Uncovering the Molecular Signatures of Rare Genetic Diseases in the Punjabi Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Incidence of RGDs

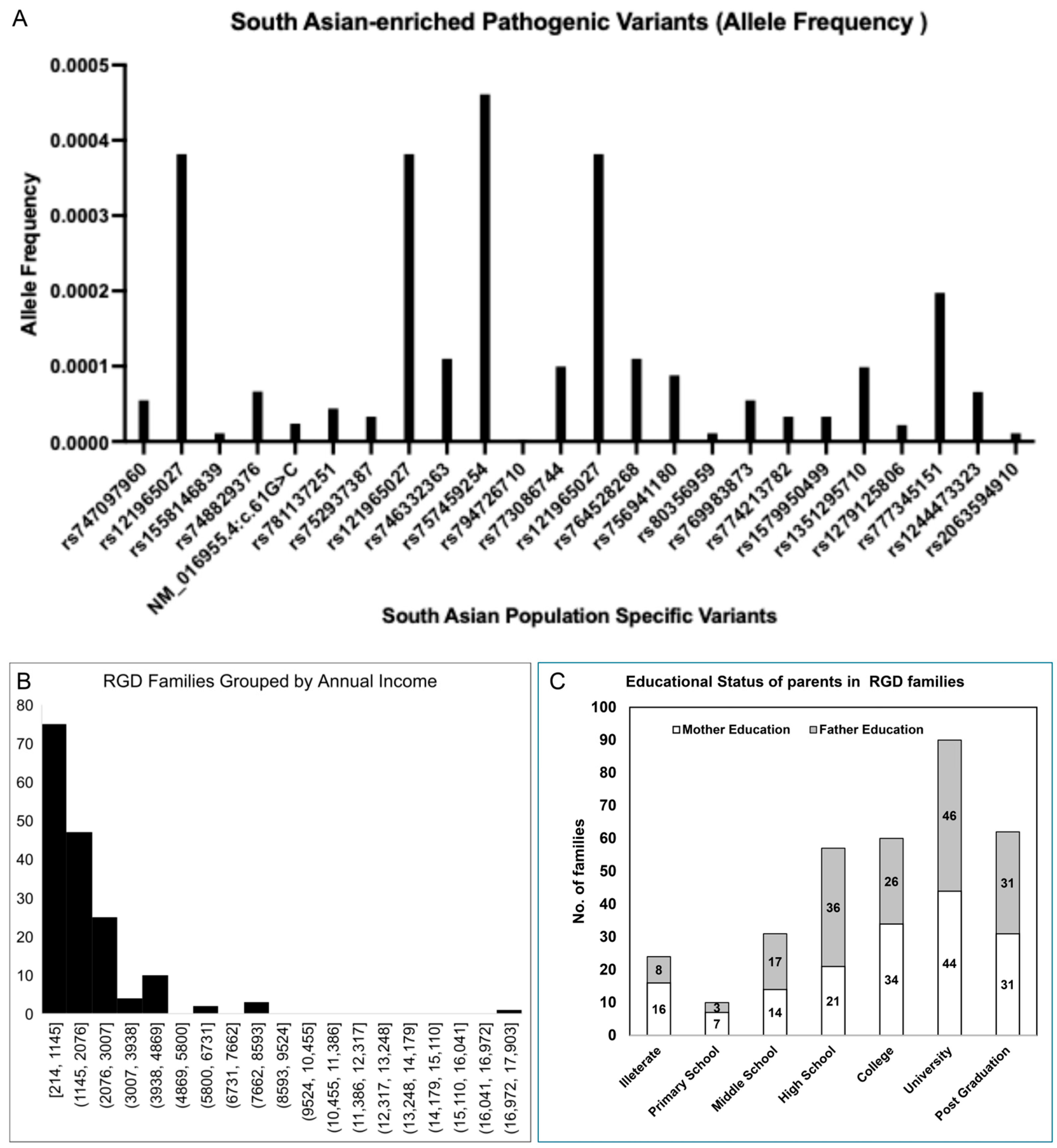

2.2. Epidemiological Profiling of RGD Carrier Families

2.3. RGD Burden Across Ethnic Groups

2.4. RGD Distribution Across Castes

2.5. Association of Consanguinity with RGDs

2.6. Molecular Epidemiology of RGDs in Current Registry

2.7. Association of Socioeconomic Demographics with RGDs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Settings

4.2. Sampling Technique

4.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

4.4. Patient Data Collection

4.5. Genetic Data

4.6. Genetic Methods

4.7. Healthy Controls Data

4.8. Consanguinity Analysis

4.9. Variant Annotation

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cipriani, V.; Vestito, L.; Magavern, E.F.; Jacobsen, J.O.B.; Arno, G.; Behr, E.R.; Benson, K.A.; Bertoli, M.; Bockenhauer, D.; Bowl, M.R.; et al. Rare disease gene association discovery in the 100,000 GenomesProject. Nature 2025. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguengang Wakap, S.; Lambert, D.M.; Olry, A.; Rodwell, C.; Gueydan, C.; Lanneau, V.; Murphy, D.; Le Cam, Y.; Rath, A. Estimating cumulative point prevalence of rare diseases: Analysis of the Orphanet database. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 28, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaiasu, V.; Nanu, M.; Matei, D. Rare Disease Day—At a glance. Maedica 2010, 5, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Iourov, I.Y.; Vorsanova, S.G.; Yurov, Y.B. Pathway-based classification of genetic diseases. Mol. Cytogenet. 2019, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.E.; Bergman, P.; Hagey, D.W. Estimating the number of diseases–the concept of rare, ultra-rare, and hyper-rare. Iscience 2022, 25, 104698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Marmiesse, A.; Gouveia, S.; Couce, M.L. NGS technologies as a turning point in rare disease research, diagnosis and treatment. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 404–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, A.; Sundaravadivel, P.; Dalal, A. Rare genetic diseases in India: Steps toward a nationwide mission program. J. Biosci. 2024, 49, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimova, B.; Storek, M.; Valis, M.; Kuca, K. Global view on rare diseases: A mini review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 3153–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wainstock, D.; Katz, A. Advancing rare disease policy in Latin America: A call to action. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2023, 18, 100434. [Google Scholar]

- Thevenon, J.; Duffourd, Y.; Masurel-Paulet, A.; Lefebvre, M.; Feillet, F.; El Chehadeh-Djebbar, S.; St-Onge, J.; Steinmetz, A.; Huet, F.; Chouchane, M. Diagnostic odyssey in severe neurodevelopmental disorders: Toward clinical whole-exome sequencing as a first-line diagnostic test. Clin. Genet. 2016, 89, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, S.D.; Avramović, V.; Maroilley, T.; Lehman, A.; Arbour, L.; Tarailo-Graovac, M. Rare disorders have many faces: In silico characterization of rare disorder spectrum. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, J. Rare Diseases: Understanding this Public Health Priority; European Organisation for Rare Diseases: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Janku, P.; Robinow, M.; Kelly, T.; Bralley, R.; Baynes, A.; Edgerton, M.T.; Opitz, J.M. The van der Woude syndrome in a large kindred: Variability, penetrance, genetic risks. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1980, 5, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.N.; Krawczak, M.; Polychronakos, C.; Tyler-Smith, C.; Kehrer-Sawatzki, H. Where genotype is not predictive of phenotype: Towards an understanding of the molecular basis of reduced penetrance in human inherited disease. Hum. Genet. 2013, 132, 1077–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, J.K.; Hariharan, M.; Bargaje, R.; Pillai, B.; Brahmachari, V. Incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity: Is there a microRNA connection? Bioessays 2009, 31, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, T.; Lemire, G.; Kernohan, K.D.; Howley, H.E.; Adams, D.R.; Boycott, K.M. New diagnostic approaches for undiagnosed rare genetic diseases. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2020, 21, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merker, J.D.; Wenger, A.M.; Sneddon, T.; Grove, M.; Zappala, Z.; Fresard, L.; Waggott, D.; Utiramerur, S.; Hou, Y.; Smith, K.S. Long-read genome sequencing identifies causal structural variation in a Mendelian disease. Genet. Med. 2018, 20, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuguchi, T.; Suzuki, T.; Abe, C.; Umemura, A.; Tokunaga, K.; Kawai, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Nagasaki, M.; Kinoshita, K.; Okamura, Y. A 12-kb structural variation in progressive myoclonic epilepsy was newly identified by long-read whole-genome sequencing. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 64, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsanis, S.H.; Katsanis, N. Molecular genetic testing and the future of clinical genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013, 14, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Tian, L.; Hakonarson, H. Increasing diagnostic yield by RNA-Sequencing in rare disease—Bypass hurdles of interpreting intronic or splice-altering variants. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, A.M.; Guturu, H.; Bernstein, J.A.; Bejerano, G. Systematic reanalysis of clinical exome data yields additional diagnoses: Implications for providers. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.S.; Ashino, R.; Oota, H.; Ishida, H.; Niimura, Y.; Touhara, K.; Melin, A.D.; Kawamura, S. Genetic variation of olfactory receptor gene family in a Japanese population. Anthropol. Sci. 2022, 130, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, A.T.; Oweis, L.; Al Qudah, A.; El-Shanti, H. Congenital muscle dystrophies: Role of singleton whole exome sequencing in countries with limited resources. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2022, 217, 107271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frésard, L.; Montgomery, S.B. Diagnosing rare diseases after the exome. Mol. Case Stud. 2018, 4, a003392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, A.N.; Gallagher, R.C.; Wang, Y.; Currier, R.J.; Amatuni, G.; Bassaganyas, L.; Chen, F.; Kundu, K.; Kvale, M.; Mooney, S.D. The role of exome sequencing in newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1392–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woerner, A.C.; Gallagher, R.C.; Vockley, J.; Adhikari, A.N. The use of whole genome and exome sequencing for newborn screening: Challenges and opportunities for population health. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lu, Q.; Zhao, H. A review of study designs and statistical methods for genomic epidemiology studies using next generation sequencing. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 100,000 Genomes Project Pilot Investigators. 100,000 genomes pilot on rare-disease diagnosis in health care—Preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1868–1880. [CrossRef]

- Manickam, K.; McClain, M.R.; Demmer, L.A.; Biswas, S.; Kearney, H.M.; Malinowski, J.; Massingham, L.J.; Miller, D.; Yu, T.W.; Hisama, F.M. Exome and genome sequencing for pediatric patients with congenital anomalies or intellectual disability: An evidence-based clinical guideline of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 2029–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinowski, J.; Miller, D.T.; Demmer, L.; Gannon, J.; Pereira, E.M.; Schroeder, M.C.; Scheuner, M.T.; Tsai, A.C.-H.; Hickey, S.E.; Shen, J. Systematic evidence-based review: Outcomes from exome and genome sequencing for pediatric patients with congenital anomalies or intellectual disability. Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 986–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, T.A.; Feng, X.; Keisler, M.; Cohen, J.T.; Neumann, P.J.; Prichard, D.; Schroeder, B.E.; Salyakina, D.; Espinal, P.S.; Weidner, S.B. Cost-effectiveness of exome and genome sequencing for children with rare and undiagnosed conditions. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 1349–1361, Erratum in Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 2415–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, B.J.; Hu, J.; Reilly, M.P.; Li, M. Applications of single-cell genomics and computational strategies to study common disease and population-level variation. Genome Res. 2021, 31, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarailo-Graovac, M.; Shyr, C.; Ross, C.J.; Horvath, G.A.; Salvarinova, R.; Ye, X.C.; Zhang, L.-H.; Bhavsar, A.P.; Lee, J.J.; Drögemöller, B.I. Exome sequencing and the management of neurometabolic disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 2246–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, N.; Martineau, F.; Manacorda, T. Diagnostic Odyssey for Rare Diseases: Exploration of Potential Indicators; Policy Innovation Research Unit (PIRU): London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, N.; Tsipis, J.; Windmueller, G.; Mandel, L.; Estrella, E. “Is it going to hurt?”: The impact of the diagnostic odyssey on children and their families. J. Genet. Couns. 2015, 24, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.M.; Hildreth, A.; Batalov, S.; Ding, Y.; Chowdhury, S.; Watkins, K.; Ellsworth, K.; Camp, B.; Kint, C.I.; Yacoubian, C. Diagnosis of genetic diseases in seriously ill children by rapid whole-genome sequencing and automated phenotyping and interpretation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaat6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnaes, L.; Hildreth, A.; Sweeney, N.M.; Clark, M.M.; Chowdhury, S.; Nahas, S.; Cakici, J.A.; Benson, W.; Kaplan, R.H.; Kronick, R. Rapid whole-genome sequencing decreases infant morbidity and cost of hospitalization. NPJ Genom. Med. 2018, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.J.; Niemi, A.-K.; Dimmock, D.P.; Speziale, M.; Nespeca, M.; Chau, K.K.; Van Der Kraan, L.; Wright, M.S.; Hansen, C.; Veeraraghavan, N. Rapid sequencing-based diagnosis of thiamine metabolism dysfunction syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2159–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, E.F.; Clark, M.M.; Farnaes, L.; Williams, M.R.; Perry, J.C.; Ingulli, E.G.; Sweeney, N.M.; Doshi, A.; Gold, J.J.; Briggs, B. Rapid whole genome sequencing has clinical utility in children in the PICU. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 20, 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willig, L.K.; Petrikin, J.E.; Smith, L.D.; Saunders, C.J.; Thiffault, I.; Miller, N.A.; Soden, S.E.; Cakici, J.A.; Herd, S.M.; Twist, G. Whole-genome sequencing for identification of Mendelian disorders in critically ill infants: A retrospective analysis of diagnostic and clinical findings. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015, 3, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, A.R.; Mentzakis, E.; Archangelidi, O.; Paolucci, F. The economic and health impact of rare diseases: A meta-analysis. Health Policy Technol. 2021, 10, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittles, A.H.; Black, M.L. Consanguinity, human evolution, and complex diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsy, A.S.; Al-Jaser, M.H.; Albdass, A.; Al-Daihan, S.; Alanazi, M. Is consanguinity prevalence decreasing in Saudis?: A study in two generations. Afr. Health Sci. 2014, 14, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudejaja, A.; Khan, M.A.; Singh, R.; Toweir, A.A.; Narayanappa, M.; Gupta, B.; Umer, S. Experience of a family clinic at Benghazi, Libya, and sociomedical aspects of its catchment population. Fam. Pract. 1987, 4, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bener, A.; Alali, K.A. Consanguineous marriage in a newly developed country: The Qatari population. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2006, 38, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.S.; Aslamkhan, M.; Zar, M.S.; Hanif, A.; Haris, A.R. Dichromacy: Color Vision Impairment and Consanguinity in Heterogenous Population of Pakistan. Int. J. Front. Sci. 2019, 3, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, N.; Bittles, A.H.; Petherick, E.S.; Wright, J. Endogamy, consanguinity and the health implications of changing marital choices in the UK Pakistani community. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2017, 49, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liascovich, R.; Rittler, M.; Castilla, E.E. Consanguinity in South America: Demographic aspects. Hum. Hered. 2000, 51, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, J.M.; O’Rourke, D.H. Geographic distribution of consanguinity in Europe. Ann. Hum. Biol. 1986, 13, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslamkhan, M.; Ali, A.; Barnett, H. Consanguineous marriages in rural west Pakistan. Annu. Rep. Univ. Med. Sch. ICMRT 1969, 69, 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, M.S.; Akhtar, M.S.; Haris, A.R.; Aslamkhan, M. Colour Vision Deficiency and Consanguinity in Pakistani Pukhtoon Population. Adv. Life Sci. 2020, 7, 237–239. [Google Scholar]

- Wasim, M.; Khan, H.N.; Ayesha, H.; Awan, F.R. Need and Challenges in Establishing Newborn Screening Programs for Inherited Metabolic Disorders in Developing Countries. Adv. Biol. 2023, 7, e2200318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslamkhan, M.; Qadeer, M.I.; Akhtar, M.S.; Chudhary, S.A.; Mariam, M.; Ali, Z.; Khalid, A.; Irfan, M.; Khan, Y. Cultural consanguinity as cause of β-thalassemia prevalence in population. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romdhane, L.; Mezzi, N.; Hamdi, Y.; El-Kamah, G.; Barakat, A.; Abdelhak, S. Consanguinity and inbreeding in health and disease in North African populations. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2019, 20, 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akthar, M.S. Role of epidemiological studies in disease prevention. Int. J. Front. Sci. 2019, 3, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohyuddin, A.; Ayub, Q.; Khaliq, S.; Mansoor, A.; Mazhar, K.; Rehman, S.; Mehdi, S.Q. HLA polymorphism in six ethnic groups from Pakistan. Tissue Antigens 2002, 59, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Sahoo, H. Consanguineous marriages in India: Prevalence and determinants. J. Health Manag. 2021, 23, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanim, M.; Mosleh, R.; Hamdan, A.; Amer, J.; Alqub, M.; Jarrar, Y.; Dwikat, M. Assessment of perceptions and predictors towards consanguinity: A cross-sectional study from Palestine. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 3443–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.T.; Lee, K.; Chung, W.K.; Gordon, A.S.; Herman, G.E.; Klein, T.E.; Stewart, D.R.; Amendola, L.M.; Adelman, K.; Bale, S.J.; et al. ACMG SF v3.0 list for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing: A policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 1381–1390, Erratum in Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 1582–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenk, M.K.; Naz, S.; Chaudhry, T. Intensive kinship, development, and demography: Why Pakistan has the highest rates of cousin marriage in the world. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2024, 50, 1045–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, A.; Naqvi, S.F.; Syed, A.; Zainab, S.; Sohail, K.; Malik, S. Burden of Congenital and Hereditary Anomalies in Hazara Population of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 38, 1278–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.F.; Ameena, U.; Qazi, W.U.; Ahmad, S.; Iqbal, A.; Malik, S. Burden of congenital and hereditary anomalies and their epidemiological attributes in the pediatric and adult population of Peshawar valley, Pakistan. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 40, 2181–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azmatullah; Khan, M.Q.; Jan, A.; Mehmood, J.; Malik, S. Prevalence-pattern of congenital and hereditary anomalies in Balochistan Province of Pakistan. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 40, 1898–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti, N.A.; Mumtaz, S.; Malik, S. Epidemiological study of congenital and hereditary anomalies in Sialkot District of Pakistan revealed a high incidence of limb and neurological disorders. Population 2019, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Siddiqui, A.; Mughal, M.; Naz, S.; Wajid, M.; Malik, S. Congenital anomalies in Okara District of Pakistan: Epidemiology, spectrum and ethno-demographic inequalities. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 41, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Naeem, M. A systematic review of hereditary neurological disorders diagnosed by whole exome sequencing in Pakistani population: Updates from 2014 to November 2024. Neurogenetics 2025, 26, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.R. The burden of rare diseases. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2019, 179, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambello, M.J.; Li, H. Current strategies for the treatment of inborn errors of metabolism. J. Genet. Genom. 2018, 45, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Lozano, A.; Villamandos García, D.; Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Fiuza-Luces, C.; Pareja-Galeano, H.; Garatachea, N.; Nogales Gadea, G.; Lucia, A. Niemann-Pick disease treatment: A systematic review of clinical trials. Ann. Transl. Med. 2015, 3, 360. [Google Scholar]

- Matencio, A.; Navarro-Orcajada, S.; González-Ramón, A.; García-Carmona, F.; López-Nicolás, J.M. Recent advances in the treatment of Niemann pick disease type C: A mini-review. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 584, 119440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomes, K.M.; Squires, R.H.; Kelly, D.; Rajwal, S.; Soufi, N.; Lachaux, A.; Jankowska, I.; Mack, C.; Setchell, K.D.; Karthikeyan, P. Maralixibat for the treatment of PFIC: Long-term, IBAT inhibition in an open-label, Phase 2 study. Hepatol. Commun. 2022, 6, 2379–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaydin, M.; Bozkurter Cil, A.T. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis: Diagnosis, management, and treatment. Hepatic Med. Evid. Res. 2018, 10, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingma, S.D.K.; Jonckheere, A.I. MPS I: Early diagnosis, bone disease and treatment, where are we now? J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2021, 44, 1289–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, M.; Hoshina, H.; Sawamoto, K.; Kubaski, F.; Mason, R.W.; Mackenzie, W.G.; Theroux, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Yamaguchi, S.; Suzuki, Y.; et al. Critical review of current MPS guidelines and management. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 126, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Population Studies. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey, 2017–2018; National Institute of Population Studies: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, S.N.; Midhet, F.; Uzma, Q.; Thom, E.M.; Baqai, S.; Khan, M.T.; Memon, A. Factors associated with induced abortions in Pakistan: A comprehensive analysis of Pakistan maternal mortality survey 2019. Front. Reprod. Health 2025, 7, 1536582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathar, Z.; Singh, S.; Shah, I.H.; Niazi, M.R.; Parveen, T.; Mulhern, O.; Mir, A.M. Abortion and unintended pregnancy in Pakistan: New evidence for 2023 and trends over the past decade. BMJ Glob. Health 2025, 10, e017239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathar, Z.A.; Singh, S.; Fikree, F.F. Estimating the Incidence of Abortion in Pakistan. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2007, 38, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Amin-ud-Din, M. Genetic heterogeneity and gene diversity at ABO and Rh loci in the human population of southern Punjab, Pakistan. Pak. J. Zool. 2013, 45, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Aftab, H.; Ambreen, A.; Jamil, M.; Garred, P.; Petersen, J.H.; Nielsen, S.D.; Bygbjerg, I.C.; Christensen, D.L. High prevalence of diabetes and anthropometric heterogeneity among tuberculosis patients in Pakistan. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2017, 22, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid Hussain, M.; Marriam Bakhtiar, S.; Farooq, M.; Anjum, I.; Janzen, E.; Reza Toliat, M.; Eiberg, H.; Kjaer, K.; Tommerup, N.; Noegel, A. Genetic heterogeneity in Pakistani microcephaly families. Clin. Genet. 2013, 83, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gila-Kochanowski, V. Aryan and Indo-Aryan Migrations. Diogenes 1990, 38, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, V. What is the Aryan Migration Theory? 2000. Available online: https://omilosmeleton.gr/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Migration_Theory.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Witzel, M. Early ‘Aryans’ and their neighbors outside and inside India. J. Biosci. 2019, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.K.; Kadian, A.; Kushniarevich, A.; Montinaro, F.; Mondal, M.; Ongaro, L.; Singh, M.; Kumar, P.; Rai, N.; Parik, J.; et al. The Genetic Ancestry of Modern Indus Valley Populations from Northwest India. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 103, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofied, E.A.; Abo-Elkheir, O.I.; Gaber, K.R.; Abd El Fattah, T.A. The effect of consanguineous marriage on reproductive wastage and Perinatal outcomes. J. Recent. Adv. Med. 2024, 5, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Goundali, K.; Chebabe, M.; Zahra Laamiri, F.; Hilali, A. The Determinants of Consanguineous Marriages among the Arab Population: A Systematic Review. Iran. J. Public Health 2022, 51, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaban, F.A.; Aldosari, M.; Ghazal, I.; Al-Shammari, H.; ElHag, S.; Thompson, I.R.; Bruder, J.; Shaath, H.; Al-Faraj, F.; Tolefat, M.; et al. Consanguinity as a Risk Factor for Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2025, 55, 1945–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, G.; Rusu, C.; Maștaleru, A.; Oancea, A.; Cumpăt, C.M.; Luca, M.C.; Grosu, C.; Leon, M.M. Social and Demographic Determinants of Consanguineous Marriage: Insights from a Literature Review. Genealogy 2025, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouritorghabeh, H. Consanguineous marriage and rare bleeding disorders. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2021, 14, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weymann, D.; Buckell, J.; Fahr, P.; Loewen, R.; Ehman, M.; Pollard, S.; Friedman, J.M.; Stockler-Ipsiroglu, S.; Elliott, A.M.; Wordsworth, S.; et al. Health Care Costs After Genome-Wide Sequencing for Children With Rare Diseases in England and Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2420842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akesson, L.S.; Parekh, S.; Alderdice, A.; Jackson, H.; Bain, L.; Dudgeon, A.; Williamson, L.J.; Akesson, B.L.; Say, G.; Kellett, M.J.; et al. Developing best practice rare disease diagnostic care models in a real-world rural/regional setting. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaubitz, R.; Heinrich, L.; Tesch, F.; Seifert, M.; Reber, K.C.; Marschall, U.; Schmitt, J.; Müller, G. The cost of the diagnostic odyssey of patients with suspected rare diseases. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, Q.; Alharthi, M.T.H.; Alahmari, S.A.S.; Khan, T.; Abbas, M.; Latif, M.; Jelani, M. Whole exome sequencing: Unlocking the molecular diagnostic odyssey in Pakhtun ethnic group of Pakistani population. Gene 2025, 962, 149586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, M.A.; Gul, W.; Abrejo, F. Cost of primary health care in Pakistan. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2015, 27, 88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Razzak, J.A.; Bhatti, J.A.; Ali, M.; Khan, U.R.; Jooma, R. Average out-of-pocket healthcare and work-loss costs of traffic injuries in Karachi, Pakistan. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2011, 18, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tournebize, R.; Chu, G.; Moorjani, P. Reconstructing the history of founder events using genome-wide patterns of allele sharing across individuals. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdoncuff, E.; Skov, L.; Patterson, N.; Banerjee, J.; Khobragade, P.; Chakrabarti, S.S.; Chakrawarty, A.; Chatterjee, P.; Dhar, M.; Gupta, M.; et al. 50,000 years of evolutionary history of India: Impact on health and disease variation. Cell 2025, 188, 3389–3404.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, S.T.; Ward, M.; Sirotkin, K. dbSNP-database for single nucleotide polymorphisms and other classes of minor genetic variation. Genome Res. 1999, 9, 677–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Diagnoses Made by Short and Structural Variant Discovery Methods | ||

|---|---|---|

| Short Variant Discovery | Structural/Copy Number Variation | |

| Short Variant Discovery | 91 | 35 |

| Copy Number Variation | 35 | 35 |

| Sequencing Techniques Utilized for Diagnosis | ||

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Whole Exome Sequencing | Targeted Capture Sequencing |

| 8 | 56 | 27 |

| Variant Class | Primary Variants | Secondary Variants | Variants Of Unknown Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frameshift Likely Pathogenic | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Frameshift Pathogenic | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| In Frame Pathogenic | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| In Frame Uncertain Significance | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Large Inversion | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Likely Pathogenic | 5 | 11 | 0 |

| Loss Like Pathogenic | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Loss Pathogenic | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Missense Pathogenic | 18 | 18 | 0 |

| Missense Likely Pathogenic | 14 | 6 | 0 |

| Missense Uncertain Significance | 13 | 7 | 20 |

| Nonsense Pathogenic | 12 | 1 | 0 |

| Nonsense Likely Pathogenic | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| Pathogenic | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Silent Pathogenic | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Silent Uncertain Significance | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Splicing Likely Pathogenic | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Splicing Pathogenic | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Splicing Uncertain Significance | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Vus | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Total | 91 | 58 | 31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tabassum, I.; Shafique, M.; Akhtar, M.S. Uncovering the Molecular Signatures of Rare Genetic Diseases in the Punjabi Population. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010206

Tabassum I, Shafique M, Akhtar MS. Uncovering the Molecular Signatures of Rare Genetic Diseases in the Punjabi Population. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010206

Chicago/Turabian StyleTabassum, Iqra, Muhammad Shafique, and Muhammad Shoaib Akhtar. 2026. "Uncovering the Molecular Signatures of Rare Genetic Diseases in the Punjabi Population" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010206

APA StyleTabassum, I., Shafique, M., & Akhtar, M. S. (2026). Uncovering the Molecular Signatures of Rare Genetic Diseases in the Punjabi Population. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010206