AI-Guided Multi-Omic Microbiome Modulation Improves Clinical and Inflammatory Outcomes in Refractory IDB: A Real-World Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Study Population

4.2. Baseline Multi-Omic Assessment

- Stool metagenomic sequencing using Illumina NovaSeq technology, with comprehensive taxonomic, functional, and resistome annotation.

- Blood biomarker profiling, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and a targeted micronutrient panel (vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron, zinc, calcium).

- Digital lifestyle and symptom assessment, capturing medical history, dietary habits, medication exposure, and prior flare patterns through a structured online questionnaire.

4.3. AI-Driven Personalized Intervention

4.4. Data Collection and Monitoring

- Precision dietary guidance, adjusting macronutrient ratios and excluding patient-specific pro-inflammatory foods.

- Tailored symbiotic formulations, consisting of strain-level probiotics and prebiotic fibers selected to enhance beneficial microbial functions.

- Targeted antimicrobials or phage therapy applied only when pathogenic signatures exceeded defined thresholds.

- Micronutrient correction for documented deficiencies identified through baseline multi-omic assessment.

4.5. Outcome Measures

4.6. Statistical Analysis

4.7. Ethical Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDowell, C.; Farooq, U.; Haseeb, M. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Zhang, C.; Gong, R.; Jiang, W.; Ding, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhu, M.; Zuo, J.; Huang, X.; et al. From West to East: Dissecting the Global Shift in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Burden and Projecting Future Scenarios. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdin, M.; Zarei, L.; Bagheri Lankarani, K.; Ghahramani, S. The Cost of Illness Analysis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, G.; Pugliese, D.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F.; Neri, M.; Guidi, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; Armuzzi, A. Novel Trends with Biologics in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Sequential and Combined Approaches. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 17562848211006669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annese, V.; Nathwani, R.; Alkhatry, M.; Al-Rifai, A.; Al Awadhi, S.; Georgopoulos, F.; Jazzar, A.N.; Khassouan, A.M.; Koutoubi, Z.; Taha, M.S.; et al. Optimizing Biologic Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Delphi Consensus in the United Arab Emirates. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 17562848211065329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jucan, A.E.; Gavrilescu, O.; Dranga, M.; Popa, I.V.; Mihai, I.R.; Mihai, V.C.; Stefanescu, G.; Drug, V.L.; Prelipcean, C.C.; Vulpoi, R.A.; et al. Evaluation of Disease Activity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Diagnostic Tools in the Assessment of Histological Healing. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delano, M.J.; Ward, P.A. The Immune System’s Role in Sepsis Progression, Resolution, and Long-Term Outcome. Immunol. Rev. 2016, 274, 330–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travis, S. Current Paradigms in the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Singap. Med. J. 2025, 66, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubatan, J.; Boye, T.L.; Temby, M.; Sojwal, R.S.; Holman, D.R.; Sinha, S.R.; Rogalla, S.R.; Nielsen, O.H. Gut Microbiome in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Role in Pathogenesis, Dietary Modulation, and Colitis-Associated Colon Cancer. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Fan, N.; Ma, S.X.; Cheng, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, G. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Pathogenesis, Diseases, Prevention, and Therapy. MedComm 2025, 6, e70168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Shen, J.; Ran, Z.H. Association between Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Reduction and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of the Literature. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2014, 2014, 872725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, A.D.; Xavier, R.J.; Gevers, D. The Microbiome in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current Status and the Future Ahead. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorsand, B.; Asadzadeh Aghdaei, H.; Nazemalhosseini-Mojarad, E.; Nadalian, B.; Nadalian, B.; Houri, H. Overrepresentation of Enterobacteriaceae and Escherichia coli Is the Major Gut Microbiome Signature in Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Comprehensive Metagenomic Analysis of IBDMDB Datasets. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1015890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera-Fernández, N.; Candela-González, J.; Orenes-Piñero, E. Probiotics, Prebiotics, Fecal Microbiota Transplantation, and Dietary Patterns in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2400429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Yao, Q.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Meng, Q.; Ji, J.; Yu, Z.; Chen, X. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Application Scenarios, Efficacy Prediction, and Factors Impacting Donor–Recipient Interplay. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1556827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N. The Need for Personalized Approaches to Microbiome Modulation. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, H.A.; Savidge, T.C. Gut Microbiome Metagenomics in Clinical Practice: Bridging the Gap between Research and Precision Medicine. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2569739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeevi, D.; Korem, T.; Zmora, N.; Israeli, D.; Rothschild, D.; Weinberger, A.; Ben-Yacov, O.; Lador, D.; Avnit-Sagi, T.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; et al. Personalized Nutrition by Prediction of Glycemic Responses. Cell 2015, 163, 1079–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J.N.; Falcone, G.J.; Rajpurkar, P.; Topol, E.J. Multimodal Biomedical AI. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1773–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, Y.; Kim, J.; Jung, S.H.; Woerner, J.; Suh, E.H.; Lee, D.G.; Shivakumar, M.; Lee, M.E.; Kim, D. Harnessing Artificial Intelligence in Multimodal Omics Data Integration: Paving the Path for the Next Frontier in Precision Medicine. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 2024, 7, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, A.L.; Shung, D.; Stidham, R.W.; Kochhar, G.S.; Iacucci, M. How Artificial Intelligence Will Transform Clinical Care, Research, and Trials for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 23, 428–439.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Zmora, N.; Weissbrod, O.; Bar, N.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; Avnit-Sagi, T.; Kosower, N.; Malka, G.; Rein, M.; et al. Bread Affects Clinical Parameters and Induces Gut Microbiome-Associated Personal Glycemic Responses. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1243–1253.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhann, F.; Vila, A.V.; Bonder, M.J.; Fu, J.; Gevers, D.; Visschedijk, M.C.; Spekhorst, L.M.; Alberts, R.; Franke, L.; van Dullemen, H.M.; et al. Interplay of Host Genetics and Gut Microbiota Underlying the Onset and Clinical Presentation of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut 2018, 67, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol, H.; Landman, C.; Seksik, P.; Berard, L.; Montil, M.; Nion-Larmurier, I.; Bourrier, A.; Le Gall, G.; Lalande, V.; De Rougemont, A.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation to Maintain Remission in Crohn’s Disease: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Study. Microbiome 2020, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutgeerts, P.; Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B.G.; Reinisch, W.; Olson, A.; Johanns, J.; Travers, S.; Rachmilewitz, D.; Hanauer, S.B.; Lichtenstein, G.; et al. Infliximab for Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2462–2476, Correction in N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2200. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMx060025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborn, W.J.; van Assche, G.; Reinisch, W.; Colombel, J.F.; D’Haens, G.; Wolf, D.C.; Kron, M.; Lazar, A.; Thakkar, R.B. Adalimumab Induces and Maintains Clinical Remission in Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis: Results of the ULTRA 2 Trial. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 257–265.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godala, M.; Gaszyńska, E.; Zatorski, H.; Małecka-Wojciesko, E. Dietary Interventions in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.; Tong, X.; Wang, R.; Song, X. The Clinical Effects of Probiotics for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e13792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseira, J.; Sousa, H.T.; Marreiros, A.; Contente, L.F.; Magro, F. Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: Translation and Validation to the Portuguese Language. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Arze, C.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Schirmer, M.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Poon, T.W.; Andrews, E.; Ajami, N.J.; Bonham, K.S.; Brislawn, C.J.; et al. Multi-Omics of the Gut Microbial Ecosystem in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Nature 2019, 569, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzosa, E.A.; Sirota-Madi, A.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Fornelos, N.; Haiser, H.J.; Reinker, S.; Vatanen, T.; Hall, A.B.; Mallick, H.; McIver, L.J.; et al. Gut Microbiome Structure and Metabolic Activity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 293–305, Correction in Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Dong, C.; Lv, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, W.; Jamali, M.; Abedi, R. Probiotics and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Umbrella Meta-Analysis of Relapse, Recurrence, and Remission Outcomes. Nutr. Metab. 2025, 22, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrador-López, M.; Martín-Masot, R.; Navas-López, V.M. Dietary Interventions in Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review of the Evidence with Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preidis, G.A.; Weizman, A.V.; Kashyap, P.C.; Morgan, R.L. AGA Technical Review on the Role of Probiotics in the Management of Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 708–738.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tričković, M.; Kieser, S.; Zdobnov, E.M.; Trajkovski, M. Subspecies of the Human Gut Microbiota Carry Implicit Information for In-Depth Microbiome Research. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 1446–1458.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiels, K.; Joossens, M.; Sabino, J.; De Preter, V.; Arijs, I.; Eeckhaut, V.; Ballet, V.; Claes, K.; Van Immerseel, F.; Verbeke, K.; et al. A Decrease of the Butyrate-Producing Species Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Defines Dysbiosis in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Gut 2014, 63, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Hold, G.; Flint, H. The Gut Microbiota, Bacterial Metabolites and Colorectal Cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajic, D.; Niemann, A.; Hillmer, A.; Mejías-Luque, R.; Bluemel, S.; Haller, D. Akkermansia muciniphila Strengthens the Intestinal Epithelial Barrier and Modulates Host Immune Responses. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 240–256.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiippala, K.; Kainulainen, V.; Kalliomäki, M.; Arkkila, P.; Satokari, R. Mucosal Homeostasis Is Maintained by Akkermansia muciniphila and Other Short-Chain Fatty Acid–Producing Commensals. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramsothy, S.; Nielsen, S.; Kamm, M.A.; Deshpande, N.P.; Faith, J.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Paramsothy, R.; Walsh, A.J.; van den Bogaerde, J.; Samuel, D.; et al. Specific Bacteria and Metabolites Associated with Response to Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1440–1454.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, S.P.; Hughes, P.A.; Waters, O.; Bryant, R.V.; Vincent, A.D.; Blatchford, P.; Katsikeros, R.; Makanyanga, J.; Campaniello, M.A.; Mavrangelos, C.; et al. Effect of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation on 8-Week Remission in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeltino, A.; Hatem, D.; Serantoni, C.; Riente, A.; De Giulio, M.M.; De Spirito, M.; De Maio, F.; Maulucci, G. Unraveling the Gut Microbiota: Implications for Precision Nutrition and Personalized Medicine. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, W. Dietary Diversity, Microbial Synthesis, and Human Health. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Zheng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Sang, L.; Zhu, J.; Luo, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, K.; et al. Intermediate Role of Gut Microbiota in Vitamin B Nutrition and Its Influences on Human Health. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1031502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, X. Mechanisms and Implications of the Gut Microbial Fermentation of Dietary Fibres for Human Health. Nat. Metab. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Sandborn, W.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; Bemelman, W.; Bryant, R.V.; D’Haens, G.; Dotan, I.; Dubinsky, M.; Furfaro, F.; et al. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE-II): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombel, J.F.; Narula, N.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Management Strategies to Improve Outcomes of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, N.; Vuyyuru, S.K.; Kedia, S.; Sahu, P.; Kante, B.; Kumar, P.; Ranjan, M.K.; Singh, M.K.; Kumar, S.; Sachdev, V.; et al. Correlation of fecal calprotectin and patient-reported outcome measures in patients with ulcerative colitis. Intest. Res. 2022, 20, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Panés, J.; Sandborn, W.J.; Vermeire, S.; Danese, S.; Feagan, B.G.; Colombel, J.F.; Hanauer, S.B.; Rycroft, B. Defining Disease Severity in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Current and Future Directions. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 348–354.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, E.A.; Labus, J.S.; Tillisch, K.; Cole, S.W.; Baldi, P. Towards a Systems View of IBS. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, S.P.; Waters, O.; Bryant, R.V.; Katsikeros, R.; Makanyanga, J.; Schoeman, M.N. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Ulcerative Colitis: Efficacy, Safety, and Predictors of Response. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 1550–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, S.H.; Maier, L. Artificial Intelligence in Microbiome Research: From Multi-Omics Integration to Personalized Therapeutics. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 2045–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, S.P.; Hughes, P.A.; Waters, O.; Bryant, R.V.; Vincent, A.D.; Blatchford, P.; Katsikeros, R.; Makanyanga, J.; Campaniello, M.A.; Mavrangelos, C.; et al. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Ulcerative Colitis: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 58, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gili, L.; Panaccione, R.; Steinhart, A.H.; Kaplan, G.G.; Xavier, R.J.; Vermeire, S. Shared Microbial and Metabolic Pathways Define Common Mechanisms in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 45–61.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, E.A.; Nance, K.; Chen, S. The Gut-Brain Axis. Annu. Rev. Med. 2022, 73, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, I.D.; Cadwell, K.; Huttenhower, C. Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanisms of Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Opportunities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2025, 25, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dunleavy, K.A.; Raffals, L.E.; Camilleri, M. Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Underpinning Pathogenesis and Therapeutics. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 4306–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, C.; Wang, Z.; Xuan, B.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yan, Y.; et al. Microbiome and Metabolome Features in Inflammatory Bowel Disease via Multi-Omics Integration Analyses across Cohorts. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, I.; Chomon-García, M.; Tomás-Aguirre, F.; Palau-Ferré, A.; Legidos-García, M.E.; Murillo-Llorente, M.T.; Pérez-Bermejo, M. Therapeutic and Immunologic Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacucci, M. Artificial Intelligence–Driven Personalized Medicine in IBD: From Multi-Omics Integration to Adaptive Care. Gastroenterology, 2025; 168, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Gomollón, F.; Dignass, A.; Annese, V.; Tilg, H.; Van Assche, G.; Lindsay, J.O.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Cullen, G.J.; Daperno, M.; Kucharzik, T.; et al. 3rd European Evidence-Based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1—Diagnosis and Medical Management. J. Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.T.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Siegel, C.A.; Sauer, B.G.; Long, M.D. ACG Clinical Guideline: Ulcerative Colitis in Adults. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 384–413, Erratum in Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 120, 1187–1224. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000003463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2019.

- Vaidya, S.R.; Aeddula, N.R. Chronic Kidney Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| N (IBD total) | 358 |

| Ulcerative Colitis ** | 215 (60.0%) |

| Crohn’s Disease ** | 143 (40.0%) |

| Age (years) * | 42.7 ± 15.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) * | 24.5 ± 6.2 |

| Male ** | 187 (52.2%) |

| Female ** | 171 (47.8%) |

| Therapy category | |

| Biologics ** | 242 (67.6%) |

| Steroids ** | 81 (22.6%) |

| Immunomodulators ** | 12 (3.4%) |

| Antibiotic ** | 12 (3.4%) |

| Nutrition ** | 9 (2.5%) |

| 5-ASA ** | 2 (0.5%) |

| Measure | Value |

|---|---|

| Stool frequency (baseline) | 8.87 ± 2.05 |

| Stool frequency (Month 3) | 2.76 ± 1.11 |

| Change (Month 3-baseline) | −6.11 (p < 0.001) |

| Blood in stool (Absent, n/N) | 327/358 |

| Urgency resolved (n/N) | 327/358 |

| Overall response: Much Improved (n, %) | 256 (71.5%) |

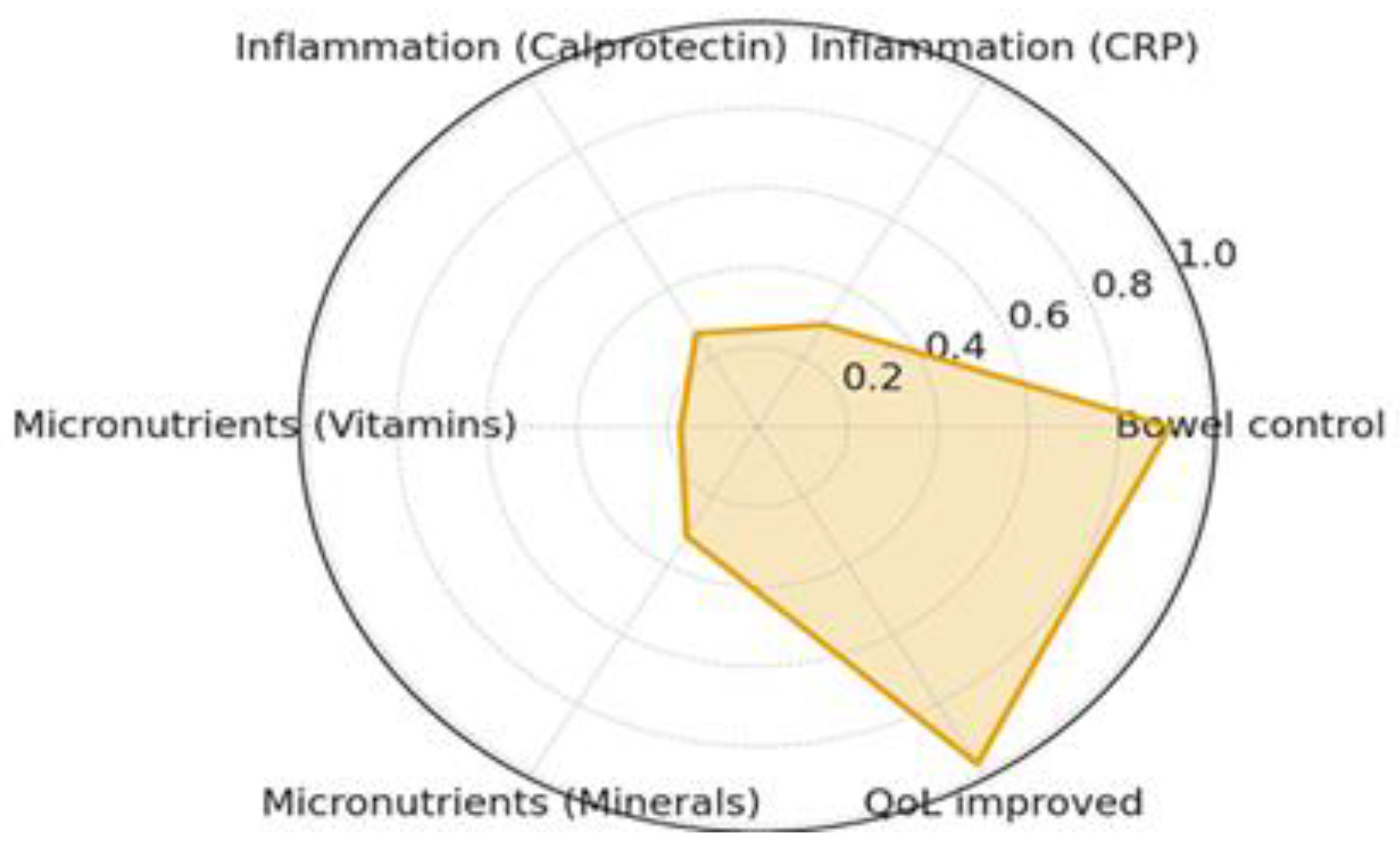

| Biomarker | Abnormal at Baseline (n) | Normalized at Month 3 (n) | Normalization Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRP (hs-CRP) | 221 | 201 | 91.0 |

| Fecal Calprotectin | 224 | 196 | 87.5 |

| Vitamins (B/D) | 193 | 61 | 31.6 |

| Minerals (Iron/Zinc/etc.) | 143 | 113 | 79.0 |

| Taxon | N with Data | Improved (n) | Improved (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akkermansia muciniphila | 358 | 77 | 21.5 |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | 358 | 139 | 38.8 |

| Bifidobacterium longum | 358 | 276 | 77.1 |

| Roseburia intestinalis | 358 | 109 | 30.4 |

| Eubacterium rectale | 358 | 67 | 18.7 |

| Ruminococcus bromii | 358 | 20 | 5.6 |

| Confirmed diagnosis | Documented diagnosis of UC or CD established by endoscopic, histologic, or radiologic evidence consistent with current international guidelines (ECCO/AGA) [61,62]. |

| Disease duration of at least 24 months prior to baseline sampling, ensuring a chronic and stable diagnostic classification. | |

| Disease activity and treatment history | History of inadequate response, secondary loss of response, or intolerance to at least three previous therapeutic regimens, which may include:

|

| Patients may continue their stable maintenance therapy (if tolerated) during the study, provided no dose adjustments occurred in the 4 weeks preceding enrollment. | |

| Clinical stability | Absence of acute IBD flare requiring hospitalization, intravenous corticosteroids, or biologic induction within 4 weeks prior to study entry. |

| No significant changes in concomitant medications, diet, or lifestyle in the month prior to baseline sampling. | |

| Age and consent | Adults aged 18 to 65 years at the time of informed consent. |

| Ability and willingness to provide written informed consent and to comply with all digital monitoring, sample collection, and follow-up procedures. | |

| Technical and logistical feasibility | Access to a compatible smartphone or device required for app-based data collection (daily eDiary). |

| Agreement to provide serial stool and blood samples at baseline and 3-month follow-up. |

| Recent antimicrobial or probiotic use | Use of systemic or topical antibiotics (oral, intravenous, or intramuscular) within 30 days before baseline sample collection. |

| Use of antifungal agents, antiparasitic drugs, or non-standard antimicrobial supplements within the same period. | |

| Use of non-study probiotics or prebiotics initiated within 4 weeks prior to baseline. | |

| Acute or severe medical conditions | Active gastrointestinal infections (e.g., Clostridium difficile, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Giardia lamblia) |

| Known intestinal obstruction, perforation, or intra-abdominal abscess. | |

| Active gastrointestinal bleeding requiring medical intervention. | |

| Known colorectal carcinoma, dysplasia, or high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. | |

| Systemic or autoimmune disorders | Concurrent autoimmune diseases (e.g., lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis) that may confound immunologic or inflammatory endpoints. |

| Severe hepatic impairment (AST/ALT > 3× upper limit of normal) [63], renal failure (eGFR < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2) [64], or uncontrolled endocrine/metabolic disorders. | |

| Medication and immunosuppression | Current or recent use (within 3 months) of cytotoxic chemotherapy, immunosuppressive agents unrelated to IBD management, or systemic corticosteroids > 20 mg/day of prednisone equivalent. |

| Participation in another interventional clinical trial within 12 weeks prior to enrolment. | |

| Pregnancy and reproductive health | Pregnant or breastfeeding women, or those planning pregnancy during the study period. |

| Women of childbearing potential not willing to use adequate contraception during the study (barrier, hormonal, or intrauterine methods). | |

| Allergies and contraindications | Known hypersensitivity or allergy to any potential study component (nutritional supplements, probiotics, antimicrobial agents, or excipients). |

| Psychiatric or cognitive limitations | Cognitive impairment, psychiatric illness, or substance abuse that may interfere with the ability to consent or adhere to the study protocol. |

| Compliance and data integrity | Failure to complete baseline data entry, or anticipated inability to adhere to digital monitoring and follow-up visits. |

| Any condition deemed by the investigator to compromise patient safety or data reliability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lupusoru, R.; Moleriu, L.C.; Mare, R.; Sporea, I.; Popescu, A.; Sirli, R.; Goldis, A.; Nica, C.; Moga, T.V.; Miutescu, B.; et al. AI-Guided Multi-Omic Microbiome Modulation Improves Clinical and Inflammatory Outcomes in Refractory IDB: A Real-World Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010201

Lupusoru R, Moleriu LC, Mare R, Sporea I, Popescu A, Sirli R, Goldis A, Nica C, Moga TV, Miutescu B, et al. AI-Guided Multi-Omic Microbiome Modulation Improves Clinical and Inflammatory Outcomes in Refractory IDB: A Real-World Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):201. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010201

Chicago/Turabian StyleLupusoru, Raluca, Lavinia Cristina Moleriu, Ruxandra Mare, Ioan Sporea, Alina Popescu, Roxana Sirli, Adrian Goldis, Camelia Nica, Tudor Voicu Moga, Bogdan Miutescu, and et al. 2026. "AI-Guided Multi-Omic Microbiome Modulation Improves Clinical and Inflammatory Outcomes in Refractory IDB: A Real-World Study" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010201

APA StyleLupusoru, R., Moleriu, L. C., Mare, R., Sporea, I., Popescu, A., Sirli, R., Goldis, A., Nica, C., Moga, T. V., Miutescu, B., Ratiu, I., Belei, O., Olariu, L., Dumitrascu, V., & Dragomir, R. D. (2026). AI-Guided Multi-Omic Microbiome Modulation Improves Clinical and Inflammatory Outcomes in Refractory IDB: A Real-World Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010201