Cysteine Attenuates Intestinal Inflammation by Regulating the Gut Microbiota and TLR4-JNK/MAPK-NF-κB Pathway in Piglets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

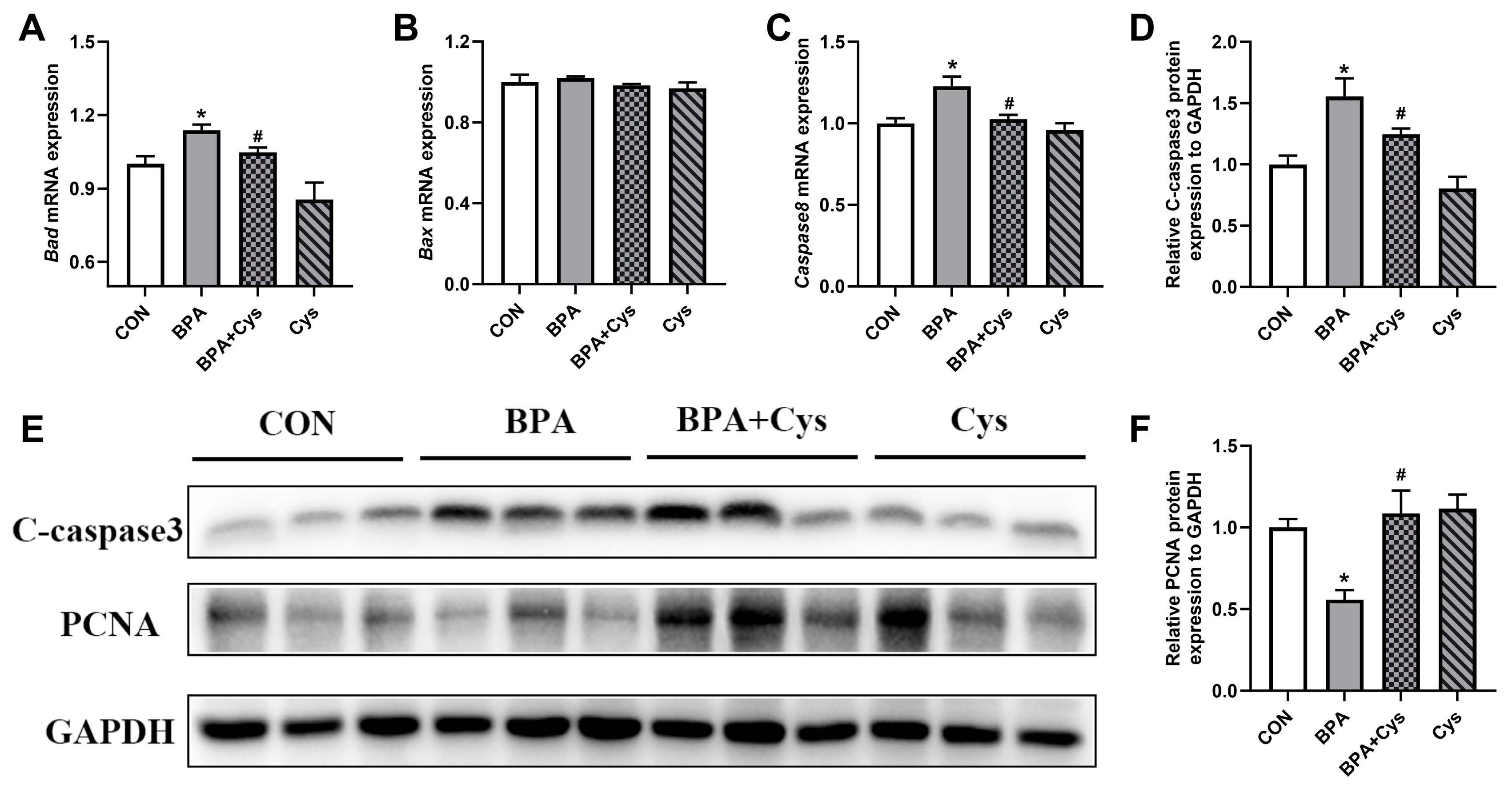

2.1. Jejunal Mucosal Cell Renewal

2.2. Jejunal Goblet Cell Distribution

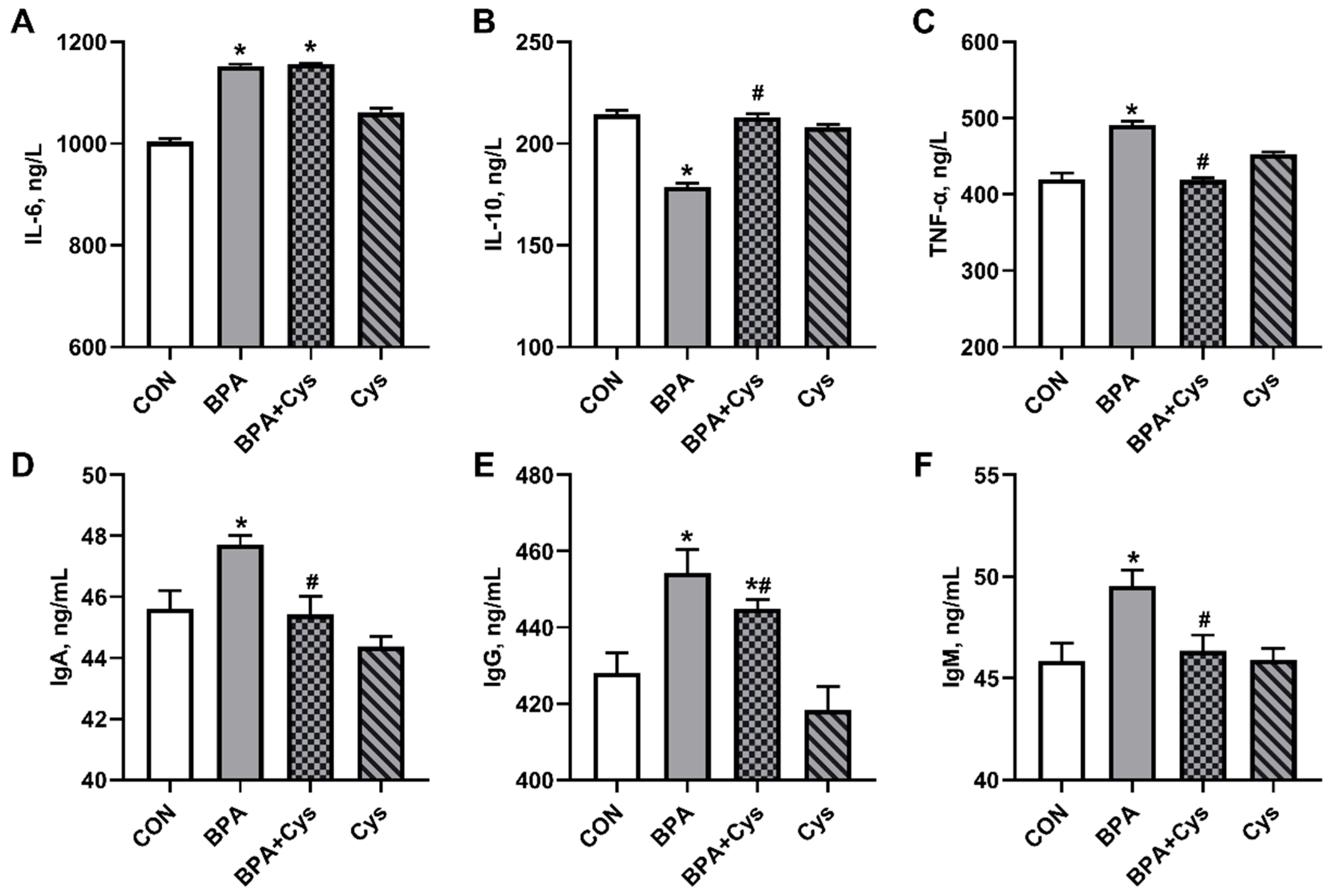

2.3. Serum Inflammatory Factors and Immunoglobulin Content

2.4. Jejunal Mucosa Inflammatory Factor and Immunoglobulin Contents

2.5. Jejunal Inflammation-Related Index Expression

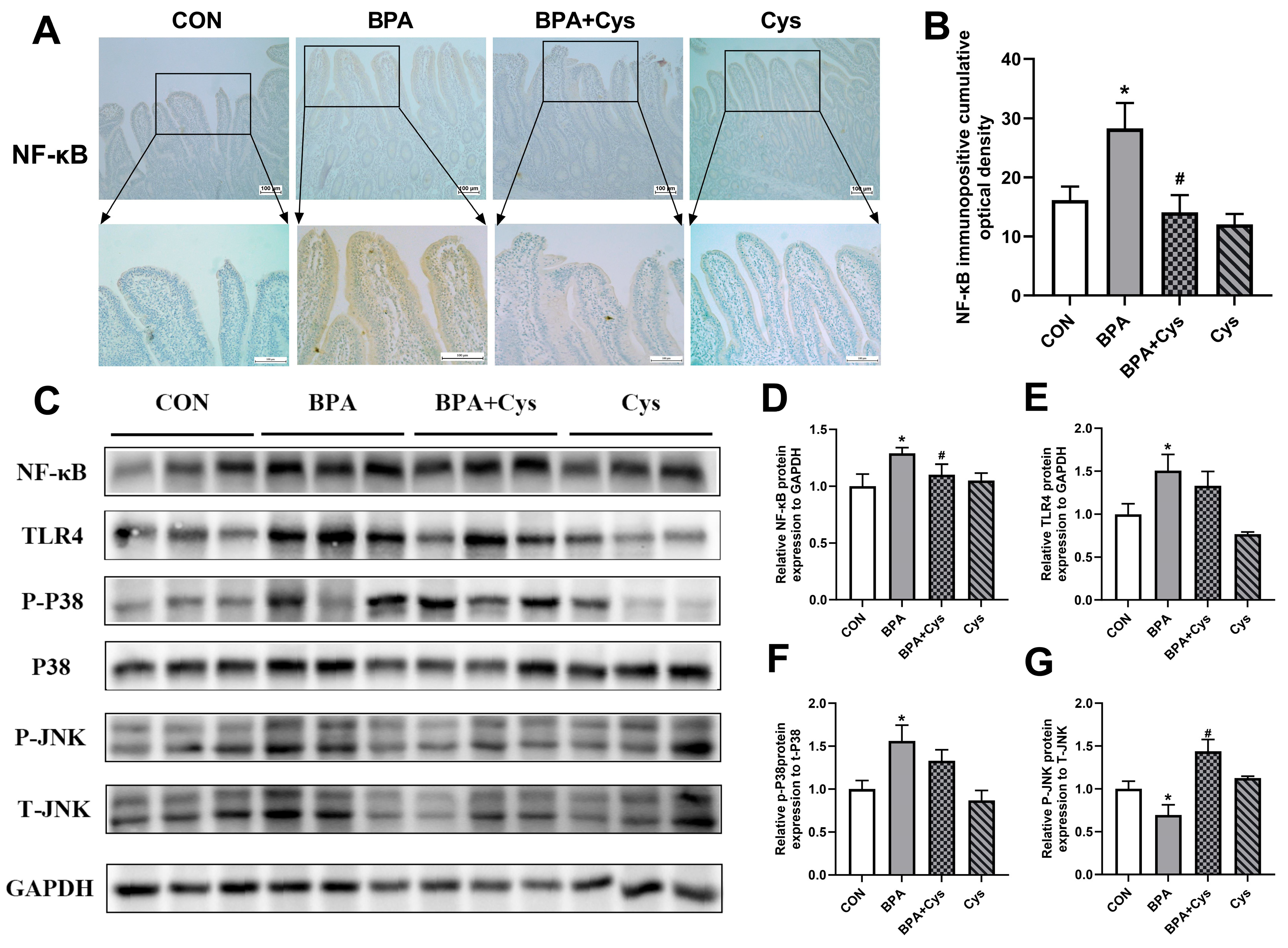

2.6. Cysteine Attenuated the Induction of NF-κB, TLR4 and p-p38 in BPA-Challenged Piglet Jejunum

2.7. Concentration of SCFAs in Cecal Content

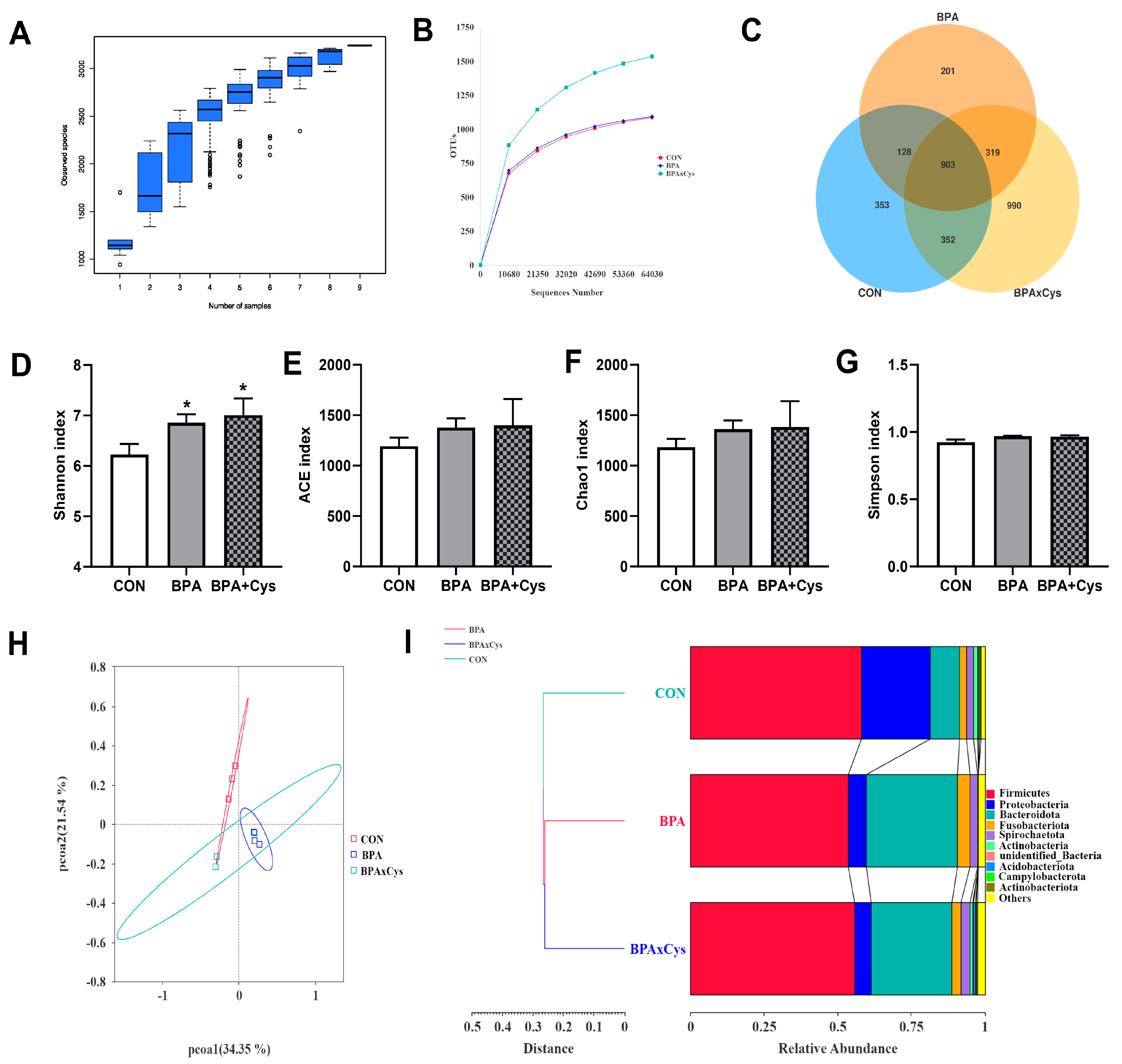

2.8. Diversity of Gut Microbiota

2.9. Abundance of Microbiota in the Cecal Content

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Experimental Design

4.2. Sample Collection

4.3. Determination of Inflammatory Factors and Immunoglobulin Contents

4.4. Identification and Detection of Goblet Cells

4.5. Immunohistochemistry Analysis

4.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

4.7. Western Blot Analysis

4.8. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Concentration in Cecum Content

4.9. Intestinal Microbial Diversity Analysis

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Bad | B-Cell Lymphoma-2 associated death promoter |

| Bax | B-Cell Lymphoma-2 associated X |

| BPA | Bisphenol A |

| Cys | Cysteine |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-γ |

| IgA | Immunoglobulin A |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| IgM | Immunoglobulin M |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| MyD88 | Myeloid differentiation factor 88 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-B |

| PCNA | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acid |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

References

- Beumer, J.; Clevers, H. Cell fate specification and differentiation in the adult mammalian intestine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, F.; Odle, J.; Lin, X.; Jacobi, S.K.; Zhu, H.; Wu, Z.; Hou, Y. Fish Oil Enhances Intestinal Integrity and Inhibits TLR4 and NOD2 Signaling Pathways in Weaned Pigs after LPS Challenge3. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 2017–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, K.; Yu, C.; Wang, L.; Liang, T.; Zhu, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y. Xylooligosaccharide attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced intestinal injury in piglets via suppressing inflammation and modulating cecal microbial communities. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhan, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhuo, Y.; Lin, Y.; Fang, Z.; Che, L.; Feng, B.; et al. Effects of a Diet Supplemented with Exogenous Catalase from Penicillium notatum on Intestinal Development and Microbiota in Weaned Piglets. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto-Hill, S.; Alenghat, T. Inflammation-Associated Microbiota Composition Across Domestic Animals. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 649599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Qin, P.; Di, Y.; Jiang, S.; Li, Y.; Huang, L.; Jiao, N.; Yang, W. Glutamine attenuates bisphenol A-induced intestinal inflammation by regulating gut microbiota and TLR4-p38/MAPK-NF-κB pathway in piglets. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 270, 115836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanska, K.; Makowska, K.; Gonkowski, S. The Influence of High and Low Doses of Bisphenol A (BPA) on the Enteric Nervous System of the Porcine Ileum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ren, W.; Yang, G.; Duan, J.; Huang, X.; Fang, R.; Li, C.; Li, T.; Yin, Y.; Hou, Y.; et al. L-Cysteine metabolism and its nutritional implications. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauchart-Thevret, C.; Cottrell, J.; Stoll, B.; Burrin, D.G. First-pass splanchnic metabolism of dietary cysteine in weanling pigs1. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 4093–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oz, H.S.; Chen, T.S.; Nagasawa, H. Comparative efficacies of 2 cysteine prodrugs and a glutathione delivery agent in a colitis model. Transl. Res. 2007, 150, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, N.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D.; Zhang, X.; Yin, J. Cysteine Exerts an Essential Role in Maintaining Intestinal Integrity and Function Independent of Glutathione. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, 2100728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, P.; Ma, S.; Li, C.; Di, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Jiang, S.; Yang, W.; Jiao, N. Cysteine Attenuates the Impact of Bisphenol A-Induced Oxidative Damage on Growth Performance and Intestinal Function in Piglets. Toxics 2023, 11, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braniste, V.; Jouault, A.; Gaultier, E.; Polizzi, A.; Buisson-Brenac, C.; Leveque, M.; Martin, P.G.; Theodorou, V.; Fioramonti, J.; Houdeau, E. Impact of oral bisphenol A at reference doses on intestinal barrier function and sex differences after perinatal exposure in rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.-P.; Chung, Y.-T.; Li, R.; Wan, H.-T.; Wong, C.K.-C. Bisphenol A alters gut microbiome: Comparative metagenomics analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, D.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Che, L.; Fang, Z.; Xu, S.; Lin, Y.; Feng, B.; Li, J.; et al. Maternal methyl donor supplementation during gestation counteracts bisphenol A–induced oxidative stress in sows and offspring. Nutrition 2018, 45, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, F.; Wen, D.; Mu, R. Exposure to bisphenol A induced oxidative stress, cell death and impaired epithelial homeostasis in the adult Drosophila melanogaster midgut. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 248, 114285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Liang, S.; Zan, G.; Wang, X.; Gao, C.; Yan, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J. Selenomethionine Alleviates DON-Induced Oxidative Stress via Modulating Keap1/Nrf2 Signaling in the Small Intestinal Epithelium. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.J.; Kovacs-Nolan, J.; Yang, C.; Archbold, T.; Fan, M.Z.; Mine, Y. L-cysteine supplementation attenuates local inflammation and restores gut homeostasis in a porcine model of colitis. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2009, 1790, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Qiu, L.; Zhu, J.; Sun, Q.; Qu, W.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, Y.; Shao, G. Environmental contaminant BPA causes intestinal damage by disrupting cellular repair and injury homeostasis in vivo and in vitro. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.H.; Tong, G.; Xiao, K.; Jiao, L.F.; Ke, Y.L.; Hu, C.H. L-Cysteine protects intestinal integrity, attenuates intestinal inflammation and oxidant stress, and modulates NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways in weaned piglets after LPS challenge. Innate Immun. 2016, 22, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Cai, X.; Guo, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhu, S.; Xu, J. Effect of N-acetyl cysteine on enterocyte apoptosis and intracellular signalling pathways’ response to oxidative stress in weaned piglets. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 1938–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziani, F.; Pinton, P.; Olleik, H.; Pujol, A.; Nicoletti, C.; Sicre, M.; Quinson, N.; Ajandouz, E.H.; Perrier, J.; Pasquale, E.D.; et al. Deoxynivalenol inhibits the expression of trefoil factors (TFF) by intestinal human and porcine goblet cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Jacobson, A.; Meerschaert, K.A.; Sifakis, J.J.; Wu, M.; Chen, X.; Yang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Anekal, P.V.; Rucker, R.A.; et al. Nociceptor neurons direct goblet cells via a CGRP-RAMP1 axis to drive mucus production and gut barrier protection. Cell 2022, 185, 4190–4205.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnason, I.; Macpherson, A.; Hollander, D. Intestinal permeability: An overview. Gastroenterology 1995, 108, 1566–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermiston, M.L.; Gordon, J.I. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Adenomas in Mice Expressing a Dominant Negative N-Cadherin. Science 1995, 270, 1203–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, C.; Perillo, F.; Strati, F.; Fantini, M.; Caprioli, F.; Facciotti, F. The Role of Gut Microbiota Biomodulators on Mucosal Immunity and Intestinal Inflammation. Cells 2020, 9, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, T.; Hammarström, L.; Zhao, Y. The Immunoglobulins: New Insights, Implications, and Applications. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2020, 8, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zusso, M.; Lunardi, V.; Franceschini, D.; Pagetta, A.; Lo, R.; Stifani, S.; Frigo, A.C.; Giusti, P.; Moro, S. Ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin attenuate microglia inflammatory response via TLR4/NF-kB pathway. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.-W.; More, S.V.; Yun, Y.-S.; Ko, H.-M.; Kwak, J.-H.; Lee, H.; Suk, K.; Kim, I.-S.; Choi, D.-K. A novel synthetic compound MCAP suppresses LPS-induced murine microglial activation in vitro via inhibiting NF-kB and p38 MAPK pathways. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2016, 37, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lim, K.-T. Expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in HMC-1 cells treated with bisphenol A is attenuated by plant-originating glycoprotein (75 kDa) by blocking p38 MAPK. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2010, 382, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, N.; Xu, D.; Qiu, K.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Piao, X.; Yin, J. Restoring mitochondrial function and normalizing ROS-JNK/MAPK pathway exert key roles in glutamine ameliorating bisphenol a-induced intestinal injury. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 7442–7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gresse, R.; Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Fleury, M.A.; Van De Wiele, T.; Forano, E.; Blanquet-Diot, S. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Postweaning Piglets: Understanding the Keys to Health. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 851–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, R.; Li, S.; Diao, H.; Huang, C.; Yan, J.; Wei, X.; Zhou, M.; He, P.; Wang, T.; Fu, H.; et al. The interaction between dietary fiber and gut microbiota, and its effect on pig intestinal health. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1095740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, K.; Ali, M.; D’Souza, M.; Hughes, P.D.; Sulakhe, D.; Wang, A.Z.; Xie, B.; Yeasin, R.; Msall, M.E.; Andrews, B.; et al. Bacteroidota and Lachnospiraceae integration into the gut microbiome at key time points in early life are linked to infant neurodevelopment. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1997560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinav, E.; Strowig, T.; Kau, A.L.; Henao-Mejia, J.; Thaiss, C.A.; Booth, C.J.; Peaper, D.R.; Bertin, J.; Eisenbarth, S.C.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. NLRP6 Inflammasome Regulates Colonic Microbial Ecology and Risk for Colitis. Cell 2011, 145, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.P.; Rosendale, D.I.; Roberton, A.M. Prevotella enzymes involved in mucin oligosaccharide degradation and evidence for a small operon of genes expressed during growth on mucin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 190, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, J.; Hornung, B.; Renckens, B.; Van Hijum, S.A.F.T.; Martins Dos Santos, V.A.P.; Rijkers, G.T.; Schaap, P.J.; De Vos, W.M.; Smidt, H. Genomic and functional analysis of Romboutsia ilealis CRIBT reveals adaptation to the small intestine. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangifesta, M.; Mancabelli, L.; Milani, C.; Gaiani, F.; de’Angelis, N.; de’Angelis, G.L.; Van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M.; Turroni, F. Mucosal microbiota of intestinal polyps reveals putative biomarkers of colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Ma, L.; Li, Z.; Yin, J.; Tan, B.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Q.; Ma, X. Evolution of the Gut Microbiota and Its Fermentation Characteristics of Ningxiang Pigs at the Young Stage. Animals 2021, 11, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Yuan, H.; Wachemo, A.C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Wen, H.; Wang, J.; Li, X. The relationships among sCOD, VFAs, microbial community, and biogas production during anaerobic digestion of rice straw pretreated with ammonia. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, V.; Pozuelo, M.; Borruel, N.; Casellas, F.; Campos, D.; Santiago, A.; Martinez, X.; Varela, E.; Sarrabayrouse, G.; Machiels, K.; et al. A microbial signature for Crohn’s disease. Gut 2017, 66, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Li, D.; Yang, X. Gut metabolomics and 16S rRNA sequencing analysis of the effects of arecoline on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1132026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, Z.; Zhang, M.; Fu, B.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Fang, X.; Li, Z.; Teng, T.; Shi, B. Branched short-chain fatty acid-rich fermented protein food improves the growth and intestinal health by regulating gut microbiota and metabolites in young pigs. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 21594–21609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glöckner, F.O.; Yilmaz, P.; Quast, C.; Gerken, J.; Beccati, A.; Ciuprina, A.; Bruns, G.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Westram, R.; et al. 25 years of serving the community with ribosomal RNA gene reference databases and tools. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 261, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Accession No. | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | F: TTGTCTGTGATGCCAACGTG | XM_021085847.1 | 108 |

| R: TGAGGAGGTGGAGAGCCTTC | |||

| IL-4 | F: GCTTCGGCACATCTACAGACACC | NM_214123.1 | 110 |

| R: TCTTGGCTTCATGCACAGAACAGG | |||

| IL-6 | F: ACCGGTCTTGTGGAGTTTCA | NM_001252429.1 | 170 |

| R: GCATTTGTGGTGGGGTTAGG | |||

| TNF-α | F: CCAATGGCAGAGTGGGTATG | JF831365.1 | 116 |

| R: TGAAGAGGACCTGGGAGTAG | |||

| IL-10 | F: AACCACAAGTCCGACTCAACGAAG | NM_214041.1 | 81 |

| R: GCCAGGAAGATCAGGCAATAGAGC | |||

| TLR4 | F: CTCCAGCTTTCCAGAACTGC | NM_001113039.2 | 192 |

| R: AGGTTTGTCTCAACGGCAAC | |||

| NF-κB | F: CTCGCACAAGGAGACATGAA | NM_001048232.1 | 147 |

| R: TGAAGAGGACCTGGGAGTAG | |||

| MyD88 | F: ATTGAAAAGAGGTGCCGTCG | NM_001099923.1 | 188 |

| R: CAGACAGTGATGAACCGCAG | |||

| IFN-γ | F:AGCTTTGCGTGACTTTGTGT | NM_213948.1 | 247 |

| R:ATGCTCCTTTGAATGGCCTG | |||

| β-Actin | F: CCACGAAACTACCTTCAACTC | NM_001170517.2 | 131 |

| R: TGATCTCCTTCTGCATCCTGT |

| Antibodies | Catalog No. | Source | Dilution | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCNA | bs-2006R | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Bioss, Beijing, China |

| Cleaved Caspase-3 (Asp175) | #9661 | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| SAPK/JNK | #9252 | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| Phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) (81E11) | #4668 | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| NF-κB p65 (D14E12) | #8242 | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| Toll-like Receptor 4 (D8L5W) | #14358 | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| p38/MAPK | #8690 | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| Phospho-p38/MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) | #4511 | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| GAPDH | HX1832 | Rabbit | 1:5000 | Huaxingbio, Beijing, China |

| Anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) | A0208 | 1:3000 | Beyotime, Shanghai, China |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, R.; Qin, P.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.; Jiang, S.; Yuan, X.; Yang, W.; Huang, C.; Jiao, N. Cysteine Attenuates Intestinal Inflammation by Regulating the Gut Microbiota and TLR4-JNK/MAPK-NF-κB Pathway in Piglets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411991

Liu R, Qin P, Liu Z, Liu W, Jiang S, Yuan X, Yang W, Huang C, Jiao N. Cysteine Attenuates Intestinal Inflammation by Regulating the Gut Microbiota and TLR4-JNK/MAPK-NF-κB Pathway in Piglets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411991

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Rui, Pengxiang Qin, Zihao Liu, Wenjing Liu, Shuzhen Jiang, Xuejun Yuan, Weiren Yang, Caiyun Huang, and Ning Jiao. 2025. "Cysteine Attenuates Intestinal Inflammation by Regulating the Gut Microbiota and TLR4-JNK/MAPK-NF-κB Pathway in Piglets" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411991

APA StyleLiu, R., Qin, P., Liu, Z., Liu, W., Jiang, S., Yuan, X., Yang, W., Huang, C., & Jiao, N. (2025). Cysteine Attenuates Intestinal Inflammation by Regulating the Gut Microbiota and TLR4-JNK/MAPK-NF-κB Pathway in Piglets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411991