A Combined Bioinformatics and Clinical Validation Study Identifies MDM2, FKBP5 and CTNNA1 as Diagnostic Gene Signatures for COPD in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification of COPD-Associated Gene Co-Expression Modules

2.2. Functional Enrichment Analysis of Key Modules

2.3. Selection of Candidate Genes for Clinical Validation

2.4. Clinical Cohort Characterization

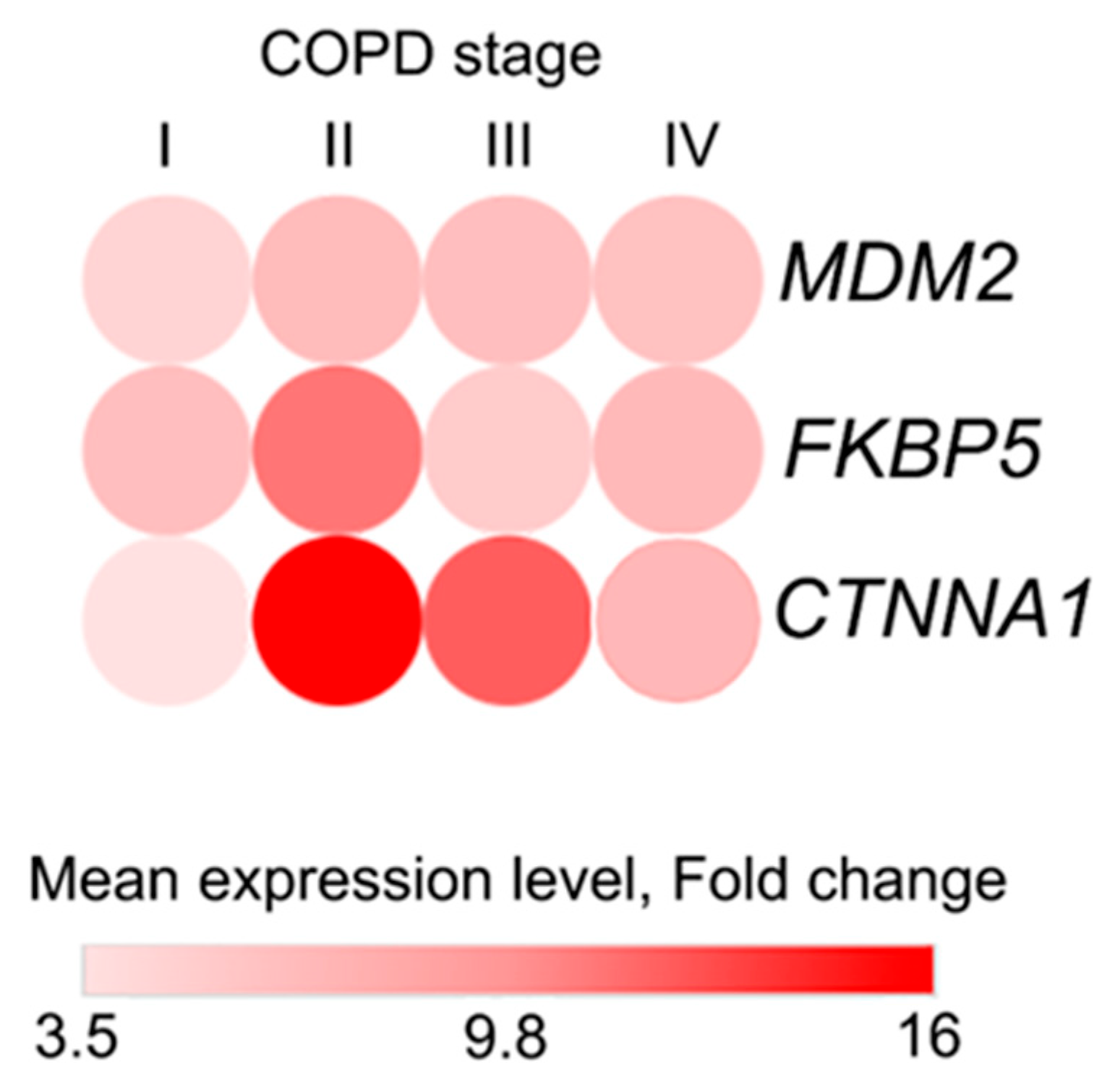

2.5. Validation of Candidate Gene Expression in a Clinical Cohort

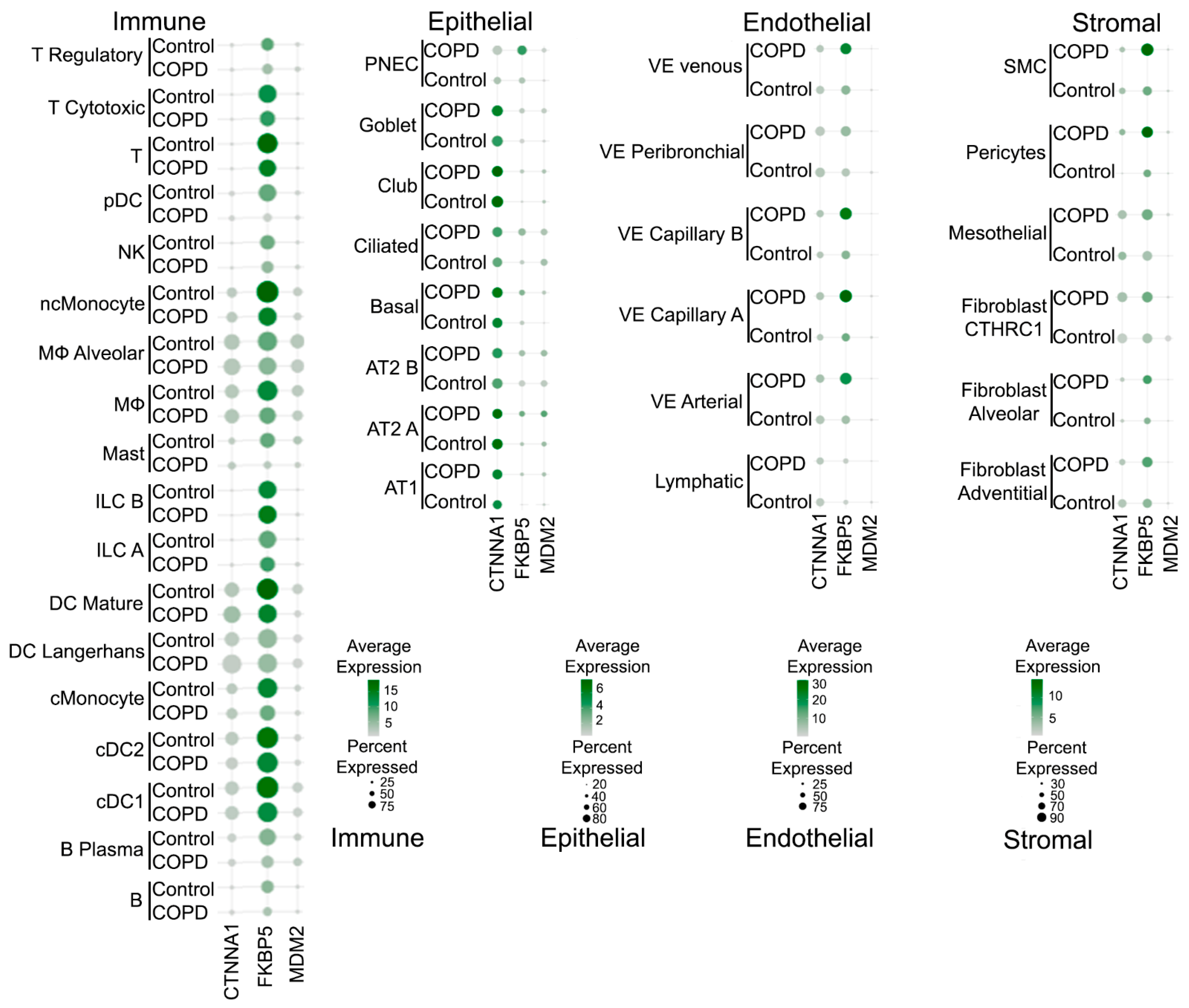

2.6. Network and Text-Mining Analysis of Validated Biomarkers

3. Discussion

Limitations of This Study

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Dataset Selection and Preprocessing

4.2. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

4.3. Functional Enrichment and Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Analysis

4.4. Patient Cohort and Ethical Approval

4.5. PBMC Isolation and RNA Extraction

4.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR)

4.7. ROC Analysis

4.8. Data Mining Analysis

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.; Lin, J.; Liang, L.; Huang, F.; Yao, X.; Peng, K.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, J. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Its Attributable Risk Factors from 1990 to 2021: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Respir. Res. 2025, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakakos, A.; Sotiropoulou, Z.; Anagnostopoulos, N.; Vontetsianos, A.; Cholidou, K.; Papaioannou, A.I.; Bartziokas, K. Anti-Inflammatory Agents for the Management of COPD-Quo Vadis? Respir. Med. 2025, 248, 108396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Khathlan, N.; Badghish, L.O.; Alrehaili, H.H.; Al Luhaybi, K.H.O.; Alnakhli, M.A.; Alotaibi, A.J. A Bibliometric Analysis of Pulmonary Function Testing in Differentiating Asthma From COPD: Trends, Impact, and Emerging Research Areas. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2025, 18, 6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matera, M.G.; Page, C.P.; Calzetta, L.; Rogliani, P.; Cazzola, M. Pharmacology and Therapeutics of Bronchodilators Revisited. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 72, 218–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, S.; Fan, X.; He, J.; Li, Q.; Jin, H. New Approaches to Treating Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease with Colla Corii Asini. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Li, T.; Zhou, L.; Song, Y.; Hu, L. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Antibiotic Intervention of Lower Airway Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Colonization in Patients with Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. COPD J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2025, 22, 2564743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, B.; Fabbri, L.; Criner, G.; Martinez, F.J.; Mannino, D.; Vogelmeier, C.; de Oca, M.M.; Papi, A.; Sin, D.D.; Han, M.L.K.; et al. Definition and Nomenclature of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Time for Its Revision. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çolak, Y.; Afzal, S.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Vestbo, J.; Lange, P. Prevalence, Characteristics, and Prognosis of Early Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. The Copenhagen General Population Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, C.; Wang, K.; Yang, K.; Zhong, Y.; Gul, A.; Luo, W.; Yalikun, M.; He, J.; Chen, W.; Xu, W.; et al. Toward Precision Medicine in COPD: Phenotypes, Endotypes, Biomarkers, and Treatable Traits. Respir. Res. 2025, 26, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, L.; Xu, C.; Zhang, J. Biomarkers in COPD-Associated PH/CCP: Circulating Molecules and Cell-Intrinsic Marker. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2025, 20, 2869–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazopoulos, I.; Magounaki, K.; Kotsiou, O.; Rouka, E.; Perlikos, F.; Kakavas, S.; Gourgoulianis, K. Incorporating Biomarkers in COPD Management: The Research Keeps Going. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvanny, A.; Pattwell, C.; Beech, A.; Southworth, T.; Singh, D. Validation of Sputum Biomarker Immunoassays and Cytokine Expression Profiles in COPD. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniscalco, M.; Candia, C.; Ambrosino, P.; Iovine, A.; Fuschillo, S. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease’s Eosinophilic Phenotype: Clinical Characteristics, Biomarkers and Biotherapy. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 131, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Gao, L.; Ma, H.X.; Wei, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.H.; Qin, K.R.; Wang, W.T.; Wang, H.L.; Pang, M. Clinical Value of IL-13 and ECP in the Serum and Sputum of Eosinophilic AECOPD Patients. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 1290–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, M.; Silverman, E.K. Precision Approaches to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Management. Annu. Rev. Med. 2024, 75, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukowry, P.S.; Spittle, D.A.; Turner, A.M. Small Airways Disease, Biomarkers and Copd: Where Are We? Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2021, 16, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilescu, D.M.; Martinez, F.J.; Marchetti, N.; Galbán, C.J.; Hatt, C.; Meldrum, C.A.; Dass, C.; Tanabe, N.; Reddy, R.M.; Lagstein, A.; et al. Noninvasive Imaging Biomarker Identifies Small Airway Damage in Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.L.; Liu, S.F. Exploring Molecular Mechanisms and Biomarkers in COPD: An Overview of Current Advancements and Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Niu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; He, Y.; Liu, X. Identification of Novel Biomarkers Related to Neutrophilic Inflammation in COPD. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1410158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, E.K. Genetics of COPD. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2020, 82, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Chang, Y.P.; Huang, K.T.; Hsu, P.Y.; Hsiao, C.C.; Lin, M.C. Unraveling the Pathogenesis of Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Overlap: Focusing on Epigenetic Mechanisms. Cells 2022, 11, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Cordero, A.I.; Yang, C.X.; Milne, S.; Li, X.; Hollander, Z.; Chen, V.; Ng, R.; Tebbutt, S.J.; Leung, J.M.; Sin, D.D. Epigenetic Blood Biomarkers of Ageing and Mortality in COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58, 2101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.L.; Chiang, T.I.; Chen, C.L. Identification and Validation of SPP1 as a Potential Biomarker for COPD through Comprehensive Bioinformatics Analysis. Respir. Med. 2025, 237, 107953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Zhong, Z.; Wu, B.; Yang, Y.; Kong, L.; Xia, S.; Xiao, G. Identifying Pyroptosis-Related Prognostic Genes in the Co-Occurrence of Lung Adenocarcinoma and COPD via Bioinformatics Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellingsen, J.; Janson, C.; Bröms, K.; Hårdstedt, M.; Högman, M.; Lisspers, K.; Palm, A.; Ställberg, B.; Malinovschi, A. CRP, Fibrinogen, White Blood Cells, and Blood Cell Indices as Prognostic Biomarkers of Future COPD Exacerbation Frequency: The TIE Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riou, M.; Alfatni, A.; Charles, A.L.; Andres, E.; Pistea, C.; Charloux, A.; Geny, B. New Insights into the Implication of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Tissue, Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells, and Platelets during Lung Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragonieri, S.; Bikov, A.; Capuano, A.; Scarlata, S.; Carpagnano, G.E. Methodological Aspects of Induced Sputum. Adv. Respir. 2023, 91, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg, J.C.; Timens, W. The Pathology of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2009, 4, 435–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agustí, A.; Melén, E.; DeMeo, D.L.; Breyer-Kohansal, R.; Faner, R. Pathogenesis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Understanding the Contributions of Gene–environment Interactions across the Lifespan. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.; Qin, J.; Srivenugopal, K.S.; Wang, M.; Zhang, R. The MDM2-P53 Pathway Revisited. J. Biomed. Res. 2013, 27, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Zhang, X.; Xing, W.; Wang, Q.; Liang, G.; He, Z. Cigarette Smoke Extract Mediates Cell Premature Senescence in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients by Up-Regulating USP7 to Activate P300-P53/P21 Pathway. Toxicol. Lett. 2022, 359, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancox, R.J.; Poulton, R.; Welch, D.; McLachlan, C.R.; Olova, N.; Robertson, S.P.; Greene, J.M.; Sears, M.R.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; et al. Accelerated Decline in Lung Function in Cigarette Smokers Is Associated with TP53/MDM2 Polymorphisms. Hum. Genet. 2009, 126, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, E.B. The Role of FKBP5, a Co-Chaperone of the Glucocorticoid Receptor in the Pathogenesis and Therapy of Affective and Anxiety Disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, S186–S195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejwani, V.; McCormack, A.; Suresh, K.; Woo, H.; Xu, N.; Davis, M.F.; Brigham, E.; Hansel, N.N.; McCormack, M.C.; D’Alessio, F.R. Dexamethasone-Induced FKBP51 Expression in CD4+ T-Lymphocytes Is Uniquely Associated With Worse Asthma Control in Obese Children with Asthma. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 744782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolongo, F.; Scarlata, S.; Tomino, C.; De Dominicis, C.; Giacconi, R.; Malavolta, M.; Bonassi, S.; Russo, P.; Prinzi, G. Psycho-Cognitive Assessment and Quality of Life in Older Adults with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease-Carrying the Rs4713916 Gene Polymorphism (G/A) of Gene FKBP5 and Response to Pulmonary Rehabilitation: A Proof of Concept Study. Psychiatr. Genet. 2022, 32, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, P.; Tomino, C.; Santoro, A.; Prinzi, G.; Proietti, S.; Kisialiou, A.; Cardaci, V.; Fini, M.; Magnani, M.; Collacchi, F.; et al. FKBP5 Rs4713916: A Potential Genetic Predictor of Interindividual Different Response to Inhaled Corticosteroids in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in a Real-Life Setting. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troyanovsky, R.B.; Indra, I.; Troyanovsky, S.M. Actin-Dependent α-Catenin Oligomerization Contributes to Adherens Junction Assembly. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalewski, D.P.; Ruszel, K.P.; Stępniewski, A.; Gałkowski, D.; Bogucki, J.; Kołodziej, P.; Szymańska, J.; Płachno, B.J.; Zubilewicz, T.; Feldo, M.; et al. Identification of Transcriptomic Differences between Lower Extremities Arterial Disease, Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm and Chronic Venous Disease in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Specimens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, P.; Negri, S.; Perna, A.; Rosti, V.; Guerra, G.; Moccia, F. Therapeutic Potential of Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells in Ischemic Disease: Strategies to Improve Their Regenerative Efficacy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, S.S. Epithelial and Endothelial Cell Plasticity in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Respir. Investig. 2017, 55, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, T.; Wang, L.F.; Yin, Y.Q. How Do Innate Immune Cells Contribute to Airway Remodeling in Copd Progression? Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2020, 15, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ShinyCell Human Lung CellRef-Default. Available online: https://app.lungmap.net/app/shinycell-human-lung-cellref (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Sauler, M.; McDonough, J.E.; Adams, T.S.; Kothapalli, N.; Barnthaler, T.; Werder, R.B.; Schupp, J.C.; Nouws, J.; Robertson, M.J.; Coarfa, C.; et al. Characterization of the COPD Alveolar Niche Using Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R Package for Weighted Correlation Network Analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. Fast R Functions for Robust Correlations and Hierarchical Clustering. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 46, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software; PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bindea, G.; Mlecnik, B.; Hackl, H.; Charoentong, P.; Tosolini, M.; Kirilovsky, A.; Fridman, W.H.; Pagès, F.; Trajanoski, Z.; Galon, J. ClueGO: A Cytoscape Plug-in to Decipher Functionally Grouped Gene Ontology and Pathway Annotation Networks. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1091–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-H.H.; Zhao, L.-F.F.; Wang, H.-F.F.; Wen, Y.-T.T.; Jiang, K.-K.K.; Mao, X.-M.M.; Zhou, Z.-Y.Y.; Yao, K.-T.T.; Geng, Q.-S.S.; Guo, D.; et al. GenCLiP 3: Mining Human Genes’ Functions and Regulatory Networks from Pubmed Based on Co-Occurrences and Natural Language Processing. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1973–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Type | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| MDM2 | Forward | 5′-AAGGAGAGCAATTAGTGAGACAG-3′ |

| Probe | 5′-((5,6)-FAM)-TTGTGGCGTTTTCTTTGTCGTTCACC-BHQ1-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-CCCTTATTACACACAGAGCCAG-3′ | |

| ALOX15B | Forward | 5′-TTCTCCAAGGGCTTCCTAAAC-3′ |

| Probe | 5′-((5,6)-FAM)-TGACATACTGCACCAGGGCTTCC-BHQ1-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-TCCAAGCACAGGAGTCAAAC-3′ | |

| NPM1 | Forward | 5′-AAGTATATCTGGAAAGCGGTCTG-3′ |

| Probe | 5′-((5,6)-FAM)-CCCTGGAGGTGGTAGCAAGGTTC-BHQ1-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-TTTTGGCTGGAGTATCTCGTATAG-3′ | |

| FKBP5 | Forward | 5′-CAGTCTCCCTAAAATTCCCTCG-3′ |

| Probe | 5′-((5,6)-FAM)-CCCTCTCCTTTCCGTTTGGTTCTCC-BHQ1-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-TTGCTCCTTCGTTTGGATTTG-3′ | |

| GSN | Forward | 5′-GCTGGATGACTACCTGAACG-3′ |

| Probe | 5′-((5,6)-FAM)-CCGACTCGAAGCCCTGGACC-BHQ1-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-TGAATCCTGATGCCACACC-3′ | |

| CTNNA1 | Forward | 5′-GAGATGACAGACTTTACCCGAG-3′ |

| Probe | 5′-((5,6)-FAM)-TCCTGGATCCTGCCTCAGCAATTT-BHQ1-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-GCAATGGTCTGCAATGGTG-3′ | |

| TBP | Forward | 5′-GATAAGAGAGCCACGAACCAC-3′ |

| Probe | 5′-((5,6)-ROX)-CACAGGAGCCAAGAGTGAAGAACAGT-BHQ2-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-CAAGAACTTAGCTGGAAAACCC-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Savin, I.A.; Sen’kova, A.V.; Markov, A.V.; Kotova, O.S.; Shpagin, I.S.; Shpagina, L.A.; Vlassov, V.V.; Zenkova, M.A. A Combined Bioinformatics and Clinical Validation Study Identifies MDM2, FKBP5 and CTNNA1 as Diagnostic Gene Signatures for COPD in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010273

Savin IA, Sen’kova AV, Markov AV, Kotova OS, Shpagin IS, Shpagina LA, Vlassov VV, Zenkova MA. A Combined Bioinformatics and Clinical Validation Study Identifies MDM2, FKBP5 and CTNNA1 as Diagnostic Gene Signatures for COPD in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010273

Chicago/Turabian StyleSavin, Innokenty A., Aleksandra V. Sen’kova, Andrey V. Markov, Olga S. Kotova, Ilya S. Shpagin, Lyubov A. Shpagina, Valentin V. Vlassov, and Marina A. Zenkova. 2026. "A Combined Bioinformatics and Clinical Validation Study Identifies MDM2, FKBP5 and CTNNA1 as Diagnostic Gene Signatures for COPD in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010273

APA StyleSavin, I. A., Sen’kova, A. V., Markov, A. V., Kotova, O. S., Shpagin, I. S., Shpagina, L. A., Vlassov, V. V., & Zenkova, M. A. (2026). A Combined Bioinformatics and Clinical Validation Study Identifies MDM2, FKBP5 and CTNNA1 as Diagnostic Gene Signatures for COPD in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010273