KRASAVA—An Expert System for Virtual Screening of KRAS G12D Inhibitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

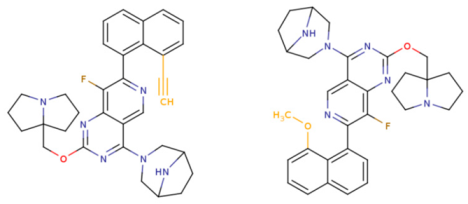

- 1.

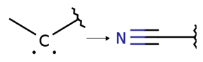

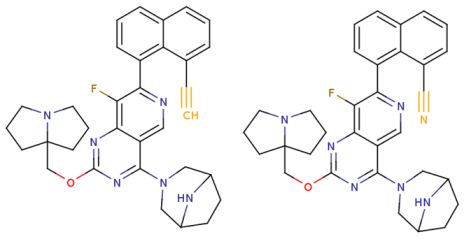

- Substitution of a nitrile group with a hydroxy or alkyne group (molecular transformations 1 and 5 in Table 2), which is consistent with the high contribution to activity of descriptors No. 4 and 9 shown in Figure 2A and Table A2, as well as descriptors No. 4, 6, and 9 shown in Figure 2B and Table A3;

- 2.

- Replacement of a methoxy group with an alkyne group (molecular transformation 2 in Table 2);

- 3.

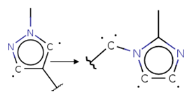

- Replacement of a pyridine fragment with a 1-methylpyrrolidine fragment (molecular transformation 3 in Table 2);

- 4.

- Substitution of a methoxy group with a hydroxy group (molecular transformation 4 in Table 2);

- 5.

- Replacement of an ethylene fragment with a pyrrolizidine fragment (molecular transformation 6 in Table 2);

- 6.

- 7.

- Elongation of the linker connected to the imidazole ring (molecular transformation 8 in Table 2);

- 8.

- 9.

- Replacement of a pyridine fragment with an imidazole ring (molecular transformation 10 in Table 2).

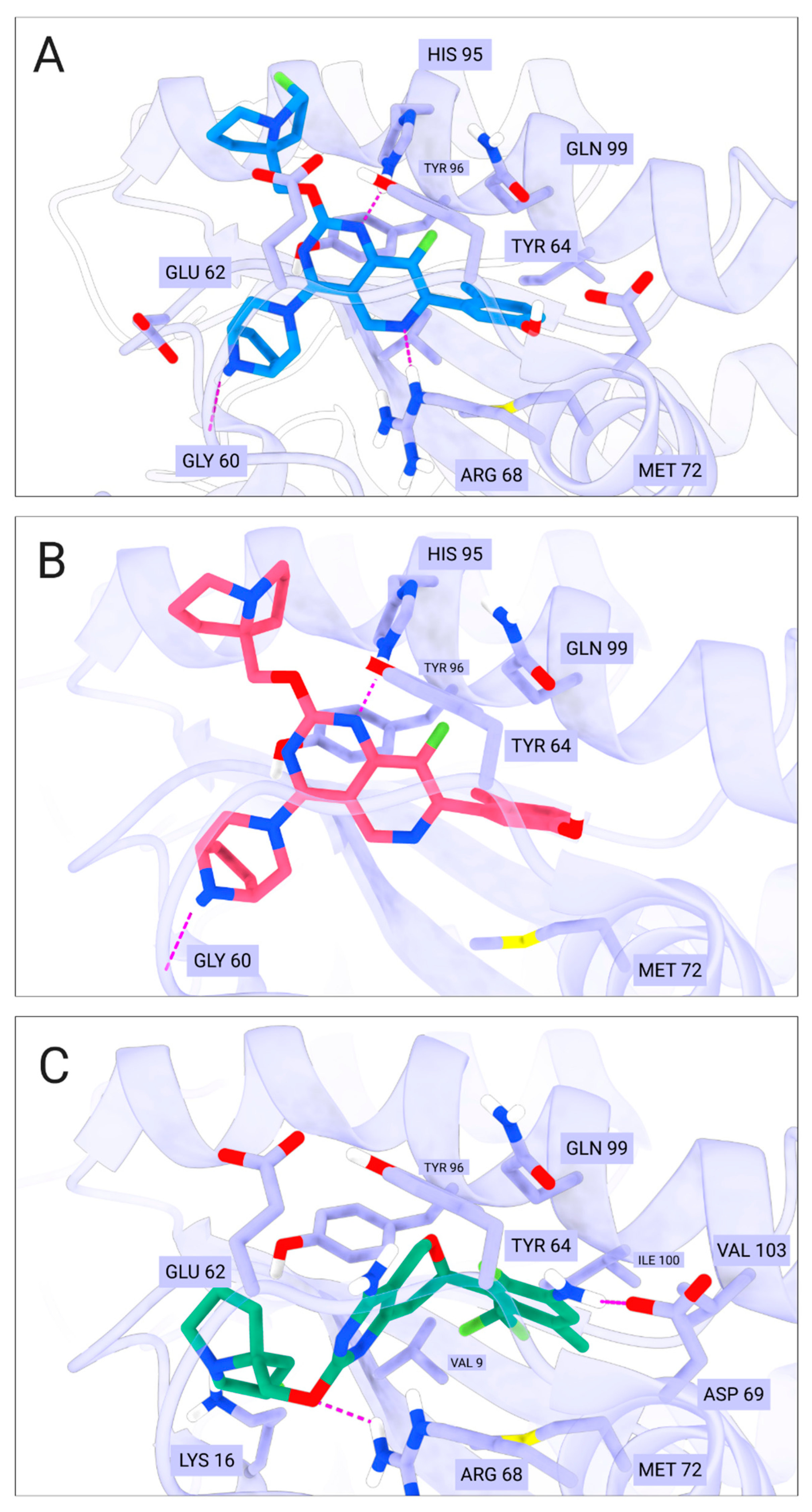

- Ionic interactions with Asp12—compound MRTX1133;

- Gly60 hydrogen bond—compound MRTX1133, compound 1 and compound 2;

- His95 hydrogen bond—compounds MRTX1133, BDBM573509, compound 1 and compound 2;

- Arg68 hydrogen bond—compounds MRTX1133, BDBM573509, compound 1 and compound 3;

- Asp69 hydrogen bond—compound MRTX1133 and compound 3.

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Dataset of KRAS G12D Inhibitors

3.2. Development of QSAR Models

3.3. Framework KRASAVA

3.4. Molecular Docking

4. Conclusions

- Development of a series of regression QSAR models for KRAS G12D inhibitors using ECFP4, Klekota-Roth, PubChem, MACCS, Topological Torsion, Atom Pairs, Topological Path-Based fingerprints, and RDKit descriptors, along with CatBoost, SVM, and MLP algorithms, as well as models developed via the OCHEM platform;

- Structural interpretation of QSAR models for KRAS G12D inhibitors, identifying the most significant fragments and molecular transformations;

- Integration of the consensus QSAR model into the KRASAVA framework, enabling retrieval of experimental data for investigated compounds, as well as virtual screening of potential KRAS G12D inhibitors with preliminary assessment of bioavailability through Muegge’s rules compliance, and evaluation of acute toxicity via identification of key toxicophores and Brenk filters;

- Rational molecular design of compounds based on the structural interpretation results and capabilities of the KRASAVA framework, leading to the proposal of two most promising KRAS G12D inhibitors;

- Comparative analysis of the proposed compounds through molecular docking, examining the nature of their interactions with the KRAS G12D binding site, and validating the results obtained from QSAR structural interpretation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QSAR | Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationships |

| AD | Applicability Domain |

| 5-fold CV | Five-fold Internal Cross-validation |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Descriptors | Algorithms | Training Set, 5-Fold CV | Test Set, All Compounds | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | RMSE | ||||

| ALogPS, OEstate | RFR | 0.57 | 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.79 |

| ASNN | 0.59 | 0.78 | 0.50 | 0.87 | |

| KNN | 0.51 | 0.85 | 0.46 | 0.91 | |

| MLRA | 0 | 1.4 | 0.44 | 0.93 | |

| DNN | 0.58 | 0.79 | 0.50 | 0.91 | |

| XGBOOST | 0.57 | 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.79 | |

| CDK | RFR | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.81 |

| ASNN | 0.59 | 0.78 | 0.53 | 0.85 | |

| KNN | 0.50 | 0.86 | 0.49 | 0.88 | |

| MLRA | 0.47 | 0.89 | 0 | 1.3 | |

| DNN | 0.58 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 0.89 | |

| XGBOOST | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.79 | |

| Dragon | RFR | 0.58 | 0.79 | 0.58 | 0.80 |

| ASNN | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.73 | |

| KNN | 0.51 | 0.85 | 0.53 | 0.85 | |

| MLRA | 0 | 1.5 | 0.36 | 0.99 | |

| DNN | 0.54 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 0.80 | |

| XGBOOST | 0.57 | 0.80 | 0.54 | 0.84 | |

| Fragmentor (length: 2–4) | RFR | 0.60 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.77 |

| ASNN | 0.55 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 0.77 | |

| KNN | 0.49 | 0.87 | 0.50 | 0.88 | |

| MLRA | 0.54 | 0.83 | 0.54 | 0.83 | |

| DNN | 0.45 | 0.91 | 0.5 | 0.85 | |

| XGBOOST | 0.57 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 0.79 | |

| MOLD2 | RFR | 0.59 | 0.78 | 0.58 | 0.80 |

| ASNN | 0.59 | 0.78 | 0.50 | 0.84 | |

| KNN | 0.48 | 0.88 | 0.49 | 0.88 | |

| MLRA | 0.49 | 0.87 | 0 | 7 | |

| DNN | 0.45 | 0.91 | 0.52 | 0.86 | |

| XGBOOST | 0.58 | 0.79 | 0.59 | 0.79 | |

| MORDRED | RFR | 0.59 | 0.78 | 0.58 | 0.8 |

| ASNN | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.71 | |

| KNN | 0.52 | 0.85 | 0.49 | 0.89 | |

| MLRA | 0 | 2.8 | 0 | 8 | |

| DNN | 0.51 | 0.85 | 0.5 | 0.88 | |

| XGBOOST | 0.57 | 0.80 | 0.57 | 0.81 | |

| QNPR | RFR | 0.59 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.77 |

| ASNN | 0.45 | 0.90 | 0.52 | 0.86 | |

| KNN | 0.38 | 0.96 | 0.36 | 0.99 | |

| MLRA | 0.42 | 0.93 | 0.52 | 0.86 | |

| DNN | 0.43 | 0.92 | 0.61 | 0.77 | |

| XGBOOST | 0.55 | 0.82 | 0.57 | 0.81 | |

| ECFP4 | RFR | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.69 |

| ASNN | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.72 | |

| KNN | 0.56 | 0.81 | 0.60 | 0.79 | |

| MLRA | 0.23 | 1.07 | 0.4 | 1 | |

| DNN | 0.51 | 0.86 | 0.4 | 0.94 | |

| XGBOOST | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.71 | |

| RDKIT | RFR | 0.55 | 0.82 | 0.56 | 0.82 |

| ASNN | 0.68 | 0.7 | 0.67 | 0.71 | |

| KNN | 0.53 | 0.84 | 0.51 | 0.87 | |

| MLRA | 0 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 1 | |

| DNN | 0.51 | 0.86 | 0.4 | 0.94 | |

| XGBOOST | 0.54 | 0.83 | 0.56 | 0.82 | |

| alvaDesc | RFR | 0.59 | 0.78 | 0.59 | 0.79 |

| ASNN | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.73 | |

| KNN | 0.51 | 0.86 | 0.51 | 0.87 | |

| MLRA | 0 | 1.6 | 0 | 9 | |

| DNN | 0.53 | 0.83 | 0.56 | 0.82 | |

| XGBOOST | 0.59 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 0.76 | |

| - | AttFP AttFP | 0.54 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 0.73 |

| - | ChemProp | 0.53 | 0.84 | 0.61 | 0.77 |

| - | TRANSNNI | 0.60 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.72 |

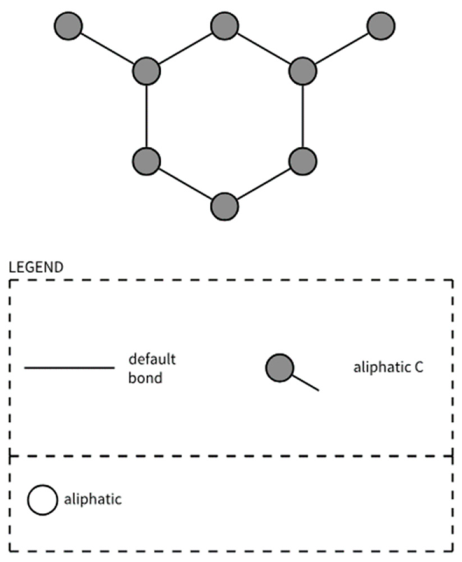

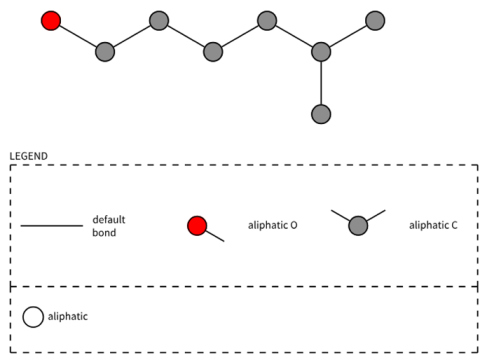

| ID and SMARTS or Identifier of Substructure | Descriptor Visualization |

|---|---|

| KRFP1932 [!#1]c1[cH]c([!#1])c([!#1])c([!#1])[cH]1 |  |

| KRFP4740 Oc1ccc2ccccc2c1 |  |

| KRFP3139 c1ccc2ccccc2c1 |  |

| KRFP2949 [OH] |  |

| KRFP3592 Cc1cccc2ccccc12 |  |

| KRFP1566 [!#1]c1[cH][cH][cH][cH]c1[!#1] |  |

| KRFP3751 CCN(C)C |  |

| KRFP3719 CCCCCCC |  |

| KRFP1148 [!#1][OH] |  |

| ID | SMARTS or Identifier of Substructure | Descriptor Visualization |

|---|---|---|

| PubchemFP336 | C(~C)(~C)(~C)(~N) |  |

| PubchemFP157 | >=3 any ring size 5 | |

| PubchemFP160 | >=3 saturated or aromatic heteroatom-containing ring size 5 | |

| PubchemFP590 | C-C:C-O-[#1] |  |

| PubchemFP714 | Cc1ccc(O)cc1 |  |

| PubchemFP659 | O-C-C-N-C |  |

| PubchemFP152 | >=2 saturated or aromatic nitrogen-containing ring size 5 | |

| PubchemFP797 | CC1CC(C)CCC1 |  |

| PubchemFP699 | O-C-C-C-C-C(C)-C |  |

References

- Bannoura, S.F.; Khan, H.Y.; Azmi, A.S. KRAS G12D Targeted Therapies for Pancreatic Cancer: Has the Fortress Been Conquered? Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1013902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Pei, L.; Xia, H.; Tang, Q.; Bi, F. Role of Oncogenic KRAS in the Prognosis, Diagnosis and Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeissig, M.N.; Ashwood, L.M.; Kondrashova, O.; Sutherland, K.D. Next Batter up! Targeting Cancers with KRAS-G12D Mutations. Trends Cancer 2023, 9, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.D.; Der, C.J. Ras History. Small GTPases 2010, 1, 2–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, I.A.; Lewis, P.D.; Mattos, C. A Comprehensive Survey of Ras Mutations in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 2457–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.B.; Corcoran, R.B. Therapeutic Strategies to Target RAS-Mutant Cancers. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Inhibition of GTPase KRASG12D: A Review of Patent Literature. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2024, 34, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Maldonado, C.; Zimmer, Y.; Medová, M. A Comparative Analysis of Individual RAS Mutations in Cancer Biology. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, A.M.; Perry, M.A.; Chou, J.F.; Nandakumar, S.; Muldoon, D.; Erakky, A.; Zucker, A.; Fong, C.; Mehine, M.; Nguyen, B.; et al. Clinicogenomic Landscape of Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Identifies KRAS Mutant Dosage as Prognostic of Overall Survival. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timar, J.; Kashofer, K. Molecular Epidemiology and Diagnostics of KRAS Mutations in Human Cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, J.; Bowcut, V.; Calinisan, A.; Briere, D.M.; Hargis, L.; Engstrom, L.D.; Laguer, J.; Medwid, J.; Vanderpool, D.; Lifset, E.; et al. Anti-Tumor Efficacy of a Potent and Selective Non-Covalent KRASG12D Inhibitor. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2171–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinari, T.; Nagashima, T.; Ishioka, H.; Inamura, K.; Nishizono, Y.; Tasaki, M.; Iguchi, K.; Suzuki, A.; Sato, C.; Nakayama, A.; et al. Discovery of KRAS(G12D) Selective Degrader ASP3082. Commun. Chem. 2025, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilev, B.; Atanasova, M.; Vasilev, B.; Atanasova, M. A (Comprehensive) Review of the Application of Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship (QSAR) in the Prediction of New Compounds with Anti-Breast Cancer Activity. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropsha, A.; Isayev, O.; Varnek, A.; Schneider, G.; Cherkasov, A. Integrating QSAR Modelling and Deep Learning in Drug Discovery: The Emergence of Deep QSAR. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 23, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, M.J.; Arrowsmith, J.; Leach, A.R.; Leeson, P.D.; Mandrell, S.; Owen, R.M.; Pairaudeau, G.; Pennie, W.D.; Pickett, S.D.; Wang, J.; et al. An Analysis of the Attrition of Drug Candidates from Four Major Pharmaceutical Companies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Waterbeemd, H.; Gifford, E. ADMET in Silico Modelling: Towards Prediction Paradise? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003, 2, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wang, L.; Zuo, X.; Maitra, A.; Bresalier, R.S. A Small Molecule with Big Impact: MRTX1133 Targets the KRASG12D Mutation in Pancreatic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S.B.; Cheng, N.; Markosyan, N.; Sor, R.; Kim, I.K.; Hallin, J.; Shoush, J.; Quinones, L.; Brown, N.V.; Bassett, J.B.; et al. Efficacy of a Small-Molecule Inhibitor of KrasG12D in Immunocompetent Models of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Zeng, R.; Pan, M.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, H.; Shen, W.; Tang, Y.; Lei, P.; Mikov, M.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; et al. Pharmacokinetics, Bioavailability, and Tissue Distribution of MRTX1133 in Rats Using UHPLC-MS/MS. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1509319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bristol Exits KRAS G12D. ApexOnco—Clinical Trials News and Analysis. Available online: https://www.oncologypipeline.com/apexonco/bristol-exits-kras-g12d (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and Computational Approaches to Estimate Solubility and Permeability in Drug Discovery and Development Settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997, 23, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muegge, I.; Heald, S.L.; Brittelli, D. Simple Selection Criteria for Drug-like Chemical Matter. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 1841–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.K.; Viswanadhan, V.N.; Wendoloski, J.J. A Knowledge-Based Approach in Designing Combinatorial or Medicinal Chemistry Libraries for Drug Discovery. 1. A Qualitative and Quantitative Characterization of Known Drug Databases. J. Comb. Chem. 1998, 1, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veber, D.F.; Johnson, S.R.; Cheng, H.Y.; Smith, B.R.; Ward, K.W.; Kopple, K.D. Molecular Properties That Influence the Oral Bioavailability of Drug Candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, W.J.; Merz, K.M.; Baldwin, J.J. Prediction of Drug Absorption Using Multivariate Statistics. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3867–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenk, R.; Schipani, A.; James, D.; Krasowski, A.; Gilbert, I.H.; Frearson, J.; Wyatt, P.G. Lessons Learnt from Assembling Screening Libraries for Drug Discovery for Neglected Diseases. ChemMedChem 2008, 3, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baell, J.B.; Holloway, G.A. New Substructure Filters for Removal of Pan Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) from Screening Libraries and for Their Exclusion in Bioassays. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2719–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srisongkram, T.; Khamtang, P.; Weerapreeyakul, N. Prediction of KRASG12C Inhibitors Using Conjoint Fingerprint and Machine Learning-Based QSAR Models. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2023, 122, 108466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisongkram, T.; Weerapreeyakul, N. Drug Repurposing against KRAS Mutant G12C: A Machine Learning, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadee, P.; Prompat, N.; Yamabhai, M.; Sangkhathat, S.; Benjakul, S.; Tipmanee, V.; Saetang, J. In Silico Identification of Selective KRAS G12D Inhibitor via Machine Learning-Based Molecular Docking Combined with Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Adv. Theory Simul. 2024, 7, 2400489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, A.; Danial, M.; Zulfat, M.; Numan, M.; Zakir, S.; Hayat, C.; Alabbosh, K.F.; Zaki, M.E.A.; Ali, A.; Wei, D. In Silico Prediction of New Inhibitors for Kirsten Rat Sarcoma G12D Cancer Drug Target Using Machine Learning-Based Virtual Screening, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamic Simulation Approaches. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCED. Guidance Document on the Validation of (Quantitative) Structure-Activity Relationship [(Q)SAR] Models; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourches, D.; Muratov, E.; Tropsha, A. Trust, but Verify: On the Importance of Chemical Structure Curation in Cheminformatics and QSAR Modeling Research. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weininger, D. SMILES, a Chemical Language and Information System. 1. Introduction to Methodology and Encoding Rules. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2002, 28, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, D.; Gaulton, A.; Bento, A.P.; Chambers, J.; De Veij, M.; Félix, E.; Magariños, M.P.; Mosquera, J.F.; Mutowo, P.; Nowotka, M.; et al. ChEMBL: Towards Direct Deposition of Bioassay Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D930–D940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polishchuk, P.; Tinkov, O.; Khristova, T.; Ognichenko, L.; Kosinskaya, A.; Varnek, A.; Kuz’min, V. Structural and Physico-Chemical Interpretation (SPCI) of QSAR Models and Its Comparison with Matched Molecular Pair Analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016, 56, 1455–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Burns, A.C.; Christensen, J.G.; Ketcham, J.M.; Lawson, J.D.; Marx, M.A.; Smith, C.R.; Allen, S.; Blake, J.F.; Chicarelli, M.J.; et al. KRas G12D Inhibitors. U.S. Patent US11453683B1, 27 September 2022. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US11453683B1 (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Issahaku, A.R.; Mukelabai, N.; Agoni, C.; Rudrapal, M.; Aldosari, S.M.; Almalki, S.G.; Khan, J. Characterization of the Binding of MRTX1133 as an Avenue for the Discovery of Potential KRASG12D Inhibitors for Cancer Therapy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, V.M.; Bobrowski, T.; Melo-Filho, C.C.; Korn, D.; Auerbach, S.; Schmitt, C.; Muratov, E.N.; Tropsha, A. QSAR Modeling of SARS-CoV Mpro Inhibitors Identifies Sufugolix, Cenicriviroc, Proglumetacin, and Other Drugs as Candidates for Repurposing against SARS-CoV-2. Mol. Inform. 2021, 40, 2000113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi Vakili, M.; Gorgulla, C.; Snider, J.; Nigam, A.; Bezrukov, D.; Varoli, D.; Aliper, A.; Polykovsky, D.; Padmanabha Das, K.M.; Cox, H., III; et al. Quantum-Computing-Enhanced Algorithm Unveils Potential KRAS Inhibitors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, A.V.; Zhao, T.; Nguyen, D.-T.; Peryea, T.; Sheils, T.; Yasgar, A.; Huang, R.; Southall, N.; Simeonov, A. Novel Consensus Architecture To Improve Performance of Large-Scale Multitask Deep Learning QSAR Models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 4613–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedeck, P.; Rohde, B.; Bartels, C. QSAR—How Good Is It in Practice? Comparison of Descriptor Sets on an Unbiased Cross Section of Corporate Data Sets. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2006, 46, 1924–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Hwang, L.; Burley, S.K.; Nitsche, C.I.; Southan, C.; Walters, W.P.; Gilson, M.K. BindingDB in 2024: A FAIR Knowledgebase of Protein-Small Molecule Binding Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1633–D1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladinskiy, V.; Mantsyzov, A.B.; Kruse, C.; Noev, A.; Petrov, R.; Reshetnikov, V.; Shi, S.; Ding, X.; Cai, X.; Aliper, A.; et al. Identification of Novel Pan-KRAS Inhibitors via Structure-Based Drug Design, Scaffold Hopping, and Biological Evaluation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2025, 16, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RDKit. Available online: https://github.com/rdkit (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Yap, C.W. PaDEL-Descriptor: An Open Source Software to Calculate Molecular Descriptors and Fingerprints. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1466–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecrl/Padelpy: A Python Wrapper for PaDEL-Descriptor Software. Available online: https://github.com/ecrl/padelpy (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- CatBoost—Open-Source Gradient Boosting Library. Available online: https://catboost.ai/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Ash, J.R.; Wognum, C.; Rodríguez-Pérez, R.; Aldeghi, M.; Cheng, A.C.; Clevert, D.A.; Engkvist, O.; Fang, C.; Price, D.J.; Hughes-Oliver, J.M.; et al. Practically Significant Method Comparison Protocols for Machine Learning in Small Molecule Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 9398–9411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, V.M.; Capuzzi, S.J.; Braga, R.C.; Korn, D.; Hochuli, J.E.; Bowler, K.H.; Yasgar, A.; Rai, G.; Simeonov, A.; Muratov, E.N.; et al. SCAM Detective: Accurate Predictor of Small, Colloidally Aggregating Molecules. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 4056–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojala, M.; Garriga, G.C. Permutation Tests for Studying Classifier Performance. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2010, 11, 1833–1863. [Google Scholar]

- Shrikumar, A.; Greenside, P.; Kundaje, A. Learning Important Features through Propagating Activation Differences. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; Volume 7, pp. 4844–4866. [Google Scholar]

- Kier, L.B.; Hall, L.H. An Electrotopological-State Index for Atoms in Molecules. Pharm. Res. 1990, 7, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetko, I.V.; Tanchuk, V.Y. Application of Associative Neural Networks for Prediction of Lipophilicity in ALOGPS 2.1 Program. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2002, 42, 1136–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbeck, C.; Han, Y.; Kuhn, S.; Horlacher, O.; Luttmann, E.; Willighagen, E. The Chemistry Development Kit (CDK): An Open-Source Java Library for Chemo- and Bioinformatics. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003, 43, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, R.; Consonni, V. Handbook of Molecular Descriptors; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; p. 667. [Google Scholar]

- Thormann, M.; Vidal, D.; Almstetter, M.; Pons, M. Nomen Est Omen: Quantitative Prediction of Molecular Properties Directly from IUPAC Names. Open Appl. Inform. J. 2007, 1, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, D.; Hahn, M. Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlvaDesc—KNIME—Alvascience. Available online: https://www.alvascience.com/knime-alvadesc/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Varnek, A.; Fourches, D.; Hoonakker, F.; Solov’ev, V.P. Substructural Fragments: An Universal Language to Encode Reactions, Molecular and Supramolecular Structures. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2005, 19, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Xie, Q.; Ge, W.; Qian, F.; Fang, H.; Shi, L.; Su, Z.; Perkins, R.; Tong, W. Mold2, Molecular Descriptors from 2D Structures for Chemoinformatics and Toxicoinformatics. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2008, 48, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriwaki, H.; Tian, Y.S.; Kawashita, N.; Takagi, T. Mordred: A Molecular Descriptor Calculator. J. Chem. 2018, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 2016, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ma, J.; Liaw, A.; Sheridan, R.P.; Svetnik, V. Demystifying Multitask Deep Neural Networks for Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationships. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 2490–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itskowitz, P.; Tropsha, A. K Nearest Neighbors QSAR Modeling as a Variational Problem: Theory and Applications. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasulev, B.F.; Toropov, A.A.; Hamme, A.T.; Leszczynski, J. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis and Optimal Descriptors: Predicting the Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein Inhibition Activity. QSAR Comb. Sci. 2008, 27, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, P.; Godin, G.; Tetko, I.V. Transformer-CNN: Swiss Knife for QSAR Modeling and Interpretation. J. Cheminform. 2020, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Wang, D.; Liu, X.; Zhong, F.; Wan, X.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Luo, X.; Chen, K.; Jiang, H.; et al. Pushing the Boundaries of Molecular Representation for Drug Discovery with the Graph Attention Mechanism. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 63, 8749–8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heid, E.; Greenman, K.P.; Chung, Y.; Li, S.C.; Graff, D.E.; Vermeire, F.H.; Wu, H.; Green, W.H.; McGill, C.J. Chemprop: A Machine Learning Package for Chemical Property Prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 64, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCHEM Introduction—OCHEM User’s Manual—OCHEM Docs. Available online: https://docs.ochem.eu/display/MAN.html (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array Programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mckinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McNutt, A.T.; Li, Y.; Meli, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Koes, D.R. GNINA 1.3: The next Increment in Molecular Docking with Deep Learning. J. Chem. 2025, 17, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carato, P.; Oxombre, B.; Ravez, S.; Boulahjar, R.; Donnier-Maréchal, M.; Barczyk, A.; Liberelle, M.; Vermersch, P.; Melnyk, P. Discovery of Novel Benzamide-Based Sigma-1 Receptor Agonists with Enhanced Selectivity and Safety. Molecules 2025, 30, 3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Han, J.; Xu, Y.; Pandit, A.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, M.; Liu, C.; et al. PoseX: AI Defeats Physics-Based Methods on Protein Ligand Cross-Docking 2025. In Proceedings of the Thirty-ninth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 2–7 December 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Macip, G.; Garcia-Segura, P.; Mestres-Truyol, J.; Saldivar-Espinoza, B.; Ojeda-Montes, M.J.; Gimeno, A.; Cereto-Massagué, A.; Garcia-Vallvé, S.; Pujadas, G. Haste Makes Waste: A Critical Review of Docking-Based Virtual Screening in Drug Repurposing for SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (M-pro) Inhibition. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 744–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PatWalters/Useful_rdkit_utils: Some Useful RDKit Functions. Available online: https://github.com/PatWalters/useful_rdkit_utils (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Ehrt, C.; Schulze, T.; Graef, J.; Diedrich, K.; Pletzer-Zelgert, J.; Rarey, M. ProteinsPlus: A Publicly Available Resource for Protein Structure Mining. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, W478–W484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Descriptors | Algorithms | Training Set, 5-Fold CV | Test Set | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Compounds | Cov | AD Compounds | ||||||

| RMSE | RMSE | RMSE | ||||||

| Topological Torsion fingerprints | CatBoost | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.74 |

| SVM | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.74 | ||

| MLP | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.79 | 0.55 | 0.79 | ||

| MACCS | CatBoost | 0.48 | 0.88 | 0.46 | 0.91 | 0.67 | 0.37 | 0.97 |

| SVM | 0.48 | 0.88 | 0.46 | 0.91 | 0.37 | 0.98 | ||

| MLP | 0.44 | 0.91 | 0.44 | 0.93 | 0.36 | 0.99 | ||

| PubChem | CatBoost | 0.58 | 0.79 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.75 |

| SVM | 0.60 | 0.78 | 0.60 | 0.78 | 0.49 | 0.85 | ||

| MLP | 0.57 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 0.78 | 0.51 | 0.81 | ||

| KlekotaRoth | CatBoost | 0.62 | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.72 |

| SVM | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.74 | ||

| MLP | 0.50 | 0.86 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.75 | ||

| Atom Pairs fingerprints | CatBoost | 0.57 | 0.80 | 0.53 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 0.87 |

| SVM | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 0.79 | ||

| MLP | 0.57 | 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.79 | 0.58 | 0.82 | ||

| ECFP4 | CatBoost | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.78 | 0.66 | 0.70 |

| SVM | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.70 | ||

| MLP | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.74 | ||

| Topological Path-Based fingerprints | CatBoost | 0.60 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.70 |

| SVM | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.76 | ||

| MLP | 0.54 | 0.82 | 0.58 | 0.80 | 0.56 | 0.81 | ||

| RDKit | CatBoost | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.71 |

| SVM | 0.60 | 0.77 | 0.58 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 0.76 | ||

| MLP | 0.51 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.86 | 0.53 | 0.85 | ||

| Consensus (ECFP4 + Topological Path-Based fingerprints + RDKit) | CatBoost | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.70 | 0.66 |

| # | Molecular Transformations and SMIRKS | # MT | ΔMean | An Example of a Molecular Transformation (Molecular Pair) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reducing Inhibitory Activity | ||||

| 1 |  [O] * -> * C#N | 8 | −2.0 ± 0.85 |  pIC50 = 9.30 pIC50 = 7.69 |

| 2 |  [C][C] * -> [C]O * | 5 | −1.9 ± 1.0 |  pIC50 = 8.96 pIC50 = 7.60 |

| 3 |  [C]N1[C][C][C][C@H]1 * -> [C]c1[c][c]c(*)n[c]1 | 5 | −1.5 ± 0.23 |  pIC50 = 8.57 pIC50 = 6.81 |

| 4 |  [O] * -> [C]O * | 9 | −1.4 ± 1.5 |  pIC50 = 9.40 pIC50 = 5.57 |

| 5 |  [C][C] * -> * C#N | 4 | −1.4 ± 0.63 |  pIC50 = 8.96 pIC50 = 7.69 |

| Increasing inhibitory activity | ||||

| 6 |  * [C][C] * -> * [C]C12[C][C][C]N1[C](*)[C][C]2 | 6 | 25 ± 0.22 |  pIC50 = 5.30 pIC50 = 8.12 |

| 7 |  * c1[c][c]c(*)[c][c]1 -> [O]c1[c]c(*)[c]c(*)[c]1 | 4 | 2.0 ± 0.2 |  pIC50 = 6.71 pIC50 = 8.82 |

| 8 |  * c1[c][c]n[c][c]1 -> [C]c1n[c][c]n1[C] * | 4 | 1.8 ± 0.36 |  pIC50 = 5.82 pIC50 = 8.02 |

| 9 |  * c1[c][c]c(*)[c][c]1 -> * [C]1[C][C](*)c2[c][c][c][c]c2[C]1 | 11 | 1.8 ± 1.0 |  pIC50 = 5.79 pIC50 = 9.30 |

| 10 |  * c1[c][c]n[c][c]1 -> [C]c1n[c][c]n1[C] * | 4 | 1.6 ± 0.3 |  pIC50 = 6.18 pIC50 = 8.02 |

| Parameters | MRTX1133 | Compound 2 | Compound 3 | Muegge Rules |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight(MW), Da | 600.7 | 514.6 | 499.5 | 200–600 |

| Octanol-water coefficient(LogP) | 4.71 | 3.47 | 3.88 | ≤5 |

| Number of hydrogen bond donors (HBD) | 2 | 2 | 2 | ≤5 |

| Number of hydrogen bond acceptors(HBAs) | 8 | 8 | 7 | ≤10 |

| Number of rotatable bonds | 5 | 5 | 4 | ≤15 |

| Topological polar surface area (TPSA), Å2 | 86.64 | 86.64 | 99.52 | ≤150 |

| Number of rings | 8 | 7 | 5 | ≤7 |

| Compound | pIC50, * Experimental Data | Affinity, kcal/mol | Intra, kcal/mol | CNN Pose Score | CNN Affinity, pK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDBM573509 | 5.57 * | −10.51 | −0.34 | 0.6809 | 8.134 |

| compound 1 | 7.98 | −11.81 | −0.91 | 0.7935 | 8.193 |

| compound 2 | 8.05 | −11.70 | −0.87 | 0.7585 | 8.094 |

| compound 3 | 7.49 | −8.44 | 3.64 | 0.6612 | 7.348 |

| MRTX1133 | 8.25 ± 0.47 * | −13.55 | −0.55 | 0.8120 | 8.554 |

| Parameter for Comparison | Panik et al. [30] | Ajmal et al. [31] | This Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of developed QSAR models | Binary classification | Binary classification | Regression |

| Description of the experimental data preprocessing procedure in accordance with mandatory requirements [33] | No | No | Yes |

| Molecular descriptors | PubChem | 2D MOE | ECFP4, Klekota-Roth, PubChem, MACCS, Topological Torsion, Atom Pairs, Topological Path-Based fingerprints, RDKit, OEState, ALogPS, CDK, Dragon, QNPR, alvaDesc, Fragmentor, MOLD2, MORDRED |

| Machine learning methods | Random forest, k-nearest neighbors, support vector machine, XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost | Random forest, k-nearest neighbors, support vector machine | Random forest, k-nearest neighbors, support vector machine, XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost, Multilayered perceptron, deep neural network, associative neural networks, multiple linear regression analysis, transformer convolutional neural network, Attentive FP, Chemprop |

| Definition of the applicability domain —the third mandatory principle of QSAR modeling according to OECD [32] | No | No | Yes |

| Structural interpretation—the fifth recommended principle of QSAR modeling according to OECD [32] | No | No | Yes |

| Application of y-randomization for the identification of chance correlation | No | No | Yes |

| Form of QSAR model implementation | No | No | Jupyter Notebook, executable via Google Colab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tinkov, O.V.; Gurevich, P.E.; Nikolenko, S.A.; Kadyrov, S.D.; Bogatyreva, N.S.; Grigorev, V.Y.; Ivankov, D.N.; Pak, M.A. KRASAVA—An Expert System for Virtual Screening of KRAS G12D Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010120

Tinkov OV, Gurevich PE, Nikolenko SA, Kadyrov SD, Bogatyreva NS, Grigorev VY, Ivankov DN, Pak MA. KRASAVA—An Expert System for Virtual Screening of KRAS G12D Inhibitors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010120

Chicago/Turabian StyleTinkov, Oleg V., Pavel E. Gurevich, Sergei A. Nikolenko, Shamil D. Kadyrov, Natalya S. Bogatyreva, Veniamin Y. Grigorev, Dmitry N. Ivankov, and Marina A. Pak. 2026. "KRASAVA—An Expert System for Virtual Screening of KRAS G12D Inhibitors" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010120

APA StyleTinkov, O. V., Gurevich, P. E., Nikolenko, S. A., Kadyrov, S. D., Bogatyreva, N. S., Grigorev, V. Y., Ivankov, D. N., & Pak, M. A. (2026). KRASAVA—An Expert System for Virtual Screening of KRAS G12D Inhibitors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010120