Epigenetic Signatures of Social Defeat Stress Varying Duration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. 30 Days of SDS Causes More Pronounced Behavioral Disturbances Compared to 10 Days of SDS

2.2. SDS Alters Density of Nucleosome H3K4me3 Peaks Depending on the Stress Duration

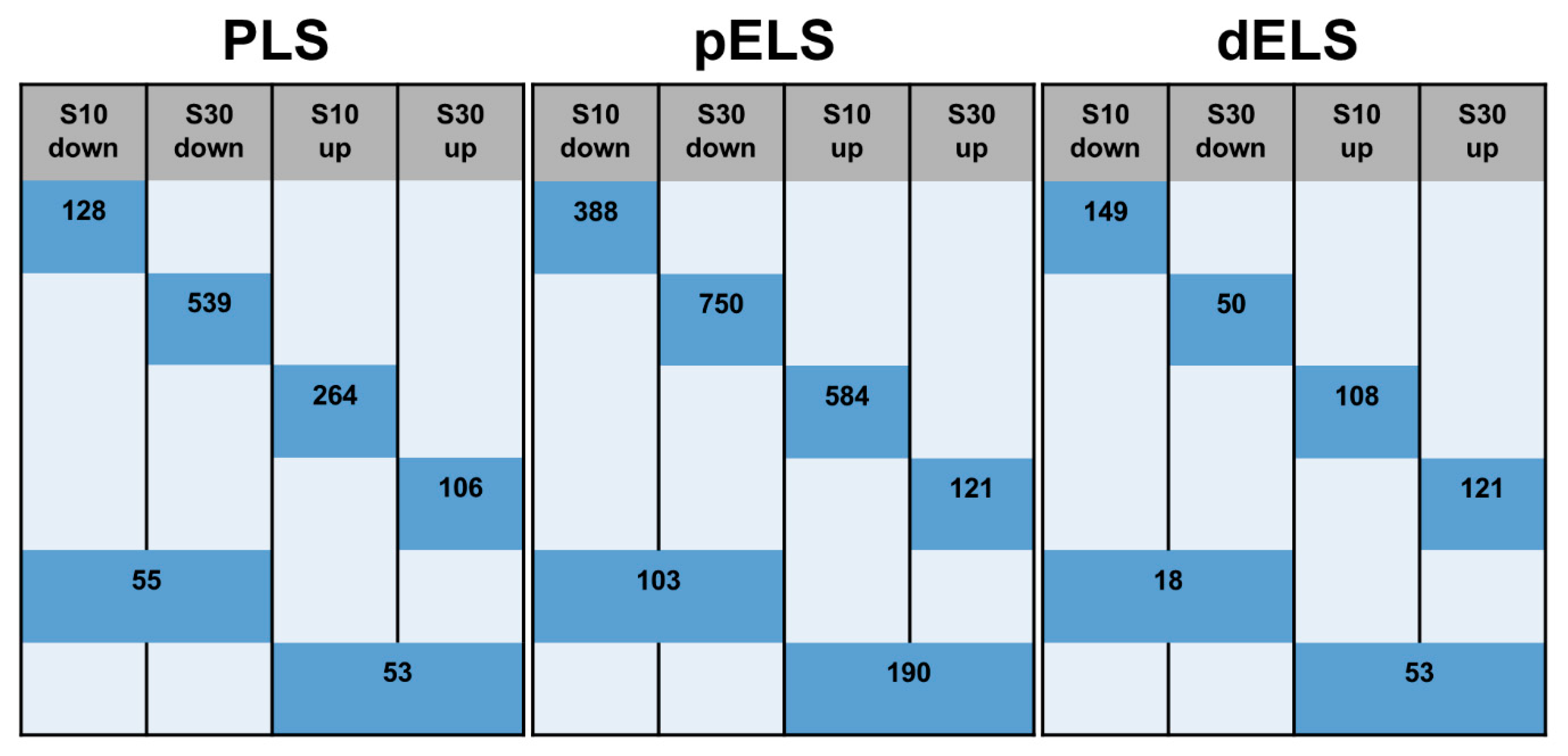

2.3. Distribution of Peaks Among cCRE Regulatory Elements

2.4. Gene Ontology Analysis Links Chromatin Dynamics to Specific Biological Processes Across Stress Durations

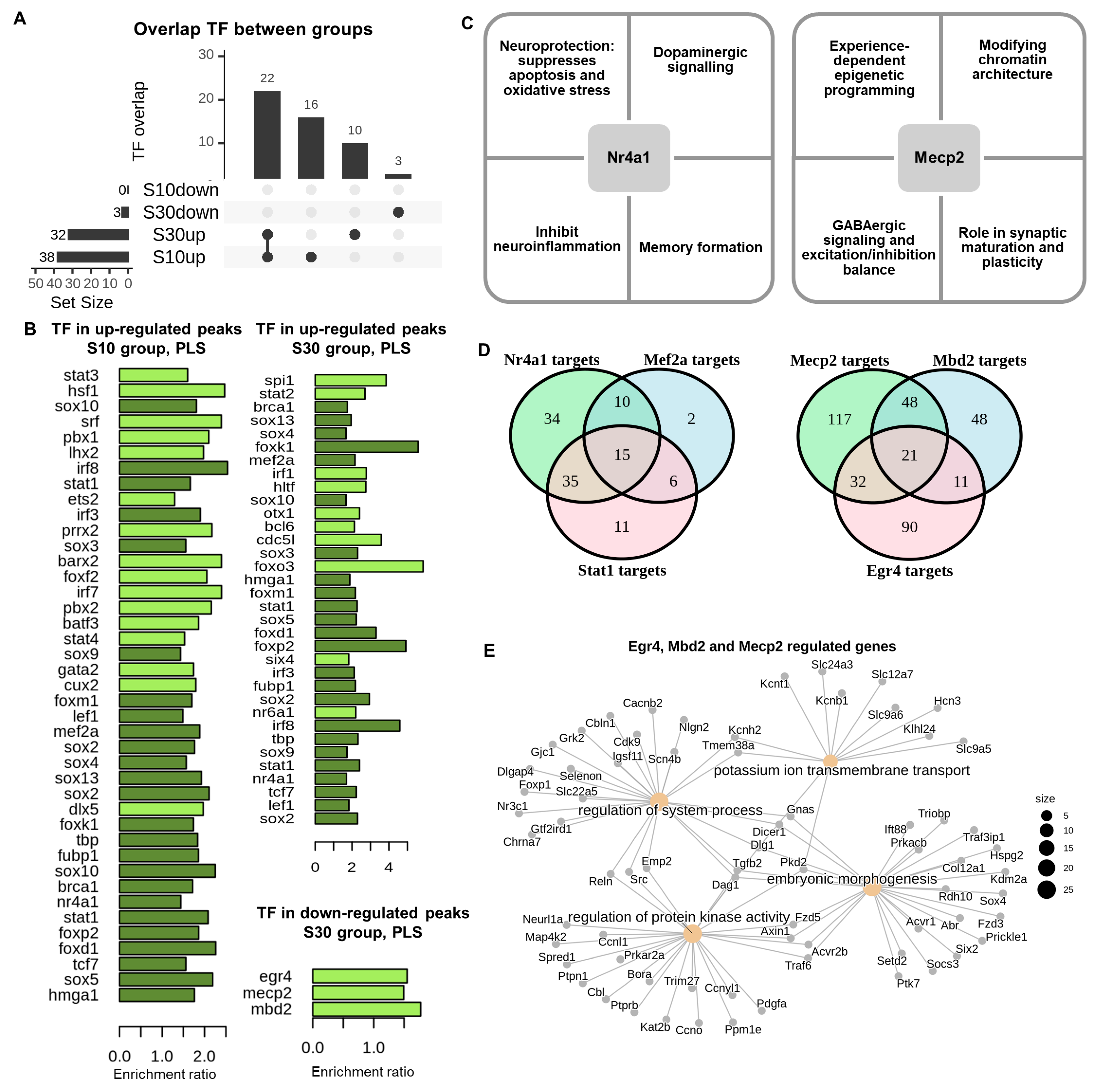

2.5. Motif Enrichment Analysis

2.6. The Aggregation of Numerous H3K4me3 Nucleosome Peaks in the Promoter Region Likely Delineates Distinct Signatures for Transcription Factor Accessibility and May Affect Expression Levels

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Animals

3.2. Experimental Design

3.3. Partition Test

3.4. Forced Swim Test

3.5. Evaluation of Behavioral Score

3.6. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation and Library Construction

3.7. Analysis of ChIP-seq Data

3.8. Motif Enrichment Analysis

3.9. GO Enrichment Analysis

3.10. Using Public Available RNA-seq and ChIP-seq Data

3.11. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDS | Social defeat stress |

| FST | Forced Swim Test |

| cCREs | Cis-regulatory elements |

| PLSs | Promoter-like signatures |

| pELS | Proximal enhancer-like signatures |

| dELSs | Distal enhancer-like signatures |

| DE | Differential enrichment |

| TSS | Transcription start site |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| PFC | Prefrontal cortex |

References

- Zorn, J.V.; Schür, R.R.; Boks, M.P.; Kahn, R.S.; Joëls, M.; Vinkers, C.H. Cortisol Stress Reactivity across Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 77, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Estrela, C.; McGrath, J.; Booij, L.; Gouin, J.-P. Heart Rate Variability, Sleep Quality, and Depression in the Context of Chronic Stress. Ann. Behav. Med. 2021, 55, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, S.; Magnavita, N. Work Stress and Metabolic Syndrome in Police Officers. A Prospective Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, N.; Ballegaard, S.; Krogh, J.; Bech, P.; Hjalmarson, Å.; Gyntelberg, F.; Faber, J. Chronic Psychological Stress Seems Associated with Elements of the Metabolic Syndrome in Patients with Ischaemic Heart Disease. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2017, 77, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbidi, S.; Frisbee, J.C.; Laher, I. Chronic Stress Impacts the Cardiovascular System: Animal Models and Clinical Outcomes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015, 308, H1476–H1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, B.; Meng, L.; Hao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, T.; Guo, Z. Chronic Stress: A Critical Risk Factor for Atherosclerosis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 1429–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallensten, J.; Ljunggren, G.; Nager, A.; Wachtler, C.; Bogdanovic, N.; Petrovic, P.; Carlsson, A.C. Stress, Depression, and Risk of Dementia—A Cohort Study in the Total Population between 18 and 65 Years Old in Region Stockholm. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2023, 15, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Neurobiological and Systemic Effects of Chronic Stress. Chronic Stress 2017, 1, 2470547017692328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirven, B.C.J.; Homberg, J.R.; Kozicz, T.; Henckens, M.J.A.G. Epigenetic Programming of the Neuroendocrine Stress Response by Adult Life Stress. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2017, 59, R11–R31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururajan, A.; Reif, A.; Cryan, J.F.; Slattery, D.A. The Future of Rodent Models in Depression Research. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 686–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venzala, E.; García-García, A.L.; Elizalde, N.; Delagrange, P.; Tordera, R.M. Chronic Social Defeat Stress Model: Behavioral Features, Antidepressant Action, and Interaction with Biological Risk Factors. Psychopharmacology 2012, 224, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reshetnikov, V.V.; Kisaretova, P.E.; Bondar, N.P. Transcriptome Alterations Caused by Social Defeat Stress of Various Durations in Mice and Its Relevance to Depression and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Humans: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururajan, A. The Impact of Chronic Stress on the PFC Transcriptome: A Bioinformatic Meta-Analysis of Publicly Available RNA-Sequencing Datasets. Stress 2022, 25, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Hagenauer, M.H.; Rhoads, C.A.; Flandreau, E.; Rempel-Clower, N.; Hernandez, E.; Nguyen, D.M.; Saffron, A.; Duan, T.; Watson, S.; et al. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Chronic Stress on the Prefrontal Transcriptome in Animal Models and Convergence with Existing Human Data. bioRxiv, 2025; preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Reshetnikov, V.V.; Kisaretova, P.E.; Ershov, N.I.; Merkulova, T.I.; Bondar, N.P. Social Defeat Stress in Adult Mice Causes Alterations in Gene Expression, Alternative Splicing, and the Epigenetic Landscape of H3K4me3 in the Prefrontal Cortex: An Impact of Early-Life Stress. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 106, 110068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagud-Romero, S.; Montesinos, J.; Pascual, M.; Aguilar, M.A.; Roger-Sanchez, C.; Guerri, C.; Miñarro, J.; Rodríguez-Arias, M. Up-Regulation of Histone Acetylation Induced by Social Defeat Mediates the Conditioned Rewarding Effects of Cocaine. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 70, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilen, M.; Ibrahim, P.; Barmo, N.; Abou Haidar, E.; Karnib, N.; El Hayek, L.; Khalifeh, M.; Jabre, V.; Houbeika, R.; Stephan, J.S.; et al. Methionine Mediates Resilience to Chronic Social Defeat Stress by Epigenetic Regulation of NMDA Receptor Subunit Expression. Psychopharmacology 2020, 237, 3007–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, M.; Ellenbroek, B.; Shao, F.; Wang, W. Effects of Adolescent Social Stress and Antidepressant Treatment on Cognitive Inflexibility and Bdnf Epigenetic Modifications in the mPFC of Adult Mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 88, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wilkinson, M.; Liu, X.; Purushothaman, I.; Ferguson, D.; Vialou, V.; Maze, I.; Shao, N.; Kennedy, P.; Koo, J.; et al. Chronic cocaine-regulated epigenomic changes in mouse nucleus accumbens. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R65, Erratum in Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 227. [Google Scholar]

- Hing, B.; Braun, P.; Cordner, Z.A.; Ewald, E.R.; Moody, L.; McKane, M.; Willour, V.L.; Tamashiro, K.L.; Potash, J.B. Chronic Social Stress Induces DNA Methylation Changes at an Evolutionary Conserved Intergenic Region in Chromosome X. Epigenetics 2018, 13, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehner, J.N.; Walia, N.R.; Seong, R.; Li, Y.; Martinez-Feduchi, P.; Yao, B. Social Defeat Stress Induces Genome-Wide 5mC and 5hmC Alterations in the Mouse Brain. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2023, 13, jkad114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, F.S.; Fischl, H.; Murray, S.C.; Mellor, J. Is H3K4me3 Instructive for Transcription Activation? BioEssays 2017, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondar, N.; Bryzgalov, L.; Ershov, N.; Gusev, F.; Reshetnikov, V.; Avgustinovich, D.; Tenditnik, M.; Rogaev, E.; Merkulova, T. Molecular Adaptations to Social Defeat Stress and Induced Depression in Mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 3394–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.-Z.; Zhang, W.-H.; Zheng, Z.-H.; Zou, J.-X.; Liu, X.-X.; Huang, S.-H.; You, W.-J.; He, Y.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Wang, X.-D.; et al. Identification of a Prefrontal Cortex-to-Amygdala Pathway for Chronic Stress-Induced Anxiety. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, B.D.; Duman, R.S. Prefrontal Cortex Circuits in Depression and Anxiety: Contribution of Discrete Neuronal Populations and Target Regions. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 2742–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Era, V.; Carnevali, L.; Thayer, J.F.; Candidi, M.; Ottaviani, C. Dissociating Cognitive, Behavioral and Physiological Stress-Related Responses through Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Inhibition. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 124, 105070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzagalli, D.A.; Roberts, A.C. Prefrontal Cortex and Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 225–246, Erratum in Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetnikov, V.V.; Kisaretova, P.E.; Ershov, N.I.; Merkulova, T.I.; Bondar, N.P. Data of Correlation Analysis between the Density of H3K4me3 in Promoters of Genes and Gene Expression: Data from RNA-Seq and ChIP-Seq Analyses of the Murine Prefrontal Cortex. Data Brief 2020, 33, 106365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Gong, X.; Yao, X.; Guang, Y.; Yang, H.; Ji, R.; He, Y.; Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; et al. Prolonged Chronic Social Defeat Stress Promotes Less Resilience and Higher Uniformity in Depression-like Behaviors in Adult Male Mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 553, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasca, C.; Menard, C.; Hodes, G.; Bigio, B.; Pena, C.; Lorsch, Z.; Zelli, D.; Ferris, A.; Kana, V.; Purushothaman, I.; et al. Multidimensional Predictors of Susceptibility and Resilience to Social Defeat Stress. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 86, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, V.; Han, M.-H.; Graham, D.L.; Berton, O.; Renthal, W.; Russo, S.J.; LaPlant, Q.; Graham, A.; Lutter, M.; Lagace, D.C.; et al. Molecular Adaptations Underlying Susceptibility and Resistance to Social Defeat in Brain Reward Regions. Cell 2007, 131, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milic, M.; Schmitt, U.; Lutz, B.; Müller, M.B. Individual Baseline Behavioral Traits Predict the Resilience Phenotype after Chronic Social Defeat. Neurobiol. Stress 2021, 14, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques-Alves, A.M.; Queiroz, C.M. Ethological Evaluation of the Effects of Social Defeat Stress in Mice: Beyond the Social Interaction Ratio. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 9, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.-M.; Moffat, J.J.; Liu, J.; Dravid, S.M.; Gurumurthy, C.B.; Kim, W.-Y. Arid1b Haploinsufficiency Disrupts Cortical Interneuron Development and Mouse Behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 1694–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffat, J.J.; Smith, A.L.; Jung, E.-M.; Ka, M.; Kim, W.-Y. Neurobiology of ARID1B Haploinsufficiency Related to Neurodevelopmental and Psychiatric Disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartosovic, M.; Kabbe, M.; Castelo-Branco, G. Single-Cell CUT&Tag Profiles Histone Modifications and Transcription Factors in Complex Tissues. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Wen, Z.; Tao, H.; Liao, H. Improved ChIP Sequencing for H3K27ac Profiling and Super-Enhancer Analysis Assisted by Fluorescence-Activated Sorting of Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tissues. Biol. Proced. Online 2025, 27, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Park, J.; Susztak, K.; Zhang, N.R.; Li, M. Bulk Tissue Cell Type Deconvolution with Multi-Subject Single-Cell Expression Reference. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.M.; Steen, C.B.; Liu, C.L.; Gentles, A.J.; Chaudhuri, A.A.; Scherer, F.; Khodadoust, M.S.; Esfahani, M.S.; Luca, B.A.; Steiner, D.; et al. Determining Cell Type Abundance and Expression from Bulk Tissues with Digital Cytometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschendorff, A.E.; Zhu, T.; Breeze, C.E.; Beck, S. EPISCORE: Cell Type Deconvolution of Bulk Tissue DNA Methylomes from Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Liu, J.; Beck, S.; Pan, S.; Capper, D.; Lechner, M.; Thirlwell, C.; Breeze, C.E.; Teschendorff, A.E. A Pan-Tissue DNA Methylation Atlas Enables in Silico Decomposition of Human Tissue Methylomes at Cell-Type Resolution. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carulli, D.; De Winter, F.; Verhaagen, J. Semaphorins in Adult Nervous System Plasticity and Disease. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2021, 13, 672891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alto, L.T.; Terman, J.R. Semaphorins and Their Signaling Mechanisms. In Semaphorin Signaling; Terman, J.R., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1493, pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-1-4939-6446-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rashford, R.L.; DeBerardine, M.; Dan, S.; Bennett, S.N.; Peña, C.J. Persistent Open Chromatin State in Early-Life Stress-Activated Cells of the VTA. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisek, M.; Przybyszewski, O.; Zylinska, L.; Guo, F.; Boczek, T. The Role of MEF2 Transcription Factor Family in Neuronal Survival and Degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwell, C.L.; Maldonado-Lasunción, I.; Eggers, R.; Bijleveld, B.A.; Ellenbroek, W.M.; Siersema, N.; Razenberg, L.; Lamme, D.; Fagoe, N.D.; Van Kesteren, R.E.; et al. The Transcription Factor Combination MEF2 and KLF7 Promotes Axonal Sprouting in the Injured Spinal Cord with Functional Improvement and Regeneration-Associated Gene Expression. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielewski, S.; Piaszyk-Borychowska, A.; Wesoly, J.; Bluyssen, H.A.R. STAT1 and IRF8 in Vascular Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Potential. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 35, 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imitola, J.; Hollingsworth, E.W.; Watanabe, F.; Olah, M.; Elyaman, W.; Starossom, S.; Kivisäkk, P.; Khoury, S.J. Stat1 Is an Inducible Transcriptional Repressor of Neural Stem Cells Self-Renewal Program during Neuroinflammation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1156802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, B.; Cai, J.; Peng, Q.; Hu, J.; Askar, P.; Shangguan, J.; Su, W.; Zhu, C.; Sun, H.; et al. The Transcription Factor Stat-1 Is Essential for Schwann Cell Differentiation, Myelination and Myelin Sheath Regeneration. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, H.; Yasui, Y.; Oiso, K.; Ochi, T.; Tomonobu, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Kinoshita, R.; Sakaguchi, M. STAT1/3 Signaling Suppresses Axon Degeneration and Neuronal Cell Death through Regulation of NAD+-Biosynthetic and Consuming Enzymes. Cell. Signal. 2023, 108, 110717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antontseva, E.; Bondar, N.; Reshetnikov, V.; Merkulova, T. The Effects of Chronic Stress on Brain Myelination in Humans and in Various Rodent Models. Neuroscience 2020, 441, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Melo, D.; Galleguillos, D.; Sánchez, N.; Gysling, K.; Andrés, M.E. Nur Transcription Factors in Stress and Addiction. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2013, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Chai, W.; Min, J.; Qu, X. Yin Yang 1 Suppresses Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress Injury in SH-SY5Y Cells by Facilitating NR4A1 Expression. J. Neurogenet. 2023, 37, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévesque, D.; Rouillard, C. Nur77 and Retinoid X Receptors: Crucial Factors in Dopamine-Related Neuroadaptation. Trends Neurosci. 2007, 30, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawk, J.D.; Abel, T. The Role of NR4A Transcription Factors in Memory Formation. Brain Res. Bull. 2011, 85, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khantakova, J.N.; Mutovina, A.; Ayriyants, K.A.; Bondar, N.P. Th17 Cells, Glucocorticoid Resistance, and Depression. Cells 2023, 12, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.-Q.; Wu, G.-H.; Wang, X.-C.; Xiong, X.-W.; Wang, R.; Yao, B.-L. The Role of Foxo3a in Neuron-Mediated Cognitive Impairment. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1424561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Chen, L.; Yang, S.; Li, F.; Li, X. Behavioral Stress-Induced Activation of FoxO3a in the Cerebral Cortex of Mice. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 71, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, V.S.; Torres, F.F.; Da Silva, D.G.H. FoxO3 and Oxidative Stress: A Multifaceted Role in Cellular Adaptation. J. Mol. Med. 2023, 101, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourc’h, C.; Dufour, S.; Timcheva, K.; Seigneurin-Berny, D.; Verdel, A. HSF1-Activated Non-Coding Stress Response: Satellite lncRNAs and Beyond, an Emerging Story with a Complex Scenario. Genes 2022, 13, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, H.; Wang, R.; Li, M.; Wang, B.; Wildmann, A.; Ortyl, T.; O’Brien, S.; Young, D.; Liao, F.; Sakata, K. Heat Shock Factor HSF1 Regulates BDNF Gene Promoters upon Acute Stress in the Hippocampus, Together with pCREB. J. Neurochem. 2023, 165, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lax, E.; Do Carmo, S.; Enuka, Y.; Sapozhnikov, D.M.; Welikovitch, L.A.; Mahmood, N.; Rabbani, S.A.; Wang, L.; Britt, J.P.; Hancock, W.W.; et al. Methyl-CpG Binding Domain 2 (Mbd2) Is an Epigenetic Regulator of Autism-Risk Genes and Cognition. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.R.; Zhou, Z. Genomic Insights into MeCP2 Function: A Role for the Maintenance of Chromatin Architecture. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2019, 59, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, C.; Hoffmann, A.; Raabe, F.; Spengler, D. Role of Mecp2 in Experience-Dependent Epigenetic Programming. Genes 2015, 6, 60–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Lafuente, C.L.; Kalynchuk, L.E.; Caruncho, H.J.; Ausió, J. The Role of MeCP2 in Regulating Synaptic Plasticity in the Context of Stress and Depression. Cells 2022, 11, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; He, L.; Ma, R.; Ding, W.; Zhou, C.; Lin, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Yao, W. The Role of MeCP2 and the BDNF/TrkB Signaling Pathway in the Stress Resilience of Mice Subjected to CSDS. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 2921–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, S.D.; Veile, R.A.; Donis-Keller, H.; Baraban, J.M.; Bhat, R.V.; Simburger, K.S.; Milbrandt, J. Neural-Specific Expression, Genomic Structure, and Chromosomal Localization of the Gene Encoding the Zinc-Finger Transcription Factor NGFI-C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 4739–4743, Erratum in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, A.M.; Wilce, P.A. Egr Transcription Factors in the Nervous System. Neurochem. Int. 1997, 31, 477–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.; Brandon, N. Emerging Biology of PDE10A. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 21, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, E.; Prickaerts, J. Phosphodiesterases in Neurodegenerative Disorders. IUBMB Life 2012, 64, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.-L.; Whelan, F.; Deloukas, P.; Whittaker, P.; Delgado, M.; Cantor, R.M.; McCann, S.M.; Licinio, J. Phosphodiesterase Genes Are Associated with Susceptibility to Major Depression and Antidepressant Treatment Response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 15124–15129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, T.R.; Natesan, S.; Niccolini, F.; Politis, M.; Gunn, R.N.; Searle, G.E.; Howes, O.; Rabiner, E.A.; Kapur, S. Phosphodiesterase 10A in Schizophrenia: A PET Study Using [11C]IMA107. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.L.; Kelley, J.R.; Klose, R.J. Understanding the Interplay between CpG Island-Associated Gene Promoters and H3K4 Methylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Gene Regul. Mech. 2020, 1863, 194567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, L.M.; He, P.C.; Chun, Y.; Suh, H.; Kim, T.; Buratowski, S. Determinants of Histone H3K4 Methylation Patterns. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 773–785.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtseva, N.N.; Bakshtanovskaya, I.V.; Koryakina, L.A. Social Model of Depression in Mice of C57BL/6J Strain. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1991, 38, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtseva, N.N. Use of the “Partition” Test in Behavioral and Pharmacological Experiments. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 2003, 33, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagné, V.; Moser, P.; Roux, S.; Porsolt, R.D. Rodent Models of Depression: Forced Swim and Tail Suspension Behavioral Despair Tests in Rats and Mice. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 2011, 55, 8.10A.1–8.10A.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.-S.; Matevossian, A.; Jiang, Y.; Akbarian, S. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation in Postmortem Brain. J. Neurosci. Methods 2006, 156, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ershov, N.I.; Bondar, N.P.; Lepeshko, A.A.; Reshetnikov, V.V.; Ryabushkina, J.A.; Merkulova, T.I. Consequences of Early Life Stress on Genomic Landscape of H3K4me3 in Prefrontal Cortex of Adult Mice. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.-R.; Dunkel, I.; Heise, F.; Linke, C.; Krobitsch, S.; Ehrenhofer-Murray, A.E.; Sperling, S.R.; Vingron, M. The Effect of Micrococcal Nuclease Digestion on Nucleosome Positioning Data. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast Gapped-Read Alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinov, G.K.; Kundaje, A.; Park, P.J.; Wold, B.J. Large-Scale Quality Analysis of Published ChIP-Seq Data. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2014, 4, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Peak Location | log2 FoldChange | p.adj | Gene Name | cCRE Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr5: 129,584,219–129,584,365 | −0.58052 | 0.047 | Mmp17 | PLS |

| chr4: 43,875,569–43,875,715 | −0.51618 | 0.047 | Reck | PLS |

| chr15: 3,979,351–3,979,497 | −0.57101 | 0.069 | Fbxo4 | PLS |

| chr15: 93,595,540–93,595,686 | −0.61697 | 0.069 | Prickle1 | pELS |

| chr9: 75,559,444–75,559,590 | −0.51674 | 0.069 | Tmod3 | PLS |

| chr5: 147,430,238–147,430,384 | −0.49941 | 0.069 | Pan3 | PLS |

| chr17: 49,959,957–4,996,103 | −0.65811 | 0.091 | Arid1b | pELS |

| chr5: 76,184,229–76,184,375 | −0.66802 | 0.094 | Tmem165 | pELS |

| Number of DE Genes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Genes with DE Peaks | S10 (2609 *) | S15 (1201 **) | S30 (2572 *) |

| S10 (1866) | 237 (9.08%) | 189 (15.74%) | 309 (12.01%) |

| S15 (1149) | 235 (9.07%) | 153 (12.74%) | 242 (9.40%) |

| S30 (2127) | 258 (9.89%) | 186 (15.49%) | 351 (13.64%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bondar, N.; Reshetnikov, V.; Ritter, P.; Ershov, N.; Zhukova, N.; Kolmykov, S.; Merkulova, T. Epigenetic Signatures of Social Defeat Stress Varying Duration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010018

Bondar N, Reshetnikov V, Ritter P, Ershov N, Zhukova N, Kolmykov S, Merkulova T. Epigenetic Signatures of Social Defeat Stress Varying Duration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleBondar, Natalya, Vasiliy Reshetnikov, Polina Ritter, Nikita Ershov, Natalia Zhukova, Semyon Kolmykov, and Tatyana Merkulova. 2026. "Epigenetic Signatures of Social Defeat Stress Varying Duration" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010018

APA StyleBondar, N., Reshetnikov, V., Ritter, P., Ershov, N., Zhukova, N., Kolmykov, S., & Merkulova, T. (2026). Epigenetic Signatures of Social Defeat Stress Varying Duration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010018