Pilot Proteomic Analysis of Urinary Extracellular Vesicles Supports the “Toxic Urine Hypothesis” as a Vicious Cycle in Refractory IC/BPS Pathogenesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

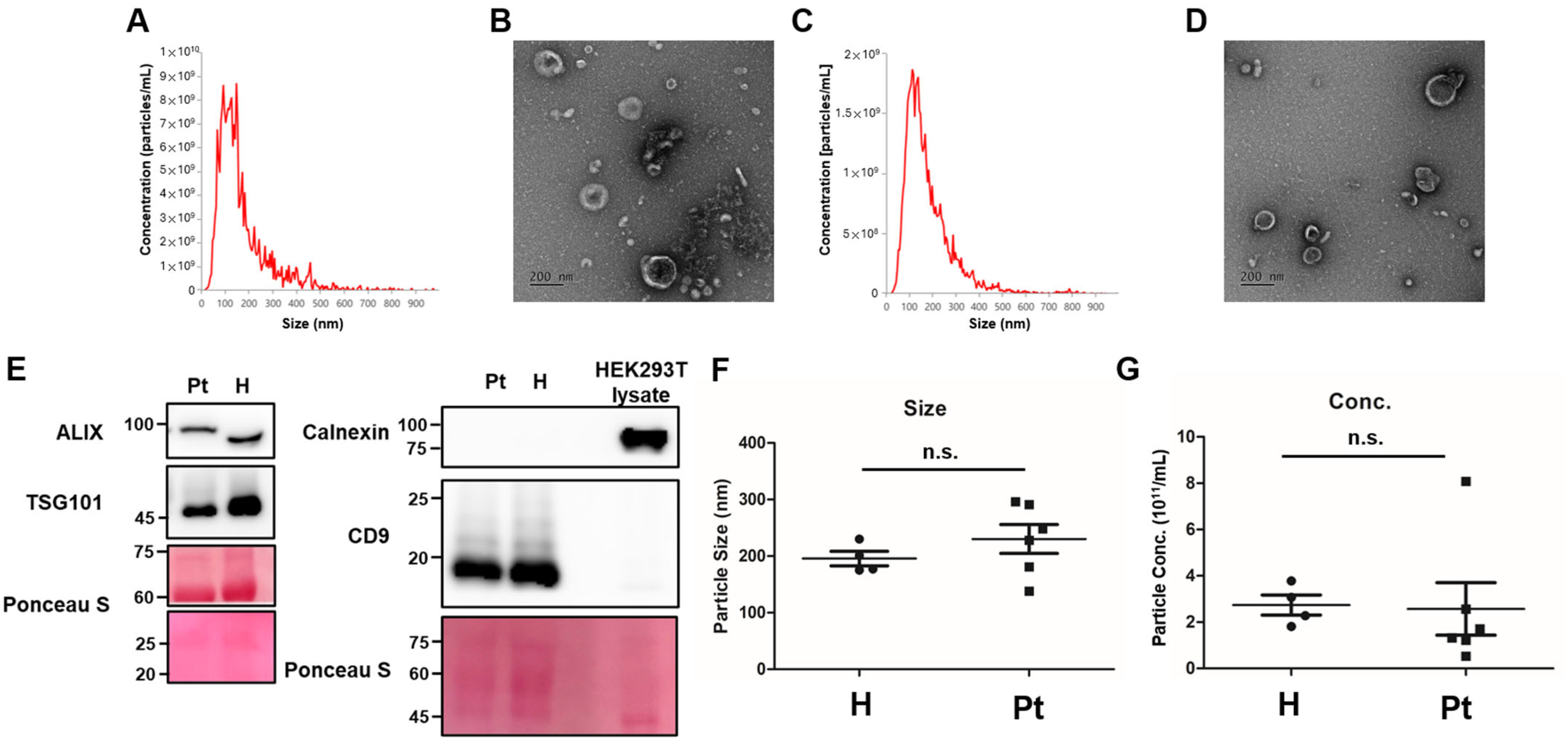

2.2. Characterization of Urinary Extracellular Vesicles (uEVs)

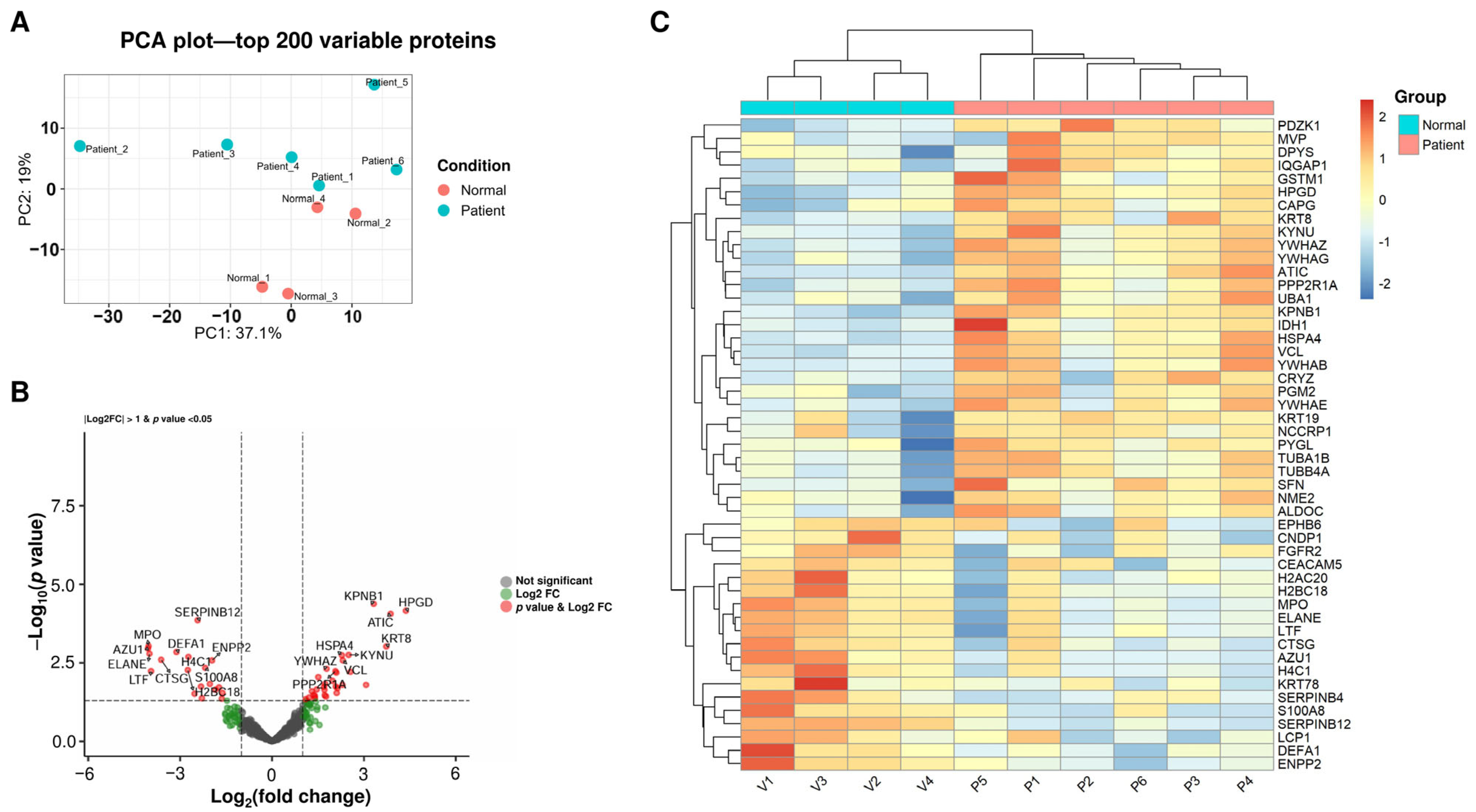

2.3. Proteomic Analysis of uEVs Reveals the Suppression of Neutrophil-Mediated Inflammation in Treated IC Patients

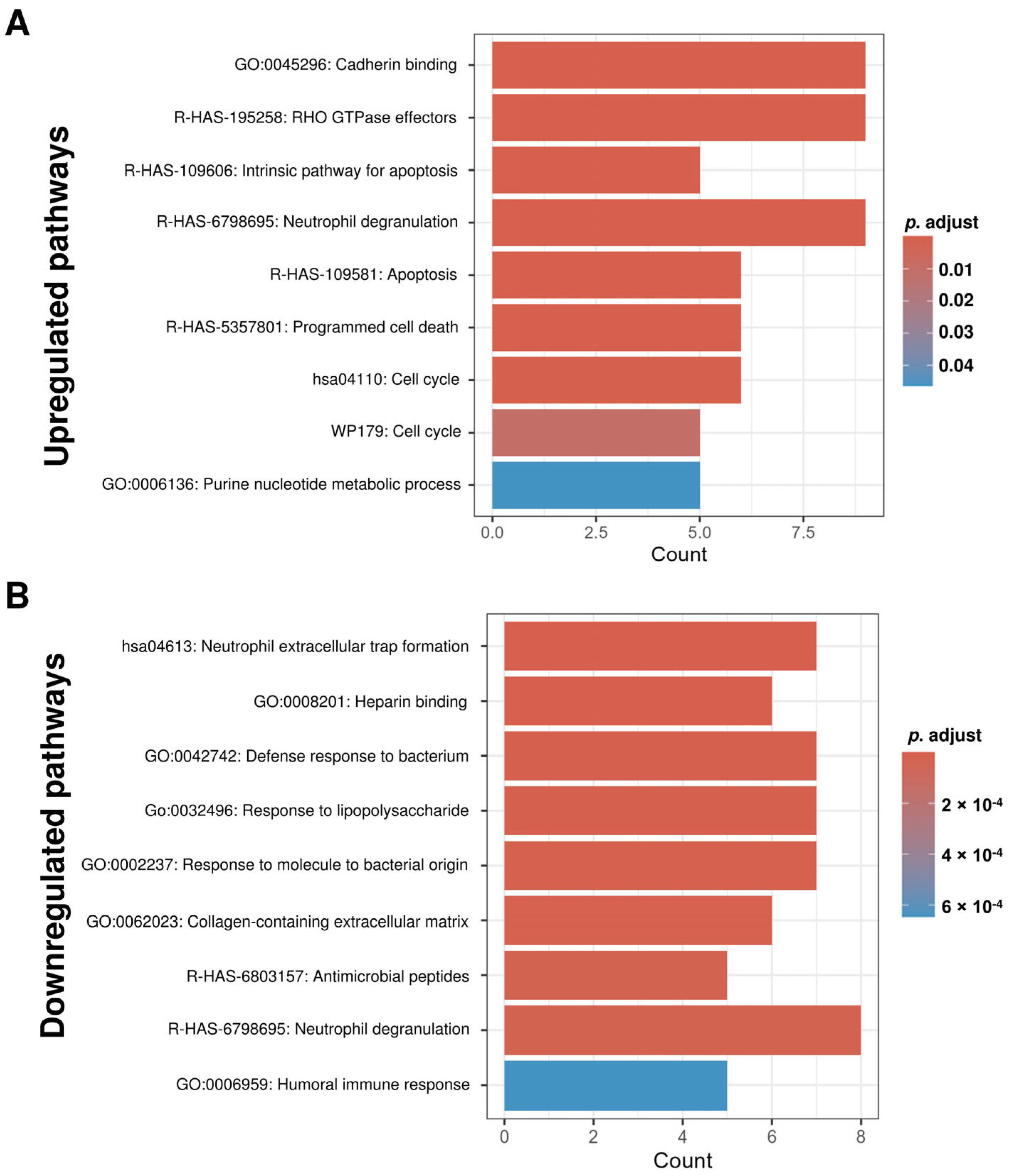

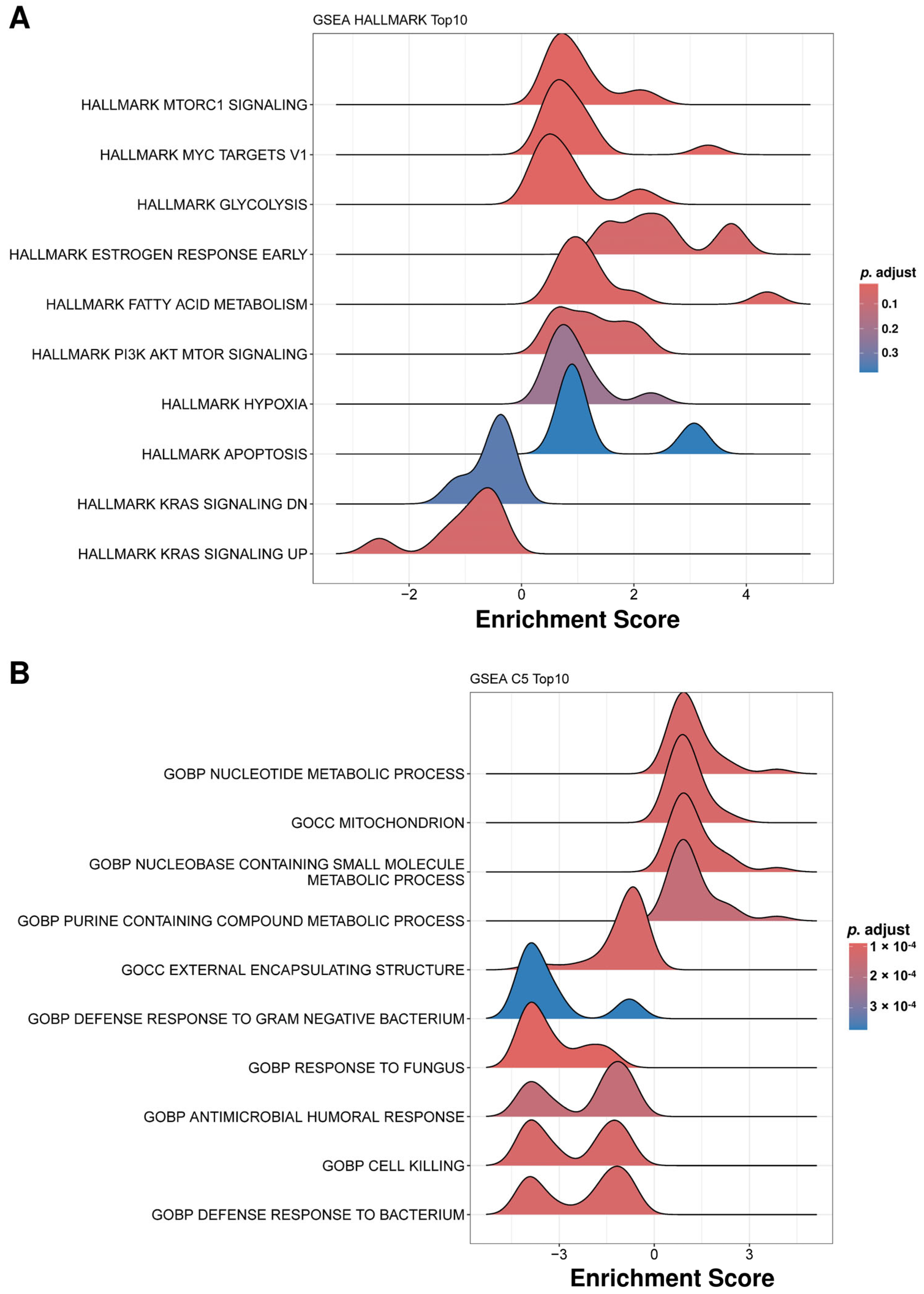

2.4. Functional Enrichment Analysis Reveals Distinct Biological Pathways Associated with Protein Alterations in IC Patient uEVs

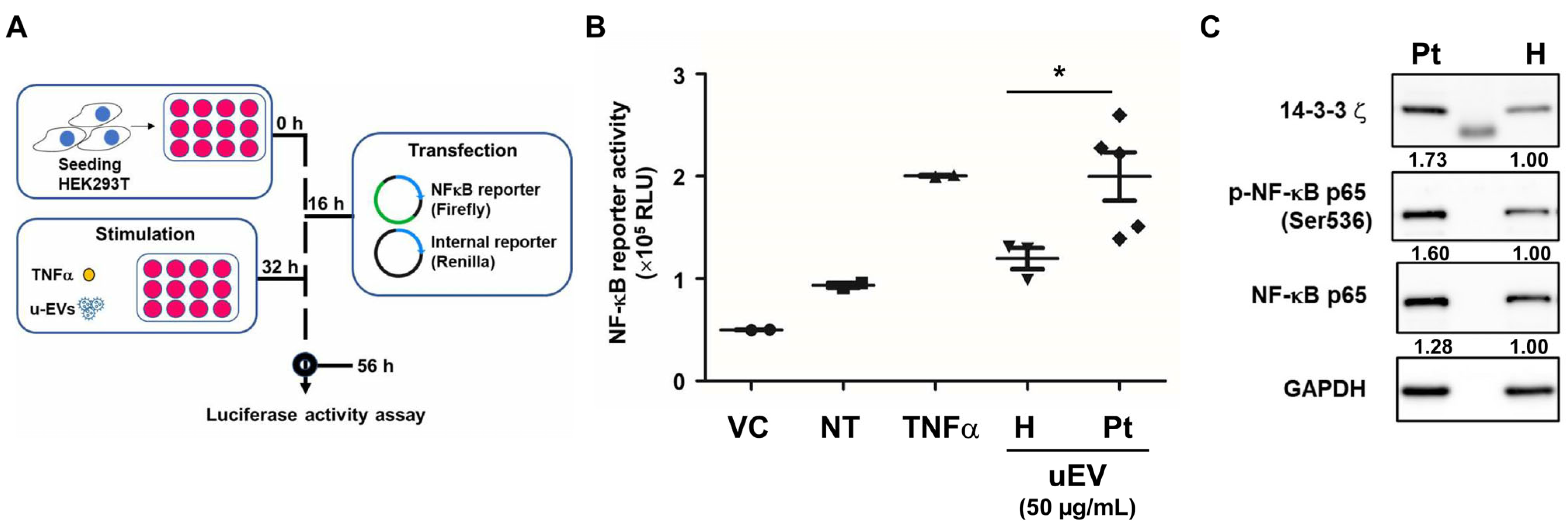

2.5. Urinary EVs from IC Patients Enhance NF-κB Activation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Patient Enrollment

4.2. Urinary EV (uEV) Isolation

4.3. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

4.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

4.5. Proteomic Analysis

4.6. Western Blot Analysis

4.7. Cell Culture

4.8. Luciferase Reporter Assay

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van de Merwe, J.P.; Nordling, J.; Bouchelouche, P.; Bouchelouche, K.; Cervigni, M.; Daha, L.K.; Elneil, S.; Fall, M.; Hohlbrugger, G.; Irwin, P.; et al. Diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature for painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: An ESSIC proposal. Eur. Urol. 2008, 53, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcu, I.; Campian, E.C.; Tu, F.F. Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2018, 36, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLennan, M.T. Interstitial cystitis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical presentation. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 41, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.R.; Jhang, J.F.; Jiang, Y.H.; Kuo, H.C. The Pathomechanism and Current Treatments for Chronic Interstitial Cystitis and Bladder Pain Syndrome. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, K.; Kim, Y.K.; Rhee, T.G.; Shim, S.R.; Kim, J.H. Pentosan Polysulfate Sodium and Maculopathy in Patients with Interstitial Cystitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J. Men’s Health 2025, 43, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.L.; Lee, F.K.; Wang, P.H. Application of hyaluronic acid in patients with interstitial cystitis. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2021, 84, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, A.; Hennessy, D.B.; Curry, D.; Cartwright, C.; Downey, P.; Pahuja, A. Intravesical chondroitin sulphate for interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Ulst. Med. J. 2015, 84, 161–163. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.R.; Shen, S.H.; Gao, X.S.; Peng, L.; Luo, D.Y. The Efficacy and Safety of Dimethyl Sulfoxide Into the Bladder for the Treatment of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2025, 44, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.C. Clinical Application of Botulinum Neurotoxin in Lower-Urinary-Tract Diseases and Dysfunctions: Where Are We Now and What More Can We Do? Toxins 2022, 14, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.; Adel, M.; Elnagar, M.A.; Elsonbaty, S.; Hefnawy, A.E. How Intravesical Platelet-Rich Plasma Can Help Patients with Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome: A Comprehensive Scoping Review. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2024, 35, 1735–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.R.; Wang, T.; Shen, S.H.; Peng, L. The efficacy and safety of intravesical platelet-rich plasma injections into the bladder for the treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Minerva Urol. Nephrol. 2025, 77, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, B.; Shorter, B.; Sarcona, A.; Moldwin, R.M. Nutritional considerations for patients with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.B.; Wu, M.P.; Lin, Y.K.; Yen, Y.C.; Chuang, Y.C.; Chin, H.Y. Lifestyle and behavioral modifications made by patients with interstitial cystitis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh-Oka, H. Clinical Efficacy of 1-Year Intensive Systematic Dietary Manipulation as Complementary and Alternative Medicine Therapies on Female Patients with Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. Urology 2017, 106, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.R.; Jiang, Y.H.; Jhang, J.F.; Kuo, H.C. Urine biomarker could be a useful tool for differential diagnosis of a lower urinary tract dysfunction. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2024, 36, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Lu, J.H.; Chuang, S.M.; Chueh, K.S.; Juan, T.J.; Liu, Y.C.; Juan, Y.S. Urinary Biomarkers in Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome and Its Impact on Therapeutic Outcome. Diagnostics 2021, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Oliveira, R.; Antunes-Lopes, T.; Cruz, C.D. Partners in Crime: NGF and BDNF in Visceral Dysfunction. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 1021–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.R.; Jiang, Y.H.; Jhang, J.F.; Kuo, H.C. Use of Urinary Biomarkers in Discriminating Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome from Male Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunctions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrugger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404, Erratum in J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12451. https://doi.org/10.1002/jev2.12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessler, S.; Meisner-Kober, N. On the road: Extracellular vesicles in intercellular communication. Cell Commun. Signal. 2025, 23, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Xie, L.; Hu, C. Roles of mesenchymal stem cells and exosomes in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2022, 26, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Chen, Y.; Liu, R.; Chen, B.; Liu, C.; Xing, J. Long noncoding RNA (MEG3) in urinal exosomes functions as a biomarker for the diagnosis of Hunner-type interstitial cystitis (HIC). J. Cell. Biochem. 2020, 121, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Bi, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Wu, X.; Jing, X.; Wang, H. MiR-9-enriched mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes prevent cystitis-induced bladder pain via suppressing TLR4/NLRP3 pathway in interstitial cystitis mice. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2024, 12, e1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.S.; Park, J.H.; Yoo, S.A.; Kim, K.M.; Bae, Y.J.; Park, Y.J.; Cho, C.S.; Hwang, D.; Kim, W.U. Dynamic transcriptome analysis unveils key proresolving factors of chronic inflammatory arthritis. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 3974–3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Huang, H.; Guo, Z.; Chang, Y.; Li, Z. Role of prostaglandin E2 in tissue repair and regeneration. Theranostics 2021, 11, 8836–8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marentette, J.O.; Hurst, R.E.; McHowat, J. Impaired Expression of Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) Synthesis and Degradation Enzymes during Differentiation of Immortalized Urothelial Cells from Patients with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, T.; Sakurai, T.; Kashida, H.; Mine, H.; Hagiwara, S.; Matsui, S.; Yoshida, K.; Nishida, N.; Watanabe, T.; Itoh, K.; et al. Involvement of heat shock protein a4/apg-2 in refractory inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffers, P.; Guckenbiehl, S.; Welker, M.W.; Zeuzem, S.; Lange, C.M.; Trebicka, J.; Herrmann, E.; Welsch, C. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of cell death markers in patients with cirrhosis and acute decompensation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehaus, J.Z.; Good, M.; Jackson, L.E.; Ozolek, J.A.; Silverman, G.A.; Luke, C.J. Human SERPINB12 Is an Abundant Intracellular Serpin Expressed in Most Surface and Glandular Epithelia. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2015, 63, 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, S.; Laudadio, I.; Fulci, V.; Rossetti, D.; Isoldi, S.; Stronati, L.; Carissimi, C. SERPINB12 as a possible marker of steroid dependency in children with eosinophilic esophagitis: A pilot study. Dig. Liver Dis. 2020, 52, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, M.A.; Yavuz, H.; Gathmann, A.; Upson, S.; Swiatecka-Urban, A.; Erdbrugger, U. Uromodulin and the study of urinary extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Biol. 2024, 3, e70022, Correction in J. Extracell. Biol. 2025, 4, e70070. https://doi.org/10.1002/jex2.70070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, V.L.; Otto, J.J.; Risi, C.M.; Main, B.P.; Boutros, P.C.; Kislinger, T.; Galkin, V.E.; Nyalwidhe, J.O.; Semmes, O.J.; Yang, L. Optimization of small extracellular vesicle isolation from expressed prostatic secretions in urine for in-depth proteomic analysis. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IC Patients | Age (years) | BMI (kg/m2) | Duration (months) | ESSIC Typing 1 | Glomerulation Initial/Current 1 | Cystoscopic Capacity (mL) | Urinary Frequency | VV 2 (mL) | FBC 2 (mL) | ICSI 3 (0–20) | ICPI 3 (0–16) | Pain-VAS 3 | Additional Tx 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 61 | 21.9 | 26 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 650 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | 175.4 ± 10.1 | 280 | 10 | 12 | 6 | PRP |

| 2 | 36 | 18.4 | 97 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 700 | 16.7 ± 0.6 | 51.6 ± 3.6 | 110 | 20 | 16 | 10 | BOTOX, PRP |

| 3 | 49 | 21.6 | 86 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 600 | 11.0 ± 1.0 | 134.0 ± 10.6 | 300 | 10 | 9 | 2 | BOTOX, PRP |

| 4 | 34 | 19.4 | 76 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 550 | 9.3 ± 0.6 | 123.4 ± 9.6 | 210 | 4 | 4 | 2 | PRP |

| 5 | 47 | 20.9 | 28 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 800 | 14.7 ± 2.3 | 57.0 ± 4.9 | 220 | 16 | 15 | 10 | PRP |

| 6 | 49 | 21.6 | 113 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 850 | 11.3 ± 2.1 | 106.7 ± 12.5 | 260 | 5 | 4 | 4 | BOTOX, PRP |

| Mean ± SD | 46.0 ± 9.9 | 20.6 ± 1.4 | 71.0 ± 36.2 | 691.7 ± 115.8 | 11.8 ± 3.3 | 108.0 ± 45.2 | 230.0 ± 68.1 | 10.8 ± 6.2 | 10.0 ± 5.3 | 5.7 ± 3.7 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hung, M.-J.; Yang, E.; Ying, T.-H.; Chien, P.-J.; Huang, Y.-T.; Chang, W.-W. Pilot Proteomic Analysis of Urinary Extracellular Vesicles Supports the “Toxic Urine Hypothesis” as a Vicious Cycle in Refractory IC/BPS Pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010130

Hung M-J, Yang E, Ying T-H, Chien P-J, Huang Y-T, Chang W-W. Pilot Proteomic Analysis of Urinary Extracellular Vesicles Supports the “Toxic Urine Hypothesis” as a Vicious Cycle in Refractory IC/BPS Pathogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010130

Chicago/Turabian StyleHung, Man-Jung, Evelyn Yang, Tsung-Ho Ying, Peng-Ju Chien, Ying-Ting Huang, and Wen-Wei Chang. 2026. "Pilot Proteomic Analysis of Urinary Extracellular Vesicles Supports the “Toxic Urine Hypothesis” as a Vicious Cycle in Refractory IC/BPS Pathogenesis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010130

APA StyleHung, M.-J., Yang, E., Ying, T.-H., Chien, P.-J., Huang, Y.-T., & Chang, W.-W. (2026). Pilot Proteomic Analysis of Urinary Extracellular Vesicles Supports the “Toxic Urine Hypothesis” as a Vicious Cycle in Refractory IC/BPS Pathogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010130