A Longitudinal 3D Live-Cell Imaging Platform to Uncover AAV Vector–Host Dynamics at Single-Cell Resolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

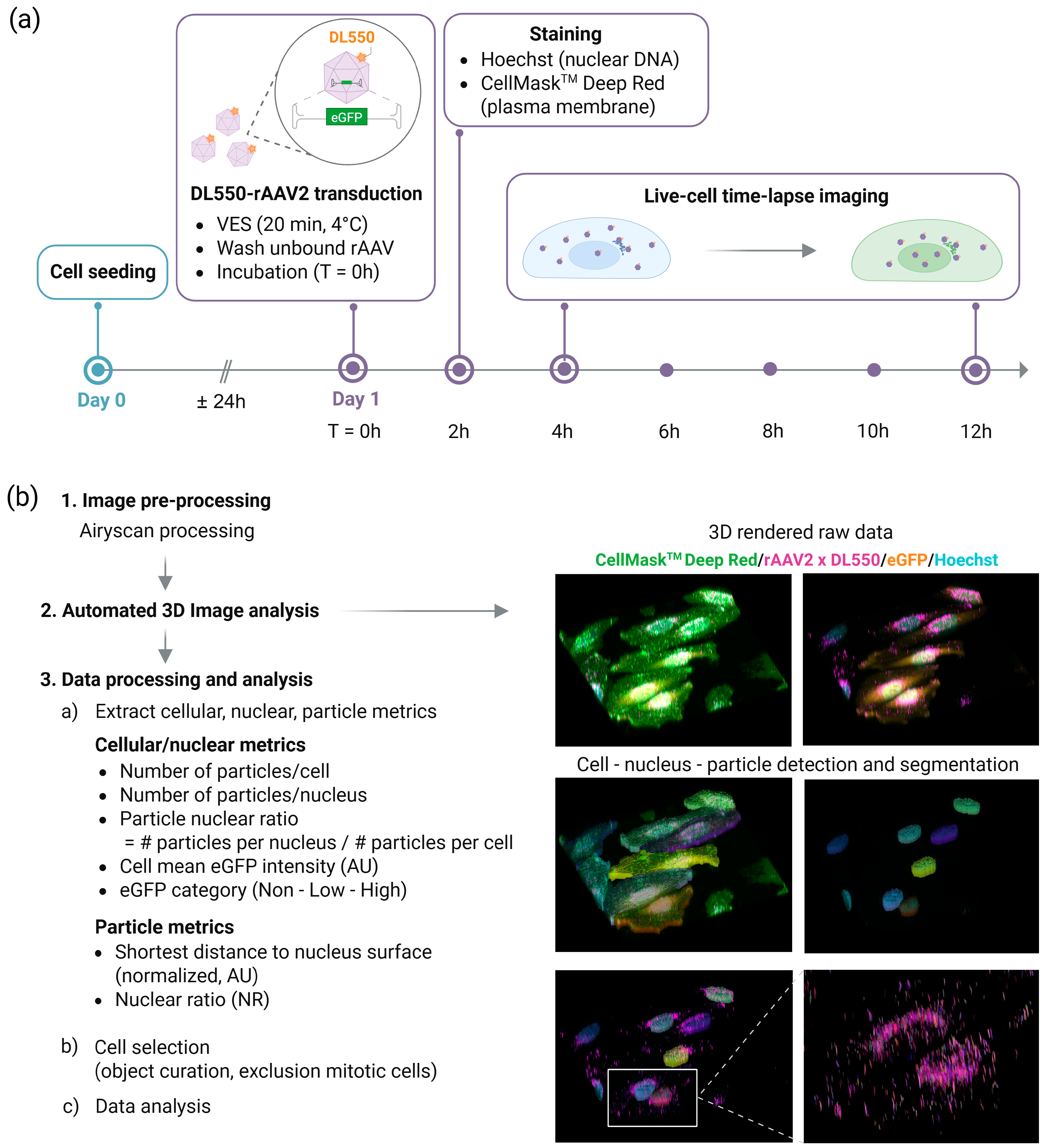

2.1. Real-Time Live-Cell Imaging Workflow

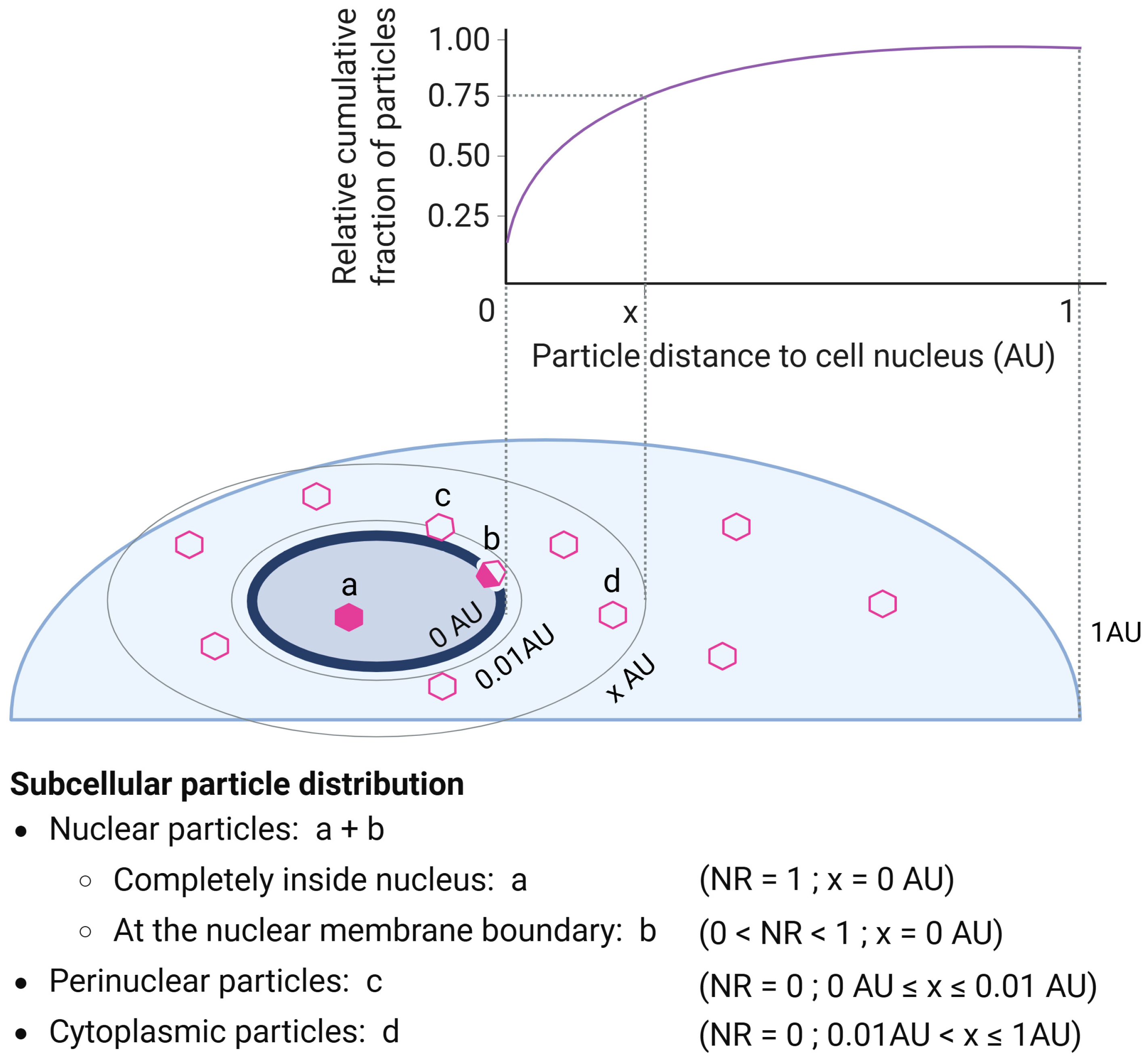

2.2. Three-Dimensional Image Analysis Pipeline

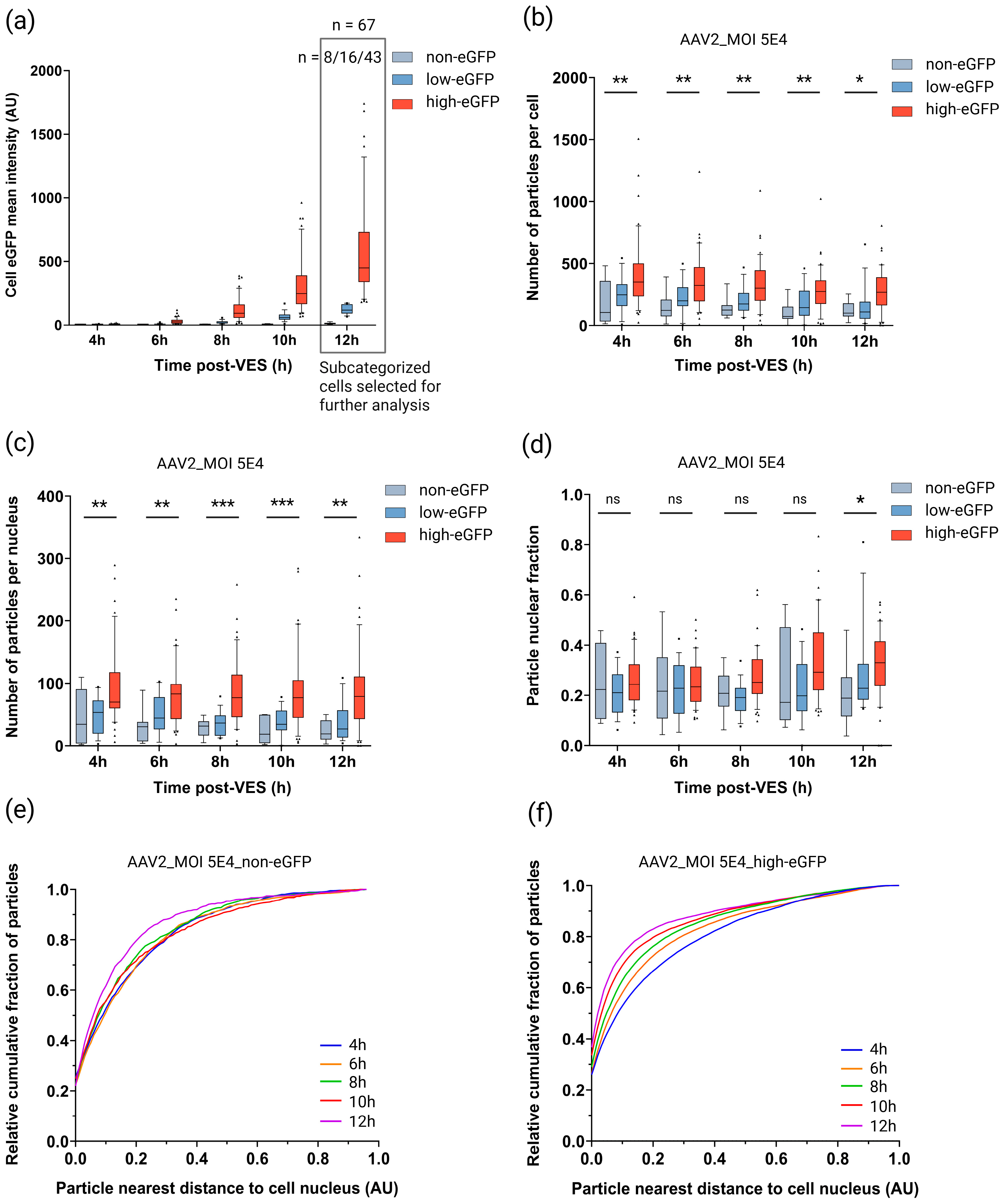

2.3. Subcellular Dynamics of rAAV in Cells Exhibiting High Transgene Expression

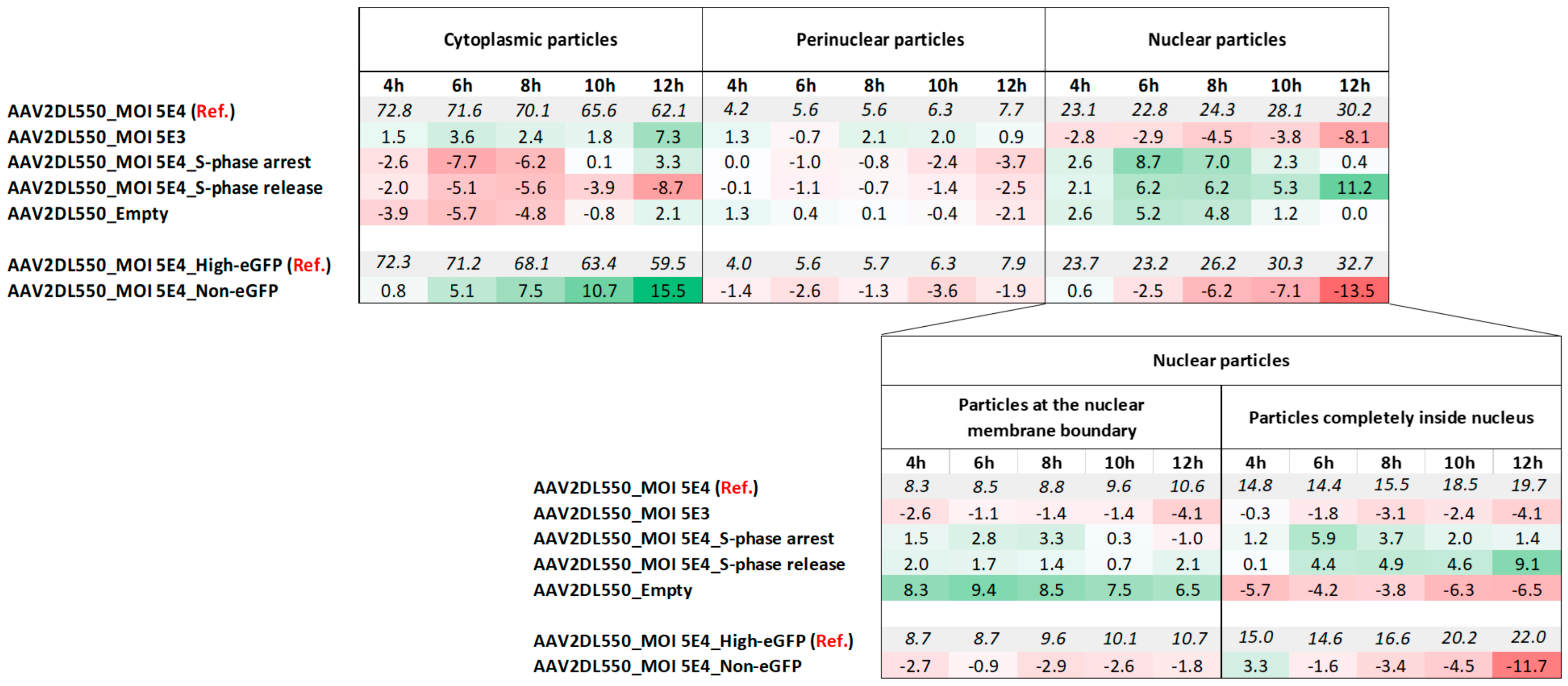

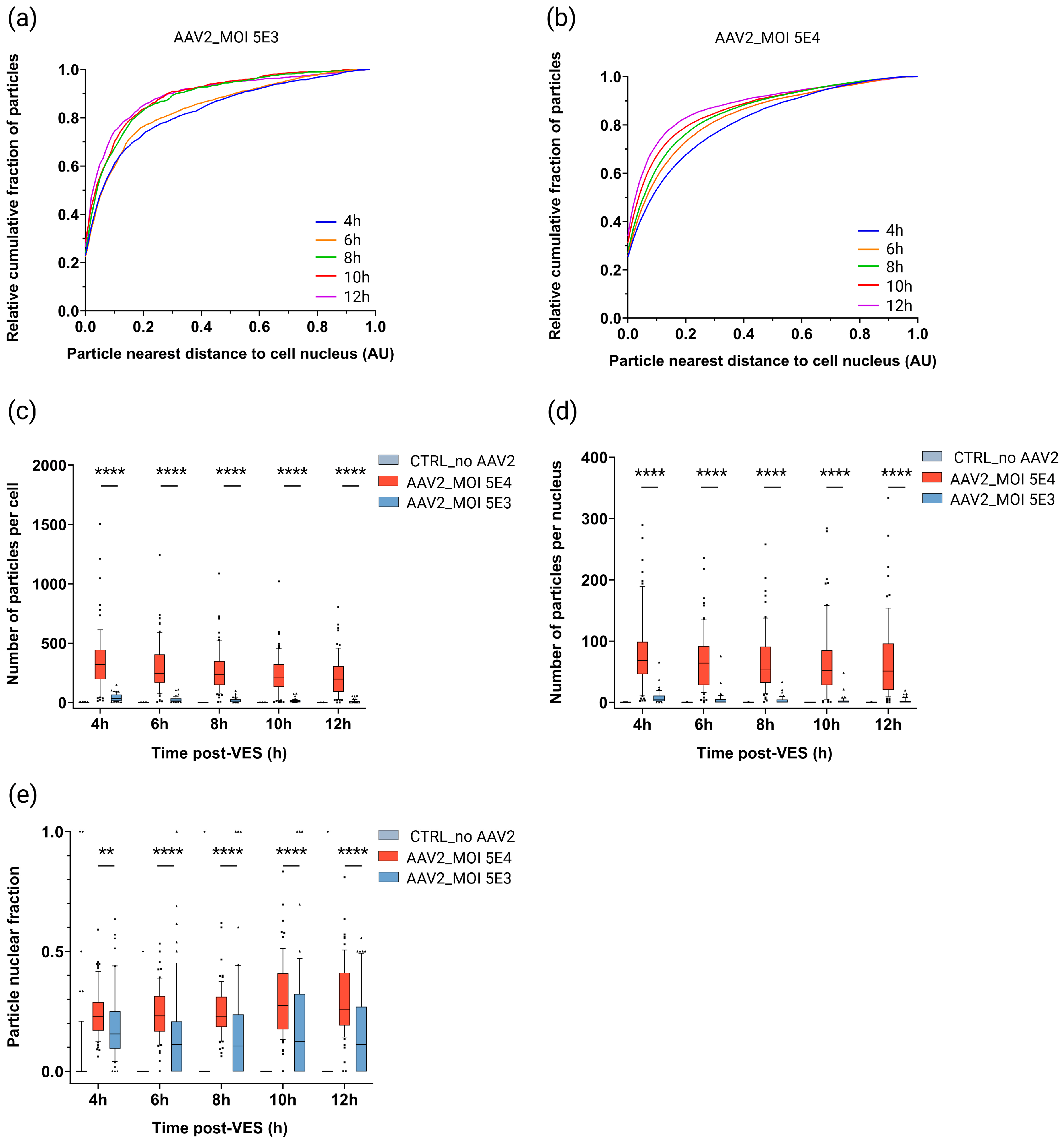

2.4. Cytoplasmic Trafficking Efficiency and Nuclear Accumulation Are Dose-Dependent

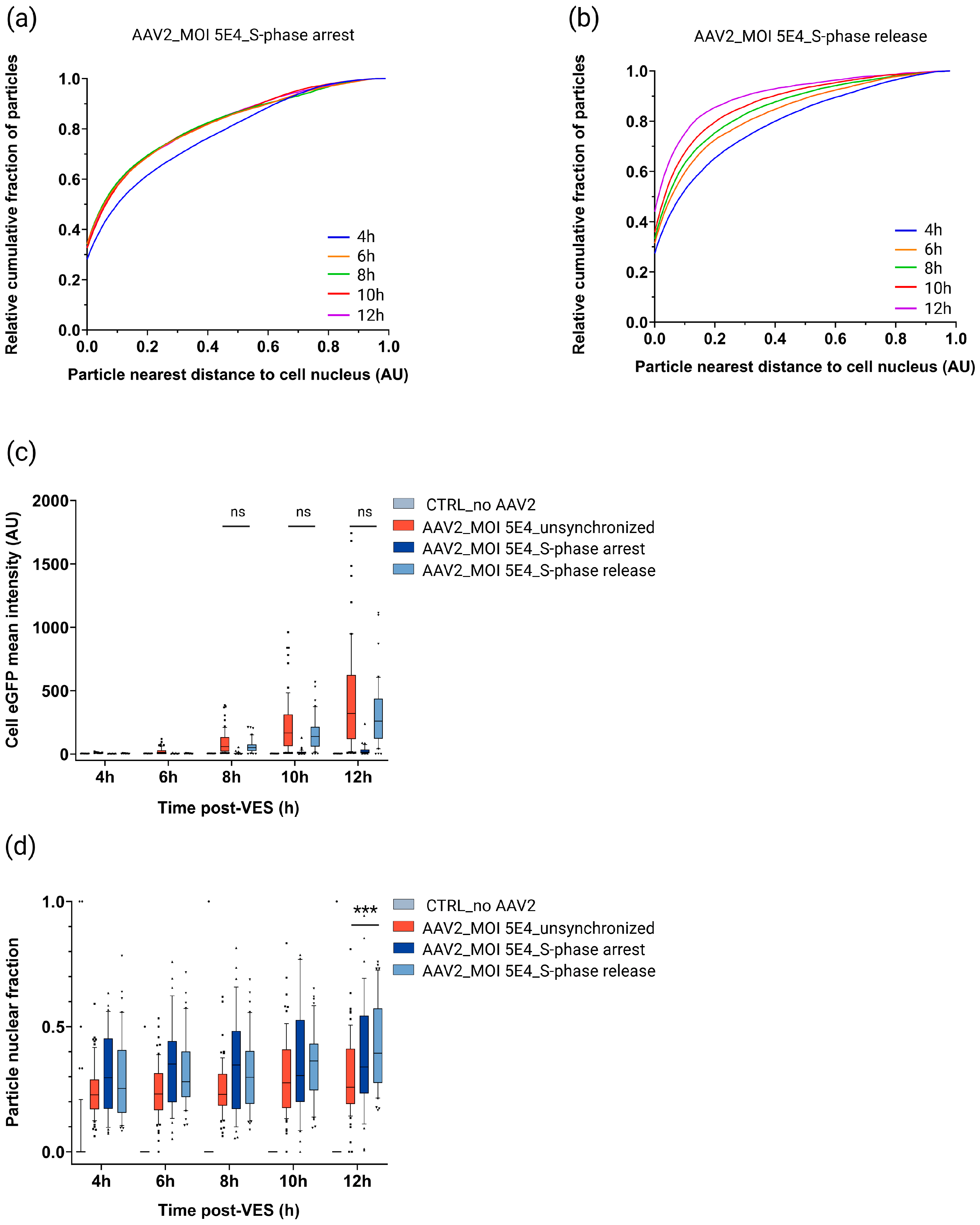

2.5. S-Phase Cell Cycle Arrest and Release

2.5.1. Cell Cycle Progression Is Needed for Efficient rAAV2 Cytoplasmic Trafficking Toward the Nucleus and (High) Transgene Expression

2.5.2. rAAV Nuclear Import Is Facilitated in S and G2 Cell Cycle Phases

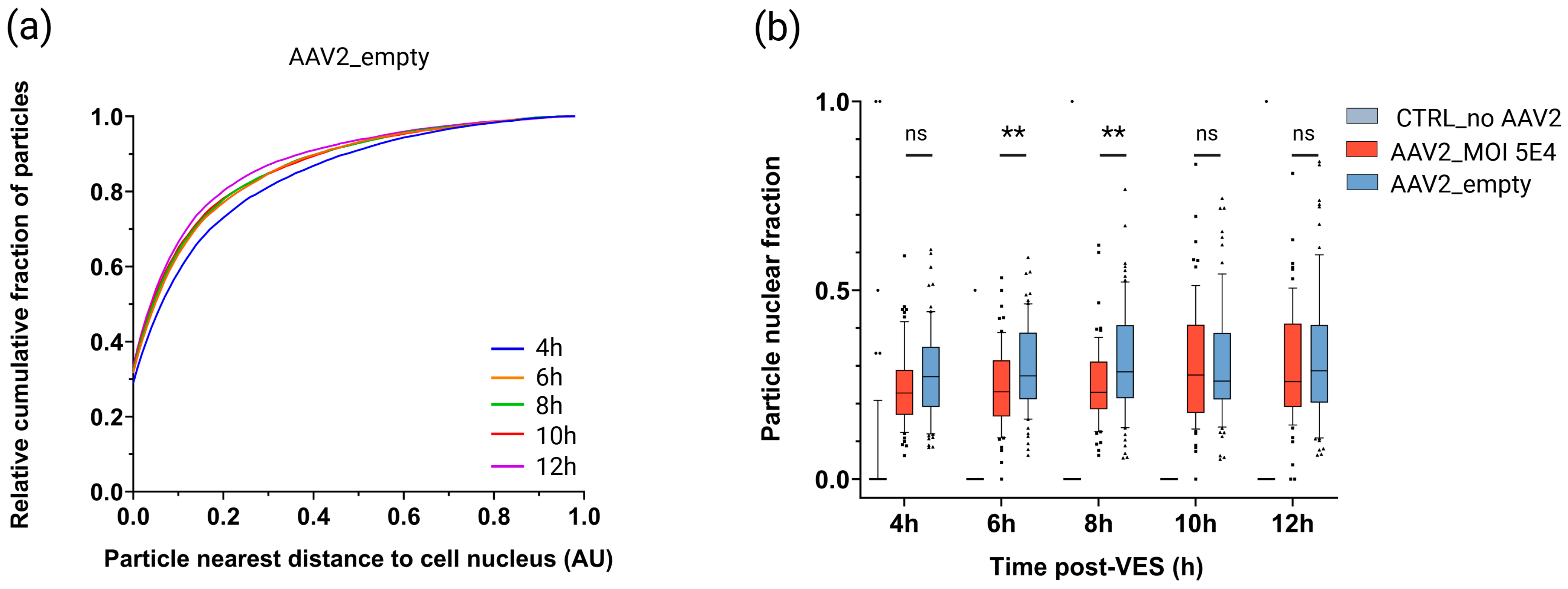

2.6. Empty Vectors Show Distinct Cytoplasmic Trafficking and Impaired Nuclear Accumulation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Production and Purification of rAAV

4.2.1. Transgene-Containing rAAV

4.2.2. Empty rAAV

4.3. Fluorescent DyLightTM550 Labeling of rAAV

4.4. Time-Lapse Fluorescent Live-Cell Confocal Imaging

4.4.1. Sample Preparation

4.4.2. Confocal Image Acquisition

4.5. Three-Dimensional Image Analysis

4.5.1. Cell Segmentation and Tracking

4.5.2. Viral Particle Detection

4.5.3. Cell, Particle, and Nucleus Measurements

4.5.4. Data Processing and Analysis

4.6. HeLa S-Phase Cell Cycle Arrest and Release

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| rAAV | Recombinant adeno-associated virus |

| Rep | Replication |

| Cap | Capsid |

| TGN | Trans-Golgi network |

| VP1u | Viral protein 1 unique region |

| MOI | Multiplicity of infection |

| NPC | Nuclear pore complex |

| NEBD | Nuclear envelope breakdown |

| Wt | Wild-type |

| eGFP | Enhanced green fluorescent protein |

| DL | DyLightTM |

| VES | Vector entry synchronization |

| ROI | Region of interest |

| NR | Nuclear ratio |

| AU | Arbitrary unit |

| ExM | Expansion microscopy |

| STED | Stimulation emission depletion |

| MTOC | Microtubule-organizing center |

| DPBS | Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| ddPCR | Droplet digital polymerase chain reaction |

References

- Hoggan, M.; Blacklow, N.; Rowe, W. Studies of Small Dna Viruses Found in Various Adenovirus Preparations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1966, 55, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayor, H.D.; Jamison, R.M.; Jordan, L.E.; Melnick, J.L. Structure and Composition of a Small Particle Prepared from a Simian Adenovirus. J. Bacteriol. 1965, 90, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, J.A.; Maizel, J.V.; Inman, J.K.; Shatkin, A.J. Structural Proteins of Adenovirus-Associated Viruses. J. Virol. 1971, 8, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Lusby, E.W.; Berns, K.I. Nucleotide Sequence and Organization of the Adeno-Associated Virus 2 Genome. J. Virol. 1983, 45, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijder, J.; van de Waterbeemd, M.; Damoc, E.; Denisov, E.; Grinfeld, D.; Bennett, A.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Makarov, A.; Heck, A.J.R. Defining the Stoichiometry and Cargo Load of Viral and Bacterial Nanoparticles by Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7295–7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-H.; Gessler, D.J.; Zhan, W.; Gallagher, T.L.; Gao, G. Adeno-Associated Virus as a Delivery Vector for Gene Therapy of Human Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Peng, H.; Ma, Y.; Yuan, H.; Jiang, H. In Vivo Applications and Toxicities of AAV-Based Gene Therapies in Rare Diseases. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D. Lethal Immunotoxicity in High-Dose Systemic AAV Therapy. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 3123–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, J.S.; Davidson, B.L.; George, L.A.; Byrne, B.J.; Barrett, D. The Future of Gene Therapy: Safer Vectors, Sharper Focus: High-Profile Failures Demand Deep Root Cause Analysis—But the Transformative Potential of AAV Remains within Reach If the Field Is Willing to Learn and Evolve. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 4694–4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Verdera, H.; Kuranda, K.; Mingozzi, F. AAV Vector Immunogenicity in Humans: A Long Journey to Successful Gene Transfer. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 723–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhungel, B.P.; Bailey, C.G.; Rasko, J.E.J. Journey to the Center of the Cell: Tracing the Path of AAV Transduction. Trends Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelich, J.M.; Ma, J.; Dong, B.; Wang, Q.; Chin, M.; Magura, C.M.; Xiao, W.; Yang, W. Super-Resolution Imaging of Nuclear Import of Adeno-Associated Virus in Live Cells. Mol. Ther.-Methods Clin. Dev. 2015, 2, 15047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonnenmacher, M.; Weber, T. Intracellular Transport of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors. Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudek, A.M.; Zabaleta, N.; Zinn, E.; Pillay, S.; Zengel, J.; Porter, C.; Franceschini, J.S.; Estelien, R.; Carette, J.E.; Zhou, G.L.; et al. GPR108 Is a Highly Conserved AAV Entry Factor. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, S.; Carette, J.E. Host Determinants of Adeno-Associated Viral Vector Entry. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2017, 24, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnenmacher, M.; Weber, T. Adeno-Associated Virus 2 Infection Requires Endocytosis through the CLIC/GEEC Patway. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, X.; Yao, T.; Tian, Z.; Zhou, D. Precision Fluorescent Labeling of an Adeno-Associated Virus Vector to Monitor the Viral Infection Pathway. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, e1700374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Zhang, L.N.; Yeaman, C.; Engelhardt, J.F. RAAV2 Traffics through Both the Late and the Recycling Endosomes in a Dose-Dependent Fashion. Mol. Ther. 2006, 13, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelkar, S.; De, B.P.; Gao, G.; Wilson, J.M.; Crystal, R.G.; Leopold, P.L. A Common Mechanism for Cytoplasmic Dynein-Dependent Microtubule Binding Shared among Adeno-Associated Virus and Adenovirus Serotypes. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 7781–7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suikkanen, S.; Aaltonen, T.; Nevalainen, M.; Välilehto, O.; Lindholm, L.; Vuento, M.; Vihinen-Ranta, M. Exploitation of Microtubule Cytoskeleton and Dynein during Parvoviral Traffic toward the Nucleus. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 10270–10279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirosue, S.; Senn, K.; Clément, N.; Nonnenmacher, M.; Gigout, L.; Linden, R.M.; Weber, T. Effect of Inhibition of Dynein Function and Microtubule-Altering Drugs on AAV2 Transduction. Virology 2007, 367, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, K.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, L.; Gu, Z.; Tai, A.; Lee, C.; Tang, Y. Enhanced Real-Time Monitoring of Adeno-Associated Virus Trafficking by Virus-Quantum Dot Conjugates. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 3523–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonnenmacher, M.E.; Cintrat, J.-C.; Gillet, D.; Weber, T. Syntaxin 5-Dependent Retrograde Transport to the Trans -Golgi Network Is Required for Adeno-Associated Virus Transduction. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 1673–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanes-creus, M.; Liao, S.H.Y.; Rojas, A.L.; Kelich, J.; Coyne, J.; Knight, M.; Nazareth, D.; Roca-pinilla, R.; Senapati, S.; Walsh, M.C.; et al. AAV2 Bypasses Direct Endosomal Escape by Using AAVR to Access the Trans-Golgi Network En Route to the Nucleus. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girod, A.; Wobus, C.E.; Zádori, Z.; Ried, M.; Leike, K.; Tijssen, P.; Kleinschmidt, J.A.; Hallek, M. The VP1 Capsid Protein of Adeno-Associated Virus Type 2 Is Carrying a Phospholipase A2 Domain Required for Virus Infectivity. J. Gen. Virol. 2002, 83, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, J.J.; Lakshmanan, R.; Chmely, W.M.; Hull, J.A.; Yu, J.C.; Bennett, A.; McKenna, R.; Agbandje-McKenna, M. Adeno-Associated Virus VP1u Exhibits Protease Activity. Viruses 2019, 11, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieger, J.C.; Snowdy, S.; Samulski, R.J. Separate Basic Region Motifs within the Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid Proteins Are Essential for Infectivity and Assembly. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5199–5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, S.C.; Samulski, R.J. Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Utilizes Host Cell Nuclear Import Machinery To Enter the Nucleus. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4132–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porwal, M.; Cohen, S.; Snoussi, K.; Popa-Wagner, R.; Anderson, F.; Dugot-Senant, N.; Wodrich, H.; Dinsart, C.; Kleinschmidt, J.A.; Panté, N.; et al. Parvoviruses Cause Nuclear Envelope Breakdown by Activating Key Enzymes of Mitosis. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Behzad, A.R.; Carroll, J.B.; Panté, N. Parvoviral Nuclear Import: Bypassing the Host Nuclear-Transport Machinery. J. Gen. Virol. 2006, 87, 3209–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Marr, A.K.; Garcin, P.; Panté, N. Nuclear Envelope Disruption Involving Host Caspases Plays a Role in the Parvovirus Replication Cycle. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 4863–4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seisenberger, G.; Ried, M.U.; Endreß, T.; Büning, H.; Hallek, M.; Bräuchle, C. Real-Time Single-Molecule Imaging of the Infection Pathway of an Adeno-Associated Virus. Science. 2001, 294, 1929–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Warrington, K.H.; Hearing, P.; Hughes, J.; Muzyczka, N. Adenovirus-Facilitated Nuclear Translocation of Adeno-Associated Virus Type 2. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 11505–11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lux, K.; Goerlitz, N.; Schlemminger, S.; Perabo, L.; Goldnau, D.; Endell, J.; Leike, K.; Kofler, D.M.; Finke, S.; Hallek, M.; et al. Green Fluorescent Protein-Tagged Adeno-Associated Virus Particles Allow the Study of Cytosolic and Nuclear Trafficking. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 11776–11787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.-J.; Samulski, R.J. Cytoplasmic Trafficking, Endosomal Escape, and Perinuclear Accumulation of Adeno-Associated Virus Type 2 Particles Are Facilitated by Microtubule Network. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 10462–10473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, F.; Bleker, S.; Leuchs, B.; Fischer, R.; Kleinschmidt, J.A. Adeno-Associated Virus Type 2 Capsids with Externalized VP1/VP2 Trafficking Domains Are Generated Prior to Passage through the Cytoplasm and Are Maintained until Uncoating Occurs in the Nucleus. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 11040–11054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.S.; Wilcher, R. Infectious Entry Pathway of Adeno-Associated Virus and Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 2777–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.-J.; Li, C.; Neumann, A.; Samulski, R.J. Quantitative 3D Tracing of Gene-Delivery Viral Vectors in Human Cells and Animal Tissues. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.S.; Samulski, R.J. Enhancement of Adeno-Associated Virus Infection by Mobilizing Capsids into and Out of the Nucleolus. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 2632–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, S.O.; Lkharrazi, A.; Schraner, E.M.; Michaelsen, K.; Meier, A.F.; Marx, J.; Vogt, B.; Büning, H.; Fraefel, C. Adeno-Associated Virus Type 2 (AAV2) Uncoating Is a Stepwise Process and Is Linked to Structural Reorganization of the Nucleolus. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Sanyal, S.; Bruzzone, R. Breaking Bad: How Viruses Subvert the Cell Cycle. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthet, C.; Raj, K.; Saudan, P.; Beard, P. How Adeno-Associated Virus Rep78 Protein Arrests Cells Completely in S Phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 13634–13639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saudan, P. Inhibition of S-Phase Progression by Adeno-Associated Virus Rep78 Protein Is Mediated by Hypophosphorylated PRb. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 4351–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, K.; Chen, W.; McDonald, W.F.; Zhou, X.; Muzyczka, N. Purification of Host Cell Enzymes Involved in Adeno-Associated Virus DNA Replication. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 5777–5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.W.; Miller, A.D.; Alexander, I.E. Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors Preferentially Transduce Cells in S Phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 8915–8919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, I.E.; Russell, D.W.; Miller, A.D. DNA-Damaging Agents Greatly Increase the Transduction of Nondividing Cells by AAV Vectors. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 8282–8287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, P.; Shera, D.; McPhee, S.W.J.; Francis, J.S.; Kolodny, E.H.; Bilaniuk, L.T.; Wang, D.-J.; Assadi, M.; Goldfarb, O.; Goldman, H.W.; et al. Long-Term Follow-Up After Gene Therapy for Canavan Disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 165ra163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, J.R.; Smith, G.A.; Rocha, E.M.; Hayes, M.A.; Beagan, J.A.; Hallett, P.J.; Isacson, O. Widespread Neuron-Specific Transgene Expression in Brain and Spinal Cord Following Synapsin Promoter-Driven AAV9 Neonatal Intracerebroventricular Injection. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 576, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnödt, M.; Büning, H. Improving the Quality of Adeno-Associated Viral Vector Preparations: The Challenge of Product-Related Impurities. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods 2017, 28, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.; Federspiel, J.D.; Rogers, K.; Khatri, A.; Rao-Dayton, S.; Ocana, M.F.; Lim, S.; D’Antona, A.M.; Casinghino, S.; Somanathan, S. Complement Activation by Adeno-Associated Virus-Neutralizing Antibody Complexes. Hum. Gene Ther. 2023, 34, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, H.C.J. Immunogenicity and Toxicity of AAV Gene Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 975803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, J.F.; Lesko, S.L.; Evans, E.L.; Sherer, N.M. Studying Retroviral Life Cycles Using Visible Viruses and Live Cell Imaging. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2024, 11, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golm, S.K.; Hübner, W.; Müller, K.M. Fluorescence Microscopy in Adeno-Associated Virus Research. Viruses 2023, 15, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Yu, C.-C.; Gao, L.; Piatkevich, K.D.; Neve, R.L.; Munro, J.B.; Upadhyayula, S.; Boyden, E.S. A Highly Homogeneous Polymer Composed of Tetrahedron-like Monomers for High-Isotropy Expansion Microscopy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaib, A.H.; Chouaib, A.A.; Chowdhury, R.; Mihaylov, D.; Imani, V.; Georgiev, S.V.; Mougios, N.; Reshetniak, S.; Mimoso, T.; Chen, H.; et al. Visualizing Proteins by Expansion Microscopy. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Meister, R.; Tode, J.; Framme, C.; Fuchs, H. Long-Term in Vitro Monitoring of AAV-Transduction Efficiencies in Real-Time with Hoechst 33342. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-Jaramillo, L.F.; Yue, L.; Fingal, J.; Rydell, G.; Johansson, M.; Edreira, T.; Müller, O.J.; Hille, S.; Müller, M.; Gallardo, F.; et al. Real-Time Genome Imaging of Host Interactions in Adeno-Associated Virus Genome Release. iScience 2025, 28, 112624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolte, S.; Cordelières, F.P. A Guided Tour into Subcellular Colocalization Analysis in Light Microscopy. J. Microsc. 2006, 224, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofroniew, N.; Burt, A.; Witz, G.; Abouakil, F.; Lambert, T. Napari Napari-Animation. Available online: https://github.com/napari/napari-animation (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Sun, Y.; Cao, C.; Peng, Y.; Dai, X.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Liang, T.; Song, P.; Ye, Y.; Yang, J.; et al. Application of Advanced Bioimaging Technologies in Viral Infections. Mater. Today Phys. 2024, 46, 101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobjev, I.A.; Chentsov, Y.S. Centrioles in the Cell Cycle. I. Epithelial Cells. J. Cell Biol. 1982, 98, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Draper, B.E.; Jarrold, M.F.; Heger, C.D. Insights into Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid Charge Heterogeneity. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 17132–17140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldt, C.L.; Skinner, M.A.; Anand, G.S. Structural Changes Likely Cause Chemical Differences between Empty and Full AAV Capsids. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, D.; Kern, A.; Rittner, K.; Kleinschmidt, J.A. Novel Tools for Production and Purification of Recombinant Adenoassociated Virus Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 1998, 9, 2745–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berghe, N.; Costermans, E.; Nuseibeh, S.; Brouns, T.; Van Hove, I.; Moeyaert, B.; Henckaerts, E. Quantification of Adeno-Associated Viral Genomes in Purified Vector Samples by Digital Droplet Polymerase Chain Reaction. J. Vis. Exp. 2024, 212, e67252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.M.; Toloudis, D.; Sherman, J.; Swain-Bowden, M.; Lambert, T.; AICSImageIO Contributors. AICSImageIO: Image Reading, Metadata Conversion, and Image Writing for Microscopy Images in Pure Python (Version 3.10). 2021. Available online: https://github.com/AllenCellModeling/aicsimageio (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Stringer, C.; Wang, T.; Michaelos, M.; Pachitariu, M. Cellpose: A Generalist Algorithm for Cellular Segmentation. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Walt, S.; Schönberger, J.L.; Nunez-Iglesias, J.; Boulogne, F.; Warner, J.D.; Yager, N.; Gouillart, E.; Yu, T. Scikit-Image: Image Processing in Python. PeerJ 2014, 2, e453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, D.B.; Caswell, T.; Keim, N.C.; Van der Wel, C.M.; Verweij, R.W. Zenodo: Soft-Matter/Trackpy:V0.6.4. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/12708864 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leysen, M.; Peredo, N.; Pavie, B.; Moeyaert, B.; Henckaerts, E. A Longitudinal 3D Live-Cell Imaging Platform to Uncover AAV Vector–Host Dynamics at Single-Cell Resolution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010236

Leysen M, Peredo N, Pavie B, Moeyaert B, Henckaerts E. A Longitudinal 3D Live-Cell Imaging Platform to Uncover AAV Vector–Host Dynamics at Single-Cell Resolution. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010236

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeysen, Marlies, Nicolas Peredo, Benjamin Pavie, Benjamien Moeyaert, and Els Henckaerts. 2026. "A Longitudinal 3D Live-Cell Imaging Platform to Uncover AAV Vector–Host Dynamics at Single-Cell Resolution" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010236

APA StyleLeysen, M., Peredo, N., Pavie, B., Moeyaert, B., & Henckaerts, E. (2026). A Longitudinal 3D Live-Cell Imaging Platform to Uncover AAV Vector–Host Dynamics at Single-Cell Resolution. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010236