Cytomegalovirus in Pregnancy: Effects on the Developing Embryo and Fetus, Diagnosis and Treatment: Where to Go Now? A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Congenital CMV (cCMV)

3. Hearing Loss Is the Most Common Neonatal Presentation of cCMV

4. Fetal Brain Damage and Neurological Sequelae Caused by CMV Are the Most Debilitating Complications of cCMV

5. What Are the More Common Neurodevelopmental Difficulties

6. How Can Maternal CMV Infection Be Diagnosed?

7. Can Fetal CMV Infection Be Diagnosed?

8. Can Fetal Infection and Damage Severity Be Predicted?

9. What Are the Ways for Prevention and/or Reduction of Maternal–Fetal CMV Transmission?

9.1. Prevention of Exposure

9.2. Prevention by Cytomegalovirus Hyperimmune Globulin (CMV HIG): A Less Effective Way with Possible Side Effects

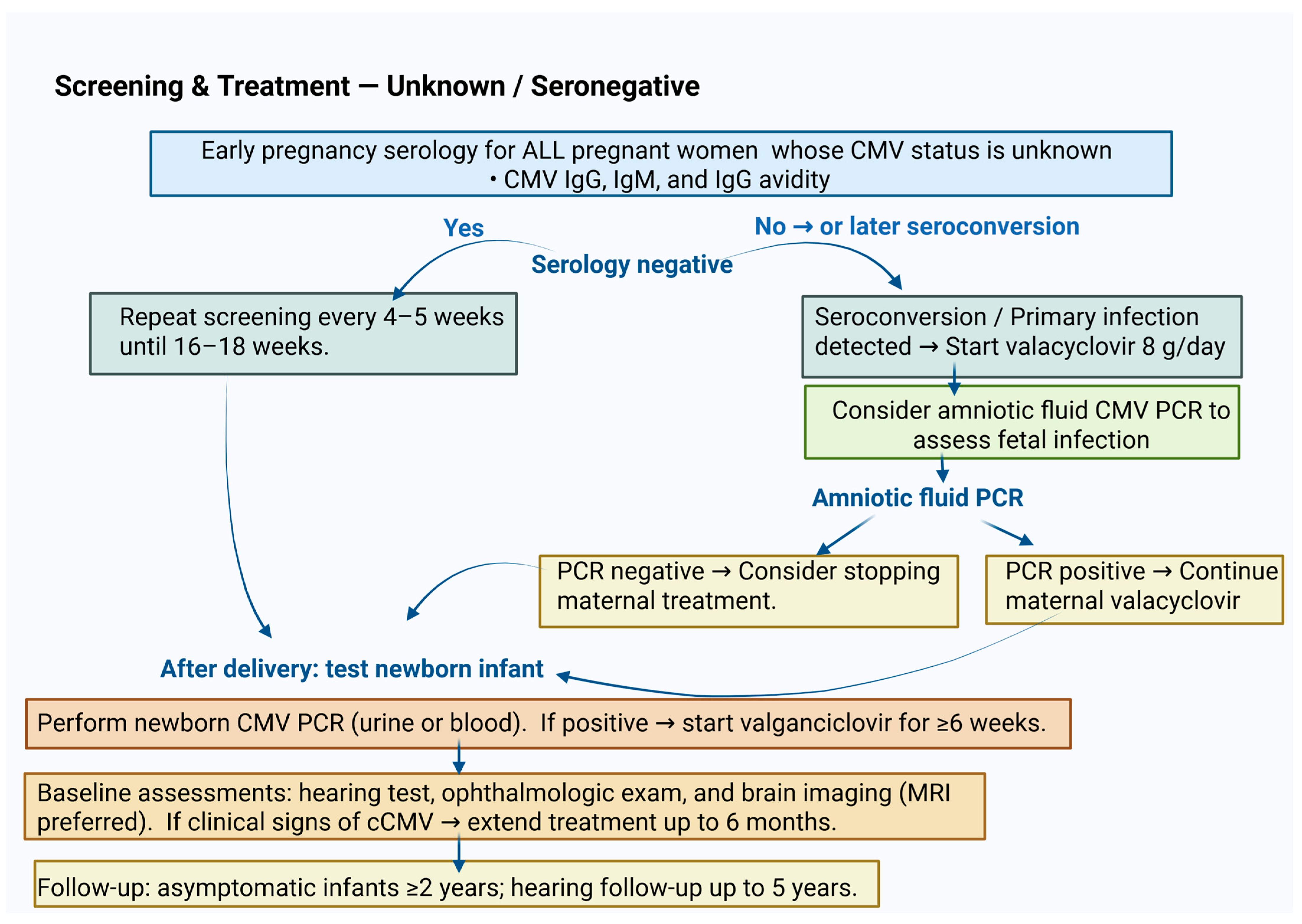

9.3. Reduction in Viral Fetal Transmission by Maternal Treatment with High Doses of Valacyclovir

10. Is There Effective Treatment of Infants with cCMV?

11. Can Postnatal CMV Transmission via Breast Milk Affect the Newborn Infant?

12. Can CMV Infection Be Prevented by Vaccination?

12.1. Unsuccessful Vaccines

12.2. Recent Promising Vaccines, Under Clinical Trials

12.2.1. Virus-like Particle Platform

12.2.2. mRNA Vaccine Platform

13. The Debate Around Routine CMV Screening in Pregnant Women and in Neonates: What Is the Current Evidence and the Preferred Recommendations?

13.1. Screening in Pregnancy

13.2. Screening of Newborn Infants

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| cCMV | Congenital cytomegalic virus |

| pCMV | Postnatal Cytomegalovirus |

| IUGR | Intrauterine Growth Restriction |

| HIG | Hyperimmune Globulin |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| VLBW | Very Low Birth Weight |

| eVLP | Enveloped Virus-Like Particle |

| ADCC | Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity |

References

- Mhandire, D.; Rowland-Jones, S.; Mhandire, K.; Kaba, M.; Dandara, C. Epidemiology of Cytomegalovirus among pregnant women in Africa. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 13, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbi, M.; Binda, S.; Caroppo, S.; Ambrosetti, U.; Corbetta, C.; Sergi, P. A wider role of cytomegalovirus infection in sensorineural hearing loss. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2003, 22, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pultoo, A.; Jankee, H.; Meetoo, G.; Pyndiah, M.N.; Khittoo, G. Detection of cytomegalovirus in urine of hearing impaired and men tally retarded children by PCR and cell culture. J. Commun. Dis. 2000, 32, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pultoo, A.; Meetoo, G.; Pyndiah, M.N.; Khittoo, G. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in Mauritian volunteer blood donors. Indian J. Med. Sci. 2001, 55, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Raxonable, R.R.; Paya, C.V. Herpesvirus infections in trans plant recipients: Current challenges in the clinical management of cytomegalovirus and Epstein–Barr virus infections. Herpes 2003, 10, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ornoy, A.; Diav-Citrin, O. Fetal effects of primary and secondary cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy. Reprod. Toxicol. 2006, 21, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaytant, M.A.; Steegers, E.A.; Semmekrot, B.A.; Merkus, H.M.; Galama, J.M. Congenital cytomegalovirus infections: Review of the epidemiology and outcome. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2002, 57, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoh, A.E.; Murthy, S.; Akoua-Koffi, C.; Couacy-Hymann, E.; Leendertz, F.H.; Calvignac-Spencer, S.; Ehlers, B. Cytomegaloviruses in a Community of Wild Nonhuman Primates in Tai National Park, Cote D’Ivoire. Viruses 2017, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, C.A.; Stagno, S.; Pass, R.F.; Britt, W.J. Congenital and peri natal cytomegalovirus infections. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1990, 12, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotton, C.N.; Kamar, N. New Insights on CMV Management in Solid Organ Transplant Patients: Prevention, Treatment, and Management of Resistant/Refractory Disease. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2023, 12, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, B.; Seibold-Weiger, K.; Schmitz-Salue, C.; Hamprecht, K.; Goelz, R.; Krageloh-Mann, I.; Speer, C.P. Postnatally acquired cytomegalovirus infection via breast milk: Effects on hearing and development in preterm infants. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2004, 23, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Schwebke, I.; Kampf, G. How long do nosocomial pathogens persist on inanimate surfaces? A systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2006, 6, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Shorman, M. Cytomegalovirus Infections. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Faix, R.G. Survival of cytomegalovirus on environmental surfaces. J. Pediatr. 1985, 106, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Suchet, I.; Somerset, D.; de Koning, L.; Chadha, R.; Soliman, N.; Kuret, V.; Yu, W.; Lauzon, J.; Thomas, M.A.; et al. Maternal Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Serology: The Diagnostic Limitations of CMV IgM and IgG Avidity in Detecting Congenital CMV Infection. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2024, 27, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boppana, S.B.; Fowler, K.B.; Britt, W.J.; Stagno, S.; Pass, R.F. Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection in infants born to mothers with preexisting immunity to cytomegalovirus. Pediatrics 1999, 104, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boppana, S.B.; Rivera, L.B.; Fowler, K.B.; Mach, M.; Britt, W.J. Intrauterine transmission of cytomegalovirus to infants of women with preconceptional immunity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 1366–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, M.H.; Mowers, J.; Huynh, A.; Schleiss, M.R. Intrauterine Fetal Demise, Spontaneous Abortion and Congenital Cytomegalovirus: A Systematic Review of the Incidence and Histopathologic Features. Viruses 2024, 16, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssentongo, P.; Hehnly, C.; Birungi, P.; Roach, M.A.; Spady, J.; Fronterre, C.; Wang, M.; Murray-Kolb, L.E.; Al-Shaar, L.; Chinchilli, V.M.; et al. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection Burden and Epidemiologic Risk Factors in Countries with Universal Screening: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2120736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, K.B.; Stagno, S.; Pass, R.F. Maternal age and congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Screening of two diverse newborn populations. J. Infect. Dis. 1993, 168, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneson, A.; Cannon, M.J. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 2007, 17, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahav, G.; Gabbay, R.; Ornoy, A.; Shechtman, S.; Arnon, J.; Diav-Citrin, O. Primary versus nonprimary cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy, Israel. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 1791–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiopris, G.; Veronese, P.; Cusenza, F.; Procaccianti, M.; Perrone, S.; Daccò, V.; Colombo, C.; Esposito, S. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Update on Diagnosis and Treatment. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarotto, T.; Varani, S.; Guerra, B.; Nicolosi, A.; Lanari, M.; Landini, M.P. Prenatal indicators of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J. Pediatr. 2000, 137, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynor, B.D. Cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy. Semin. Perinatol. 1993, 17, 394–402. [Google Scholar]

- Leruez-Ville, M.; Chatzakis, C.; Lilleri, D.; Blazquez-Gamero, D.; Alarcon, A.; Bourgon, N.; Foulon, I.; Fourgeaud, J.; Gonce, A.; Jones, C.E.; et al. Consensus recommendation for prenatal, neonatal and postnatal management of congenital cytomegalovirus infection from the European congenital infection initiative (ECCI). Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 40, 100892, Erratum in Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 42, 100974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.100974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Lee, H.S.; Hui, L.; Schleiss, M.R.; Sung, V. Prenatal and postnatal antiviral therapies for the prevention and treatment of congenital cytomegalovirus infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 37, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzzino, F.; Di Pastena, M.; Chiurchiu, S.; Romani, L.; De Luca, M.; Lucignani, G.; Amodio, D.; Seccia, A.; Marsella, P.; Grimaldi Capitello, T.; et al. Secondary cytomegalovirus infections: How much do we still not know? Comparison of children with symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus born to mothers with primary and secondary infection. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 885926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, K.F.M.; Araujo Junior, E. Cytomegalovirus and pregnancy: Current evidence for clinical practice. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2024, 70, e20240509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salome, S.; Gammella, R.; Coppola, C.; Dolce, P.; Capasso, L.; Blazquez-Gamero, D.; Raimondi, F. Can viral load predict a symptomatic congenital CMV infection? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2025, 184, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, K.B.; Stagno, S.; Pass, R.F. Maternal immunity and prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. JAMA 2003, 289, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, T.; Douvier, S.; Reynaud, I.; Laurent, N.; Bour, J.B.; Durand, C. Severe fatal cytomegalic inclusion disease after docu mented maternal reactivation of cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy. Prenat. Diagn. 2000, 20, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaytant, M.A.; Rours, G.I.; Steegers, E.A.; Galama, J.M.; Semmekrot, B.A. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection after recurrent infection case reports and review of the literature. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2003, 162, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, K.B.; Stagno, S.; Pass, R.F. The outcome of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in relation to maternal antibody status. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 326, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enders, G.; Bader, U.; Lindemann, L.; Schalasta, G.; Daiminger, A. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in 189 pregnancies with known outcome. Prenat. Diagn. 2001, 21, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pass, R.F. Cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatr. Rev. 2002, 23, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, S.A.; Jonsson, K.; Jonsson, B. Birth characteristics and growth pattern in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 16, 1233–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilad, N.; Agrawal, S.; Philippopoulos, E.; Murphy, K.E.; Shinar, S. Is a Higher Amniotic Fluid Viral Load Associated with a Greater Risk of Fetal Injury in Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witters, I.; Ranst, M.; Fryns, J.P. Cytomegalovirus reactivation in pregnancy and subsequent isolated bilateral hearing loss in the infant. Genet. Couns. 2000, 11, 375–378. [Google Scholar]

- Teissier, N.; Delezoide, A.L.; Mas, A.E.; Khung-Savatovsky, S.; Bessieres, B.; Nardelli, J.; Vauloup-Fellous, C.; Picone, O.; Houhou, N.; Oury, J.F.; et al. Inner ear lesions in congenital cytomegalovirus infection of human fetuses. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 122, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, L.; Bonasoni, M.P.; Santini, D.; Piccirilli, G.; Chiereghin, A.; Petrisli, E.; Dolcetti, R.; Guerra, B.; Piccioli, M.; Lanari, M.; et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Patterns of fetal brain damage. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, E419–E427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, L.; Bonasoni, M.P.; Santini, D.; Piccirilli, G.; Chiereghin, A.; Guerra, B.; Landini, M.P.; Capretti, M.G.; Lanari, M.; Lazzarotto, T. Human fetal inner ear involvement in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2013, 1, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, L.; Bonasoni, M.P.; Piccirilli, G.; Petrisli, E.; Venturoli, S.; Cantiani, A.; Pavoni, M.; Marsico, C.; Capretti, M.G.; Simonazzi, G.; et al. The Auditory Pathway in Congenitally Cytomegalovirus-Infected Human Fetuses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craeghs, L.; Goderis, J.; Acke, F.; Keymeulen, A.; Smets, K.; Van Hoecke, H.; De Leenheer, E.; Boudewyns, A.; Desloovere, C.; Kuhweide, R.; et al. Congenital CMV-Associated Hearing Loss: Can Brain Imaging Predict Hearing Outcome? Ear Hear 2021, 42, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hranilovich, J.A.; Park, A.H.; Knackstedt, E.D.; Ostrander, B.E.; Hedlund, G.L.; Shi, K.; Bale, J.F., Jr. Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Congenital Cytomegalovirus With Failed Newborn Hearing Screen. Pediatr. Neurol. 2020, 110, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabani, N.; Pinninti, S.; Boppana, S.; Fowler, K.; Ross, S. Urine and Saliva Viral Load in Children with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2023, 12, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazzi, V.; Hatzopoulos, S.; Bianchini, C.; Skarzynska, M.B.; Pelucchi, S.; Skarzynski, P.H.; Ciorba, A. Vestibular and postural impairment in congenital Cytomegalovirus infection. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 152, 111005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, A.W.; McMullan, B.; Rawlinson, W.D.; Palasanthiran, P. Hearing and neurodevelopmental outcomes for children with asymptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: A systematic review. Rev. Med. Virol. 2017, 27, e1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keymeulen, A.; De Leenheer, E.; Casaer, A.; Cossey, V.; Laroche, S.; Mahieu, L.; Oostra, A.; Van Mol, C.; Dhooge, I.; Smets, K. Neurodevelopmental outcome in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection: A prospective multicenter cohort study. Early Hum. Dev. 2023, 182, 105777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyrli, A.; Raveendran, V.; Walter, S.; Pagarkar, W.; Field, N.; Kadambari, S.; Lyall, H.; Bailey, H. What are the neurodevelopmental outcomes of children with asymptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection at birth? A systematic literature review. Rev. Med. Virol. 2024, 34, e2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, L.S.; Gunardi, H.; Barth, P.G.; Bok, L.A.; Verboon-Maciolek, M.A.; Groenendaal, F. The spectrum of cranial ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Neuropediatrics 2004, 35, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinger, G.; Lev, D.; Lerman-Sagie, T. Imaging of fetal cytomegalovirus infection. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2011, 29, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boppana, S.B.; Fowler, K.B.; Vaid, Y.; Hedlund, G.; Stagno, S.; Britt, W.J. Neuroradiographic findings in the newborn period and long-term outcome in children with symptomatic cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatrics 1997, 99, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyola, D.E.; Demmler, G.J.; Nelson, C.T.; Griesser, C.; Williamson, W.D.; Alkins, J.T. Houston Congenital CMV Longitudinal Study Group. Early predictors of neurodevelopmental outcome in symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J. Pediatr. 2001, 138, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsico, C.; Kimberlin, D.W. Congenital Cytomegalovirus infection: Advances and challenges in diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2017, 43, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damato, E.G.; Winnen, C.W. Cytomegalovirus infection: Perinatal implications. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2002, 31, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, S.A.; Bjerre, I.; Vegfors, P.; Ahlfors, K. Autism as one of several disabilities in two children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Neuropediatrics 1990, 21, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.; Fujimoto, C.; Nakajima, E.; Isagai, T.; Matsuishi, T. Possible association between congenital cytomegalovirus and autistic disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2003, 33, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahle, A.J.; Fowler, K.B.; Wright, J.D.; Boppana, S.B.; Britt, W.J.; Pass, R.F. Longitudinal investigation of hearing disorders in children with congenital cytomegalovirus. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2000, 11, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipitz, S.; Achiron, R.; Zalel, Y.; Mendelson, E.; Tepperberg, M.; Gamzu, R. Outcome of pregnancies with vertical transmission of primary cytomegalovirus infection. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 100, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sonoyama, A.; Ebina, Y.; Morioka, I.; Tanimura, K.; Morizane, M.; Tairaku, S.; Minematsu, T.; Inoue, N.; Yamada, H. Low IgG avidity and ultrasound fetal abnormality predict congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J. Med. Virol. 2012, 84, 1928–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebina, Y.; Minematsu, T.; Sonoyama, A.; Morioka, I.; Inoue, N.; Tairaku, S.; Nagamata, S.; Tanimura, K.; Morizane, M.; Deguchi, M.; et al. The IgG avidity value for the prediction of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in a prospective cohort study. J. Perinat. Med. 2014, 42, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, H.E.; Lape-Nixon, M. Role of cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgG avidity testing in diagnosing primary CMV infection during pregnancy. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2014, 21, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapuan, S.; Theodosiou, A.A.; Strang, B.L.; Heath, P.T.; Jones, C.E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of human cytomegalovirus shedding in seropositive pregnant women. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, e2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z.Z.; Ong, C.; Chan, C.Y.; Yeo, K.T.; Wan, W.Y.; Chan, J.K.Y.; Tan, W.C.; Tan, L.K.; Palasanthiran, P.; Wang, Y.; et al. Single-Step Universal First-Trimester Cytomegalovirus Screening and Valacyclovir Prophylaxis in Pregnancy: A Cost-Utility Analysis in a High Seroprevalence Setting. Prenat. Diagn. 2025, 45, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzarotto, T.; Blazquez-Gamero, D.; Delforge, M.L.; Foulon, I.; Luck, S.; Modrow, S.; Leruez-Ville, M. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: A Narrative Review of the Issues in Screening and Management From a Panel of European Experts. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, J.; Flindt, J.; Pollmann, M.; Saschenbrecker, S.; Borchardt-Loholter, V.; Warnecke, J.M. Efficiency of CMV serodiagnosis during pregnancy in daily laboratory routine. J. Virol. Methods 2023, 314, 114685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, S.M.; Goshia, T.; Sinha, M.; Fraley, S.I.; Williams, M. Decoding human cytomegalovirus for the development of innovative diagnostics to detect congenital infection. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 95, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, A.; Heath, P.T.; Jones, C.E.; Soe, A.; Ville, Y.G.; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Update on Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment: Scientific Impact Paper No. 56. BJOG 2025, 132, e42–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arav-Boger, R.; Pass, R.F. Diagnosis and management of cytomegalovirus infection in the newborn. Pediatr. Ann. 2002, 31, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimura, K.; Yamada, H. Potential Biomarkers for Predicting Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinger, G.; Lev, D.; Zahalka, N.; Ben Aroia, Z.; Watemberg, N.; Kidron, D. Fetal cytomegalovirus infection of the brain: The spectrum of sonographic findings. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2003, 24, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, C.Y.W.; Li, M.; Jonjic, S.; Sanchez, V.; Britt, W.J. Cytomegalovirus infection lengthens the cell cycle of granule cell precursors during postnatal cerebellar development. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e175525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarotto, T.; Gabrielli, L.; Foschini, M.P.; Lanari, M.; Guerra, B.; Eusebi, V. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in twin pregnancies: Viral load in the amniotic fluid and pregnancy outcome. Pediatrics 2003, 112, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, E.; Sarac Sivrikoz, T.; Sarsar, K.; Tureli, D.; Onel, M.; Demirci, M.; Yapar, G.; Yurtseven, E.; Has, R.; Agacfidan, A.; et al. Evaluation of Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection in Pregnant Women Admitted to a University Hospital in Istanbul. Viruses 2024, 16, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorontsov, O.; Levitt, L.; Lilleri, D.; Vainer, G.W.; Kaplan, O.; Schreiber, L.; Arossa, A.; Spinillo, A.; Furione, M.; Alfi, O.; et al. Amniotic fluid biomarkers predict the severity of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J. Clin. Invest. 2022, 132, e157415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, K.B.; Stagno, S.; Pass, R.F. Interval between births and risk of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 1035–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planitzer, C.B.; Saemann, M.D.; Gajek, H.; Farcet, M.R.; Kreil, T.R. Cytomegalovirus neutralization by hyperimmune and standard intravenous immunoglobulin preparations. Transplantation 2011, 92, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, G.; Adler, S.P.; La Torre, R.; Best, A.M.; Congenital Cytomegalovirus Collaborating Group. Passive immunization during pregnancy for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1350–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozawa, N.; Fang-Hoover, J.; Tabata, T.; Maidji, E.; Pereira, L. Cytomegalovirus-specific, high-avidity IgG with neutralizing activity in maternal circulation enriched in the fetal bloodstream. J. Clin. Virol. 2009, 46, S58–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, V.; Hackeloer, M.; Rancourt, R.C.; Henrich, W.; Siedentopf, J.P. Fetal and maternal outcome after hyperimmunoglobulin administration for prevention of maternal-fetal transmission of cytomegalovirus during pregnancy: Retrospective cohort analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 302, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, K.O.; Enders, M.; Hoopmann, M.; Geipel, A.; Simonini, C.; Berg, C.; Gottschalk, I.; Faschingbauer, F.; Schneider, M.O.; Ganzenmueller, T.; et al. Outcome of pregnancies with recent primary cytomegalovirus infection in first trimester treated with hyperimmunoglobulin: Observational study. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 57, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, K.O.; Enders, M.; Schampera, M.S.; Baeumel, E.; Hoopmann, M.; Geipel, A.; Berg, C.; Goelz, R.; De Catte, L.; Wallwiener, D.; et al. Prevention of maternal-fetal transmission of cytomegalovirus after primary maternal infection in the first trimester by biweekly hyperimmunoglobulin administration. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 53, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazquez-Gamero, D.; Galindo Izquierdo, A.; Del Rosal, T.; Baquero-Artigao, F.; Izquierdo Mendez, N.; Soriano-Ramos, M.; Rojo Conejo, P.; Gonzalez-Tome, M.I.; Garcia-Burguillo, A.; Perez Perez, N.; et al. Prevention and treatment of fetal cytomegalovirus infection with cytomegalovirus hyperimmune globulin: A multicenter study in Madrid. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019, 32, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revello, M.G.; Lazzarotto, T.; Guerra, B.; Spinillo, A.; Ferrazzi, E.; Kustermann, A.; Guaschino, S.; Vergani, P.; Todros, T.; Frusca, T.; et al. A randomized trial of hyperimmune globulin to prevent congenital cytomegalovirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1316–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, B.L.; Clifton, R.G.; Rouse, D.J.; Saade, G.R.; Dinsmoor, M.J.; Reddy, U.M.; Pass, R.; Allard, D.; Mallett, G.; Fette, L.M.; et al. A Trial of Hyperimmune Globulin to Prevent Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Brentjens, M.H.; Torres, G.; Yeung-Yue, K.; Lee, P.; Tyring, S.K. Valacyclovir in the treatment of herpes simplex, herpes zoster, and other viral infections. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2003, 7, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammarchi, L.; Tomasoni, L.R.; Liuzzi, G.; Simonazzi, G.; Dionisi, C.; Mazzarelli, L.L.; Seidenari, A.; Maruotti, G.M.; Ornaghi, S.; Castelli, F.; et al. Treatment with valacyclovir during pregnancy for prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus infection: A real-life multicenter Italian observational study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, S.; Said Khan, F.; Ishaq Mujeeb Ur Rehman, M.; Akram, M.; Riaz, M.; Rasool, G.; Hamid Khan, A.; Saleem, I.; Shamim, S.; Malik, A. A review: Mechanism of action of antiviral drugs. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2021, 35, 20587384211002621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bras, A.P.; Sitar, D.S.; Aoki, F.Y. Comparative bioavailability of acyclovir from oral valacyclovir and acyclovir in patients treated for recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infection. Can. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001, 8, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kimberlin, D.F.; Weller, S.; Whitley, R.J.; Andrews, W.W.; Hauth, J.C.; Lakeman, F.; Miller, G. Pharmacokinetics of oral valacyclovir and acyclovir in late pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 179, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar-Nissan, K.; Pardo, J.; Peled, O.; Krause, I.; Bilavsky, E.; Wiznitzer, A.; Hadar, E.; Amir, J. Valaciclovir to prevent vertical transmission of cytomegalovirus after maternal primary infection during pregnancy: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 779–785, Erratum in Lancet 2020, 396, 1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32075-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak-Krzyszkowska, M.; Gorecka, J.; Huras, H.; Massalska-Wolska, M.; Staskiewicz, M.; Gach, A.; Kondracka, A.; Staniczek, J.; Gorczewski, W.; Borowski, D.; et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection in Pregnancy Prevention and Treatment Options: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Viruses 2023, 15, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egloff, C.; Sibiude, J.; Vauloup-Fellous, C.; Benachi, A.; Bouthry, E.; Biquard, F.; Hawkins-Villarreal, A.; Houhou-Fidouh, N.; Mandelbrot, L.; Vivanti, A.J.; et al. New data on efficacy of valacyclovir in secondary prevention of maternal-fetal transmission of cytomegalovirus. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 61, 59–66, Correction in Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 61, 541. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.26195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemard, F.; Yamamoto, M.; Costa, J.M.; Romand, S.; Jaqz-Aigrain, E.; Dejean, A.; Daffos, F.; Ville, Y. Maternal administration of valaciclovir in symptomatic intrauterine cytomegalovirus infection. BJOG 2007, 114, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leruez-Ville, M.; Ville, Y. Fetal cytomegalovirus infection. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 38, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.L.; Kendall, G.S.; Edwards, S.; Pandya, P.; Peebles, D.; Nastouli, E.; UCL cCMV MDT. Screening policies for cytomegalovirus in pregnancy in the era of antivirals. Lancet 2022, 400, 489–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Duran, M.A.; Maiz, N.; Liutsko, L.; Bielsa-Pascual, J.; Garcia-Sierra, R.; Zientalska, A.M.; Velasco, I.; Vazquez, E.; Gracia, O.; Ribas, A.; et al. Universal screening programme for cytomegalovirus infection in the first trimester of pregnancy: Study protocol for an observational multicentre study in the area of Barcelona (CITEMB study). BMJ Open 2023, 13, e071997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberlin, D.W.; Lin, C.Y.; Sanchez, P.J.; Demmler, G.J.; Dankner, W.; Shelton, M. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Dis eases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. Effect of ganciclovir therapy on hearing in symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus dis ease involving the central nervous system: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Pediatr. 2003, 143, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, M.G.; Greenbergs, D.P.; Sabo, D.L.; Wald, E.R. Treatment of children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection with gan ciclovir. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2003, 22, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barampouti, F.; Rajan, M.; Aclimandos, W. Should active CMV retinitis in non-immunocompromised newborn babies be treated? Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 248–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberlin, D.W.; Jester, P.M.; Sanchez, P.J.; Ahmed, A.; Arav-Boger, R.; Michaels, M.G.; Ashouri, N.; Englund, J.A.; Estrada, B.; Jacobs, R.F.; et al. Valganciclovir for symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbins, G.C.; Kimberlin, D.W.; Ross, S.A. Cytomegalovirus variation among newborns treated with valganciclovir. Antivir. Res. 2022, 203, 105326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterholm, E.A.; Schleiss, M.R. Impact of breast milk-acquired cytomegalovirus infection in premature infants: Pathogenesis, prevention, and clinical consequences? Rev. Med. Virol. 2020, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Hu, W.; Sun, X.; Chen, L.; Luo, X. Transmission of cytomegalovirus via breast milk in low birth weight and premature infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Han, Y.S.; Sung, T.J.; Kim, D.H.; Kwak, B.O. Clinical presentation and transmission of postnatal cytomegalovirus infection in preterm infants. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 1022869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Kim, S.; Kwak, E.; Park, Y. Routine breast milk monitoring using automated molecular assay system reduced postnatal CMV infection in preterm infants. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1257124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.W.; Cho, M.H.; Bae, S.H.; Lee, R.; Kim, K.S. Incidence of Postnatal CMV Infection among Breastfed Preterm Infants: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021, 36, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.Y.; El-Hamdi, N.S.; McGregor, A. Inclusion of the Viral Pentamer Complex in a Vaccine Design Greatly Improves Protection Against Congenital Cytomegalovirus in the Guinea Pig Model. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01442-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia, S.; Gill, R.B.; Dowdell, K.C.; Wang, Y.; Hornung, R.; Bowman, J.J.; Lacayo, J.C.; Cohen, J.I. Comparison of vaccination with rhesus CMV (RhCMV) soluble gB with a RhCMV replication-defective virus deleted for MHC class I immune evasion genes in a RhCMV challenge model. Vaccine 2019, 37, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, S.A.; Furukawa, T.; Zygraich, N.; Huygelen, C. Candi date cytomegalovirus strain for human vaccination. Infect. Immun. 1975, 12, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, S.P.; Starr, S.E.; Plotkin, S.A.; Hempfling, S.H.; Buis, J.; Manning, M.L. Immunity induced by primary human cytomegalovirus infection protects against secondary infection among women of childbearing age. J. Infect. Dis. 1995, 171, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungman, P.; Bermudez, A.; Logan, A.C.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A.; Chevallier, P.; Martino, R.; Wulf, G.; Selleslag, D.; Kakihana, K.; Langston, A.; et al. A randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ASP0113, a DNA-based CMV vaccine, in seropositive allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplant recipients. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 33, 100787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, V.C. Vaccination against cytomegalovirus: Still at base camp? Am. J. Transplant. 2018, 18, 2847–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, J.M.; Gantt, S.; Halperin, S.A.; Ward, B.; McNeil, S.; Ye, L.; Cai, Y.; Smith, B.; Anderson, D.E.; Mitoma, F.D. An enveloped virus-like particle alum-adjuvanted cytomegalovirus vaccine is safe and immunogenic: A first-in-humans Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) study. Vaccine 2024, 42, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permar, S.R.; Schleiss, M.R.; Plotkin, S.A. A vaccine against cytomegalovirus: How close are we? J. Clin. Invest. 2025, 135, e182317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akingbola, A.; Adegbesan, A.; Adewole, O.; Adegoke, K.; Benson, A.E.; Jombo, P.A.; Uchechukwu Eboson, S.; Oluwasola, V.; Aiyenuro, A. The mRNA-1647 vaccine: A promising step toward the prevention of cytomegalovirus infection (CMV). Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2025, 21, 2450045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fierro, C.; Brune, D.; Shaw, M.; Schwartz, H.; Knightly, C.; Lin, J.; Carfi, A.; Natenshon, A.; Kalidindi, S.; Reuter, C.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a Messenger RNA-Based Cytomegalovirus Vaccine in Healthy Adults: Results From a Phase 1 Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, e668–e678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Karthigeyan, K.P.; Herbek, S.; Valencia, S.M.; Jenks, J.A.; Webster, H.; Miller, I.G.; Connors, M.; Pollara, J.; Andy, C.; et al. Human Cytomegalovirus mRNA-1647 Vaccine Candidate Elicits Potent and Broad Neutralization and Higher Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity Responses Than the gB/MF59 Vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canfield, D.; Gabby, L.; Vaziri Fard, E.; Gyamfi-Bannerman, C. Cytomegalovirus in Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 50, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Tripathi, T.; Holmes, N.E.; Hui, L. Serological screening for cytomegalovirus during pregnancy: A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements. Prenat. Diagn. 2023, 43, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinet, P.; Subtil, D.; Houfflin-Debarge, V.; Kacet, N.; Dewilde, A.; Puech, F. Routine CMV screening during pregnancy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2004, 114, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantos, P.M.; Gantt, S.; Janko, M.; Dionne, F.; Permar, S.R.; Fowler, K. A Geographically Weighted Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Newborn Cytomegalovirus Screening. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofae311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleiss, M.R.; Blázquez-Gamero, D. Universal newborn screening for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2025, 9, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study/Author | Main Findings | Implication for Hearing |

|---|---|---|

| Teissier et al. (2011) [40] | CMV-infected inner ear structures in all fetuses studied, with infection severity correlating with CNS damage. | Disruption of potassium homeostasis in the inner ear may drive sensory cell degeneration and result in SNHL. |

| Gabrielli et al. (2013) [42] | CMV infected the inner ear in 45% of fetuses, especially the stria vascularis and organ of Corti. | Inner ear infection can lead to SNHL even in the absence of brain ultrasound abnormalities. |

| Bartlett et al. (2017) [48] | Asymptomatic infants exhibited 7–11% hearing loss compared with 34–41% in symptomatic infants. | No reliable viral marker predicts outcome; consistent follow-up until school age is recommended for both symptomatic and asymptomatic children. |

| Hranilovich et al. (2020) [45] | MRI abnormalities were significantly associated with failed newborn hearing screening and early onset hearing loss. | Brain MRI should be considered part of the evaluation of infants with cCMV, even if asymptomatic at birth. |

| Craeghs et al. (2021) [44] | Brain abnormalities correlate with early hearing loss (84% specificity, 43% sensitivity). | Neuroimaging can identify infants at risk for early hearing loss. |

| Corazziet al. (2022) [47] | Children with cCMV often show vestibular and postural disorders. | Vestibular impairment can occur independently of hearing loss, underscoring the importance of assessing both systems. |

| Kabani et al. (2023) [46] | Viral load in urine and saliva is higher in symptomatic infants | Viral load alone is insufficient to predict hearing loss. |

| Keymeulen et al. (2023) [49] | Hearing loss occurred in 29.2% of asymptomatic children and in 70.8% of the symptomatic children. Only 70.4% of CMV-infected children had normal development. | Neurodevelopmental issues, including hearing problems, can emerge later. All children with cCMV should receive multidisciplinary neurodevelopmental follow-up. |

| Smyrli et al. (2024) [50] | Among children asymptomatic at birth, 10-15% developed neurodevelopmental disorders, most commonly SNHL. | The risk of hearing loss in asymptomatic infants is relatively low, but long-term surveillance remains advisable. |

| Gabrielli et al. (2024) [43] | CMV showed tropism for the auditory pathway, infecting the stria vascularis and activating microglia in the auditory cortex, especially in cases with high brain viral load. | Both peripheral (cochlear) and central (cortical) auditory damage may contribute to CMV-related SNHL. |

| Study/Author | Main Findings | Implication for Neurodevelopment |

|---|---|---|

| Ivarsson et al. (1990) [57] | Case report of two children with congenital CMV infection who had severe disabilities, including autism. | The study suggests that autism may be among the neurodevelopmental sequelae of severe cCMV infection. |

| Boppana et al. (1997) [53] | Among 56 symptomatic cCMV-infected newborns, 70% had abnormal cranial CT scans. 90% of these developed at least one neurodevelopmental sequela. | Abnormal newborn cranial CT is a strong predictor of later neurodevelopmental impairment in symptomatic cCMV, whereas clinical signs alone are unreliable for prognosis. |

| Noyola et al. (2001) [54] | In children with symptomatic cCMV, microcephaly and abnormal cranial CT at birth were strong predictors of later intellectual and motor disability. | Microcephaly and abnormal neonatal brain imaging strongly predict poor neurodevelopmental outcome. Early head circumference and CT findings can guide prognosis and intervention. |

| Lipitz et al. (2002) [60] | Among 18 live-born infants with confirmed cCMV, 4 had neurological abnormalities; 3 of these had normal prenatal ultrasound. | Normal prenatal ultrasound does not exclude risk of later neurologic impairment. Long-term neurodevelopmental follow-up is warranted even in apparently normal cCMV cases. |

| Yamashita et al. (2003) [58] | Out of 7 children with symptomatic cCMV, 2 (28.6%) were later diagnosed with autism with global developmental delays with MRI evidence of impaired myelination. | Findings suggest a potential association between cCMV-related brain injury and subsequent ASD. |

| Bartlett et al. (2017) [48] | Children with asymptomatic cCMV performed similarly to healthy controls on standardized neurodevelopmental assessments. | Despite overall good outcomes, long-term neurodevelopmental follow-up is recommended as no reliable marker predicts later sequelae. |

| Craeghs et al. (2021) [44] | Brain MRI was useful for predicting early neurological risk, though not definitive for long-term outcomes. | Even with normal early imaging, continued neurodevelopmental surveillance is essential. |

| Keymeulen et al. (2023) [49] | In a cohort of 753 children with cCMV, 29.6% had some level of neurodevelopmental impairment. Adverse outcomes were seen in both symptomatic (53.5%) and asymptomatic (17.8%) children. | Neurodevelopmental follow-up is essential for all cCMV-infected children, with particular attention to hypotonia, ASD and speech delays—even in the absence of hearing loss. |

| Smyrli et al. (2024) [50] | A low rate of children asymptomatic at birth still showed neurodevelopmental impairments later in life. | All cCMV-exposed children should receive long-term neurodevelopmental follow-up. |

| Salome et al. (2025) [30] | Higher maternal blood CMV viral load was associated with more severe neonatal disease and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. | Maternal viral load could be used as an early indicator for identifying infants at risk of neurodevelopmental sequelae, and may serve as an early biomarker for risk stratification. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ornoy, A.; Weinstein-Fudim, L. Cytomegalovirus in Pregnancy: Effects on the Developing Embryo and Fetus, Diagnosis and Treatment: Where to Go Now? A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010252

Ornoy A, Weinstein-Fudim L. Cytomegalovirus in Pregnancy: Effects on the Developing Embryo and Fetus, Diagnosis and Treatment: Where to Go Now? A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010252

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrnoy, Asher, and Liza Weinstein-Fudim. 2026. "Cytomegalovirus in Pregnancy: Effects on the Developing Embryo and Fetus, Diagnosis and Treatment: Where to Go Now? A Narrative Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010252

APA StyleOrnoy, A., & Weinstein-Fudim, L. (2026). Cytomegalovirus in Pregnancy: Effects on the Developing Embryo and Fetus, Diagnosis and Treatment: Where to Go Now? A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010252