Association of NT-proBNP and sST2 with Diastolic Dysfunction in Cirrhotic Patients and Its Therapeutic Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

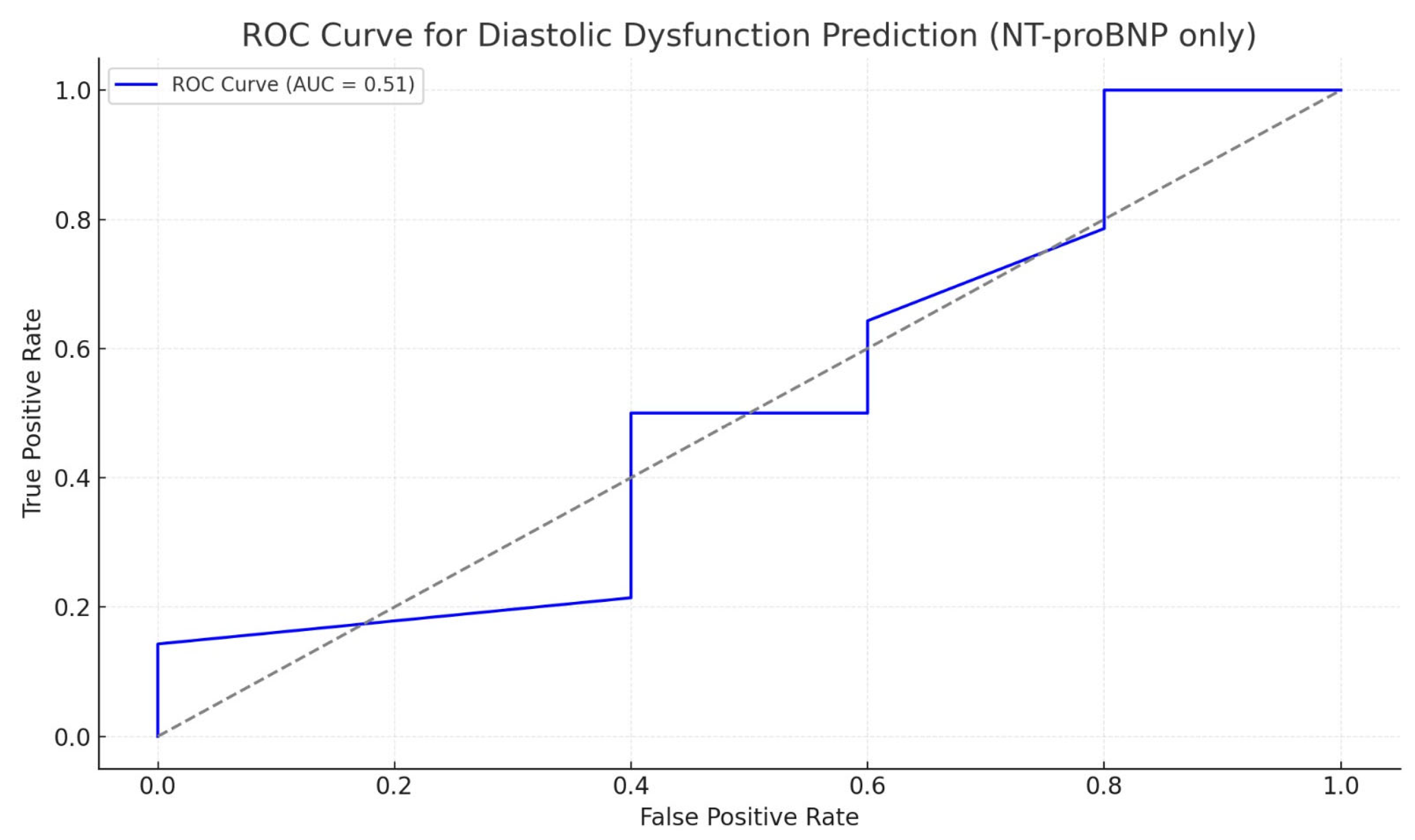

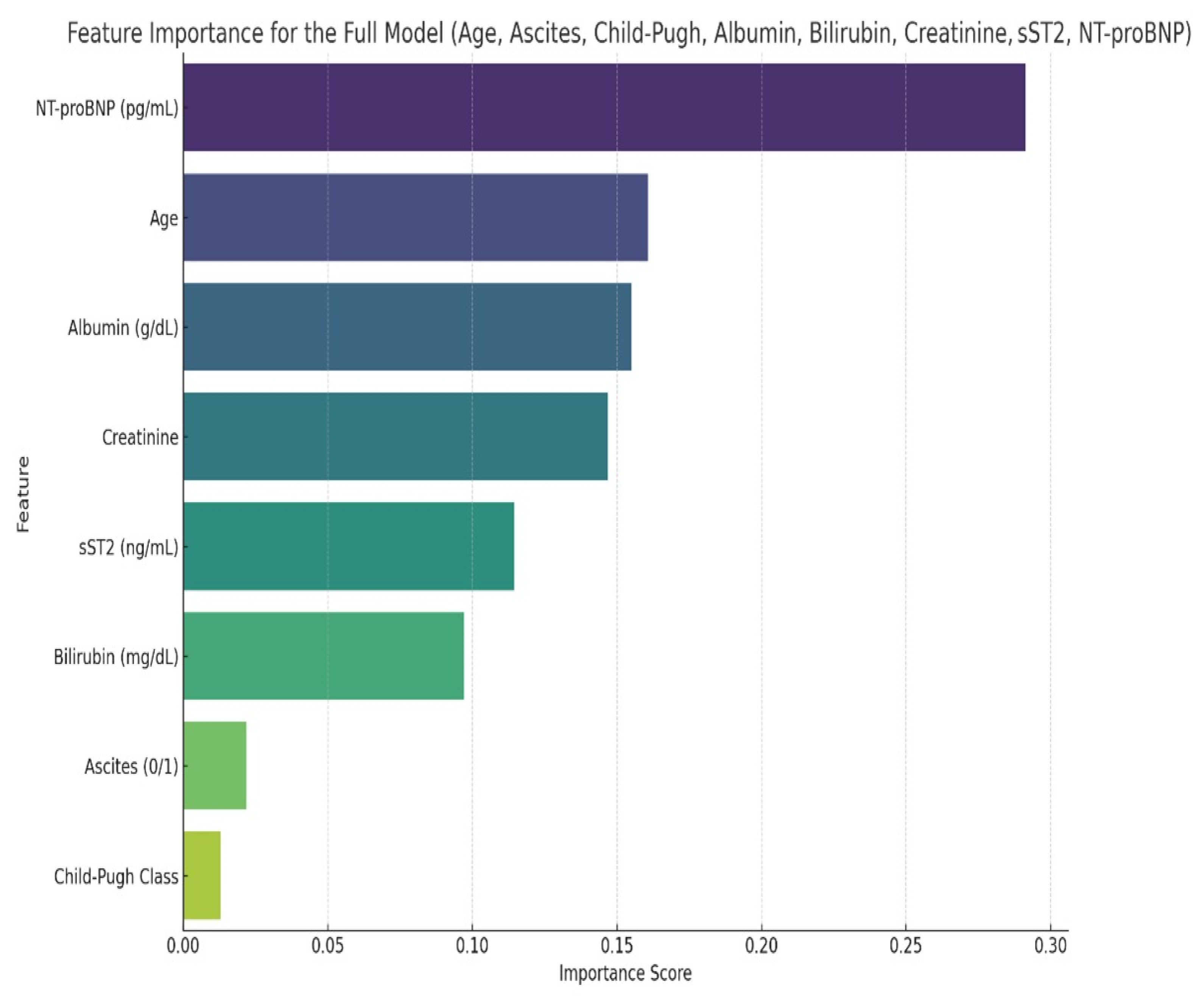

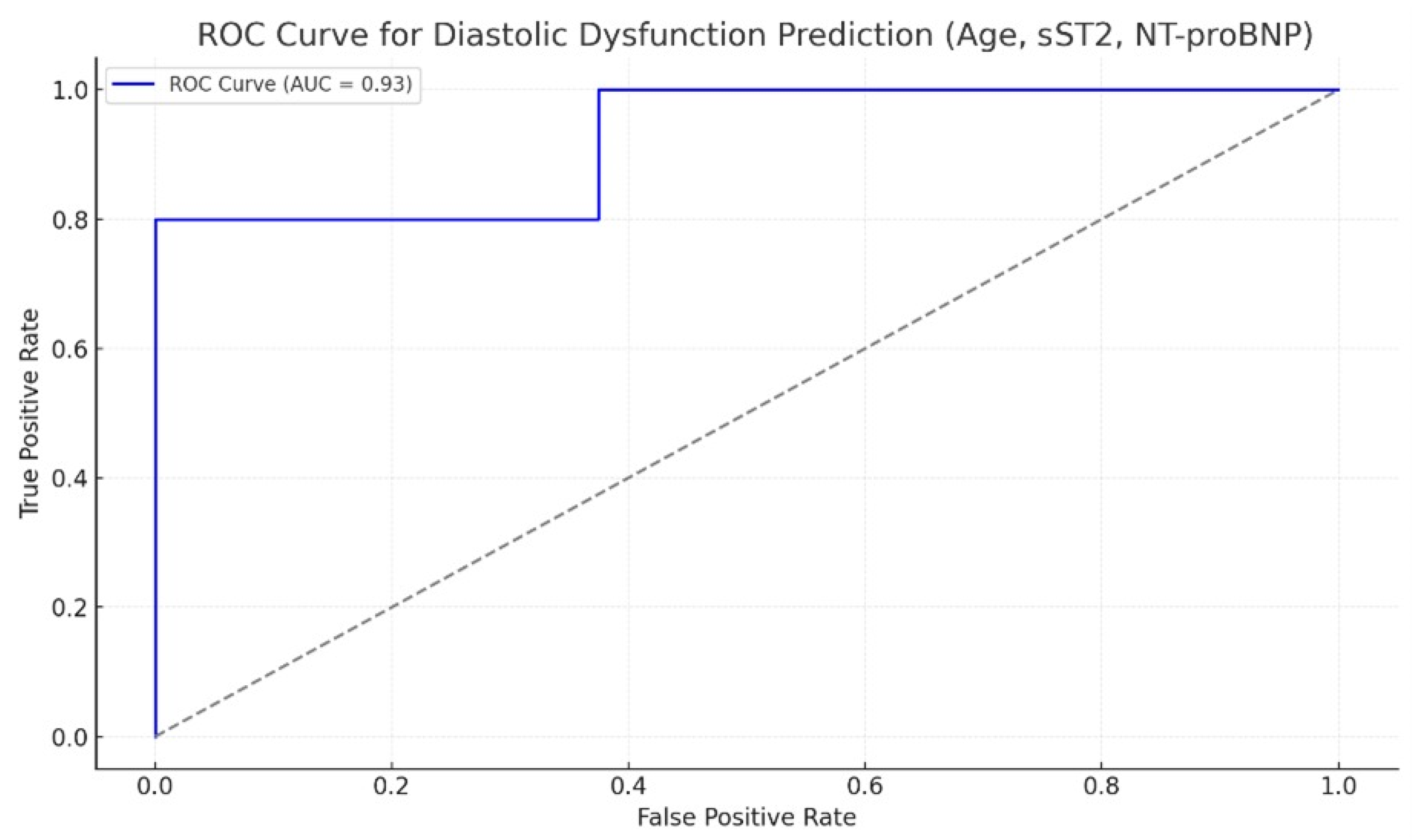

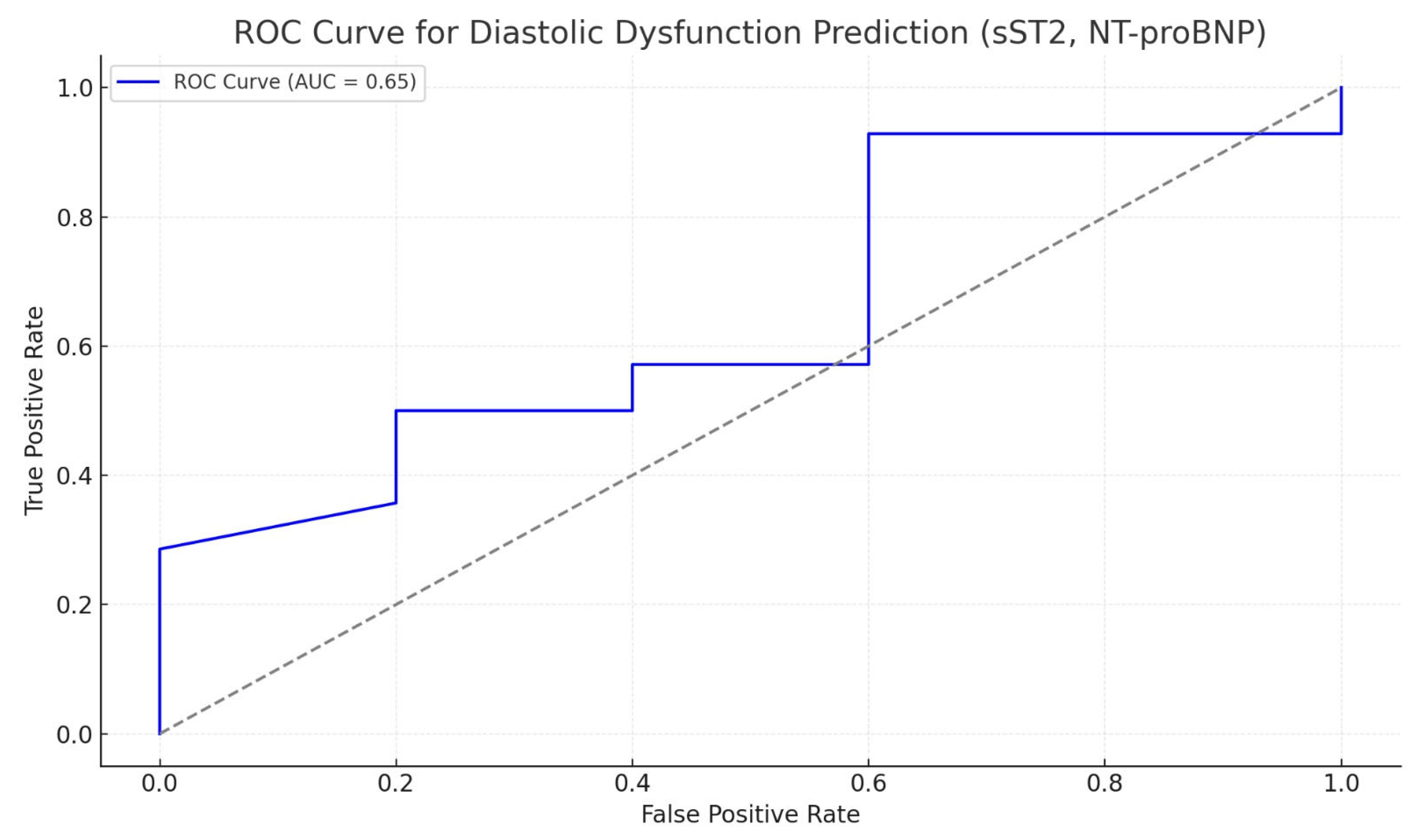

2. Results and Discussions

2.1. Results

2.2. Discussions

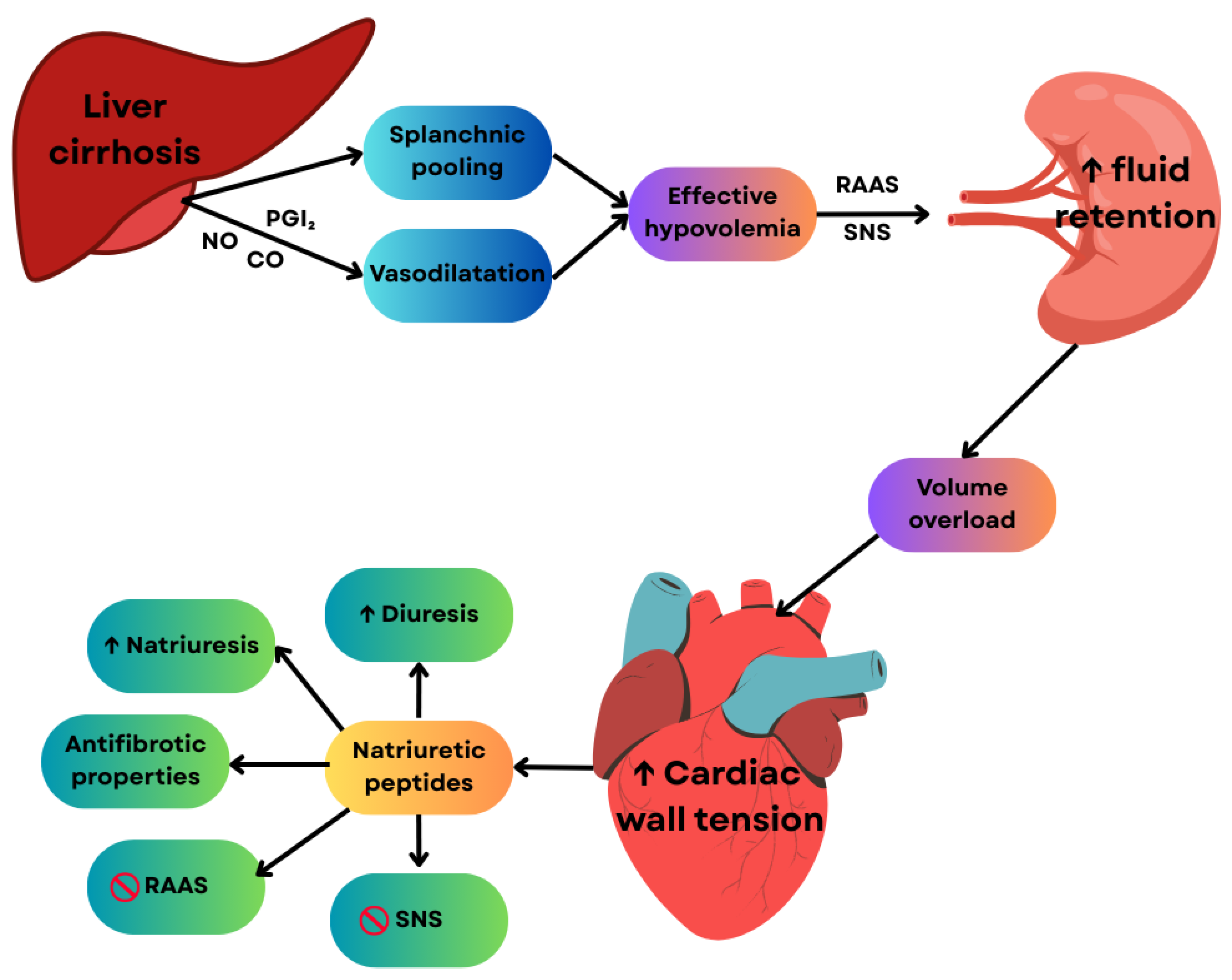

2.2.1. Pathophysiological Significance of NT-proBNP and sST2 in Cirrhotic Cardiomyopathy

2.2.2. Treatment of Cirrhotic Cardiomyopathy: Current Strategies and Biomarker-Based Implications

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Inclusion Criteria: Patients Were Divided into Two Groups

3.3. Exclusion Criteria

3.4. Study Protocol

3.5. Statistical Method

4. Conclusions

Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADH | Antidiuretic Hormone |

| ARNI | Angiotensin Receptor–Neprilysin Inhibitors |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BDL | Bile Duct Ligation |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BNP | B-type Natriuretic Peptide |

| CCM | Cirrhotic Cardiomyopathy |

| cGMP | Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide |

| CW | Continuous Wave (Doppler) |

| E | Early transmitral flow velocity |

| ECCH | Emergency Clinical County Hospital |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| e′ | Early diastolic mitral annular velocity |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| FAC | Fractional Area Change |

| FLIP | Flice-like Inhibitory Protein |

| GLS | Global Longitudinal Strain |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| hs-CRP | High-sensitivity C-Reactive Protein |

| IL-33 | Interleukin 33 |

| INR | International Normalized Ratio |

| LA | Left Atrium/Left Atrial |

| LAVI | Left Atrial Volume Index |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| LV | Left Ventricle/Left Ventricular |

| LVDD | Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction |

| LVEF | Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| LVSD | Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction |

| MHC | Myosin Heavy Chain |

| MR-proANP | Mid-Regional Pro-Atrial Natriuretic Peptide |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NSBBs | Non-selective beta-blockers |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro–B-type Natriuretic Peptide |

| PARP | Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase |

| PW | Pulsed Wave (Doppler) |

| RAAS | Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| RV | Right Ventricle/Right Ventricular |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SNS | Sympathetic Nervous System |

| sST2 | Soluble Suppression of Tumorigenicity 2 |

| TAPSE | Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion |

| TDI | Tissue Doppler Imaging |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| TR | Tricuspid Regurgitation |

| Vmax TR | Maximal Systolic Velocity of Tricuspid Regurgitation |

References

- Yoshiji, H.; Nagoshi, S.; Akahane, T.; Asaoka, Y.; Ueno, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Kawaguchi, T.; Kurosaki, M.; Sakaida, I.; Shimizu, M.; et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for liver cirrhosis 2020. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 593–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.K.; Song, M.J.; Kim, S.H.; Ahn, H.J. Cardiac diastolic dysfunction predicts poor prognosis in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2018, 24, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, H.; Premkumar, M. Diagnosis and management of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2022, 12, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.Q.; Terrault, N.A.; Tacke, F.; Gluud, L.L.; Arrese, M.; Bugianesi, E.; Loomba, R. Global epidemiology of cirrhosis—Aetiology, trends and predictions. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, H.J.; Abelmann, W.H. The cardiac output at rest in Laennec’s cirrhosis. J. Clin. Investig. 1953, 32, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudabbous, M.; Hammemi, R.; Gdoura, H.; Chtourou, L.; Moalla, M.; Mnif, L.; Amouri, A.; Abid, L.; Tahri, N. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy: A subject that is always topical. Future Sci. OA 2024, 10, FSO954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.T.; Liu, H.; Lee, S.S. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2020, 22, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimić, S.; Svaguša, T.; Grgurević, I.; Mustapić, S.; Žarak, M.; Prkačin, I. Markers of cardiac injury in patients with liver cirrhosis. Croat. Med. J. 2023, 64, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farcaş, A.D.; Mocan, M.; Anton, F.P.; Mocan-Hognogi, D.L.; Chiorescu, R.M.; Stoia, M.A.; Vonica, C.L.; Goidescu, C.M.; Vida-Simiti, L.A. Short-term prognosis value of sST2 for an unfavorable outcome in hypertensive patients. Dis. Markers 2020, 2020, 8143737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdin, M.; Aimo, A.; Vergaro, G.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Lupón, J.; Latini, R.; Meessen, J.; Anand, I.S.; Cohn, J.N.; Gravning, J.; et al. sST2 predicts outcome in chronic heart failure beyond NT-proBNP and high-sensitivity troponin T. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2309–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Xie, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, L.; Pan, Y. Changing epidemiology of cirrhosis from 2010 to 2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2252326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Naser, J.A.; Lin, G.; Lee, S.S. Cardiomyopathy in cirrhosis: From pathophysiology to clinical care. JHEP Rep. 2023, 6, 100911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enache, I.; Oswald-Mammosser, M.; Woehl-Jaegle, M.-L.; Habersetzer, F.; Di Marco, P.; Charloux, A.; Doutreleau, S. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy and hepatopulmonary syndrome: Prevalence and prognosis in a series of patients. Respir. Med. 2013, 107, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-del-Árbol, L.; Serradilla, R. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 11502–11521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalheiro, F.; Rodrigues, C.; Adrego, T.; Viana, J.; Vieira, H.; Seco, C.; Pereira, L.; Pinto, F.; Eufrásio, A.; Bento, C.; et al. Diastolic dysfunction in liver cirrhosis: Prognostic predictor in liver transplantation? Transplant. Proc. 2016, 48, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stundienė, I.; Sarnelytė, J.; Norkutė, A.; Aidietienė, S.; Liakina, V.; Masalaitė, L.; Valantinas, J. Liver cirrhosis and left ventricle diastolic dysfunction: A systematic review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 4779–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, S.; Wiese, S.; Halgreen, H.; Hove, J.D. Diastolic dysfunction in cirrhosis. Heart Fail. Rev. 2016, 21, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzy, M.; VanWagner, L.B.; Lin, G.; Altieri, M.; Findlay, J.Y.; Oh, J.K.; Watt, K.D.; Lee, S.S. Cirrhotic Cardiomyopathy Consortium. Redefining cirrhotic cardiomyopathy for the modern era. Hepatology 2020, 71, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Nguyen, H.H.; Yoon, K.T.; Lee, S.S. Pathogenic mechanisms underlying cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. Front. Netw. Physiol. 2022, 2, 849253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Kang, P.; Guo, J.; Zhu, L.; Xu, Q.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. Effects of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 on autophagy-associated proteins in neonatal rat myocardial fibroblasts cultured in high glucose. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2019, 39, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, U.; Behnes, M.; Hoffmann, J.; Natale, M.; Fastner, C.; El-Battrawy, I.; Rusnak, J.; Kim, S.-H.; Lang, S.; Hoffmann, U.; et al. Galectin-3 reflects the echocardiographic grades of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Ann. Lab. Med. 2018, 38, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocan, M.; Hognogi, L.D.M.; Anton, F.P.; Chiorescu, R.M.; Goidescu, C.M.; Stoia, M.A.; Farcas, A.D. Biomarkers of inflammation in left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Dis. Markers 2019, 2019, 7583690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Wu, Q.; Hu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Lee, S.S. Role of anti-beta-1-adrenergic receptor antibodies in cardiac dysfunction in patients with cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2022, 15, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, T.K.; Honar, H.; Liu, H.; ter Keurs, H.E.; Lee, S.S. Role of cardiac myofilament proteins titin and collagen in the pathogenesis of diastolic dysfunction in cirrhotic rats. J. Hepatol. 2011, 55, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Lee, S.S.; Meddings, J.B. Effects of altered cardiac membrane fluidity on beta-adrenergic receptor signalling in rats with cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. J. Hepatol. 1997, 26, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.W.; Liu, H.; Wong, J.Z.; Feng, A.Y.; Chu, G.; Merchant, N.; Lee, S.S. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis contributes to pathogenesis of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy in bile duct-ligated mice. Clin. Sci. 2014, 127, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbadi, D.; Laroumanie, F.; Bizou, M.; Pozzo, J.; Daviaud, D.; Delage, C.; Calise, D.; Gaits-Iacovoni, F.; Dutaur, M.; Tortosa, F.; et al. Local production of tenascin-C acts as a trigger for monocyte/macrophage recruitment that provokes cardiac dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ma, Z.; Lee, S.S. Contribution of nitric oxide to the pathogenesis of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy in bile duct-ligated rats. Gastroenterology 2000, 118, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Sun, L.; Wang, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, Q. Autonomic regulation of imbalance-induced myocardial fibrosis and its mechanism in rats with cirrhosis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Song, D.; Lee, S.S. Role of heme oxygenase–carbon monoxide pathway in pathogenesis of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2001, 280, G68–G74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Jia, Y.; Zhu, B. BNP and NT-proBNP as diagnostic biomarkers for cardiac dysfunction in both clinical and forensic medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C.; McDonald, K.; de Boer, R.A.; Maisel, A.; Cleland, J.G.; Kozhuharov, N.; Coats, A.J.; Metra, M.; Mebazaa, A.; Ruschitzka, F.; et al. Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology practical guidance on the use of natriuretic peptide concentrations. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihailovici, A.R.; Donoiu, I.; Gheonea, D.I.; Mirea, O.; Târtea, G.C.; Buşe, M.; Calborean, V.; Obleagă, C.; Pădureanu, V.; Istrătoaie, O. NT-proBNP and echocardiographic parameters in liver cirrhosis: Correlations with disease severity. Med. Princ. Pract. 2019, 28, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, G.; Rubattu, S.; Autore, C.; Volpe, M. Natriuretic peptides: It is time for guided therapeutic strategies based on their molecular mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, S.; Mortensen, C.; Gøtze, J.P.; Christensen, E.; Andersen, O.; Bendtsen, F.; Møller, S. Cardiac and proinflammatory markers predict prognosis in cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2014, 34, e19–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saner, F.H.; Neumann, T.; Canbay, A.; Treckmann, J.W.; Hartmann, M.; Goerlinger, K.; Bertram, S.; Beckebaum, S.; Cicinnati, V.; Paul, A. High brain natriuretic peptide level predicts cirrhotic cardiomyopathy in liver transplant patients. Transpl. Int. 2011, 24, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutka, M.; Bobiński, R.; Ulman-Włodarz, I.; Hajduga, M.; Bujok, J.; Pająk, C.; Ćwiertnia, M. Various aspects of inflammation in heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2020, 25, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejnovic, N.; Jeftic, I.; Jovicic, N.; Arsenijevic, N.; Lukic, M.L. Galectin-3 and IL-33/ST2 axis roles and interplay in diet-induced steatohepatitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 9706–9717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A.M. ST2 and prognosis in chronic heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2321–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimo, A.; Januzzi, J.L., Jr.; Vergaro, G.; Richards, A.M.; Lam, C.S.P.; Latini, R.; Anand, I.S.; Cohn, J.N.; Ueland, T.; Gullestad, L.; et al. Circulating Levels and Prognostic Value of Soluble ST2 in Heart Failure Are Less Influenced by Age than N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide and High-Sensitivity Troponin T. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 2078–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Franchis, R.; Baveno, V.I.F. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J. Hepatol. 2015, 63, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niaz, Q.; Tavangar, S.M.; Mehreen, S.; Ghazi-Khansari, M.; Jazaeri, F. Evaluation of statins as a new therapy to alleviate chronotropic dysfunction in cirrhotic rats. Life Sci. 2022, 308, 120966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siafarikas, C.; Kapelios, C.J.; Papatheodoridi, M.; Vlachogiannakos, J.; Tentolouris, N.; Papatheodoridis, G. Sodium–glucose linked transporter 2 inhibitors in liver cirrhosis: Beyond their antidiabetic use. Liver Int. 2024, 44, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Ryu, D.; Hwang, S.; Lee, S.S. Therapies for cirrhotic cardiomyopathy: Current perspectives and future possibilities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, H.; Berliner, D.; Stockhoff, L.; Reincke, M.; Mauz, J.B.; Meyer, B.; Bauersachs, J.; Wedemeyer, H.; Wacker, F.; Bettinger, D.; et al. Diastolic dysfunction is associated with cardiac decompensation after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in patients with liver cirrhosis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2023, 11, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheibani, M.; Nezamoleslami, S.; Mousavi, S.E.; Faghir-Ghanesefat, H.; Yousefi-Manesh, H.; Rezayat, S.M.P.D.; Dehpour, A.P.D. Protective effects of spermidine against cirrhotic cardiomyopathy in bile duct-ligated rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2020, 76, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Clària, J.; Amorós, A.; Aguilar, F.; Castro, M.; Casulleras, M.; Acevedo, J.; Duran-Güell, M.; Nuñez, L.; Costa, M.; et al. Effects of albumin treatment on systemic and portal hemodynamics and systemic inflammation in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchendrygina, A.; Rachina, S.; Cherkasova, N.; Suvorov, A.; Komarova, I.; Mukhina, N.; Ananicheva, N.; Gasanova, D.; Sitnikova, V.; Koposova, A.; et al. Colchicine in Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction: Rationale and Design of a Prospective, Randomised, Open-Label, Crossover Clinical Trial. Open Heart 2023, 10, e002360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vida-Simiti, I. Civil Liability of the Doctor; Hamangiu: Bucharest, Romania, 2013; p. 408. [Google Scholar]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Smiseth, O.A.; Appleton, C.P.; Byrd, B.F., III; Dokainish, H.; Edvardsen, T.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Gillebert, T.C.; Klein, A.L.; Lancellotti, P.; et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016, 29, 277–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient Characteristics | Study Lot (n = 43) | Control Lot (n = 40) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (M/F) | 19/24 | 22/18 | NS |

| Age (Years) | 62.66+/−7.55 | 57.6+/−12.75 | NS |

| BMI (kg/mp2) | 28.72+/−3.67 | 29.39+/−3.25 | NS |

| Scor Child-Pugh | |||

| Child A Class (n%) | 30 (76.35) | ||

| Child B Class (n%) | 9 (13.15) | ||

| Child C Class (n%) | 4 (10.5) | ||

| Heart rate (b/min) | 73+/−11 | 55+/−12 | NS |

| Ascites | 11 (25.6%) | - | |

| Splenomegaly | 19 (44%) | - | |

| Encefalopathy | 4 (9.3%) | - | |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.39 ± 1.11 | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.80 ± 0.33 | ||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.72 ± 0.68 | ||

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 94.17 ± 151 | 19.2 ± 5.47 | p < 0.001 |

| sST2 (ng/mL) | 5.4 ± 2.31 | 2.4 ± 0.99 | p < 0.001 |

| Ultrasound Parameters | Study Lot (n = 43 pts) | Control Lot (40) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| E wave (m/s) | 0.67 ± 0.23 | 0.65 ± 0.19 | NS |

| A wave (m/s) | 0.69 ± 0.21 | 0.72 ± 0.17 | NS |

| E/A | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.85 ± 0.43 | NS |

| EDT (ms) | 251 ± 60 | 245 ± 42.7 | NS |

| Lateral e′ ± velocity (cm/s) | 10 ± 3.3 | 11 ± 1.4 | NS |

| Septal e′ velocity (cm/s) | 8.3 ± 2.8 | 8.8 ± 2.9 | NS |

| E/e′ > 14 | 4 (10.52%) | 0 | |

| LAVI (mL/mp) | 40 | 35 | p < 0.05 |

| VmaxSTr > 2.8 m/sec | 6 (15.78%) | 0 | |

| DD | 22 (51%) | 22 (55%) | NS |

| LVDD grade 1 | 15 (34.8%) | 22 (55%) | |

| LVDD grade 2 | 6 (15.78%) | 0 | |

| LVDD grade 3 | 1 (2.63%) | 0 | |

| ECG Parameters | |||

| QTc (ms) | 444.987+/−94.214 | 422.811+/−30.192 | NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chiorescu, R.M.; Ruda, A.; Chira, R.; Nagy, G.; Bințințan, A.; Chiorescu, Ș.; Mocan, M. Association of NT-proBNP and sST2 with Diastolic Dysfunction in Cirrhotic Patients and Its Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010261

Chiorescu RM, Ruda A, Chira R, Nagy G, Bințințan A, Chiorescu Ș, Mocan M. Association of NT-proBNP and sST2 with Diastolic Dysfunction in Cirrhotic Patients and Its Therapeutic Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010261

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiorescu, Roxana Mihaela, Alexandru Ruda, Romeo Chira, Georgiana Nagy, Adriana Bințințan, Ștefan Chiorescu, and Mihaela Mocan. 2026. "Association of NT-proBNP and sST2 with Diastolic Dysfunction in Cirrhotic Patients and Its Therapeutic Implications" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010261

APA StyleChiorescu, R. M., Ruda, A., Chira, R., Nagy, G., Bințințan, A., Chiorescu, Ș., & Mocan, M. (2026). Association of NT-proBNP and sST2 with Diastolic Dysfunction in Cirrhotic Patients and Its Therapeutic Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010261