Mutant Tau (P301L) Enhances Global Protein Translation in Differentiated SH-SY5Y Cells by Upregulating mTOR Signalling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Mutant Tau (P301L) Affects the Nascent Proteome in Both Differentiated and Proliferative SH-SY5Y Cells

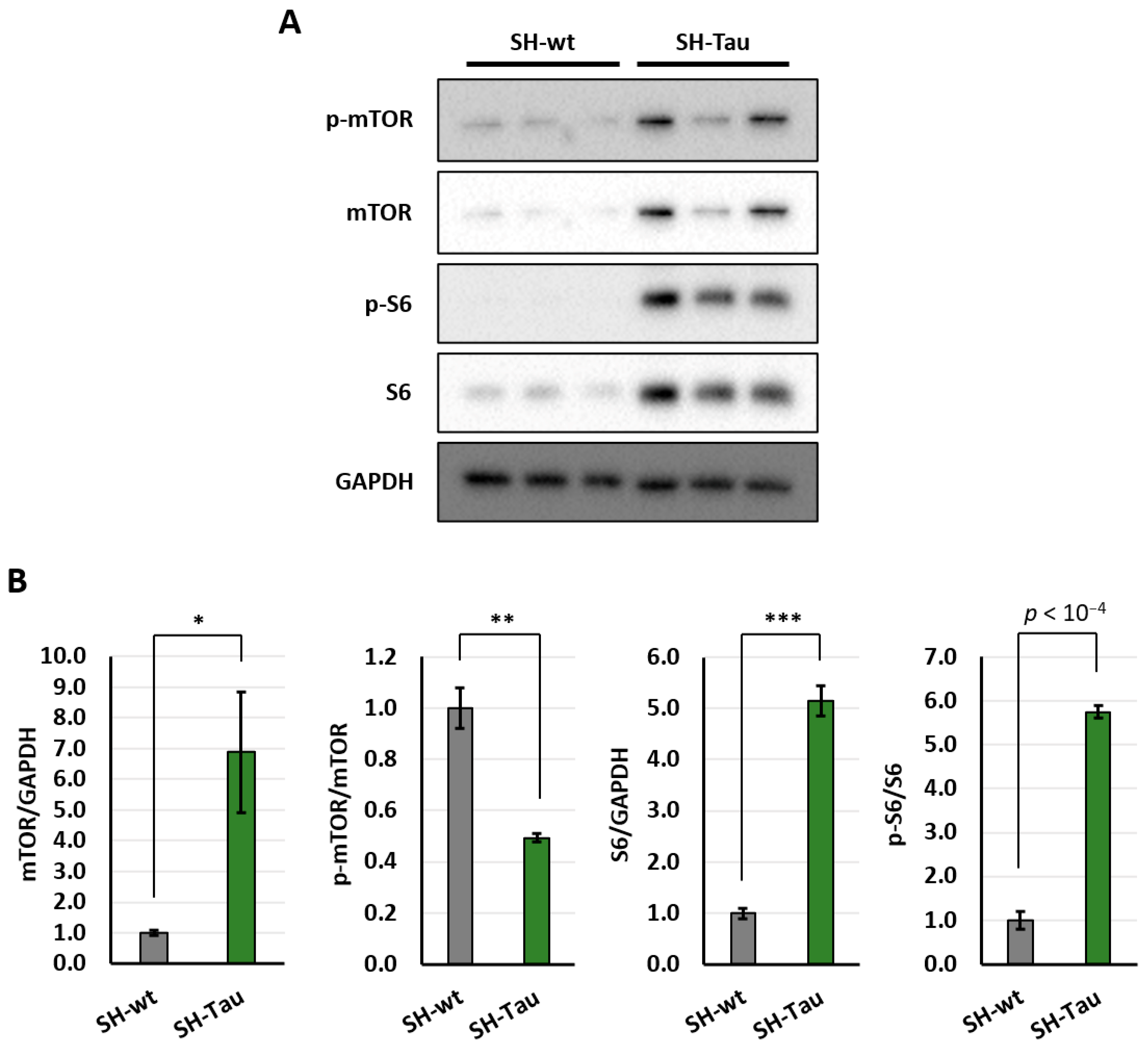

2.2. Mutant Tau (P301L) Protein Increases Activation of mTOR Pathway in Differentiated SH-SY5Y Neurons

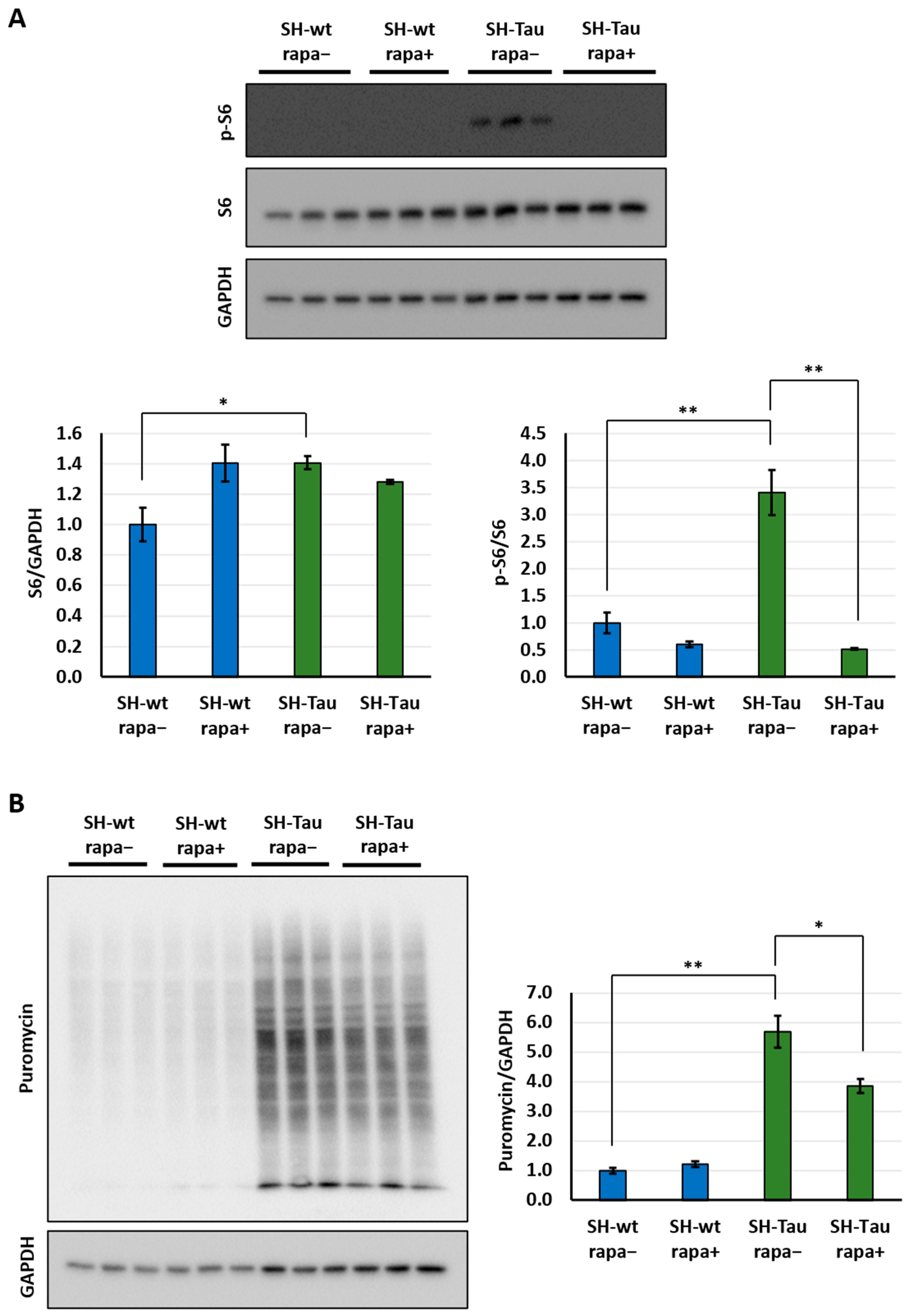

2.3. Mutant Tau (P301L) Upregulates Translation via mTOR Pathway in Differentiated SH-SY5Y Neurons

3. Discussion

Limitations and Follow-Ups

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Differentiation

4.2. Puromycin and Rapamycin Treatment

4.3. Western Blot Analyses

- Anti p-mTOR, rabbit polyclonal (Ser2448), (1:1000; #2971S, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA);

- Anti-mTOR, rabbit polyclonal (1:1000; #2972, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA);

- Anti-p-S6, rabbit polyclonal (Ser240/244), (1:1000; #2215, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA);

- Anti-S6, rabbit monoclonal (1:1000; #2217, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA);

- Anti-puromycin, mouse monoclonal (1:5000, #MABE343-AF647; Sigma-Aldrich).

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APP | amyloid precursor protein |

| DIV | day in vitro |

| FBS | foetal bovine serum |

| FTD | frontotemporal dementia |

| iPSC | induced pluripotent stem cell |

| mRNA | messenger RNA |

| mTOR | mechanistic/mammalian target of rapamycin |

| P/S | penicillin-streptomycin |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| RA | retinoic acid |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| s.e.m. | Standard error of the mean |

| SUnSET | Surface Sensing of Translation |

| TBST | Tris-buffered saline with Tween |

| tRNA | aminoacyl-transfer RNA |

References

- Creekmore, B.C.; Watanabe, R.; Lee, E.B. Neurodegenerative Disease Tauopathies. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2024, 19, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosler, T.W.; Tayaranian Marvian, A.; Brendel, M.; Nykanen, N.P.; Hollerhage, M.; Schwarz, S.C.; Hopfner, F.; Koeglsperger, T.; Respondek, G.; Schweyer, K.; et al. Four-repeat tauopathies. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019, 180, 101644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Noble, W.; Hanger, D.P. Roles of tau protein in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 133, 665–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Rojas, C.; Cabezas-Opazo, F.; Deaton, C.A.; Vergara, E.H.; Johnson, G.V.W.; Quintanilla, R.A. It’s all about tau. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019, 175, 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donison, N.; Palik, J.; Volkening, K.; Strong, M.J. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pathological tau phosphorylation in traumatic brain injury: Implications for chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samudra, N.; Lane-Donovan, C.; VandeVrede, L.; Boxer, A.L. Tau pathology in neurodegenerative disease: Disease mechanisms and therapeutic avenues. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.W.; Zhang, G.; Kuo, M.H. Frontotemporal Dementia P301L Mutation Potentiates but Is Not Sufficient to Cause the Formation of Cytotoxic Fibrils of Tau. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kabbani, M.A.; Kohler, C.; Zempel, H. Effects of P301L-TAU on post-translational modifications of microtubules in human iPSC-derived cortical neurons and TAU transgenic mice. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 20, 2348–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, B.; Christensen, K.R.; Richards, C.; Kneynsberg, A.; Mueller, R.L.; Morris, S.L.; Morfini, G.A.; Brady, S.T.; Kanaan, N.M. Frontotemporal Lobar Dementia Mutant Tau Impairs Axonal Transport through a Protein Phosphatase 1gamma-Dependent Mechanism. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 9431–9451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraelen, P.; Detrez, J.R.; Verschuuren, M.; Kuijlaars, J.; Nuydens, R.; Timmermans, J.P.; De Vos, W.H. Dysregulation of Microtubule Stability Impairs Morphofunctional Connectivity in Primary Neuronal Networks. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Mizuno, K.; Tiwari, S.S.; Proitsi, P.; Gomez Perez-Nievas, B.; Glennon, E.; Martinez-Nunez, R.T.; Giese, K.P. Alzheimer’s disease-related dysregulation of mRNA translation causes key pathological features with ageing. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, S.A.; Hamm, M.J.; Meier, S.E.; Weiss, B.E.; Nation, G.K.; Chishti, E.A.; Arango, J.P.; Chen, J.; Zhu, H.; Blalock, E.M.; et al. Tau drives translational selectivity by interacting with ribosomal proteins. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 137, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, S.; Bell, M.; Lyons, D.N.; Rodriguez-Rivera, J.; Ingram, A.; Fontaine, S.N.; Mechas, E.; Chen, J.; Wolozin, B.; LeVine, H., 3rd; et al. Pathological Tau Promotes Neuronal Damage by Impairing Ribosomal Function and Decreasing Protein Synthesis. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.T.; Benetatos, J.; van Roijen, M.; Bodea, L.G.; Gotz, J. Decreased synthesis of ribosomal proteins in tauopathy revealed by non-canonical amino acid labelling. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, H.T.; Taylor, D.; Kneynsberg, A.; Bodea, L.G.; Gotz, J. Altered ribosomal function and protein synthesis caused by tau. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2021, 9, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccamo, A.; Magri, A.; Medina, D.X.; Wisely, E.V.; Lopez-Aranda, M.F.; Silva, A.J.; Oddo, S. mTOR regulates tau phosphorylation and degradation: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies. Aging Cell 2013, 12, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, F.; Tramutola, A.; Foppoli, C.; Head, E.; Perluigi, M.; Butterfield, D.A. mTOR in Down syndrome: Role in Ass and tau neuropathology and transition to Alzheimer disease-like dementia. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 114, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Lu, Y.; Piao, W.; Jin, H. The Translational Regulation in mTOR Pathway. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, V.; Singh, A.; Bhatt, M.; Tonk, R.K.; Azizov, S.; Raza, A.S.; Sengupta, S.; Kumar, D.; Garg, M. Multifaceted role of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway in human health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccamo, A.; Branca, C.; Talboom, J.S.; Shaw, D.M.; Turner, D.; Ma, L.; Messina, A.; Huang, Z.; Wu, J.; Oddo, S. Reducing Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinase 1 Expression Improves Spatial Memory and Synaptic Plasticity in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 14042–14056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccamo, A.; Majumder, S.; Richardson, A.; Strong, R.; Oddo, S. Molecular interplay between mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), amyloid-beta, and Tau: Effects on cognitive impairments. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 13107–13120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.C.; Nandi, G.A.; Tentarelli, S.; Gurrell, I.K.; Jamier, T.; Lucente, D.; Dickerson, B.C.; Brown, D.G.; Brandon, N.J.; Haggarty, S.J. Prolonged tau clearance and stress vulnerability rescue by pharmacological activation of autophagy in tauopathy neurons. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querfurth, H.; Lee, H.K. Mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) complexes in neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurodegener. 2021, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueed, Z.; Tandon, P.; Maurya, S.K.; Deval, R.; Kamal, M.A.; Poddar, N.K. Tau and mTOR: The Hotspots for Multifarious Diseases in Alzheimer’s Development. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, G.S.; Norambuena, A. Dysregulation of mTOR by tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Cytoskeleton 2024, 81, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuniga, G.; Katsumura, S.; De Mange, J.; Ramirez, P.; Atrian, F.; Morita, M.; Frost, B. Pathogenic tau induces an adaptive elevation in mRNA translation rate at early stages of disease. Aging cell 2024, 23, e14245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, H.; Moreno, J.A.; Verity, N.; Halliday, M.; Mallucci, G.R. PERK inhibition prevents tau-mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 130, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, L.M.; De Bastiani, M.A.; Rico, E.P.; Schonhofen, P.; Pfaffenseller, B.; Wollenhaupt-Aguiar, B.; Grun, L.; Barbe-Tuana, F.; Zimmer, E.R.; Castro, M.A.A.; et al. Cholinergic Differentiation of Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cell Line and Its Potential Use as an In vitro Model for Alzheimer’s Disease Studies. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 7355–7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bergen, M.; Barghorn, S.; Biernat, J.; Mandelkow, E.M.; Mandelkow, E. Tau aggregation is driven by a transition from random coil to beta sheet structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1739, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, E.K.; Clavarino, G.; Ceppi, M.; Pierre, P. SUnSET, a nonradioactive method to monitor protein synthesis. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviner, R. The science of puromycin: From studies of ribosome function to applications in biotechnology. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1074–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, N.; Sonenberg, N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 1926–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapur, M.; Monaghan, C.E.; Ackerman, S.L. Regulation of mRNA Translation in Neurons-A Matter of Life and Death. Neuron 2017, 96, 616–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayanandan, R.; Van Slegtenhorst, M.; Mack, T.G.; Ko, L.; Yen, S.H.; Leroy, K.; Brion, J.P.; Anderton, B.H.; Hutton, M.; Lovestone, S. Mutations in tau reduce its microtubule binding properties in intact cells and affect its phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 1999, 446, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, M.; Radford, H.; Zents, K.A.M.; Molloy, C.; Moreno, J.A.; Verity, N.C.; Smith, E.; Ortori, C.A.; Barrett, D.A.; Bushell, M.; et al. Repurposed drugs targeting eIF2alpha-P-mediated translational repression prevent neurodegeneration in mice. Brain A J. Neurol. 2017, 140, 1768–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portillo, M.; Eremenko, E.; Kaluski, S.; Garcia-Venzor, A.; Onn, L.; Stein, D.; Slobodnik, Z.; Zaretsky, A.; Ueberham, U.; Einav, M.; et al. SIRT6-CBP-dependent nuclear Tau accumulation and its role in protein synthesis. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoody, S.; Asgari Taei, A.; Khodabakhsh, P.; Dargahi, L. mTOR signaling and Alzheimer’s disease: What we know and where we are? CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffington, S.A.; Huang, W.; Costa-Mattioli, M. Translational control in synaptic plasticity and cognitive dysfunction. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 37, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, J.; Kouser, M.; Powell, C.M. Systemic inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibits fear memory reconsolidation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2008, 90, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehninger, D.; Han, S.; Shilyansky, C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Ramesh, V.; Silva, A.J. Reversal of learning deficits in a Tsc2+/− mouse model of tuberous sclerosis. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, S. The role of mTOR signaling in Alzheimer disease. Front. Biosci. 2012, 4, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oddo, S.; Caccamo, A.; Cheng, D.; Jouleh, B.; Torp, R.; LaFerla, F.M. Genetically augmenting tau levels does not modulate the onset or progression of Abeta pathology in transgenic mice. J. Neurochem. 2007, 102, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, M.; Zempel, H. SH-SY5Y-derived neurons: A human neuronal model system for investigating TAU sorting and neuronal subtype-specific TAU vulnerability. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xicoy, H.; Wieringa, B.; Martens, G.J. The SH-SY5Y cell line in Parkinson’s disease research: A systematic review. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Seo, J.Y.; Ryu, H.G.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, K.T. BDNF-induced local translation of GluA1 is regulated by HNRNP A2/B1. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabd2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazejczyk, M.; Macias, M.; Korostynski, M.; Firkowska, M.; Piechota, M.; Skalecka, A.; Tempes, A.; Koscielny, A.; Urbanska, M.; Przewlocki, R.; et al. Kainic Acid Induces mTORC1-Dependent Expression of Elmo1 in Hippocampal Neurons. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 2562–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cipriano, G.L.; Floramo, A.; Argento, V.; Oddo, S.; Artimagnella, O. Mutant Tau (P301L) Enhances Global Protein Translation in Differentiated SH-SY5Y Cells by Upregulating mTOR Signalling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010455

Cipriano GL, Floramo A, Argento V, Oddo S, Artimagnella O. Mutant Tau (P301L) Enhances Global Protein Translation in Differentiated SH-SY5Y Cells by Upregulating mTOR Signalling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):455. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010455

Chicago/Turabian StyleCipriano, Giovanni Luca, Alessia Floramo, Veronica Argento, Salvatore Oddo, and Osvaldo Artimagnella. 2026. "Mutant Tau (P301L) Enhances Global Protein Translation in Differentiated SH-SY5Y Cells by Upregulating mTOR Signalling" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010455

APA StyleCipriano, G. L., Floramo, A., Argento, V., Oddo, S., & Artimagnella, O. (2026). Mutant Tau (P301L) Enhances Global Protein Translation in Differentiated SH-SY5Y Cells by Upregulating mTOR Signalling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010455