Nanomechanical and Thermodynamic Alterations of Red Blood Cells in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Implications for Disease and Treatment Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Clinical and Hematological Characteristics of the CLL Patients and Healthy Individuals

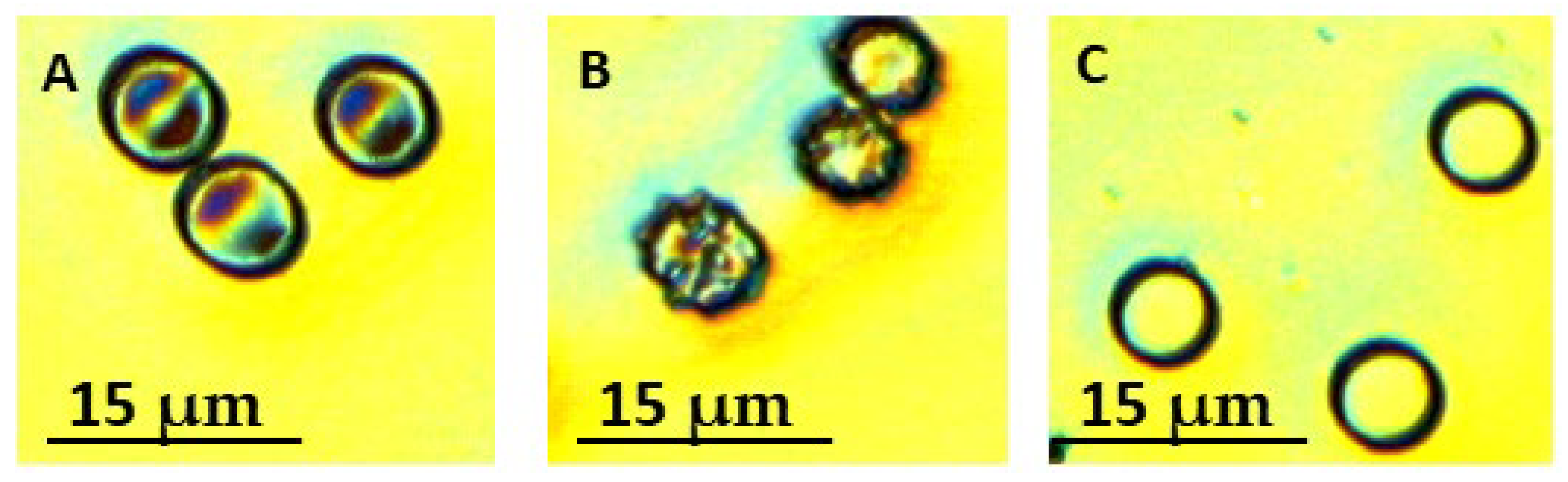

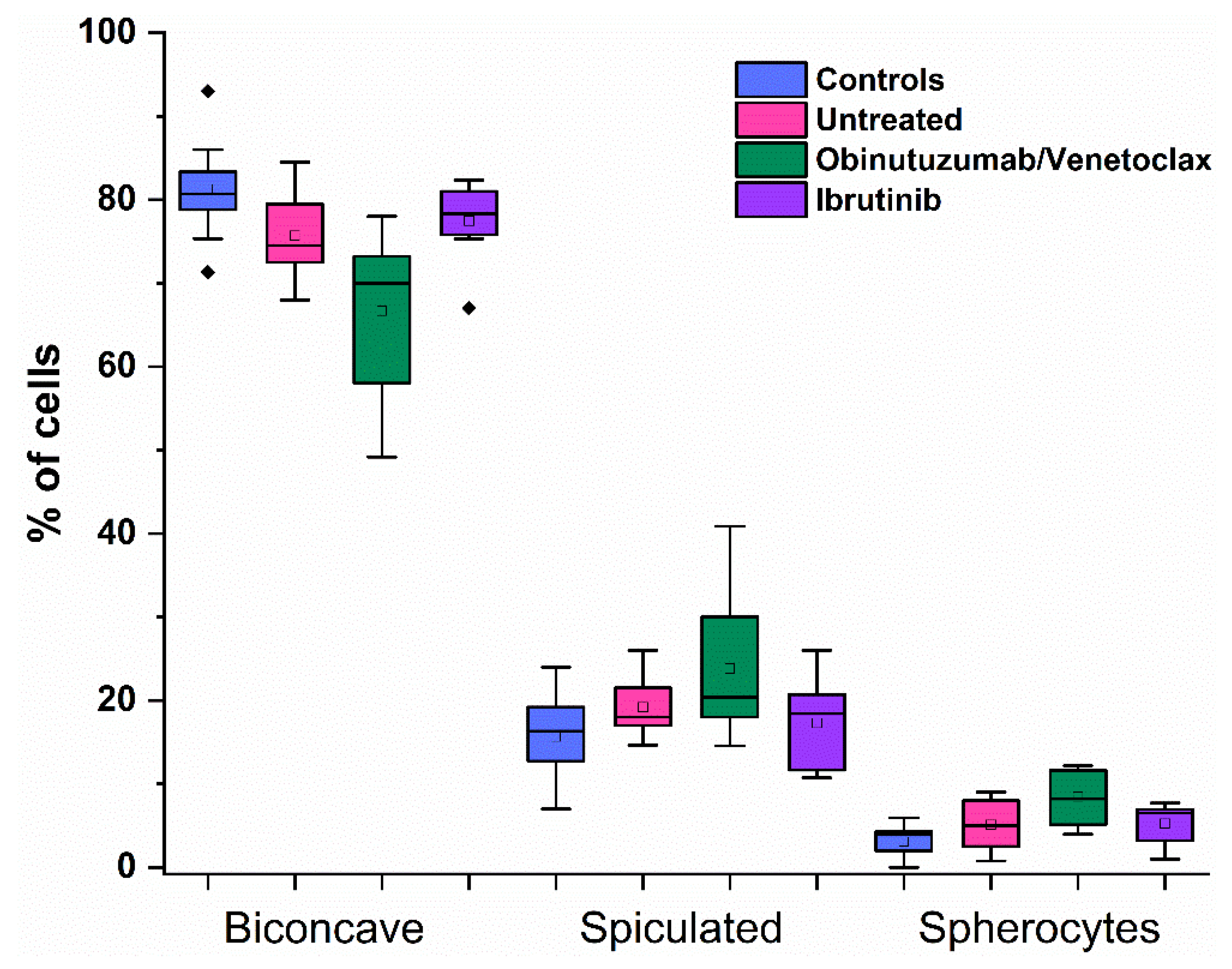

2.2. RBC Morphology in CLL Patients

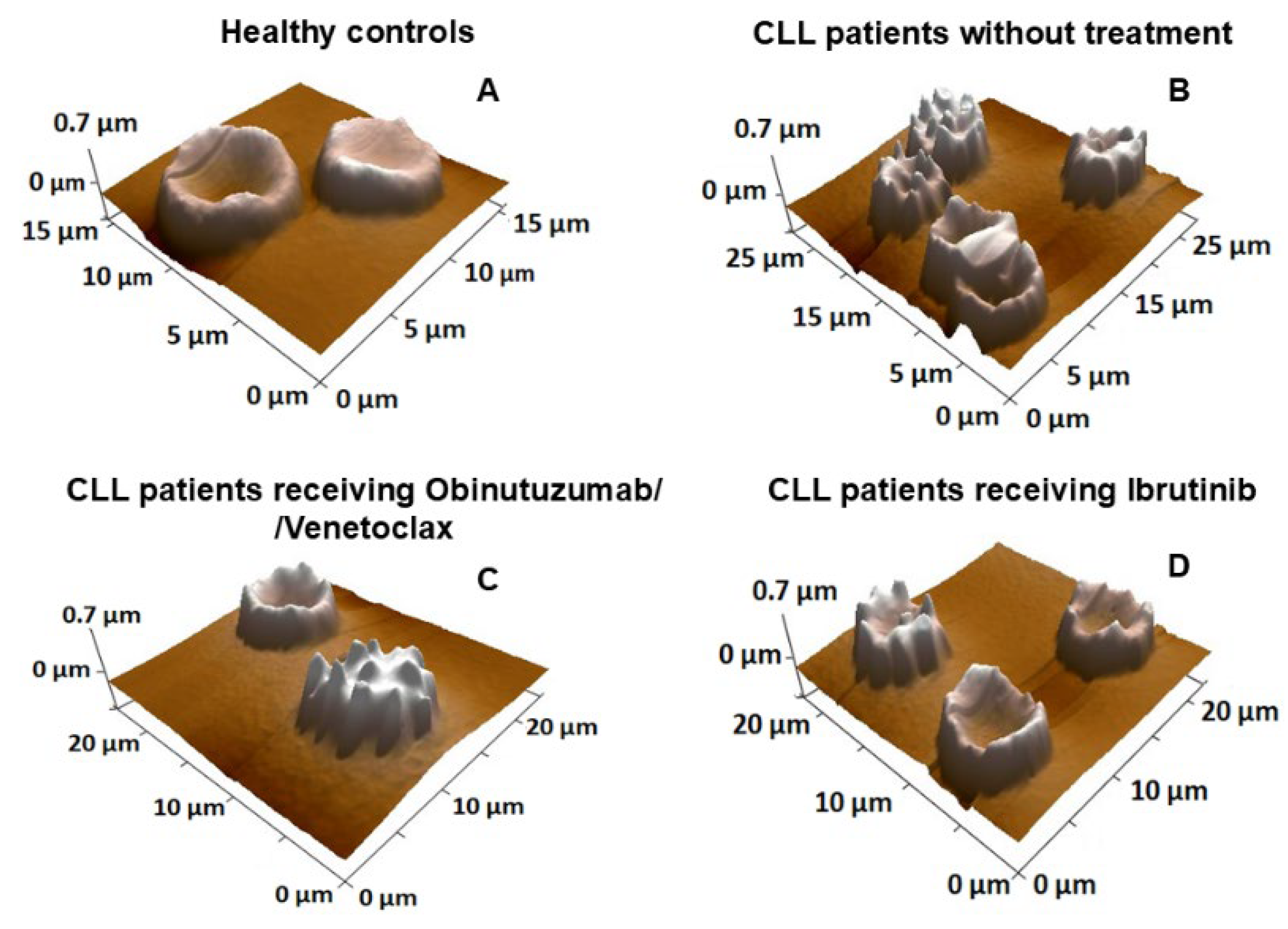

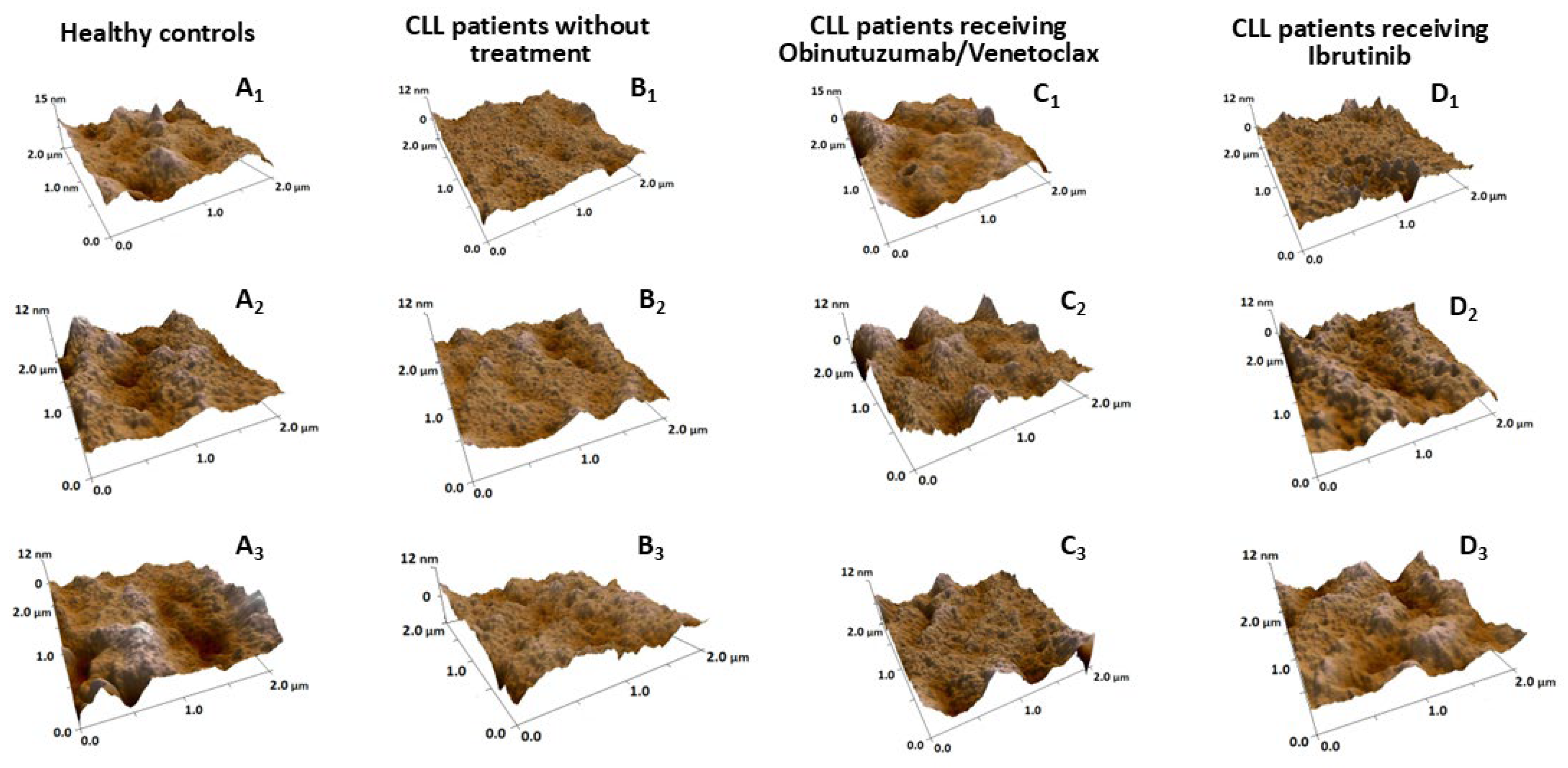

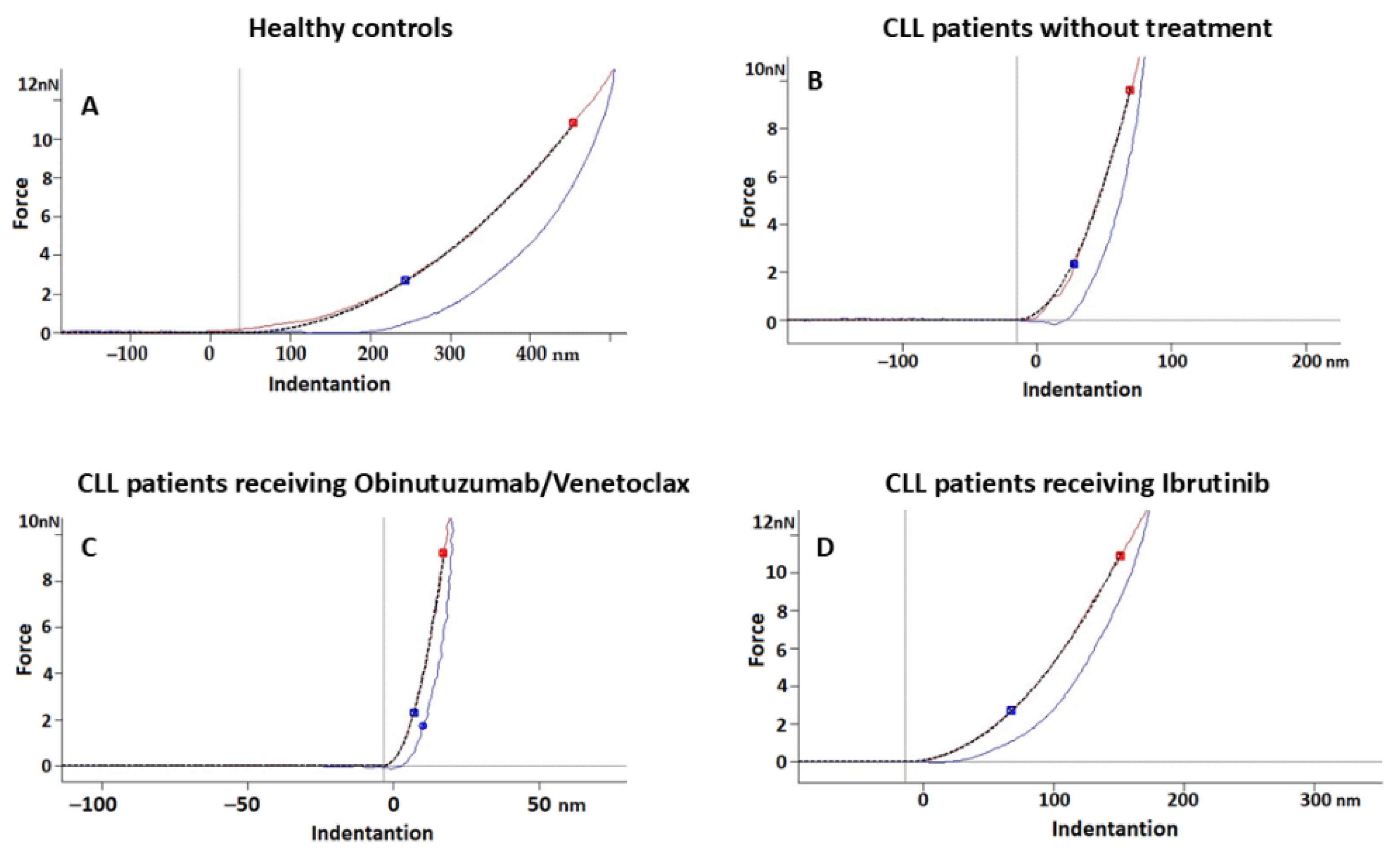

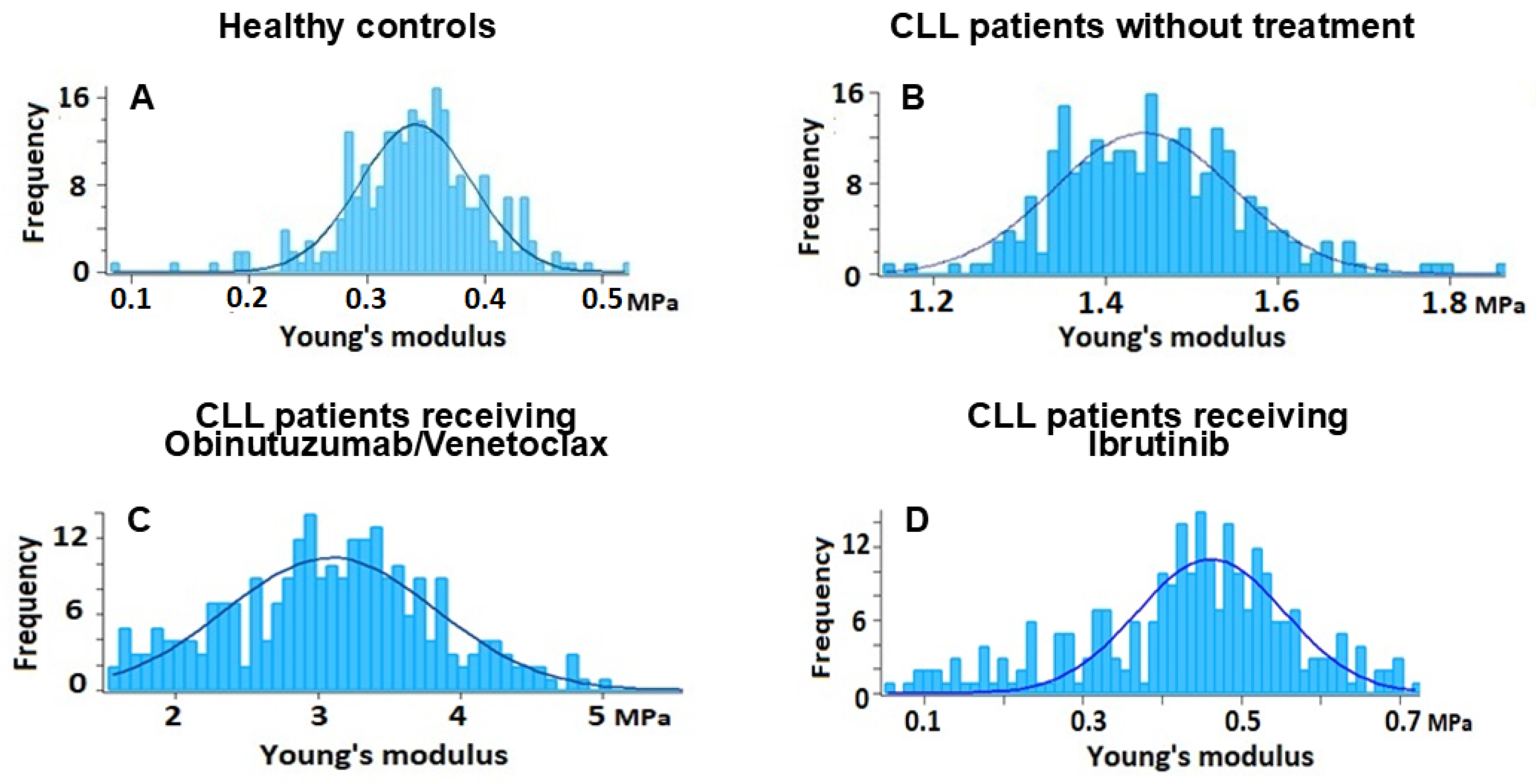

2.3. Nanostructural and Nanomechanical Parameters of RBCs in CLL Patients

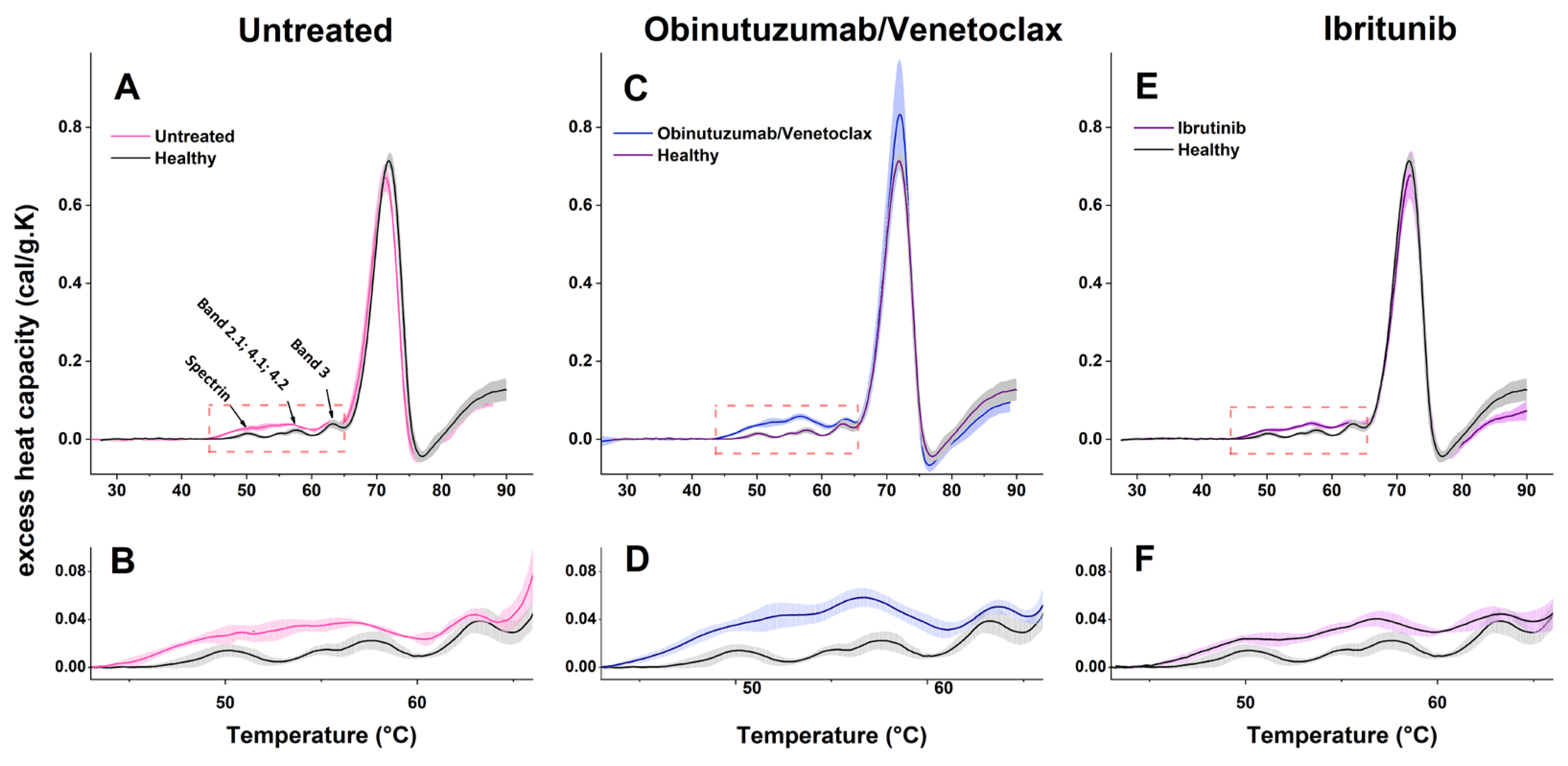

2.4. Calorimetric Properties of RBCs in CLL and the Healthy State

3. Discussion

3.1. RBC Nanostructural and Nanomechanical Alteration in CLL

3.2. Treatment-Related Changes in RBC Properties

3.3. Adhesive Forces in CLL RBCs

3.4. Thermodynamic Behavior of RBCs in CLL

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Selection of Patients and Ethics Statement

4.2. Blood Collection and Sample Preparation

4.3. Optical Microscopy

4.4. Atomic Force Microscopy

4.4.1. Morphometric Analysis

4.4.2. Young’s Modulus Measurements

4.4.3. Adhesion Force Measurements

4.5. DSC Measurements

4.6. Clinical and Hematological Indices

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RBCs | red blood cells |

| CLL | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| IBR | Ibrutinib |

| BCR | B-cell receptor |

| AIHA | autoimmune hemolytic anemia |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| Hb | hemoglobin |

| AAI | Aggregate-Area Indicator |

References

- Kipps, T.J.; Stevenson, F.K.; Wu, C.J.; Croce, C.M.; Packham, G.; Wierda, W.G.; O’Brien, S.; Gribben, J.; Rai, K. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 16096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombie, J.; Davids, M.S. IGHV mutational status testing in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2017, 92, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, N.; Thompson, P.; Burger, J.; Ferrajoli, A.; Takahashi, K.; Estrov, Z.; Borthakur, G.; Bose, P.; Kadia, T.; Pemmaraju, N.; et al. Ibrutinib, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and obinutuzumab (iFCG) regimen for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) with mutated IGHV and without TP53 aberrations. Leukemia 2021, 35, 3421–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braish, J.; Cerchione, C.; Ferrajoli, A. An overview of prognostic markers in patients with CLL. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1371057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonolo de Campos, C.; McCabe, C.E.; Bruins, L.A.; O’Brien, D.R.; Brown, S.; Tschumper, R.C.; Allmer, C.; Zhu, Y.X.; Rabe, K.G.; Parikh, S.A.; et al. Genomic characterization of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in patients of African ancestry. Blood Cancer J. 2025, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr, M.; Roeker, L. A History of Targeted Therapy Development and Progress in Novel-Novel Combinations for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL). Cancers 2023, 15, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogler, M.; Braun, Y.; Smith, V.M.; Westhoff, M.; Pereira, R.S.; Pieper, M.N.; Anders, M.; Callens, M.; Vervliet, T.; Abbas, M.; et al. The BCL2 family: From apoptosis mechanisms to new advances in targeted therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Tang, F.; Li, Y.; Bai, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, L. Combination of BCL-2 inhibitors and immunotherapy: A promising therapeutic strategy for hematological malignancies. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsouqi, A.; Woyach, J.A. SOHO State of the Art Updates and Next Questions: Covalent Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2025, 25, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunk, P.R.; Mock, J.; Devitt, M.E.; Palkimas, S.; Sen, J.; Portell, C.A.; Williams, M.E. Major Bleeding with Ibrutinib: More Than Expected. Blood 2016, 128, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartermaine, C.; Ghazi, S.M.; Yasin, A.; Awan, F.T.; Fradley, M.; Wiczer, T.; Kalathoor, S.; Ferdousi, M.; Krishan, S.; Habib, A.; et al. Cardiovascular Toxicities of BTK Inhibitors in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: JACC: CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol. 2023, 5, 570–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autore, F.; Pasquale, R.; Innocenti, I.; Fresa, A.; Sora’, F.; Laurenti, L. Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 5804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, D.; Banerjee, D.; Chandra, S.; Banerjee, S.; Chakrabarti, A. Red cell morphology in leukemia, hypoplastic anemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Pathophysiology 2006, 13, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barshtein, G.; Gural, A.; Arbell, D.; Barkan, R.; Livshits, L.; Pajic-Lijakovic, I.; Yedgar, S. Red Blood Cell Deformability Is Expressed by a Set of Interrelated Membrane Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barshtein, G.; Pajic-Lijakovic, I.; Gural, A. Deformability of Stored Red Blood Cells. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 722896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandrova-Watanabe, A.; Abadjieva, E.; Gartcheva, L.; Langari, A.; Ivanova, M.; Guenova, M.; Tiankov, T.; Strijkova, V.; Krumova, S.; Todinova, S. The Impact of Targeted Therapies on Red Blood Cell Aggregation in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Evaluated Using Software Image Flow Analysis. Micromachines 2025, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova-Watanabe, A.; Abadjieva, E.; Ivanova, M.; Gartcheva, L.; Langari, A.; Guenova, M.; Tiankov, T.; Nikolova, E.V.; Krumova, S.; Todinova, S. Quantitative Assessment of Red Blood Cell Disaggregation in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia via Software Image Flow Analysis. Fluids 2025, 10, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barshtein, G.; Livshits, L.; Gural, A.; Arbell, D.; Barkan, R.; Pajic-Lijakovic, I.; Yedgar, S. Hemoglobin Binding to the Red Blood Cell (RBC) Membrane Is Associated with Decreased Cell Deformability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Ming, D.; Zhong, J.; Shannon, C.S.; Rojas-Carabali, W.; Agrawal, K.; Ai, Y.; Agrawal, R. Pathophysiological Associations and Measurement Techniques of Red Blood Cell Deformability. Biosensors 2025, 15, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahyayauch, H.; García-Arribas, A.B.; Sot, J.; González-Ramírez, E.J.; Busto, J.V.; Monasterio, B.G.; Jiménez-Rojo, N.; Contreras, F.X.; Rendón-Ramírez, A.; Martin, C.; et al. Pb(II) Induces Scramblase Activation and Ceramide-Domain Generation in Red Blood Cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girasole, M.; Pompeo, G.; Cricenti, A.; Congiu-Castellano, A.; Andreola, F.; Serafino, A.; Frazer, B.H.; Boumis, G.; Amiconi, G. Roughness of the plasma membrane as an independent morphological parameter to study RBCs: A quantitative atomic force microscopy investigation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2007, 1768, 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarelli, S.; Krumova, S.; Todinova, S.; Taneva, S.G.; Lenzi, E.; Mussi, V.; Longo, G.; Girasole, M. Insight into the Morphological Pattern Observed Along the Erythrocytes’ Aging: Coupling Quantitative AFM Data to microcalorimetry and Raman Spectroscopy. J. Mol. Recognit. 2018, 31, e2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, G.; Dinarelli, S.; Collacchi, F.; Girasole, M. Comparing Nanomechanical Properties and Membrane Roughness Along the Aging of Human Erythrocytes. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandts, J.F.; Erickson, L.; Lysko, K.; Schwartz, A.T.; Taverna, R.D. Calorimetric studies of the structural transitions of the human erythrocyte membrane: The involvement of spectrin in the A transition. Biochemistry 1977, 16, 3450–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepock, J.R. Measurement of protein stability and protein denaturation in cells using differential scanning calorimetry. Methods 2005, 35, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davio, S.R.; Low, P.S. Characterization of the calorimetric C transition of the human erythrocyte membrane. Biochemistry 1982, 21, 3585–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, V.; Diederich, L.; Keller, T.C.S., IV; Kramer, C.M.; Lückstädt, W.; Panknin, C.; Suvorava, T.; Isakson, B.E.; Kelm, M.; Cortese-Krott, M.M. Red Blood Cell Function and Dysfunction: Redox Regulation, Nitric Oxide Metabolism, Anemia. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 26, 718–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himbert, S.; Rheinstädter, M.C. Structural and mechanical properties of the red blood cell’s cytoplasmic membrane seen through the lens of biophysics. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 953257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadis, D. Atomic force microscopy for the study of membrane proteins. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caligaris-Cappio, F. Inflammation, the microenvironment and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica 2011, 96, 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Suh, J.S.; Kim, Y.K. Red Blood Cell Deformability and Distribution Width in Patients with Hematologic Neoplasms. Clin. Lab. 2022, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vom Stein, A.F.; Hallek, M.; Nguyen, P.-H. Role of the tumor microenvironment in CLL pathogenesis. Semin. Hematol. 2024, 61, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T. IL-6 in inflammation, autoimmunity and cancer. Int. Immunol. 2021, 33, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, R.; Remigante, A.; Cordaro, M.; Trichilo, V.; Loddo, S.; Dossena, S.; Marino, A. Impact of acute inflammation on Band 3 protein anion exchange capability in human erythrocytes. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 128, 1242–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vieyra, I.; Hernández-Rojo, I.; Rosales-García, V.H.; Chávez-Piña, A.E.; Cerecedo, D. Oxidative Stress and Cytoskeletal Reorganization in Hypertensive Erythrocytes. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.; Lutz, R.J.; Cotter, T.G.; O’Connor, R. Erythrocyte survival is promoted by plasma and suppressed by a Bak-derived BH3 peptide that interacts with membrane-associated Bcl-XL. Blood 2002, 99, 3439–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golay, J.; Da Roit, F.; Bologna, L.; Ferrara, C.; Leusen, J.H.; Rambaldi, A.; Klein, C.; Introna, M. Glycoengineered CD20 antibody obinutuzumab activates neutrophils and mediates phagocytosis through CD16B more efficiently than rituximab. Blood 2013, 122, 3482–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, C.L.; Morschhauser, F.; Sehn, L.; Dixon, M.; Houghton, R.; Lamy, T.; Fingerle-Rowson, G.; Wassner-Fritsch, E.; Gribben, J.G.; Hallek, M.; et al. Cytokine release in patients with CLL treated with obinutuzumab and possible relationship with infusion-related reactions. Blood 2015, 126, 2646–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mameri, A.; Bournine, L.; Mouni, L.; Bensalem, S.; Iguer-Ouada, M. Oxidative stress as an underlying mechanism of anticancer drugs cytotoxicity on human red blood cells’ membrane. Toxicol. Vitro 2021, 72, 105106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Leong, H.C.; Datta, A.; Gopal, V.; Kumar, A.P.; Yap, C.T. PI3K/AKT Signaling Tips the Balance of Cytoskeletal Forces for Cancer Progression. Cancers 2022, 14, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Liu, C.; Upadhyaya, A. The pivotal position of the actin cytoskeleton in the initiation and regulation of B cell receptor activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1838, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, S.; Marino, A.; Remigante, A.; Morabito, R. Redox Homeostasis in Red Blood Cells: From Molecular Mechanisms to Antioxidant Strategies. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cilek, N.; Ugurel, E.; Goksel, E.; Yalcin, O. Signaling mechanisms in red blood cells: A view through the protein phosphorylation and deformability. J. Cell. Physiol. 2024, 239, e30958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greil, R.; Tedeschi, A.; Moreno, C.; Anz, B.; Larratt, L.; Simkovic, M.; Gill, D.; Gribben, J.G.; Flinn, I.W.; Wang, Z.; et al. Pretreatment with ibrutinib reduces cytokine secretion and limits the risk of obinutuzumab-induced infusion-related reactions in patients with CLL: Analysis from the iLLUMINATE study. Ann. Hematol. 2021, 100, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, F.A. Membrane lipid alterations in hemoglobinopathies. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2007, 2007, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, F.A. Hemoglobin S polymerization and red cell membrane changes. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 28, 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuypers, F.A. Phospholipid asymmetry in health and disease. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 1998, 5, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, E.; El Nemer, W.; Wautier, M.P.; Renaud, O.; Tchernia, G.; Delaunay, J.; Le Van Kim, C.; Colin, Y. Role of the interaction between Lu/BCAM and the spectrin-based membrane skeleton in the increased adhesion of hereditary spherocytosis red cells to laminin. Br. J. Haematol. 2010, 148, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, A.; García-Vicente, R.; Morales, M.L.; Ortiz-Ruiz, A.; Martínez-López, J.; Linares, M. Protein Carbonylation and Lipid Peroxidation in Hematological Malignancies. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaleo, A.; Ferru, E.; Pau, E.C.; Khadjavi, A.; Mandili, G.; Mattè, A.; Spano, A.; De Franceschi, L.; Pippia, P.; Turrini, F. Band 3 Erythrocyte Membrane Protein Acts as Redox Stress Sensor Leading to Its Phosphorylation by p72 Syk. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 6051093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Z.H. Structure, dynamics and assembly of the ankyrin complex on human red blood cell membrane. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2022, 29, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wautier, M.P.; Héron, E.; Picot, J.; Colin, Y.; Hermine, O.; Wautier, J.L. Red blood cell phosphatidylserine exposure is responsible for increased erythrocyte adhesion to endothelium in central retinal vein occlusion. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011, 9, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarralde-Iragorri, M.A.; Lefevre, S.D.; Cochet, S.; Hoss, S.E.; Brousse, V.; Filipe, A.; Nemer, W.E. Oxidative stress activates red cell adhesion to laminin in sickle cell disease. Haematologica 2021, 106, 2478–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, P.C.; Gao, X.; Herppich, A.; Hollon, W.; Chitlur, M.B.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Tarasev, M. Ex Vivo Evaluation of Red Blood Cell Adhesion and Whole Blood Thrombosis in Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency. Blood 2021, 138, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, C. Disease-specific complications of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2008, 2008, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montresor, A.; Toffali, L.; Rigo, A.; Ferrarini, I.; Vinante, F.; Laudanna, C. CXCR4- and BCR-triggered integrin activation in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells depends on JAK2-activated Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 35123–35140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, W.; Franzen, C.A.; Guo, H.; Lee, J.; Li, Y.; Sukhanova, M.; Sheng, D.; Venkataraman, G.; Ming, M.; et al. Inhibition of B-cell receptor signaling disrupts cell adhesion in mantle cell lymphoma via RAC2. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vani, R.; Anusha, B.A.; Christina, R.M.; Kavin, P.; Mohammed, O.; Inchara, S.; Kavvyasruthi, U.J.; Sadiya, S.; Sindhu, H.S. Band 3 Protein: A Critical Component of Erythrocyte. In Red Blood Cells—Properties and Functions; Rajashekaraiah, V., Ed.; Intech Open: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferru, E.; Giger, K.; Pantaleo, A.; Campanella, E.; Grey, J.; Ritchie, K.; Vono, R.; Turrini, F.; Low, P.S. Regulation of membrane-cytoskeletal interactions by tyrosine phosphorylation of erythrocyte band 3. Blood 2011, 117, 5998–6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallek, M.; Cheson, B.D.; Catovsky, D.; Caligaris-Cappio, F.; Dighiero, G.; Döhner, H.; Hillmen, P.; Keating, M.; Montserrat, E.; Chiorazzi, N.; et al. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood 2018, 131, 2745–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallek, M.; Cheson, B.D.; Catovsky, D.; Caligaris-Cappio, F.; Dighiero, G.; Döhner, H.; Hillmen, P.; Keating, M.J.; Montserrat, E.; Rai, K.R.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood 2008, 111, 5446–5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durowoju, I.B.; Bhandal, K.S.; Hu, J.; Carpick, B.; Kirkitadze, M. Differential scanning calorimetry—A method for assessing the thermal stability and conformation of protein antigen. J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 121, e55262. [Google Scholar]

| Parameters | Reference Value | Studied Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Controls (n = 17) | Untreated CLL Patients (n = 8) | CLL Patients Receiving Obinutuzumab/ Venetoclax (n = 11) | CLL Patients Receiving Ibrutinib (n = 8) | p-Value (Kruskal–Wallis Test) | ||

| Age (years) | - | 58 (49.0; 65.5) a | 65 (49; 70.8) a | 72 (64.5; 74.8) b | 62.5 (54.3; 73.8) ab | 0.04 |

| Gender (F/M) | 11/6 | 3/5 | 5/6 | 3/5 | ||

| Rai stage | 0 | 1–4 | 1–4 | |||

| Onset of disease (years) | 2.5 (0.75; 9.0) | 4.0 (3.0; 7.0) | 8.0 (5.0; 13.0) | |||

| Treatment duration (years) | 2.0 (1.0; 2.0) | 4.0 (4.0; 5.0) | ||||

| RBC count (T/L) | 4.60–6.20 | 4.45 (4.38; 4.79) a | 5.16 (4.68; 5.26) b | 4.62 (4.46; 4.82) a | 4.91 (4.67; 5.09) a | 0.048 |

| Hb (g/L) | 140.00–180.00 | 143.5 (140; 151) a | 148.5 (141; 160) a | 140.0 (120; 148) b | 141 (138; 147) a | 0.009 |

| Ht (L/L) | 0.40–0.54 | 0.44 (0.42; 0.47) | 0.44 (0.42; 0.46) | 0.41 (0.37; 0.43) | 0.43 (0.41; 0.46) | 0.06 |

| MCV (fl) | 80.00–95.00 | 89.8 (87.4; 93.0) | 87.9 (85.8; 93.8) | 88.1 (82.9; 93.6) | 89.2 (85.9; 91.0) | 0.88 |

| MCH (pg/L) | 27.00–32.00 | 30.1 (29.1; 31.4) | 30.3 (28.5; 31.5) | 301 (27.7; 31.3) | 29.7 (27.5; 30.2) | 0.41 |

| MCHC (g/L) | 320.00–360.00 | 343.0 (327; 349) | 339.5 (324; 345) | 337.0 (328; 341) | 333 (306; 344) | 0.43 |

| RDW% | 11.60–14.80 | 13.2 (12.7; 14.3) | 13.5 (13.2; 15.4) | 13.9 (13.3; 14.7) | 14.1 (13.5; 14.6) | 0.95 |

| WBC | 3.50–10.50 | 5.8 (5.4; 6.6) | 21.2 (10.1; 71.2) * | 3.89 (2.82; 4.20) | 6.1 (4.8; 8.1) | 0.015 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 3.40–20.50 | 16.3 (7.4; 18.5) | 12.0 (8.8; 37.9) | 13.0 (9.5; 21.5) | 13.4 (11.3; 18.4) | 0.73 |

| Lymphocytes (ABS) | 1.10–3.80 | 1.84 (1.79; 2.14) | 15.8 (5.4; 62.4) * | 1.2 (1.0; 1.5) | 1.8 (1.1; 3.4) | <0.0001 |

| Platelet count ×109/L | 289 (192; 376) | 200 (168; 239) | 161 (131; 214) | 154 (142; 195) | 0.43 | |

| NRBCs/erythroblasts (g/L) | 0.00–0.20 | Not measured | None established | None established | None established | - |

| Sample (n) | Rrms (nm) | Ea (MPa) | Adhesive Forces (pN) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBCs from healthy donors (17) | 4.81 (4.07; 5.29) a | 0.336 (0.28; 0.43) a | 266.5 (177; 321.8) a |

| RBCs from untreated Patients (8) | 3.55 (2.53; 4.03) b | 1.3 (1.02; 2.03) b | 351.13 (283.9; 387.3) b |

| RBCs from Obinutuzumab/Venetoclax-treated CLL patients (11) | 4.28 (3.19; 6.40) a | 3.53 (2.76; 3.75) c | 350 (248; 513.3) b |

| RBCs from Ibrutinib-treated CLL patients (8) | 4.19 (3.02; 4.71) a | 0.493 (0.31; 0.87) a | 261.14 (211.6; 383.2) a |

| p-value (Kruskal–Wallis test) | 0.007 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Parameters | RBCs from Healthy Controls | RBCs from Untreated Patients | RBCs from Patients Treated with Obinutuzumab/ Venetoclax | RBCs from Patients Treated with Ibrutinib | p-Value (Kruskal–Wallis Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmspectrin (°C) | 50.1 (50.07; 50.2) | 50.7 (50.63; 50.81) | nd | 49.88 (49.7; 49.92) | 0.52 |

| cPspectrin (cal/gK) | 0.014 (0.013; 0.016) a | 0.029 (0.026; 0.030) b | nd | 0.024 (0.023; 0.025) b | <0.001 |

| TmBand2–4 (°C) | 55.2 (55.1; 55.43) a/ 57.5 (57.35; 57.68) a | 54.05 (53.98; 54.22) b/ 56.48 (56.33; 56.76) b | nd/ 56.73 (56.63; 56.89) a | 54.5 (53.61; 54.83) a/ 56.82 (56.41; 57.36) a | <0.001 |

| cPBand2–4 (cal/gK) | 0.0148 (0.0137; 0.0158) a/ 0.023 (0.020; 0.024) a | 0.034 (0.031; 0.035) b/ 0.037 (0.035; 0.040) b | nd/ 0.059 (0.056; 0.062) c | 0.032 (0.030; 0.034) b/ 0.041 (0.039; 0.044) b | <0.001 |

| TmBand3 (°C) | 63.29 (63.16; 63.46) | 63.05 (62.98; 63.16) | 63.7 (63.68; 63.87) | 63.11 (62.78; 63.26) | 0.76 |

| cPBand3 (cal/gK) | 0.038 (0.035; 0.041) a | 0.043 (0.040; 0.046) b | 0.050 (0.047; 0.053) c | 0.045 (0.042; 0.047) b | 0.03 |

| TmHb (°C) | 71.91 (71.77; 72.01) | 71.27 (71.19; 71.38) | 71.92 (71.02; 71.28) | 72.13 (71.99; 72.27) | 0.85 |

| cPHb (cal/gK) | 0.718 (0.707; 0.73) a | 0.677 (0.668; 0.689) b | 0.839 (0.819; 0.859) c | 0.688 (0.671; 0.7) b | <0.001 |

| ΔHcal (cal/g) | 3.84 (3.77; 3.97) a | 3.94 (3.82; 4.05) a | 4.71 (4.57; 4.85) b | 3.99 (3.87; 4.11) a | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Strijkova, V.; Katrova, V.; Ivanova, M.; Langari, A.; Gartcheva, L.; Guenova, M.; Alexandrova-Watanabe, A.; Taneva, S.G.; Krumova, S.; Todinova, S. Nanomechanical and Thermodynamic Alterations of Red Blood Cells in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Implications for Disease and Treatment Monitoring. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010353

Strijkova V, Katrova V, Ivanova M, Langari A, Gartcheva L, Guenova M, Alexandrova-Watanabe A, Taneva SG, Krumova S, Todinova S. Nanomechanical and Thermodynamic Alterations of Red Blood Cells in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Implications for Disease and Treatment Monitoring. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010353

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrijkova, Velichka, Vesela Katrova, Miroslava Ivanova, Ariana Langari, Lidia Gartcheva, Margarita Guenova, Anika Alexandrova-Watanabe, Stefka G. Taneva, Sashka Krumova, and Svetla Todinova. 2026. "Nanomechanical and Thermodynamic Alterations of Red Blood Cells in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Implications for Disease and Treatment Monitoring" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010353

APA StyleStrijkova, V., Katrova, V., Ivanova, M., Langari, A., Gartcheva, L., Guenova, M., Alexandrova-Watanabe, A., Taneva, S. G., Krumova, S., & Todinova, S. (2026). Nanomechanical and Thermodynamic Alterations of Red Blood Cells in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Implications for Disease and Treatment Monitoring. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010353