Comparative Thermal Tolerance and Tissue-Specific Responses Patterns to Gradual Heat Stress in Reciprocal Cross Hybrids of Acipenser baerii and A. schrenckii

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

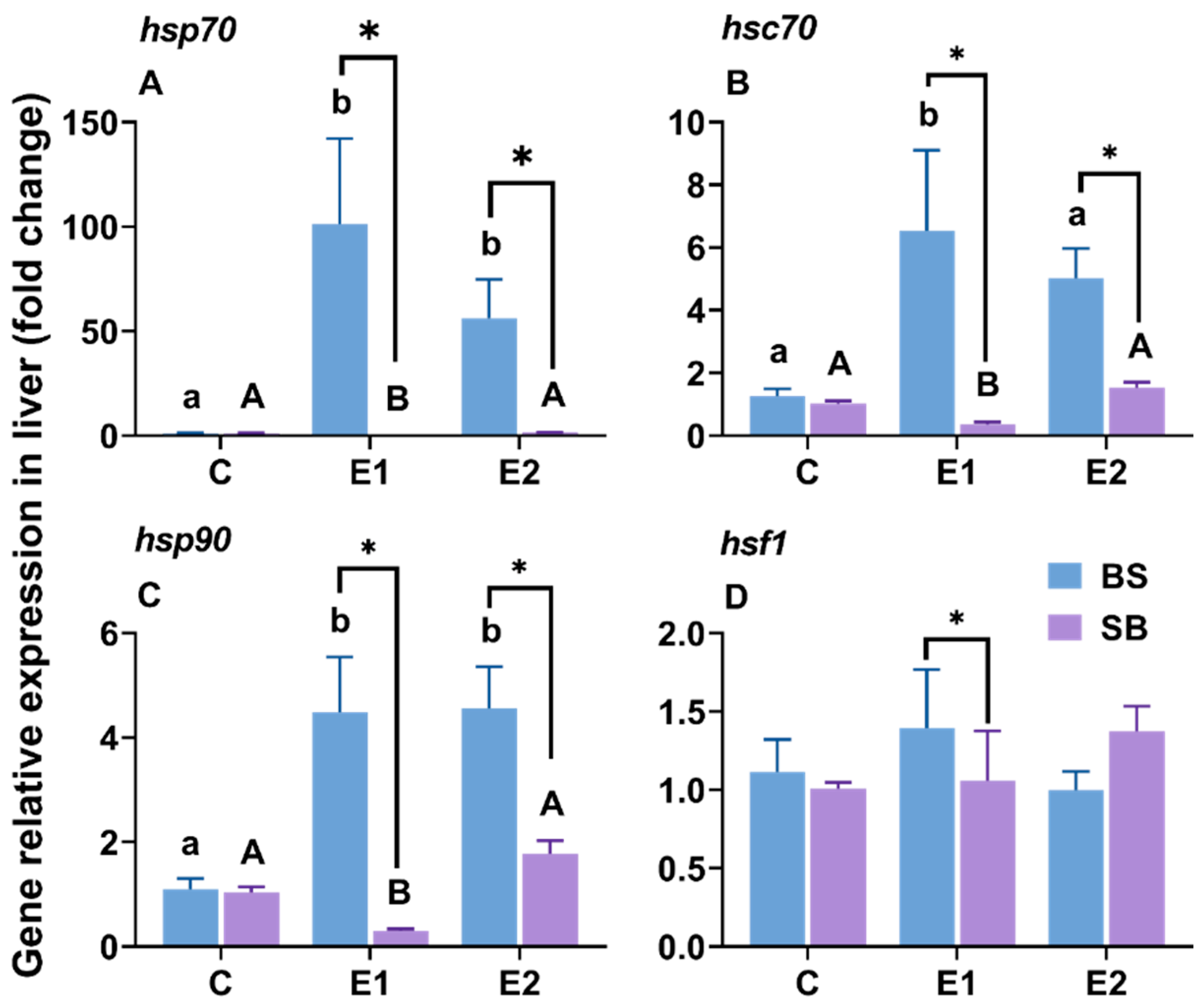

2.1. Changes in Hsp-Related Gene Expression in the Liver Under Slow Heat Stress

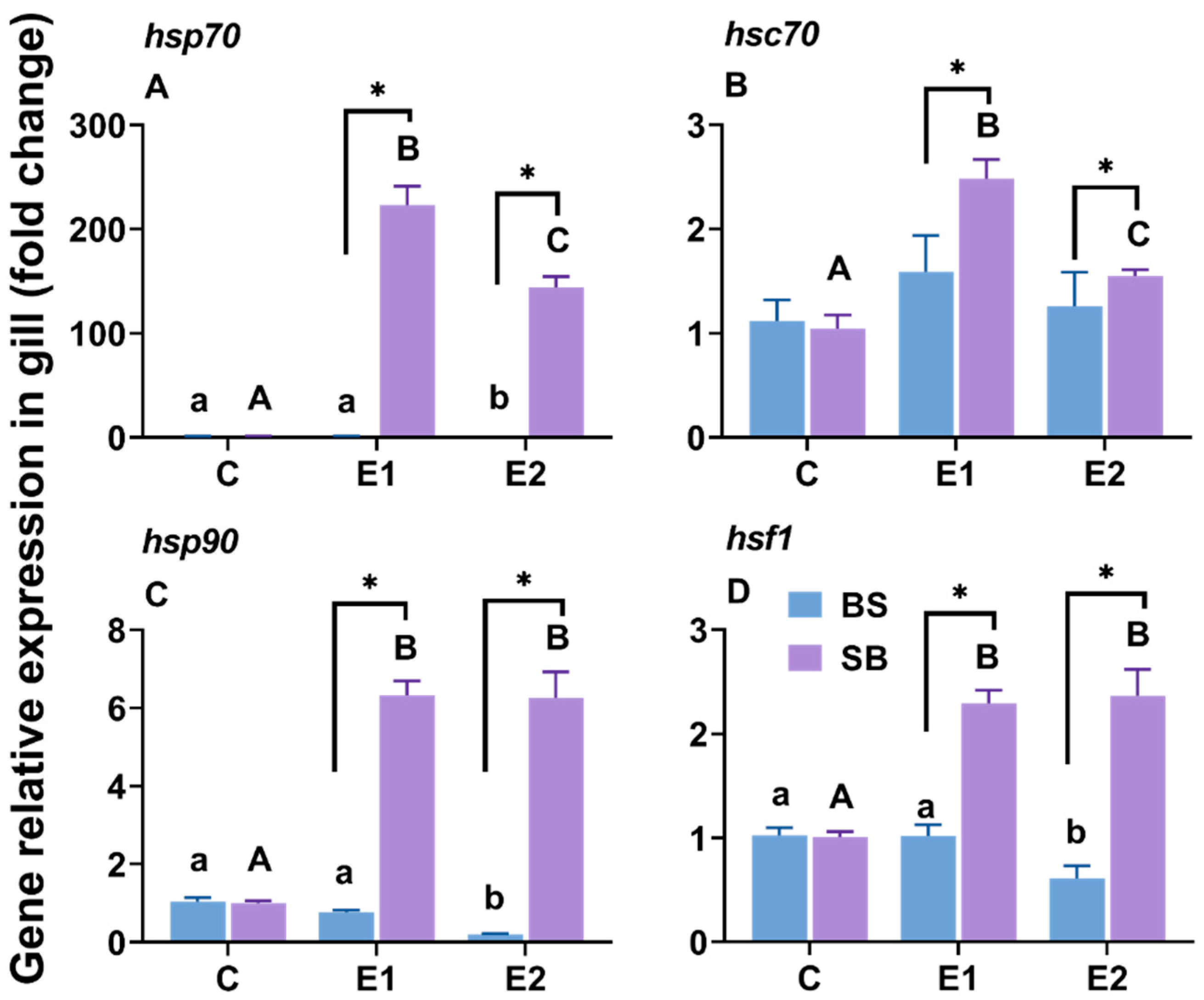

2.2. Changes in Hsp-Related Gene Expression in the Gill Under Slow Heat Stress

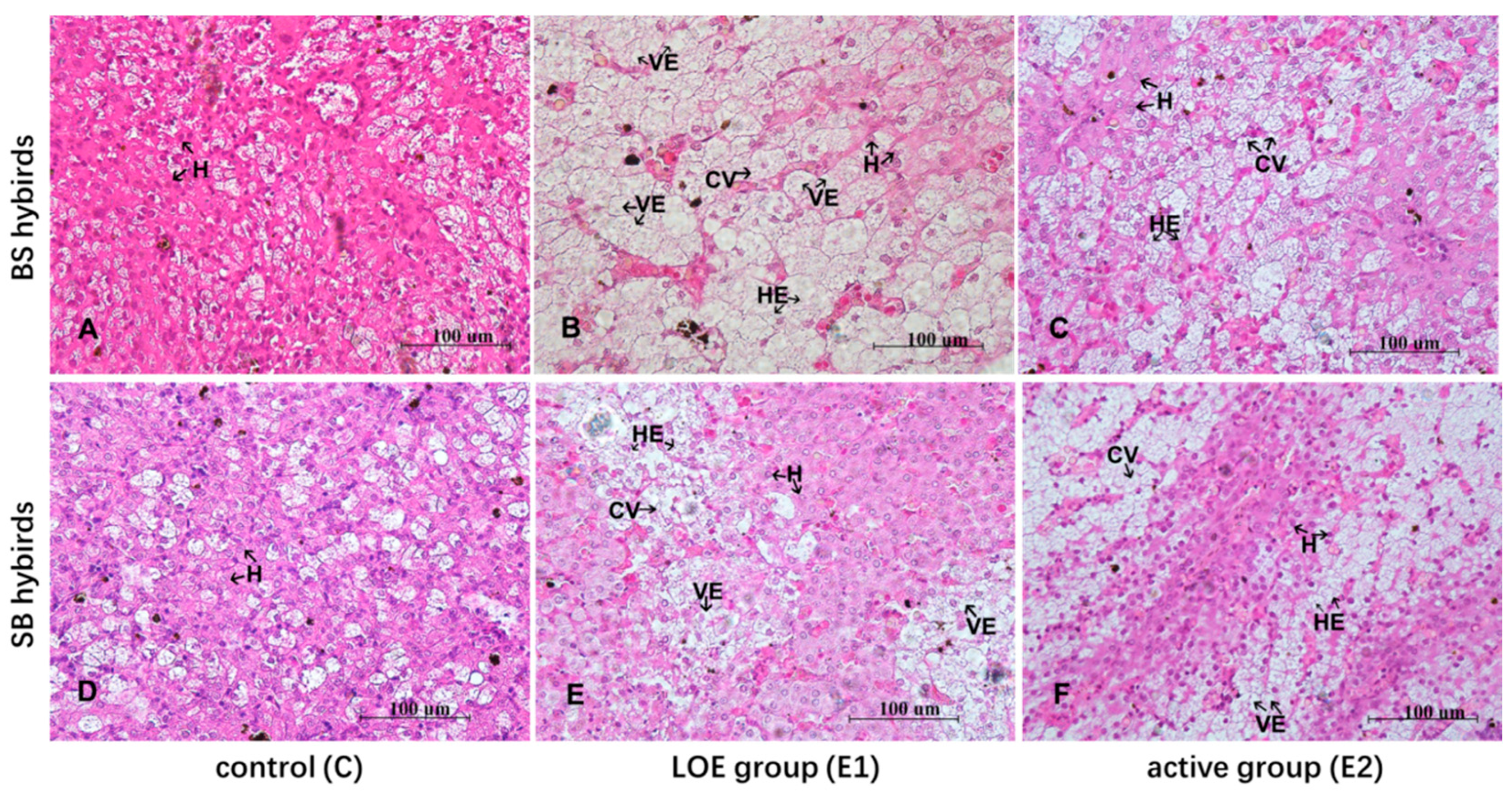

2.3. Histological Changes in Liver Under Slow Heat Stress

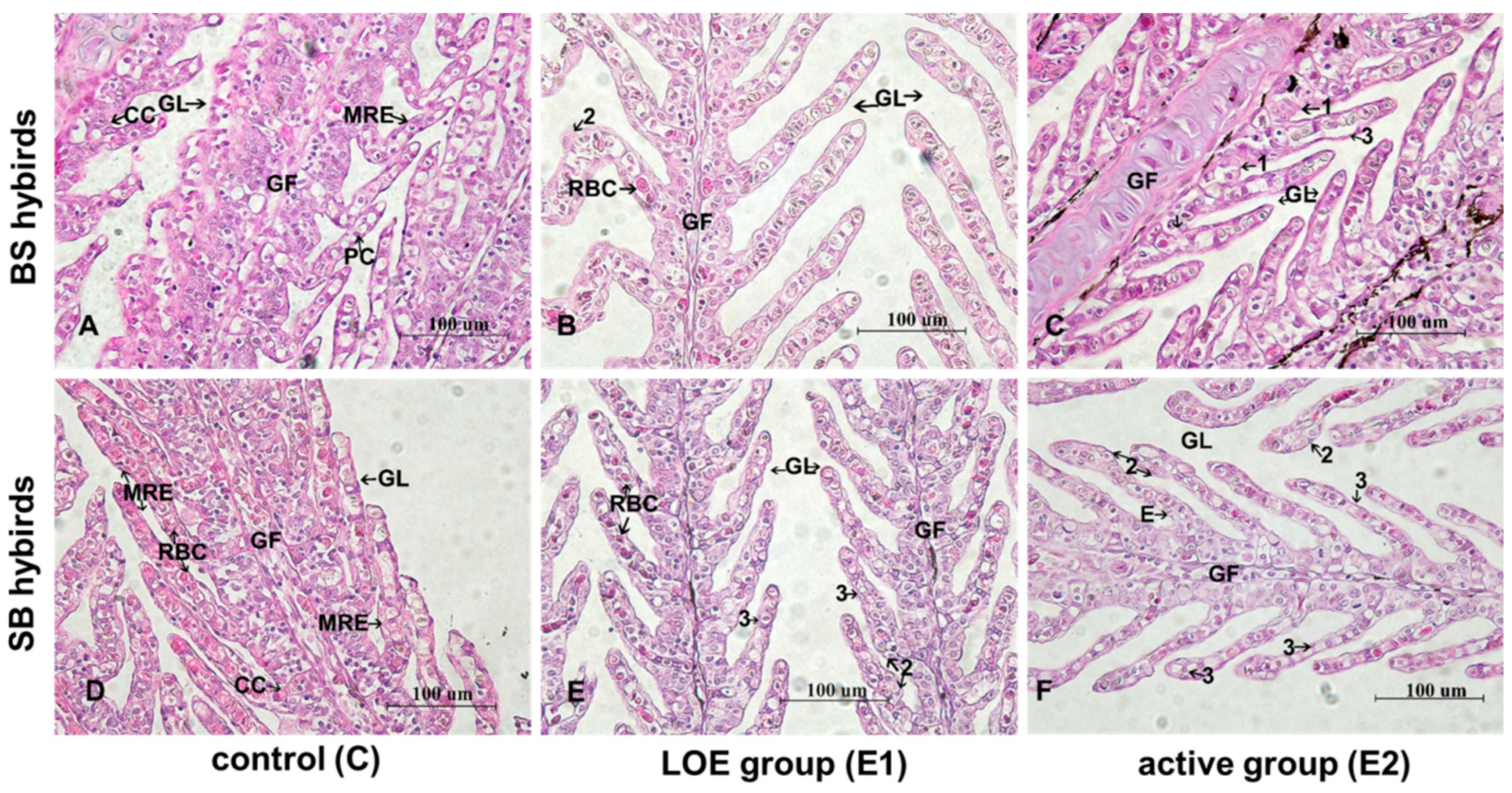

2.4. Histological Changes in Gill Under Slow Heat Stress

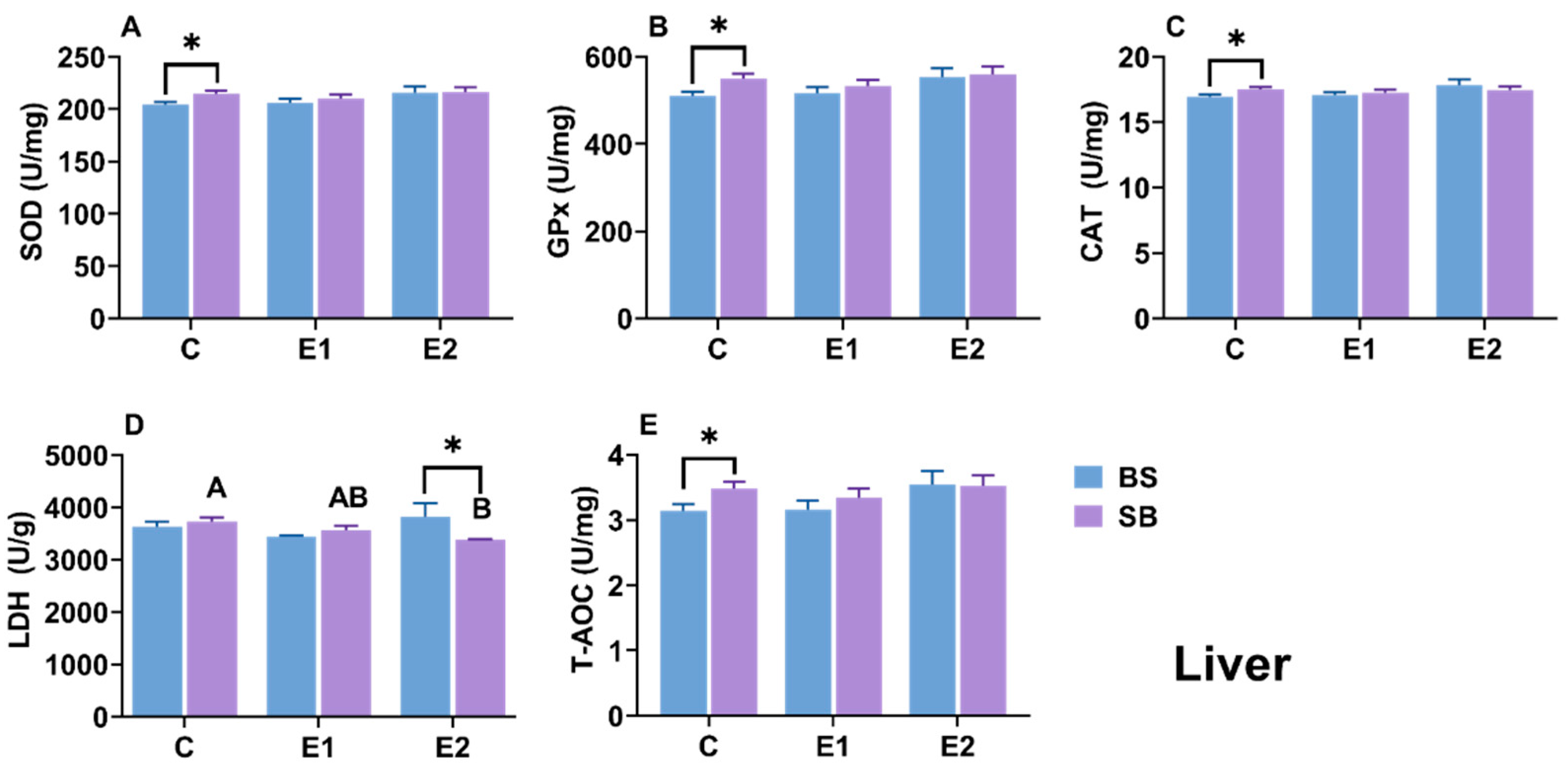

2.5. Changes in Biochemical Parameters in Liver

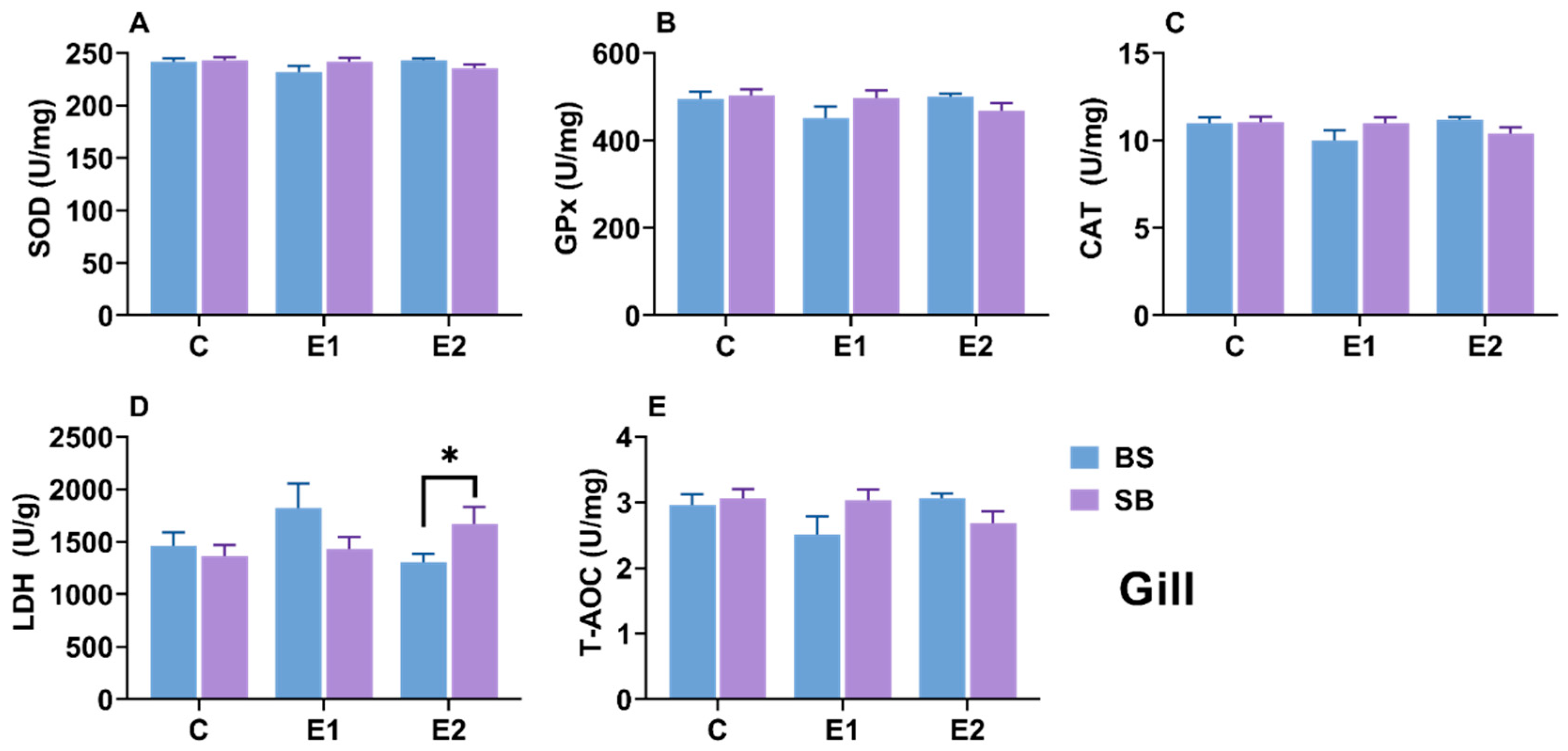

2.6. Changes in Biochemical Parameters in Gill

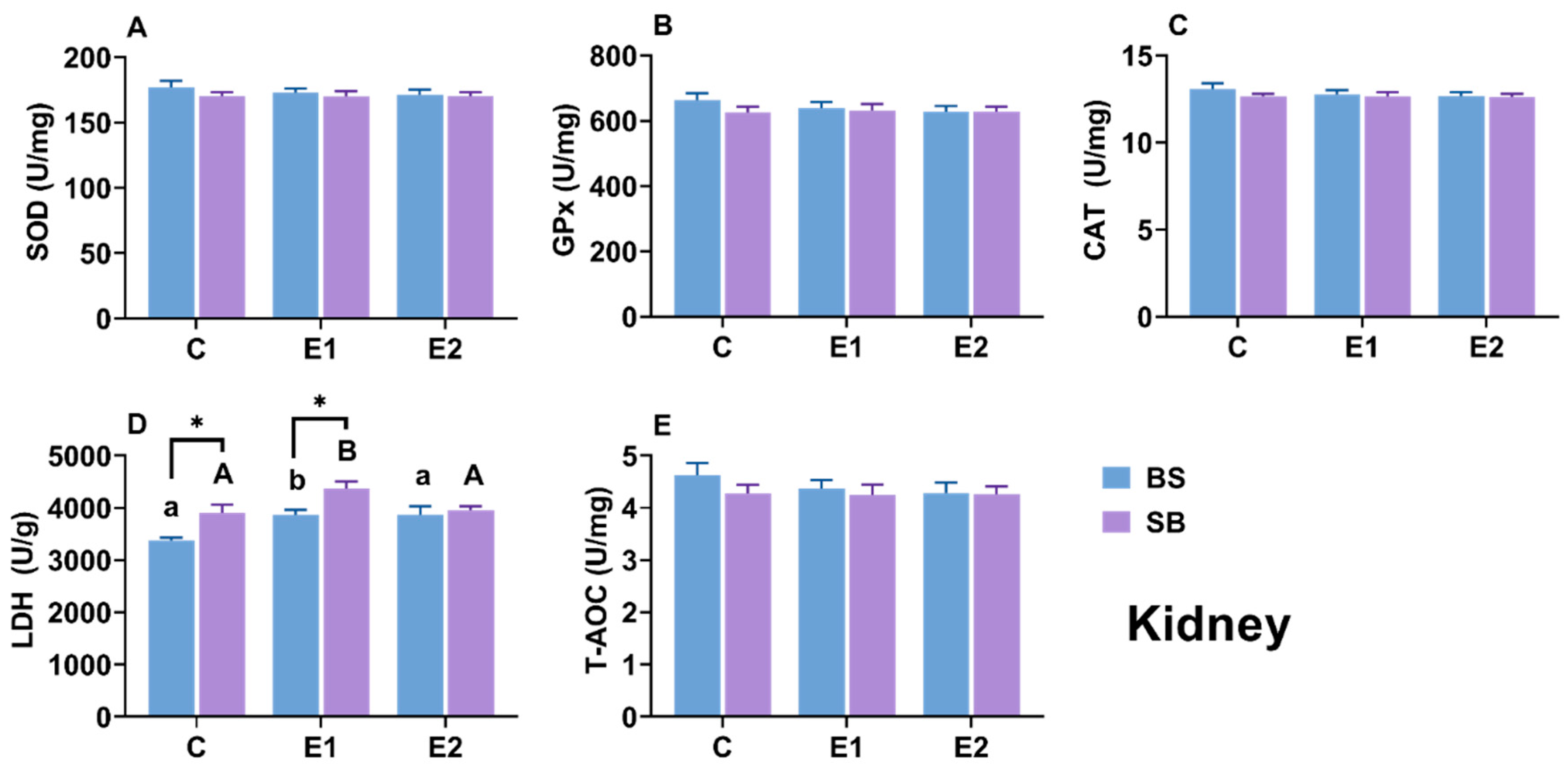

2.7. Changes in Biochemical Parameters in Kidney

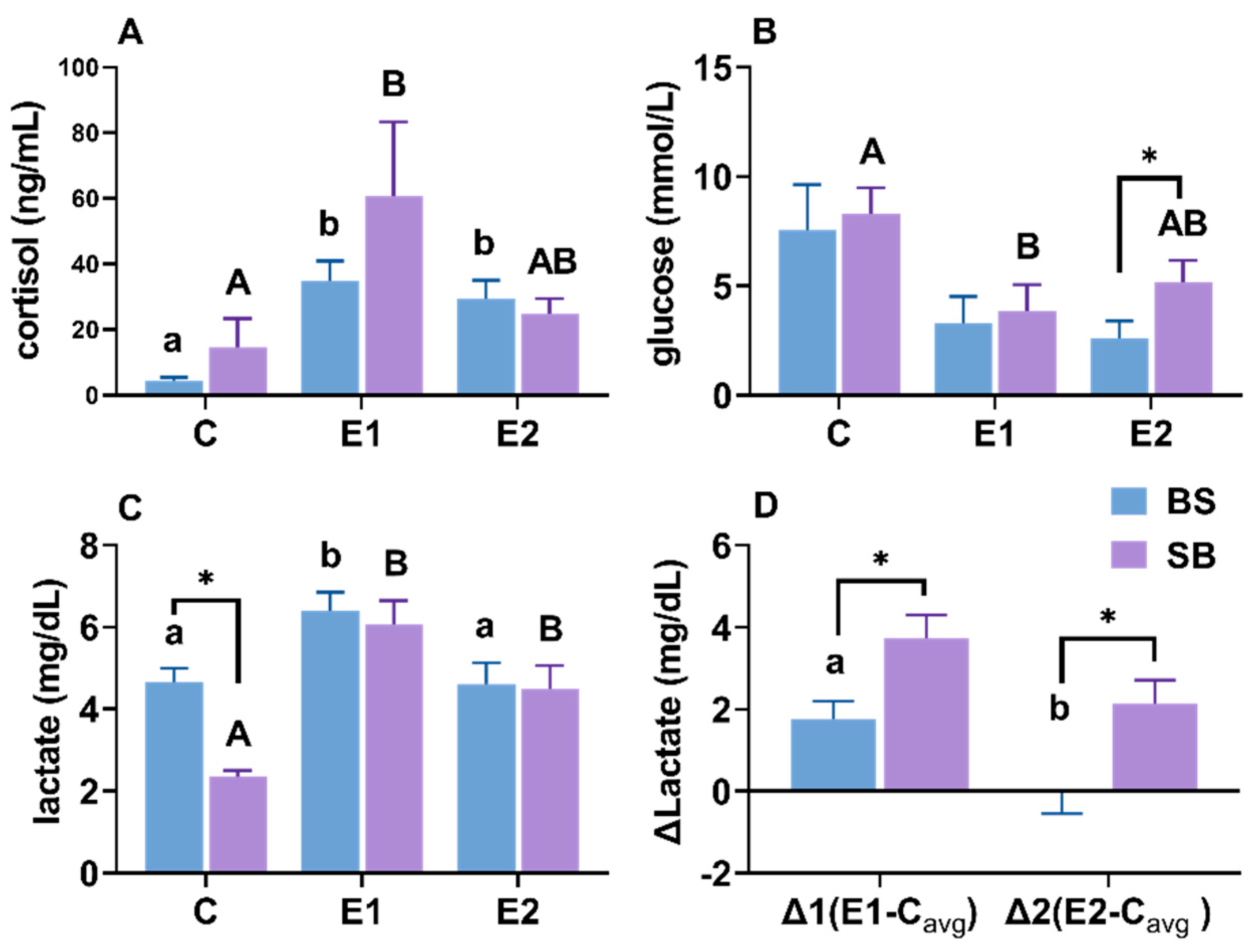

2.8. Changes in Cortisol, Glucose and Lactate Content in Serum

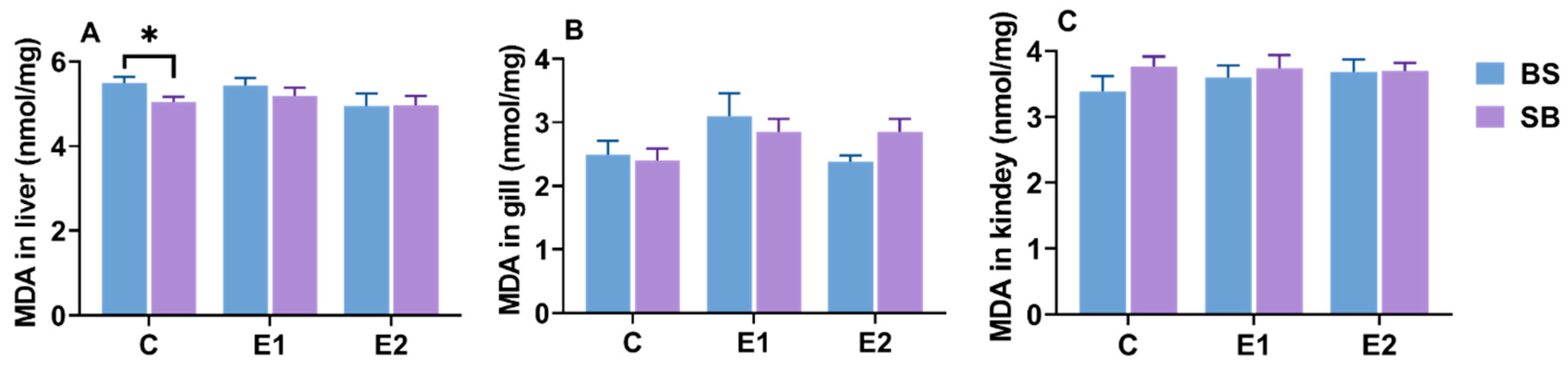

2.9. Changes in Hepatic, Branchial, and Renal MDA Content

3. Discussion

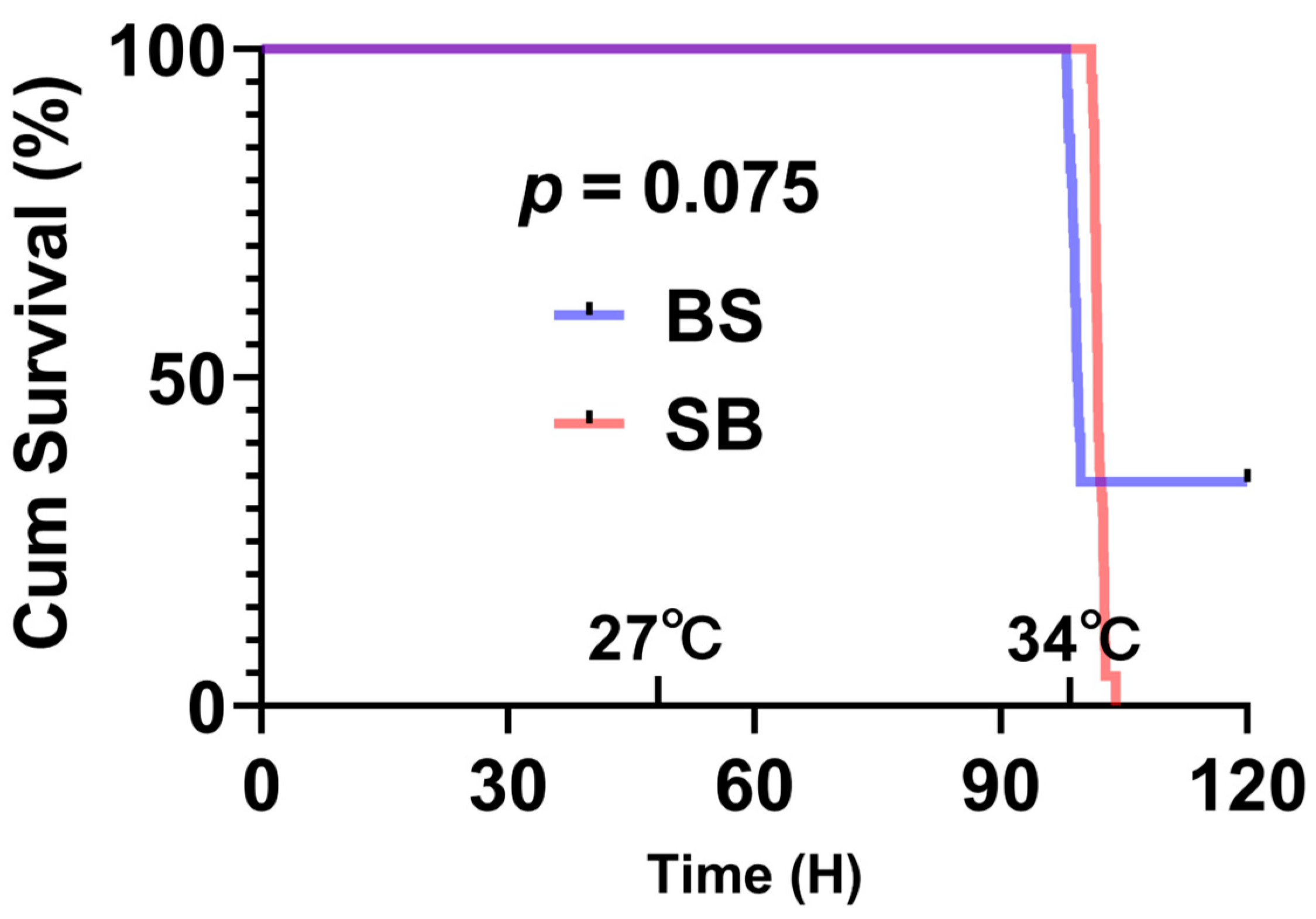

3.1. Thermal Tolerance of Reciprocal Hybrid Sturgeon

3.2. Organ-Specific Antioxidant and Metabolic Responses

3.3. Heat Shock Protein Gene Expression

3.4. Hormonal and Energy Metabolism Changes

3.5. Implications for Aquaculture and Future Research

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Fish

4.2. Slow Heat Stress Exposure and Sampling

4.3. RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

4.4. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

4.5. Histological Procedure

4.6. Liver, Gill, Kidney, and Serum Biochemical Analyses

4.7. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Billard, R.; Lecointre, G. Biology and conservation of sturgeon and paddlefish. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2001, 10, 355–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). IPCC Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lassalle, G.; Crouzet, P.; Gessner, J.; Rochard, E. Global warming impacts and conservation responses for the critically endangered European Atlantic sturgeon. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 2441–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costábile, A.; Castellano, M.; Aversa-Marnai, M.; Quartiani, I.; Conijeski, D.; Perretta, A.; Villarino, A.; Silva-Álvarez, V.; Ferreira, A.M. A different transcriptional landscape sheds light on Russian sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii) mechanisms to cope with bacterial infection and chronic heat stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 128, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhetawy, A.I.; Vasilyeva, L.M.; Lotfy, A.M.; Emelianova, N.; Abdel-Rahim, M.M.; Helal, A.M.; Sudakova, N.V. Effects of the rearing system of the Russian sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii) on growth, maturity, and the quality of produced caviar. Aquacult. Aquar. Conserv. Legis. 2020, 13, 3798–3809. [Google Scholar]

- Çelikkale, M.S.; Memiş, D.; Ercan, E.; Çağıltay, F. Growth performance of juvenile Russian sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii Brandt & Ratzenburg, 1833) at two stocking densities in net cages. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2005, 21, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havelka, M.; Kašpar, V.; Hulák, M.; Flajšhans, M. Sturgeon genetics and cytogenetics: A review related to ploidy levels and interspecific hybridization. Folia Zoologica. 2011, 60, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perretta, A.; Antúnez, K.; Zunino, P. Phenotypic, molecular and pathological characterization of motile aeromonads isolated from diseased fishes cultured in Uruguay. J. Fish Dis. 2018, 41, 1559–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, E.; Fast, M.D.; Purcell, S.L.; Denver Coleman, D.; Yazdi, Z.; Kenelty, K.; Yun, S.; Camus, A. Expression of immune markers of white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) during Veronaea botryosa infection at different temperatures. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D: Genom. Proteom. 2022, 41, 100950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouthier, S.; Caskenette, A.; Van Walleghem, E.; Schroeder, T.; Macdonald, D.; Anderson, E.D. Molecular phylogeny of sturgeon mimiviruses and Bayesian hierarchical modeling of their effect on wild Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) in Central Canada. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 84, 104491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beitinger, T.L.; Bennett, W.A.; McCauley, R.W. Temperature Tolerances of North American Freshwater Fishes Exposed to Dynamic Changes in Temperature. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2000, 58, 237–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegeweid, J.R.; Jennings, C.A.; Peterson, D.L. Thermal maxima for juvenile shortnose sturgeon acclimated to different temperatures. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2008, 82, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beitinger, T.L.; Lutterschmidt, W.I. Temperature|Measures of Thermal Tolerance. In Encyclopedia of Fish Physiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 3, pp. 1695–1702. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, M.; Wen, H.; Li, J.; Chi, M.; Bu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, M.; Song, Z.; Ding, H. The physiological performance and immune responses of juvenile Amur sturgeon (Acipenser schrenckii) to stocking density and hypoxia stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014, 36, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illing, B.; Downie, A.T.; Beghin, M.; Rummer, J.L. Critical thermal maxima of early life stages of three tropical fishes: Effects of rearing temperature and experimental heating rate. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 90, 102582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, A.; Latombe, G.; Chown, S.L. Rate dynamics of ectotherm responses to thermal stress. Proc. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2019, 286, 20190174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bruce, T.J.; Su, B.; Li, S.; Dunham, R.A.; Wang, X. Environment-Dependent Heterosis and Transgressive Gene Expression in Reciprocal Hybrids between the Channel Catfish Ictalurus punctatus and the Blue Catfish Ictalurus furcatus. Biology 2022, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, M.B.; Maynard, B.T.; Rigby, M.; Wynne, J.W.; Taylor, R.S. Reciprocal hybrids of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) x brown trout (S. trutta) confirm a heterotic response to experimentally induced amoebic gill disease (AGD). Aquaculture 2023, 572, 739535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscari, E.; Barmintseva, A.; Pujolar, J.M.; Doukakis, P.; Mugue, N.; Congiu, L. Species and hybrid identification of sturgeon caviar: A new molecular approach to detect illegal trade. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2014, 14, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, W.; Li, L.; Ma, X.; Chen, J. Genetic variation and relationships of seven sturgeon species and ten interspecific hybrids. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2013, 45, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronzi, P.; Chebanov, M.; Michaels, J.T.; Wei, Q.; Rosenthal, H.; Gessner, J. Sturgeon meat and caviar production: Global update 2017. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2019, 35, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Zou, Y.; Li, P.; Li, L. Sturgeon aquaculture in China: Progress, strategies and prospects assessed on the basis of nation-wide surveys (2007–2009). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2011, 27, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, G.; Zhu, H. Regulation of 14-3-3β/α gene expression in response to salinity, thermal, and bacterial stresses in Siberian sturgeon (Acipenser baeri). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 46, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Li, D.; Feng, L.; Zhang, C.; Xi, D.; Liu, H.; Yan, C.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Transcriptome analysis reveals the high temperature induced damage is a significant factor affecting the osmotic function of gill tissue in Siberian sturgeon (Acipenser baerii). BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Chen, Q.; Yan, C.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Z.; Huang, X.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, S. Effects of Chronic Heat Stress on Kidney Damage, Apoptosis, Inflammation, and Heat Shock Proteins of Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser baerii). Animals 2023, 13, 3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Loughery, J.R.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Kieffer, J.D. Physiological and molecular responses of juvenile shortnose sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum) to thermal stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2017, 203, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugg, W.S.; Yoon, G.R.; Schoen, A.N.; Laluk, A.; Brandt, C.; Anderson, W.G.; Jeffries, K.M. Effects of acclimation temperature on the thermal physiology in two geographically distinct populations of lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens). Conserv. Physiol. 2020, 8, coaa087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, E.E.; Woo, N.Y. Impact of heavy metals and organochlorines on hsp70 and hsc70 gene expression in black sea bream fibroblasts. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006, 79, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, L.; Drauch Schreier, A.; Lepla, K.; McAdam, S.; McLellan, J.; Parsley, M.J.; Paragamian, V.; Young, S. Status of White Sturgeon (A cipenser transmontanus Richardson, 1863) throughout the species range, threats to survival, and prognosis for the future. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2016, 32, 261–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, I.; Linares-Casenave, J.; Van Eenennaam, J.P.; Doroshov, S.I. The effect of temperature stress on development and heat-shock protein expression in larval green sturgeon (Acipenser mirostris). Environ. Biol. Fishes 2007, 79, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, M.; Kieffer, J. Critical thermal maxima and hematology for juvenile Atlantic (Acipenser oxyrinchus Mitchill 1815) and shortnose (Acipenser brevirostrum Lesueur, 1818) sturgeons. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2016, 32, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, F.; Bugg, W.S.; Kieffer, J.D.; Jeffries, K.M.; Pavey, S.A. Atlantic sturgeon and shortnose sturgeon exhibit highly divergent transcriptomic responses to acute heat stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D Genom. Proteom. 2023, 45, 101058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penman, R.J.; Bugg, W.; Rost-Komiya, B.; Earhart, M.L.; Brauner, C.J. Slow heating rates increase thermal tolerance and alter mRNA HSP expression in juvenile white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus). J. Therm. Biol. 2023, 115, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gao, L.; Liu, W.; Tian, Z.; Wang, X.; Hu, H. Regulation of antioxidant defense in response to heat stress in Siberian sturgeon (Acipenser baerii). Aquaculture 2023, 572, 739551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.A.; Dichiera, A.M.; Brauner, C.J. Resetting thermal limits: 10-year-old white sturgeon display pronounced but reversible thermal plasticity. J. Therm. Biol. 2024, 119, 103807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Gong, Q.; Huang, X.; Wu, J.; Huang, A.; Kong, F.; Han, X.; et al. The multilevel responses of Acipenser baerii and its hybrids (A. baerii ♀ × A. schrenckii ♂) to chronic heat stress. Aquaculture 2021, 541, 736773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, I.A.; Bennett, A.F. Animals and Temperature: Phenotypic and Evolutionary Adaptation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lesser, M.P. Oxidative stress in marine environments: Biochemistry and physiological ecology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2006, 68, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.; Jain, S.K. Oxidative stress and apoptosis. Pathophysiology 2000, 7, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonso, S.; Gesto, M.; Sadoul, B. Temperature increase and its effects on fish stress physiology in the context of global warming. J. Fish Biol. 2021, 98, 1496–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.P.; Liu, S.Y.; Xie, C.X.; Zhang, X.Z. Effects of water temperature on serum content of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense system in Chinese sturgeon, Acipenser sinensis. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2008, 32, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Song, Z.; Xiao, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, P.; You, F. Insight into the heat resistance of fish via blood: Effects of heat stress on metabolism, oxidative stress and antioxidant response of olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus and turbot Scophthalmus maximus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 58, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kregel, K.C. Heat shock proteins: Modifying factors in physiological stress responses and acquired thermotolerance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 92, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.-O. Oxygen- and capacity-limitation of thermal tolerance: A matrix for integrating climate-related stressor effects in marine ecosystems. J. Exp. Biol. 2010, 213, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Meng, Z.; Huang, B.; Guan, C. Physiological response of juvenile turbot (Scophthalmus maximus. L) during hyperthermal stress. Aquaculture 2020, 529, 735645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, S.D.; Dickson, K.L.; Zimmerman, E.G.; Sanders, B.M. Tissue-specific patterns of synthesis of heat-shock proteins and thermal tolerance of the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). Can. J. Zool. 1991, 69, 2021–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares-Casenave, J.; Werner, I.; Van Eenennaam, J.; Doroshov, S. Temperature stress induces notochord abnormalities and heat shock proteins expression in larval green sturgeon (Acipenser medirostris Ayres 1854). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2013, 29, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Zhao, Z.G.; Zhang, R.; Guo, K.; Wang, S.H.; Xu, W.; Wang, C. The effects of temperature changes on the isozyme and Hsp70 levels of the Amur sturgeon, Acipenser schrenckii, at two acclimation temperatures. Aquaculture 2022, 551, 737743–737753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Lai, J.; Liu, Y.; Song, M.; Li, F.; Gong, Q. Integrated biochemical, transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses provide insight into heat stress response in Yangtze sturgeon (Acipenser dabryanus). Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2023, 249, 114366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narum, S.R.; Campbell, N.R.; Meyer, K.A.; Miller, M.R.; Hardy, R.W. Thermal adaptation and acclimation of ectotherms from differing aquatic climates. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 3090–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Deng, D.F.; De Riu, N.; Moniello, G.; Hung, S. Heat Shock Protein 70 (HSP70) Responses in Tissues of White Sturgeon and Green Sturgeon Exposed to Different Stressors. N. Am. J. Aquacult. 2013, 75, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Zhao, W.; Shi, Z.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Wei, J.; Gao, F. Cloning HSP70 and HSP90 genes of kaluga (Huso dauricus) and the effects of temperature and salinity stress on their gene expression. Cell Stress Chaperones 2016, 21, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santacruz, H.; Vriz, S.; Angelier, N. Molecular characterization of a heat shock cognate cDNA of zebrafish, hsc70, and developmental expression of the corresponding transcripts. Dev. Genet. 1997, 21, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.T.; Wang, N.; Liao, X.L.; Meng, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.L. Cloning, molecular characterization and expression analysis of heat shock cognate 70 (Hsc70) cDNA from turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 39, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, G.C.; Chen, Y.N.; Guo, J.Q.; Pan, C.L.; Liu, E.G.; Ling, Q.F. Physicochemical changes in liver and Hsc70 expression in pikeperch Sander lucioperca under heat stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 181, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabergh, C.M.; Airaksinen, S.; Soitamo, A.; Bjorklund, H.V.; Johansson, T.; Nikinmaa, M.; Sistonen, L. Tissue-specific expression of zebrafish (Danio rerio) heat shock factor 1 mRNAs in response to heat stress. J. Exp. Biol. 2000, 203, 1817–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.Y.; Chen, Y.M.; Chen, T.Y. Molecular cloning of orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides) heat shock transcription factor 1 isoforms and characterization of their expressions in response to nodavirus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 59, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allais, L.; Zhao, C.; Fu, M.; Hu, J.; Qin, J.G.; Qiu, L.; Ma, Z. Nutrition and water temperature regulate the expression of heat-shock proteins in golden pompano larvae (Trachinotus ovata, Limmaeus 1758). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 45, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.S.; He, J.-R.; Hester, L.; Fenton, M.J.; Hasday, J.D. Bacterial endotoxin modifies heat shock factor-1 activity in RAW 264.7 cells: Implications for TNF-α regulation during exposure to febrile range temperatures. J. Endotoxin Res. 2004, 10, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldi, E.; Di Marco, P.; Mandich, A.; Cataudella, S. Serum parameters of Adriatic sturgeon Acipenser naccarii (Pisces: Acipenseriformes): Effects of temperature and stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 1998, 121, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, M.; Silva-Álvarez, V.; Fernández-López, E.; Mauris, V.; Conijeski, D.; Villarino, A.; Ferreira, A.M. Russian sturgeon cultured in a subtropical climate shows weaken innate defences and a chronic stress response. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 68, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.Y. Aquatic Animal Immune and Application; Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2007; Volume 145, pp. 182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, M.A.; Allert, J.A.; Kappenman, K.M.; Marcos, J.; Feist, G.W.; Schreck, C.B.; Shackleton, C.H. Identification of plasma glucocorticoids in pallid sturgeon in response to stress. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2007, 154, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kieffer, J.D. Critical thermal maximum (CTmax) and hematology of shortnose sturgeons (Acipenser brevirostrum) acclimated to three temperatures. Can. J. Zool. 2014, 92, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, B.; Kieffer, J.D. The effects of repeat acute thermal stress on the critical thermal maximum (CTmax) and physiology of juvenile shortnose sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum). Can. J. Zool. 2019, 97, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechlaoui, M.; Dominguez, D.; Robaina, L.; Geraert, P.-A.; Kaushik, S.; Saleh, R.; Briens, M.; Montero, D.; Izquierdo, M. Effects of different dietary selenium sources on growth performance, liver and muscle composition, antioxidant status, stress response and expression of related genes in gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata). Aquaculture 2019, 507, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M.A.; Zommara, M.; Eweedah, N.M.; Helal, A.I. Synergistic effects of selenium nanoparticles and vitamin E on growth, immune-related gene expression, and regulation of antioxidant status of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 195, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jawasreh, R.I.M. Analytical and Biological Studies on the Immunomodulatory Potential of Flavonoids in Fish Aquaculture; Università Ca’Foscari Venezia: Venezia, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mahanty, A.; Mohanty, S.; Mohanty, B.P. Dietary supplementation of curcumin augments heat stress tolerance through upregulation of nrf-2-mediated antioxidative enzymes and hsps in Puntius sophore. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Latif, H.M.; Shukry, M.; Noreldin, A.E.; Ahmed, H.A.; El-Bahrawy, A.; Ghetas, H.A.; Khalifa, E. Milk thistle (Silybum marianum) extract improves growth, immunity, serum biochemical indices, antioxidant state, hepatic histoarchitecture, and intestinal histomorphometry of striped catfish, Pangasianodon hypophthalmus. Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L. The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F.; Xiao, P.; Chen, D.; Xu, L.; Zhang, B. miRDeepFinder: A miRNA analysis tool for deep sequencing of plant small RNAs. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012, 80, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Gene Symbol | Primers (5′-3′) | Length (bp) | R2 | Efficiency % | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b-actin | bact | F: TGCCATCCAGGCTGTGCT | 215 | 0.997 | 93.827 | JX027376.1 |

| R: TCTCGGCTGTGGTGGTGAAG | ||||||

| elongation factor 1 alpha | ef1a | F: GGACTCCACTGAGCCACCT | 89 | 0.989 | 108.07 | JQ995144.1 |

| R: GGGTTGTAGCCGATCTTCTTG | ||||||

| heat shock transcription factors 1 | hsf1 | F: ATTAGCCACGGTCACACACA | 158 | 0.989 | 96.913 | XM_033993892.2 |

| R: GAAACAGCAGTCACCTTCCC | ||||||

| heat shock cognate 70 | hsc70 | F: CCTCTAAGAGAGCGGCTGAG | 100 | 0.993 | 93.716 | XM_033995557.2 |

| R: TTACTGCAGCTCGGAAGAGAG | ||||||

| heat shock protein 70 | hsp70 | F: CCCTACCATCGAGGAGGTTG | 168 | 0.995 | 91.279 | HM348777.1 |

| R: AATGACCAGCGTTGGCTTAC | ||||||

| heat shock protein 90 | hsp90 | F: TGAGGATGTTGGCTCTGATG | 110 | 0.999 | 96.250 | JX477807.1 |

| R: AGATGGGCTTGGTCTTGTTC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, W.; Gao, L.; Yan, X.; Liu, W.; Dong, T.; Song, H.; Ma, G.; Hu, H. Comparative Thermal Tolerance and Tissue-Specific Responses Patterns to Gradual Heat Stress in Reciprocal Cross Hybrids of Acipenser baerii and A. schrenckii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010132

Wang W, Gao L, Yan X, Liu W, Dong T, Song H, Ma G, Hu H. Comparative Thermal Tolerance and Tissue-Specific Responses Patterns to Gradual Heat Stress in Reciprocal Cross Hybrids of Acipenser baerii and A. schrenckii. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010132

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Wei, Linan Gao, Xiaoyu Yan, Wenjie Liu, Tian Dong, Hailiang Song, Guoqing Ma, and Hongxia Hu. 2026. "Comparative Thermal Tolerance and Tissue-Specific Responses Patterns to Gradual Heat Stress in Reciprocal Cross Hybrids of Acipenser baerii and A. schrenckii" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010132

APA StyleWang, W., Gao, L., Yan, X., Liu, W., Dong, T., Song, H., Ma, G., & Hu, H. (2026). Comparative Thermal Tolerance and Tissue-Specific Responses Patterns to Gradual Heat Stress in Reciprocal Cross Hybrids of Acipenser baerii and A. schrenckii. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010132