Prophage φEr670 and Genomic Island GI_Er147 as Carriers of Resistance Genes in Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Basic Genomic Analyses, ST Determination and Detection of Resistance Genes

2.2. Detection of Prophage Regions

| Taxonomic Group | Strain | Prophage Size [kb] | Resistance Genes Located Within Prophage Regions | Homology with Phage φEr670 | Ortho ANI Value [%] | GenBank Acc. No. | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Query Cover [%] | Similarity [%] | |||||||

| E.rhusiopathiae (prophageφEr670) | 670 | 53 | lsaE, lnuB | NA | NA | 100 | CP183044.1 | This study |

| E. rhusiopathiae (prophage φ1605) | ZJ | 90 | mef(A), msr(D), lnu(D)-like, tetM | 63 | 92.7 | 87.8 | MF172979.1 | [9] |

| E. rhusiopathiae | EMAI_29 | 51 | mph(B) | 71 | 94.2 | 94.9 | JARGDV010000003.1 | [17] |

| E. rhusiopathiae | EMAI_31 | ~52 | msr(D), erm(G) | 76 | 95.2 | ND | JAQTEO010000002.1 | [17] |

| E. rhusiopathiae | EMAI_31 | ~52 | mph(B) | 70 | 95.3 | 94.4 | JAQTEO010000011.1 | [17] |

| E. rhusiopathiae | EMAI_33 | 51 | mph(B) | 70 | 95.3 | 94.4 | JAQTEM010000002.1 | [17] |

| E. rhusiopathiae | EMAI_91 | 53 | lsaE, lnuB | 82 | 94.4 | 94.5 | JAQTCI010000002.1 | [17] |

| E. rhusiopathiae | EMAI_92 | 54 | spw, ant(6)-Ia, mef(A) | 72 | 94.9 | 95.1 | JAQTCH010000002.1 | [17] |

| E. rhusiopathiae | EMAI_141 | 53.5 | lsaE, lnuB | 78 | 94.7 | 95.1 | JAQTAO010000004.1 | [17] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | B3129 | 54.5 | spw, ant(6)-Ia | 75 | 95.0 | 95.1 | SRR2085573 | UN |

| E.rhusiopathiae | B3142 | 54.5 | spw, ant(6)-Ia | 75 | 95.0 | 95.1 | SRR2085574 | UN |

| E.rhusiopathiae | B5577 | 54 | spw, ant(6)-Ia | 75 | 95.3 | 95.1 | SRR2085578 | UN |

| E.rhusiopathiae | B3143 | 54 | spw, ant(6)-Ia | 93 | 95.0 | 95.3 | SRR2085575 | UN |

| E.rhusiopathiae | B3144 | 50 | none | 72 | 92.1 | 92.7 | SRR2085576 | UN |

| E.rhusiopathiae | B3159 | 51 | lsaE, lnuB | 81 | 91.4 | 91.5 | SRR2085577 | UN |

| E.rhusiopathiae | G2 | 52.5 | lsaE, lnuB | 89 | 94.6 | 94.7 | SRR2085593 | UN |

| E.rhusiopathiae | 2604 | 51 | lsaE, lnuB | 78 | 94.7 | 94.7 | SRR2085518 | UN |

| E.rhusiopathiae | 2628 | 52 | lsaE, lnuB | 82 | 95.2 | 95.4 | SRR2085520 | UN |

| E.rhusiopathiae | 2860 | 53 | lsaE, lnuB | 78 | 94.3 | 94.4 | SRR2085522 | UN |

| E.rhusiopathiae | 6028 | 53 | lsaE, lnuB | 78 | 94.6 | 94.5 | SRR2085524 | UN |

| E.rhusiopathiae | 6106 | 52 | lsaE, lnuB | 80 | 91.9 | 91.8 | SRR2085525 | UN |

| E.rhusiopathiae | Chiba 91 | 59 | spw, ant(6)-Ia, tetM | 73 | 92.7 | 92.9 | DRR035665 | [18] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | Saitama 91 | 59 | spw, ant(6)-Ia, tetM | 73 | 92.7 | 92.9 | DRR035666 | [18] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | Chiba 92A | 59 | spw, ant(6)-Ia, tetM | 73 | 92.7 | 92.9 | DRR035667 | [18] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | Chiba 92B | 56.5 | spw, ant(6)-Ia, tetM | 73 | 94.1 | 94.7 | DRR035668 | [18] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | Chiba 93 | 59 | spw, ant(6)-Ia, tetM | 73 | 92.7 | ND | DRR035669 | [18] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | Kanagawa 95 | 58 | spw, ant(6)-Ia, tetM | 73 | 92.7 | ND | DRR035671 | [18] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | Nagano 98 | 59 | spw, ant(6)-Ia, tetM | 73 | 92.7 | 94 | DRR035672 | [18] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | Saitama 01 | 59 | spw, ant(6)-Ia, tetM | 73 | 92.7 | ND | DRR035675 | [18] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | 16BKT031005 | 55 | ermG, msr(D), tetM | 72 | 94.0 | ND | ERR3932976 | [19] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | 16BKT031013 | 51.5 | lnuB, lsaE | 82 | 95.7 | 95.3 | ERR3932981 | [19] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | 16BKT31009 | 54 | lnuB, lsaE | 77 | 94.8 | ND | ERR3932985 | [19] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | 17MIK0642341 | 52 | none | 73 | 94.6 | 94.7 | ERR3932998 | [19] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | 17MIK0642351 | 54.5 | spw, ant(6)-Ia | 75 | 95.0 | ND | ERR3932999 | [19] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | 17MIK0642361 | 51.5 | lnuB, lsaE | 82 | 95.2 | 95.4 | ERR3933000 | [19] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | 17MIK0642371 | 54.5 | spw, ant(6)-Ia | 75 | 95.0 | ND | ERR3933001 | [19] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | swine100 | 52 | spw, ant(6)-Ia | 77 | 96.1 | 97.2 | ERR3678831 | [20] |

| E.rhusiopathiae | swine29 | 55 | spw, ant(6)-Ia, mefA | 72 | 93.4 | ND | ERR3678845 | [20] |

| Erysipelothrix larvae | LV19 | ~59 | none | 76 | 94.4 | ND | CP013213.1 | [21] |

| Thomasclavelia ramosa | DFI.6.112 | 53 | none | 72 | 94.9 | 94.2 | JANGCB010000009.1 | UN |

| Thomasclavelia ramosa | DFI.6.30 | 53 | none | 72 | 94.9 | 94.2 | JAJCKK010000013.1 | UN |

| Streptococcus uberis (prophage Javan630) | C8329 | 52 | lsaE, lnuB, spw, ant(6)-Ia | 77 | 95.5 | 94.8 | JATG01000004.1 | UN |

| Anaerotignum sp. | MB30-C6 | ND | lsaE, lnuB | 81 | 95.6 | 94.6 | CP133078.1 | [22] |

| Eubacterium callanderi | DSM 2594 | ND | none | 74 | 94.6 | ND | CP132136.1 | [23] |

| Eubacterium callanderi | DSM 2593 | ND | none | 74 | 94.6 | ND | CP132135.1 | [23] |

| Eubacterium limosum | EI1405 | 57 | none | 75 | 93.7 | 94.2 | CP171347.1 | UN |

| Eubacterium limosum | DFI.6.107 | 54 | none | 72 | 93.9 | 94.1 | JAJCLO010000002.1 | UN |

| Listeria monocytogenes | N24-0306 | 56 | none | 69 | 89.9 | 88.3 | CP168809.1 | [24] |

| Blautia producta | PMF-1 | ND | mef(A) | 82 | 95.2 | ND | CP035945.1 | UN |

| Clostridiaceae bacterium | HFYG-1003 | ND | mef(A), msr(D) | 71 | 94.6 | ND | CP102060.1 | UN |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 2002127 | 58 | ant(6)-Ia | 74 | 92.6 | 90.1 | ABRTHB010000042.1 | UN |

| Listeria innocua | 2022-1507-16 | 54 | none | 72 | 94.8 | ND | ABTHAP010000005.1 | UN |

| Listeria innocua | A33341 | 54 | mef(A), msr(D), vat-like | 76 | 95.6 | 94.8 | DABKOZ010000007.1 | [25] |

| Listeria innocua | 24MDFML00 6584B | ND | none | 72 | 93.6 | ND | ABTFHD010000005.1 | UN |

| Listeria innocua | fattening pig | 54 | mph(B), vat-like, lnu(J)-like | 75 | 95.3 | ND | DAFNDJ010000003.1 | [25] |

| Listeria innocua | FDA1205947- C002-006 | 56 | none | 71 | 89.9 | ND | ABJLEO010000012.1 | UN |

| Listeria innocua | FDA0904545 | 55.5 | none | 71 | 92.9 | 92.9 | ABEKZN010000012.1 | UN |

| Listeria innocua | FM23-157 | 53 | mef(A), msr(D), vat-like | 71 | 95.5 | ND | ABLHUQ010000017.1 | UN |

| Listeria innocua | FNW2205 | 55 | none | 68 | 92.9 | 93 | ABYVVV010000010.1 | UN |

| Listeria innocua | 22-014951-BAC-01 | 53 | none | 71 | 95.6 | 94.7 | ABGJAN010000006.1 | UN |

| Listeria innocua | P222130041-7 | 51 | none | 78 | 94.7 | 94.3 | ABTHAR010000006.1 | UN |

| Listeria innocua | M-42 | 55.5 | mef(A), vat-like, arr, ant(6)-Ia, spw, lnu-like | 68 | 91.8 | 92.2 | DANSOM010000007.1 | [25] |

2.3. Detection of ICEs and Genomic Islands

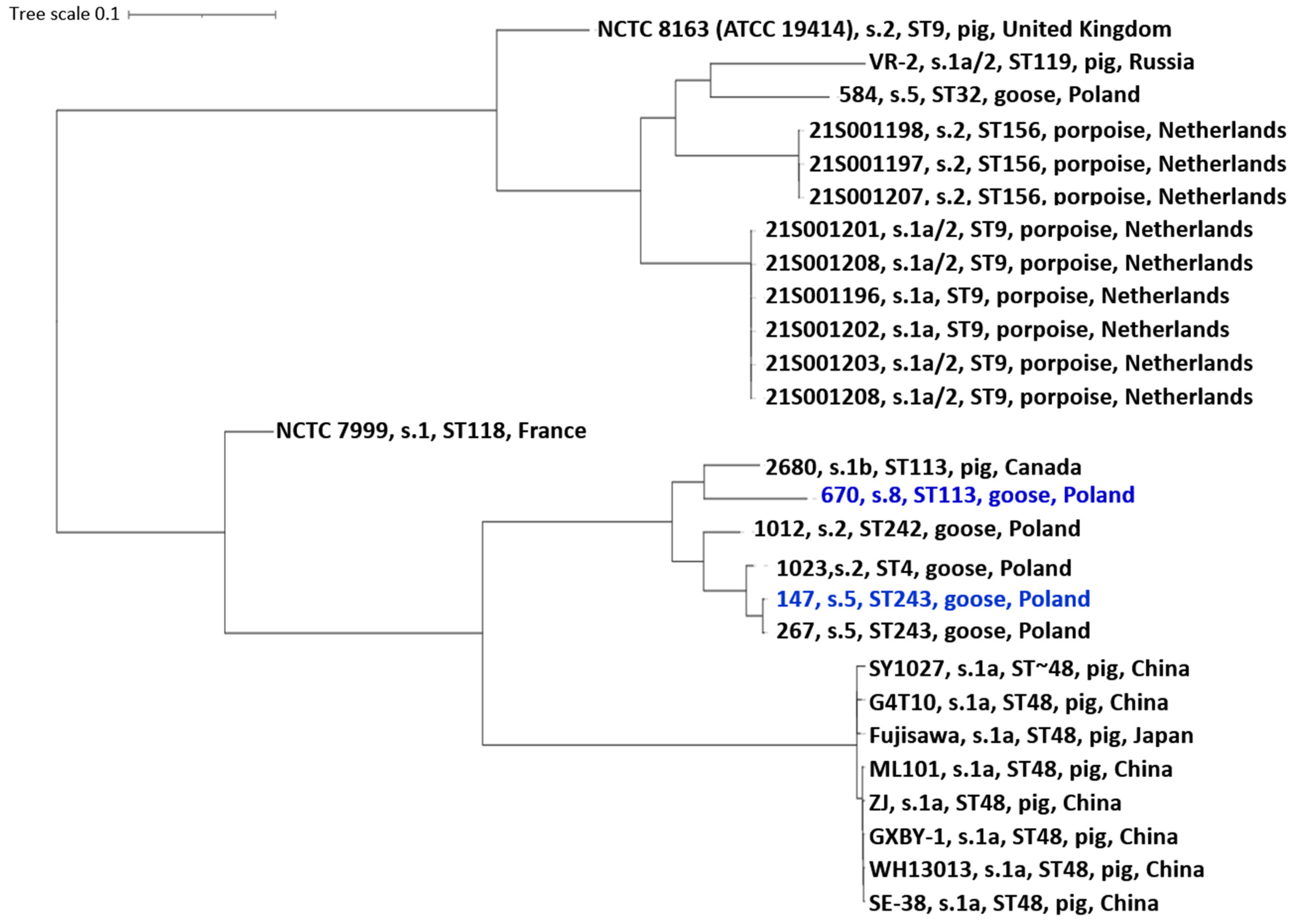

2.4. Core Genome Phylogeny

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Isolation, Identification, and Phenotypic Characterization of E. rhusiopathiae Strains

3.2. Whole Genome Sequencing

3.3. Detection of Resistance Genes, Genomic Islands and Prophage DNA

3.4. Determination of Susceptibility to Streptogramins and Lincosamides

3.5. Detection of lnu(J) Gene

3.6. Determination of Homology Between DNA Sequences

3.7. Multilocus Sequence Typing

3.8. Phylogenetic Inference

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Stackebrandt, E. Erysipelothrix. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria, 1st ed.; Whitman, W.B., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA; Bergey’s Manual Trust: Glasgow, UK, 2015; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, T.; Wódz, K.; Kwiecieński, P.; Kwieciński, A.; Dec, M. Incidence of erysipelas in waterfowl in Poland—Clinical & pathological investigations. Br. Poult. Sci. 2024, 65, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobrek, K.; Nowak, M.; Borkowska, J.; Bobusia, K.; Gaweł, A. An outbreak of erysipelas in commercial geese. Pak. Vet. J. 2016, 36, 372–374. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, F.T.W.; Bisgaard, M. “Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae—Różyca” [Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae—Erysipelas]. In Choroby Drobiu [Poultry Diseases], 1st ed.; Wieliczko, A., Ed.; Edra Urban & Partner: Wrocław, Poland, 2011; pp. 257–261. [Google Scholar]

- Dec, M.; Nowak, T.; Webster, J.; Wódz, K. Serotypes, Antimicrobial Susceptibility, and Potential Mechanisms of Resistance Gene Transfer in Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains from Waterfowl in Poland. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Feng, C.; Jiang, Y.; Ye, C.; Wei, Y.; Liu, J.; Zeng, Z. Mobile genetic elements encoding antibiotic resistance genes and virulence genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae: Important pathways for the acquisition of virulence and resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1529157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Dai, X.; Wu, Z.; Hu, X.; Sun, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Han, P.; Zhao, J.; Liu, G.; et al. Conjugative transfer of streptococcal prophages harboring antibiotic resistance and virulence genes. ISME J. 2023, 17, 1467–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirós, P.; Colomer-Lluch, M.; Martínez-Castillo, A.; Miró, E.; Argente, M.; Jofre, J.; Navarro, F.; Muniesa, M. Antibiotic resistance genes in the bacteriophage DNA fraction of human fecal samples. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 606–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Li, Y.X.; Xu, C.W.; Xie, X.J.; Li, P.; Ma, G.X.; Lei, C.W.; Liu, J.X.; Zhang, A.Y. Genome sequence of multidrug-resistant Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae ZJ carrying several acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 21, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dec, M.; Zomer, A.; Webster, J.; Nowak, T.; Stępień-Pyśniak, D.; Urban-Chmiel, R. Integrative and Conjugative Elements and Prophage DNA as Carriers of Resistance Genes in Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains from Domestic Geese in Poland. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, A.H.; Li, Y.; Jiang, J.; Jiang, P.; Leung, F.C. Complete genome assembly and characterization of an outbreak strain of the causative agent of swine erysipelas—Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae SY1027. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Kang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, J.; Jin, M. The C-Terminal Repeat Units of SpaA Mediate Adhesion of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae to Host Cells and Regulate Its Virulence. Biology 2022, 11, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dec, M.; Łagowski, D.; Nowak, T.; Pietras-Ożga, D.; Herman, K. Serotypes, Antibiotic Susceptibility, Genotypic Virulence Profiles and SpaA Variants of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains Isolated from Pigs in Poland. Pathogens 2023, 12, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei Javan, R.; Ramos-Sevillano, E.; Akter, A.; Brown, J.; Brueggemann, A.B. Prophages and satellite prophages are widespread in Streptococcus and may play a role in pneumococcal pathogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatfull, G.F.; Hendrix, R.W. Bacteriophages and their genomes. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldeguer-Riquelme, B.; Conrad, R.E.; Antón, J.; Rosselló-Móra, R.; Konstantinidis, K.T. A Natural ANI Gap That Can Define Intra-Species Units of Bacteriophages and Other Viruses. mBio 2024, 15, e01536-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Bowring, B.; Stroud, L.; Marsh, I.; Sales, N.; Bogema, D. Population Structure and Genomic Characteristics of Australian Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Reveals Unobserved Diversity in the Australian Pig Industry. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Shiraiwa, K.; Ogura, Y.; Ooka, T.; Nishikawa, S.; Eguchi, M.; Hayashi, T.; Shimoji, Y. Clonal Lineages of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Responsible for Acute Swine Erysipelas in Japan Identified by Using Genome-Wide Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism Analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00130-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, R.; Formenti, N.; Caló, S.; Chiari, M.; Zoric, M.; Alborali, G.L.; Sørensen Dalgaard, T.; Wattrang, E.; Eriksson, H. Comparative genome analysis of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae isolated from domestic pigs and wild boars suggests host adaptation and selective pressure from the use of antibiotics. Microb. Genom. 2020, 6, mgen000412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, T.L.; Kollanandi Ratheesh, N.; Harvey, W.T.; Thomson, J.R.; Williamson, S.; Biek, R.; Opriessnig, T. Genomic and Immunogenic Protein Diversity of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Isolated From Pigs in Great Britain: Implications for Vaccine Protection. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Rhee, M.S.; Chang, D.H.; Kim, B.C. Whole-genome sequence of Erysipelothrix larvae LV19(T) (=KCTC 33523(T)), a useful strain for arsenic detoxification, from the larval gut of the rhinoceros beetle, Trypoxylus dichotomus. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 223, 40–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Wu, C.-H.; Shih, C.-J.; Wu, Y.-C.; Lai, S.-J.; You, Y.-T.; Chen, S.-C. Complete genome sequence of Anaerotignum sp. strain MB30-C6, isolated from sewage sludge of the wastewater treatment plant at a steel factory. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2024, 13, e0007824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaiz, M.; Poehlein, A.; Wilhelm, W.; Mook, A.; Daniel, R.; Dürre, P.; Bengelsdorf, F.R. Refining and illuminating acetogenic Eubacterium strains for reclassification and metabolic engineering. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggel, M.; Cernela, N.; Horlbog, J.A.; Stephan, R. Oxford Nanopore’s 2024 sequencing technology for Listeria monocytogenes outbreak detection and source attribution: Progress and clone-specific challenges. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, e0108324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souvorov, A.; Agarwala, R.; Lipman, D.J. SKESA: Strategic k-mer extension for scrupulous assemblies. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colavecchio, A.; Cadieux, B.; Lo, A.; Goodridge, L.D. Bacteriophages Contribute to the Spread of Antibiotic Resistance Genes among Foodborne Pathogens of the Enterobacteriaceae Family—A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclerc, Q.J.; Wildfire, J.; Gupta, A.; Lindsay, J.A.; Knight, G.M. Growth-Dependent Predation and Generalized Transduction of Antimicrobial Resistance by Bacteriophage. mSystems 2022, 7, e0013522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbel, D.; Càmara, J.; García, E.; Tubau, F.; Guérin, F.; Giard, J.C.; Domínguez, M.Á.; Cattoir, V.; Ardanuy, C. A novel genomic island harbouring lsa(E) and lnu(B) genes and a defective prophage in a Streptococcus pyogenes isolate resistant to lincosamide, streptogramin A and pleuromutilin antibiotics. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 54, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, A. Predicting phage-host specificity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habann, M.; Leiman, P.G.; Vandersteegen, K.; Van den Bossche, A.; Lavigne, R.; Shneider, M.M.; Bielmann, R.; Eugster, M.R.; Loessner, M.J.; Klumpp, J. Listeria phage A511, a model for the contractile tail machineries of SPO1-related bacteriophages. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 92, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, S.; Coffey, A.; Edwards, R.; Meaney, W.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Ross, R.P. Genome of staphylococcal phage K: A new lineage of Myoviridae infecting gram-positive bacteria with a low G+C content. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 2862–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göller, P.C.; Elsener, T.; Lorgé, D.; Radulovic, N.; Bernardi, V.; Naumann, A.; Amri, N.; Khatchatourova, E.; Coutinho, F.H.; Loessner, M.J.; et al. Multi-species host range of staphylococcal phages isolated from wastewater. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanetti, E.; Brenciani, A.; Morroni, G.; Tiberi, E.; Pasquaroli, S.; Mingoia, M.; Varaldo, P.E. Transduction of the Streptococcus pyogenes bacteriophage Φm46.1, carrying resistance genes mef(A) and tet(O), to other Streptococcus species. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, P.; Abedon, S.T. Bacteriophage host range and bacterial resistance. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 70, 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrie, S.J.; Samson, J.E.; Moineau, S. Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flannagan, S.E.; Zitzow, L.A.; Su, Y.A.; Clewell, D.B. Nucleotide sequence of the 18-kb conjugative transposon Tn916 from Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid 1994, 32, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, H.P.; Anvar, S.Y.; Frank, J.; Lawley, T.D.; Roberts, A.P.; Smits, W.K. Complete genome sequence of BS49 and draft genome sequence of BS34A, Bacillus subtilis strains carrying Tn916. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 362, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Hu, Y.; Wu, H.; Feng, Z.; Hu, C.; Hu, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, W.; Yu, X. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of a Highly Virulent Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strain. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2024, 2024, 5401707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.P. Integration sites for genetic elements in prokaryotic tRNA and tmRNA genes: Sublocation preference of integrase subfamilies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirova, M.E.; Roumiantseva, M.L.; Saksaganskaia, A.S.; Muntyan, V.S.; Gaponov, S.P.; Mengoni, A. Hot Spots of Site-Specific Integration into the Sinorhizobium meliloti Chromosome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellanger, X.; Payot, S.; Leblond-Bourget, N.; Guédon, G. Conjugative and mobilizable genomic islands in bacteria: Evolution and diversity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 720–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petinaki, E.; Guérin-Faublée, V.; Pichereau, V.; Villers, C.; Achard, A.; Malbruny, B.; Leclercq, R. Lincomycin resistance gene lnu(D) in Streptococcus uberis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grindley, N.D.; Whiteson, K.L.; Rice, P.A. Mechanisms of site-specific recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006, 75, 567–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, M.; Yuan, J.; Lin, Y.; Pevzner, P.A. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.T.; Liu, P.Y.; Shih, P.W. Homopolish: A method for the removal of systematic errors in nanopore sequencing by homologous polishing. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; O’Neill, K.R.; Haft, D.H.; DiCuccio, M.; Chetvernin, V.; Badretdin, A.; Coulouris, G.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Durkin, A.S.; et al. RefSeq: Expanding the Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline reach with protein family model curation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1020–D1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolaia, V.; Kaas, R.S.; Ruppe, E.; Roberts, M.C.; Schwarz, S.; Cattoir, V.; Philippon, A.; Allesoe, R.L.; Rebelo, A.R.; Florensa, A.F.; et al. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3491–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Raphenya, A.R.; Lau, T.T.Y.; Tsang, K.K.; Bouchard, M.; Edalatmand, A.; Huynh, W.; Nguyen, A.V.; Cheng, A.A.; Liu, S.; et al. CARD 2020: Antibiotic resistome surveillance with the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D517–D525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, D.; Grant, J.R.; Marcu, A.; Sajed, T.; Pon, A.; Liang, Y.; Wishart, D.S. PHASTER: A better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W16–W21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyres, K.L.; Wick, R.R.; Gorrie, C.; Jenney, A.; Follador, R.; Thomson, N.R.; Holt, K.E. Identification of Klebsiella capsule synthesis loci from whole genome data. Microb. Genom. 2016, 2, e000102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, C.L.M.; Chooi, Y.H. Clinker & clustermap.js: Automatic generation of gene cluster comparison figures. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2473–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.H.; Ha, S.M.; Lim, J.M.; Kwon, S.J.; Chun, J. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2017, 110, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kille, B.; Nute, M.G.; Huang, V.; Kim, E.; Phillippy, A.M.; Treangen, T.J. Parsnp 2.0: Scalable Core-Genome Alignment for Massive Microbial Datasets. bioRxiv 2024, 2024.01.30.577458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJsseldijk, L.L.; Begeman, L.; Duim, B.; Gröne, A.; Kik, M.J.L.; Klijnstra, M.D.; Lakemeyer, J.; Leopold, M.F.; Munnink, B.B.O.; Ten Doeschate, M.; et al. Harbor porpoise deaths associated with Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, the Netherlands, 2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seru, L.V.; Forde, T.L.; Roberto-Charron, A.; Mavrot, F.; Niu, Y.D.; Kutz, S.J. Genomic characterization and virulence gene profiling of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae isolated from widespread muskox mortalities in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.B.; Xie, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, F.; Wu, J. Complete genome sequence of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae strain GXBY-1 isolated from acute swine erysipelas outbreaks in south China. Genom. Data 2016, 8, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Lv, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, T.; Kang, C.; Yang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Characterization of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae isolates from diseased pigs in 15 Chinese provinces from 2012 to 2018. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Ooka, T.; Shi, F.; Ogura, Y.; Nakayama, K.; Hayashi, T.; Shimoji, Y. The genome of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, the causative agent of swine erysipelas, reveals new insights into the evolution of Firmicutes and intracellular adaptations. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 2959–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Peng, Z.; Ding, Y.; Jie, K.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; et al. Comparative genome analysis of a pathogenic Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae isolate WH13013 from pig reveals potential genes involved in bacterial adaptations and pathogenesis. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Park, S.Y.; Seo, H.W.; Cho, Y.; Choi, S.G.; Seo, S.; Han, W.; Lee, N.K.; Kwon, H.; Han, J.E.; et al. Pathological and genomic findings of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae isolated from a free-ranging rough-toothed dolphin (Steno bredanensis) stranded in Korea. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 774836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovalchuk, S.; Babii, A. Draft genome sequence data of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae vaccine strain VR-2. Data Brief 2020, 33, 106352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesbitt, K.; Bloodgood, J.; Mullis, M.M.; Deming, A.C.; Colegrove, K.; Reese, B.K. Draft genome sequences of Erysipelothrix sp. strains isolated from stranded septic bottlenose dolphins in Alabama, USA. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2022, 11, e0027322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zautner, A.E.; Tersteegen, A.; Schiffner, C.J.; Ðilas, M.; Marquardt, P.; Riediger, M.; Delker, A.M.; Mäde, D.; Kaasch, A.J. Human Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae infection via bath water—Case report and genome announcement. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 981477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileto, I.; Merla, C.; Corbella, M.; Gaiarsa, S.; Kuka, A.; Ghilotti, S.; De Cata, P.; Baldanti, F.; Cambieri, P. Bloodstream infection caused by Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae in an immunocompetent patient. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.K.; Miller, M.A.; Tekedar, H.C.; Rose, D.; García, J.C.; LaFrentz, B.R.; Older, C.E.; Waldbieser, G.C.; Pomaranski, E.; Shahin, K.; et al. Pathology, microbiology, and genetic diversity associated with Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae and novel Erysipelothrix spp. infections in southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis). Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1303235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraiwa, K.; Ogawa, Y.; Nishikawa, S.; Eguchi, M.; Shimoji, Y. Multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection and differentiation of clonal lineages of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae serovar 1a strains circulating in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2017, 79, 1318–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, N.; Burek Huntington, K.; Goertz, C.E.C.; Hunter, N.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Forde, T. Erysipelothrix in Cook Inlet, Alaska, USA: An emerging bacterial pathogen of the endangered Cook Inlet beluga whale. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2025, 163, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Medvecky, M.; Tornos, J.; Clessin, A.; Le Net, R.; Gantelet, H.; Gamble, A.; Forde, T.L.; Boulinier, T. Erysipelothrix amsterdamensis sp. nov., associated with mortalities among endangered seabirds. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 006264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isolate ID (Genome ID) | 670 (24S01951-1) | 147 (24S1949-1) |

|---|---|---|

| GenBank Acc. No. | CP183044.1 | CP184721.1 |

| Serotype | 8 | 5 |

| Source/host | Domestic goose | Domestic goose |

| Year of isolation, country | 2020, Poland | 2020, Poland |

| Genome size (bp) | 1,874,230 bp | 1,918,116 bp |

| Genes (total) | 1842 | 1871 |

| Genes (coding) | 1753 | 1795 |

| tRNAs | 55 | 55 |

| rRNAs | 7, 7, 7 (5S, 16S, 23S) | 3, 3, 3 (5S, 16S, 23S) |

| GC content (%) | 36.6 | 36.3 |

| ST (MLST) | 113 | 243 |

| Antimicrobial susceptibility test results (MIC in μg/mL) a | TET(32), LIN(>64), CLI(2), TIA(>64), ERY(0.125), ENR(8), AMP(≤0.06) QDA(0.5), STR(128), SPE(64) | TET(32), LIN(8) b, CLI(0.125), TIA(0.5), ERY(0.125), ENR(8), AMP(≤0.06) QDA(0.38), STR(>512), SPE(512) |

| Resistance genes | tetM, lnuB, lsaE | tetM, ant(6)-Ia, spw, lnu(J) c, vat-family c |

| Mutations in gyrA gene & in parC gene | Thr86 → Ile Ser81 → Ile | Thr86 → Lys Ser81 → Ile |

| MGEs |

|

|

| Strain | GenBank Acc. No. | Resistance Genes | MIC [µg/mL] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lincomycin R ≥ 16 µg/mL I 4–8 µg/mL | Clindamycin R ≥ 1 µg/mL I 0.5 µg/mL | Quinupristin/Dalfopristin | |||

| ATCC 19414 | LR134439.1 | none | 0.25–0.5 | 0.15–0.03 | 0.38 |

| 147 | CP184721.1 | tetM, ant(6)-Ia, spw, lnu(J) *, vat-family * | 8 | 0.06–0.125 | 0.38 |

| 136 | NA | tetM, ant(6)-Ia, spw, lnu(J) *, vat-family * | 4–8 | 0.125–0.25 | 0.5 |

| 670 | CP183044.1 | tetM, lnuB, lsaE | >64 | 2 | 0.5 |

| 1023 | CP180440.1 | tetM, lnuB, lsaE, ant(6)-Ia, spw, erm47 | >64 | 2 | 0.5 |

| 584 | CP192437.1 | none | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.38 |

| 1012 | CP180318.1 | tetM | 0.5–1 | 0.06–0.125 | 0.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dec, M.; Zomer, A.L.; Broekhuizen-Stins, M.J.; Urban-Chmiel, R. Prophage φEr670 and Genomic Island GI_Er147 as Carriers of Resistance Genes in Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010250

Dec M, Zomer AL, Broekhuizen-Stins MJ, Urban-Chmiel R. Prophage φEr670 and Genomic Island GI_Er147 as Carriers of Resistance Genes in Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010250

Chicago/Turabian StyleDec, Marta, Aldert L. Zomer, Marian J. Broekhuizen-Stins, and Renata Urban-Chmiel. 2026. "Prophage φEr670 and Genomic Island GI_Er147 as Carriers of Resistance Genes in Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010250

APA StyleDec, M., Zomer, A. L., Broekhuizen-Stins, M. J., & Urban-Chmiel, R. (2026). Prophage φEr670 and Genomic Island GI_Er147 as Carriers of Resistance Genes in Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010250