Integration of Non-Invasive Micro-Test Technology and 15N Tracing Reveals the Impact of Nitrogen Forms at Different Concentrations on Respiratory and Primary Metabolism in Glycyrrhiza uralensis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

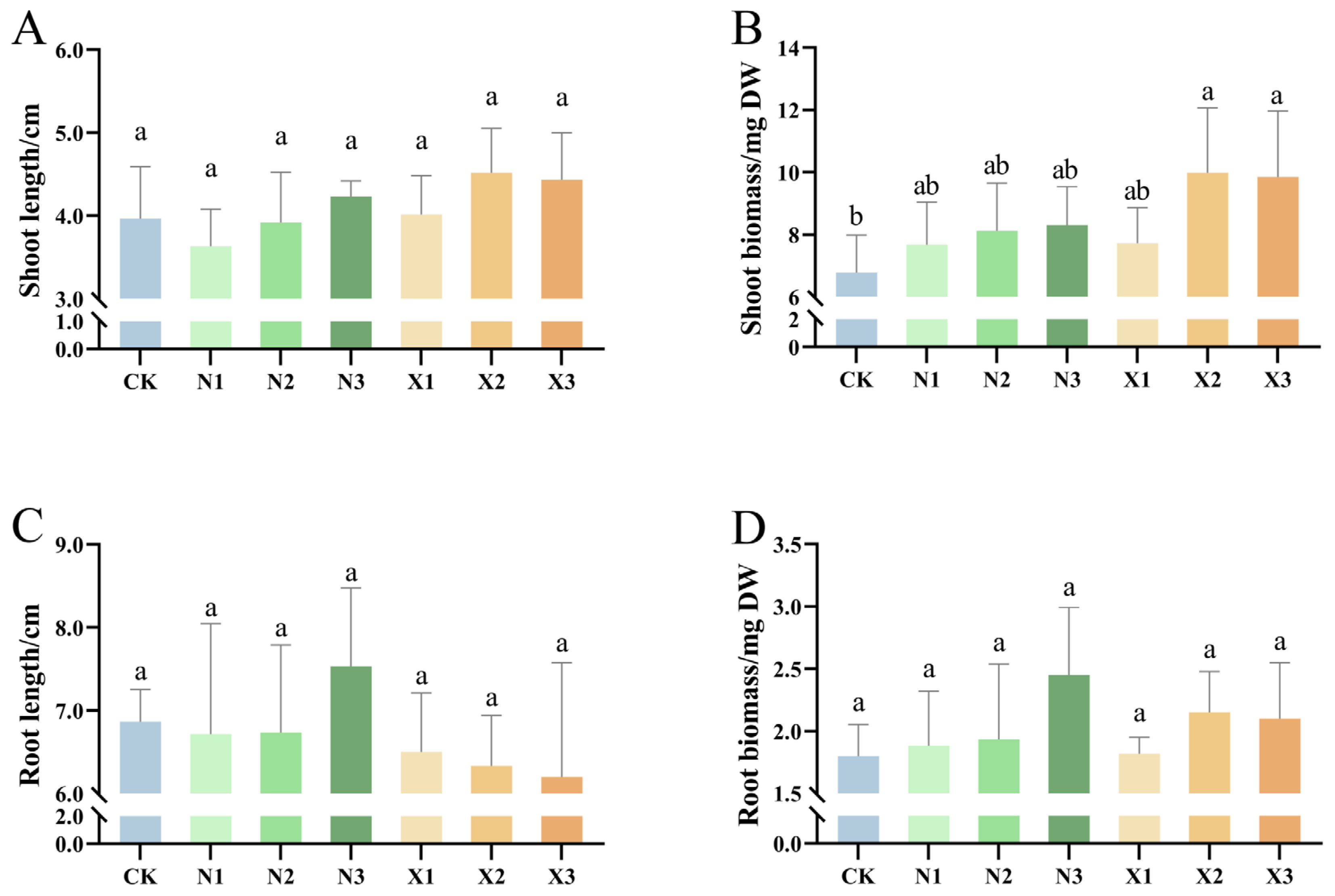

2.1. Growth Characteristics of G. uralensis Under Different Nitrogen Sources

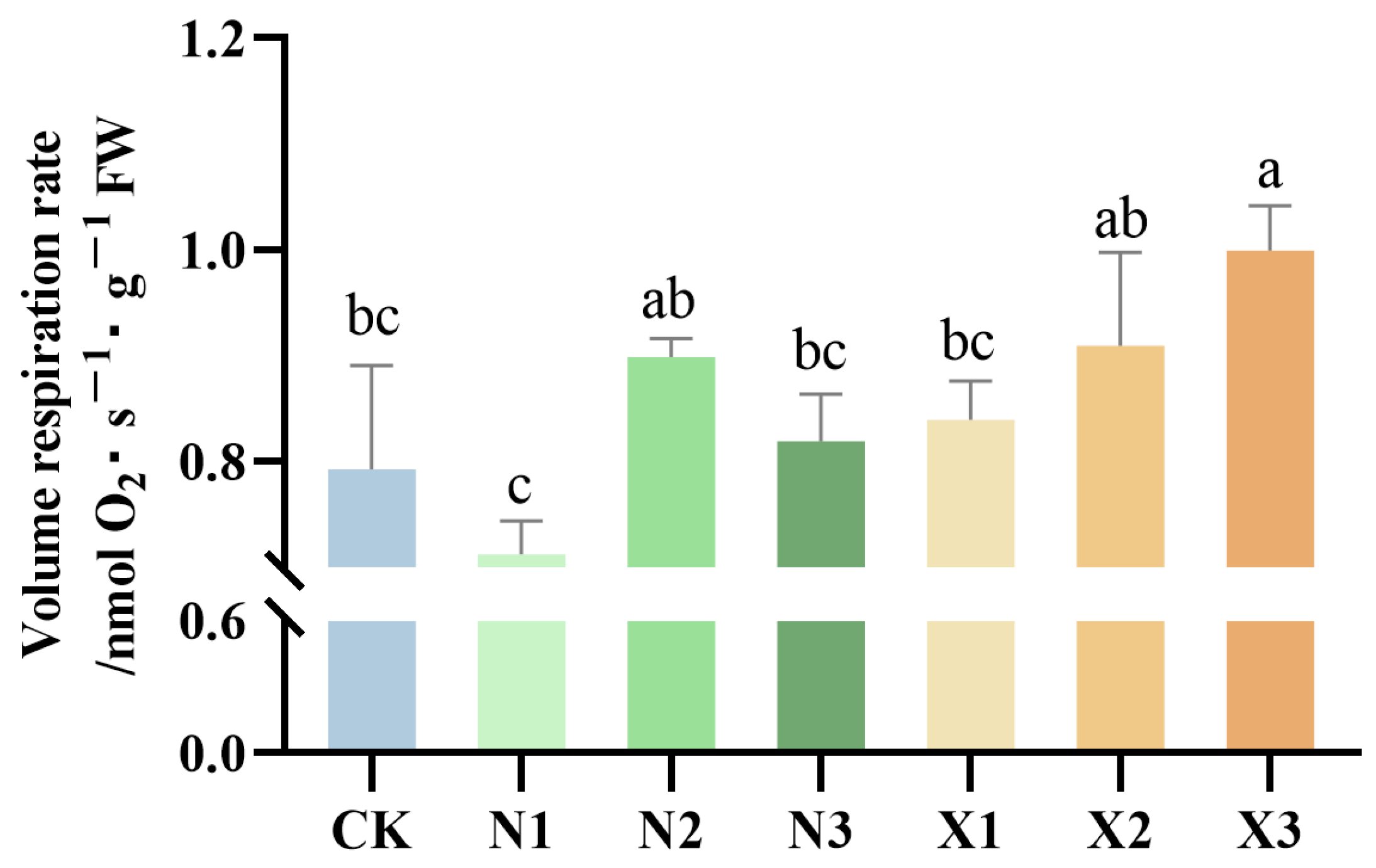

2.2. Changes in Root Respiration

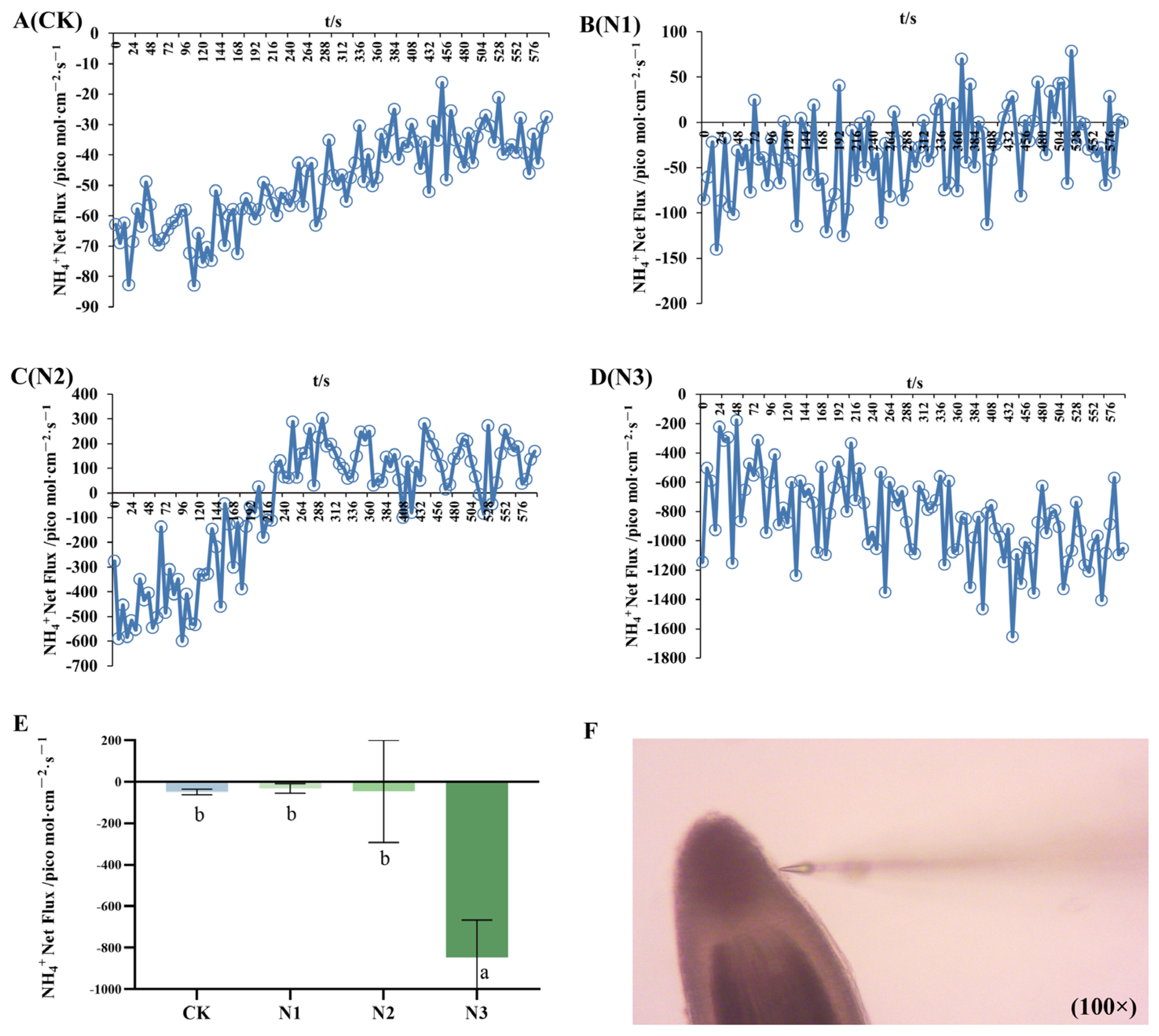

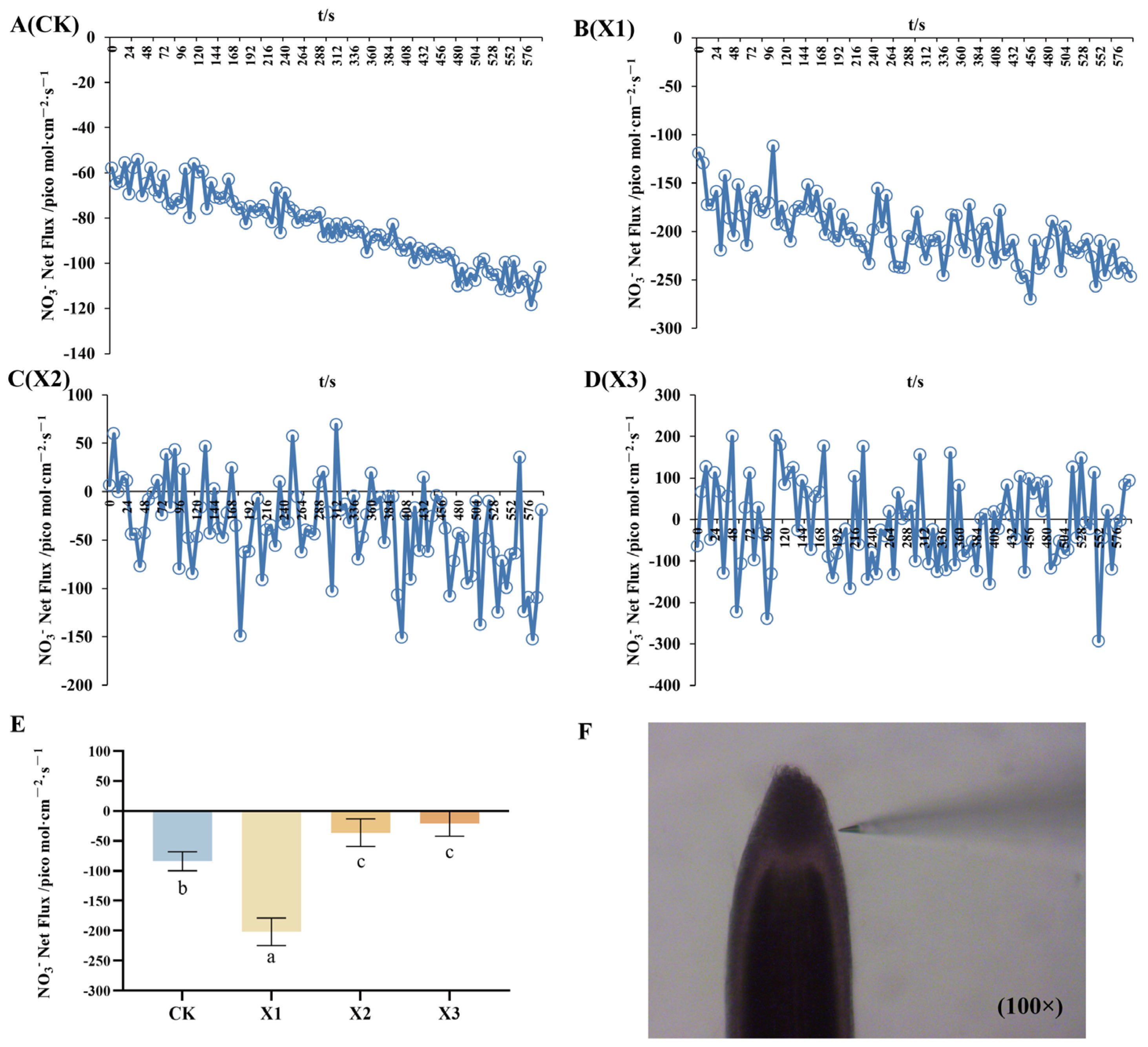

2.3. Net Fluxes of NH4+ and NO3−

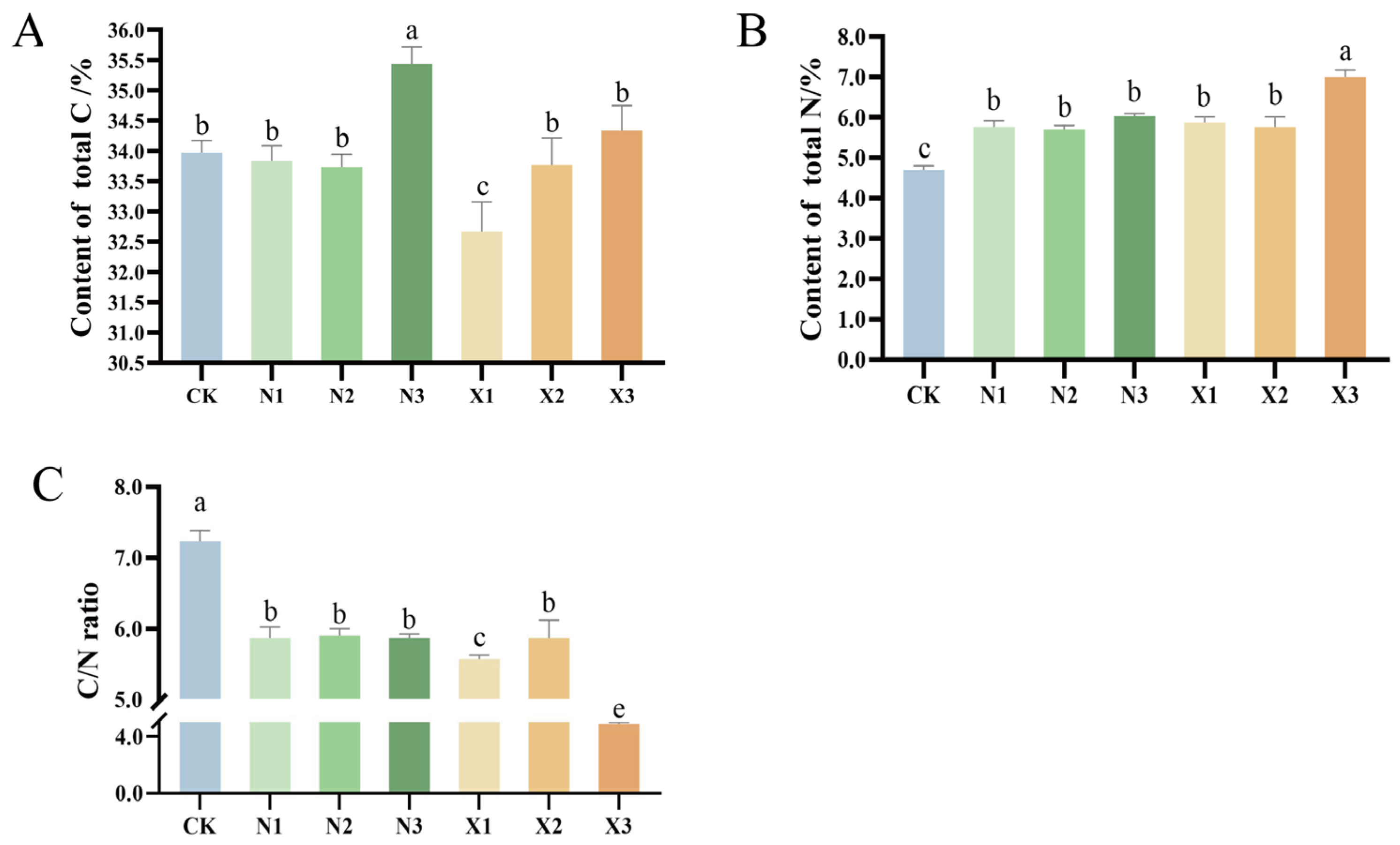

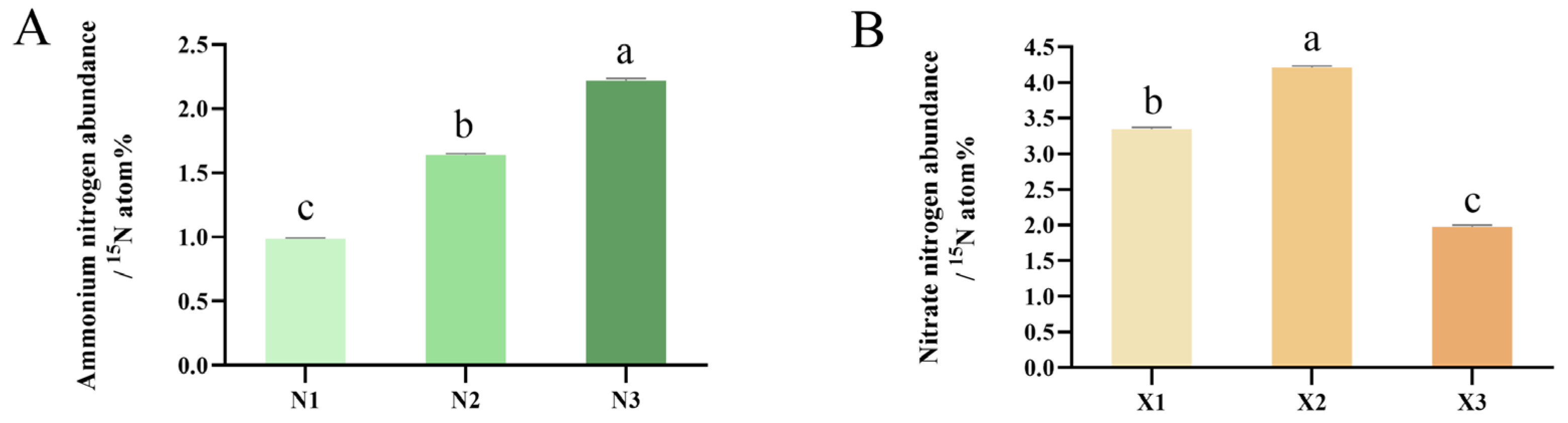

2.4. Contents of Total N, Total C, and δ15N

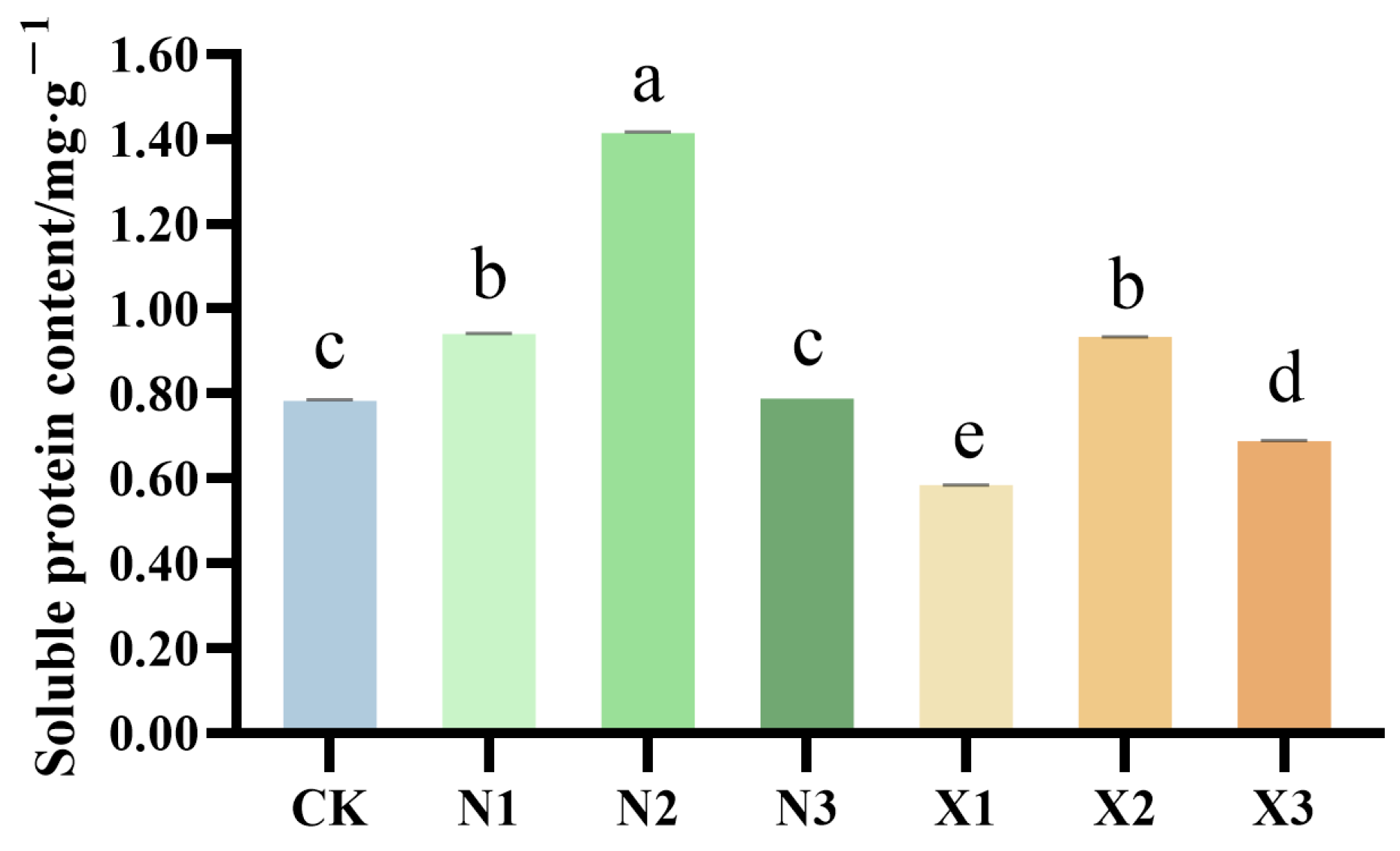

2.5. Total Proteins of G. uralensis Supplied Under Different Nitrogen Sources

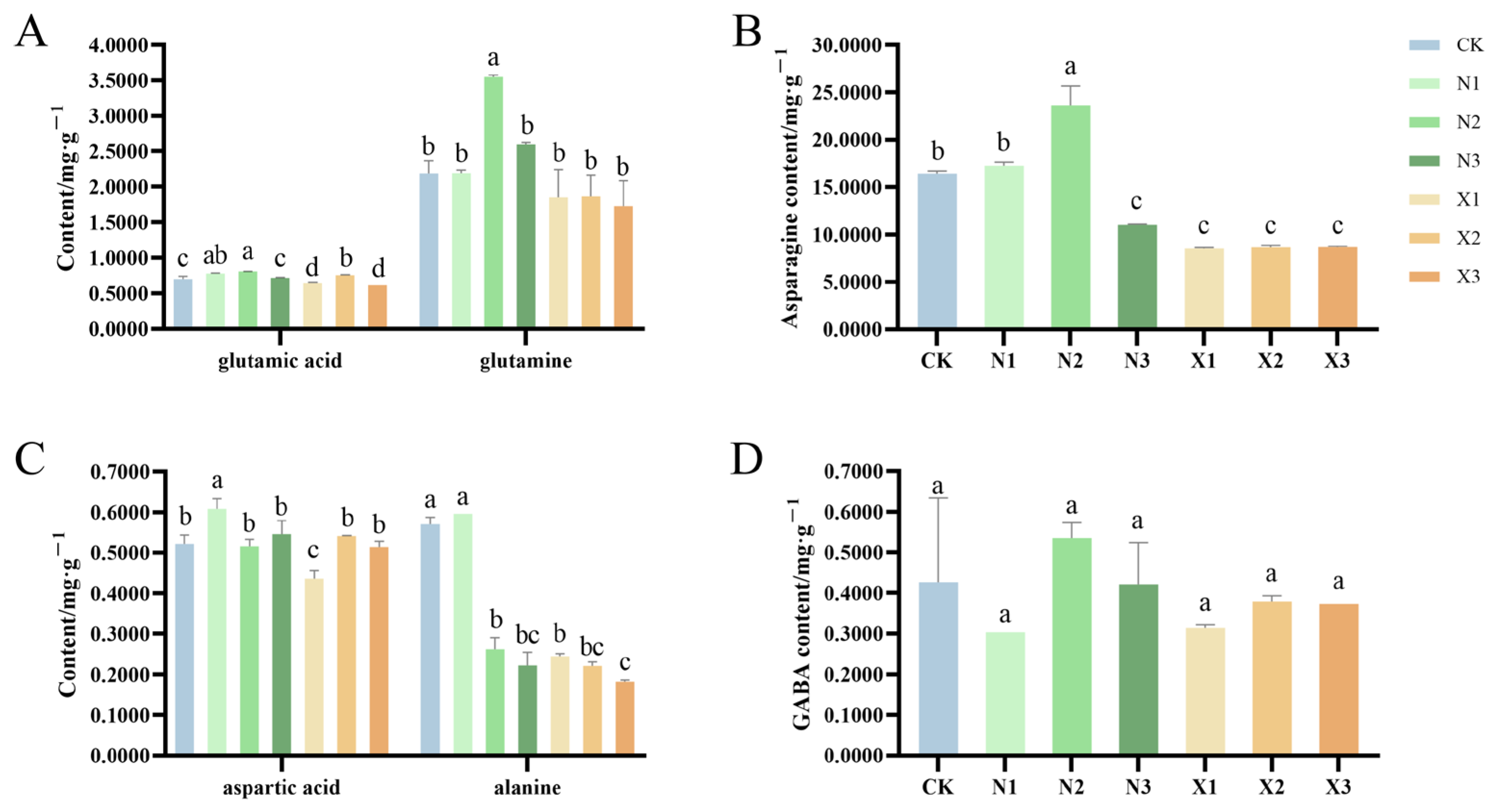

2.6. Amino Acid Contents of G. uralensis Under Different Nitrogen Treatments

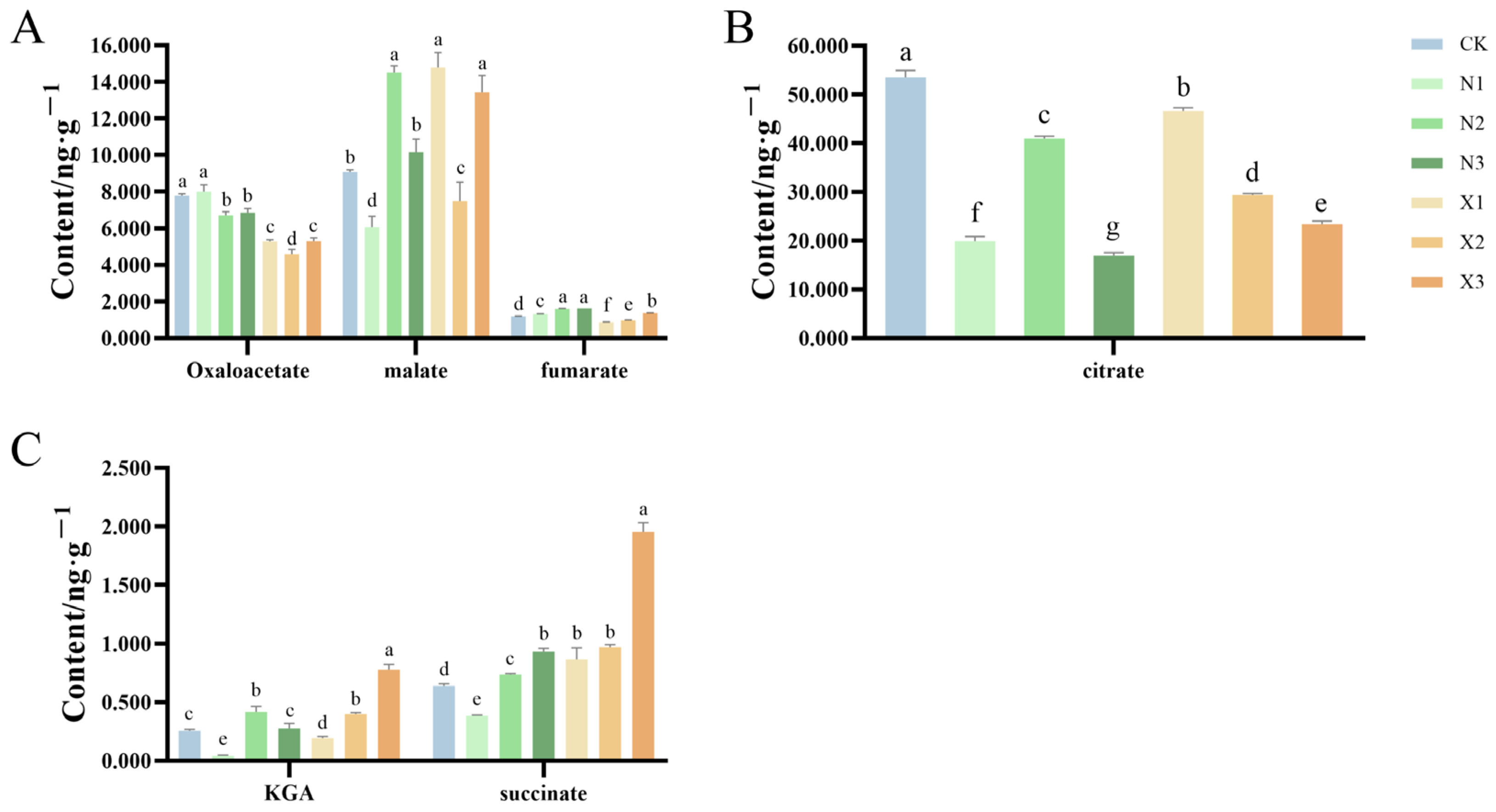

2.7. Organic Acids Content of G. uralensis Supplied with Different Nitrogen Sources

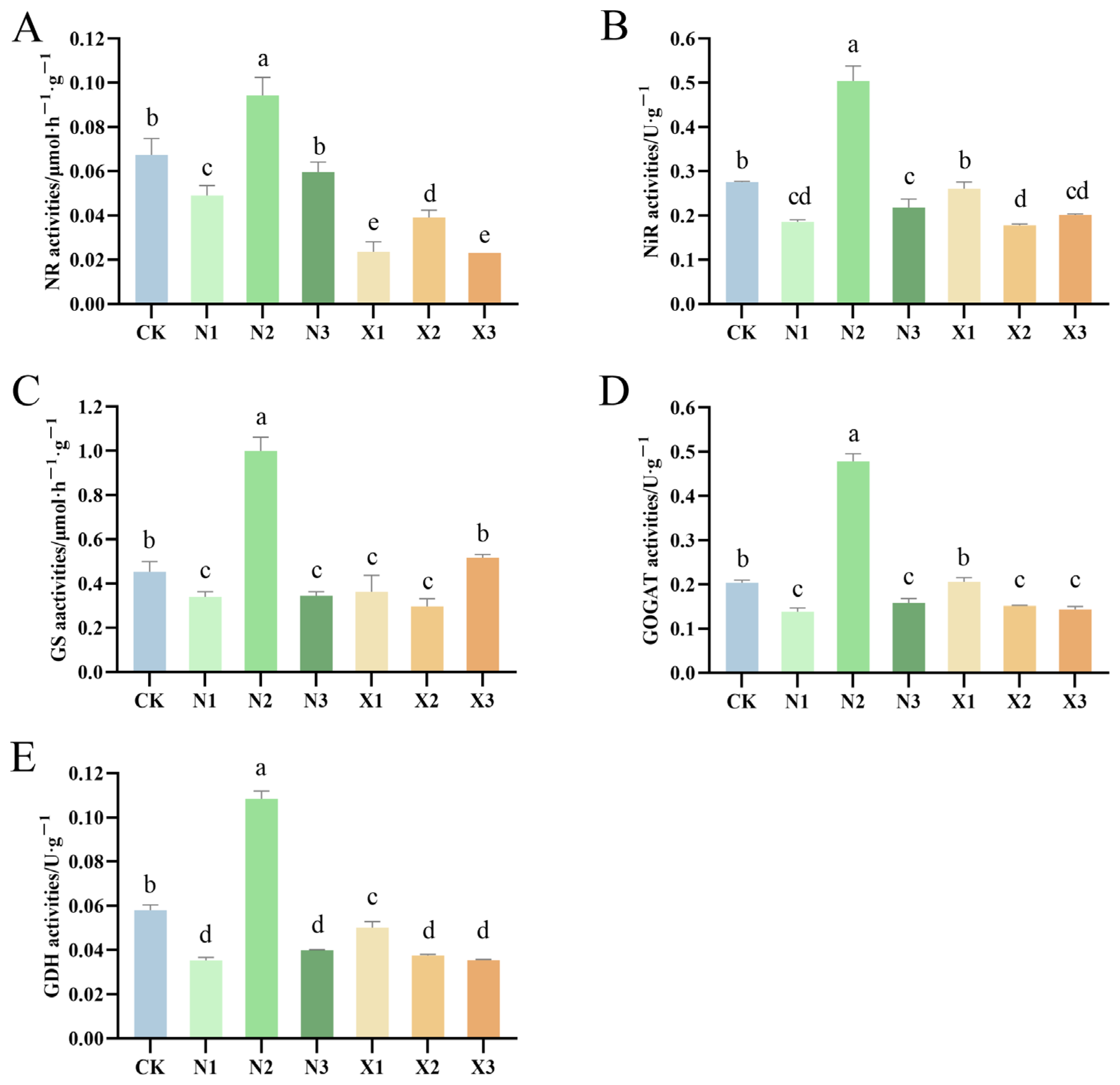

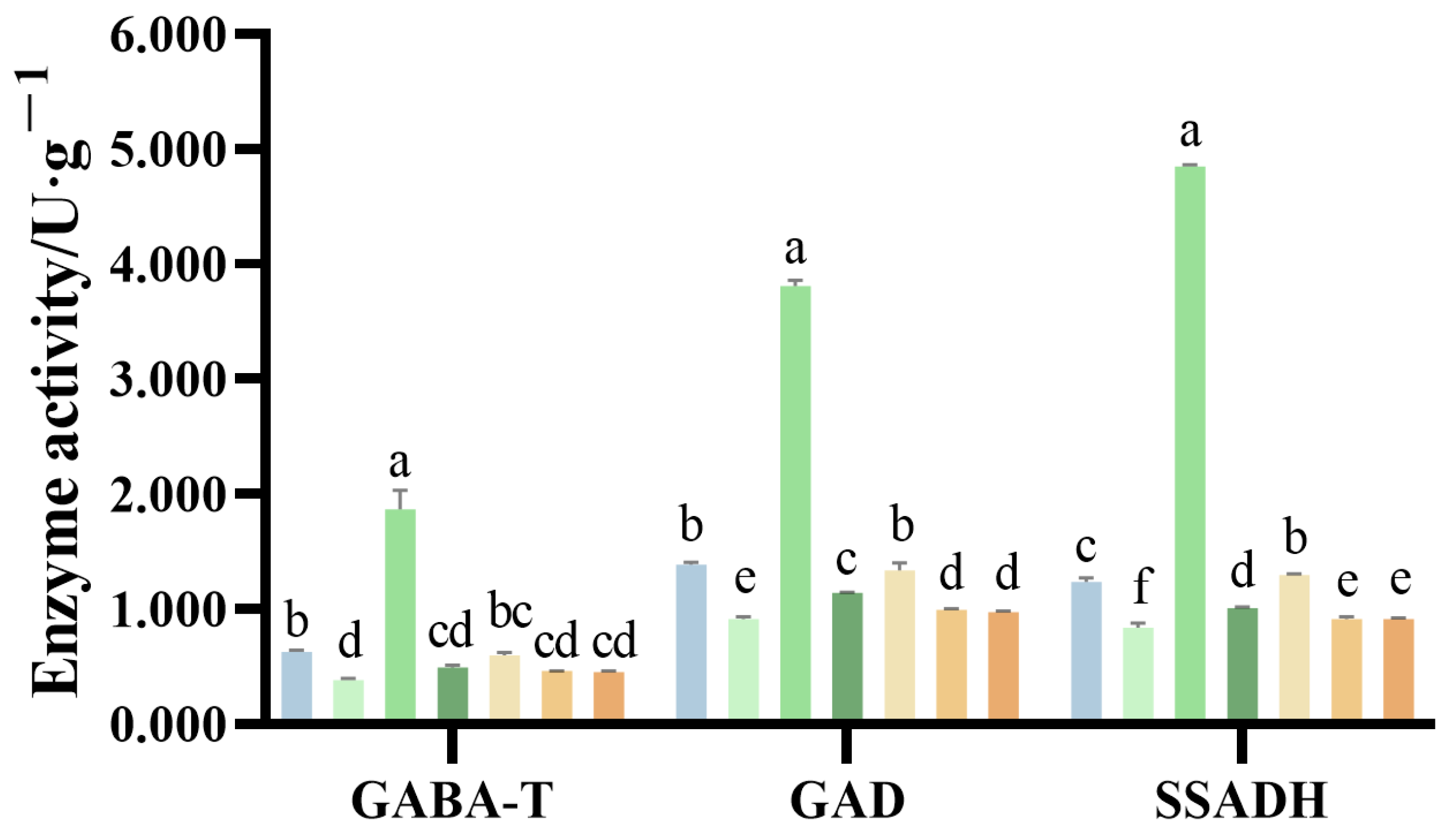

2.8. Activities of Enzymes Involved in N Metabolism of G. uralensis Supplied Under Different Nitrogen Sources

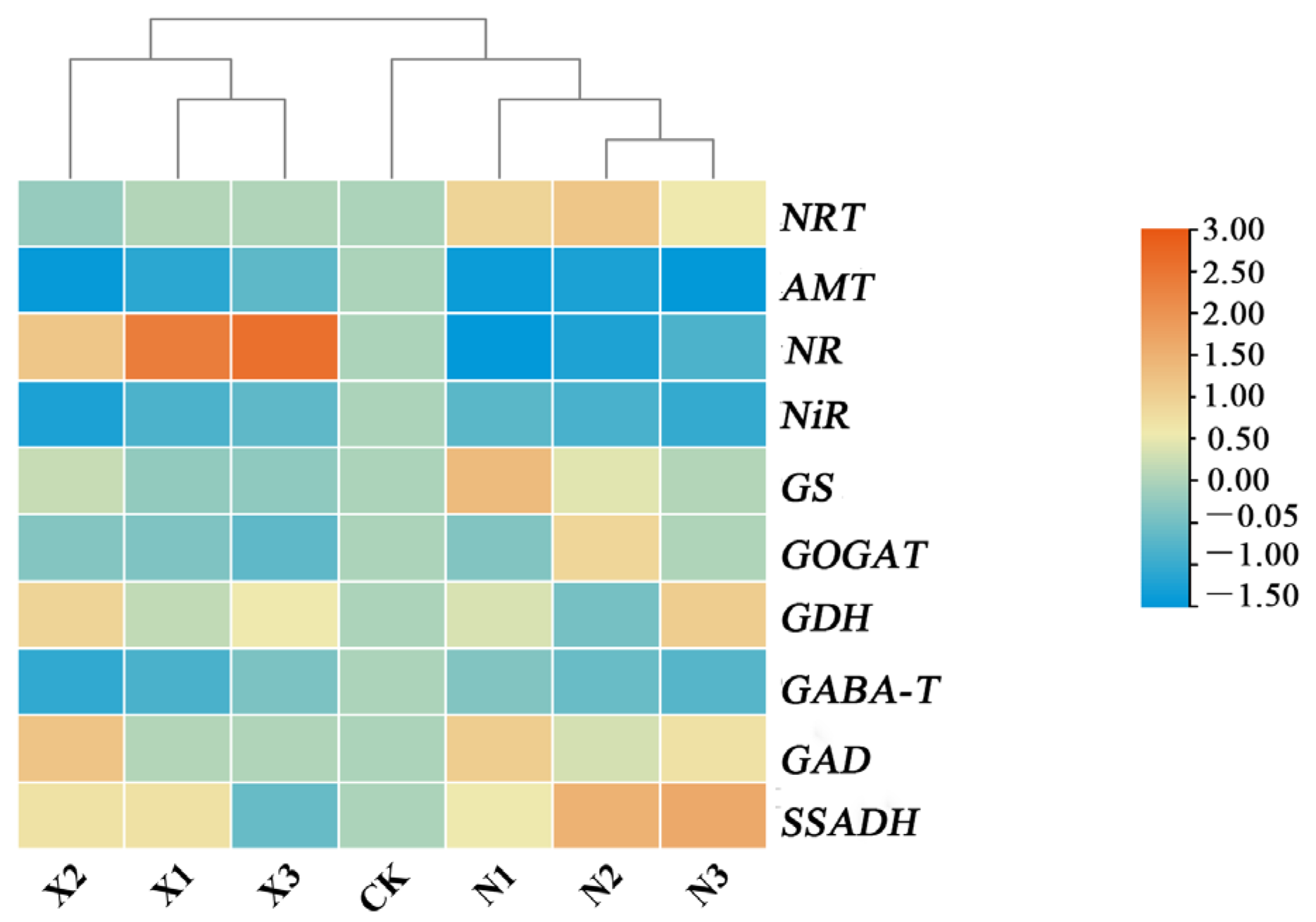

2.9. Transcript Levels of Key Genes Involved in N Metabolism of G. uralensis Supplied Under Different Nitrogen Sources

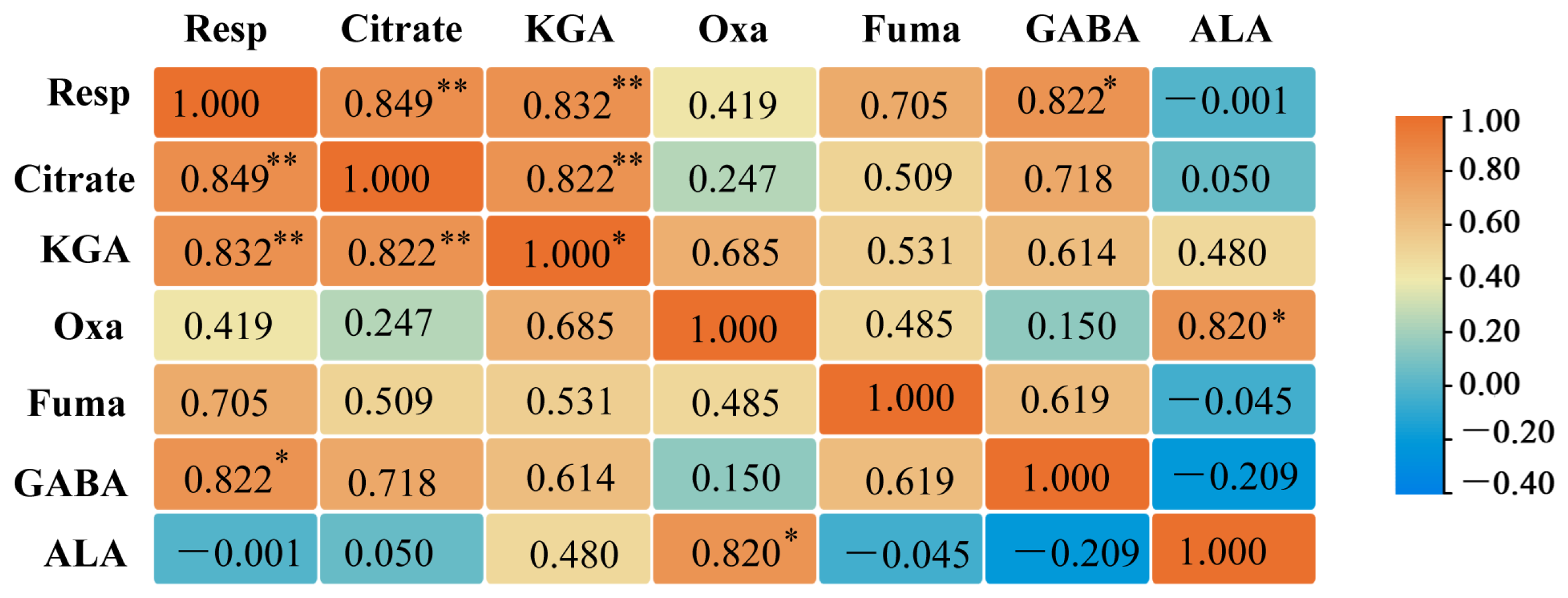

2.10. Correlation Analysis Between G. uralensis Respiratory and Primary Metabolism of Organic Acids and Amino Acids

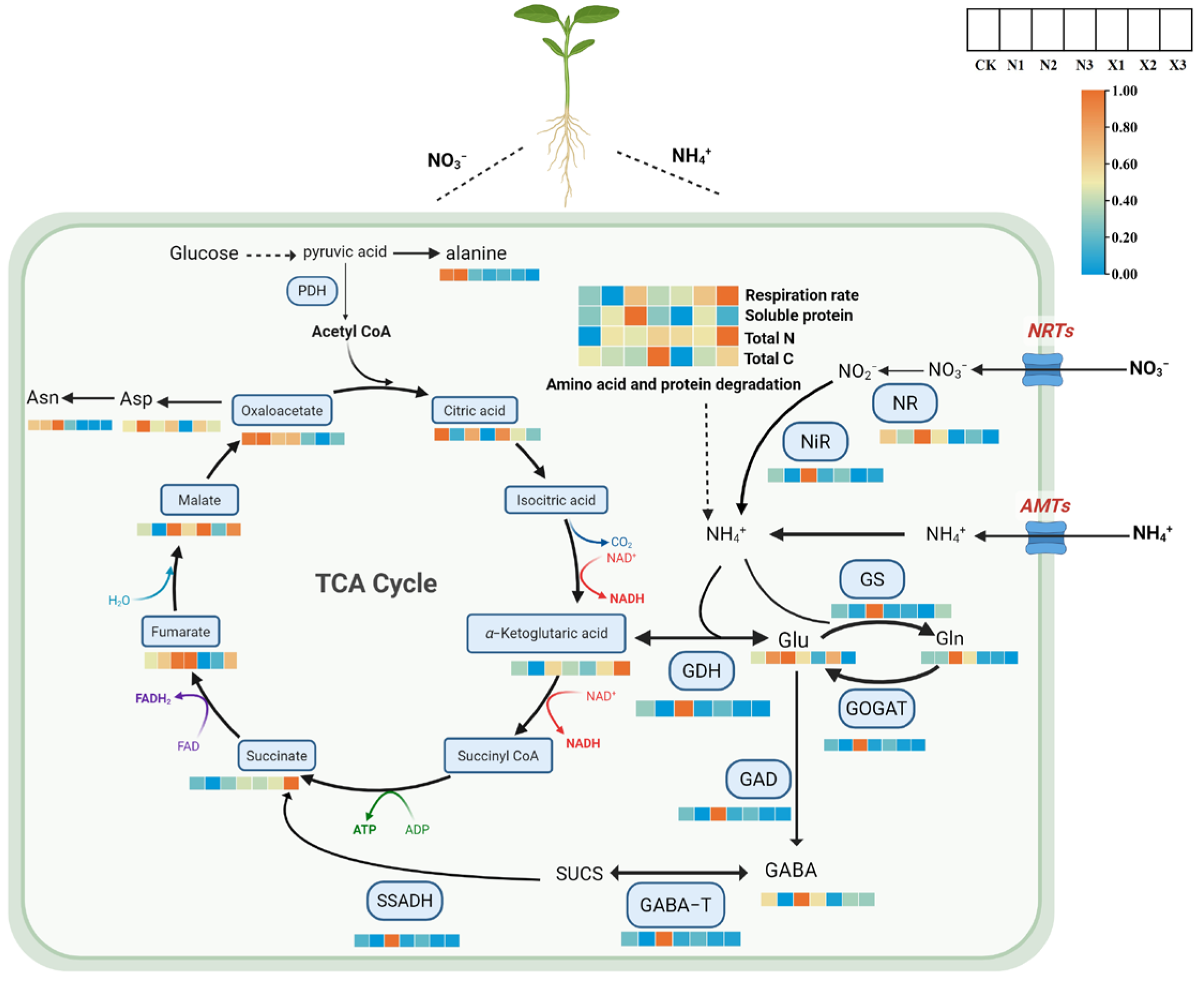

2.11. Joint Analysis of the Effects of Different Forms of Nitrogen on Respiratory and Metabolism in G. uralensis

3. Discussion

3.1. Nitrogen Absorption Characteristics and Their Relation to Nitrogen Metabolism Enzymes in G. uralensis

3.2. Utilization Characteristics of Ammonium and Nitrate Nitrogen in G. uralensis Roots

3.3. Relationship Between Nitrogen Absorption/Utilization and Respiratory Metabolism in G. uralensis

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Growth Conditions and Treatments

4.2. Measurement of Plant Biomass

4.3. Measurement of the Rate of Respiration

4.4. Determination of Net Fluxes of NH4+ and NO3−

4.5. Determination of Content of Total N, Total C, δ15N and Total Proteins

4.6. Determinations of Amino Acids, Organic Acids

4.7. Determinations of Activities of Enzymes Involved in N Metabolism

4.8. Analysis of the Transcript Levels of Key Genes Involved in N Metabolism

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NRT | Nitrate transporters |

| NR | Nitrate reductase |

| NiR | Nitrite reductase |

| GS | Glutamine synthetase |

| GOGAT | Glutamate synthetase |

| GDH | Glutamate dehydrogenase |

| AMTs | Ammonium transporters |

| Gln | Glutamine |

| Glu | Glutamic acid |

| KGA | α-ketoglutarate |

| TCA cycle | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| Oxa | Oxaloacetate |

| GABA | gamma-Aminobutyric acid |

| GAD | Glutamate decarboxylase |

| GABA-T | GABA transaminase |

| SUCS | Succinic semi-aldehyde |

| SSADH | Succinic semi-aldehyde dehydrogenase |

| PDH | Phosphofructokinase |

| Asn | Asparagine |

| Asp | Aspartic acid |

References

- Zhong, C.F.; Chen, C.Y.; Gao, X.; Tan, C.Y.; Bai, H.; Ning, K. Multi-omics profiling reveals comprehensive microbe-plant-metabolite regulation patterns for medicinal plant Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1874–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.L.; Zhu, L.; Ma, D.M.; Zhang, F.J.; Cai, Z.Y.; Bai, H.B.; Hui, J.; Li, S.H.; Xu, X.; Li, M. Integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics analyses highlight the flavonoid compounds response to alkaline salt stress in Glycyrrhiza uralensis Leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 5477–5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Ahmad, K.; Lim, J.H.; Ahmad, S.S.; Lee, E.J.; Choi, I. Biological insights and therapeutic potential of Glycyrrhiza uralensis and its bioactive compounds: An updated review. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2024, 47, 871–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.L.; Sun, Z.R.; Qu, J.X.; Yang, C.N.; Zhang, X.M.; Wei, X.X. Correlation between root respiration and the levels of biomass and glycyrrhizic acid in Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 2323–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Z.R.; Zhang, Y.F.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, S.T.; Wang, Y.J.; Sun, Z.R. Transcriptomics and metabolomics reveal the primary and secondary metabolism changes in Glycyrrhiza uralensis with different forms of nitrogen utilization. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnao, M.B.; Hernandez-Ruiz, J.; Cano, A. Role of melatonin and nitrogen metabolism in plants: Implications under nitrogen-excess or nitrogen-low. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldroyd, G.E.D.; Leyser, O. A plant’s diet, surviving in a variable nutrient environment. Science 2020, 368, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Wang, S.; Quan, J.N.; Su, W.L.; Lian, C.L.; Wang, D.L.; Xia, X.L.; Yin, W.L. Distinct carbon and nitrogen metabolism of two contrasting poplar species in response to different N supply levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Guan, L.K.; Zhang, C.T.; Zhang, S.Q.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Luo, J. Nitrogen assimilation genes in poplar: Potential targets for improving tree nitrogen use efficiency. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 216, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.P.; Zhao, J.C.; Feng, S.; Qiao, K.; Gong, S.F.; Wang, J.G.; Zhou, A.M. Heterologous expression of nitrate assimilation related-protein DsNAR2.1/NRT3.1 affects uptake of nitrate and ammonium in nitrogen-starved Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.B.; Wu, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Zhu, Q.G.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.Y.; Liu, G.; Hou, Z.H. Enhancement of built-in electric field strength of BiOCl/NMT Z-scheme heterojunctions through photoinitiated defects for optimized photocatalytic performance. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 17179–17188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenstecher, P.; Conti, G.; Faigón, A.; Piñeiro, G. Tracing service crops’ net carbon and nitrogen rhizodeposition into soil organic matter fractions using dual isotopic brush-labeling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 184, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabella, J.P.; von Haden, A.; Sanford, G.; Ruark, M.; Zhu-Barker, X. Fate of synthetic fertilizer nitrogen in a maize system depends on dairy manure type: Insights from an isotopic tracing field study. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2025, 61, 1405–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.A.; Nippert, J.B.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Messina, C.D.; Ciampitti, I.A. Post-silking 15N labelling reveals an enhanced nitrogen allocation to leaves in modern maize (Zea mays) genotypes. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 268, 153577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yan, L.; Riaz, M.; White, P.J.; Yi, C.; Wang, S.L.; Shi, L.; Xu, F.S.; Wang, C.; Cai, H.M.; et al. Integrated transcriptome and metabolome analysis reveals the physiological and molecular responses of allotetraploid rapeseed to ammonium toxicity. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 189, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q.N.; Sha, Z.M.; Nakamura, T.; Oka, N.; Osaki, M.; Watanabe, T. Differential responses of soybean and sorghum growth, nitrogen uptake, and microbial metabolism in the rhizosphere to cattle manure application: A rhizobox study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 8084–8094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.C.; Ahmed, W.; Jiang, T.; Yang, D.H.; Yang, L.Y.; Hu, X.D.; Zhao, M.W.; Peng, X.C.; Yang, Y.F.; Zhang, W.; et al. Amino acid metabolism pathways as key regulators of nitrogen distribution in tobacco: Insights from transcriptome and WGCNA analyses. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, B.L.; Monk, N.A.M.; Clayton, R.H.; Osborne, C.P. Implementing a framework of carbon and nitrogen feedback responses into a plant resource allocation model. In Silico Plants 2025, 7, diaf004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifikalhor, M.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Hassani, B.; Niknam, V.; Lastochkina, O. Diverse role of γ-aminobutyric acid in dynamic plant cell responses. Plant Cell Rep. 2019, 38, 847–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, K.I.; Naeem, M.; Aftab, T. From neurotransmitter to plant protector: The intricate world of GABA signaling and its diverse functions in stress mitigation. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 403–418. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, T.F.S.; Ferreira, T.C.; Bomfim, N.C.P.; Aguilar, J.V.; de Camargos, L.S. Metabolic Responses to Excess Manganese in Legumes: Variations in Nitrogen Compounds in Canavalia ensiformis (L.) DC and Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp. Legume Sci. 2024, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarditi, A.M.; Klipfel, M.W.; Rodriguez, A.M.; Suvire, F.D.; Chasse, G.A.; Farkas, O.; Perczel, A.; Enriz, R.D. An ab initio exploratory study of side chain conformations for selected backbone conformations of N-acetyl-L-glutamine-N-methylamide. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 2001, 545, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, K.; Abreu, I.N.; Feussner, K.; Zienkiewicz, K.; Herrfurth, C.; Ischebeck, T.; Janz, D.; Majcherczyk, A.; Schmitt, K.; Valerius, O.; et al. Multi-omics analysis of xylem sap uncovers dynamic modulation of poplar defenses by ammonium and nitrate. Plant J. 2022, 111, 282–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.Q.; Yu, M.Q.; Zhu, X.B.; Nai, F.; Yang, R.R.; Wang, L.L.; Liu, Y.P.; Wei, Y.H.; Ma, X.M.; Yu, H.D.; et al. TaGSr contributes to low-nitrogen tolerance by optimizing nitrogen uptake and assimilation in Arabidopsis. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2024, 219, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.H.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, W.; Wei, M.; Zhao, L.; Li, G.B. Different nitrogen concentrations affect strawberry seedlings nitrogen form preferences through nitrogen assimilation and metabolic pathways. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 332, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.F.; Wang, Y.Q.; Cai, C.X.; Li, L.N.; Zeng, Y.; Cheng, X.; Shen, W.B. Molecular hydrogen positively regulates nitrate uptake and seed size by targeting nitrate reductase. Plant Physiol. 2023, 193, 2734–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffel, S.; Del Rosario, J.; Lacombe, B.; Rouached, H.; Gutiérrez, R.A.; Coruzzi, G.M.; Krouk, G. Nitrate sensing and signaling in plants: Comparative insights and nutritional interactions. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2025, 76, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.J.; Sun, Z.R.; Liu, W.L.; Chen, L.; Du, Y.; Wei, X.X. Correlation analysis between the rate of respiration in the root and the active components in licorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis). Exp. Ther. Med. 2014, 7, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, Q.; Fang, C.; Yuan, X.Y.; Agathokleous, E.; He, H.X.; Zheng, H.; Feng, Z.Z. Nitrogen addition changed the relationships of fine root respiration and biomass with key physiological traits in ozone-stressed poplars. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 875, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Mas, I.; Marino, D.; de la Peña, M.; Fuertes-Mendizábal, T.; González-Murua, C.; Estavillo, J.M.; González-Moro, M.B. Enhanced photorespiratory and TCA pathways by elevated CO2 to manage ammonium nutrition in tomato leaves. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 217, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.W.; Guo, X.L.; Zhu, X.L.; Gu, P.Y.; Zhang, W.; Tao, W.Q.; Wang, D.J.; Wu, Y.Z.; Zhao, Q.Z.; Xu, G.H.; et al. Strigolactone and gibberellin signaling coordinately regulate metabolic adaptations to changes in nitrogen availability in rice. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Li, Q.; An, Y.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.; He, F.; Chen, L.Y.; Liu, C.; Mao, W.; Wang, X.F.; et al. The transcription factor GNC optimizes nitrogen use efficiency and growth by up-regulating the expression of nitrate uptake and assimilation genes in poplar. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 4778–4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.H.; Nan, L.L.; Wang, K.; Xia, J.; Ma, B.; Cheng, J. Integrative leaf anatomy structure, physiology, and metabolome analyses revealed the response to drought stress in sainfoin at the seedling stage. Phytochem. Anal. 2024, 35, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z. Integration of Non-Invasive Micro-Test Technology and 15N Tracing Reveals the Impact of Nitrogen Forms at Different Concentrations on Respiratory and Primary Metabolism in Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010317

Chen Y, Cao Y, Jiang Y, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Sun Z. Integration of Non-Invasive Micro-Test Technology and 15N Tracing Reveals the Impact of Nitrogen Forms at Different Concentrations on Respiratory and Primary Metabolism in Glycyrrhiza uralensis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):317. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010317

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Ying, Yisu Cao, Yuan Jiang, Yanjun Wang, Zhengru Zhang, Yuanfan Zhang, and Zhirong Sun. 2026. "Integration of Non-Invasive Micro-Test Technology and 15N Tracing Reveals the Impact of Nitrogen Forms at Different Concentrations on Respiratory and Primary Metabolism in Glycyrrhiza uralensis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010317

APA StyleChen, Y., Cao, Y., Jiang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Y., & Sun, Z. (2026). Integration of Non-Invasive Micro-Test Technology and 15N Tracing Reveals the Impact of Nitrogen Forms at Different Concentrations on Respiratory and Primary Metabolism in Glycyrrhiza uralensis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010317