The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. What Are the Implications of Anesthetic Techniques? A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review Design

3. Neutrophils and the Role of Inflammation in HCC Biology

4. Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation

4.1. Types of NET Formation

4.1.1. Lytic (Suicidal) NET Formation

NADPH Oxidase-Dependent NET Formation

NADPH Oxidase-Independent NET Formation

4.1.2. Vital NET Formation

5. Implications of NETs in HCC Biology

5.1. Effects of NETs on Tumor Growth and Metastasis in HCC

5.2. NETs and Immunosuppression in HCC

5.3. NETs and Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition

6. How Can We Detect and Monitor NETosis? Is It Clinically Relevant and Reliable?

7. NETosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

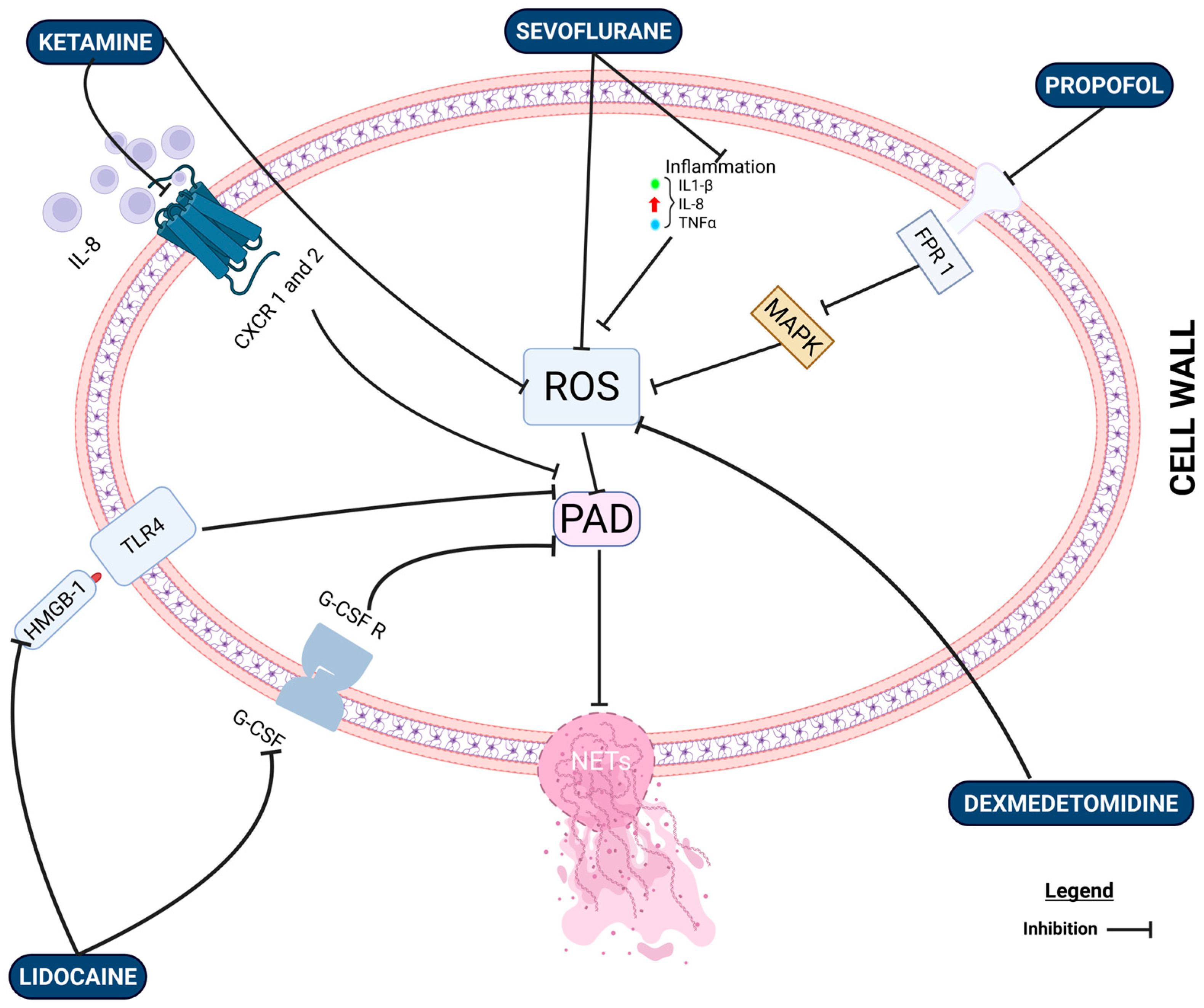

8. The Effects of Anesthetic Drugs on NET Formation: What Is the Clinical Evidence?

8.1. Propofol vs. Inhalational Anesthesia

8.2. Intravenous Lidocaine and NET Formation

8.3. Regional Anesthesia

| Study Design | Cancer Type | Anesthetic Protocol | Number of Participants | NETosis Marker Measured | Effect Observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. (2019) Preclinical [111] | N/A | Propofol, Midazolam, Ketamine, Thiomylol Sodium | N/A | Phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) | Propofol inhibited PMA-induced NET formation |

| Galos et al. (2020) RCT [112] | Breast Cancer | Sevo ± Lidocaine Propofol ± Lidocaine | 120 | MPO, CitH3 | Lidocaine decreased NETosis formation regardless of GA |

| Aghamelu et al. (2020) RCT [113] | Breast Cancer | Volatile + Opioids Propofol + PPA | 40 | MPO, CitH3 | No difference |

| Zhang et al. (2024) RCT [9] | Breast Cancer | Sevo + Lidocaine Propofol + Lidocaine | 120 | MPO, CitH3, NE | No increase in postoperative serum concentration |

| Zhang et al. (2022) RCT [118] | Pancreatic Cancer | Intravenous Lidocaine | 536 | Circulating NETs Tumor-Associated NETs | Intravenous lidocaine did not improve overall DFS |

| Ren et al. (2023) RCT [119] | Lung Cancer | Intravenous Lidocaine Dexmedetomidine | 132 | NETs, MMPs, VEGF | Lidocaine and dexmedetomidine reduced production of NETs according to tumor metastasis biomarkers |

| Wu et al. (2023) RCT [121] | Colorectal Cancer | Propofol–Epidural (PEA) Volatile + Opioids | 60 | MPO, CitH3, MMP-9 | Propofol–PEA reduced NETosis |

8.4. Opioids and NETosis

8.5. Dexmedetomdine and α2 Agonists

8.6. Limitations of Current Studies and Future Research

9. Therapeutic and Clinical Implications

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NETs | neutrophil extracellular traps |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| HCC | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| CitH3 | citrullinated histone |

| MPO-DNA | myeloperoxidase–DNA complex |

| MMP-9 | matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| HBV | hepatitis B virus |

| NAFLD | nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| HBx | HBV X protein |

| HCV | hepatitis C virus |

| DAMPs | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| PAMPs | pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor |

| pSTAT3 | phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 |

| pERK1/2 | extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 |

| SYK | spleen-associated tyrosine kinase |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| TAN N2 | tumor-associated neutrophils N2 |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| IL-8 | interleukin-8 |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1β |

| GM-CSF | granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| IFN-γ | interferon gamma |

| IL-17A | interleukin-17a |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| i.v. | intravenous |

| CCL | chemokine ligand |

| CXCL | chemokine ligand |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| PMA | phorbol myristate acetate |

| DEK | chromatin-binding protein |

| CDK6 | cyclin-dependent kinase 6 |

| PAD4 | peptidyl arginine deaminase 4 |

| GSDMD | protein gasdermin D |

| HMGB1 | damage-associated molecular pattern |

| RAGE | receptor of advanced glycation end-products |

| COX-2 | cyclooxygenase-2 |

| PGE-2 | prostaglandin e2 |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor beta |

| PDGF | platelet-derived growth factor |

| EGF | epidermal growth factor |

| IGF-1 | insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| CCDC25 | coiled-coil domain-containing protein 25 |

| EMT | epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| Src | Src family kinase |

| NK | natural killer |

| Tregs | regulatory T cells |

| MDSCs | myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| CD73 | ecto-5′-nucleotidase |

| Notch2 | neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 2 |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa B |

| A2A | adenosine a2a |

| TMCO6 | transmembrane and coiled-coil domain 6 |

| TCR | T-cell receptor |

| G-CSF | granulocyte colony-stimulating factor |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| qPCR | standard quantitative PCR |

| RT-qPCR | reverse transcription PCR |

| cfDNA | cell-free DNA |

| ELANE | neutrophil elastase |

| DNA-ase | deoxyribonuclease |

| TIVA | total intravenous anesthesia |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| VEGF-A | vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| GA | general anesthesia |

| PAF-R | platelet-activating factor receptor |

| HOCl | hypochlorous acid |

| TACE | transcatheter arterial chemoembolization |

References

- Rumgay, H.; Arnold, M.; Ferlay, J.; Lesi, O.; Cabasag, C.J.; Vignat, J.; Laversanne, M.; McGlynn, K.A.; Soerjomataram, I. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero, J.A.; Kulik, L.M.; Sirlin, C.B.; Zhu, A.X.; Finn, R.S.; Abecassis, M.M.; Roberts, L.R.; Heimbach, J.K. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018, 68, 723–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butensky, S.D.; Billingsley, K.G.; Khan, S.A. Reasonable expansion of surgical candidates for HCC treatment. Clin. Liver Dis. 2024, 23, e0153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Hmadda, W. Anesthetic Approaches and Their Impact on Cancer Recurrence and Metastasis: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, L.; Cui, Q.; Iftikhar, R.; Xia, Y.; Xu, P. Repositioning Lidocaine as an Anticancer Drug: The Role Beyond Anesthesia. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, T.P.; Buggy, D.J. Perioperative Intravenous Lidocaine and Metastatic Cancer Recurrence—A Narrative Review. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 688896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexa, A.L.; Ciocan, A.; Zaharie, F.; Valean, D.; Sargarovschi, S.; Breazu, C.; Al Hajjar, N.; Ionescu, D. The Influence of Intravenous Lidocaine Infusion on Postoperative Outcome and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Colorectal Cancer Patients. A Pilot Study. J. Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 2023, 32, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Fuente, E.; de la Gala, F.; Hortal, J.; Simón, C.; Reyes, A.; Rancan, L.; Calvo, A.; Puig, A.; Vara, E.; Bellón, J.M.; et al. Impact of Intraoperative Lidocaine During Oncologic Lung Resection on Long-Term Outcomes in Primary Lung Cancer: A Post Hoc Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancers 2025, 17, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Bai, Z.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X. Lidocaine Effects on Neutrophil Extracellular Trapping and Angiogenesis Biomarkers in Postoperative Breast Cancer Patients with Different Anesthesia Methods: A Prospective, Randomized Trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024, 24, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, R. Opioids and Cancer Recurrence. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2014, 8, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin-Fenton, D.P.; Heide-Jørgensen, U.; Ahern, T.P.; Lash, T.L.; Christiansen, P.M.; Ejlertsen, B.; Sjøgren, P.; Kehlet, H.; Sørensen, H.T. Opioids and Breast Cancer Recurrence: A Danish Population-Based Cohort Study. Cancer 2015, 121, 3507–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidambaranathan-Reghupaty, S.; Fisher, P.B.; Sarkar, D. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Epidemiology, etiology and molecular classification. Adv. Cancer Res. 2021, 149, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galle, P.R.; Forner, A.; Llovet, J.M.; Mazzaferro, V.; Piscaglia, F.; Raoul, J.L.; Schirmacher, P.; Vilgrain, V. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, J.; Jaques, B.; Chattopadyhay, D.; Lochan, R.; Graham, J.; Das, D.; Aslam, T.; Patanwala, I.; Gaggar, S.; Cole, M.; et al. Hepatocellular cancer: The impact of obesity, type 2 diabetes and a multidisciplinary team. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refolo, M.G.; Messa, C.; Guerra, V.; Carr, B.I.; D’Alessandro, R. Inflammatory Mechanisms of HCC Development. Cancers 2020, 12, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arzumanyan, A.; Reis, H.M.G.P.V.; Feitelson, M.A. Pathogenic mechanisms in HBV- and HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farazi, P.A.; DePinho, R.A. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: From genes to environment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.S.; Sohn, D.H. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Inflammatory Diseases. Immune Netw. 2018, 18, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahm, J.H.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, H.; Yim, S.Y.; Shin, J.-h.; Yoo, J.E.; Ahn, S.H.; Choi, J.S.; Lee, J.-S.; Park, Y.N. Pathological predictive factors for late recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic liver disease. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 1662–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, J.; Liao, Y.; Zou, R.; Zhu, C.; Li, B.; Liang, Y.; Huang, P.; Wang, Z.; et al. Expression of variant isoforms of the tyrosine kinase SYK determines the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 1845–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Yan, X.; Zhang, H. The tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic potential of traditional Chinese medicine. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, L.; Zhao, J.; Niu, Z.; Chen, H.; Cao, G. Tumor Microenvironment Composition and Related Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2023, 10, 2083–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyhan, D.; Allaire, M.; Fu, Y.; Conti, F.; Wang, X.W.; Gao, B.; Lafdil, F. Immune microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: From pathogenesis to immunotherapy. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 1132–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Cervera, A.; Soehnlein, O.; Kenne, E. Neutrophils in chronic inflammatory diseases. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedrick, C.C.; Malanchi, I. Neutrophils in Cancer: Heterogeneous and Multifaceted. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, B.; Sohn, S. Neutrophils in Inflammatory Diseases: Unraveling the Impact of Their Derived Molecules and Heterogeneity. Cells 2023, 12, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Xia, Y.; Su, J.; Quan, F.; Zhou, H.; Li, Q.; Feng, Q.; Lin, C.; Wang, D.; Jiang, Z. Neutrophil diversity and function in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argentiero, A.; Delvecchio, A.; Fasano, R.; Andriano, A.; Caradonna, I.C.; Memeo, R.; Desantis, V. The Complexity of the Tumor Microenvironment in Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Emerging Therapeutic Developments. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Wu, W.; Du, Y.; Yin, H.; Chen, Q.; Yu, W.; Wang, W.; Yu, J.; Liu, L.; Lou, W.; et al. The Evolution and Heterogeneity of Neutrophils in Cancers: Origins, Subsets, Functions, Orchestrations and Clinical Applications. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geh, D.; Leslie, J.; Rumney, R.; Reeves, H.L.; Bird, T.G.; Mann, D.A. Neutrophils as Potential Therapeutic Targets in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollinedo, F. Neutrophil Degranulation, Plasticity, and Cancer Metastasis. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino-Segura, M.; Sicilia, J.; Ballesteros, I.; Hidalgo, A. Strategies of Neutrophil Diversification. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, F.S.; Xu, R. Neutrophils in Liver Diseases: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Targets. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitakis, K.; Mitroulis, I.; Germanidis, G. Tumor-Associated Neutrophils in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Pathogenesis, Prognosis, and Therapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Saxena, S.; Singh, R.K. Neutrophils in the Tumor Microenvironment. In Tumor Microenvironment; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Giese, M.A.; Hind, L.E.; Huttenlocher, A. Neutrophil Plasticity in the Tumor Microenvironment. Blood 2019, 133, 2159–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonacera, A.; Stancanelli, B.; Colaci, M.; Malatino, L. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio: An Emerging Marker of the Relationships between the Immune System and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozawa, H.; Chiu, C.; Hanahan, D. Infiltrating Neutrophils Mediate the Initial Angiogenic Switch in a Mouse Model of Multistage Carcinogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 12493–12498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergers, G.; Brekken, R.; McMahon, G.; Vu, T.H.; Itoh, T.; Tamaki, K.; Tanzawa, K.; Thorpe, P.; Itohara, S.; Werb, Z.; et al. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Triggers the Angiogenic Switch During Carcinogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000, 2, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Nefedova, Y.; Lei, A.; Gabrilovich, D. Neutrophils and PMN-MDSC: Their Biological Role and Interaction with Stromal Cells. Semin. Immunol. 2018, 35, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Shen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Q.; Lu, H.H.; Bo, J. Accumulation of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) Induced by Low Levels of IL-6 Correlates with Poor Prognosis in Bladder Cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 38378–38388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Montero, C.M.; Salem, M.L.; Nishimura, M.I.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; Cole, D.J.; Montero, A.J. Increased Circulating Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Correlate with Clinical Cancer Stage, Metastatic Tumor Burden, and Doxorubicin-Cyclophosphamide Chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2009, 58, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kim, S.J.; Lei, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, H.; Tsung, A. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Homeostasis and Disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, V.; Reichard, U.; Goosmann, C.; Fauler, B.; Uhlemann, Y.; Weiss, D.S.; Weinrauch, Y.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Kill Bacteria. Science 2004, 303, 1532–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, H.; Gomes, S.M.; Thimmappa, P.Y.; Nagareddy, P.R.; Jamora, C.; Joshi, M.B. Cytokine Signalling in Formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps: Implications for Health and Diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2025, 81, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsioumpekou, M.; Krijgsman, D.; Leusen, J.H.W.; Olofsen, P.A. The Role of Cytokines in Neutrophil Development, Tissue Homing, Function and Plasticity in Health and Disease. Cells 2023, 12, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollica Poeta, V.; Massara, M.; Capucetti, A.; Bonecchi, R. Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors: New Targets for Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, A.; Libby, P.; Soehnlein, O.; Aramburu, I.V.; Papayannopoulos, V.; Silvestre-Roig, C. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps: From Physiology to Pathology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 2737–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.; Aziz, M.; Wang, P. The Vitals of NETs. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2021, 110, 787–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, J.; Euler, M.; Schauer, C.; Schett, G.; Herrmann, M.; Knopf, J.; Yaykasli, K.O. Neutrophils’ Extracellular Trap Mechanisms: From Physiology to Pathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papayannopoulos, V.; Metzler, K.D.; Hakkim, A.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil Elastase and Myeloperoxidase Regulate the Formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 191, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talal, S.; Mona, K.; Karem, A.; Yaniv, L.; Reut, H.M.; Ariel, S.; Moran, A.K.; Harel, E.; Campisi-Pinto, S.; Mahmoud, A.A.; et al. Neutrophil Degranulation and Severely Impaired Extracellular Trap Formation at the Basis of Susceptibility to Infections of Hemodialysis Patients. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosazza, T.; Warner, J.; Sollberger, G. NET Formation—Mechanisms and How They Relate to Other Cell Death Pathways. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 3334–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Stadler, S.; Correll, S.; Li, P.; Wang, D.; Hayama, R.; Leonelli, L.; Han, H.; Grigoryev, S.A.; et al. Histone hypercitrullination mediates chromatin decondensation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 184, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douda, D.N.; Khan, M.A.; Grasemann, H.; Palaniyar, N. SK3 channel and mitochondrial ROS mediate NADPH oxidase-independent NETosis induced by calcium influx. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2817–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilsczek, F.H.; Salina, D.; Poon, K.K.; Fahey, C.; Yipp, B.G.; Sibley, C.D.; Robbins, S.M.; Green, F.H.; Surette, M.G.; Sugai, M.; et al. A novel mechanism of rapid nuclear neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 7413–7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, S.; Lv, C.; Tian, Y. NETosis in Tumour Microenvironment of Liver: From Primary to Metastatic Hepatic Carcinoma. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 97, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Dou, Y.; Lu, C.; Han, R.; He, Y. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Tumor Metabolism and Microenvironment. Biomark. Res. 2025, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, L.; Fang, C.; Li, S.; Yuan, S.; Qian, X.; Yin, Y.; Yu, B.; Fu, B.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) Promote Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Metastasis by Suppressing lncRNA MIR503HG to Activate the NF-κB/NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 867516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.Y.; Luo, Q.; Lu, L.; Zhu, W.W.; Sun, H.T.; Wei, R.; Lin, Z.F.; Wang, X.Y.; Wang, C.Q.; Lu, M.; et al. Increased Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Promote Metastasis Potential of Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Provoking Tumorous Inflammatory Response. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Fan, C.; Dong, S.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Zhou, W. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Regulating Tumor Immunity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1297509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozel, I.; Duerig, I.; Domnich, M.; Lang, S.; Pylaeva, E.; Jablonska, J. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Neutrophils, Angiogenesis, and Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, P.T.; Hooks, S.B. Pleiotropic Effects of the COX-2/PGE2 Axis in the Glioblastoma Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1116014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun, J.W.; Yoon, J.H.; Ahn, H.R.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.B.; Lim, S.B.; Park, W.; Kang, T.W.; Baek, G.O.; Yoon, M.G.; et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblast-Derived Secreted Phosphoprotein 1 Contributes to Resistance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma to Sorafenib and Lenvatinib. Cancer Commun. 2023, 43, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; Kelley, R.K.; Villanueva, A.; Singal, A.G.; Pikarsky, E.; Roayaie, S.; Lencioni, R.; Koike, K.; Zucman-Rossi, J.; Finn, R.S. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 6, Correction in Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burn, G.L.; Foti, A.; Marsman, G.; Patel, D.F.; Zychlinsky, A. The Neutrophil. Immunity 2021, 54, 1377–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Wysocki, R.W.; Amoozgar, Z.; Maiorino, L.; Fein, M.R.; Jorns, J.; Schott, A.F.; Kinugasa-Katayama, Y.; Lee, Y.; Won, N.H.; et al. Cancer Cells Induce Metastasis-Supporting Neutrophil Extracellular DNA Traps. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 361ra138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, S.; Ouyang, D.; Ping, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, Q.J.; et al. DNA of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Binds TMCO6 to Impair CD8+ T-cell Immunity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 1613–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turlej, E.; Domaradzka, A.; Radzka, J.; Drulis-Fajdasz, D.; Kulbacka, J.; Gizak, A. Cross-Talk Between Cancer and Its Cellular Environment—A Role in Cancer Progression. Cells 2025, 14, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Dong, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Huang, S.; Tang, D.; Jing, X.; Yu, S.; Zheng, T.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote immune escape in hepatocellular carcinoma by up-regulating CD73 through Notch2. Cancer Lett. 2024, 598, 217098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltenmeier, C.; Simmons, R.L.; Tohme, S.; Yazdani, H.O. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Cancer Metastasis. Cancers 2021, 13, 6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, J. The Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T.; Wu, K.J. Epigenetic Regulation of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition: Focusing on Hypoxia and TGF-β Signaling. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kong, G. Roles and Epigenetic Regulation of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Its Transcription Factors in Cancer Initiation and Progression. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 4643–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddalena, M.; Dimitrov, J.; Mehmood, T.; Terlizzi, C.; Esposito, P.M.H.; Franzese, A.; Pellegrino, S.; De Rosa, V.; Iommelli, F.; Del Vecchio, S. Neutrophil extracellular traps as drivers of epithelial–mesenchymal transition in cancer cells. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1655019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, E.; Rother, N.; Garsen, M.; Hofstra, J.M.; Satchell, S.C.; Hoffmann, M.; Loeven, M.A.; Knaapen, H.K.; van der Heijden, O.W.H.; Berden, J.H.M.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps drive endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins-Cardoso, K.; Almeida, V.H.; Bagri, K.M.; Rossi, M.I.; Mermelstein, C.S.; König, S.; Monteiro, R.Q. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) promote a pro-metastatic phenotype in human breast cancer cells through epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Cancers 2020, 12, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HL, M.C.D.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Leong, H.C.; Makvandi, P.; Rangappa, K.S.; Bishayee, A.; Kumar, A.P.; Sethi, G. Mechanism of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer and Its Regulation by Natural Compounds. Med. Res. Rev. 2023, 43, 1141–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hong, W.; Wei, X. The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannelli, G.; Koudelkova, P.; Dituri, F.; Mikulits, W. Role of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2016, 65, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chan, A.W.; To, K.F.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, J.; Song, C.; Cheung, Y.S.; Lai, P.B.; Cheng, S.H.; et al. SIRT2 overexpression in hepatocellular carcinoma mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transition by protein kinase B/glycogen synthase kinase-3β/β-catenin signaling. Hepatology 2013, 57, 2287–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, S.; Nakazawa, D.; Shida, H.; Miyoshi, A.; Kusunoki, Y.; Tomaru, U.; Ishizu, A. NETosis markers: Quest for specific, objective, and quantitative markers. Clinica Chim. Acta. 2016, 459, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzycka, W.; Homa-Mlak, I.; Mlak, R.; Małecka-Massalska, T. Direct and indirect methods of evaluating the NETosis process. J. Pre-Clin. Clin. Res. 2019, 13, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stoimenou, M.; Tzoros, G.; Skendros, P.; Chrysanthopoulou, A. Methods for the Assessment of NET Formation: From Neutrophil Biology to Translational Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauracher, L.-M.; Posch, F.; Martinod, K.; Grilz, E.; Däullary, T.; Hell, L.; Brostjan, C.; Zielinski, C.; Ay, C.; Wagner, D.D.; et al. Citrullinated histone H3, a biomarker of neutrophil extracellular trap formation, predicts the risk of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 16, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kano, H.; Huq, M.A.; Tsuda, M.; Noguchi, H.; Takeyama, N. Sandwich ELISA for Circulating Myeloperoxidase- and Neutrophil Elastase-DNA Complexes Released from Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Adv. Tech. Biol. Med. 2016, 5, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenlander, R.; Havervall, S.; Magnusson, M.; Engstrand, J.; Ågren, A.; Thålin, C.; Stål, P. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thålin, C.; Daleskog, M.; Göransson, S.P.; Schatzberg, D.; Lasselin, J.; Laska, A.C.; Kallner, A.; Helleday, T.; Wallén, H.; Demers, M. Validation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the quantification of citrullinated histone H3 as a marker for neutrophil extracellular traps in human plasma. Immunol Res. 2017, 65, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaltenmeier, C.T.; Yazdani, H.; van der Windt, D.; Molinari, M.; Geller, D.; Tsung, A.; Tohme, S. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps as a Novel Biomarker to Predict Recurrence-Free and Overall Survival in Patients with Primary Hepatic Malignancies. HPB 2021, 23, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Gui, Y.; Yang, T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, L.; Chen, W.; Wang, B. PD-L1+ Neutrophils Induced NETs in Malignant Ascites Is a Potential Biomarker in HCC. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2024, 73, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharkova, O.; Tay, S.H.; Lee, H.Y.; Shubhita, T.; Ong, W.Y.; Lateef, A.; MacAry, P.A.; Lim, L.H.K.; Connolly, J.E.; Fairhurst, A.M. A Flow Cytometry-Based Assay for High-Throughput Detection and Quantification of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Mixed Cell Populations. Cytom. Part A 2019, 95, 268–278. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, S.; Shimizu, S.; Matsuo, J.; Nishibata, Y.; Kusunoki, Y.; Hattanda, F.; Shida, H.; Nakazawa, D.; Tomaru, U.; Atsumi, T.; et al. Measurement of NET formation in vitro and in vivo by flow cytometry. Cytom. Part A 2017, 91, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavillet, M.; Martinod, K.; Renella, R.; Harris, C.; Shapiro, N.I.; Wagner, D.D.; Williams, D.A. Flow cytometric assay for direct quantification of neutrophil extracellular traps in blood samples. Am. J. Hematol. 2015, 90, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radermecker, C.; Hego, A.; Delvenne, P.; Marichal, T. Identification and Quantitation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Human Tissue Sections. Bio-Protoc. 2021, 11, e4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchetti, L.; Terrenato, I.; Ferretti, M.; Corrado, G.; Goeman, F.; Donzelli, S.; Mandoj, C.; Merola, R.; Zampa, A.; Carosi, M.; et al. Circulating cell free DNA and citrullinated histone H3 as useful biomarkers of NETosis in endometrial cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 151, Correction in J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.Z.; Peng, Z.P.; Liu, X.C.; Guo, H.F.; Zhou, M.M.; Jiang, D.; Ning, W.R.; Huang, Y.F.; Zheng, L.; Wu, Y. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce tumor metastasis through dual effects on cancer and endothelial cells. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2052418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Gu, Z.; Yuan, X.; Jin, R.; Li, J. Prognostic Signature of NETs-Related Genes in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Based on Bulk and Single-Cell Transcriptomics. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2025, 12, 2351–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, A.; Nizet, V. Impact of Anesthetics on Human Neutrophil Function. Anesth. Analg. 2019, 128, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, A.; Chien, J.; Hobohm, L.; Patras, K.A.; Nizet, V.; Corriden, R. Inhibition of Human Neutrophil Extracellular Trap (NET) Production by Propofol and Lipid Emulsion. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yediyıldız, M.B.; Durmuş, İ.; Ak, H.Y.; Taşkın, K.; Ceylan, M.A.D.; Yüce, Y.; Çevik, B.; Aydoğmuş, E. Comparison of inhalation and total intravenous anesthesia on inflammatory markers in microdiscectomy: A double-blind study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2025, 25, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Tao, X.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, S. Effects of Propofol on Macrophage Activation and Function in Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 964771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, D.C.; Margarit, S.C.; Hadade, A.N.; Mocan, T.N.; Miron, N.A.; Sessler, D.I. Choice of Anesthetic Technique on Plasma Concentrations of Interleukins and Cell Adhesion Molecules. Perioper. Med. 2013, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiry, J.C.; Hans, P.; Deby-Dupont, G.; Mouythis-Mickalad, A.; Bonhomme, V.; Lamy, M. Propofol Scavenges Reactive Oxygen Species and Inhibits the Protein Nitration Induced by Activated Polymorphonuclear Neutrophils. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 499, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikawa, K.; Akamatsu, H.; Nishina, K.; Shiga, M.; Maekawa, N.; Obara, H.; Niwa, Y. Propofol Inhibits Human Neutrophil Functions. Anesth. Analg. 1998, 87, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredthauer, A.; Geiger, A.; Gruber, M.; Pfaehler, S.M.; Petermichl, W.; Bitzinger, D.; Metterlein, T.; Seyfried, T. Propofol Ameliorates Exaggerated Human Neutrophil Activation in a LPS Sepsis Model. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 3849–3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, W.; Hamada, T.; Suzuki, J.; Matsuoka, Y.; Omori-Miyake, M.; Kuwahara, M.; Matsumoto, A.; Nomura, S.; Konishi, A.; Yorozuya, T.; et al. Suppressive Effect of the Anesthetic Propofol on the T Cell Function and T Cell-Dependent Immune Responses. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chen, L.; Yue, C.J.; Xu, H.; Cheng, J.; Cornett, E.M.; Kaye, A.D.; Urits, I.; Viswanath, O.; Liu, H. Effects of Propofol and Sevoflurane on T-Cell Immune Function and Th Cell Differentiation in Children with SMPP Undergoing Fibreoptic Bronchoscopy. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 2574–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C.A.; Murray, D.; Doran, P.; Moriarty, D.C.; Sessler, D.I.; Mascha, E.; Kavanagh, B.P.; Buggy, D.J. Anesthetic Technique and the Cytokine and Matrix Metalloproteinase Response to Primary Breast Cancer Surgery. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2010, 35, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.A.; Oh, C.S.; Yoon, T.G.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Yoo, Y.B.; Yang, J.H.; Kim, S.H. The Effect of Propofol and Sevoflurane on Cancer Cell, Natural Killer Cell, and Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte Function in Patients Undergoing Breast Cancer Surgery: An In Vitro Analysis. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciechanowicz, S.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Q.; Cui, J.; Mi, E.; Lian, Q.; Ma, D. Differential Effects of Sevoflurane on the Metastatic Potential and Chemosensitivity of Non-Small-Cell Lung Adenocarcinoma and Renal Cell Carcinoma In Vitro. Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 120, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.-S.; Lin, W.-C.; Yeh, H.-T.; Hu, C.-L.; Sheu, S.-M. Propofol Specifically Reduces PMA-Induced Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation through Inhibition of p-ERK and HOCl. Life Sci. 2019, 221, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galoș, E.V.; Tat, T.F.; Popa, R.; Efrimescu, C.I.; Finnerty, D.; Buggy, D.J.; Ionescu, D.C.; Mihu, C.M. Neutrophil Extracellular Trapping and Angiogenesis Biomarkers after Intravenous or Inhalation Anaesthesia with or without Intravenous Lidocaine for Breast Cancer Surgery: A Prospective, Randomised Trial. Br. J. Anaesth. 2020, 125, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghamelu, O.; Buggy, P.; Smith, G.; Inzitari, R.; Wall, T.; Buggy, D.J. Serum NETosis Expression and Recurrence Risk after Regional or Volatile Anaesthesia during Breast Cancer Surgery: A Pilot, Prospective, Randomised Single-Blind Clinical Trial. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2020, 65, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Shao, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Ding, C.; Zhuang, L.; Sun, J. An Intravenous Anesthetic Drug—Propofol—Influences the Biological Characteristics of Malignant Tumors and Reshapes the Tumor Microenvironment: A Narrative Literature Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1057571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L.K.; Durieux, M.E. Perioperative Use of Intravenous Lidocaine. Anesthesiology 2017, 126, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eipe, N.; Penning, J.; Yazdi, P. Intravenous Lidocaine for Acute Pain: An Evidence-Based Clinical Update. BJA Educ. 2016, 16, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanns, H.; Hollmann, M.W.; Stevens, M.F.; Lirk, P.; Brandenburger, T.; Piegeler, T.; Werdehausen, R. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Systemic Lidocaine in Acute and Chronic Pain: A Narrative Review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qu, M.; Guo, K.; Wang, Y.; Gu, J.; Wu, H.; Zhu, X.; Sun, Z.; Cata, J.P.; Chen, W.; et al. Intraoperative Lidocaine Infusion in Patients Undergoing Pancreatectomy for Pancreatic Cancer: A Mechanistic, Multicentre Randomised Clinical Trial. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 129, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Cheng, M.; Liu, C.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Song, J.; Zhuang, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, R.; et al. Perioperative Lidocaine and Dexmedetomidine Intravenous Infusion Reduce the Serum Levels of NETs and Biomarkers of Tumor Metastasis in Lung Cancer Patients: A Prospective, Single-Center, Double-Blinded, Randomized Clinical Trial. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1101449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efrimescu, C.I.; Buggy, P.M.; Buggy, D.J. Neutrophil Extracellular Trapping Role in Cancer, Metastases, and Cancer-Related Thrombosis: A Narrative Review of the Current Evidence Base. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 23, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Lv, H.; Lou, F.; Yin, H.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y. Effect of Thoracic Epidural Anesthesia on Perioperative Neutrophil Extracellular Trapping Markers in Patients Undergoing Anesthesia and Surgery for Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 7561–7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Guo, H.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, K.; Hu, F.; Xu, Y.; Wan, L.; Zhou, X.; Pan, Y.; Liu, W.; et al. NETs Activate the GAS6-AXL-NLRP3 Axis in Macrophages to Drive Morphine Tolerance. Cell Commun. Signal. 2025, 23, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Gan, T.; Li, Y.; Hu, F.; Hao, N.; Yuan, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, M. Lung Cancer Cells Release High Mobility Group Box 1 and Promote the Formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 5177–5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriden, R.; Schmidt, B.E.; Olson, J.; Okerblom, J.; Masso-Silva, J.A.; Nizet, V.; Meier, A. Dexmedetomidine Does Not Directly Inhibit Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Production. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 128, e51–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Sun, Y.; Lv, J.; Dou, X.; Dai, M.; Sun, S.; Lin, Y. Effects of Dexmedetomidine on Immune Cells: A Narrative Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 829951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.A.; Bissell, B.D. Misdirected Sympathy: The Role of Sympatholysis in Sepsis and Septic Shock. J. Intensive Care Med. 2018, 33, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T.; Ogata, M.; Kawasaki, C.; Ogata, J.; Inoue, Y.; Shigematsu, A. Ketamine Suppresses Proinflammatory Cytokine Production in Human Whole Blood In Vitro. Anesth. Analg. 1999, 89, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, F.; Shao, Y.; Wu, J.; Luo, J.; Yue, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wu, D.; Cata, J.P.; et al. Tumor Metastasis and Recurrence: The Role of Perioperative NETosis. Cancer Lett. 2024, 611, 217413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fares, S.; Wehrle, C.J.; Hong, H.; Sun, K.; Jiao, C.; Zhang, M.; Gross, A.; Allkushi, E.; Uysal, M.; Kamath, S.; et al. Emerging and Clinically Accepted Biomarkers for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2024, 16, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sargarovschi, S.; Alexa, A.L.; Bondar, O.-K.; Ionescu, D. The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. What Are the Implications of Anesthetic Techniques? A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010155

Sargarovschi S, Alexa AL, Bondar O-K, Ionescu D. The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. What Are the Implications of Anesthetic Techniques? A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010155

Chicago/Turabian StyleSargarovschi, Sergiu, Alexandru Leonard Alexa, Oszkar-Karoly Bondar, and Daniela Ionescu. 2026. "The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. What Are the Implications of Anesthetic Techniques? A Narrative Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010155

APA StyleSargarovschi, S., Alexa, A. L., Bondar, O.-K., & Ionescu, D. (2026). The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. What Are the Implications of Anesthetic Techniques? A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010155