Lathyrol Exerts Anti-Pulmonary Fibrosis Effects by Activating PPARγ to Inhibit the TGF-β/Smad Pathway

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Lathyrol Reduced BLM-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis in Mice

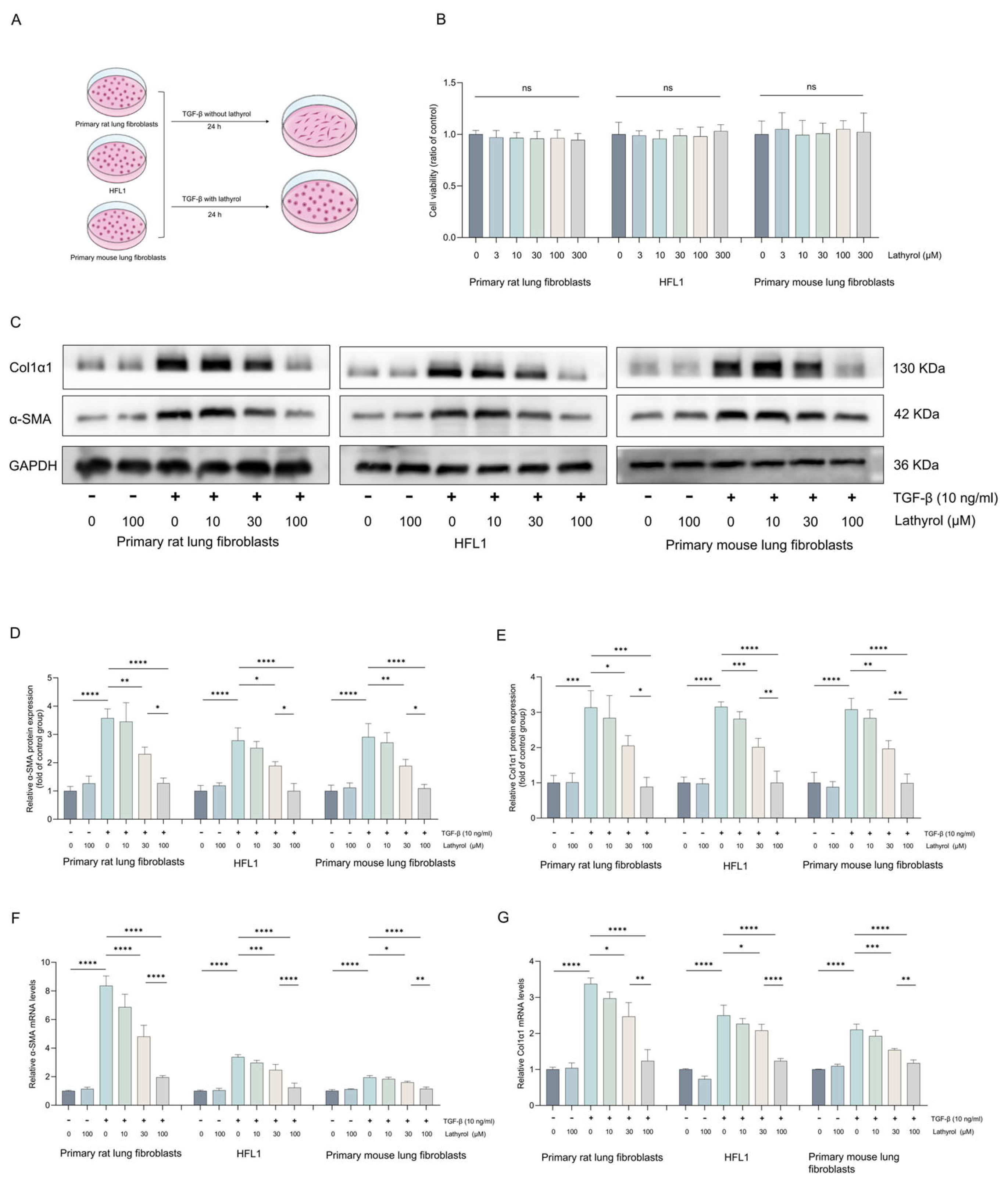

2.2. Lathyrol Inhibited TGF-β1-Induced Fibroblast-to-Myofibroblast Transdifferentiation

2.3. Lathyrol Activated the PPARγ in Fibroblasts

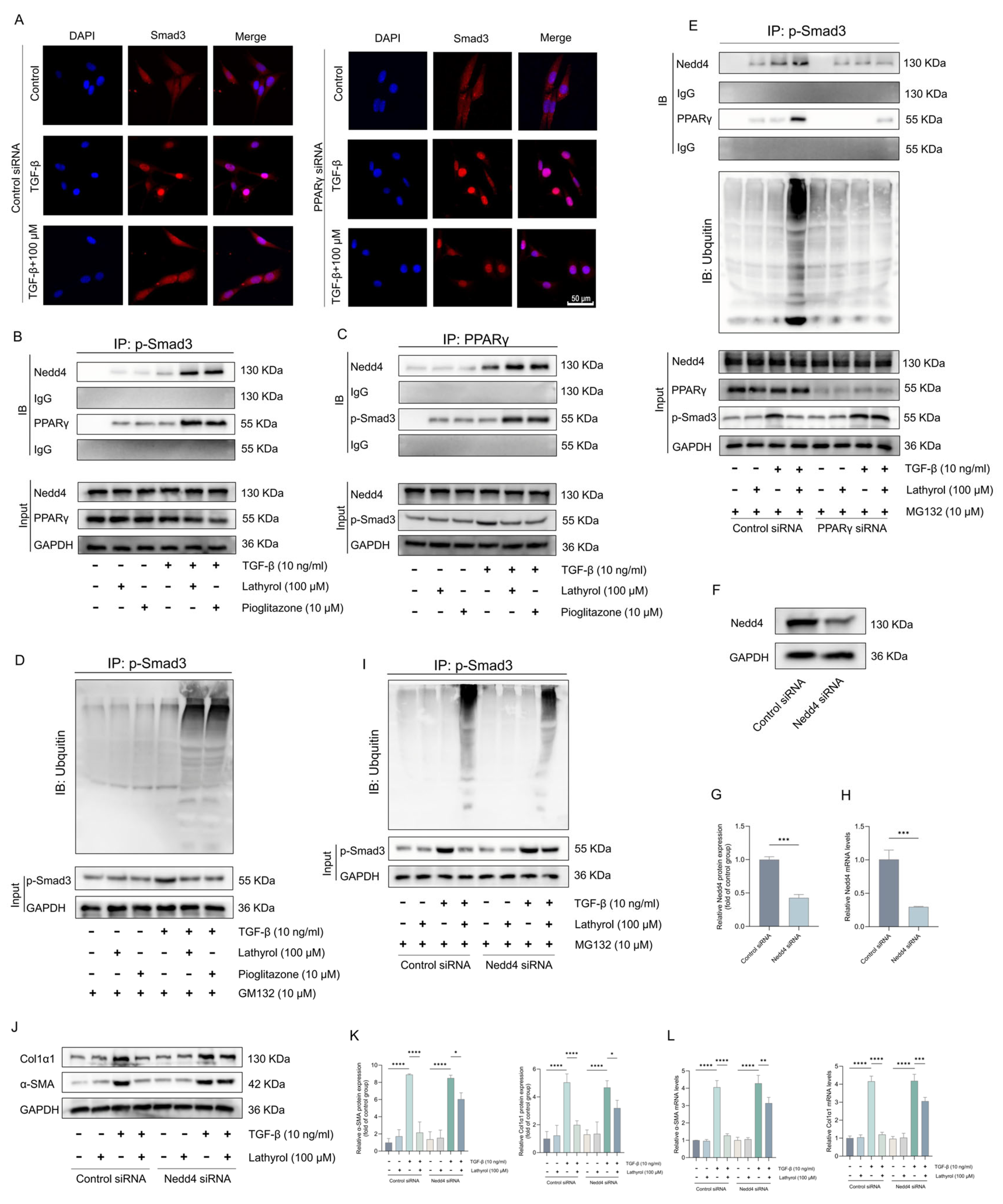

2.4. PPARγ Mediated the Inhibition of Myofibroblast Transformation by Lathyrol

2.5. Lathyrol Inhibits the TGF-β/Smad Pathway by Activating PPARγ

2.6. PPARγ Mediated the Anti-Pulmonary Fibrosis Effects of Lathyrol In Vivo

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Animals and Pulmonary Fibrosis Models

4.2. Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) Staining, Masson’s Trichrome Staining, and Ashcroft Scoring

4.3. Hydroxyproline Assay

4.4. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

4.5. WB

4.6. Cell Extraction and Culture

4.7. Cell Viability Assay

4.8. RNA-Seq and Data Analysis

4.9. Immunofluorescence

4.10. siRNA Transfection

4.11. Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

4.12. Ubiquitination Assay

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IPF | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| BLM | Bleomycin |

| HE | Hematoxylin and eosin staining |

| RT-qPCR | Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| WB | Western blotting |

| HFL1 | Human fetal lung fibroblasts |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| Co-IP | Co-immunoprecipitation |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| p-Smad3 | Phosphorylated Smad3 |

| α-SMA | Alpha smooth muscle actin |

References

- Lederer, D.J.; Martinez, F.J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1811–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, B.J.; Ryter, S.W.; Rosas, I.O. Pathogenic Mechanisms Underlying Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2022, 17, 515–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, R.K.; Schwartz, D.A. Revealing the Secrets of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zuo, H.; Yang, Z.; Qu, J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: An Update on Pathogenesis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 797292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richeldi, L.; Collard, H.R.; Jones, M.G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet 2017, 389, 1941–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, P.; Kropski, J.A.; Jones, M.G.; Lee, J.S.; Rossi, G.; Karampitsakos, T.; Maher, T.M.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Ryerson, C.J. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Disease mechanisms and drug development. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 222, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, M.A.; Sheppard, D. TGF-beta activation and function in immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 51–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massague, J.; Sheppard, D. TGF-beta signaling in health and disease. Cell 2023, 186, 4007–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Fu, M.; Wang, M.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Targeting TGF-beta signal transduction for fibrosis and cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Alexander, P.B.; Wang, X.F. TGF-beta Family Signaling in the Control of Cell Proliferation and Survival. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a022145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, K.; Hao, D.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, H.; Chen, H. Pulmonary fibrosis: Pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. MedComm 2024, 5, e744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massague, J. TGFbeta signalling in context. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, M.; Tang, P.M.; Huang, X.R.; Sun, S.F.; You, Y.K.; Xiao, J.; Lv, L.L.; Xu, A.P.; Lan, H.Y. TGF-beta Mediates Renal Fibrosis via the Smad3-Erbb4-IR Long Noncoding RNA Axis. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massague, J. How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Zhu, Y.J.; Yang, X.; Guo, Z.J.; Xu, W.B.; Tian, X.L. Effect of TGF-beta/Smad signaling pathway on lung myofibroblast differentiation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2007, 28, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Lai, X.; Yang, L.; Ye, F.; Huang, C.; Qiu, Y.; Lin, S.; Pu, L.; Wang, Z.; Huang, W. Asporin Promotes TGF-beta-induced Lung Myofibroblast Differentiation by Facilitating Rab11-Dependent Recycling of TbetaRI. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2022, 66, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Song, B.; Peng, F.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, S. Zangsiwei prevents particulate matter-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis by inhibiting the TGF-beta/SMAD pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 337, 118752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Lin, Y.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, S.; Qiu, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, Z.; Lai, X. Suppression of OGN in lung myofibroblasts attenuates pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting integrin alphav-mediated TGF-beta/Smad pathway activation. Matrix Biol. 2024, 132, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Liu, J.; Yan, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; Wen, X.; Jiang, Z.; Li, H.; Li, J.; et al. 13-Methylpalmatine alleviates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by suppressing the ITGA5/TGF-beta/Smad signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 2025, 140, 156545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, R.; Wang, Q.; Yu, M.; Zeng, Y.; Wen, S.; Liu, T.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Chang, S.; Chi, H.; et al. AAV9-HGF cooperating with TGF-beta/Smad inhibitor attenuates silicosis fibrosis via inhibiting ferroptosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaigne, D.; Butruille, L.; Staels, B. PPAR control of metabolism and cardiovascular functions. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, M.; Lefebvre, P.; Staels, B. Molecular mechanism of PPARalpha action and its impact on lipid metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 720–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Zhang, L.; Jin, C.; Xiong, Y.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Chen, K. Pomegranate flower extract bidirectionally regulates the proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis of 3T3-L1 cells through regulation of PPARgamma expression mediated by PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Gong, L.; Zhu, H.; Pu, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, G. Curcumin Inhibits Transforming Growth Factor beta Induced Differentiation of Mouse Lung Fibroblasts to Myofibroblasts. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derrett-Smith, E.; Clark, K.; Xu, S.; Abraham, D.J.; Hoyles, R.K.; Lacombe, O.; Broqua, P.; Junien, J.L.; Konstantinova, I.; Ong, V.H.; et al. The pan-PPAR agonist lanifibranor reduces development of lung fibrosis and attenuates cardiorespiratory manifestations in a transgenic mouse model of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, Y.; Maeno, T.; Aoyagi, K.; Ueno, M.; Aoki, F.; Aoki, N.; Nakagawa, J.; Sando, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Suga, T.; et al. Pioglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligand, suppresses bleomycin-induced acute lung injury and fibrosis. Respiration 2009, 77, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fan, H.; Wang, X.; Zhao, A.; Tian, Y.; Yang, G.; Li, C.; Wei, J.; Yao, W.; et al. PPARgamma/LXRalpha axis mediated phenotypic plasticity of lung fibroblasts in silica-induced experimental silicosis. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 292, 118272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Liu, Y.; Zhai, L.; Wang, L.; Lin, Z.; Wang, S. Activating Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPARs): A New Sight for Chrysophanol to Treat Paraquat-Induced Lung Injury. Inflammation 2016, 39, 928–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirollahi, V.; Wasnick, R.M.; Biasin, V.; Vazquez-Armendariz, A.I.; Chu, X.; Moiseenko, A.; Weiss, A.; Wilhelm, J.; Zhang, J.S.; Kwapiszewska, G.; et al. Metformin induces lipogenic differentiation in myofibroblasts to reverse lung fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milam, J.E.; Keshamouni, V.G.; Phan, S.H.; Hu, B.; Gangireddy, S.R.; Hogaboam, C.M.; Standiford, T.J.; Thannickal, V.J.; Reddy, R.C. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit profibrotic phenotypes in human lung fibroblasts and bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2008, 294, L891–L901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, L.; Sun, D.; Wang, H.; Song, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, L. Synthesis of Lathyrol PROTACs and Evaluation of Their Anti-Inflammatory Activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Tai, L.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, J. Lathyrol reduces the RCC invasion and incidence of EMT via affecting the expression of AR and SPHK2 in RCC mice. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Pan, C.; Zeng, L. Lathyrol promotes ER stress-induced apoptosis and proliferation inhibition in lung cancer cells by targeting SERCA2. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 158, 114123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Y.; Bai, Y.; Liang, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Guo, J.; Cai, X.; Hu, X.; Fang, Y.; Ding, X.; et al. Ingenol ameliorates silicosis via targeting the PTGS2/PI3K/AKT signaling axis: Implications for therapeutic intervention. Cell. Signal. 2025, 131, 111780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Song, Y. Lathyrol inhibits the proliferation of Renca cells by altering expression of TGF-β/Smad pathway components and subsequently affecting the cell cycle. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1629962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beekmann, K.; Rubio, L.; de Haan, L.H.; Actis-Goretta, L.; van der Burg, B.; van Bladeren, P.J.; Rietjens, I.M.C.M. The effect of quercetin and kaempferol aglycones and glucuronides on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma). Food Funct. 2015, 6, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizaibek, M.; Wubuli, A.; Gu, Z.; Bahetjan, D.; Tursinbai, L.; Nurhamit, K.; Chen, B.; Wang, J.; Tahan, O.; Cao, P. Effects of an ethyl acetate extract of Daphne altaica stem bark on the cell cycle, apoptosis and expression of PPARgamma in Eca-109 human esophageal carcinoma cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surse, V.M.; Gupta, J.; Tikoo, K. Esculetin induced changes in Mmp13 and Bmp6 gene expression and histone H3 modifications attenuate development of glomerulosclerosis in diabetic rats. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2011, 46, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zeng, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Wu, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhang, Q.; Jia, J.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, X.; et al. Oleic acid alleviates LPS-induced acute kidney injury by restraining inflammation and oxidative stress via the Ras/MAPKs/PPAR-gamma signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 2022, 94, 153818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvier, L.; Chouvarine, P.; Legchenko, E.; Hoffmann, N.; Geldner, J.; Borchert, P.; Jonigk, D.; Mozes, M.M.; Hansmann, G. PPARgamma Links BMP2 and TGFbeta1 Pathways in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells, Regulating Cell Proliferation and Glucose Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1118–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Ye, Z.; Mei, S.; Zhang, M.; Wu, M.; Lin, F.; Yu, W.; Li, W.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, F. PRMT1-mediated methylation of UBE2m promoting calcium oxalate crystal-induced kidney injury by inhibiting fatty acid metabolism. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, B.C.; Borok, Z. TGF-beta-induced EMT: Mechanisms and implications for fibrotic lung disease. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2007, 293, L525–L534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Yang, X.; Yu, Q.; Luo, Q.; Ju, C.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Liang, Z.; Xia, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Overexpression of STX11 alleviates pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting fibroblast activation via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, J.; Wagner, J.A. Physiological and therapeutic roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2002, 4, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucattelli, M.; Fineschi, S.; Selvi, E.; Gonzalez, E.G.; Bartalesi, B.; De Cunto, G.; Lorenzini, S.; Galeazzi, M.; Lungarella, G. Ajulemic acid exerts potent anti-fibrotic effect during the fibrogenic phase of bleomycin lung. Respir. Res. 2016, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, P.; Zhao, G.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Tong, T. Upregulation of SIRT1 by 17beta-estradiol depends on ubiquitin-proteasome degradation of PPAR-gamma mediated by NEDD4-1. Protein Cell 2013, 4, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Wang, R.; Lama, R.; Wang, X.; Floyd, Z.E.; Park, E.A.; Liao, F.-F. Ubiquitin Ligase NEDD4 Regulates PPARgamma Stability and Adipocyte Differentiation in 3T3-L1 Cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.N.; Tian, Z.W.; Tian, T.; Zhu, Z.-P.; Zhao, W.-J.; Tian, H.; Cheng, X.; Hu, F.-J.; Hu, M.-L.; Tian, S.; et al. TMBIM1 is an inhibitor of adipogenesis and its depletion promotes adipocyte hyperplasia and improves obesity-related metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1640–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yao, Q.; Xiao, L.; Ma, W.; Li, F.; Lai, B.; Wang, N. PPARgamma induces NEDD4 gene expression to promote autophagy and insulin action. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jiang, W.; Hu, T.; Long, Y.; Shen, Y. NEDD4 and NEDD4L: Ubiquitin Ligases Closely Related to Digestive Diseases. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Alarcon, C.; Sapkota, G.; Rahman, S.; Chen, P.-Y.; Goerner, N.; Macias, M.J.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Massagué, J. Ubiquitin ligase Nedd4L targets activated Smad2/3 to limit TGF-beta signaling. Mol. Cell 2009, 36, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitz, D.; Duerr, J.; Mulugeta, S.; Agircan, A.S.; Zimmermann, S.; Kawabe, H.; Dalpke, A.H.; Beers, M.F.; Mall, M.A. Congenital Deletion of Nedd4-2 in Lung Epithelial Cells Causes Progressive Alveolitis and Pulmonary Fibrosis in Neonatal Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitz, D.; Konietzke, P.; Wagner, W.L.; Mertiny, M.; Benke, C.; Schneider, T.; Morty, R.E.; Dullin, C.; Stiller, W.; Kauczor, H.-U.; et al. Longitudinal microcomputed tomography detects onset and progression of pulmonary fibrosis in conditional Nedd4-2 deficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2024, 327, L917–L929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Z.; Li, D.; Xu, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, B.; Sun, C.; Dong, W.; Zhang, Y. CUL4B, NEDD4, and UGT1As involve in the TGF-beta signalling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann. Hepatol. 2016, 15, 568–576. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Wei, J.; Kim, S.; Barak, Y.; Mori, Y.; Varga, J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma abrogates Smad-dependent collagen stimulation by targeting the p300 transcriptional coactivator. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2009, 23, 2968–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gressner, O.A.; Lahme, B.; Rehbein, K.; Siluschek, M.; Weiskirchen, R.; Gressner, A.M. Pharmacological application of caffeine inhibits TGF-beta-stimulated connective tissue growth factor expression in hepatocytes via PPARgamma and SMAD2/3-dependent pathways. J. Hepatol. 2008, 49, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Q. The phytochemistry, pharmacokinetics, pharmacology and toxicity of Euphorbia semen. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 227, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Peng, Z.; Luo, S.; Zhang, S.; Li, B.; Zhou, C.; Fan, H. Aesculin protects against DSS-Induced colitis though activating PPARgamma and inhibiting NF-small ka, CyrillicB pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 857, 172453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene. | Forward [5′-3′] | Reverse [5′-3′] |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse GAPDH | GGTTGTCTCCTGCGACTTCA | TGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTACTCC |

| Mouse α-SMA | TGGCTATTCAGGCTGTGCTGTC | CAATCTCACGCTCGGCAGTAGT |

| Mouse Col1α1 | GAGCGGAGAGTACTGGATCG | GCTTCTTTTCCTTGGGGTTC |

| Mouse PPARɣ | AGCCCTTTACCACAGTTGATTTCTCC | GCAGGTTCTACTTTGATCGCACTTTG |

| Rat GAPDH | TGTCACCAACTGGGACGATA | GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAA |

| Rat α-SMA | GCGTGGCTATTCCTTCGTGACTAC | CATCAGGCAGTTCGTAGCTCTTCTC |

| Rat Col1α1 | TGTTGGTCCTGCTGGCAAGAATG | GTCACCTTGTTCGCCTGTCTCAC |

| Human GAPDH | CAGGAGGCATTGCTGATGAT | GAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTT |

| Human α-SMA | TCCGGAGCGAAATACTCTG | CCCGGCTTCATCGTATTCCT |

| Human Col1α1 | CCACCAATCACCTGCGTACA | CACGTCATCGCACAACACCT |

| Mouse Nedd4 | CCGAGTATAGTGGTCAGGCTGTC | TGGCTGGTGGCTGGATTTCC |

| Antibody | Manufacturer |

|---|---|

| GAPDH | Proteintech, Wuhan, China |

| α-SMA | Proteintech, Wuhan, China |

| Col1α1 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK |

| PPARγ | Abcam, Cambridge, UK |

| Smad3 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK |

| p-Smad3 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| Nedd4 | Proteintech, Wuhan, China |

| Lamin B1 | Proteintech, Wuhan, China |

| Ubiquitin | Proteintech, Wuhan, China |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, Q.; Liao, M.-L.; Luo, Y.-Y.; Li, S.; You, G.; Huang, C.-M.; Liu, M.-H.; Liu, W.; Tang, S.-Y. Lathyrol Exerts Anti-Pulmonary Fibrosis Effects by Activating PPARγ to Inhibit the TGF-β/Smad Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010387

Zeng Q, Liao M-L, Luo Y-Y, Li S, You G, Huang C-M, Liu M-H, Liu W, Tang S-Y. Lathyrol Exerts Anti-Pulmonary Fibrosis Effects by Activating PPARγ to Inhibit the TGF-β/Smad Pathway. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010387

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Qian, Min-Lin Liao, Yu-Yang Luo, Shuang Li, Gao You, Chong-Mei Huang, Min-Hui Liu, Wei Liu, and Si-Yuan Tang. 2026. "Lathyrol Exerts Anti-Pulmonary Fibrosis Effects by Activating PPARγ to Inhibit the TGF-β/Smad Pathway" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010387

APA StyleZeng, Q., Liao, M.-L., Luo, Y.-Y., Li, S., You, G., Huang, C.-M., Liu, M.-H., Liu, W., & Tang, S.-Y. (2026). Lathyrol Exerts Anti-Pulmonary Fibrosis Effects by Activating PPARγ to Inhibit the TGF-β/Smad Pathway. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010387