Metabolomic Profiling of Middle Ear Effusion Suggests a Predominant Influence of Age over Viscosity: An HR-MAS NMR Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

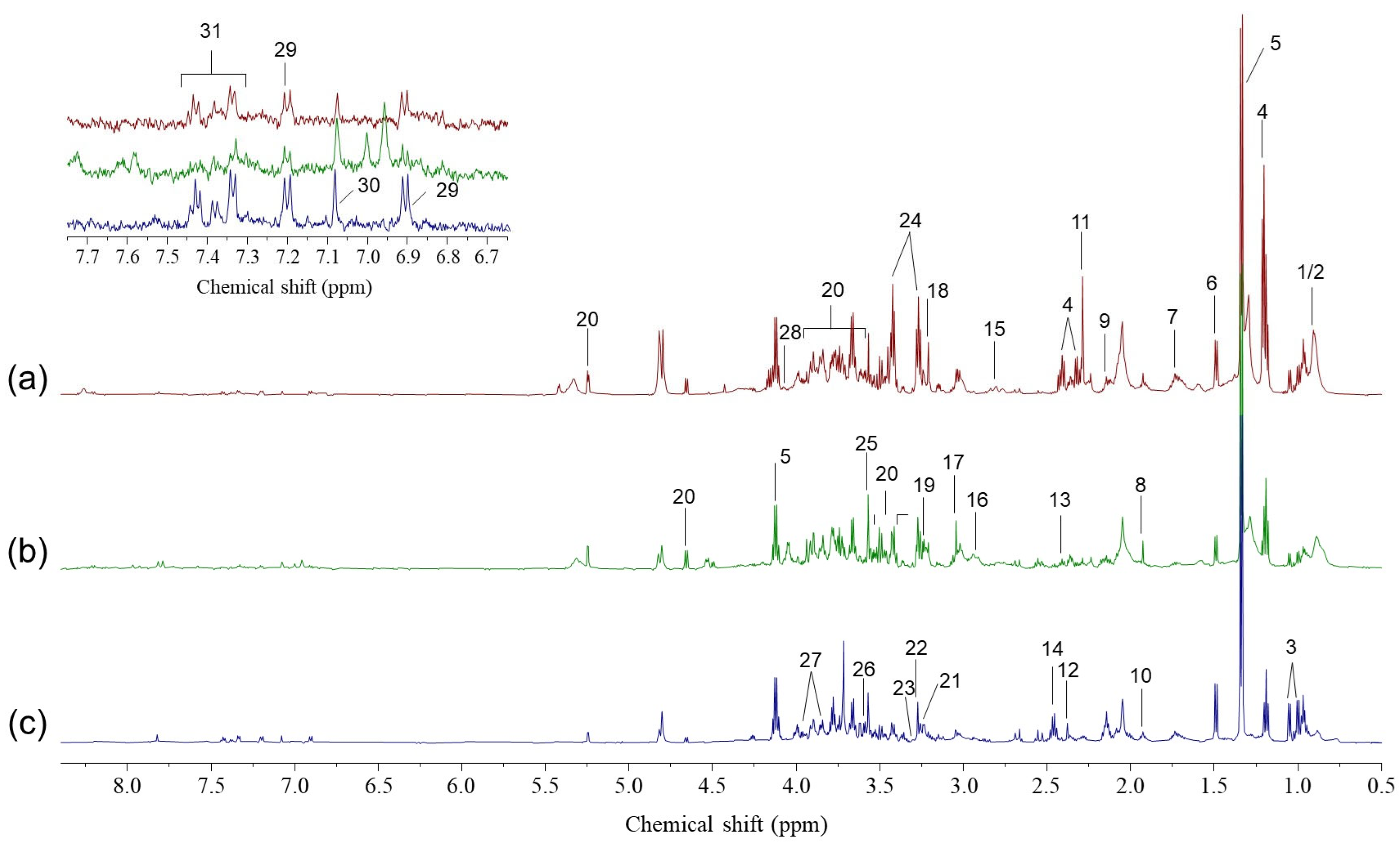

2.1. Global Metabolomic Profiling of Middle Ear Effusions

2.2. Differential Metabolites Identified Among Effusion Groups

2.3. Age-Dependent Metabolic Variations Dominate the MEE Profile

2.4. Identification of Viscosity Type-Dependent Metabolites After Adjusting for Age

2.5. Discriminatory Performance of Viscosity-Specific Biomarkers

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population, Sample Collection, and Classification

4.2. HR-MAS NMR Spectroscopy

4.3. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAUC | Age-adjusted area under the curve |

| Ala | Alanine |

| ANCOVA | Analysis of covariance |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| Arg | Arginine |

| AROC | Covariate-adjusted receiver operating characteristic |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| Cys | Cysteine |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| Gln | Glutamine |

| Glu | Glutamate |

| GLM/glm | Generalized linear model |

| Gly | Glycine |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| His | Histidine |

| HR-MAS | High-resolution magic-angle spinning |

| HR-MAS NMR | High-resolution magic-angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance |

| Ile | Isoleucine |

| IRB | Institutional review board |

| Lac | Lactate |

| Leu | Leucine |

| Lys | Lysine |

| MC | Mucous_Child group |

| MEE | Middle ear effusion |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| MUC5B | Mucin 5B |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| OME | Otitis media with effusion |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| Pro | Proline |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| SA | Serous_Adult group |

| SC | Serous_Child group |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| Ser | Serine |

| Tau | Taurine |

| Val | Valine |

References

- Rosenfeld, R.M.; Shin, J.J.; Schwartz, S.R.; Coggins, R.; Gagnon, L.; Hackell, J.M.; Hoelting, D.; Hunter, L.L.; Kummer, A.W.; Payne, S.C.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline. Clinical practice guideline: Otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 154, S1–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, P.; Page, C. Otitis media with effusion in children: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. A review. J. Otol. 2019, 14, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilder, A.G.; Chonmaitree, T.; Cripps, A.W.; Rosenfeld, R.M.; Casselbrant, M.L.; Haggard, M.P.; Venekamp, R.P. Otitis media. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Wan, G.; Sun, J.; Sun, J.; Zhao, W. Incidence and characteristics of otitis media with effusion in adults before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 2275–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duah, V.; Huang, Z.; Val, S.; DeMason, C.; Poley, M.; Preciado, D. Younger patients with COME are more likely to have mucoid middle ear fluid containing mucin MUC5B. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 90, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, T.L.; Yan, J.C.; Khampang, P.; Dettmar, P.W.; MacKinnon, A.; Hong, W.; Johnston, N.; Papsin, B.C.; Chun, R.H.; McCormick, M.E.; et al. Association of Gel-Forming Mucins and Aquaporin Gene Expression with HEARing Loss, Effusion Viscosity, and Inflammation in otitis media with effusion. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 143, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, M.H.; Cho, Y.S.; Choi, J.; Choung, Y.H.; Chung, J.H.; Chung, J.W.; Han, G.C.; Jun, B.C.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, K.S.; et al. Factors affecting the extrusion rate and complications after ventilation tube insertion: A multicenter registry study on the effectiveness of ventilation tube insertion in pediatric patients with chronic otitis media with effusion—Part II. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 15, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Val, S.; Poley, M.; Anna, K.; Nino, G.; Brown, K.; Pérez-Losada, M.; Gordish-Dressman, H.; Preciado, D. Characterization of mucoid and serous middle ear effusions from patients with chronic otitis media: Implication of different biological mechanisms? Pediatr. Res. 2018, 84, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutta, M.F.; Lambie, J.; Hobson, L.; Williams, D.; Tyrer, H.E.; Nicholson, G.; Brown, S.D.M.; Brown, H.; Piccinelli, C.; Devailly, G.; et al. Transcript analysis reveals a hypoxic inflammatory environment in human chronic otitis media with effusion. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, W.S.; Kim, H.N.; Yoon, J.H. Compositional difference in middle ear effusion: Mucous versus serous. Laryngoscope 2002, 112, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.; Hathorn, I. Aetiology and pathology of otitis media with effusion in adult life. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2016, 130, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coticchia, J.M.; Chen, M.; Sachdeva, L.; Mutchnick, S. New paradigms in the pathogenesis of otitis media in children. Front. Pediatr. 2013, 1, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, G.J.; Yanes, O.; Siuzdak, G. Innovation: Metabolomics: The apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.H.; Ivanisevic, J.; Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics: Beyond biomarkers and towards mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, H.; Courtier-Murias, D.; Soong, R.; Bermel, W.; Kingery, W.; Simpson, A. HR-MAS NMR spectroscopy: A practical guide for natural samples. Curr. Org. Chem. 2013, 17, 3013–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, J.D.; Enerbäck, S. Lactate: The ugly duckling of energy metabolism. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, L.R.; Tompkins, S.C.; Taylor, E.B. Regulation of pyruvate metabolism and human disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 2577–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, F.; Ma, Y.; Ai, R.; Ding, Z.; Li, D.; Zhu, Y.; He, Q.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Y.; He, Y. Glycolytic metabolism is critical for the innate antibacterial defense in acute Streptococcus pneumoniae otitis media. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 624775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsson-McDermott, E.M.; O’Neill, L.A. The Warburg effect then and now: From cancer to inflammatory diseases. BioEssays 2013, 35, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Heredero, G.; Gómez de Las Heras, M.M.; Gabandé-Rodríguez, E.; Oller, J.; Mittelbrunn, M. Glycolysis—A key player in the inflammatory response. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 3350–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, S.E.; O’Neill, L.A. HIF1α and metabolic reprogramming in inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3699–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, K.M.; Tee, A.R. Leucine and mTORC1: A complex relationship. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 302, E1329–E1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Yin, Y.; Tan, B.; Kong, X.; Wu, G. Leucine nutrition in animals and humans: mTOR signaling and beyond. Amino Acids 2011, 41, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.D.; Pollizzi, K.N.; Heikamp, E.B.; Horton, M.R. Regulation of immune responses by mTOR. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Pearce, E.L. Amino assets: How amino acids support immunity. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsholme, P.; Procopio, J.; Lima, M.M.; Pithon-Curi, T.C.; Curi, R. Glutamine and glutamate—Their central role in cell metabolism and function. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2003, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Gollapalli, K.; Mangiola, S.; Schranner, D.; Yusuf, M.A.; Chamoli, M.; Shi, S.L.; Lopes Bastos, B.; Nair, T.; Riermeier, A.; et al. Taurine deficiency as a driver of aging. Science 2023, 380, eabn9257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripps, H.; Shen, W. Review: Taurine: A “very essential” amino acid. Mol. Vis. 2012, 18, 2673–2686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marcinkiewicz, J.; Kontny, E. Taurine and inflammatory diseases. Amino Acids 2014, 46, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, C.E.; Wheeler, K.M.; Ribbeck, K. Mucins and their role in shaping the functions of mucus barriers. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 34, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, S.; Takahashi, K.; Azuma, J. Role of osmoregulation in the actions of taurine. Amino Acids 2000, 19, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.H.; Kolarich, D.; Packer, N.H. Mucin-type O-glycosylation—Putting the pieces together. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geeraerts, S.L.; Heylen, E.; De Keersmaecker, K.; Kampen, K.R. The ins and outs of serine and glycine metabolism in cancer. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preciado, D.; Goyal, S.; Rahimi, M.; Watson, A.M.; Brown, K.J.; Hathout, Y.; Rose, M.C. MUC5B Is the predominant mucin glycoprotein in chronic otitis media fluid. Pediatr. Res. 2010, 68, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarrere, C.A.; Kassab, G.S. Glutathione: A Samsonian life-sustaining small molecule that protects against oxidative stress, ageing and damaging inflammation. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1007816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Veen, J.N.; Kennelly, J.P.; Wan, S.; Vance, J.E.; Vance, D.E.; Jacobs, R.L. The critical role of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine metabolism in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2017, 1859, 1558–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, C.; Fung, C.W.; Sanchez-Lopez, E. Choline in immunity: A key regulator of immune cell activation and function. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1617077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metabolites | ANOVA FDR | Significant Pairwise Comparisons (p < 0.05) | Spearman Correlation with Age in Serous Groups | Spearman FDR | ANCOVA FDR (Age-Adjusted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyruvate | 2.33 × 10−8 | SA—MC; SA—SC | 0.603 | 6.73 × 10−6 | 0.5735 |

| Glutamate | 1.06 × 10−6 | MC—SA; SC—SA | −0.433 | 0.0069 | 0.3204 |

| Glycine | 1.06 × 10−6 | MC—SA; MC—SC; SC—SA | −0.202 | 0.1879 | 0.0139 |

| Choline | 2.70 × 10−5 | MC—SA; MC—SC; SC—SA | −0.258 | 0.0981 | 0.0398 |

| Citrate | 3.01 × 10−5 | SA—MC; SA—SC | 0.157 | 0.3276 | 0.0422 |

| Lactate | 3.01 × 10−5 | SA—MC; SA—SC | 0.371 | 0.0164 | 0.251 |

| Taurine | 7.23 × 10−5 | MC—SA; MC—SC | −0.263 | 0.0981 | 0.0092 |

| Asparagine | 0.0002 | SA—MC; SA—SC | 0.394 | 0.0158 | 0.6381 |

| Cystine | 0.0002 | SA—MC; SA—SC | 0.303 | 0.0571 | 0.446 |

| Glutamine | 0.0003 | SA—MC; SA—SC | 0.254 | 0.0981 | 0.145 |

| Lysine | 0.0005 | MC—SA; SC—SA | −0.099 | 0.5524 | 0.0603 |

| Leucine | 0.0009 | MC—SA; SC—SA | −0.381 | 0.0164 | 0.3763 |

| Serine | 0.0009 | MC—SA | −0.216 | 0.1578 | 0.0888 |

| Glucose | 0.0015 | SA—MC; SA—SC | 0.306 | 0.0571 | 0.9772 |

| Betaine | 0.0018 | SA—MC; SA—SC | 0.365 | 0.0164 | 0.6033 |

| Succinate | 0.0019 | MC—SA; MC—SC | −0.253 | 0.0981 | 0.1155 |

| sn-Glycero-3-phosphocholine | 0.0116 | SA—MC; SA—SC | 0.071 | 0.6933 | 0.3037 |

| Characteristics | Adult | Child | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serous | Mucous | Serous | |

| Number of patients (n) | 45 | 21 | 17 |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 67.71 ± 13.24 (40–86) | 3.28 ± 1.90 (1–7) | 4.82 ± 3.10 (1–11) |

| Male:Female | 20:25 | 13:4 | 15:6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Moon, S.; Oh, S.-J.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, H.-M.; Kim, S.; Choi, S.-W. Metabolomic Profiling of Middle Ear Effusion Suggests a Predominant Influence of Age over Viscosity: An HR-MAS NMR Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010020

Lee S, Kim S, Moon S, Oh S-J, Kim S-H, Lee H-M, Kim S, Choi S-W. Metabolomic Profiling of Middle Ear Effusion Suggests a Predominant Influence of Age over Viscosity: An HR-MAS NMR Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seokhwan, Seonghye Kim, Sojeon Moon, Se-Joon Oh, Seok-Hyun Kim, Hyun-Min Lee, Suhkmann Kim, and Sung-Won Choi. 2026. "Metabolomic Profiling of Middle Ear Effusion Suggests a Predominant Influence of Age over Viscosity: An HR-MAS NMR Study" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010020

APA StyleLee, S., Kim, S., Moon, S., Oh, S.-J., Kim, S.-H., Lee, H.-M., Kim, S., & Choi, S.-W. (2026). Metabolomic Profiling of Middle Ear Effusion Suggests a Predominant Influence of Age over Viscosity: An HR-MAS NMR Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010020