Temporal Dynamics of Gene Expression and Metabolic Rewiring in Wild Barley (Hordeum spontaneum) Under Salt Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

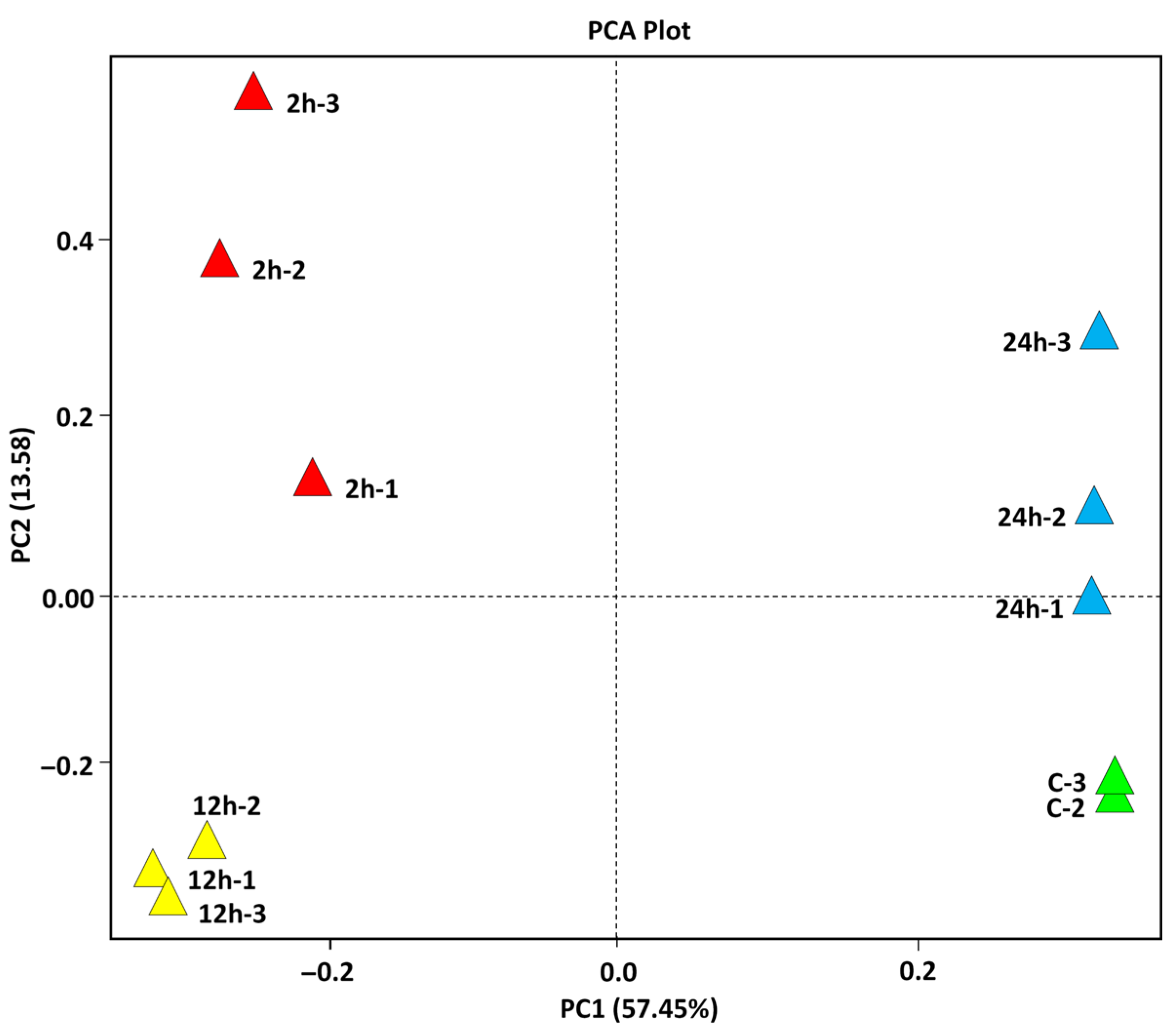

2.1. Quality Assessment, and Multi-Dimensional Validation of Salt-Stressed Wild Barley (Hordeum spontaneum) RNA-Seq Dataset

2.2. Temporal Dynamics of Gene Ontology (GO) Category Enrichment in Wild Barley Under Salt Stress

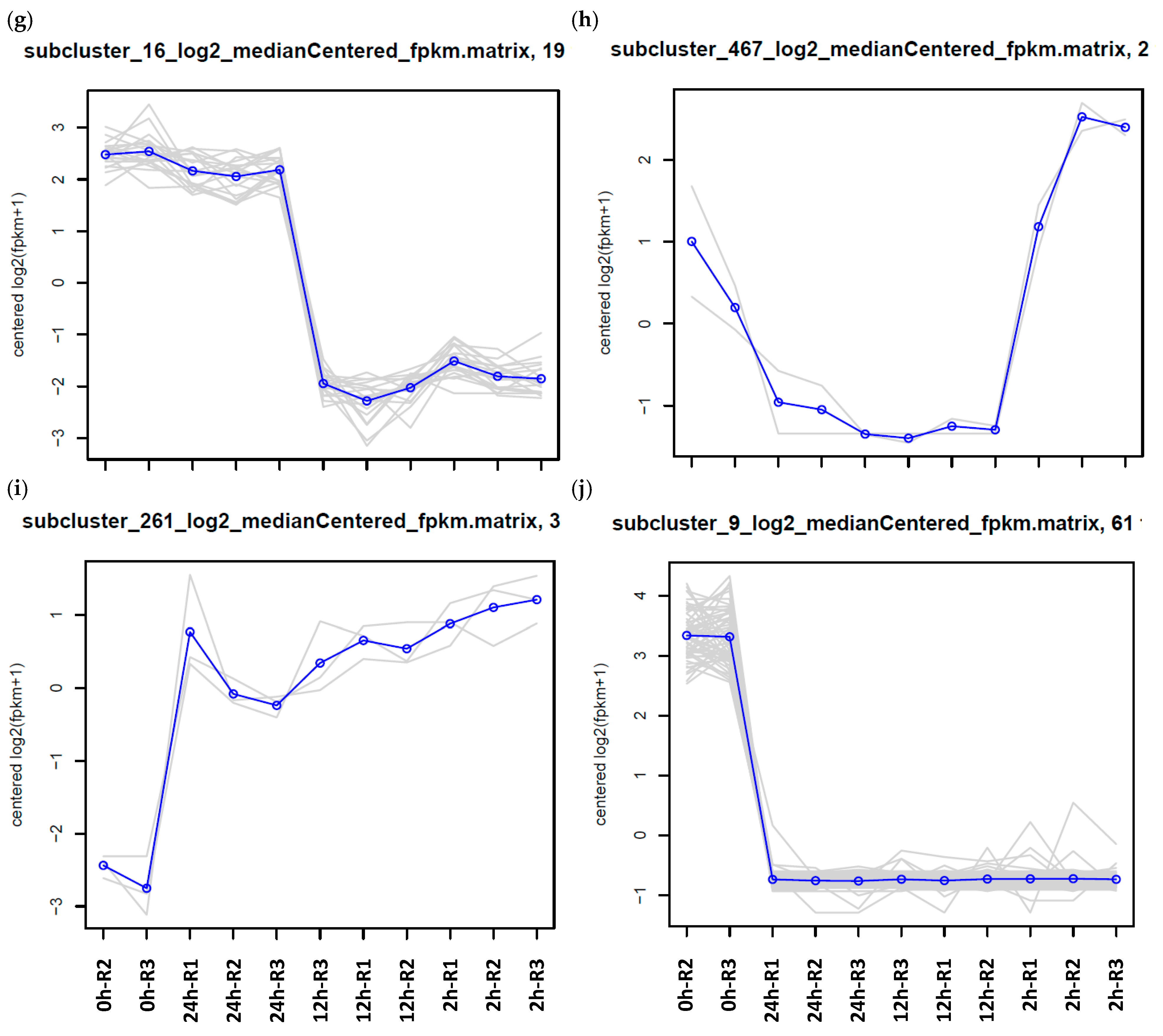

2.3. Temporal Transcriptional Dynamics and Metabolic Enrichment of KEGG Pathway Enzymes in Wild Barley Under Salt Stress

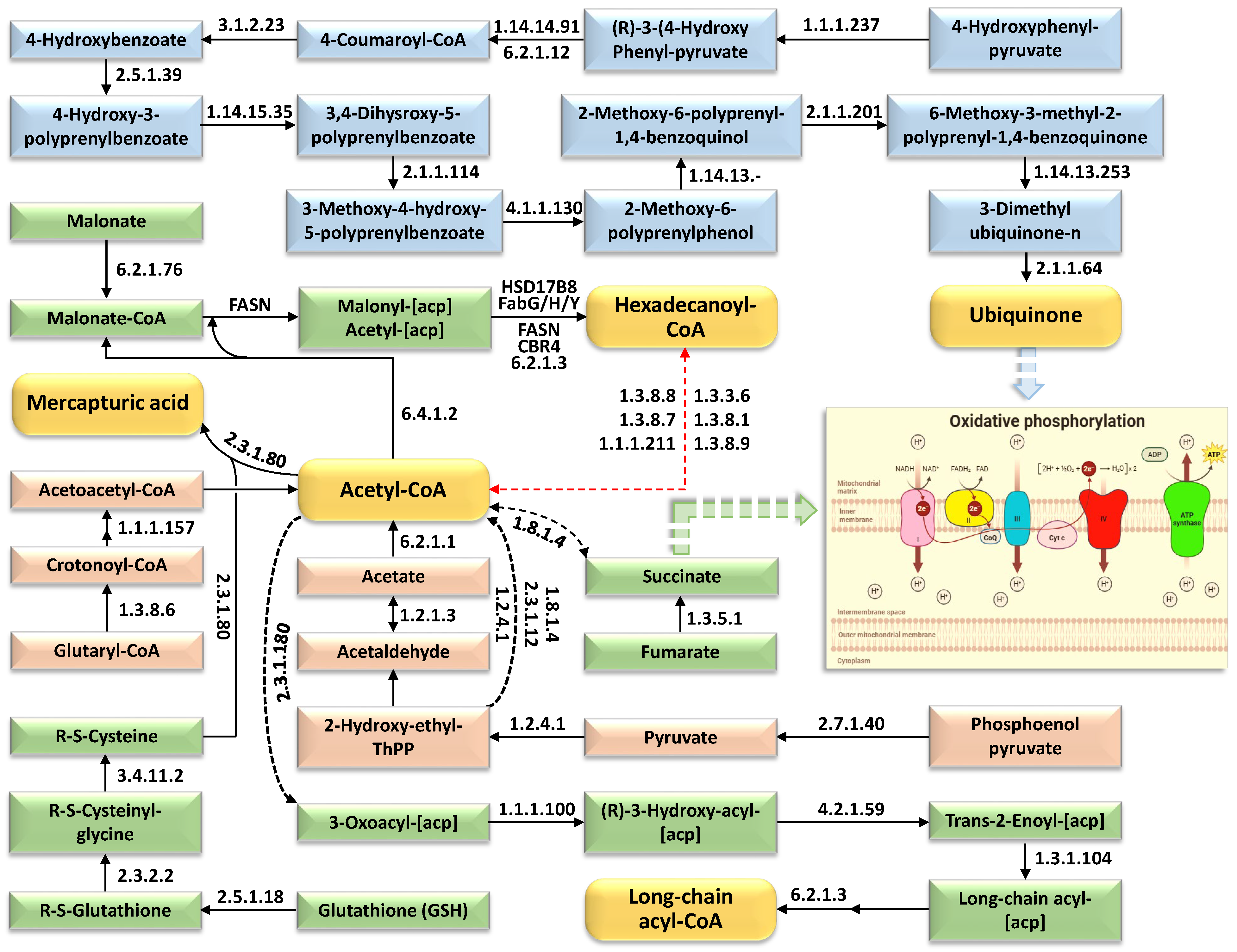

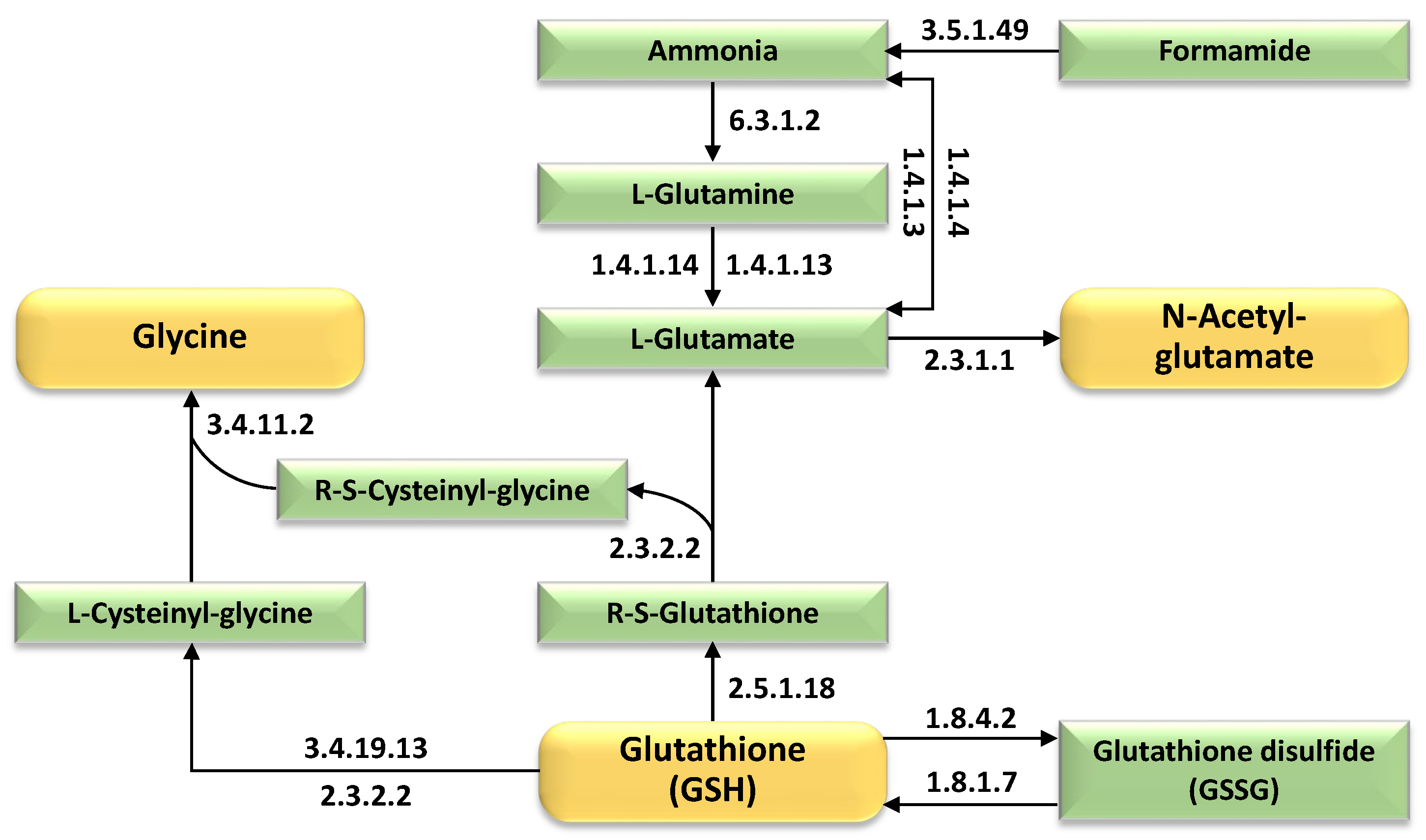

2.4. Integrated Metabolic Pathways and Adaptive Mechanisms Underpinning Salt Stress Tolerance in Wild Barley

2.5. Integrated GO-Based Overview of Differentially Expressed Genes

3. Discussion

3.1. Unlocking Salt Tolerance Mechanisms in H. spontaneum via OUH602 Genome-Guided Transcriptomic Profiling

3.2. Integrated Metabolic Network of Core Metabolites Underpinning Salt Stress Tolerance

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garthwaite, A.J.; von Bothmer, R.; Colmer, T.D. Salt tolerance in wild Hordeum species is associated with restricted entry of Na+ and Cl− into the shoots. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 2365–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, M.; Majidi, M.M.; Iravani, F.; Naderi, S.; Maibody, S. Enhancing salinity tolerance in barley: Harnessing introgressed nested genomes from the wild ancestor Hordeum spontaneum. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barqawi, A.A.; Abulfaraj, A.A. Salt Stress-Related Mechanisms in Leaves of the Wild Barley Hordeum spontaneum Generated from RNA-Seq Datasets. Life 2023, 13, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaghanipor, N.; Arzani, A.; Rahimmalek, M.; Ravash, R. Physiological and Transcriptome Indicators of Salt Tolerance in Wild and Cultivated Barley. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 819282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vysotskaya, L.; Hedley, P.E.; Sharipova, G.; Veselov, D.; Kudoyarova, G.; Morris, J.; Jones, H.G. Effect of salinity on water relations of wild barley plants differing in salt tolerance. AoB Plants 2010, 2010, plq006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sh, S.; Yusupgulyev, H.; Tahyrowa, O. On the Origin and Domestication History of Barley (Hordeum vulgare). Вестник науки 2023, 1, 1067–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Turuspekov, Y.; Abugalieva, S.; Ermekbayev, K.; Sato, K. Genetic characterization of wild barley populations (Hordeum vulgare ssp. spontaneum) from Kazakhstan based on genome wide SNP analysis. Breed. Sci. 2014, 64, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn, C.P.; Heersche, I.; Van Berkel, Y.E.; Nevo, E.; Lambers, H.; Poorter, H. Growth characteristics in Hordeum spontaneum populations from different habitats. New Phytol. 2000, 146, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, A.; Muller, K.; Schafer-Pregl, R.; El Rabey, H.; Effgen, S.; Ibrahim, H.H.; Pozzi, C.; Rohde, W.; Salamini, F. On the origin and domestication history of Barley (Hordeum vulgare). Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovesna, J.; Chrpova, J.; Kolarikova, L.; Svoboda, P.; Hanzalova, A.; Palicova, J.; Holubec, V. Exploring wild Hordeum spontaneum and Hordeum marinum accessions as genetic resources for fungal resistance. Plants 2023, 12, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulfaraj, A.A. Stepwise signal transduction cascades under salt stress in leaves of wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum). Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2020, 34, 860–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Jing, W.; Cao, C.; Sun, M.; Chi, W.; Zhao, S.; Dai, J.; Shi, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, B.; et al. Transcriptional repressor RST1 controls salt tolerance and grain yield in rice by regulating gene expression of asparagine synthetase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2210338119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athar, H.U.; Zulfiqar, F.; Moosa, A.; Ashraf, M.; Zafar, Z.U.; Zhang, L.; Ahmed, N.; Kalaji, H.M.; Nafees, M.; Hossain, M.A.; et al. Salt stress proteins in plants: An overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 999058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

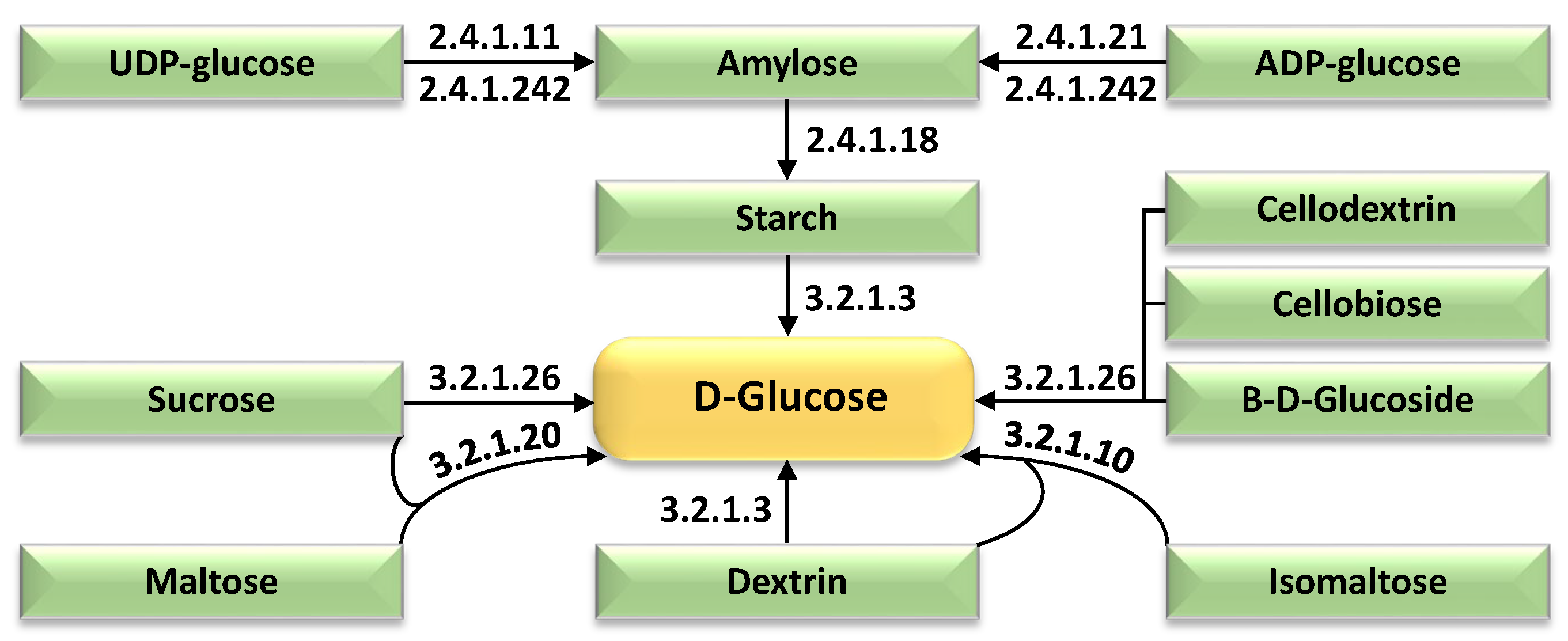

- Abuslima, E.; Kanbar, A.; Ismail, A.; Raorane, M.L.; Eiche, E.; El-Sharkawy, I.; Junker, B.H.; Riemann, M.; Nick, P. Salt stress-induced remodeling of sugar transport: A role for promoter alleles of SWEET13. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nveawiah-Yoho, P.; Zhou, J.; Palmer, M.; Sauve, R.; Zhou, S.; Howe, K.J.; Fish, T.; Thannhauser, T.W. Identification of proteins for salt tolerance using a comparative proteomics analysis of tomato accessions with contrasting salt tolerance. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2013, 138, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, G.; Lv, C.; Stevanato, P.; Li, R.; Liu, H.; Yu, L.; Wang, Y. Transcriptome analysis of salt-sensitive and tolerant genotypes reveals salt-tolerance metabolic pathways in sugar beet. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.R. Salinity Tolerance and Transcriptomics in Rice; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

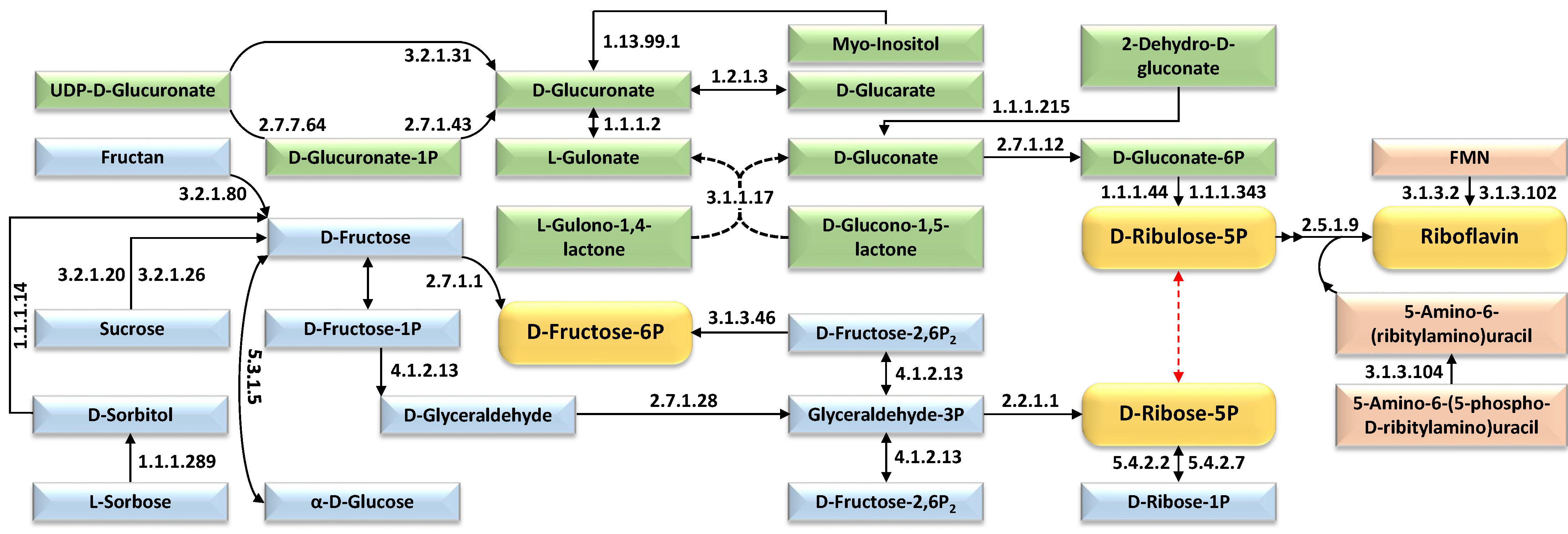

- Alfarouk, K.O.; Ahmed, S.B.; Elliott, R.L.; Benoit, A.; Alqahtani, S.S.; Ibrahim, M.E.; Bashir, A.H.; Alhoufie, S.T.; Elhassan, G.O.; Wales, C.C. The pentose phosphate pathway dynamics in cancer and its dependency on intracellular pH. Metabolites 2020, 10, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data, Version 0.10; Babraham Bioinformatics, Babraham Institute: Cambridge, UK, 2010; Volume 1.

- Chen, G.; Mishina, K.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Tagiri, A.; Kikuchi, S.; Sassa, H.; Oono, Y.; Komatsuda, T. Organ-enriched gene expression during floral morphogenesis in wild barley. Plant J. 2023, 116, 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Mascher, M.; Himmelbach, A.; Haberer, G.; Spannagl, M.; Stein, N. Chromosome-scale assembly of wild barley accession “OUH602”. G3: Genes, Genomes. Genetics 2021, 11, jkab244. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, S.; Whitehead, L.; Larson, T.R.; Graham, I.A.; Rodriguez, P.L. The coenzyme a biosynthetic enzyme phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase plays a crucial role in plant growth, salt/osmotic stress resistance, and seed lipid storage. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Deng, C.; Wang, S.; Deng, Q.; Chu, Y.; Bai, Z.; Huang, A.; Zhang, Q.; He, Q. The RNA landscape of Dunaliella salina in response to short-term salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1278954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Liu, L.; Rupasinghe, T.W.T.; Roessner, U.; Barkla, B.J. Salt stress alters membrane lipid content and lipid biosynthesis pathways in the plasma membrane and tonoplast. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 805–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egea, I.; Estrada, Y.; Faura, C.; Egea-Fernández, J.M.; Bolarin, M.C.; Flores, F.B. Salt-tolerant alternative crops as sources of quality food to mitigate the negative impact of salinity on agricultural production. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1092885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, Z.; Miao, X. Lipid Droplets Mediate Salt Stress Tolerance in Parachlorella kessleri. Plant Physiol. 2019, 181, 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandehagh, A.; Taylor, N.L. Can alternative metabolic pathways and shunts overcome salinity induced inhibition of central carbon metabolism in crops? Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.I.; Jalil, S.U.; Ansari, S.A.; Hasanuzzaman, M. GABA shunt: A key-player in mitigation of ROS during stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 94, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, D.; Suh, M.C. Cuticle ultrastructure, cuticular lipid composition, and gene expression in hypoxia-stressed Arabidopsis stems and leaves. Plant Cell Rep. 2017, 36, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, M.F.; Lung, S.C.; Guo, Z.H.; Chye, M.L. Roles of acyl-CoA-binding proteins in plant reproduction. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2918–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.-H.; Chye, M.-L. Plant acyl-CoA-binding proteins—Their lipid and protein interactors in abiotic and biotic stresses. Cells 2021, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Pei, L.; Liu, J.; Xia, X.; Che, R.; Li, H. Molecular characterization, expression and functional analysis of acyl-CoA-binding protein gene family in maize (Zea mays). BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. Characterization of Acyl coenzyme a Binding Protein 4 in Rice. Master’s Thesis, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.-H.; Pogancev, G.; Meng, W.; Du, Z.-Y.; Liao, P.; Zhang, R.; Chye, M.-L. The overexpression of rice ACYL-COA-BINDING PROTEIN4 improves salinity tolerance in transgenic rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 183, 104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Ma, M.; Gu, M.; Li, S.; Li, M.; Guo, G.; Xing, G. Acyl-CoA-binding protein (ACBP) genes involvement in response to abiotic stress and exogenous hormone application in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Cai, S.; Chen, M.; Ye, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Dai, F.; Wu, F.; Zhang, G. Tissue metabolic responses to salt stress in wild and cultivated barley. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, Z.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, C.; Yao, X.; Yang, Y.; Cai, X. Molecular Cloning and Analysis of an Acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase Gene (EkAACT) from Euphorbia kansui Liou. Plants 2022, 11, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

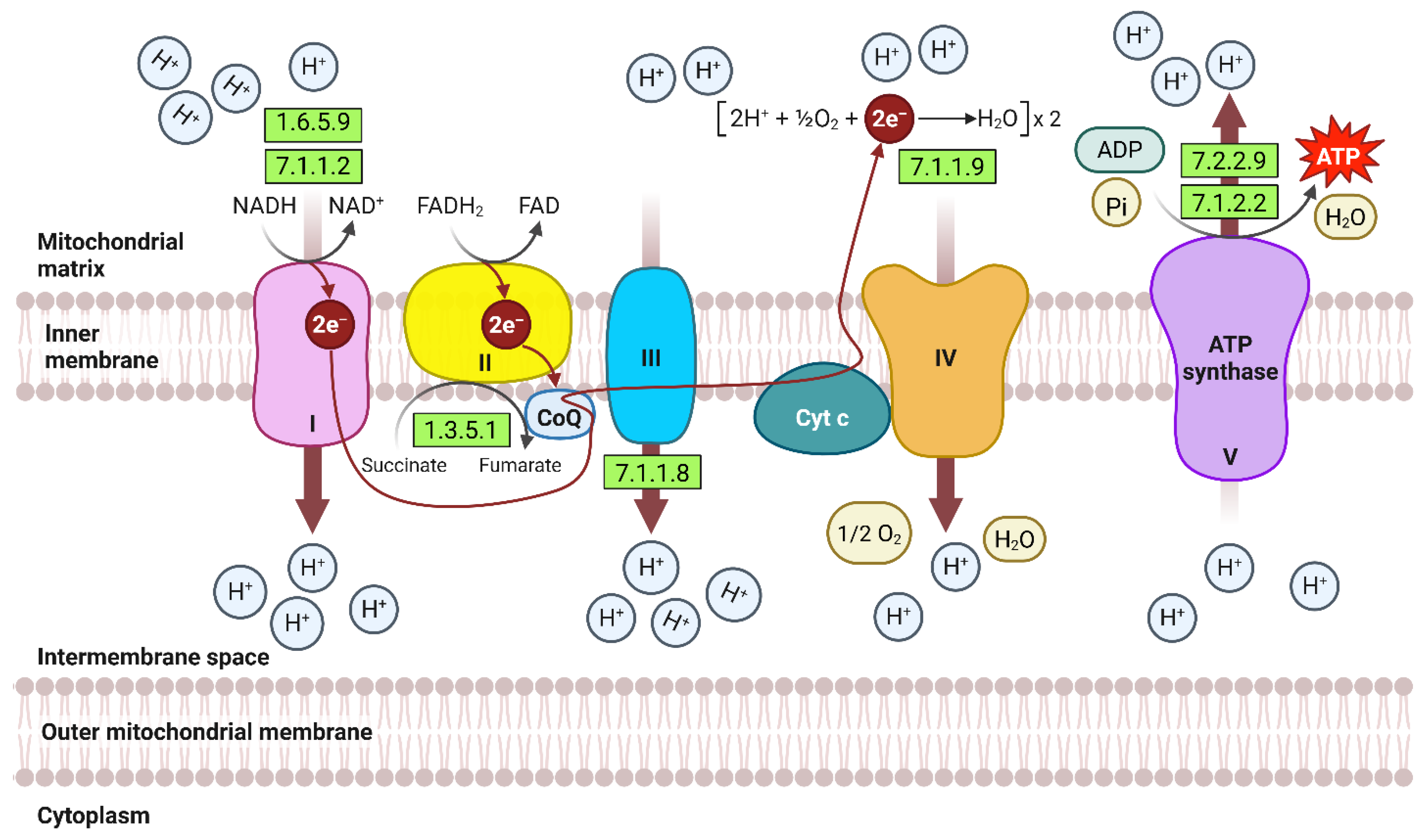

- Dourmap, C.; Roque, S.; Morin, A.; Caubriere, D.; Kerdiles, M.; Beguin, K.; Perdoux, R.; Reynoud, N.; Bourdet, L.; Audebert, P.A.; et al. Stress signalling dynamics of the mitochondrial electron transport chain and oxidative phosphorylation system in higher plants. Ann. Bot. 2020, 125, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che-Othman, M.H.; Millar, A.H.; Taylor, N.L. Connecting salt stress signalling pathways with salinity-induced changes in mitochondrial metabolic processes in C 3 plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 2875–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, F.; Lin, H.; Guo, Y. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J. Genet. Genom. 2024, 51, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che-Othman, M.H.; Jacoby, R.P.; Millar, A.H.; Taylor, N.L. Wheat mitochondrial respiration shifts from the tricarboxylic acid cycle to the GABA shunt under salt stress. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1166–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fal, S.; Aasfar, A.; Rabie, R.; Smouni, A.; Arroussi, H.E. Salt induced oxidative stress alters physiological, biochemical and metabolomic responses of green microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, T.; Shen, G.; Esmaeili, N.; Zhang, H. Plants’ response mechanisms to salinity stress. Plants 2023, 12, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierbach, A.; Groh, K.J.; Schoenenberger, R.; Schirmer, K.; Suter, M.J. Characterization of the Mercapturic Acid Pathway, an Important Phase II Biotransformation Route, in a Zebrafish Embryo Cell Line. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 2863–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, P.E.; Anders, M.W. The mercapturic acid pathway. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2019, 49, 819–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Zhou, H. Plant salt response: Perception, signaling, and tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1053699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, L.M.; Killiny, N.; Holden, P.; Gmitter, F.G., Jr.; Grosser, J.W.; Dutt, M. Physiological and biochemical evaluation of salt stress tolerance in a citrus tetraploid somatic hybrid. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Kosma, D.K.; Lu, S. Functional Role of Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Synthetases in Plant Development and Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 640996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, R.; Ejsing, C.S.; Antonny, B. Homeoviscous Adaptation and the Regulation of Membrane Lipids. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 4776–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, Z.H. Molecular and Evolutionary Mechanisms of Cuticular Wax for Plant Drought Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jiang, X.; Yuan, Z. Plant Responses and Adaptations to Salt Stress: A Review. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Recent advances in cuticular wax biosynthesis and its regulation in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sackey, O.K.; Feng, N.; Mohammed, Y.Z.; Dzou, C.F.; Zheng, D.; Zhao, L.; Shen, X. A comprehensive review on rice responses and tolerance to salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1561280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, D.; Han, X.; Wei, R.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Gong, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Coenzyme Q GhCoQ9 enhanced the salt resistance by preserving the homeostasis of mitochondrial in upland cotton. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 224, 109909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, K.G.; Liu, Q.; Xu, X.; Manz, C.; Purper, S.; Eghbalian, R.; Munch, S.W.; Wehl, I.; Brase, S.; Eiche, E.; et al. A mitochondria-targeted coenzyme Q peptoid induces superoxide dismutase and alleviates salinity stress in plant cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Day, D.A.; Fricke, W.; Watt, M.; Arsova, B.; Barkla, B.J.; Bose, J.; Byrt, C.S.; Chen, Z.H.; Foster, K.J.; et al. Energy costs of salt tolerance in crop plants. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1072–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lu, S. Plastoquinone and Ubiquinone in Plants: Biosynthesis, Physiological Function and Metabolic Engineering. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, L.; Xie, X.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, F.; Wu, S.; Li, M.; Gao, S.; Gu, W.; Wang, G. Positive correlation between PSI response and oxidative pentose phosphate pathway activity during salt stress in an intertidal macroalga. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, N.; Perveen, S. Riboflavin (vitamin B2) priming modulates growth, physiological and biochemical traits of maize (Zea mays L.) under salt stress. Pak. J. Bot. 2024, 56, 1209–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiadkong, K.; Fauzia, A.N.; Yamaguchi, N.; Ueda, A. Exogenous riboflavin (vitamin B2) application enhances salinity tolerance through the activation of its biosynthesis in rice seedlings under salinity stress. Plant Sci. 2024, 339, 111929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olfat, N.; Ashoori, M.; Saedisomeolia, A. Riboflavin is an antioxidant: A review update. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1887–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramaniam, S.; Yaplito-Lee, J. Riboflavin metabolism: Role in mitochondrial function. J. Transl. Genet. Genom. 2020, 4, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, M.; Nassar, R.; Abdel-Aziz, N.G.; Abdel-Aal, A.S. Riboflavin minimizes the deleterious effects of salinity stress on growth, chloroplast pigments, free proline, activity of antioxidant enzyme catalase and leaf anatomy of Tecoma capensis (Thumb.) Lindl. Middle East. J. Agric. 2017, 6, 757–765. [Google Scholar]

- Revuelta, J.L.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Lozano-Martinez, P.; Diaz-Fernandez, D.; Buey, R.M.; Jimenez, A. Bioproduction of riboflavin: A bright yellow history. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L. New Findings on the Role of Gnd1, Rib6, Rfe1 and Some Other Genes on Riboflavin Oversynthesis of the Yeast Candida Famata; National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pompelli, M.F.; Ferreira, P.P.B.; Chaves, A.R.M.; Figueiredo, R.; Martins, A.O.; Jarma-Orozco, A.; Bhatt, A.; Batista-Silva, W.; Endres, L.; Araujo, W.L. Physiological, metabolic, and stomatal adjustments in response to salt stress in Jatropha curcas. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 168, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomchalothorn, T.; Maneeprasobsuk, S.; Bangyeekhun, E.; Boon-Long, P.; Chadchawan, S. The role of the bifunctional enzyme, fructose-6-phosphate-2-kinase/fructose-2, 6-bisphosphatase, in carbon partitioning during salt stress and salt tolerance in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Sci. 2009, 176, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.K.; Kumar, M.; Li, W.; Luo, Y.; Burritt, D.J.; Alkan, N.; Tran, L.P. Enhancing Salt Tolerance of Plants: From Metabolic Reprogramming to Exogenous Chemical Treatments and Molecular Approaches. Cells 2020, 9, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.; Cho, M.-H.; Bhoo, S.H.; Hahn, T.-R. Pyrophosphate: Fructose-6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase is involved in the tolerance of Arabidopsis seedlings to salt and osmotic stresses. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2014, 50, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. A review on plant responses to salt stress and their mechanisms of salt resistance. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xie, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yao, Y.; Wang, C.; Niu, T.; Bakpa, E.P. Trehalose alleviates salt tolerance by improving photosynthetic performance and maintaining mineral ion homeostasis in tomato plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 974507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellami, S.; Le Hir, R.; Thorpe, M.R.; Vilaine, F.; Wolff, N.; Brini, F.; Dinant, S. Salinity Effects on Sugar Homeostasis and Vascular Anatomy in the Stem of the Arabidopsis Thaliana Inflorescence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, G.; Wei, S.; Li, L.; Zuo, S.; Liu, X.; Gu, W.; Li, J. Effects of exogenous glucose and sucrose on photosynthesis in triticale seedlings under salt stress. Photosynthetica 2019, 57, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Geng, G.; Wang, Y. Salt Tolerance in Sugar Beet: From Impact Analysis to Adaptive Mechanisms and Future Research. Plants 2024, 13, 3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atta, K.; Mondal, S.; Gorai, S.; Singh, A.P.; Kumari, A.; Ghosh, T.; Roy, A.; Hembram, S.; Gaikwad, D.J.; Mondal, S. Impacts of salinity stress on crop plants: Improving salt tolerance through genetic and molecular dissection. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1241736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangola, M.P.; Ramadoss, B.R. Sugars play a critical role in abiotic stress tolerance in plants. In Biochemical, Physiological and Molecular Avenues for Combating Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Yang, Y. How plants tolerate salt stress. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 5914–5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

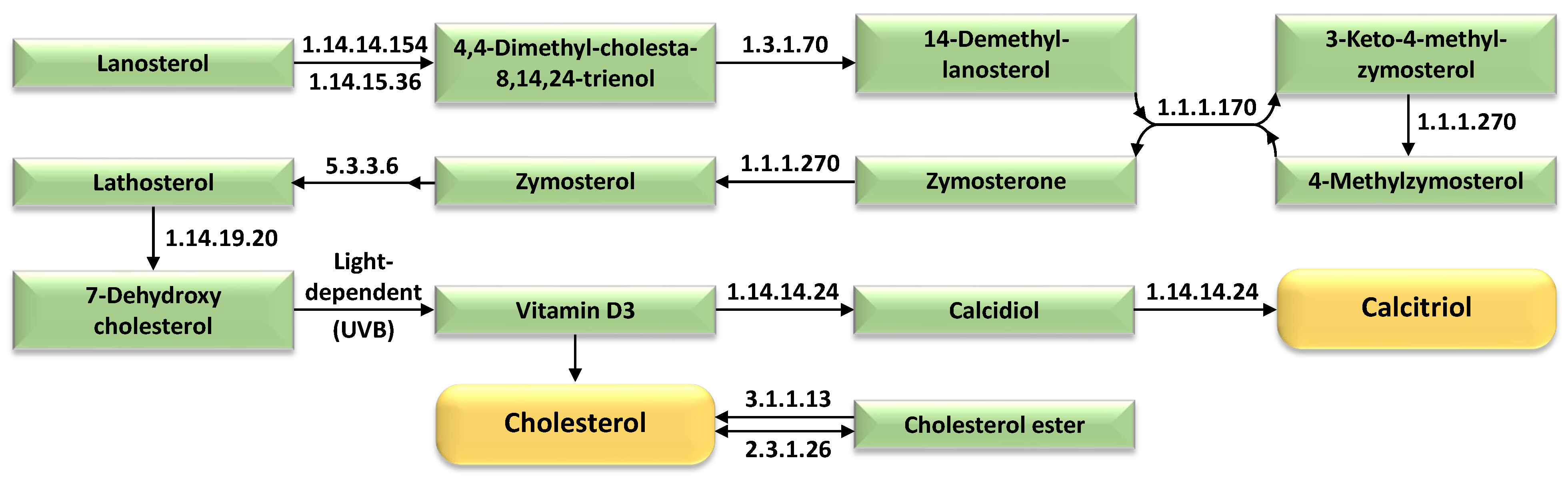

- Du, Y.; Fu, X.; Chu, Y.; Wu, P.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; Tian, H.; Zhu, B. Biosynthesis and the Roles of Plant Sterols in Development and Stress Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Liu, L.; Barkla, B.J. Membrane Lipid Remodeling in Response to Salinity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valitova, J.; Renkova, A.; Beckett, R.; Minibayeva, F. Stigmasterol: An Enigmatic Plant Stress Sterol with Versatile Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Feng, L.; Liu, Y.; Liao, W. Mitogen-activated protein kinase is involved in salt stress response in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) seedlings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.A.; Zeeshan Ul Haq, M.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Mushtaq, N.; Tahir, H.; Wang, Z. Transcriptomic insights into salt stress response in two pepper species: The role of MAPK and plant hormone signaling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifikalhor, M.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Shomali, A.; Azad, N.; Hassani, B.; Lastochkina, O.; Li, T. Calcium signaling and salt tolerance are diversely entwined in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2019, 14, 1665455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Xiao, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Bao, X.; Xing, K.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, S. Calcitriol ameliorates damage in high-salt diet-induced hypertension: Evidence of communication with the gut–kidney axis. Exp. Biol. Med. 2022, 247, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poladian, N.; Navasardyan, I.; Narinyan, W.; Orujyan, D.; Venketaraman, V. Potential Role of Glutathione Antioxidant Pathways in the Pathophysiology and Adjunct Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders. Clin. Pract. 2023, 13, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, B. Glutathione: The master antioxidant. Ozone Ther. Glob. J. 2023, 13, 175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Averill-Bates, D.A. The antioxidant glutathione. In Vitamins and Hormones; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 121, pp. 109–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Plant responses and tolerance to salt stress: Physiological and molecular interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Anee, T.I.; Fujita, M. Glutathione in plants: Biosynthesis and physiological role in environmental stress tolerance. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2017, 23, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, Y.S.; Wong, S.K.; Ismail, N.H.; Zengin, G.; Duangjai, A.; Saokaew, S.; Phisalprapa, P.; Tan, K.W.; Goh, B.H.; Tang, S.Y. Mitigation of Environmental Stress-Impacts in Plants: Role of Sole and Combinatory Exogenous Application of Glutathione. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 791205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofy, M.R.; Elhawat, N.; Tarek, A. Glycine betaine counters salinity stress by maintaining high K(+)/Na(+) ratio and antioxidant defense via limiting Na(+) uptake in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 200, 110732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z. Glycine betaine increases salt tolerance in maize (Zea mays L.) by regulating Na+ homeostasis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 978304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Han, G.; Sun, X.; Sheng, Y.; Yan, J.; Scheller, H.V.; Zhang, A. Over-Expression of a Maize N-Acetylglutamate Kinase Gene (ZmNAGK) Improves Drought Tolerance in Tobacco. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Liu, M.; Chu, N.; Chen, G.; Wang, P.; Mo, J.; Guo, H.; Xu, J.; Zhou, H. Combined transcriptome and metabolome reveal glutathione metabolism plays a critical role in resistance to salinity in rice landraces HD961. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 952595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhou, C.; Feng, N.; Zheng, D.; Shen, X.; Rao, G.; Huang, Y.; Cai, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, R. Transcriptomic and lipidomic analysis reveals complex regulation mechanisms underlying rice roots’ response to salt stress. Metabolites 2024, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, G.; Wang, F.; Zhao, L.; Liu, N.; Abudurezike, A.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Shi, S. Salt-responsive transcriptome analysis of triticale reveals candidate genes involved in the key metabolic pathway in response to salt stress. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, M.M.; Goyal, E.; Singh, A.K.; Gaikwad, K.; Kanika, K. Shedding light on response of Triticum aestivum cv. Kharchia Local roots to long-term salinity stress through transcriptome profiling. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 90, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, E.; Amit, S.K.; Singh, R.S.; Mahato, A.K.; Chand, S.; Kanika, K. Transcriptome profiling of the salt-stress response in Triticum aestivum cv. Kharchia Local. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefirad, S.; Soltanloo, H.; Ramezanpour, S.S.; Zaynali Nezhad, K.; Shariati, V. The RNA-seq transcriptomic analysis reveals genes mediating salt tolerance through rapid triggering of ion transporters in a mutant barley. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Fu, L.; Dai, F.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, G.; Wu, D. Multi-omics analysis reveals molecular mechanisms of shoot adaption to salt stress in Tibetan wild barley. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahieldin, A.; Atef, A.; Sabir, J.S.; Gadalla, N.O.; Edris, S.; Alzohairy, A.M.; Radhwan, N.A.; Baeshen, M.N.; Ramadan, A.M.; Eissa, H.F.; et al. RNA-Seq analysis of the wild barley (H. spontaneum) leaf transcriptome under salt stress. C R. Biol. 2015, 338, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.; Dokel, S.; Amstislavskiy, V.; Wuttig, D.; Sultmann, H.; Lehrach, H.; Yaspo, M.L. A simple strand-specific RNA-Seq library preparation protocol combining the Illumina TruSeq RNA and the dUTP methods. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 422, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, H. Library preparation and mRNA sequencing (Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA with Ribo-Zero Globin). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 300, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, B.J.; Papanicolaou, A.; Yassour, M.; Grabherr, M.; Blood, P.D.; Bowden, J.; Couger, M.B.; Eccles, D.; Li, B.; Lieber, M.; et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 1494–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simao, F.A.; Waterhouse, R.M.; Ioannidis, P.; Kriventseva, E.V.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3210–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q. Trinity: Reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Lun, A.T.; Smyth, G.K. From reads to genes to pathways: Differential expression analysis of RNA-Seq experiments using Rsubread and the edgeR quasi-likelihood pipeline. F1000Research 2016, 5, 1438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

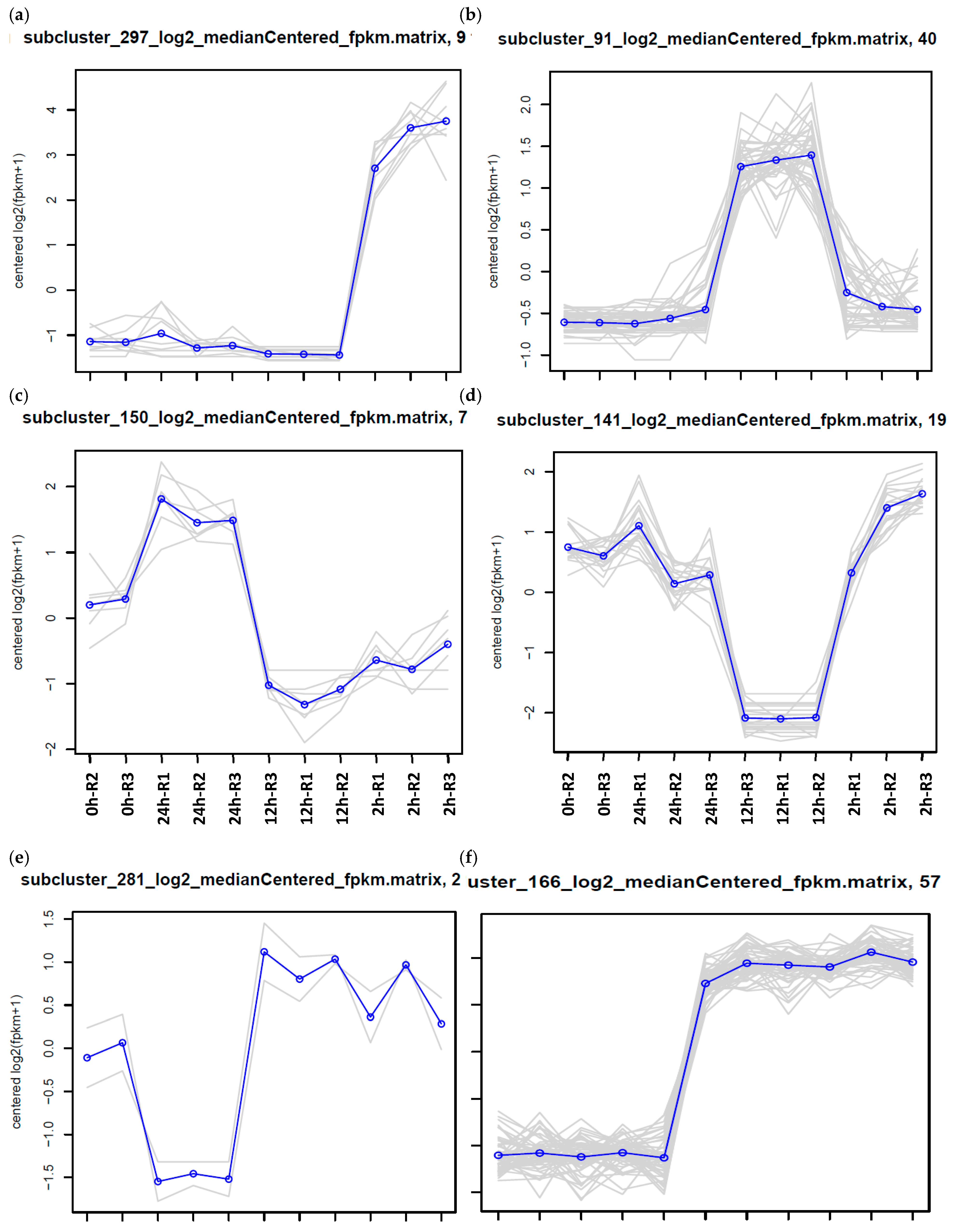

| Expression Group | Cluster No. | |

|---|---|---|

| a | 2 h up | 119, 11, 211, 230, 270, 297, 326, 534, 600, 95 |

| b | 12 h up | 129, 19, 209, 258, 284, 478, 505, 516, 526, 61, 91, 92 |

| c | 24 h up | 148, 150, 233, 290, 291, 357, 502, 509, 575 |

| 2 h down | NA | |

| d | 12 h down | 121, 132, 136, 141, 147, 158, 169, 176, 178, 210, 237, 253, 267, 272, 283, 286, 315, 33, 351, 355, 379, 37, 395, 427, 428, 44, 474, 488, 506, 539, 550, 56, 583, 584 |

| e | 24 h down | 146, 274, 281, 306, 327, 356, 399 |

| f | 2 h/12 h up | 101, 102, 103, 106, 117, 125, 127, 128, 130, 144, 145, 151, 15, 160, 166, 180, 186, 18, 193, 201, 20, 225, 229, 238, 239, 240, 244, 247, 24, 259, 264, 268, 269, 276, 278, 27, 311, 319, 320, 323, 34, 361, 362, 367, 374, 389, 399, 40, 429, 454, 457, 508, 541, 542, 59, 79, 88, 90, 94 |

| g | 2 h/12 h down | 109, 10, 110, 118, 124, 149, 14, 16, 172, 195, 231, 234, 235, 248, 26, 271, 285, 300, 30, 32, 372, 3, 415, 416, 446, 455, 490, 495, 511, 81, 83, 8 |

| 12 h/24 h up | NA | |

| h | 12 h/24 h down | 204, 467 |

| i | 2 h/12 h/24 h up | 164, 222, 261, 279, 397, 528 |

| j | 2 h/12 h/24 h down | 111, 165, 194, 1, 212, 317, 377, 387, 421, 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abulfaraj, A.A.; Baz, L. Temporal Dynamics of Gene Expression and Metabolic Rewiring in Wild Barley (Hordeum spontaneum) Under Salt Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010358

Abulfaraj AA, Baz L. Temporal Dynamics of Gene Expression and Metabolic Rewiring in Wild Barley (Hordeum spontaneum) Under Salt Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010358

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbulfaraj, Aala A., and Lina Baz. 2026. "Temporal Dynamics of Gene Expression and Metabolic Rewiring in Wild Barley (Hordeum spontaneum) Under Salt Stress" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010358

APA StyleAbulfaraj, A. A., & Baz, L. (2026). Temporal Dynamics of Gene Expression and Metabolic Rewiring in Wild Barley (Hordeum spontaneum) Under Salt Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010358