T.S. PSD-95 is required to sustain the molecular organization of the postsynaptic density. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 6329–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opazo, P.; Sainlos, M.; Choquet, D. Regulation of AMPA receptor surface diffusion by PSD-95 slots. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2012, 22, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beattie, E.C.; Stellwagen, D.; Morishita, W.; Bresnahan, J.C.; Ha, B.K.; Von Zastrow, M.; Beattie, M.S.; Malenka, R.C. Control of synaptic strength by glial TNFα. Science 2002, 295, 2282–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardino, L.; Xapelli, S.; Silva, A.P.; Jakobsen, B.; Poulsen, F.R.; Oliveira, C.R.; Vezzani, A.; Malva, J.O.; Zimmer, J. Modulator effects of interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α on AMPA-induced excitotoxicity in mouse organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 6734–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, E.K. Selective neuronal vulnerability in the hippocampus: Relationship to neurological diseases and mechanisms for differential sensitivity of neurons to stress. In The Clinical Neurobiology of the Hippocampus; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lana, D.; Ugolini, F.; Giovannini, M.G. An overview on the differential interplay among neurons–astrocytes–microglia in CA1 and CA3 hippocampus in hypoxia/ischemia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 585833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkadhi, K.A. Cellular and molecular differences between area CA1 and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 6566–6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasic, V.; Schmidt, M.H.H. Resilience and vulnerability to pain and inflammation in the hippocampus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Chen, J. Moderate traumatic brain injury promotes neural precursor proliferation without increasing neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 239, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramham, C.R.; Alme, M.N.; Bittins, M.; Kuipers, S.D.; Nair, R.R.; Pai, B.; Panja, D.; Schubert, M.; Soule, J.; Tiron, A.; et al. The Arc of synaptic memory. Exp. Brain Res. 2010, 200, 125–140, Erratum in Exp. Brain Res. 2011, 209, 317. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haley, M.; Bertrand, J.; Anderson, V.T.; Fuad, M.; Frenguelli, B.G.; Corrêa, S.A.L.; Wall, M.J. Arc expression regulates long-term potentiation magnitude and metaplasticity in area CA1 of the hippocampus in ArcKR mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2023, 58, 4166–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, Z.U.; Carretero-Rey, M.; de León-López, C.A.M.; Navarro-Lobato, I. Memory-associated immediate early genes: Roles in synaptic function, memory processes, and neurological diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 15885–15915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, R.F.; Reagh, Z.M.; Chun, A.P.; Murray, E.A.; Yassa, M.A. Pattern separation and source memory engage distinct hippocampal and neocortical regions during retrieval. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heim, L.R.; Bader, M.; Edut, S.; Rachmany, L.; Baratz-Goldstein, R.; Lin, R.; Elpaz, A.; Qubty, D.; Bikovski, L.; Rubovitch, V.; et al. The invisibility of mild traumatic brain injury: Impaired cognitive performance as a silent symptom. J. Neurotrauma 2017, 34, 2518–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomar, A.; Polygalov, D.; McHugh, T.J. Differential impact of acute and chronic stress on CA1 spatial coding and gamma oscillations. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 710725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, M.; Navidhamidi, M.; Rezaei, F.; Azizikia, A.; Mehranfard, N. Anxiety and hippocampal neuronal activity: Relationship and potential mechanisms. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 22, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartsch, T.; Döhring, J.; Reuter, S.; Finke, C.; Rohr, A.; Brauer, H.; Deuschl, G.; Jansen, O. Selective neuronal vulnerability of human hippocampal CA1 neurons: Lesion evolution, temporal course, and pattern of hippocampal damage in diffusion-weighted MR imaging. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2015, 35, 1836–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.W.; Sun, D.; Davis, S.L.; Haswell, C.C.; Dennis, E.L.; Swanson, C.A.; Whelan, C.D.; Gutman, B.; Jahanshad, N.; Iglesias, J.E.; et al. Smaller hippocampal CA1 subfield volume in posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balvers, M.G.; Verhoeckx, K.C.; Plastina, P.; Wortelboer, H.M.; Meijerink, J.; Witkamp, R.F. Docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid are converted by 3T3-L1 adipocytes to N-acyl ethanolamines with anti-inflammatory properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1801, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazan, N.G. Cell survival matters: Docosahexaenoic acid signaling, neuroprotection and photoreceptors. Trends Neurosci. 2006, 29, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrtyshnaia, A.; Bondar, A.; Konovalova, S.; Sultanov, R.; Manzhulo, I. N-Docosahexanoylethanolamine reduces microglial activation and improves hippocampal plasticity in a murine model of neuroinflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringsevjen, H.; Egbenya, D.L.; Bieler, M.; Davanger, S.; Hussain, S. Activity-regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein (Arc) in presynaptic terminals and extracellular vesicles in hippocampal synapses. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1225533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riboldi, J.G.; Correa, J.; Renfijes, M.M.; Tintorelli, R.; Viola, H. Arc and BDNF mediated effects of hippocampal astrocytic glutamate uptake blockade on spatial memory stages. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, A.; Pirozzi, C.; Annunziata, C.; Morgese, M.G.; Senzacqua, M.; Severi, I.; Calignano, A.; Trabace, L.; Giordano, A.; Meli, R.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide counteracts brain fog improving depressive-like behaviour in obese mice: Possible role of synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 845–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccella, S.; Cristiano, C.; Romano, R.; Iannotta, M.; Belardo, C.; Farina, A.; Guida, F.; Piscitelli, F.; Palazzo, E.; Mazzitelli, M. Ultra-micronized palmitoylethanolamide rescues the cognitive decline-associated loss of neural plasticity in the neuropathic mouse entorhinal cortex-dentate gyrus pathway. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 121, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.A.; Katakura, M.; Kharebava, G.; Kevala, K.; Kim, H.Y. N-Docosahexaenoylethanolamine is a potent neurogenic factor for neural stem cell differentiation. J. Neurochem. 2013, 125, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyall, S.C. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and the brain: A review of the independent and shared effects of EPA, DPA and DHA. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- Bevins, R.A.; Besheer, J. Object recognition in rats and mice: A one-trial non-matching-to-sample learning task to study ‘recognition memory’. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 1306–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Egoraeva, A.; Manzhulo, I.; Ivashkevich, D.; Tyrtyshnaia, A. N-Stearidonoylethanolamine Restores CA1 Synaptic Integrity and Reduces Astrocytic Reactivity After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010471

Egoraeva A, Manzhulo I, Ivashkevich D, Tyrtyshnaia A. N-Stearidonoylethanolamine Restores CA1 Synaptic Integrity and Reduces Astrocytic Reactivity After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010471

Chicago/Turabian StyleEgoraeva, Anastasia, Igor Manzhulo, Darya Ivashkevich, and Anna Tyrtyshnaia. 2026. "N-Stearidonoylethanolamine Restores CA1 Synaptic Integrity and Reduces Astrocytic Reactivity After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010471

APA StyleEgoraeva, A., Manzhulo, I., Ivashkevich, D., & Tyrtyshnaia, A. (2026). N-Stearidonoylethanolamine Restores CA1 Synaptic Integrity and Reduces Astrocytic Reactivity After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010471