Decoding Breast Cancer: Emerging Molecular Biomarkers and Novel Therapeutic Targets for Precision Medicine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology and Risk Factors in Breast Cancer

3. Genetic Basis for Breast Cancer

3.1. Non-Genetic Factors

3.2. Genetic Factors

- High-Penetrance Variants: These genetic variants can occur in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, with cumulative lifetime risks of 55–70% and 45–69%, respectively [63]. However, the risk varies depending on the variant type and the population studied. Other high-penetrance genes are TP53 (Li-Fraumeni syndrome) [64], PTEN (Cowden syndrome), and CDH1 (hereditary lobular carcinoma). These genes have been recognized as responsible for hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes, in addition to their association with breast cancer [65].

- Intermediate Penetrance Variants: These genetic variants have been identified in genes like PALB2, CHEK2, and ATM, and are known to confer a moderate to high risk of developing breast cancer, although a lower risk than that associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 [66]. The estimated cumulative risk, situated between 20 and 50% for PALB2 [67] and 20–40% for CHEK2 [68], relies on factors like family history and demographic group. Regarding ATM, certain variations have also been linked to a moderate risk [69].

3.3. Alterations in Intracellular Signaling Pathways Linked to Breast Cancer

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway: Mutations in the PIK3CA gene described in hormone receptor-positive (HR+) luminal breast carcinomas plus loss of PTEN or hypermethylation of its promoter induce AKT phosphorylation and mTORC1/2 activation [73]. This signaling pathway stimulates cell proliferation and resistance to genotoxic stress. For this reason, this pathway is used as a therapeutic target for PI3K and mTOR inhibitors [74].

- MAPK signaling pathway (RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK): Amplification of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), such as epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2/ERBB2) and fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 (FGFR1), mutations in RAS/BRAF, or cross-activation with the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway induces cell proliferation, improved cell migration and suppression of apoptosis (associated with aggressive phenotypes of breast cancer such as triple-negative (TNBC) and HER2-positive) [75]. Simultaneous activation of the MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways induces adaptive therapeutic resistance [76].

- Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway: Wnt overactivation due to SFRP1 hypermethylation or CTNNB1 mutations leads to nuclear accumulation of β-catenin, which in turn regulates the expression of genes associated with cell plasticity and metastasis. This molecular mechanism has been identified in basal and metaplastic tumors [77]. The interaction of this pathway with the PI3K/AKT and MAPK signaling pathways contributes to tumor heterogeneity and treatment resistance [78].

4. Molecular Basis for Breast Cancer

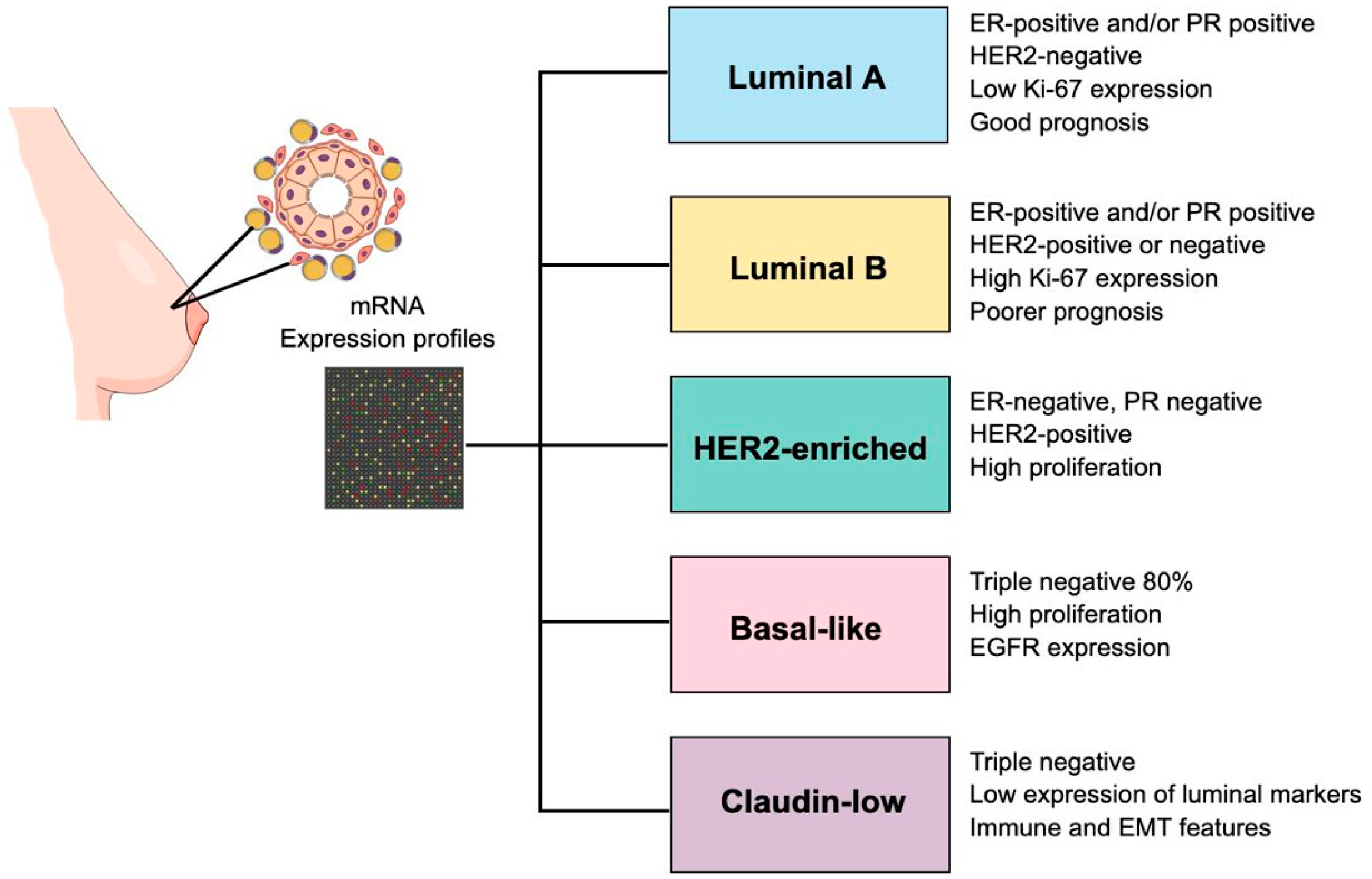

4.1. Establishment of Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancer

4.2. Characteristics of Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes

4.2.1. Luminal A

4.2.2. Luminal B

4.2.3. HER2-Enriched

4.2.4. Basal-like/Triple-Negative (TNBC)

4.2.5. Claudin Low

5. Classic Biomarkers for Breast Cancer

5.1. Hormone Receptors

5.1.1. ER

5.1.2. PR

5.1.3. AR

5.2. HER2/ERBB2

5.3. Ki-67 Cell Proliferation Marker

6. Emerging Molecular Biomarkers for Breast Cancer

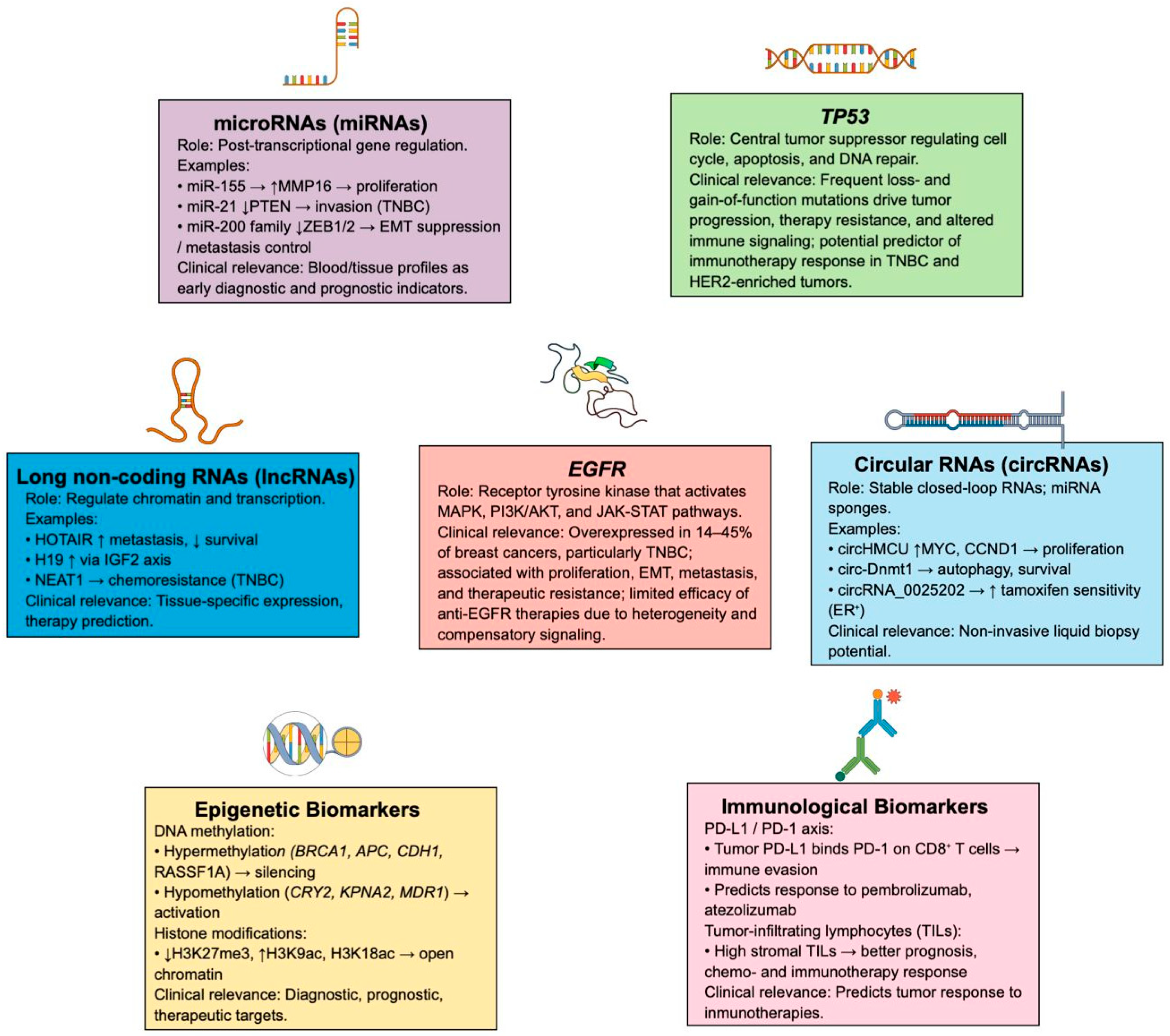

6.1. TP53 Tumor Suppressor Gene

6.2. EGFR/HER1/ERBB1

6.3. Different Types of RNAs

6.3.1. MicroRNAs

6.3.2. lncRNAs

6.3.3. circRNAs

6.4. Epigenetic Biomarkers

6.4.1. DNA Methylation in Promoter Regions

6.4.2. Histone Modifications

6.5. Immunological Biomarkers

6.5.1. PD-L1

6.5.2. TILs

7. Advancements in Liquid Biopsy for the Clinical Management of Breast Cancer

8. Emerging Therapeutic Targets and Their Clinical Application in Breast Cancer

8.1. Therapies Targeting Altered Signaling Pathways in Breast Cancer

8.2. Immunotherapy and Checkpoint Inhibitors

8.3. Nucleic Acid–Based Therapies

8.4. Nanotechnology Applied to Targeted Drug Delivery

8.5. Limitations in Emerging Therapeutics for Breast Cancer

8.6. Clinical Application of Classic and Emerging Biomarkers in Breast Cancer

8.6.1. Utility in Early Diagnosis and Risk Stratification

8.6.2. Role in Therapeutic Selection and Response Monitoring

9. Current Limitations in the Clinical Assessment of Classic and Emerging Biomarkers for Breast Cancer

10. Current Challenges in the Implementation of Liquid Biopsy at the Clinical Setting for Breast Cancer Management

11. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABC | Advanced breast cancer |

| ADC | Antibody–drug conjugate |

| AE | Adverse effects |

| AR | Androgen receptor |

| AREG | Amphiregulin |

| ASCO | American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| CD8+ | Cytotoxic T lymphocytes |

| CDK4/6i | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 inhibitor |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| circRNAs | Circular RNAs |

| CTCs | Circulating tumor cells |

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA |

| D | Hinge region |

| DBD | DNA-binding domain |

| DCIS | Ductal carcinoma in situ |

| DFS | Disease-free survival |

| ddPCR | Droplet digital PCR |

| dMMR | Deficient Mismatch Repair |

| EBC | Early breast cancer |

| ECD | Extracellular domain |

| EGFR/HER1/ERBB1 | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| ER | Estrogen receptors |

| ESCAT | ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of molecular Targets |

| ESMO | European Society for Medical Oncology |

| ESR1 | Estrogen Receptor 1 |

| FM-miR-34a | Fully modified version of miR-34a |

| gBRCA1/2 | Germline BRCA1/2 |

| H3k27me | H3 lysine 27 trimethylation |

| HATs | Histone acetyltransferases |

| HBEGF | Heparin-Binding EGF-Like Growth Factor |

| HDACs | Histone deacetylases |

| HDI | Human Development Index |

| HDR | Homologous Recombination Deficiency |

| HER2 | Growth factor receptor-2 |

| HER2/ERBB2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 |

| HMTs | Histone methyltransferases |

| HOTAIR | HOX transcript antisense intergenic RNA |

| HR+ | Hormone receptor-positive |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IKWG | International Ki67 in Breast Cancer Working Group |

| ISH | In Situ Hybridization |

| LAR | Luminal androgen receptor |

| LDB | Ligand-binding domain |

| LI | Labeling index |

| lncRNAs | Long non-coding RNAs |

| MBC | Metastatic Breast Cancer |

| miRNAs | MicroRNAs |

| MSI-H | Microsatellite Instability–High |

| ncRNAs | non-coding RNAs |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| NK | Natural killer cells |

| NTRK | Neurotrophic Tyrosine Receptor Kinase |

| oncomiRs | Oncogenic miRNAs |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PARP | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PIK3CA | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Alpha |

| PR | Progesterone receptors |

| PROTACs | Proteolysis-targeting chimeras |

| PRS | Polygenic risk score |

| RTKs | Receptor tyrosine kinases |

| S1P | Sphingosine-1-phosphate |

| SERDs | Selective Estrogen Receptor Degraders |

| SNPs | Single nucleotide polymorphisms |

| TAD | Transactivation domain |

| TCGA | Cancer Genome Atlas |

| T-DXd | Trastuzumab deruxtecan |

| TEPs | Tumor-educated platelets |

| TILs | Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes |

| TMB | Tumor Mutational Burden |

| TMD | Transmembrane domain |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| TROP2 | Trophoblast Cell-Surface Antigen 2 |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Turashvili, G.; Brogi, E. Tumor Heterogeneity in Breast Cancer. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, E.; Lindeman, G.J.; Visvader, J.E. Deciphering Breast Cancer: From Biology to the Clinic. Cell 2023, 186, 1708–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Zheng, L.W.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Cai, Y.W.; Wang, L.P.; Huang, L.; Liu, C.C.; Shao, Z.M.; Yu, K. Da Breast Cancer: Pathogenesis and Treatments. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Gonzalez, L.; Sanchez Cendra, A.; Sanchez Cendra, C.; Roberts Cervantes, E.D.; Espinosa, J.C.; Pekarek, T.; Fraile-Martinez, O.; García-Montero, C.; Rodriguez-Slocker, A.M.; Jiménez-Álvarez, L.; et al. Exploring Biomarkers in Breast Cancer: Hallmarks of Diagnosis, Treatment, and Follow-Up in Clinical Practice. Medicina 2024, 60, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beňačka, R.; Szabóová, D.; Guľašová, Z.; Hertelyová, Z.; Radoňák, J. Classic and New Markers in Diagnostics and Classification of Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassy, E.; Mosele, M.F.; Di Meglio, A.; Pistilli, B.; Andre, F. Precision Oncology in Patients with Breast Cancer: Towards a ‘Screen and Characterize’ Approach. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papalexis, P.; Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Drossos, P.V.; Thymara, E.; Nonni, A.; Lazaris, A.C.; Zografos, G.; Spandidos, D.; Kavantzas, N.; Thomopoulou, G.E. Precision Medicine in Breast Cancer (Review). Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Kim, J.; Harper, A.; McCormack, V.; Sung, H.; Houssami, N.; Morgan, E.; Mutebi, M.; Garvey, G.; Soerjomataram, I.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.M. Global Patterns and Trends in Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality across 185 Countries. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today (Version 1.1). Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukasiewicz, S.; Czeczelewski, M.; Forma, A.; Baj, J.; Sitarz, R.; Stanisławek, A. Breast Cancer-Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies-An Updated Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endogenous Hormones and Breast Cancer Collaborative Group; Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Reeves, G.K.; Travis, R.C.; Alberg, A.J.; Barricarte, A.; Berrino, F.; Krogh, V.; Sieri, S.; et al. Sex Hormones and Risk of Breast Cancer in Premenopausal Women: A Collaborative Reanalysis of Individual Participant Data from Seven Prospective Studies. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, C.C. Impact of Aging on the Biology of Breast Cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2008, 66, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, A.; Brown, J.; Malone, C.; McLaughlin, R.; Kerin, M. Effects of Age on the Detection and Management of Breast Cancer. Cancers 2015, 7, 908–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, H.R.; Jones, M.E.; Schoemaker, M.J.; Ashworth, A.; Swerdlow, A.J. Family History and Risk of Breast Cancer: An Analysis Accounting for Family Structure. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 165, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hao, X.; Song, Z.; Zhi, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J. Correlation between Family History and Characteristics of Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiovitz, S.; Korde, L.A. Genetics of Breast Cancer: A Topic in Evolution. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baretta, Z.; Mocellin, S.; Goldin, E.; Olopade, O.I.; Huo, D. Effect of BRCA Germline Mutations on Breast Cancer Prognosis. Medicine 2016, 95, e4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.A.; Prossnitz, E.R.; Royce, M.; Nibbe, A. Temporal Trends in Breast Cancer Survival by Race and Ethnicity: A Population-Based Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedjou, C.G.; Sims, J.N.; Miele, L.; Noubissi, F.; Lowe, L.; Fonseca, D.D.; Alo, R.A.; Payton, M.; Tchounwou, P.B. Health and Racial Disparity in Breast Cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1152, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2024–2025; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer Menarche, Menopause, and Breast Cancer Risk: Individual Participant Meta-Analysis, Including 118 964 Women with Breast Cancer from 117 Epidemiological Studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 1141–1151. [CrossRef]

- Bodewes, F.T.H.; van Asselt, A.A.; Dorrius, M.D.; Greuter, M.J.W.; de Bock, G.H. Mammographic Breast Density and the Risk of Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Breast 2022, 66, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtary, A.; Karakatsanis, A.; Valachis, A. Mammographic Density Changes over Time and Breast Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacht, D.V.; Yamaguchi, K.; Lai, J.; Kulkarni, K.; Sennett, C.A.; Abe, H. Importance of a Personal History of Breast Cancer as a Risk Factor for the Development of Subsequent Breast Cancer: Results From Screening Breast MRI. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2014, 202, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrstad, S.W.; Yan, Y.; Fowler, A.M.; Colditz, G.A. Breast Cancer Risk Associated with Benign Breast Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 149, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, N.; Wang, Z.; Ling, Y.; Hou, G.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Shi, M.; Chu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; et al. Radiotherapy and Increased Risk of Second Primary Cancers in Breast Cancer Survivors: An Epidemiological and Large Cohort Study. Breast 2024, 78, 103824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, R.; Lakshmanaswamy, R. Pregnancy and Breast Cancer. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2017, 151, 81–111. [Google Scholar]

- Stordal, B. Breastfeeding Reduces the Risk of Breast Cancer: A Call for Action in High-income Countries with Low Rates of Breastfeeding. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 4616–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliavacca Zucchetti, B.; Peccatori, F.A.; Codacci-Pisanelli, G. Pregnancy and Lactation: Risk or Protective Factors for Breast Cancer? In Diseases of the Breast During Pregnancy and Lactation; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Alipour, S., Omranipour, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1252, pp. 195–197. [Google Scholar]

- Narod, S.A. Hormone Replacement Therapy and the Risk of Breast Cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 8, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinogradova, Y.; Coupland, C.; Hippisley-Cox, J. Use of Hormone Replacement Therapy and Risk of Breast Cancer: Nested Case-Control Studies Using the QResearch and CPRD Databases. BMJ 2020, 371, m3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, R.N.; Hyer, M.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Adam, E.; Bond, B.; Cheville, A.L.; Colton, T.; Hartge, P.; Hatch, E.E.; Herbst, A.L.; et al. Adverse Health Outcomes in Women Exposed In Utero to Diethylstilbestrol. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1304–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilakivi-Clarke, L. Maternal Exposure to Diethylstilbestrol during Pregnancy and Increased Breast Cancer Risk in Daughters. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 16, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Q.; Tan, X. Physical Activity and Risk of Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of 38 Cohort Studies in 45 Study Reports. Value Health 2019, 22, 104–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Suen, S.C.; Lewis, S.J.; Martin, R.M.; English, D.R.; Boyle, T.; Giles, G.G.; Michailidou, K.; Bolla, M.K.; Wang, Q.; Dennis, J.; et al. Physical Activity, Sedentary Time and Breast Cancer Risk: A Mendelian Randomisation Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boraka, Ö.; Klintman, M.; Rosendahl, A.H. Physical Activity and Long-Term Risk of Breast Cancer, Associations with Time in Life and Body Composition in the Prospective Malmö Diet and Cancer Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehesh, T.; Fadaghi, S.; Seyedi, M.; Abolhadi, E.; Ilaghi, M.; Shams, P.; Ajam, F.; Mosleh-Shirazi, M.A.; Dehesh, P. The Relation between Obesity and Breast Cancer Risk in Women by Considering Menstruation Status and Geographical Variations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starek-Świechowicz, B.; Budziszewska, B.; Starek, A. Alcohol and Breast Cancer. Pharmacol. Rep. 2023, 75, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Si, Y.; Li, X.; Hong, J.; Yu, C.; He, N. The Relationship between Tobacco and Breast Cancer Incidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 961970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, S.; Beydoun, M.A.; Beydoun, H.A.; Chen, X.; Zonderman, A.B.; Wood, R.J. Vitamin D and Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2019, 30, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Liu, Z.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Tang, N.; Li, H. Light at Night Exposure and Risk of Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1276290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Alsabawi, Y.; El-Serag, H.B.; Thrift, A.P. Exposure to Light at Night and Risk of Cancer: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Data Synthesis. Cancers 2024, 16, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiolet, T.; Srour, B.; Sellem, L.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Méjean, C.; Deschasaux, M.; Fassier, P.; Latino-Martel, P.; Beslay, M.; et al. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Cancer Risk: Results from NutriNet-Santé Prospective Cohort. BMJ 2018, 360, k322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugalde-Resano, R.; Gamboa-Loira, B.; Mérida-Ortega, Á.; Rincón-Rubio, A.; Flores-Collado, G.; Piña-Pozas, M.; López-Carrillo, L. Biological Concentrations of DDT Metabolites and Breast Cancer Risk: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rev. Environ. Health 2024, 40, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W. Association between Long-Term Ambient Air Pollution Exposure and the Incidence of Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis Based on Updated Evidence. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 289, 117472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.A.; Goyal, A.; Terry, M.B. Alcohol Intake and Breast Cancer Risk: Weighing the Overall Evidence. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2013, 5, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesnage, R.; Phedonos, A.; Arno, M.; Balu, S.; Corton, J.C.; Antoniou, M.N. Editor’s Highlight: Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Bisphenol A Alternatives Activate Estrogen Receptor Alpha in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 158, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stordal, B.; Harvie, M.; Antoniou, M.N.; Bellingham, M.; Chan, D.S.M.; Darbre, P.; Karlsson, O.; Kortenkamp, A.; Magee, P.; Mandriota, S.; et al. Breast Cancer Risk and Prevention in 2024: An Overview from the Breast Cancer UK-Breast Cancer Prevention Conference. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer and Breastfeeding: Collaborative Reanalysis of Individual Data from 47 Epidemiological Studies in 30 Countries, Including 50 302 Women with Breast Cancer and 96 973 Women without the Disease. Lancet 2002, 360, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teras, L.R.; Patel, A.V.; Wang, M.; Yaun, S.-S.; Anderson, K.; Brathwaite, R.; Caan, B.J.; Chen, Y.; Connor, A.E.; Eliassen, A.H.; et al. Sustained Weight Loss and Risk of Breast Cancer in Women 50 Years and Older: A Pooled Analysis of Prospective Data. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 112, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldado-Gordillo, A.; Álvarez-Mercado, A.I. Epigenetics, Microbiota, and Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Life 2024, 14, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Fang, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, T.; Chen, Q.; Liu, H. Progress in Epigenetic Research of Breast Cancer: A Bibliometric Analysis since the 2000s. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1619346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Luo, Y.; Tong, S.; Liu, Y. EZH2: The Roles in Targeted Therapy and Mechanisms of Resistance in Breast Cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 175, 116624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellesi, E.; Savini, I.; Veneziano, M.; Gambacurta, A.; Catani, M.V.; Gasperi, V. Decoding the Epigenome of Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Mahapatra, S.; Khanra, S.; Mishra, B.; Swain, B.; Malhotra, D.; Saha, S.; Panda, V.K.; Kumari, K.; Jena, S.; et al. Decoding Breast Cancer Treatment Resistance through Genetic, Epigenetic, and Immune-Regulatory Mechanisms: From Molecular Insights to Translational Perspectives. Cancer Drug Resist. 2025, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, P.; Bandlamudi, C.; Jonsson, P.; Kemel, Y.; Chavan, S.S.; Richards, A.L.; Penson, A.V.; Bielski, C.M.; Fong, C.; Syed, A.; et al. The Context-Specific Role of Germline Pathogenicity in Tumorigenesis. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, F.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Schumacher-Wulf, E.; Matos, L.; Gelmon, K.; Aapro, M.S.; Bajpai, J.; Barrios, C.H.; Bergh, J.; Bergsten-Nordström, E.; et al. 6th and 7th International Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Advanced Breast Cancer (ABC Guidelines 6 and 7). Breast 2024, 76, 103756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Lim, A.-R.; Kim, J.W.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, S.; Sung, J.S.; Chung, H.-J.; Jang, B.; Yoon, D.; et al. Genomic Landscape and Clinical Utility in Korean Advanced Pan-Cancer Patients from Prospective Clinical Sequencing: K-MASTER Program. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrucelli, N.; Daly, M.B.; Pal, T. BRCA1- and BRCA2-Associated Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer; Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Eds.; GeneReviews, University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, K.; Zelley, K.; Nichols, K.E.; Schwartz Levine, A.; Garber, J. Li-Fraumeni Syndrome; Adam, M.P., Fedman, J., MIrzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Eds.; GeneReviews, University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Subaşıoğlu, A.; Güç, Z.G.; Gür, E.Ö.; Tekindal, M.A.; Atahan, M.K. Genetic, Surgical and Oncological Approach to Breast Cancer, with BRCA1, BRCA2, CDH1, PALB2, PTEN and TP53 Variants. Eur. J. Breast Health 2023, 19, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.-C.; Moi, S.-H.; Huang, H.-I.; Hsiao, T.-H.; Huang, C.-C. Polygenic Risk Score-Based Prediction of Breast Cancer Risk in Taiwanese Women with Dense Breast Using a Retrospective Cohort Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberu, T.L.M.; Braun, D.; Parmigiani, G.; Biswas, S. Meta-Analysis of Breast Cancer Risk for Individuals with PALB2 Pathogenic Variants. Genet. Epidemiol. 2024, 48, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, H.; Pal, T.; Tischkowitz, M.; Stewart, D. CHEK2-Related Cancer Predisposition; Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Eds.; GeneReviews, University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Seca, M.; Narod, S.A. Breast Cancer and ATM Mutations: Treatment Implications. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2024, 22, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, E.; Howell, S.; Evans, D.G. Polygenic Risk Scores and Breast Cancer Risk Prediction. Breast 2023, 67, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbuya-Bienge, C.; Pashayan, N.; Kazemali, C.D.; Lapointe, J.; Simard, J.; Nabi, H. A Systematic Review and Critical Assessment of Breast Cancer Risk Prediction Tools Incorporating a Polygenic Risk Score for the General Population. Cancers 2023, 15, 5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Mamidi, T.K.K.; Zhang, L.; Hicks, C. Deconvolution of the Genomic and Epigenomic Interaction Landscape of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayama, S.; Nakamura, R.; Ishige, T.; Sangai, T.; Sakakibara, M.; Fujimoto, H.; Ishigami, E.; Masuda, T.; Nakagawa, A.; Teranaka, R.; et al. The Impact of PIK3CA Mutations and PTEN Expression on the Effect of Neoadjuvant Therapy for Postmenopausal Luminal Breast Cancer Patients. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tada, H.; Miyashita, M.; Harada-Shoji, N.; Ebata, A.; Sato, M.; Motonari, T.; Yanagaki, M.; Kon, T.; Sakamoto, A.; Ishida, T. Clinicopathogenomic Analysis of PI3K/AKT/PTEN-Altered Luminal Metastatic Breast Cancer in Japan. Breast Cancer 2025, 32, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, S.; Maurya, R.; Vikal, A.; Patel, P.; Thakur, S.; Singh, A.; Gupta, G.D.; Kurmi, B. Das Understanding Drug Resistance in Breast Cancer: Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Med. Drug Discov. 2025, 26, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, M.E.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.R. Targeting the RAS/RAF/MAPK Pathway for Cancer Therapy: From Mechanism to Clinical Studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Gao, Z.; Bao, Y.; Chen, L.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Q.; Wei, X. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway in Carcinogenesis and Cancer Therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schie, E.H.; Van Amerongen, R. Aberrant WNT/CTNNB1 Signaling as a Therapeutic Target in Human Breast Cancer: Weighing the Evidence. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Molecular Classification of Breast Cancer: Relevance and Challenges. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2023, 147, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perou, C.M.; Sørlie, T.; Eisen, M.B.; Van De Rijn, M.; Jeffrey, S.S.; Ress, C.A.; Pollack, J.R.; Ross, D.T.; Johnsen, H.; Akslen, L.A.; et al. Molecular Portraits of Human Breast Tumours. Nature 2000, 406, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørlie, T.; Perou, C.M.; Tibshirani, R.; Aas, T.; Geisler, S.; Johnsen, H.; Hastie, T.; Eisen, M.B.; Van De Rijn, M.; Jeffrey, S.S.; et al. Gene Expression Patterns of Breast Carcinomas Distinguish Tumor Subclasses with Clinical Implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prat, A.; Perou, C.M. Deconstructing the Molecular Portraits of Breast Cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2011, 5, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, E.; Ulaner, G.A.; Chin, S.F. Molecular Classification of Breast Cancer. PET Clin. 2018, 13, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive Molecular Portraits of Human Breast Tumors. Nature 2012, 490, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschkowitz, J.I.; Simin, K.; Weigman, V.J.; Mikaelian, I.; Usary, J.; Hu, Z.; Rasmussen, K.E.; Jones, L.P.; Assefnia, S.; Chandrasekharan, S.; et al. Identification of Conserved Gene Expression Features between Murine Mammary Carcinoma Models and Human Breast Tumors. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, R76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldhirsch, A.; Winer, E.P.; Coates, A.S.; Gelber, R.D.; Piccart-Gebhart, M.; Thürlimann, B.; Senn, H.J.; Albain, K.S.; André, F.; Bergh, J.; et al. Personalizing the Treatment of Women with Early Breast Cancer: Highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Fowler, A.M.; Ulaner, G.A.; Mahajan, A. Molecular Classification of Breast Cancer. PET Clin. 2023, 18, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makki, J. Diversity of Breast Carcinoma: Histological Subtypes and Clinical Relevance. Clin. Med. Insights Pathol. 2015, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eroles, P.; Bosch, A.; Alejandro Pérez-Fidalgo, J.; Lluch, A. Molecular Biology in Breast Cancer: Intrinsic Subtypes and Signaling Pathways. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2012, 38, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ades, F.; Zardavas, D.; Bozovic-Spasojevic, I.; Pugliano, L.; Fumagalli, D.; De Azambuja, E.; Viale, G.; Sotiriou, C.; Piccart, M. Luminal B Breast Cancer: Molecular Characterization, Clinical Management, and Future Perspectives. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2794–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rediti, M.; Venet, D.; Joaquin Garcia, A.; Maetens, M.; Vincent, D.; Majjaj, S.; El-Abed, S.; Di Cosimo, S.; Ueno, T.; Izquierdo, M.; et al. Identification of HER2-Positive Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes with Potential Clinical Implications in the ALTTO Clinical Trial. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, E.; Canberk, S.; Schmitt, F.; Vale, N. Molecular Subtypes and Mechanisms of Breast Cancer: Precision Medicine Approaches for Targeted Therapies. Cancers 2025, 17, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collignon, J.; Lousberg, L.; Schroeder, H.; Jerusalem, G. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Treatment Challenges and Solutions. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2016, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Duan, J.J.; Bian, X.W.; Yu, S.C. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Molecular Subtyping and Treatment Progress. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasilova, M.L.; Hayse, B.; Killelea, B.K.; Horowitz, N.R.; Chagpar, A.B.; Lannin, D.R. Features of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Analysis of 38,813 Cases from the National Cancer Database. Medicine 2016, 95, e4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.Z.; Ma, D.; Suo, C.; Shi, J.; Xue, M.; Hu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, K.D.; Liu, Y.R.; Yu, Y.; et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Landscape of Triple-Negative Breast Cancers: Subtypes and Treatment Strategies. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 428–440.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, A.; Parker, J.S.; Karginova, O.; Fan, C.; Livasy, C.; Herschkowitz, J.I.; He, X.; Perou, C.M. Phenotypic and Molecular Characterization of the Claudin-Low Intrinsic Subtype of Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010, 12, R68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves Rebello Alves, L.; Dummer Meira, D.; Poppe Merigueti, L.; Correia Casotti, M.; do Prado Ventorim, D.; Ferreira Figueiredo Almeida, J.; Pereira de Sousa, V.; Cindra Sant’Ana, M.; Gonçalves Coutinho da Cruz, R.; Santos Louro, L.; et al. Biomarkers in Breast Cancer: An Old Story with a New End. Genes 2023, 14, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzaman, K.; Karami, J.; Zarei, Z.; Hosseinzadeh, A.; Kazemi, M.H.; Moradi-Kalbolandi, S.; Safari, E.; Farahmand, L. Breast Cancer: Biology, Biomarkers, and Treatments. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 84, 106535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moar, K.; Pant, A.; Saini, V.; Pandey, M.; Maurya, P.K. Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers for Breast Cancer: A Compiled Review. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 251, 154893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clusan, L.; Ferrière, F.; Flouriot, G.; Pakdel, F. A Basic Review on Estrogen Receptor Signaling Pathways in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porras, L.; Ismail, H.; Mader, S. Positive Regulation of Estrogen Receptor Alpha in Breast Tumorigenesis. Cells 2021, 10, 2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, Q.; Khan, M.U.; Fatima, T.; Khalid, S.; Malik, Z.I. Recent Insights Into Breast Cancer: Molecular Pathways, Epigenetic Regulation, and Emerging Targeted Therapies. Breast Cancer 2025, 19, 11782234251355663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mal, R.; Magner, A.; David, J.; Datta, J.; Vallabhaneni, M.; Kassem, M.; Manouchehri, J.; Willingham, N.; Stover, D.; Vandeusen, J.; et al. Estrogen Receptor Beta (ERβ): A Ligand Activated Tumor Suppressor. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 587386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arao, Y.; Korach, K.S. The Physiological Role of Estrogen Receptor Functional Domains. Essays Biochem. 2021, 65, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wei, H.; Li, S.; Wu, P.; Mao, X. The Role of Progesterone Receptors in Breast Cancer. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2022, 16, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, A.; Salem, K.; Fowler, A.M. Progesterone Receptor Gene Polymorphisms and Breast Cancer Risk. Endocrinology 2023, 164, bqad020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, J.M.; Susmi, T.R.; Remadevi, V.; Ravindran, V.; Sasikumar, S.A.; Ayswarya, R.n.S. Sreeja Sreeharshan New Insights into the Functions of Progesterone Receptor (PR) Isoforms and Progesterone Signaling. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 5214–5232. [Google Scholar]

- Heinlein, C.A.; Chang, C. Androgen Receptor (AR) Coregulators: An Overview. Endocr. Rev. 2002, 23, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolyvas, E.A.; Caldas, C.; Kelly, K.; Ahmad, S.S. Androgen Receptor Function and Targeted Therapeutics across Breast Cancer Subtypes. Breast Cancer Res. 2022, 24, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackbart, H.; Cui, X.; Lee, J.S. Androgen Receptor in Breast Cancer and Its Clinical Implication. Transl. Breast Cancer Res. 2023, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Yang, X.; Tai, H.; Zhong, X.; Luo, T.; Zheng, H. HER2-Targeted Therapies in Cancer: A Systematic Review. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieci, M.V.; Miglietta, F.; Griguolo, G.; Guarneri, V. Biomarkers for HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer: Beyond Hormone Receptors. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020, 88, 102064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiò, C.; Annaratone, L.; Marques, A.; Casorzo, L.; Berrino, E.; Sapino, A. Evolving Concepts in HER2 Evaluation in Breast Cancer: Heterogeneity, HER2-Low Carcinomas and Beyond. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 72, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Karim, A.; Ahamed, A.; Hassan, M.K.; Alam, S.S.M.; Ali, S.; Hoque, M. Damaging Non-Synonymous Mutations in the Extracellular Domain of HER2 Potentially Alter the Efficacy of Herceptin-Mediated Breast Cancer Therapy. Egypt. J. Med. Hum. Genet. 2025, 26, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fan, W.; Su, F.; Zhang, X.; Du, Y.; Li, W.; Gao, Y.; Hu, W.; Zhao, J. Discussion on the Mechanism of HER2 Resistance in Esophagogastric Junction and Gastric Cancer in the Era of Immunotherapy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2025, 21, 2459458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiyama, N.; O’Connor, M.; Salomatov, A.; Romashko, D.; Thakur, S.; Mentes, A.; Hopkins, J.F.; Frampton, G.M.; Albacker, L.A.; Kohlmann, A.; et al. Computational and Functional Analyses of HER2 Mutations Reveal Allosteric Activation Mechanisms and Altered Pharmacologic Effects. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 1531–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaibar, M.; Beltrán, L.; Romero-Lorca, A.; Fernández-Santander, A.; Novillo, A. Somatic Mutations in HER2 and Implications for Current Treatment Paradigms in HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. J. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 6375956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; Wang, X.; Fan, C.; Mao, X. The Role of Ki67 in Evaluating Neoadjuvant Endocrine Therapy of Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 687244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreipe, H.; Harbeck, N.; Christgen, M. Clinical Validity and Clinical Utility of Ki67 in Early Breast Cancer. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2022, 14, 17588359221122725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I.; Robertson, J.; Kilburn, L.; Wilcox, M.; Evans, A.; Holcombe, C.; Horgan, K.; Kirwan, C.; Mallon, E.; Sibbering, M.; et al. Long-Term Outcome and Prognostic Value of Ki67 after Perioperative Endocrine Therapy in Postmenopausal Women with Hormone-Sensitive Early Breast Cancer (POETIC): An Open-Label, Multicentre, Parallel-Group, Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1443–1454, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e553. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30677-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Lu, N.; Chen, C.; Lu, X. Identifying the Optimal Cutoff Point of Ki-67 in Breast Cancer: A Single-Center Experience. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 03000605231195468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.O.; Leung, S.C.Y.; Rimm, D.L.; Dodson, A.; Acs, B.; Badve, S.; Denkert, C.; Ellis, M.J.; Fineberg, S.; Flowers, M.; et al. Assessment of Ki67 in Breast Cancer: Updated Recommendations From the International Ki67 in Breast Cancer Working Group. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escala-Cornejo, R.; Olivares-Hernández, A.; García Muñoz, M.; Figuero-Pérez, L.; Vallejo, J.M.; Miramontes-González, J.P.; Sancho de Salas, M.; Gómez Muñoz, M.A.; Tamayo, R.S.; García, G.M.; et al. Identifying the Best Ki-67 Cut-Off for Determining Luminal Breast Cancer Subtypes Using Immunohistochemical Analysis and PAM50 Genomic Classification. EMJ Oncol. 2020, 8, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Borrero, L.J.; El-Deiry, W.S. Tumor Suppressor P53: Biology, Signaling Pathways, and Therapeutic Targeting. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Cancer 2021, 1876, 188556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Baek, S.H.; Lee, M.J.; Kook, Y.; Bae, S.J.; Ahn, S.G.; Jeong, J. Clinical Relevance of TP53 Mutation and Its Characteristics in Breast Cancer with Long-Term Follow-Up Date. Cancers 2024, 16, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulino, P.J.I.V.; Che Omar, M.T. Identification of High-Risk Signatures and Therapeutic Targets through Molecular Characterization and Immune Profiling of TP53-Mutant Breast Cancer. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2025, 23, 100574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, C.; Wang, X. TP53 Mutations Promote Immunogenic Activity in Breast Cancer. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 5952836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tito, C.; Masciarelli, S.; Colotti, G.; Fazi, F. EGF Receptor in Organ Development, Tissue Homeostasis and Regeneration. J. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 32, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyamsunder, S.; Lu, Z.; Takiar, V.; Waltz, S.E. Challenges and Resistance Mechanisms to EGFR Targeted Therapies in Head and Neck Cancers and Breast Cancer: Insights into RTK Dependent and Independent Mechanisms. Oncotarget 2025, 16, 508–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, L.; Chen, C.; Nie, J.; Jiao, B. Can EGFR Be a Therapeutic Target in Breast Cancer? Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Cancer 2022, 1877, 188789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshi, M.; Gandhi, S.; Tokumaru, Y.; Yan, L.; Yamada, A.; Matsuyama, R.; Ishikawa, T.; Endo, I.; Takabe, K. Conflicting Roles of EGFR Expression by Subtypes in Breast Cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 5094–5110. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Rocha, F.; da Silva Maués, J.H.; Brito Lins Pereira, C.M.; Moreira-Nunes, C.A.; Rodriguez Burbano, R.M. Analysis of Increased EGFR and IGF-1R Signaling and Its Correlation with Socio-Epidemiological Features and Biological Profile in Breast Cancer Patients: A Study in Northern Brazil. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2021, 13, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe, M.L.; Marrocco, I.; Yarden, Y. EGFR in Cancer: Signaling Mechanisms, Drugs, and Acquired Resistance. Cancers 2021, 13, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, U.K.; Jenny, L.; Hegde, R.S. IGF-1R Targeting in Cancer—Does Sub-Cellular Localization Matter? J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Kaushik, A.C.; Zhang, J. The Emerging Role of Major Regulatory RNAs in Cancer Control. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Croce, C.M. The Role of MicroRNAs in Human Cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2016, 1, 15004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alles, J.; Fehlmann, T.; Fischer, U.; Backes, C.; Galata, V.; Minet, M.; Hart, M.; Abu-Halima, M.; Grässer, F.A.; Lenhof, H.P.; et al. An Estimate of the Total Number of True Human MiRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 3353–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaschetto, L.M. MiRNA Activation Is an Endogenous Gene Expression Pathway. RNA Biol. 2018, 15, 826–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, G.; Raei, N.; Toofani Milani, A.; Gholizadeh-Ghaleh Aziz, S.; Pourjabbar, N.; Geravand, F. The Emerging Role of MiR-200 Family in Metastasis: Focus on EMT, CSCs, Angiogenesis, and Anoikis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 6935–6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Mitra, T.; Rajiv, R.; Rajan, E.J.E.; Pierret, C.; Enninga, E.A.L.; Janardhanan, R. Exosomal MicroRNAs in Breast Cancer: Towards Theranostic Applications. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1330144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.L.; Sun, J.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhang, H.; Calin, G.A. MiR-200 Family and Cancer: From a Meta-Analysis View. Mol. Asp. Med. 2019, 70, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.K.; Luo, Q.; Peng, H.; Li, J.; Zhao, M.; Wang, J.; Gu, Y.Y.; Li, Y.; Yuan, P.; Zhao, G.H.; et al. A Panel of Serum Noncoding RNAs for the Diagnosis and Monitoring of Response to Therapy in Patients with Breast Cancer. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, N.; Leidinger, P.; Becker, K.; Backes, C.; Fehlmann, T.; Pallasch, C.; Rheinheimer, S.; Meder, B.; Stähler, C.; Meese, E.; et al. Distribution of MiRNA Expression across Human Tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 3865–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelski, W.; Okrasinska, S.; Mroczko, B. MicroRNAs as Biomarkers of Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochor, M.; Basova, P.; Pesta, M.; Dusilkova, N.; Bartos, J.; Burda, P.; Pospisil, V.; Stopka, T. Oncogenic MicroRNAs: MiR-155, MiR-19a, MiR-181b, and MiR-24 Enable Monitoring of Early Breast Cancer in Serum. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X. MicroRNA-21 in Breast Cancer: Diagnostic and Prognostic Potential. Clin. Transl. Oncol. Off. Publ. Fed. Span. Oncol. Soc. 2014, 16, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhavan, D.; Zucknick, M.; Wallwiener, M.; Cuk, K.; Modugno, C.; Scharpff, M.; Schott, S.; Heil, J.; Turchinovich, A.; Yang, R.; et al. Circulating MiRNAs as Surrogate Markers for Circulating Tumor Cells and Prognostic Markers in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 5972–5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, N.; Huang, T.; Shen, N. MicroRNA-200c in Cancer Generation, Invasion, and Metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhong, Q. MicroRNA-200c Inhibits the Metastasis of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Targeting ZEB2, an Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Regulator. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2020, 50, 519–527. [Google Scholar]

- Taha, M.; Mitwally, N.; Soliman, A.S.; Yousef, E. Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Utility of MiR-141, MiR-181b1, and MiR-23b in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Meng, X.; Luo, Y.; Luo, S.; Li, J.; Zeng, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, J. The Oncogenic MiR-429 Promotes Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Progression by Degrading DLC1. Aging 2023, 15, 9809–9821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.B.; Ma, G.; Zhao, Y.H.; Xiao, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Jing, C.; Gao, K.; Liu, Z.H.; Yu, S.J. MiR-429 Inhibits Migration and Invasion of Breast Cancer Cells in Vitro. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xu, T.; Zhou, X.; Liao, L.; Pang, G.; Luo, W.; Han, L.; Zhang, J.; Luo, X.; Xie, X.; et al. Downregulation of MiRNA-141 in Breast Cancer Cells Is Associated with Cell Migration and Invasion: Involvement of ANP32E Targeting. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, A.M.; Sohal, I.S.; Iyer, S.; Sudarshan, K.; Kothandaraman, H.; Lanman, N.A.; Low, P.S.; Kasinski, A.L. A First-in-Class Fully Modified Version of MiR-34a with Outstanding Stability, Activity, and Anti-Tumor Efficacy. Oncogene 2023, 42, 2985–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S. Long Non-Coding RNAs: From Disease Code to Drug Role. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, M.K.; Niknafs, Y.S.; Malik, R.; Singhal, U.; Sahu, A.; Hosono, Y.; Barrette, T.R.; Prensner, J.R.; Evans, J.R.; Zhao, S.; et al. The Landscape of Long Noncoding RNAs in the Human Transcriptome. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.J.; Chang, H.Y. Unique Features of Long Non-Coding RNA Biogenesis and Function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhu, J.; Fu, Y.; Li, C.; Wu, B. LncRNA HOTAIR Promotes Breast Cancer Progression through Regulating the MiR-129-5p/FZD7 Axis. Cancer Biomark. 2021, 30, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, G.S.R.; Pavitra, E.; Bandaru, S.S.; Varaprasad, G.L.; Nagaraju, G.P.; Malla, R.R.; Huh, Y.S.; Han, Y.-K. HOTAIR: A Potential Metastatic, Drug-Resistant and Prognostic Regulator of Breast Cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.A.; Shah, N.; Wang, K.C.; Kim, J.; Horlings, H.M.; Wong, D.J.; Tsai, M.-C.; Hung, T.; Argani, P.; Rinn, J.L.; et al. Long Non-Coding RNA HOTAIR Reprograms Chromatin State to Promote Cancer Metastasis. Nature 2010, 464, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Jin, Y. LncRNA HOTAIR Promotes Cancer Stem-Like Cells Properties by Sponging MiR-34a to Activate the JAK2/STAT3 Pathway in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2021, 14, 1883–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collina, F.; Aquino, G.; Brogna, M.; Cipolletta, S.; Buonfanti, G.; De Laurentiis, M.; Di Bonito, M.; Cantile, M.; Botti, G. LncRNA HOTAIR Up-Regulation Is Strongly Related with Lymph Nodes Metastasis and LAR Subtype of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 2018–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matouk, I.J.; DeGroot, N.; Mezan, S.; Ayesh, S.; Abu-lail, R.; Hochberg, A.; Galun, E. The H19 Non-Coding RNA Is Essential for Human Tumor Growth. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, V.Y.; Chen, J.; Cheuk, I.W.-Y.; Siu, M.-T.; Ho, C.-W.; Wang, X.; Jin, H.; Kwong, A. Long Non-Coding RNA NEAT1 Confers Oncogenic Role in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer through Modulating Chemoresistance and Cancer Stemness. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, J.A.; Moradi Marjaneh, M.; Al-Ejeh, F.; Lim, Y.C.; Shi, W.; Sivakumaran, H.; Tropée, R.; Patch, A.-M.; Clark, M.B.; Bartonicek, N.; et al. Long Noncoding RNAs CUPID1 and CUPID2 Mediate Breast Cancer Risk at 11q13 by Modulating the Response to DNA Damage. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 101, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, L.S.; Andersen, M.S.; Stagsted, L.V.W.; Ebbesen, K.K.; Hansen, T.B.; Kjems, J. The Biogenesis, Biology and Characterization of Circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Dong, M.; Pan, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, S. Circular RNAs: A Novel Target among Non-coding RNAs with Potential Roles in Malignant Tumors (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 3463–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Bai, X.; Zeng, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Z. CircRNA-MiRNA-MRNA in Breast Cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta 2021, 523, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Liang, Y.; Sang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Du, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, W.; et al. CircHMCU Promotes Proliferation and Metastasis of Breast Cancer by Sponging the Let-7 Family. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 20, 518–533, Erratum in Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2021, 26, 1240, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2021.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.W.; Yang, W.; Li, X.; Awan, F.M.; Yang, Z.; Fang, L.; Lyu, J.; Li, F.; Peng, C.; Krylov, S.N.; et al. A Circular RNA Circ-DNMT1 Enhances Breast Cancer Progression by Activating Autophagy. Oncogene 2018, 37, 5829–5842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Chang, S.; Sang, Y.; Ding, P.; Wang, L.; Nan, X.; Xu, R.; Liu, F.; Gu, L.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Circular RNA CircCCDC85A Inhibits Breast Cancer Progression via Acting as a MiR-550a-5p Sponge to Enhance MOB1A Expression. Breast Cancer Res. 2022, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, H. Circular RNA VRK1 Correlates with Favourable Prognosis, Inhibits Cell Proliferation but Promotes Apoptosis in Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2020, 34, e22980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Zheng, M.; Wang, H. Circular RNA Hsa_circ_0072309 Inhibits Proliferation and Invasion of Breast Cancer Cells via Targeting MiR-492. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.K.D.M.; Arvinden, V.R.; Ramasamy, D.; Patel, K.; Meenakumari, B.; Ramanathan, P.; Sundersingh, S.; Sridevi, V.; Rajkumar, T.; Herceg, Z.; et al. Identification of Novel Dysregulated Circular RNAs in Early-stage Breast Cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 3912–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.; Chen, B.; Song, X.; Li, Y.; Liang, Y.; Han, D.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; et al. CircRNA_0025202 Regulates Tamoxifen Sensitivity and Tumor Progression via Regulating the MiR-182-5p/FOXO3a Axis in Breast Cancer. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 1638–1652, Erratum in Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 3525–3527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, W.; Xia, Z.; Liu, W.; Pan, G.; Ding, J.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Xie, X.; Jiang, D. Hsa_circ_0000199 Facilitates Chemo-Tolerance of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Interfering with MiR-206/613-Led PI3K/Akt/MTOR Signaling. Aging 2021, 13, 4522–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvari, P.; Sarvari, P.; Ramírez-Díaz, I.; Mahjoubi, F.; Rubio, K. Advances of Epigenetic Biomarkers and Epigenome Editing for Early Diagnosis in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.J.; Achinger-Kawecka, J.; Portman, N.; Clark, S.; Stirzaker, C.; Lim, E. Epigenetic Therapies and Biomarkers in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Rao, C.M. Epigenetics in Cancer: Fundamentals and Beyond. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 173, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, J.; Huo, Q.; Yang, F.; Xie, N. Perspectives on the Role of Histone Modification in Breast Cancer Progression and the Advanced Technological Tools to Study Epigenetic Determinants of Metastasis. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 603552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.; Venkatesh, D.; Kandasamy, T.; Ghosh, S.S. Epigenetic Modulations in Breast Cancer: An Emerging Paradigm in Therapeutic Implications. Front. Biosci. 2024, 29, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, M.; Bell, D.W.; Haber, D.A.; Li, E. DNA Methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b Are Essential for De Novo Methylation and Mammalian Development. Cell 1999, 99, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, C.; Yin, H.; Huang, J.; Yu, S.; Zhao, J.; Tang, Y.; Yu, M.; Lin, J.; Ding, L.; et al. The Mechanism of DNA Methylation and MiRNA in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Lou, J. DNA Methylation Analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1894, 181–227. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, W.A.; Aravind, L.; Rao, A. TETonic Shift: Biological Roles of TET Proteins in DNA Demethylation and Transcription. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshminarasimhan, R.; Liang, G. The Role of DNA Methylation in Cancer. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Vietri, M.; D’elia, G.; Benincasa, G.; Ferraro, G.; Caliendo, G.; Nicoletti, G.; Napoli, C. DNA Methylation and Breast Cancer: A Way Forward (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2021, 59, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajzendanc, K.; Domagała, P.; Hybiak, J.; Ryś, J.; Huzarski, T.; Szwiec, M.; Tomiczek-Szwiec, J.; Redelbach, W.; Sejda, A.; Gronwald, J.; et al. BRCA1 Promoter Methylation in Peripheral Blood Is Associated with the Risk of Triple-negative Breast Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Du, L.; Liu, X. Epigenetic Modifications in Breast Cancer: From Immune Escape Mechanisms to Therapeutic Target Discovery. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1584087, Erratum in Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1643911. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1643911 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosselin, K.; Durand, A.; Marsolier, J.; Poitou, A.; Marangoni, E.; Nemati, F.; Dahmani, A.; Lameiras, S.; Reyal, F.; Frenoy, O.; et al. High-Throughput Single-Cell ChIP-Seq Identifies Heterogeneity of Chromatin States in Breast Cancer. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, K.; Grabau, D.; Lövgren, K.; Aradottir, S.; Gruvberger-Saal, S.; Howlin, J.; Saal, L.H.; Ethier, S.P.; Bendahl, P.-O.; Stål, O.; et al. Global H3K27 Trimethylation and EZH2 Abundance in Breast Tumor Subtypes. Mol. Oncol. 2012, 6, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, M.A.; Hu, R.; Beck, A.H.; Collins, L.C.; Schnitt, S.J.; Tamimi, R.M.; Hazra, A. Association of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 Repressive Histone Marks with Breast Cancer Subtypes in the Nurses’ Health Study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 147, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsheikh, S.E.; Green, A.R.; Rakha, E.A.; Powe, D.G.; Ahmed, R.A.; Collins, H.M.; Soria, D.; Garibaldi, J.M.; Paish, C.E.; Ammar, A.A.; et al. Global Histone Modifications in Breast Cancer Correlate with Tumor Phenotypes, Prognostic Factors, and Patient Outcome. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 3802–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, L.; Kolben, T.; Meister, S.; Kolben, T.M.; Schmoeckel, E.; Mayr, D.; Mahner, S.; Jeschke, U.; Ditsch, N.; Beyer, S. Expression of H3K4me3 and H3K9ac in Breast Cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 146, 2017–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrissou, M.; Boisnier, T.; Sanches, A.; Khoufaf, F.Z.H.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Bignon, Y.-J.; Bernard-Gallon, D. TIP60/P400/H4K12ac Plays a Role as a Heterochromatin Back-up Skeleton in Breast Cancer. Cancer Genom.-Proteom. 2020, 17, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hałasa, M.; Wawruszak, A.; Przybyszewska, A.; Jaruga, A.; Guz, M.; Kałafut, J.; Stepulak, A.; Cybulski, M. H3K18Ac as a Marker of Cancer Progression and Potential Target of Anti-Cancer Therapy. Cells 2019, 8, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denkert, C.; von Minckwitz, G.; Darb-Esfahani, S.; Lederer, B.; Heppner, B.I.; Weber, K.E.; Budczies, J.; Huober, J.; Klauschen, F.; Furlanetto, J.; et al. Tumour-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Prognosis in Different Subtypes of Breast Cancer: A Pooled Analysis of 3771 Patients Treated with Neoadjuvant Therapy. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.H.; Li, C.X.; Liu, M.; Jiang, J.Y. Predictive and Prognostic Role of Tumour-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Breast Cancer Patients with Different Molecular Subtypes: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.; Labarriere, N. PD-1 Expression on Tumor-Specific T Cells: Friend or Foe for Immunotherapy? Oncoimmunology 2017, 7, e1364828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranic, S.; Cyprian, F.S.; Gatalica, Z.; Palazzo, J. PD-L1 Status in Breast Cancer: Current View and Perspectives. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 72, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debien, V.; De Caluwé, A.; Wang, X.; Piccart-Gebhart, M.; Tuohy, V.K.; Romano, E.; Buisseret, L. Immunotherapy in Breast Cancer: An Overview of Current Strategies and Perspectives. NPJ Breast Cancer 2023, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, X. Classification of Triple-Negative Breast Cancers Based on Immunogenomic Profiling. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan, D.; McArdle, S.E.B. Immune Landscape of Breast Cancers. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erber, R.; Hartmann, A. Understanding PD-L1 Testing in Breast Cancer: A Practical Approach. Breast Care 2020, 15, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marletta, S.; Fusco, N.; Munari, E.; Luchini, C.; Cimadamore, A.; Brunelli, M.; Querzoli, G.; Martini, M.; Vigliar, E.; Colombari, R.; et al. Atlas of PD-L1 for Pathologists: Indications, Scores, Diagnostic Platforms and Reporting Systems. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bairi, K.; Haynes, H.R.; Blackley, E.; Fineberg, S.; Shear, J.; Turner, S.; de Freitas, J.R.; Sur, D.; Amendola, L.C.; Gharib, M.; et al. The Tale of TILs in Breast Cancer: A Report from The International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group. NPJ Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, B.M.; Verrill, C. Clinical Significance of Tumour-Infiltrating B Lymphocytes (TIL-Bs) in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Literature Review. Cancers 2023, 15, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado, R.; Denkert, C.; Demaria, S.; Sirtaine, N.; Klauschen, F.; Pruneri, G.; Wienert, S.; Van den Eynden, G.; Baehner, F.L.; Penault-Llorca, F.; et al. The Evaluation of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs) in Breast Cancer: Recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanton, S.E.; Adams, S.; Disis, M.L. Variation in the Incidence and Magnitude of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Breast Cancer Subtypes: A Systematic Review. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1354–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, G.; De Angelis, C.; Licata, L.; Gianni, L. Treatment Landscape of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer—Expanded Options, Evolving Needs. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, R.; Chow, L.Q.M.; Dees, E.C.; Berger, R.; Gupta, S.; Geva, R.; Pusztai, L.; Pathiraja, K.; Aktan, G.; Cheng, J.D.; et al. Pembrolizumab in Patients With Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2460–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini Silveira, A.; Bidard, F.C.; Tanguy, M.L.; Girard, E.; Trédan, O.; Dubot, C.; Jacot, W.; Goncalves, A.; Debled, M.; Levy, C.; et al. Multimodal Liquid Biopsy for Early Monitoring and Outcome Prediction of Chemotherapy in Metastatic Breast Cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantel, K.; Alix-Panabières, C. Liquid Biopsy and Minimal Residual Disease—Latest Advances and Implications for Cure. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.J.; Garrido-Navas, M.C.; Mochon, J.J.D.; Cristofanilli, M.; Gil-Bazo, I.; Pauwels, P.; Malapelle, U.; Russo, A.; Lorente, J.A.; Ruiz-Rodriguez, A.J.; et al. Precision Prevention and Cancer Interception: The New Challenges of Liquid Biopsy. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1635–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilgour, E.; Rothwell, D.G.; Brady, G.; Dive, C. Liquid Biopsy-Based Biomarkers of Treatment Response and Resistance. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, M.; Ros, M.; Saltel, F. A Complex and Evolutive Character: Two Face Aspects of ECM in Tumor Progression. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Yu, X.; Zheng, F.; Gu, X.; Huang, Q.Q.; Qin, K.; Hu, Y.; Liu, B.; Xu, T.; Zhang, T.; et al. Advancements in Liquid Biopsy for Breast Cancer: Molecular Biomarkers and Clinical Applications. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2025, 139, 102979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Neiswender, J.; Fang, B.; Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X. Value of Circulating Cell-Free DNA Analysis as a Diagnostic Tool for Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 26625–26636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.H.; Li, L.H.; Hua, D. Quantitative Analysis of Plasma Circulating DNA at Diagnosis and during Follow-up of Breast Cancer Patients. Cancer Lett. 2006, 243, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, I.B.; Hench, J.; Tolnay, M. Liquid Biopsy in Clinical Management of Breast, Lung, and Colorectal Cancer. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, S.; Bai, F. Molecular Characterization of Circulating Tumor Cells—From Bench to Bedside. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 75, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalik, A.; Kowalewska, M.; Góźdź, S. Current Approaches for Avoiding the Limitations of Circulating Tumor Cells Detection Methods—Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Solid Tumors. Transl. Res. 2017, 185, 58–84.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadaki, M.A.; Stoupis, G.; Theodoropoulos, P.A.; Mavroudis, D.; Georgoulias, V.; Agelaki, S. Circulating Tumor Cells with Stemness and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Features Are Chemoresistant and Predictive of Poor Outcome in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Riethdorf, S.; Wu, G.; Wang, T.; Yang, K.; Peng, G.; Liu, J.; Pantel, K. Meta-Analysis of the Prognostic Value of Circulating Tumor Cells in Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 5701–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janni, W.J.; Rack, B.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M.; Pierga, J.Y.; Taran, F.A.; Fehm, T.; Hall, C.; De Groot, M.R.; Bidard, F.C.; Friedl, T.W.P.; et al. Pooled Analysis of the Prognostic Relevance of Circulating Tumor Cells in Primary Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 2583–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, G.T.; Cristofanilli, M.; Ellis, M.J.; Stopeck, A.; Borden, E.; Miller, M.C.; Matera, J.; Repollet, M.; Doyle, G.V.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cells versus Imaging—Predicting Overall Survival in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 6403–6409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miricescu, D.; Totan, A.; Stanescu-Spinu, I.-I.; Badoiu, S.C.; Stefani, C.; Greabu, M. PI3K/AKT/MTOR Signaling Pathway in Breast Cancer: From Molecular Landscape to Clinical Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braglia, L.; Zavatti, M.; Vinceti, M.; Martelli, A.M.; Marmiroli, S. Deregulated PTEN/PI3K/AKT/MTOR Signaling in Prostate Cancer: Still a Potential Druggable Target? Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2020, 1867, 118731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, P.; Ramisetty, S.; Nair, M.; Kulkarni, P.; Horne, D.; Salgia, R.; Singhal, S.S. Strategic Advancements in Targeting the PI3K/AKT/MTOR Pathway for Breast Cancer Therapy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 236, 116850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Barik, D.; Lawrie, K.; Mohapatra, I.; Prasad, S.; Naqvi, A.R.; Singh, A.; Singh, G. Unveiling Novel Avenues in MTOR-Targeted Therapeutics: Advancements in Glioblastoma Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, I.M.; Okines, A.F.C. Resistance to Targeted Inhibitors of the PI3K/AKT/MTOR Pathway in Advanced Oestrogen-Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, T.H.; Roman Ortiz, N.I.; Ufondu, C.A.; Lee, S.-J.; Ostrander, J.H. Emerging Mechanisms of Therapy Resistance in Metastatic ER+ Breast Cancer. Endocrinology 2025, 166, bqaf127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pu, W.; Zheng, Q.; Ai, M.; Chen, S.; Peng, Y. Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) in Cancer Therapy. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafari, J.; Fernández-Lodeiro, J.; Santos, H.M.; Lorenzo, J.; Rodriguez-Calado, S.; Bértolo, E.; Capelo-Martínez, J.L.; Lodeiro, C. Study and Preparation of Multifunctional Poly(L-Lysine)@Hyaluronic Acid Nanopolyplexes for the Effective Delivery of Tumor Suppressive MiR-34a into Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Materials 2020, 13, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsarraf, Z.; Nori, A.; Oraibi, A.; Al-Hussaniy, H.; Jabbar, A. BIBR1591 induces apoptosis in breast cancer cell line and increases expression of DAPK1, AND NR4A3. Cancer 2024, 9, 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Nagahashi, M.; Komatsu, M.; Urano, S.; Kuroiwa, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Morimoto, K.; Pradipta, A.R.; Tanaka, K.; Miyoshi, Y. An Acrolein-Based Drug Delivery System Enables Tumor-Specific Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Targeting in Breast Cancer without Lymphocytopenia. Cancer Res. Commun. 2025, 5, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhou, H.; Tan, L.; Siu, K.T.H.; Guan, X.-Y. Exploring Treatment Options in Cancer: Tumor Treatment Strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Miao, J.; Pusztai, L.; Goetz, M.P.; Rastogi, P.; Ganz, P.A.; Mamounas, E.P.; Paik, S.; Bandos, H.; Razaq, W.; et al. Phase III Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Endocrine Therapy ± 1 Year of Everolimus in Patients With High-Risk, Hormone Receptor–Positive, Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 3012–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.H.; Obeid, R.A.; Fadhil, A.A.; Amir, A.A.; Adhab, Z.H.; Jabouri, E.A.; Ahmad, I.; Alshahrani, M.Y. BTLA and HVEM: Emerging Players in the Tumor Microenvironment and Cancer Progression. Cytokine 2023, 172, 156412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, J.; Kim, S.-B.; Chung, W.-P.; Im, S.-A.; Park, Y.H.; Hegg, R.; Kim, M.H.; Tseng, L.-M.; Petry, V.; Chung, C.-F.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan versus Trastuzumab Emtansine for Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabeti Touchaei, A.; Vahidi, S. MicroRNAs as Regulators of Immune Checkpoints in Cancer Immunotherapy: Targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 Pathways. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Spiegel, S. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Signaling: A Novel Target for Simultaneous Adjuvant Treatment of Triple Negative Breast Cancer and Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2020, 75, 100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tülüce, Y.; Köstekci, S.; Karakuş, F.; Keleş, A.Y.; Tunçyürekli, M. Investigation the Immunotherapeutic Potential of MiR-4477a Targeting PD-1/PD-L1 in Breast Cancer Cell Line Using a CD8+ Co-Culture Model. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Na, L.; Hu, E.-X.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.-G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.-B. Clinical Diagnostic Value of Circ-ARHGER28 for Breast Cancer and Its Effect on MCF 7 Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis. Anticancer Res. 2024, 44, 2877–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, M.; Besta, S.; Betrán, A.L.; Nia, R.S.; Xie, X.; Gu, X.; Shu, Q.; Giamas, G. CRISPR Screening Approaches in Breast Cancer Research. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2025, 44, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritika; Rani, S.; Malviya, R.; Rajput, S.; Belagodu Sridhar, S.; Kaushik, D. Understanding the Prospective of Gene Therapy for the Treatment of Breast Cancer. Rev. Senol. Patol. Mamar. 2025, 38, 100683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unidirwade, D.S.; Lade, S.N.; Umekar, M.J.; Burle, S.S.; Rangari, S.W. Innovative Theranostic Potential of Graphene Quantum Dot Nanocomposites in Breast Cancer. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, I.J.; Ovejero-Paredes, K.; Méndez-Arriaga, J.M.; Pizúrová, N.; Filice, M.; Zajíčková, L.; Prashar, S.; Gómez-Ruiz, S. Organotin(IV)-Decorated Graphene Quantum Dots as Dual Platform for Molecular Imaging and Treatment of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202301845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esgandari, K.; Mohammadian, M.; Zohdiaghdam, R.; Rastin, S.J.; Alidadi, S.; Behrouzkia, Z. Combined Treatment with Silver Graphene Quantum Dot, Radiation, and 17-AAG Induces Anticancer Effects in Breast Cancer Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 2817–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohajeri, S.; Yaghoubi, H.; Bourang, S.; Noruzpour, M. Multifunctional Magnetic Nanocapsules for Dual Delivery of SiRNA and Chemotherapy to MCF-7 Cells (Breast Cancer Cells). Naunyn-Schmiedeberg′s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 17957–17979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugo, H.S.; Lacouture, M.E.; Goncalves, M.D.; Masharani, U.; Aapro, M.S.; O’Shaughnessy, J.A. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Optimizing Care of Patients Treated with Alpelisib. Breast 2022, 61, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darapu, H.; McKnight, M. Capivasertib-Induced Refractory Hyperglycemia in a Nondiabetic Patient with Metastatic Breast Cancer. AACE Endocrinol. Diabetes 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolinsky, M.P.; Rescigno, P.; Bianchini, D.; Zafeiriou, Z.; Mehra, N.; Mateo, J.; Michalarea, V.; Riisnaes, R.; Crespo, M.; Figueiredo, I.; et al. A Phase I Dose-Escalation Study of Enzalutamide in Combination with the AKT Inhibitor AZD5363 (Capivasertib) in Patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.; Xu, X. Target of Rapamycin (TOR)–Based Therapy for Cardiomyopathy: Evidence From Zebrafish and Human Studies. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2012, 22, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnikrishnan, A.; Deepa, S.S.; Herd, H.R.; Richardson, A. Extension of Life Span in Laboratory Mice. In Conn’s Handbook of Models for Human Aging; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 245–270. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, L.; Zhao, D.-S.; Zhao, P.; Yan, P. Overview of Research into MTOR Inhibitors. Molecules 2022, 27, 5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullschleger, S.; Loewith, R.; Hall, M.N. TOR Signaling in Growth and Metabolism. Cell 2006, 124, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, A.; Aghajanian, C.; Raymond, E.; Olmos, D.; Schwartz, G.; Oelmann, E.; Grinsted, L.; Burke, W.; Taylor, R.; Kaye, S.; et al. Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of AZD8055 in Advanced Solid Tumours and Lymphoma. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Campo, J.M.; Birrer, M.; Davis, C.; Fujiwara, K.; Gollerkeri, A.; Gore, M.; Houk, B.; Lau, S.; Poveda, A.; González-Martín, A.; et al. A Randomized Phase II Non-Comparative Study of PF-04691502 and Gedatolisib (PF-05212384) in Patients with Recurrent Endometrial Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 142, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylaź, M.; Kaczmarska, A.; Pajor, D.; Hryniewicki, M.; Gil, D.; Dulińska-Litewka, J. Exploring the Role of PI3K/AKT/MTOR Inhibitors in Hormone-Related Cancers: A Focus on Breast and Prostate Cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Xing, W.; Yu, H.; Zhang, W.; Si, T. ABCB1 and ABCG2 Restricts the Efficacy of Gedatolisib (PF-05212384), a PI3K Inhibitor in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, L.E.; Kong, C.K.; Yap, W.-H.; Siva, S.P.; Gan, S.H.; Siew, W.S.; Ming, L.C.; Lai-Foenander, A.S.; Chang, S.K.; Lee, W.-L.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine: Key Therapeutic Advances and Emerging Nanotechnological Landscape for Cancer Mitigation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 386, 110750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahim, R.; Strobl, J.S. Hydroxychloroquine, Chloroquine, and All-Trans Retinoic Acid Regulate Growth, Survival, and Histone Acetylation in Breast Cancer Cells. Anticancer Drugs 2009, 20, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchook, G.; Infante, J.; Arkenau, H.-T.; Patel, M.R.; Dean, E.; Borazanci, E.; Brenner, A.; Cook, N.; Lopez, J.; Pant, S.; et al. First-in-Human Study of the Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of First-in-Class Fatty Acid Synthase Inhibitor TVB-2640 Alone and with a Taxane in Advanced Tumors. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 34, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, W.; Diaz Duque, A.E.; Michalek, J.; Konkel, B.; Caflisch, L.; Chen, Y.; Pathuri, S.C.; Madhusudanannair-Kunnuparampil, V.; Floyd, J.; Brenner, A. Phase II Investigation of TVB-2640 (Denifanstat) with Bevacizumab in Patients with First Relapse High-Grade Astrocytoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 2419–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Bedossa, P.; Grimmer, K.; Kemble, G.; Bruno Martins, E.; McCulloch, W.; O’Farrell, M.; Tsai, W.-W.; Cobiella, J.; Lawitz, E.; et al. Denifanstat for the Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis: A Multicentre, Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2b Trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, H.A.; Bao, L.; Cheng, X.; Qin, Z.; Liu, C.-J.; Heth, J.A.; Udager, A.M.; Soellner, M.B.; Merajver, S.D.; Morikawa, A.; et al. Targeting Fatty Acid Synthase in Preclinical Models of TNBC Brain Metastases Synergizes with SN-38 and Impairs Invasion. NPJ Breast Cancer 2024, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campone, M.; De Laurentiis, M.; Jhaveri, K.; Hu, X.; Ladoire, S.; Patsouris, A.; Zamagni, C.; Cui, J.; Cazzaniga, M.; Cil, T.; et al. Vepdegestrant, a PROTAC Estrogen Receptor Degrader, in Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gough, S.M.; Flanagan, J.J.; Teh, J.; Andreoli, M.; Rousseau, E.; Pannone, M.; Bookbinder, M.; Willard, R.; Davenport, K.; Bortolon, E.; et al. Oral Estrogen Receptor PROTAC Vepdegestrant (ARV-471) Is Highly Efficacious as Monotherapy and in Combination with CDK4/6 or PI3K/MTOR Pathway Inhibitors in Preclinical ER+ Breast Cancer Models. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 3549–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.F.R.; Shao, Z.; Noguchi, S.; Bondarenko, I.; Panasci, L.; Singh, S.; Subramaniam, S.; Ellis, M.J. Fulvestrant Versus Anastrozole in Endocrine Therapy–Naïve Women With Hormone Receptor–Positive Advanced Breast Cancer: Final Overall Survival in the Phase III FALCON Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 1539–1545, Erratum in J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 1045 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO-25-00116.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, R.W. The History and Mechanism of Action of Fulvestrant. Clin. Breast Cancer 2005, 6, S5–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri, K.L.; Neven, P.; Casalnuovo, M.L.; Kim, S.-B.; Tokunaga, E.; Aftimos, P.; Saura, C.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Harbeck, N.; Carey, L.A.; et al. Imlunestrant with or without Abemaciclib in Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Karmalawy, A.A.; Mousa, M.H.A.; Sharaky, M.; Mourad, M.A.E.; El-Dessouki, A.M.; Hamouda, A.O.; Alnajjar, R.; Ayed, A.A.; Shaldam, M.A.; Tawfik, H.O. Lead Optimization of BIBR1591 To Improve Its Telomerase Inhibitory Activity: Design and Synthesis of Novel Four Chemical Series with In Silico, In Vitro, and In Vivo Preclinical Assessments. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 492–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboushanab, A.R.; El-Moslemany, R.M.; El-Kamel, A.H.; Mehanna, R.A.; Bakr, B.A.; Ashour, A.A. Targeted Fisetin-Encapsulated β-Cyclodextrin Nanosponges for Breast Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, N.; Yamada, S.; Yanagida, S.; Ono, A.; Kanda, Y. FTY720 Inhibits Expansion of Breast Cancer Stem Cells via PP2A Activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, W.-P.; Huang, W.-L.; Liao, W.-A.; Hung, C.-H.; Chiang, C.-W.; Cheung, C.H.A.; Su, W.-C. FTY720 in Resistant Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasaki, T.; Hagihara, K.; Satoh, R.; Sugiura, R. More than Just an Immunosuppressant: The Emerging Role of FTY720 as a Novel Inducer of ROS and Apoptosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 4397159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health Pembrolizumab (Keytruda). CADTH Reimbursement Review: Therapeutic Area: Triple-Negative Breast Cancer; Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Ramesh, A.; Gusev, Y.; Bhuvaneshwar, K.; Giaccone, G. Molecular Predictors of Response to Pembrolizumab in Thymic Carcinoma. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleem, A.; Shah, H. Atezolizumab. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hamidi, H.; Senbabaoglu, Y.; Beig, N.; Roels, J.; Manuel, C.; Guan, X.; Koeppen, H.; Assaf, Z.J.; Nabet, B.Y.; Waddell, A.; et al. Molecular Heterogeneity in Urothelial Carcinoma and Determinants of Clinical Benefit to PD-L1 Blockade. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 2098–2112.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sledge, G.; Xiu, J.; Mahtani, R.L.; Sandoval Leon, A.C.; Oberley, M.J.; Radovich, M.; Spetzler, D. Abstract PS13-09: Mechanisms of Resistance to Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Breast Cancer Elucidated by Multi-Omic Molecular Profiling. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, PS13-09-PS13-09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolaney, S.M.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Barroso-Sousa, R.; Park, Y.H.; Rimawi, M.F.; Saura, C.; Schneeweiss, A.; Toi, M.; Chae, Y.S.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan plus Pertuzumab for HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]