Visualizing the Functional Dynamics of P-Glycoprotein and Its Modulation by Elacridar via High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

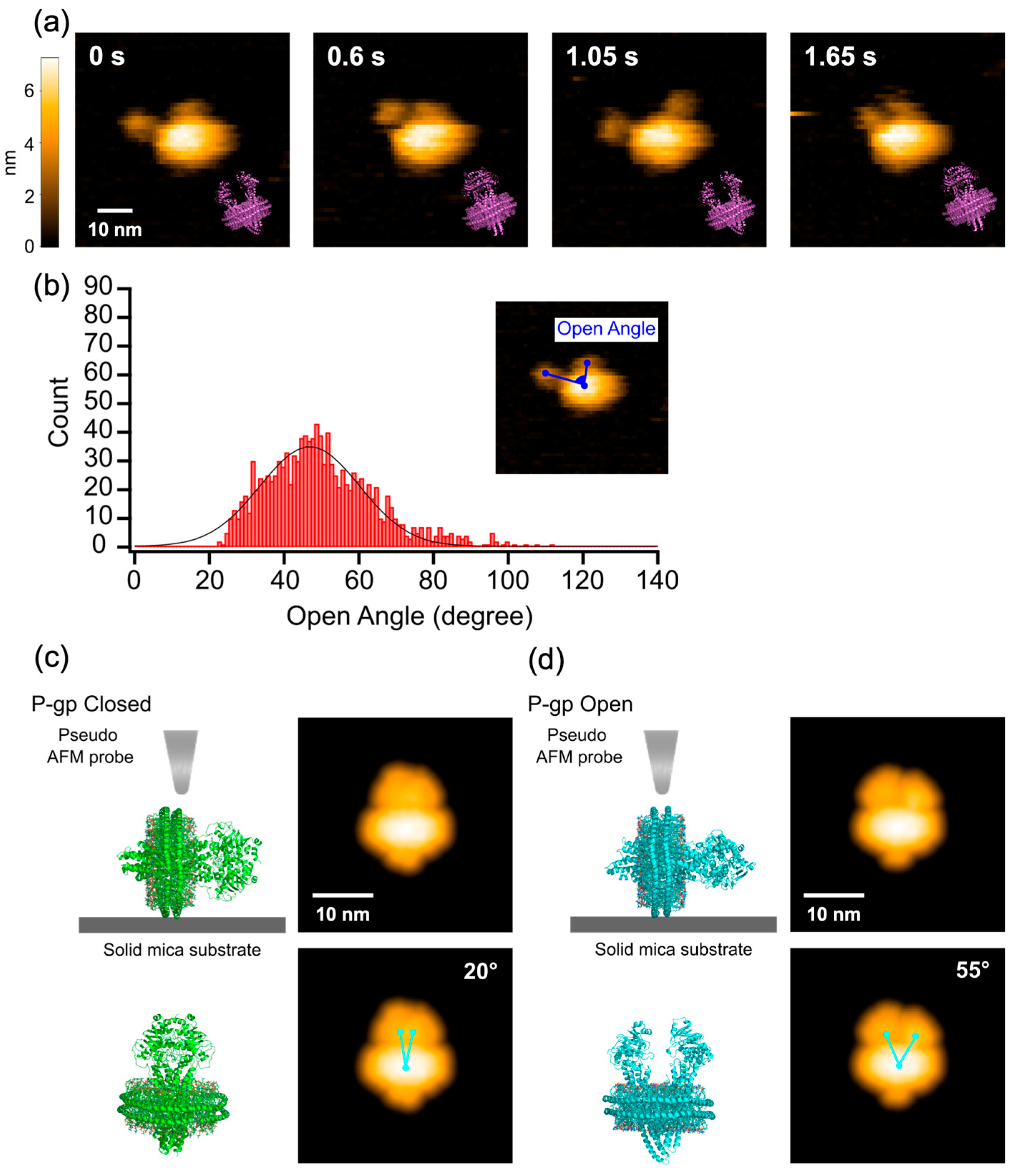

2.1. HS-AFM Observation of Nanodisc-Reconstituted P-gp in the Apo State

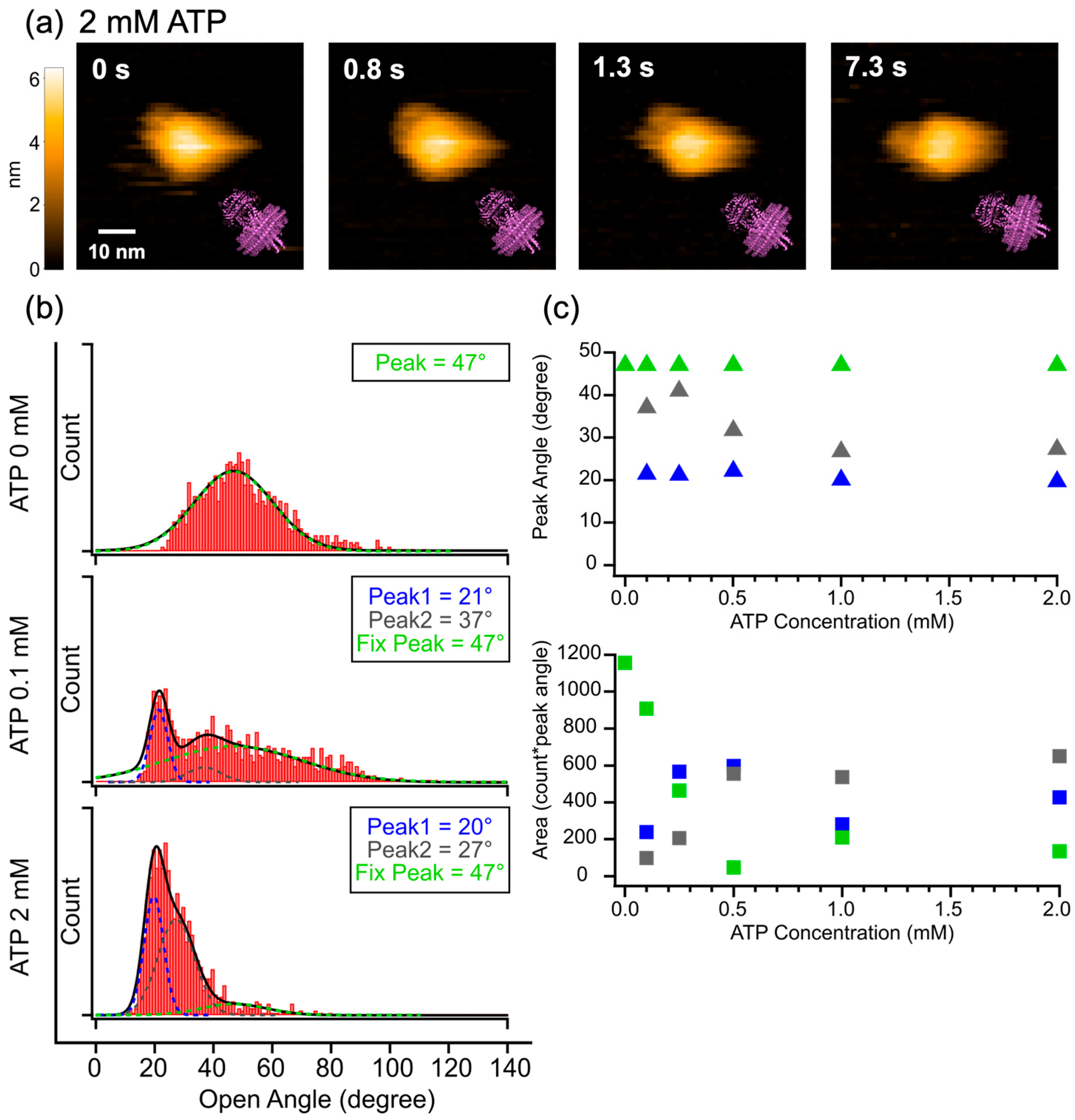

2.2. HS-AFM Observation of Nanodisc-Reconstituted P-gp in the Presence of ATP

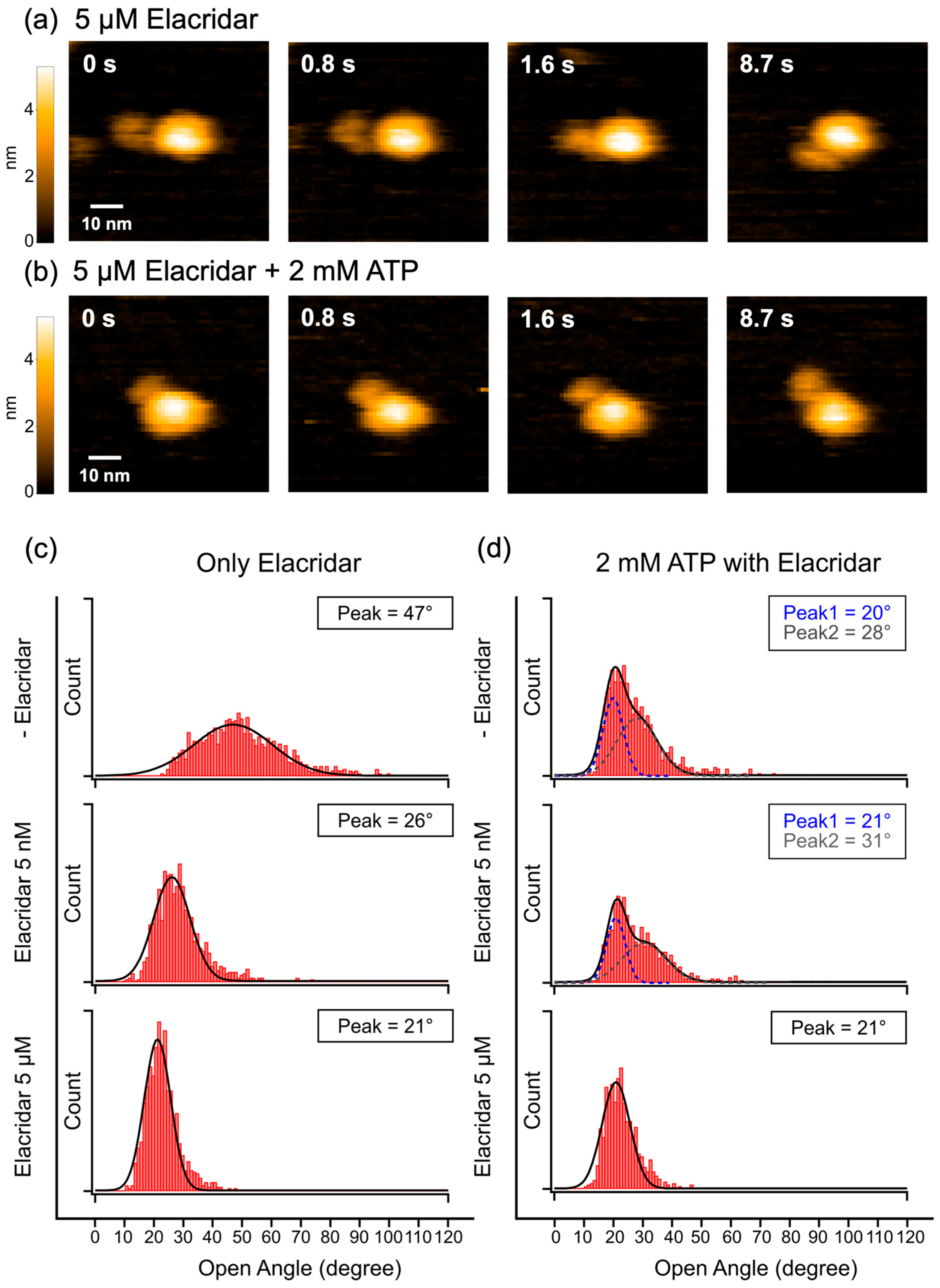

2.3. HS-AFM Observation of Nanodisc-Reconstituted P-gp with the Inhibitor Elacridar

3. Discussion

3.1. Dynamics of P-gp-ND in the Nucleotide-Free Apo State

3.2. Further Performance for Dynamics of P-gp-ND in the Presence of ATP

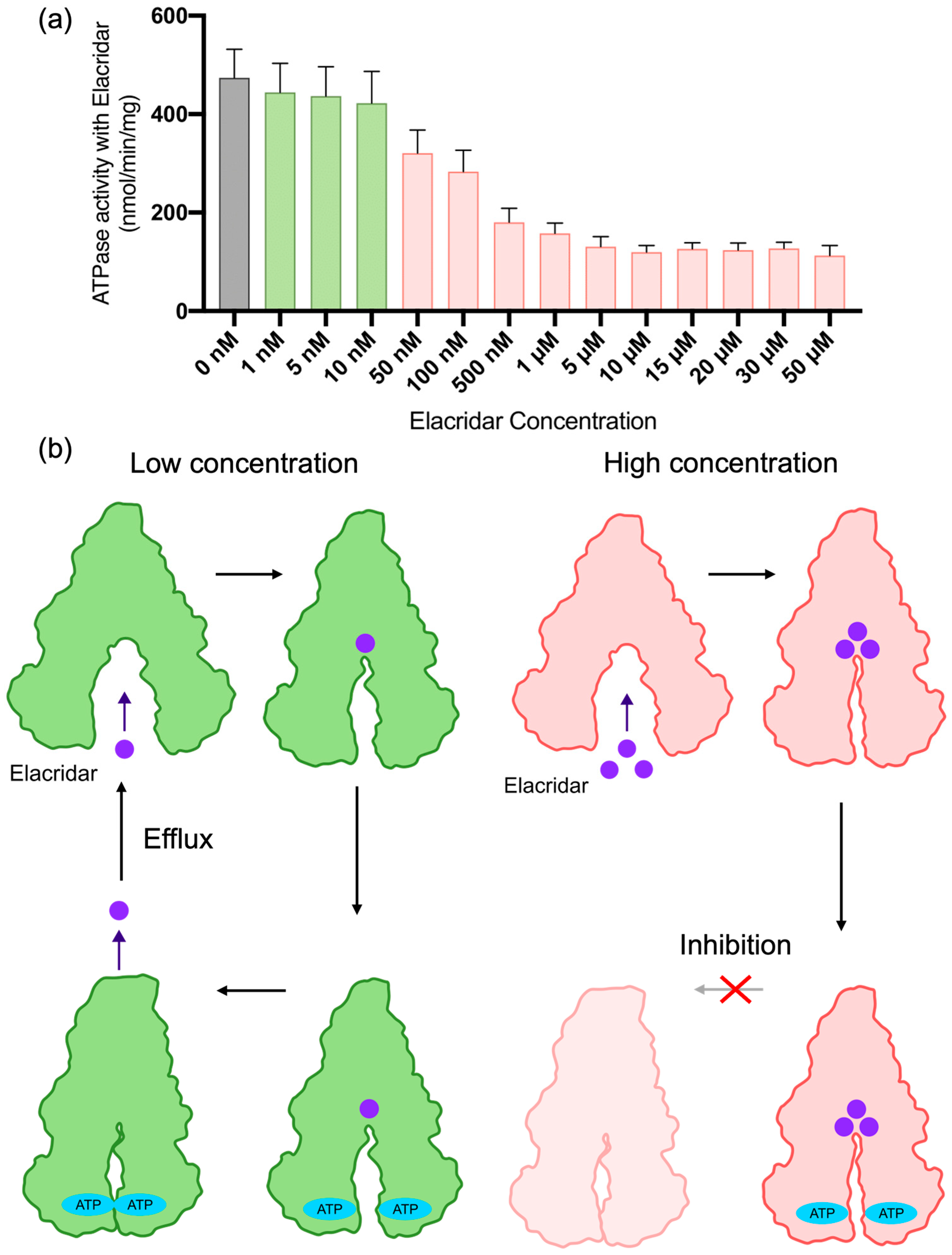

3.3. Relationship Between P-gp Inhibition, Dynamics, and Activity

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Purification of P-gp-ND

4.2. Measurement of ATPase Activity

4.3. Cryo-EM Sample Preparation and Data Collection

4.4. EM Data Processing

4.5. Sample Preparation for HS-AFM Observation

4.6. HS-AFM Observation and Instruments

4.7. Image Processing and Data Analysis of HS-AFM Data

4.8. Generation of Simulated AFM Images

4.9. Embedding and Modeling of Known Structures into Nanodiscs

4.10. Dynamics Simulation Using Normal Mode Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| P-gp | P-glycoprotein |

| P-gp-ND | P-glycoprotein reconstituted into a nanodisc |

| HS-AFM | High-speed Atomic Force Microscopy |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| NBD | Nucleotide Binding Domain |

| cryo-EM | cryo-electron microscopy |

References

- Staud, F.; Ceckova, M.; Micuda, S.; Pavek, P. Expression and Function of P-Glycoprotein in Normal Tissues: Effect on Pharmacokinetics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010, 596, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharom, F.J. The P-Glycoprotein Multidrug Transporter. Essays Biochem. 2011, 50, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouly, S.; Paine, M.F. P-Glycoprotein Increases from Proximal to Distal Regions of Human Small Intestine. Pharm. Res. 2003, 20, 1595–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiebaut, F.; Tsuruo, T.; Hamada, H.; Gottesman, M.M.; Pastan, I.; Willingham, M.C. Immunohistochemical Localization in Normal Tissues of Different Epitopes in the Multidrug Transport Protein P170: Evidence for Localization in Brain Capillaries and Crossreactivity of One Antibody with a Muscle Protein. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1989, 37, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordon-Cardo, C.; O’Brien, J.P.; Boccia, J.; Casals, D.; Bertino, J.R.; Melamed, M.R. Expression of the Multidrug Resistance Gene Product (P-Glycoprotein) in Human Normal and Tumor Tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1990, 38, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roepe, P. The P-Glycoprotein Efflux Pump: How Does It Transport Drugs? J. Membr. Biol. 1998, 166, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, K.; Taguchi, Y.; Morishima, M. How Does P-Glycoprotein Recognize Its Substrates? Semin. Cancer Biol. 1997, 8, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.B. Drugs as P-Glycoprotein Substrates, Inhibitors, and Inducers. Drug Metab. Rev. 2002, 34, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelig, A. A General Pattern for Substrate Recognition by P-Glycoprotein. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998, 251, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Wang-Kan, X.; Neuberger, A.; Van Veen, H.W.; Pos, K.M.; Piddock, L.J.V.; Luisi, B.F. Multidrug Efflux Pumps: Structure, Function and Regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 523–539, Correction in Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Berridge, G.; Higgins, C.F.; Mistry, P.; Charlton, P.; Callaghan, R. Communication between Multiple Drug Binding Sites on P-Glycoprotein. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000, 58, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeger, M.A.; van Veen, H.W. Molecular Basis of Multidrug Transport by ABC Transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2009, 1794, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, M.M.; Pastan, I.; Ambudkar, S.V. P-Glycoprotein and Multidrug Resistance. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1996, 6, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.H.; Yamazaki, M. Role of P-Glycoprotein in Pharmacokinetics: Clinical Implications: Clinical Implications. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2003, 42, 59–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehne, G. P-Glycoprotein as a Drug Target in the Treatment of Multidrug Resistant Cancer. Curr. Drug Targets 2000, 1, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparreboom, A.; van Asperen, J.; Mayer, U.; Schinkel, A.H.; Smit, J.W.; Meijer, D.K.; Borst, P.; Nooijen, W.J.; Beijnen, J.H.; van Tellingen, O. Limited Oral Bioavailability and Active Epithelial Excretion of Paclitaxel (Taxol) Caused by P-Glycoprotein in the Intestine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 2031–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, S.B.; Cohen, D.; Rao, S.; Ringel, I.; Shen, H.J.; Yang, C.P. Taxol: Mechanisms of Action and Resistance. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 1993, 15, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aller, S.G.; Yu, J.; Ward, A.; Weng, Y.; Chittaboina, S.; Zhuo, R.; Harrell, P.M.; Trinh, Y.T.; Zhang, Q.; Urbatsch, I.L.; et al. Structure of P-Glycoprotein Reveals a Molecular Basis for Poly-Specific Drug Binding. Science 2009, 323, 1718–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Kowal, J.; Broude, E.; Roninson, I.; Locher, K.P. Structural Insight into Substrate and Inhibitor Discrimination by Human P-Glycoprotein. Science 2019, 363, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosol, K.; Romane, K.; Irobalieva, R.N.; Alam, A.; Kowal, J.; Fujita, N.; Locher, K.P. Cryo-EM Structures Reveal Distinct Mechanisms of Inhibition of the Human Multidrug Transporter ABCB1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26245–26253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaghan, R.; Luk, F.; Bebawy, M. Inhibition of the Multidrug Resistance P-Glycoprotein: Time for a Change of Strategy? Drug Metab. Dispos. 2014, 42, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.B.; Szewczyk, P.; Grimard, V.; Lee, C.-W.; Martinez, L.; Doshi, R.; Caya, A.; Villaluz, M.; Pardon, E.; Cregger, C.; et al. Structures of P-Glycoprotein Reveal Its Conformational Flexibility and an Epitope on the Nucleotide-Binding Domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13386–13391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, R.P.; Jayachandra Babu, R.; Srinivas, N.R. Therapeutic Potential and Utility of Elacridar with Respect to P-Glycoprotein Inhibition: An Insight from the Published in Vitro, Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2017, 42, 915–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankstahl, J.P.; Bankstahl, M.; Römermann, K.; Wanek, T.; Stanek, J.; Windhorst, A.D.; Fedrowitz, M.; Erker, T.; Müller, M.; Löscher, W.; et al. Tariquidar and Elacridar Are Dose-Dependently Transported by P-Glycoprotein and Bcrp at the Blood-Brain Barrier: A Small-Animal Positron Emission Tomography and in Vitro Study. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2013, 41, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi-Suzuki, N.; Adachi, N.; Moriya, T.; Yasuda, S.; Kawasaki, M.; Suzuki, K.; Ogasawara, S.; Anzai, N.; Senda, T.; Murata, T. Cryo-EM Structure of P-Glycoprotein Bound to Triple Elacridar Inhibitor Molecules. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 709, 149855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goebel, J.; Chmielewski, J.; Hrycyna, C.A. The Roles of the Human ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters P-Glycoprotein and ABCG2 in Multidrug Resistance in Cancer and at Endogenous Sites: Future Opportunities for Structure-Based Drug Design of Inhibitors. Canc. Drug Resist. 2021, 4, 784–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, T.; Uchihashi, T.; Kodera, N. High-Speed AFM and Applications to Biomolecular Systems. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013, 42, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karner, A.; Nimmervoll, B.; Plochberger, B.; Klotzsch, E.; Horner, A.; Knyazev, D.G.; Kuttner, R.; Winkler, K.; Winter, L.; Siligan, C.; et al. Tuning Membrane Protein Mobility by Confinement into Nanodomains. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansky, S.; Betancourt, J.M.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Kim, E.D.; Paknejad, N.; Nimigean, C.M.; Yuan, P.; Scheuring, S. A Pentameric TRPV3 Channel with a Dilated Pore. Nature 2023, 621, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumino, A.; Sumikama, T.; Zhao, Y.; Flechsig, H.; Umeda, K.; Kodera, N.; Konno, H.; Hattori, M.; Shibata, M. High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy Reveals Fluctuations and Dimer Splitting of the N-Terminal Domain of GluA2 Ionotropic Glutamate Receptor-Auxiliary Subunit Complex. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 25018–25035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodan, A.; Amyot, R.; Umeda, K.; Ogasawara, F.; Kimura, Y.; Kodera, N.; Ueda, K. Direct Visualization of ATP-Binding Cassette Protein A1 Mediated Nascent High-Density Lipoprotein Biogenesis by High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 13563–13570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchihashi, T.; Iino, R.; Ando, T.; Noji, H. High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy Reveals Rotary Catalysis of Rotorless F1-ATPase. Science 2011, 333, 755–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culbertson, A.T.; Liao, M. Cryo-EM of Human P-Glycoprotein Reveals an Intermediate Occluded Conformation during Active Drug Transport. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tama, F.; Sanejouand, Y. Conformational Change of Proteins Arising from Normal Mode Calculations. Protein Eng. 2001, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.-C.; Verhalen, B.; Wilkens, S.; Mchaourab, H.S.; Tajkhorshid, E. On the Origin of Large Flexibility of P-Glycoprotein in the Inward-Facing State. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 19211–19220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, G.R.; Kots, E.; Robertson, J.L.; Lansky, S.; Khelashvili, G.; Weinstein, H.; Scheuring, S. Localization Atomic Force Microscopy. Nature 2021, 594, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodan, A.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nakatsu, T.; Matsuoka, K.; Kimura, Y.; Ueda, K.; Kato, H. Inward- and Outward-Facing X-Ray Crystal Structures of Homodimeric P-Glycoprotein CmABCB1. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Mizutani, K.; Maruyama, S.; Shimono, K.; Imai, F.L.; Muneyuki, E.; Kakinuma, Y.; Ishizuka-Katsura, Y.; Shirouzu, M.; Yokoyama, S.; et al. Crystal Structures of the ATP-Binding and ADP-Release Dwells of the V1 Rotary Motor. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjani, A.; Zhang, H.; Fleet, D.J. Non-Uniform Refinement: Adaptive Regularization Improves Single-Particle Cryo-EM Reconstruction. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P.; Lohkamp, B.; Scott, W.G.; Cowtan, K. Features and Development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjani, A.; Fleet, D.J. 3D Variability Analysis: Resolving Continuous Flexibility and Discrete Heterogeneity from Single Particle Cryo-EM. J. Struct. Biol. 2021, 213, 107702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaoka, Y.; Mori, T.; Nagaike, W.; Itaya, S.; Nonaka, Y.; Kohga, H.; Haruyama, T.; Sugano, Y.; Miyazaki, R.; Ichikawa, M.; et al. AFM Observation of Protein Translocation Mediated by One Unit of SecYEG-SecA Complex. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, T.; Kodera, N.; Takai, E.; Maruyama, D.; Saito, K.; Toda, A. A High-Speed Atomic Force Microscope for Studying Biological Macromolecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 12468–12472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gur, M.; Zomot, E.; Bahar, I. Global Motions Exhibited by Proteins in Micro- to Milliseconds Simulations Concur with Anisotropic Network Model Predictions. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 121912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Miyashita, O.; Tama, F. Modeling Conformational Transitions of Biomolecules from Atomic Force Microscopy Images Using Normal Mode Analysis. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 9363–9372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirion, M.M. Large Amplitude Elastic Motions in Proteins from a Single-Parameter, Atomic Analysis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 1905–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tama, F.; Brooks, C.L., 3rd. The Mechanism and Pathway of PH Induced Swelling in Cowpea Chlorotic Mottle Virus. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 318, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kanaoka, Y.; Hamaguchi-Suzuki, N.; Nonaka, Y.; Yamashita, S.; Miyashita, O.; Ito, A.; Ogasawara, S.; Tama, F.; Murata, T.; Uchihashi, T. Visualizing the Functional Dynamics of P-Glycoprotein and Its Modulation by Elacridar via High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010356

Kanaoka Y, Hamaguchi-Suzuki N, Nonaka Y, Yamashita S, Miyashita O, Ito A, Ogasawara S, Tama F, Murata T, Uchihashi T. Visualizing the Functional Dynamics of P-Glycoprotein and Its Modulation by Elacridar via High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010356

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanaoka, Yui, Norie Hamaguchi-Suzuki, Yuto Nonaka, Soichi Yamashita, Osamu Miyashita, Atsuyuki Ito, Satoshi Ogasawara, Florence Tama, Takeshi Murata, and Takayuki Uchihashi. 2026. "Visualizing the Functional Dynamics of P-Glycoprotein and Its Modulation by Elacridar via High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010356

APA StyleKanaoka, Y., Hamaguchi-Suzuki, N., Nonaka, Y., Yamashita, S., Miyashita, O., Ito, A., Ogasawara, S., Tama, F., Murata, T., & Uchihashi, T. (2026). Visualizing the Functional Dynamics of P-Glycoprotein and Its Modulation by Elacridar via High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010356