GhmiR156-GhSPL2 Module Regulates Anthocyanin Biosynthesis of Ray Florets in Gerbera hybrida

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

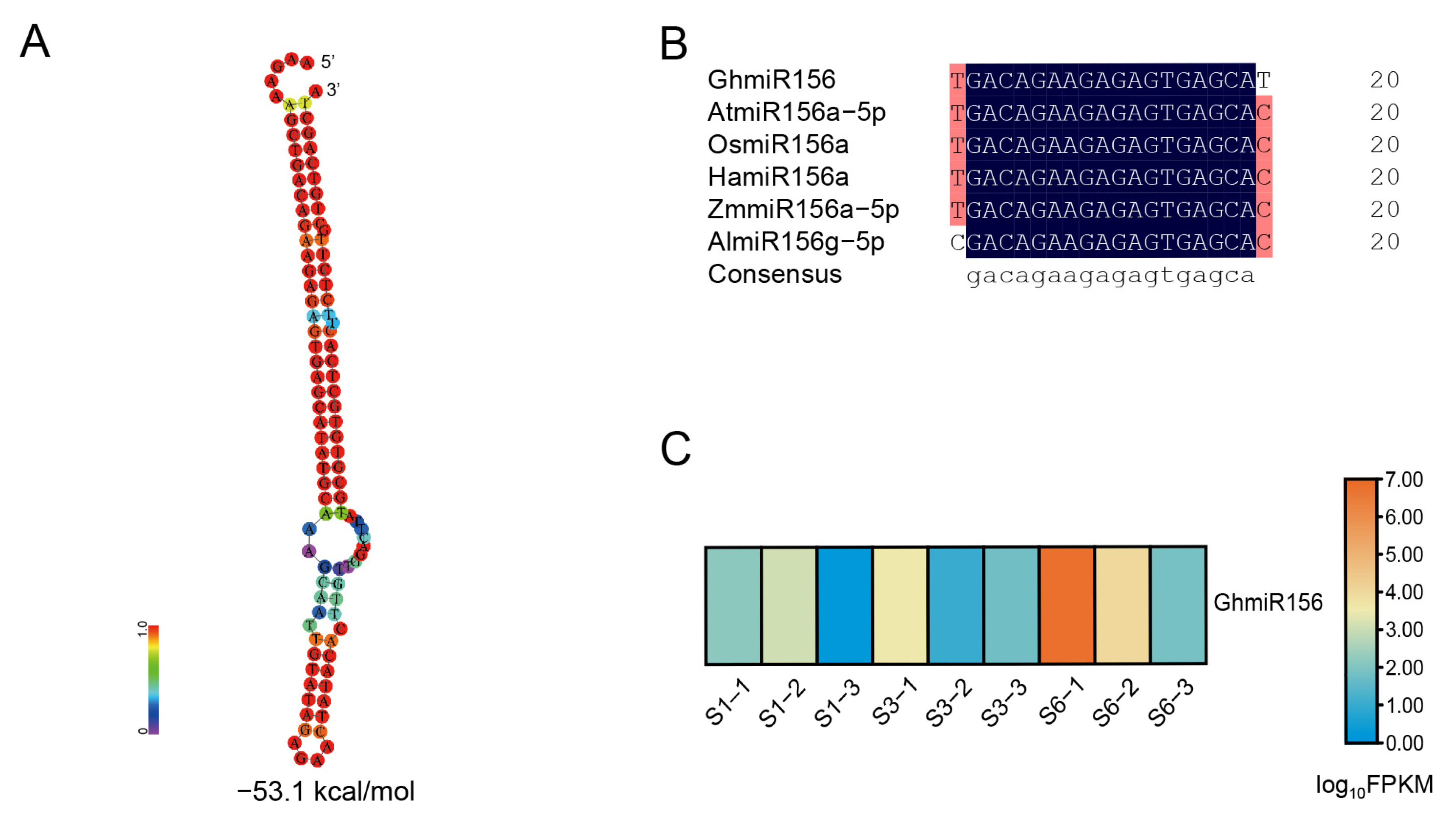

2.1. Identification and Characterization of miR156 in Gerbera

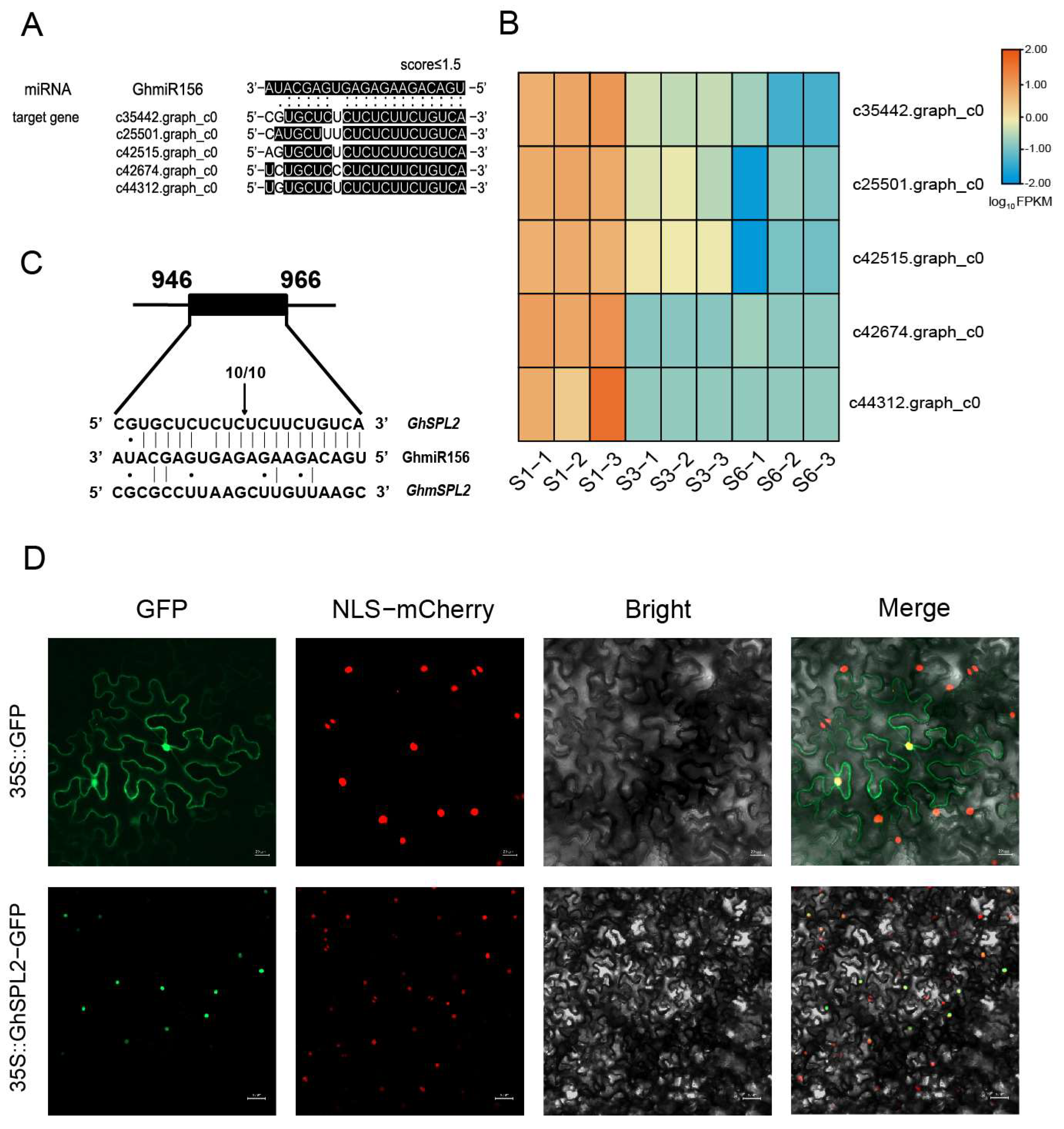

2.2. Identification of GhmiR156 Targets and Functional Characterization of GhSPL2

2.3. GhSPL2 Is a Direct Target of GhmiR156

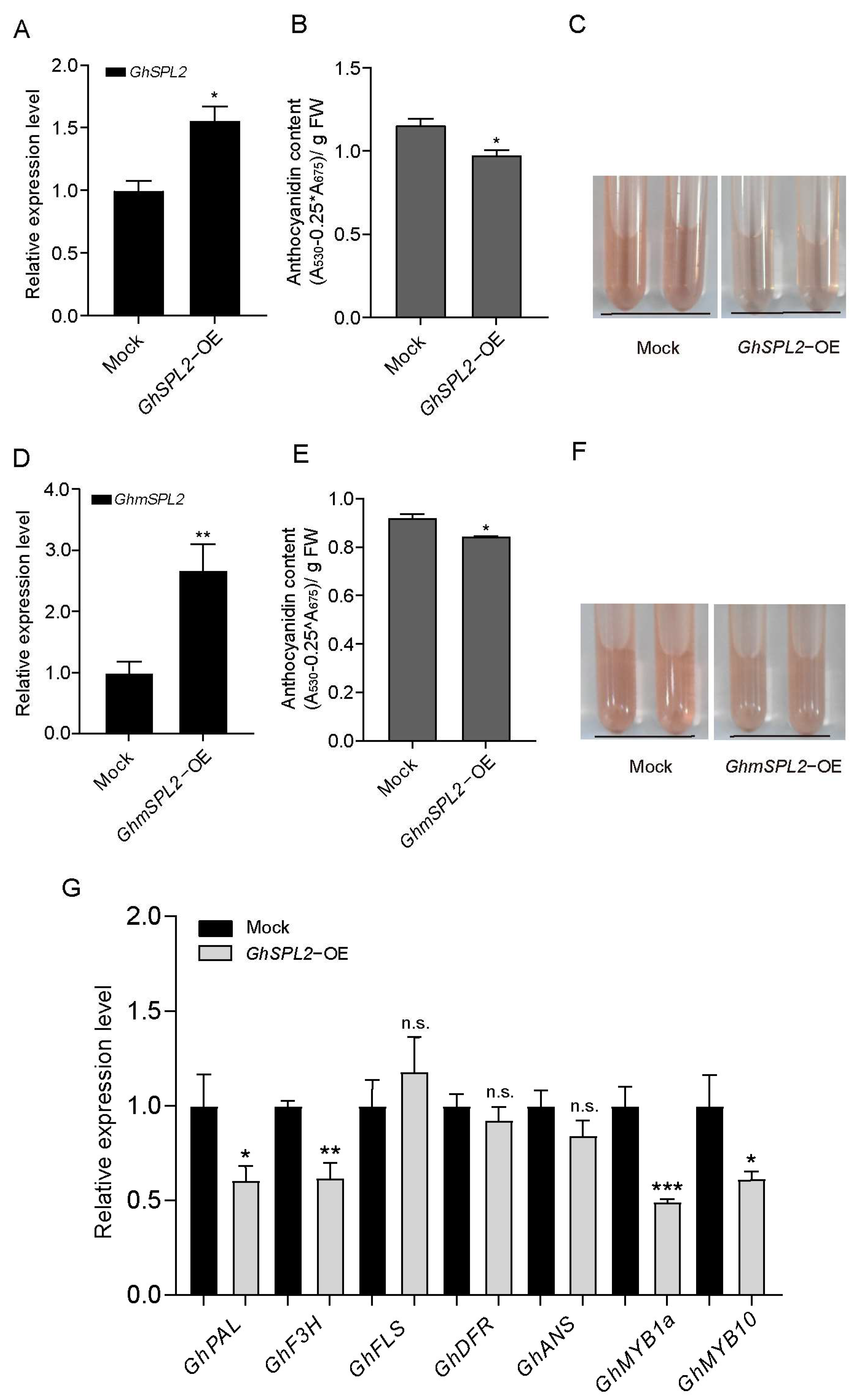

2.4. Overexpression of GhSPL2 Inhibits Anthocyanin Accumulation in Ray Florets

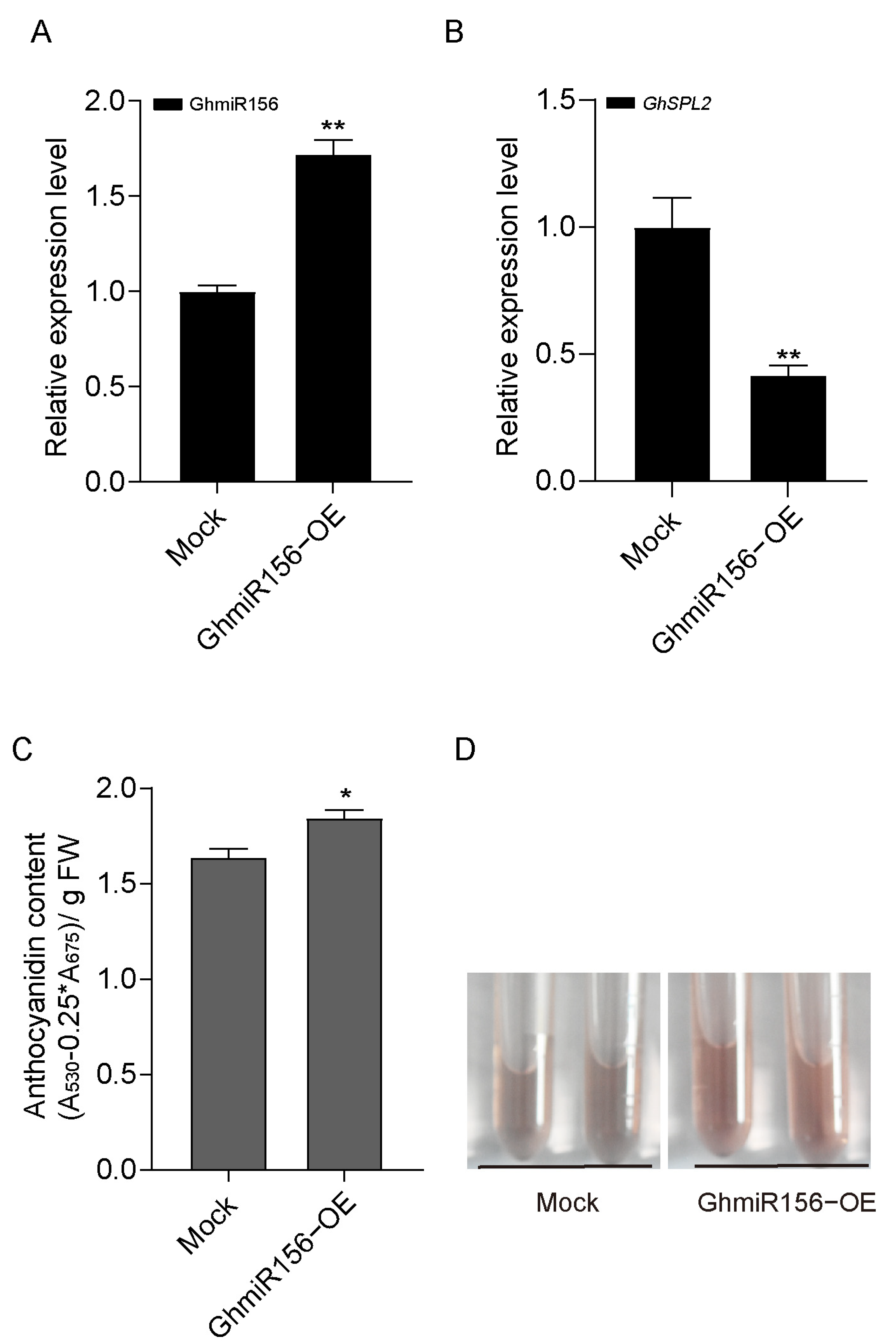

2.5. GhmiR156 Relieves Negative Regulation by GhSPL2 in Ray Floret Anthocyanin Accumulation

3. Discussion

3.1. GhSPL2 Inhibits Anthocyanin Synthesis by Influencing the Expression of Anthocyanin-Related Genes

3.2. GhmiR156 Targeting GhSPL2 Regulates Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Gerbera

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

4.2. Bioinformatic Analysis

4.3. Cloning and Bioinformatics Analysis of GhSPL2

4.4. RNA Extraction and Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

4.5. Subcellular Localization of GhSPL2

4.6. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

4.7. Western Blotting Analysis

4.8. RNA Ligase-Mediated 5′ RACE(RLM-5′RACE)

4.9. Transient Transformation of Ray Florets

4.10. Measurement of Total Anthocyanin Content

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fan, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, H.; Tian, W.; Xue, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, H.; Wu, Y. Flower morphology, flower color, flowering and floral fragrance in Paeonia L. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1467596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LópezMartínez, A.; Magallón, S.; vonBalthazar, M.; Schönenberger, J.; Sauquet, H.; Chartier, M. Angiosperm flowers reached their highest morphological diversity early in their evolutionary history. New Phytol. 2023, 241, 1348–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RomeroBravo, A.; Castellanos, M. Nectar and floral morphology differ in evolutionary potential in novel pollination environments. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Y.; Ashraf, U.; Wang, D.; Hassan, W.; Zou, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Abbas, F. Function of anthocyanin and chlorophyll metabolic pathways in the floral sepals color formation in different hydrangea cultivars. Plants 2025, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Yu, C.; Han, Y.; Guo, X.; Luo, L.; Pan, H.; Zheng, T.; Wang, J.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Q. Determination of flavonoids and carotenoids and their contributions to various colors of rose cultivars (Rosa spp.). Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zeng, Z.; Song, C.; Lv, Q.; Chen, G.; Mo, G.; Gong, L.; Jin, S.; Huang, R.; Huang, B. Color-induced changes in Chrysanthemum morifolium: An integrative transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis of petals and non-petals. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1498577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Tao, J. Recent advances on the development and regulation of flower color in ornamental plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Tian, Y.; Guo, P.; Luo, J.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Xie, Q.; Hu, Z. Novel insights into pigment composition and molecular mechanisms governing flower coloration in rose cultivars exhibiting diverse petal hues. Plants 2024, 13, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, L.; Qiang, X.; Meng, Y.; Li, Z.; Huang, F. Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic profiles provide insights into the mechanisms of anthocyanin and carotenoid biosynthesis in petals of Medicago sativa ssp. sativa and Medicago sativa ssp. falcata. Plants 2024, 13, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Miki, N.; Momonoi, K.; Kawachi, M.; Katou, K.; Okazaki, Y.; Uozumi, N.; Maeshima, M.; Kondo, T. Synchrony between flower opening and petal-color change from red to blue in morning glory, Ipomoea tricolor cv. Heavenly Blue. Proc. Jpn. Acad. 2009, 85, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheynier, V.; Comte, G.; Davies, K.M.; Lattanzio, V.; Martens, S. Plant phenolics: Recent advances on their biosynthesis, genetics, and ecophysiology. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 72, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Sasaki, N.; Ohmiya, A. Biosynthesis of plant pigments: Anthocyanins, betalains and carotenoids. Plant J. 2008, 54, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Yang, R.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Hu, Z.; Guo, S.; Zhang, H.; et al. MiR156 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis through SPL targets and other microRNAs in poplar. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, Y.; Xie, X.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, C.; Bian, S.; Hancock, R. A blueberry MIR156a–SPL12 module coordinates the accumulation of chlorophylls and anthocyanins during fruit ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 5976–5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Ni, J.; Niu, Q.; Bai, S.; Bao, L.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D.; Teng, Y. Response of miR156-SPL module during the red peel coloration of bagging-treated Chinese sand pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai). Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirumalai, V.; Swetha, C.; Nair, A.; Pandit, A.; Shivaprasad, P.V. miR828 and miR858 regulate VvMYB114 to promote anthocyanin and flavonol accumulation in grapes. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 4775–4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, J.; Felippes, F.F.; Liu, C.; Weigel, D.; Wang, J. Negative regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis by a miR156-targeted SPL transcription factor. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Cai, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z. Overexpression of microRNA828 reduces anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. Cult. 2013, 115, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Tian, J.; Luo, R.; Kang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Liu, N.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, H.; Niu, S.; et al. MiR399d and epigenetic modification comodulate anthocyanin accumulation in Malus leaves suffering from phosphorus deficiency. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhao, P.; Chen, G.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. A comparative analysis of small RNA sequencing data in tubers of purple potato and its red mutant reveals small RNA regulation in anthocyanin biosynthesis. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodder, J. miRNA-mediated regulation of auxin signaling pathway during plant development and stress responses. J. Biosci. 2020, 45, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GaeteLoyola, J.; Olivares, F.; Saavedra, G.; Zúñiga, T.; Mora, R.; Ríos, I.; Valdovinos, G.; Barrera, M.; Almeida, A.; Prieto, H. Artificial sweet cherry miRNA 396 promotes early flowering in vernalization-dependent Arabidopsis edi-0 Ecotype. Plants 2025, 14, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattolin, S.; Cirilli, M.; Pacheco, I.; Ciacciulli, A.; Da Silva Linge, C.; Mauroux, J.B.; Lambert, P.; Cammarata, E.; Bassi, D.; Pascal, T.; et al. Deletion of the miR172 target site in a TOE-type gene is a strong candidate variant for dominant double-flower trait in Rosaceae. Plant J. 2018, 96, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Shen, P.; Yang, M.; Meng, Q.; Zhou, R.; Li, L.; Lin, S. Integrated analysis of microRNAs and transcription factor targets in floral transition of Pleioblastus pygmaeus. Plants 2024, 13, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.-J.; Shang, G.-D.; Xu, Z.-G.; Yu, S.; Wu, L.-Y.; Zhai, D.; Tian, S.-L.; Gao, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.-W. Cell division in the shoot apical meristem is a trigger for miR156 decline and vegetative phase transition in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2115667118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Shu, Q.; Lin, W.; Allan, A.; Espley, R.; Su, J.; Pei, M.; Wu, J. The PyPIF5-PymiR156a-PySPL9-PyMYB114/MYB10 module regulates light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in red pear. Mol. Hortic. 2021, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Q.; Fan, L.; Liu, T.; Qiu, Y.; Du, J.; Mo, B.; Chen, M.; Chen, X. MicroRNA156 conditions auxin sensitivity to enable growth plasticity in response to environmental changes in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhang, X.; Du, B.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, T. MicroRNA156ab regulates apple plant growth and drought tolerance by targeting transcription factor MsSPL13. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 1836–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Li, F.; Ma, Q.; Shen, T.; Jiang, J.; Li, H. The miR156-SPL4/SPL9 module regulates leaf and lateral branch development in Betula platyphylla. Plant Sci. 2024, 338, 111869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, S.; Zhai, L.; Cui, Y.; Tang, G.; Huo, J.; Li, X.; Bian, S. The miR156/SPL12 module orchestrates fruit colour change through directly regulating ethylene production pathway in blueberry. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 22, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yao, J.; Hua, K.; Liu, X.; Shi, H.; Zhu, J. The grain yield modulator miR156 regulates seed dormancy through the gibberellin pathway in rice. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H. The miR156/SPL module, a regulatory hub and versatile toolbox, gears up crops for enhanced agronomic traits. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Niu, Q.; Ng, K.; Chua, N. The role of miR156/SPLs modules in Arabidopsis lateral root development. Plant J. 2015, 83, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Gao, Z.; Sun, S.; Zhang, L.; Irfan, M.; Chen, L. Insights into microRNA regulation of flower coloration in a lily cultivar Vivian petal. Ornam. Plant Res. 2023, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tan, C.; Zhang, Z.; Xue, L.; Lei, J. Comparative transcriptome analysis uncovers the regulatory roles of microRNAs involved in petal color change of pink-flowered strawberry. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 854508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Luo, S.; Fu, Y.; Kong, C.; Wang, K.; Sun, D.; Li, M.; Yan, Z.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, Y. Genome-wide identification and comparative profiling of microRNAs reveal flavonoid biosynthesis in two contrasting flower color cultivars of tree peony. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 797799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Xia, X.; Wei, M.; Sun, J.; Meng, J.; Tao, J. Overexpression of herbaceous peony miR156e-3p improves anthocyanin accumulation in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana lateral branches. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Wang, X. Regulation of fower development and anthocyanin accumulation in Gerbera hybrida. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2004, 79, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elomaa, P.; Uimari, A.; Mehto, M.; Albert, V.A.; Laitinen, R.A.E.; Teeri, T.H. Activation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Gerbera hybrida (Asteraceae) suggests conserved protein-protein and protein-promoter interactions between the anciently diverged monocots and eudicots. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 1831–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, R.; Ainasoja, M.; Broholm, S.; Teeri, T.; Elomaa, P. Identification of target genes for a MYB-type anthocyanin regulator in Gerbera hybrida. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 3691–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Tang, Y.; Pang, B.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Deng, J.; Feng, C.; Li, L.; Ren, G.; Wang, Y.; et al. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor GhMYB1a regulates flavonol and anthocyanin accumulation in Gerbera hybrida. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Huang, S.; Huang, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. 14-3-3 proteins are involved in BR-induced ray petal elongation in Gerbera hybrida. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 718091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, N.; Lin, X.; Situ, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. Pectin methylesterase inhibitor 58 negatively regulates ray petal elongation by inhibiting cell expansion in Gerbera hybrida. Plant Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Jin, X.; Yao, W.; Kong, L.J.; Huang, G.; Tao, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, X.J.; Wang, Y.Q. A Mini Zinc-Finger Protein (MIF) from activates the GASA protein family gene, GEG, to inhibit ray petal elongation. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Yuan, W.; Yao, W.; Jin, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. A regulatory GhBPE-GhPRGL module maintains ray petal length in Gerbera hybrida. Mol. Hortic. 2022, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Liao, B.; Lin, X.; Luo, Q.; Huang, X.; Wang, X.; Shan, Q.; Wang, Y. Integrative analysis of miRNAs and their targets involved in ray floret growth in Gerbera hybrida. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Ma, M.; Wang, B.; Shen, R.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, H. FHY3 and FAR1 integrate light signals with the miR156-SPL module-mediated aging pathway to regulate Arabidopsis flowering. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhou, B.; Wu, X.; Wu, H.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, M.; Guo, B.; et al. Molecular characterization of SPL gene family during flower morphogenesis and regulation in blueberry. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ni, X.; Fu, X.; Taheri, A.; Zhang, W.; Liu, P.; Liu, H.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Tang, K. Comprehensive analysis of SPL gene family and miR156a/SPLs in the regulation of terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus L. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Wang, X.; Xuan, X.; Sheng, Z.; Jia, H.; Emal, N.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, T.; Wang, C.; Fang, J. Characterization and action mechanism analysis of VvmiR156b/c/d-VvSPL9 module responding to multiple-hormone signals in the modulation of grape berry color formation. Foods 2021, 10, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Lai, B.; Hu, B.; Qin, Y.; Hu, G.; Zhao, J. Identification of microRNAs and their target genes related to the accumulation of anthocyanins in Litchi chinensis by high-throughput sequencing and degradome analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, L.; Cao, S.; Chen, W.; Yang, Z. Involvement of a MYB transcription factor in anthocyanin biosynthesis during chinese bayberry (Morella rubra) fruit ripening. Biology 2023, 12, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, S.; Wang, H.; Ming, F. The MYB transcription factor RcMYB1 plays a central role in rose anthocyanin biosynthesis. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyissa, B.A.; Arshad, M.; Gruber, M.; Kohalmi, S.; Hannoufa, A. The interplay between miR156/SPL13 and DFR/WD40–1 regulate drought tolerance in alfalfa. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Tomes, S.; Gleave, A.; Zhang, H.; Dare, A.; Plunkett, B.; Espley, R.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, R.; Allan, A.; et al. microRNA172 targets APETALA2 to regulate flavonoid biosynthesis in apple (Malus domestica). Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhab007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, S.; Mei, Z.; Yu, L.; Wang, C.; Mao, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chen, X.; et al. Mdm-miR858 targets MdMYB9 and MdMYBPA1 to participate anthocyanin biosynthesis in red-fleshed apple. Plant J. 2023, 113, 1295–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Shan, J.; Shi, M.; Gao, J.; Lin, H. The miR156-SPL9-DFR pathway coordinates the relationship between development and abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant J. 2014, 80, 1108–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, K.; Lin, Y.; Ren, J.; Bai, L.; Miao, Y.; An, G.; Song, C. Modulation of the phosphate-deficient responses by microRNA156 and its targeted SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE 3 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qi, F.; Sun, D.; Cui, Y.; Huang, H. Integrated transcriptome and small RNA sequencing revealing miRNA-mediated regulatory network of bicolour pattern formation in Pericallis hybrida ray florets. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 326, 112765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Ran, L.; Zhou, R.; Wang, Z. The transcriptome of Dahlia pinnata provides comprehensive insight into the formation mechanism of polychromatic petals. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuela, D.; Du, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liao, Y.; Hu, T.; Fouracre, J.P.; Xu, M. Redundant functions of miR156-targeted SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE transcription factors in promoting cauline leaf identity. New Phytol. 2025, 247, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ye, Y.; Xu, M.; Feng, L.; Xu, L. Roles of the SPL gene family and miR156 in the salt stress responses of tamarisk (Tamarix chinensis). BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Salinas, M.; Garcia-Molina, A.; Höhmann, S.; Berndtgen, R.; Huijser, P. SPL8 and miR156-targeted SPL genes redundantly regulate Arabidopsis gynoecium differential patterning. Plant J. 2013, 75, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, H.; Ma, N.; Tian, J.; Luo, J.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, X.; Fei, Z.; Gao, J. An NAC transcription factor controls ethylene-regulated cell expansion in flower petals. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; vanBaren, M.; Salzberg, S.; Wold, B.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Estrella, L.; Kuang, Q.; Li, L.; Peng, J.; Sun, S.; Wang, X. Transcriptome analysis of Gerbera hybrida ray florets: Putative genes associated with gibberellin metabolism and signal transduction. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57715. [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.; Schmittgen, T. Analysis of relative gene expression data using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellens, R.; Allan, A.; Friel, E.; Bolitho, K.; Grafton, K.; Templeton, M.; Karunairetnam, S.; Gleave, A.; Laing, W. Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods 2005, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Wang, C.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. ThHSFA1 confers salt stress tolerance through modulation of reactive oxygen species scavenging by directly regulating ThWRKY4. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, P.; Zhao, Q.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Jiang, H.; Wu, G. Overexpression of a phosphate starvation response AP2/ERF gene from physic nut in Arabidopsis alters root morphological traits and phosphate starvation-induced anthocyanin accumulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Liao, B.; Shi, S.; Luo, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. GhmiR156-GhSPL2 Module Regulates Anthocyanin Biosynthesis of Ray Florets in Gerbera hybrida. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010318

Li M, Liao B, Shi S, Luo Q, Chen Y, Wang X, Wang Y. GhmiR156-GhSPL2 Module Regulates Anthocyanin Biosynthesis of Ray Florets in Gerbera hybrida. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010318

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Mengdi, Bingbing Liao, Shuyuan Shi, Qishan Luo, Yanbo Chen, Xiaojing Wang, and Yaqin Wang. 2026. "GhmiR156-GhSPL2 Module Regulates Anthocyanin Biosynthesis of Ray Florets in Gerbera hybrida" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010318

APA StyleLi, M., Liao, B., Shi, S., Luo, Q., Chen, Y., Wang, X., & Wang, Y. (2026). GhmiR156-GhSPL2 Module Regulates Anthocyanin Biosynthesis of Ray Florets in Gerbera hybrida. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010318