Alterations of Apolipoprotein A1, E, and J Genes in the Frontal Cortex in an Ischemic Model of Alzheimer’s Disease with 2-Year Survival

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

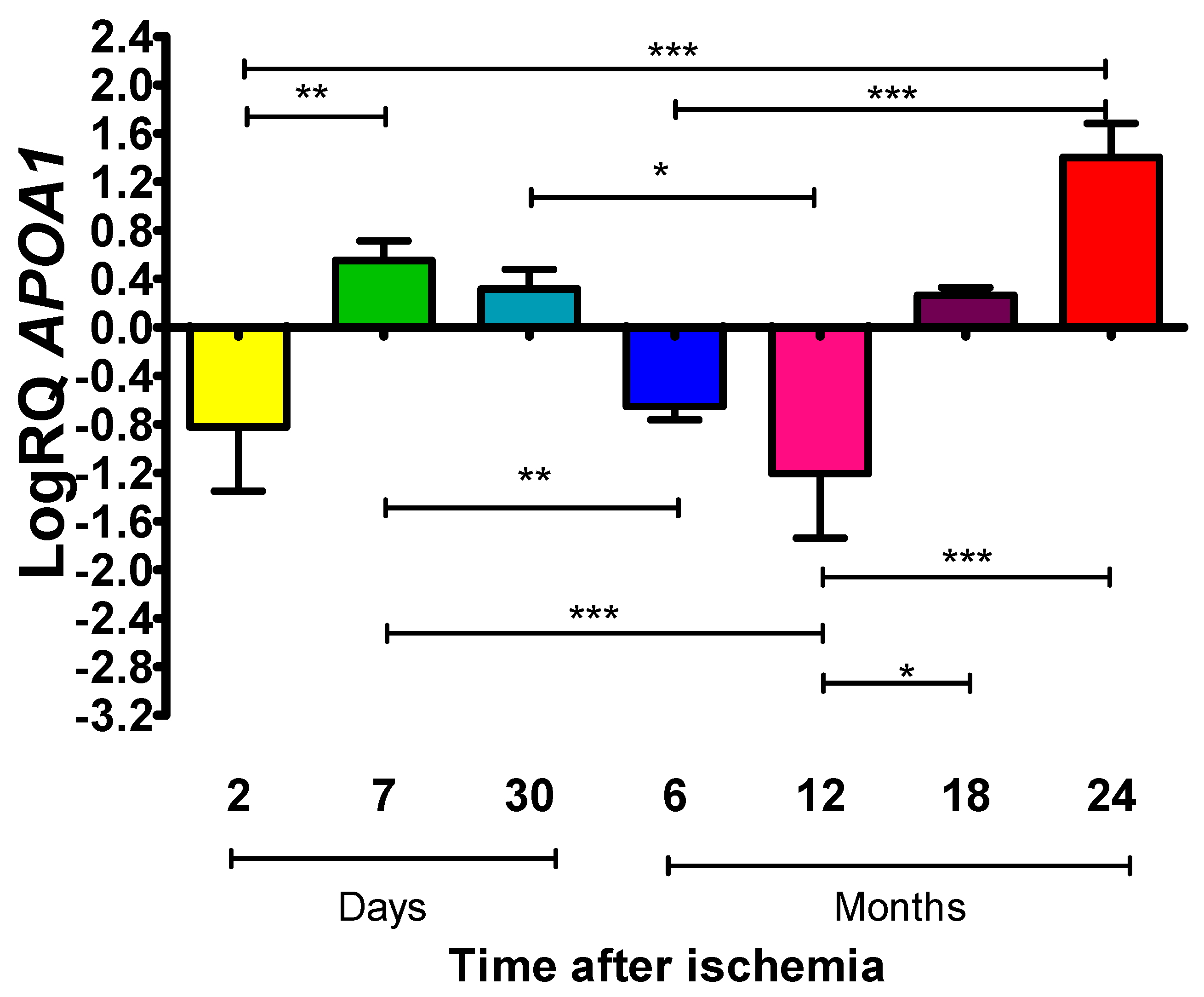

2.1. Mean Expression Levels of ApoA1 in the Frontal Cortex at Various Periods After Global Brain Ischemia in Rats

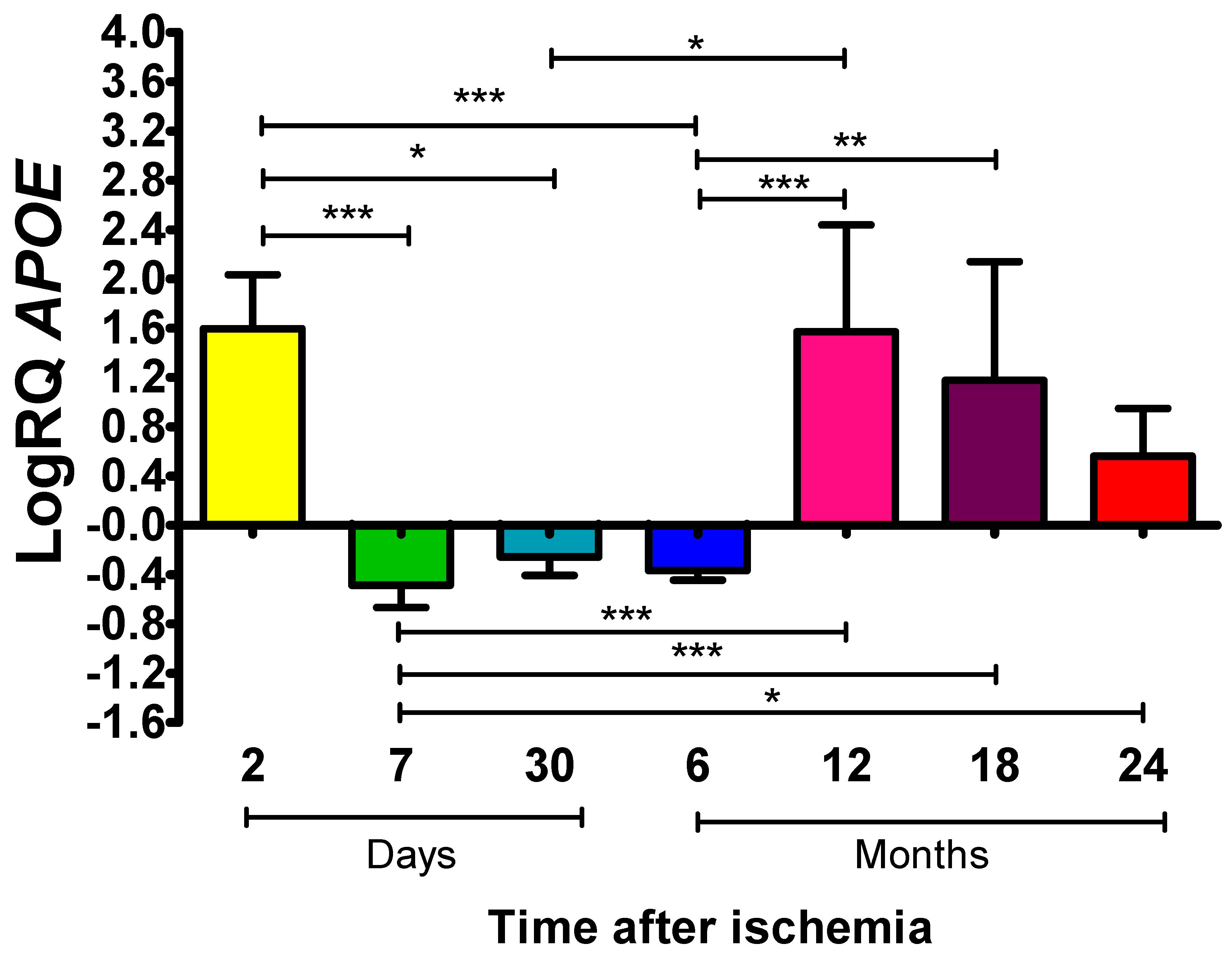

2.2. ApoE Expression Levels in Rat Frontal Cortex Following Global Brain Ischemia

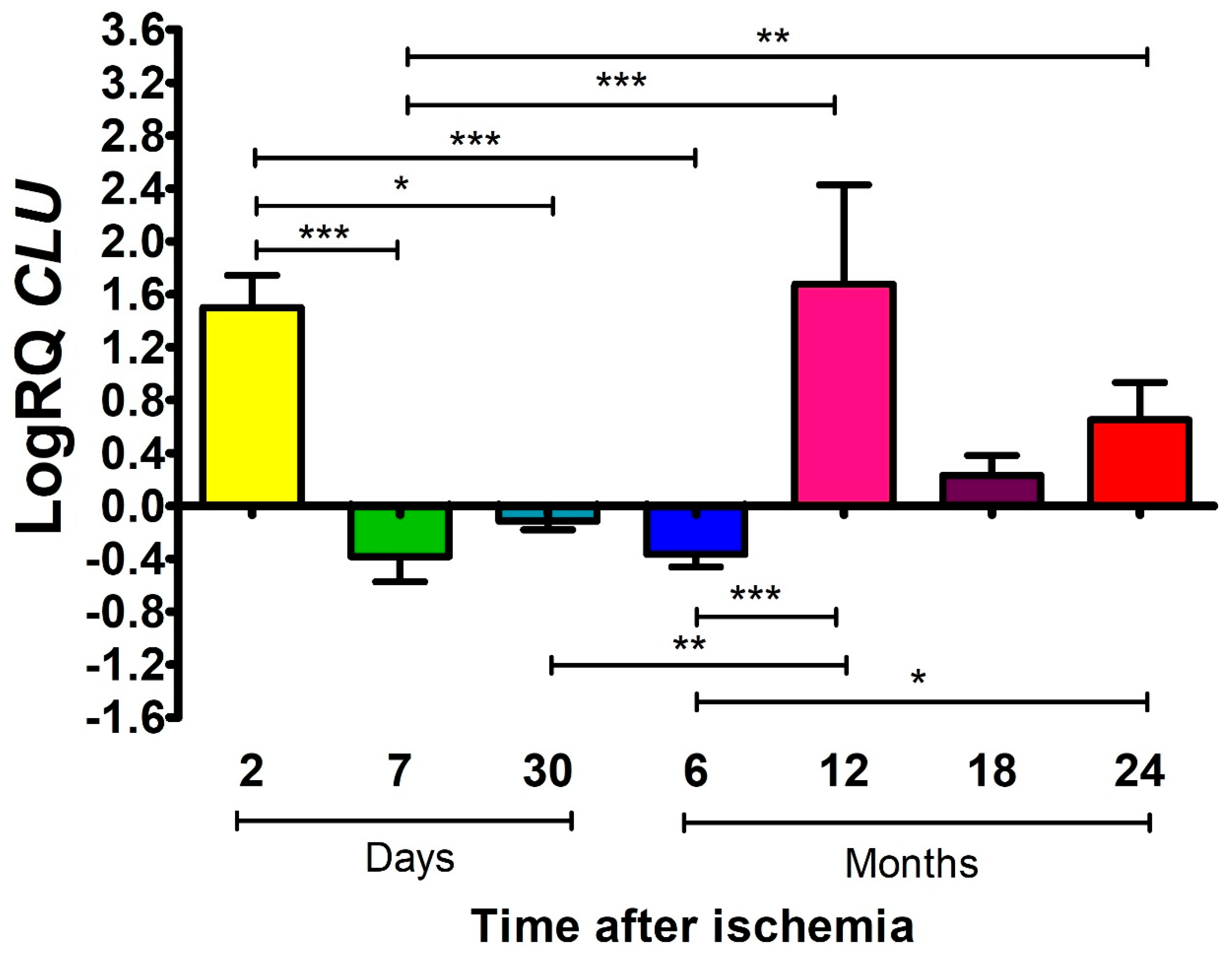

2.3. The Influence of Global Brain Ischemia on the Expression Levels of ApoJ in the Rat Frontal Cortex

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ApoA1 | Apolipoprotein A1 |

| ApoE | Apolipoprotein E |

| ApoJ | Apolipoprotein J |

| Apos | Apolipoproteins |

| CLU | Clusterin |

| CAA | Cerebral amyloid angiopathy |

References

- Kamatham, P.T.; Shukla, R.; Khatri, D.K.; Vora, L.K. Pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease: Breaking the memory barrier. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 101, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, I.; Sehgal, A.; Khandige, P.S.; Imran, M.; Gulati, M.; Khalid Anwer, M.; Elossaily, G.M.; Ali, N.; Wal, P.; et al. The link between Alzheimer’s disease and stroke: A detrimental synergism. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 99, 102388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dammavalam, V.; Rupert, D.; Lanio, M.; Jin, Z.; Nadkarni, N.; Tsirka, S.E.; Bergese, S.D. Dementia after Ischemic Stroke, from Molecular Biomarkers to Therapeutic Options. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Liu, Y.; Deng, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, G. Global regional national epidemiology of ischemic stroke from 1990 to 2021. Eur. J. Neurol. 2024, 31, e16481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamdu, K.S.; Kalra, D.K. Risk of Stroke, Dementia, and Cognitive Decline with Coronary and Arterial Calcification. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R. A look at the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease based on the brain ischemia model. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2024, 21, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Z.L.; Vaz, D.C.; Brito, R.M.M. Morphological and Molecular Profiling of Amyloid-β Species in Alzheimer’s Pathogenesis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 4391–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Ułamek, M.; Jabłoński, M. Alzheimer’s mechanisms in ischemic brain degeneration. Anat. Rec. 2009, 292, 1863–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Januszewski, S.; Czuczwar, S.J. Brain Ischemia as a Prelude to Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 636653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elman-Shina, K.; Efrati, S. Ischemia as a common trigger for Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1012779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecordier, S.; Pons, V.; Rivest, S.; ElAli, A. Multifocal Cerebral Microinfarcts Modulate Early Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology in a Sex-Dependent Manner. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 813536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluta, R. Brain ischemia as a bridge to Alzheimer’s disease. Neural. Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 791–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, T.K.; Ganesh, B.P.; Fatima-Shad, K. Common signaling pathways involved in Alzheimer’s disease and stroke: Two faces of the same coin. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2023, 7, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.Y.; Quan, M.; Wei, Y.; Wang, W.; Xu, L.; Wang, Q.; Jia, J. Critical thinking of Alzheimer’s transgenic mouse model: Current research and future perspective. Sci. China-Life Sci. 2023, 66, 2711–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R. Neuroinflammation in the Post-Ischemic Brain in the Presence of Amyloid and Tau Protein. Discov. Med. 2025, 37, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R. Direct and indirect role of non-coding RNAs in company with amyloid and tau protein in promoting neuroinflammation in post-ischemic brain neurodegeneration. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1670462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Srivastav, S.; Yadav, A.K.; Srikrishna, S.; Perry, G. Overview of Alzheimer’s disease and some therapeutic approaches targeting Aβ by using several synthetic and herbal compounds. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 7361613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasb, M.; Tao, W.; Chen, N. Alzheimer’s Disease Puzzle: Delving into Pathogenesis Hypotheses. Aging Dis. 2024, 15, 43–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarov, O.; Gupta, M.; Kumar, P.; Morrissey, Z.; Phan, T. Memory Circuits in Dementia: The Engram, Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Alzheimer’s Disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2024, 236, 102601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Li, Y.; Ye, K. Advancements and challenges in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 1152–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, M.S.; Guil-Guerrero, J.L.; Prates, J.A.M.; Lopes, P.A. Insights on the Use of Transgenic Mice Models in Alzheimer’s Disease Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, M.Z.; Peng, T.; Duarte, M.L.; Wang, M.; Cai, D. Updates on mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, R.J.; Jamshidi, P.; Plascencia-Villa, G.; Perry, G. The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis: A Conclusion in Search of Support. Am. J. Pathol. 2025, 195, 1988–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arruda, B.P.; Martins, P.P.; Kihara, A.H.; Takada, S.H. Perinatal asphyxia and Alzheimer’s disease: Is there a correlation? Front. Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1567719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J. Alzheimer’s Disease: Treatment Challenges for the Future. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Kida, E.; Lossinsky, A.S.; Golabek, A.A.; Mossakowski, M.J.; Wisniewski, H.M. Complete cerebral ischemia with short-term survival in rats induced by cardiac arrest. I. Extracellular accumulation of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid protein precursor in the brain. Brain Res. 1994, 649, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Barcikowska, M.; Debicki, G.; Ryba, M.; Januszewski, S. Changes in amyloid precursor protein and apolipoprotein E immunoreactivity following ischemic brain injury in rat with long-term survival: Influence of idebenone treatment. Neurosci. Lett. 1997, 232, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Groen, T.; Puurunen, K.; Mäki, H.M.; Sivenius, J.; Jolkkonen, J. Transformation of diffuse beta-amyloid precursor protein and beta-amyloid deposits to plaques in the thalamus after transient occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in rats. Stroke 2005, 36, 1551–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.P.; Wu, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.D.; Chen, Y.X.; Gu, Y.H.; Liu, T. Cerebral ischemia and Alzheimer’s disease: The expression of amyloid-beta and apolipoprotein E in human hippocampus. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2007, 12, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracko, O.; Njiru, B.N.; Swallow, M.; Ali, M.; Haft-Javaherian, M.; Schaffer, C.B. Increasing cerebral blood flow improves cognition into late stages in Alzheimer’s disease mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2020, 40, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis, E.; Hascup, K.N.; Hascup, E.R. Alzheimer’s disease: The link between amyloid-β and neurovascular dysfunction. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 76, 1179–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, T.; Hirano, A.; Katagiri, T.; Sasaki, H.; Yamada, S. Neurofibrillary tangle formation in the nucleus basalis of Meynert ipsilateral to a massive cerebral infarct. Ann. Neurol. 1988, 23, 620–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatsuta, H.; Takao, M.; Nogami, A.; Uchino, A.; Sumikura, H.; Takata, T.; Morimoto, S.; Kanemaru, K.; Adachi, T.; Arai, T.; et al. Tau and TDP-43 accumulation of the basal nucleus of Meynert in individuals with cerebral lobar infarcts or hemorrhage. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2019, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.A.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, K.J.; Ahn, K.J. Hypoperfusion and ischemia in cerebral amyloid angiopathy documented by 99mTc-ECD brain perfusion SPECT. J. Nucl. Med. 2009, 50, 1969–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Miziak, B.; Czuczwar, S.J. Post-ischemic permeability of the blood–brain barrier to amyloid and platelets as a factor in the maturation of Alzheimer’s disease-type brain neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Kiś, J.; Januszewski, S.; Jabłoński, M.; Czuczwar, S.J. Cross-Talk between Amyloid, Tau Protein and Free Radicals in Post-Ischemic Brain Neurodegeneration in the Form of Alzheimer’s Disease Proteinopathy. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Shan, X.; Men, W.; Zhai, H.; Qiao, X.; Geng, L.; Li, C. The effect of crocin on memory, hippocampal acetylcholine level, and apoptosis in a rat model of cerebral ischemia. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 130, 110543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, S.; Ren, T.; BoYang Yan, B.Y. Effects of curcumin on memory, hippocampal acetylcholine level and neuroapoptosis in repeated cerebral ischemia rat model. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 36, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R. The role of apolipoprotein E in the deposition of beta-amyloid peptide during ischemia-reperfusion brain injury. A model of early Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 903, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłoński, M.; Maciejewski, R.; Januszewski, S.; Ułamek, M.; Pluta, R. One year follow up in ischemic brain injury and the role of Alzheimer factors. Physiol. Res. 2011, 60, S113–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Tremblaye, P.B.; Plamondon, H. Impaired conditioned emotional response and object recognition are concomitant to neuronal damage in the amygdala and perirhinal cortex in middle-aged ischemic rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 219, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiryk, A.; Pluta, R.; Figiel, I.; Mikosz, M.; Ulamek, M.; Niewiadomska, G.; Jablonski, M.; Kaczmarek, L. Transient brain ischemia due to cardiac arrest causes irreversible long-lasting cognitive injury. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 219, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhang, M.; Fang, C.Q.; Zhou, H.D. Cerebral ischemia aggravates cognitive impairment in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Life Sci. 2011, 89, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohan, C.H.; Neumann, J.T.; Dave, K.R.; Alekseyenko, A.; Binkert, M.; Stransky, K.; Lin, H.W.; Barnes, C.A.; Wright, C.B.; Perez-Pinzon, M.A. Effect of cardiac arrest on cognitive impairment and hippocampal plasticity in middle-aged rats. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Gupta, V.K.; Wu, Y.; Pushpitha, K.; Chitranshi, N.; Gupta, V.B.; Fitzhenry, M.J.; Moghaddam, M.Z.; Karl, T.; Salekdeh, G.H.; et al. Mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease demonstrates differential effects of early disease pathology on various brain regions. Proteomics 2021, 21, e2000213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endres, K. Apolipoprotein A1, the neglected relative of Apolipoprotein E and its potential role in Alzheimer’s disease. Neural. Regen. Res. 2021, 16, 2141–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raulin, A.C.; Martens, Y.A.; Bu, G. Lipoproteins in the Central Nervous System: From Biology to Pathobiology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2022, 91, 731–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Noorani, A.; Sun, Y.; Michikawa, M.; Zou, K. Multi-functional role of apolipoprotein E in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1535280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnathambi, S.; Adityan, A.; Chidambaram, H.; Chandrashekar, M. Apolipoprotein E and Tau interaction in Alzheimer’s disease. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2025, 147, 375–400. [Google Scholar]

- Juul Rasmussen, I.; Luo, J.; Frikke-Schmidt, R. Lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins: Associations with cognition and dementia. Atherosclerosis 2024, 398, 118614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Kocki, J.; Bogucki, J.; Bogucka-Kocka, A.; Czuczwar, S.J. Apolipoprotein (APOA1, APOE, CLU) genes expression in the CA3 region of the hippocampus in an ischemic model of Alzheimer’s disease with survival up to 2 years. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 103, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalani, R.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Deepa, D.; Gopala, S.; Prabhakaran, D.; Tirschwell, D.; Sylaja, P.N. Apolipoproteins B and A1 in Ischemic Stroke Subtypes. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 29, 104670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhea, E.M.; Banks, W.A. Interactions of lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins with the blood–brain barrier. Pharm. Res. 2021, 38, 1469–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etuze, T.; Triniac, H.; Zheng, Z.; Vivien, D.; Dubois, F. Apolipoproteins in ischemic stroke progression and recovery: Key molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Neurobiol. Dis. 2025, 209, 106896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kida, E.; Pluta, R.; Lossinsky, A.S.; Golabek, A.A.; Choi-Miura, N.H.; Wisniewski, H.M.; Mossakowski, M.J. Complete cerebral ischemia with short-term survival in rat induced by cardiac arrest. II. Extracellular and intracellular accumulation of apolipoproteins E and J in the brain. Brain Res. 1995, 674, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemello, K.; Guedon, A.F.; Techer, R.; Jaafar, A.K.; Guilhen, S.; Swietek, M.J.; Lambert, G.; Gallo, A. Apolipoprotein E Plasma Concentrations Are Predictive of Recurrent Strokes: Insights From the SPARCL Trial. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2025, 14, e036630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; Jiang, F.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Jia, R.; Liu, M.; Hu, J. The hypoperfusion intensity ratio associates with APOE gene polymorphism in acute ischemic stroke patients with large vessel occlusion. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, Z.; Wen, Y.; Guo, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, D.; Li, L.; Liu, H. Apolipoprotein A1 and Lipoprotein(a) as Biomarkers for the “Penumbra Freezing” in Acute Ischemic Stroke: Insights From a Case-Control and Mendelian Randomization Study. Curr. Med. Chem. 2025. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Kocki, J.; Bogucka-Kocka, A.; Bogucki, J.; Czuczwar, S.J. Alterations of Mitophagy (BNIP3), Apoptosis (CASP3), and Autophagy (BECN1) Genes in the Frontal Cortex in an Ischemic Model of Alzheimer’s Disease with Long-Term Survival. Curr. Alzheimer’s Res. 2025, 22, 442–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajha, H.E.; Hassanein, A.; Mesilhy, R.; Nurulhaque, Z.; Elghoul, N.; Burgon, P.G.; Al Saady, R.M.; Pedersen, S. Apolipoprotein A (ApoA) in Neurological Disorders: Connections and Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccone, L.; Shi, C.; di Lorenzo, D.; Van Baelen, A.C.; Tonali, N. The Positive Side of the Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid Cross-Interactions: The Case of the Abeta 1-42 Peptide with Tau, TTR, CysC, and ApoA1. Molecules 2020, 25, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rost, N.S.; Brodtmann, A.; Pase, M.P.; van Veluw, S.J.; Biffi, A.; Duering, M.; Hinman, J.D.; Dichgans, M. Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 1252–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Button, E.B.; Boyce, G.K.; Wilkinson, A.; Stukas, S.; Hayat, A.; Fan, J.; Wadsworth, B.J.; Robert, J.; Martens, K.M.; Wellington, C.L. ApoA-I deficiency increases cortical amyloid deposition, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cortical and hippocampal astrogliosis, and amyloid-associated astrocyte reactivity in APP/PS1 mice. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Magro, R.; Simonelli, S.; Cox, A.; Formicola, B.; Corti, R.; Cassina, V.; Nardo, L.; Mantegazza, F.; Salerno, D.; Grasso, G.; et al. The Extent of Human Apolipoprotein A-I Lipidation Strongly Affects the β-Amyloid Effux Across the Blood–brain barrier in vitro. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefterov, I.; Fitz, N.F.; Cronican, A.A.; Fogg, A.; Lefterov, P.; Kodali, R.; Wetzel, R.; Koldamova, R. Apolipoprotein A-I Deficiency Increases Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy and Cognitive Deficits in APP/PS1DE9 Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 36945–36957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldamova, R.P.; Lefterov, I.M.; Lefterova, M.I.; Lazo, J.S. Apolipoprotein A-I Directly Interacts with Amyloid Precursor Protein and Inhibits Aβ Aggregation and Toxicity. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 3553–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula-Lima, A.C.; Tricerri, M.A.; Brito-Moreira, J.; Bomfim, T.R.; Oliveira, F.F.; Magdesian, M.H.; Grinberg, L.T.; Panizzutti, R.; Ferreira, S.T. Human apolipoprotein A–I binds amyloid- and prevents A-induced neurotoxicity. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de Retana, S.; Montañola, A.; Marazuela, P.; De La Cuesta, M.; Batlle, A.; Fatar, M.; Grudzenski, S.; Montaner, J.; Hernández-Guillamon, M. Intravenous treatment with human recombinant ApoA-I Milano reduces beta amyloid cerebral deposition in the APP23-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2017, 60, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merched, A.; Xia, Y.; Visvikis, S.; Serot, J.M.; Siest, G. Decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and serum apolipoprotein AI concentrations are highly correlated with the severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2000, 21, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saczynski, J.S.; White, L.; Peila, R.L.; Rodriguez, B.L.; Launer, L.J. The Relation between Apolipoprotein A-I and Dementia. The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 165, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitz, N.F.; Tapias, V.; Cronican, A.A.; Castranio, E.L.; Saleem, M.; Carter, A.Y.; Lefterova, M.; Lefterov, I.; Koldamova, R. Opposing effects of Apoe/Apoa1 double deletion on amyloid-β pathology and cognitive performance in APP mice. Brain 2015, 138, 3699–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solé, M.; Marazuela, P.; Castellote, L.; Bonaterra-Pastra, A.; Giménez-Llort, L.; Hernández-Guillamon, M. Therapeutic effect of human ApoA-I-Milano variant in aged transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 180, 1999–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahan, T.E.; Wang, C.; Bao, X.; Choudhury, A.; Ulrich, J.D.; Holtzman, D.M. Selective reduction of astrocyte apoE3 and apoE4 strongly reduces Aβ accumulation and plaque-related pathology in a mouse model of amyloidosis. Mol. Neurodegener. 2022, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, S.; Easterbrook-Smith, S.B.; Rybchyn, M.S.; Carver, J.A.; Wilson, M.R. Clusterin is an ATP-independent chaperone with very broad substrate specificity that stabilizes stressed proteins in folding competent state. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 15953–15960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herring, S.K.; Moon, H.-J.; Rawal, P.; Chhibber, A.; Zhao, L. Brain clusterin protein isoforms and mitochondrial localization. Elife 2019, 18, e48255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.D.; Sagare, A.P.; Friedman, A.E.; Bedi, G.S.; Holtzman, D.M.; Deane, R.; Zlokovic, B.V. Transport pathways for clearance of human Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide and apolipoproteins E and J in the mouse central nervous system. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2007, 27, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtas, A.M.; Kang, S.S.; Olley, B.M.; Gatherer, M.; Shinohara, M.; Lozano, P.A.; Liu, C.C.; Kurti, A.; Baker, K.E.; Dickson, D.W.; et al. Loss of clusterin shifts amyloid deposition to the cerebrovasculature via disruption of perivascular drainage pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E6962–E6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Lossinsky, A.S.; Wiśniewski, H.M.; Mossakowski, M.J. Early blood–brain barrier changes in the rat following transient complete cerebral ischemia induced by cardiac arrest. Brain Res. 1994, 633, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Januszewski, S.; Ułamek, M. Ischemic blood–brain barrier and amyloid in white matter as etiological factors in leukoaraiosis. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2008, 102, 353–356. [Google Scholar]

- Sekeljic, V.; Bataveljic, D.; Stamenkovic, S.; Ułamek, M.; Jabłoński, M.; Radenovic, L.; Pluta, R.; Andjus, P.R. Cellular markers of neuroinflammation and neurogenesis after ischemic brain injury in the long-term survival rat model. Brain Struct. Funct. 2012, 217, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radenovic, L.; Nenadic, M.; Ułamek-Kozioł, M.; Januszewski, S.; Czuczwar, S.J.; Andjus, P.R.; Pluta, R. Heterogeneity in brain distribution of activated microglia and astrocytes in a rat ischemic model of Alzheimer’s disease after 2 years of survival. Aging 2020, 12, 12251–12267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiggins, A.K.; Shen, P.-J.; Gundlach, A.L. Delayed, but prolonged increases in astrocytic clusterin (ApoJ) mRNA expression following acute cortical spreading depression in the rat: Evidence for a role of clusterin in ischemic tolerance. Mol. Brain Res. 2003, 114, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Chen, Z.; Shui, W. Clusterin: Structure, function and roles in disease. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 22, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.H.; DeMattos, R.B.; Dugan, L.L.; Kim-Han, J.S.; Brendza, R.P.; Fryer, J.D.; Kierson, M.; Cirrito, J.; Quick, K.; Harmony, J.A.; et al. Clusterin contributes to caspase-3-independent brain injury following neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, C.E.; Affleck, A.J.; Bahar, A.Y.; Carew-Jones, F.; Halliday, G.M. Intracellular and secreted forms of clusterin are elevated early in Alzheimer’s disease and associate with both Aβ and tau pathology. Neurobiol. Aging 2020, 89, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Che, R.; Liang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Han, C.; Lu, H.; Song, W.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z. Clusterin transduces Alzheimer-risk signals to amyloidogenesis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palihati, N.; Tang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Yu, D.; Liu, G.; Quan, Z.; Ni, J.; Yan, Y.; Qing, H. Clusterin is a Potential Therapeutic Target in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 3836–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuste-Checa, P.; Trinkaus, V.A.; Riera-Tur, I.; Imamoglu, R.; Schaller, T.F.; Wang, H.; Dudanova, I.; Hipp, M.S.; Bracher, A.; Hartl, F.U. The extracellular chaperone Clusterin enhances Tau aggregate seeding in a cellular model. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Lossinsky, A.S.; Mossakowski, M.J.; Faso, L.; Wisniewski, H.M. Reassessment of a new model of complete cerebral ischemia in rats. Method of induction of clinical death, pathophysiology and cerebrovascular pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 1991, 83, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocki, J.; Ułamek-Kozioł, M.; Bogucka-Kocka, A.; Januszewski, S.; Jabłoński, M.; Gil-Kulik, P.; Brzozowska, J.; Petniak, A.; Furmaga-Jabłońska, W.; Bogucki, J.; et al. Dysregulation of Amyloid-β Protein Precursor, β-Secretase, Presenilin 1 and 2 Genes in the Rat Selectively Vulnerable CA1 Subfield of Hippocampus Following Transient Global Brain Ischemia. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015, 47, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Czuczwar, S.J. Ischemia-reperfusion programming of Alzheimer’s disease-related genes—A new perspective on brain neurodegeneration after cardiac arrest. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Bogucka-Kocka, A.; Kocki, J.; Bogucki, J.; Czuczwar, S.J. Tau Protein, α-synuclein, and Amyloid Precursor Protein Processing Genes in the Frontal Cortex of an Ischemic Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2026, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Pluta, R.; Kocki, J.; Bogucki, J.; Bogucka-Kocka, A.; Czuczwar, S.J. LRP1 And RAGE genes transporting amyloid and tau protein in the hippocampal CA3 area in an ischemic model of Alzheimer’s disease with 2-year survival. Cells 2023, 12, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babusikova, E.; Dobrota, D.; Turner, A.J.; Nalivaeva, N.N. Effect of global brain ischemia on amyloid precursor protein metabolism and expression of amyloid-degrading enzymes in rat cortex: Role in pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry 2021, 86, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, T.G.; Ignat, B.E.; Grosu, C.; Costache, A.D.; Leon, M.M.; Mitu, F. Lipid-derived biomarkers as therapeutic targets for chronic coronary syndrome and ischemic stroke: An updated narrative review. Medicina 2024, 60, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhani, D.W.; Rogers, D.P.; Engler, J.A.; Brouillette, C.G. Crystal structure of truncated human apolipoprotein A-I suggests a lipid-bound conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 12291–12296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milinkeviciute, G.; Green, K.N. Clusterin/apolipoprotein J, its isoforms and Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1167886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pluta, R.; Ułamek-Kozioł, M.; Kocki, J.; Bogucka-Kocka, A.; Bogucki, J.; Czuczwar, S.J. Alterations of Apolipoprotein A1, E, and J Genes in the Frontal Cortex in an Ischemic Model of Alzheimer’s Disease with 2-Year Survival. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010326

Pluta R, Ułamek-Kozioł M, Kocki J, Bogucka-Kocka A, Bogucki J, Czuczwar SJ. Alterations of Apolipoprotein A1, E, and J Genes in the Frontal Cortex in an Ischemic Model of Alzheimer’s Disease with 2-Year Survival. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010326

Chicago/Turabian StylePluta, Ryszard, Marzena Ułamek-Kozioł, Janusz Kocki, Anna Bogucka-Kocka, Jacek Bogucki, and Stanisław J. Czuczwar. 2026. "Alterations of Apolipoprotein A1, E, and J Genes in the Frontal Cortex in an Ischemic Model of Alzheimer’s Disease with 2-Year Survival" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010326

APA StylePluta, R., Ułamek-Kozioł, M., Kocki, J., Bogucka-Kocka, A., Bogucki, J., & Czuczwar, S. J. (2026). Alterations of Apolipoprotein A1, E, and J Genes in the Frontal Cortex in an Ischemic Model of Alzheimer’s Disease with 2-Year Survival. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010326