Targeting the Glutaminolysis Pathway in Glaucoma-Associated Fibrosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Glaucoma

1.2. Fibrosis

1.3. Various Cell Types Associated with Fibrosis

1.4. Mechanism of Fibrosis

1.5. Similarities Between Fibrosis and Cancer

2. Metabolic Reprogramming in Fibrosis and Cancer

2.1. Metabolic Reprogramming in Fibrosis

2.2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

2.3. Need for Metabolic Reprogramming Due to Increased Energy Demands

2.4. Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer

2.5. Metabolic Manipulation of Cell Death and Apoptosis

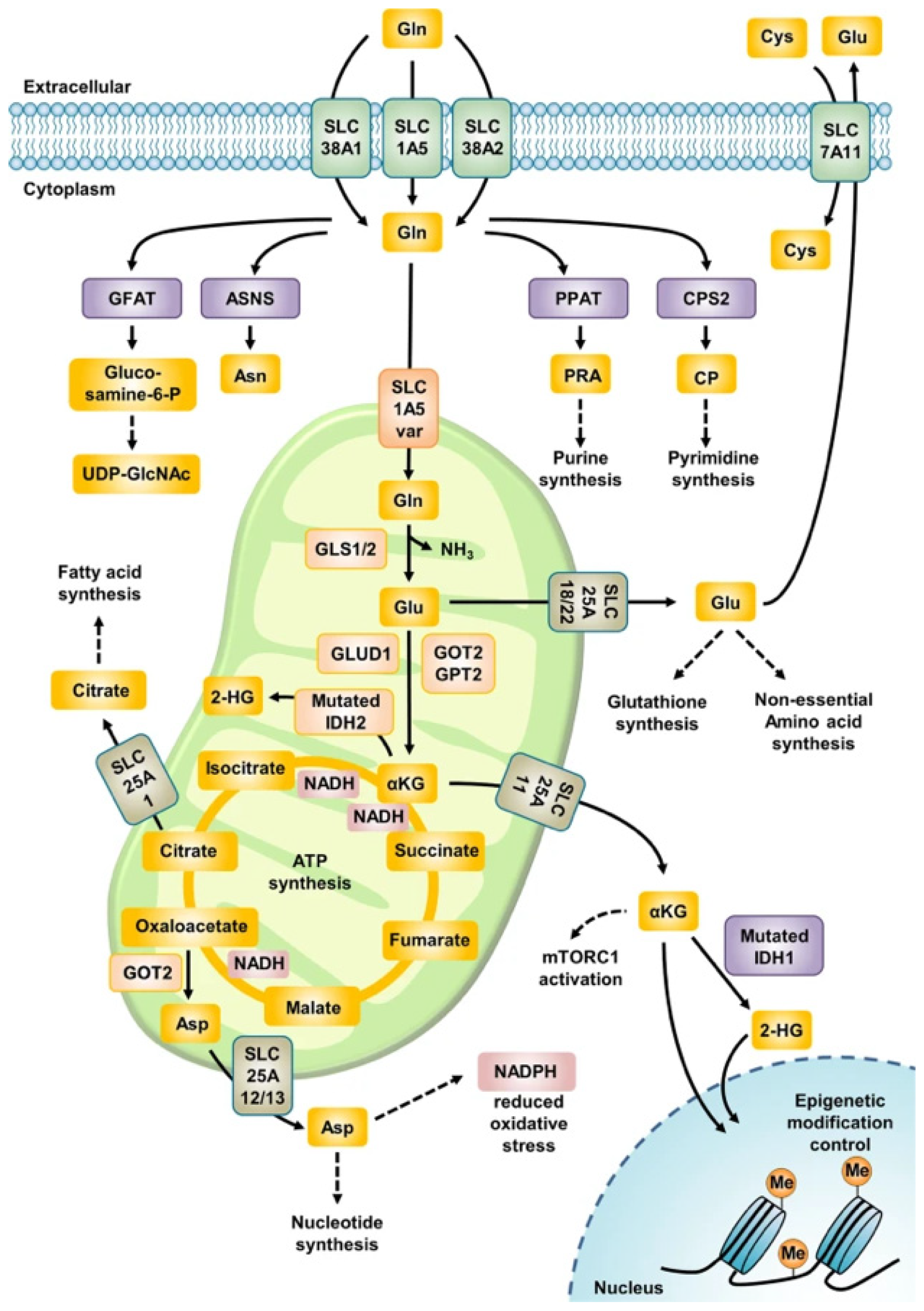

3. Glutaminolysis

3.1. Glutamine

3.2. The Common Pathway in Glutaminolysis

3.3. The Glutaminase II Pathway

3.4. Nucleotide Synthesis Associated with Glutaminolysis

3.5. Neurodegeneration

4. Glutaminolysis in Oncology

4.1. The Role of Glutaminase 1

4.2. The Role of Glutaminase 2

4.3. Centromere Protein A as a Critical Transcription Factor

4.4. Activating Transcription Factor 4 and Its Role in Glutaminolysis and Oncology

5. Glutaminolysis in Specific Systemic Fibrotic Diseases

5.1. Overview

5.2. Glutaminolysis in Cirrhosis

5.3. Glutaminolysis in Respiratory Fibrosis

5.4. Glutaminolysis in Other Fibrotic Diseases

6. Glutaminolysis in the Eye

6.1. Glutaminolysis in the Cornea

6.2. Glutaminolysis in the Lens

6.3. Glutaminolysis in Ocular Diseases

7. The Important Fibrogenic Signalling Pathways Associated with Glutaminolysis

7.1. Transforming Growth Factor-Beta

7.2. MAPK Pathways

7.3. Energy Production Signalling

8. Targeting Glutaminolysis in Cancer and Fibrosis

8.1. Glutamine Antagonists

8.2. Telaglenastat

8.3. Novel Therapies

| Therapeutic Mechanism | Drug/Molecular Target | References |

|---|---|---|

| Glutamine Antagonists | DON | Lemberg et al., 2018 [170] |

| Lye et al., 2023 [171] | ||

| Leone et al., 1979 [172] | ||

| Acivicin | Kreuzer et al., 2015 [173] | |

| Olver et al., 1998 [174] | ||

| Azaserine | Lyons et al., 1990 [175] | |

| Glutamine Transporters | SLC1A5 (ASCT2) | Lye et al., 2023 [171] |

| Kawakami et al., 2022 [176] | ||

| Esslinger et al., 2005 [177] | ||

| Chiu et al., 2017 [178] | ||

| SLC38A1 (SNAT1) | Jalota et al., 2025; Liu et al. 2024 [179,180] | |

| Zavorka Thomas et al., 2021 [181] | ||

| SLC38A2 (SNAT2) | Koe et al., 2025; Gauthier-Coles et al., 2022 [182,183] | |

| SLC6A14 | Lu et al., 2022; Su et al., 2025; Coothankandaswamy et al., 2016 [184,185,186] | |

| Glutaminolysis Enzyme Inhibitors | GLS1 | Ramachandran et al., 2016 [187] |

| Zimmermann et al., 2016 [188] | ||

| Momcilovic et al., 2017 [189] | ||

| Raczka and Reynolds, 2019 [190] | ||

| Thompson et al., 2017 [191] | ||

| GLS2 | Lukey et al., 2019 [192] | |

| Glutaminase C | Katt et al., 2012 [153] |

9. Fibrosis in Glaucoma

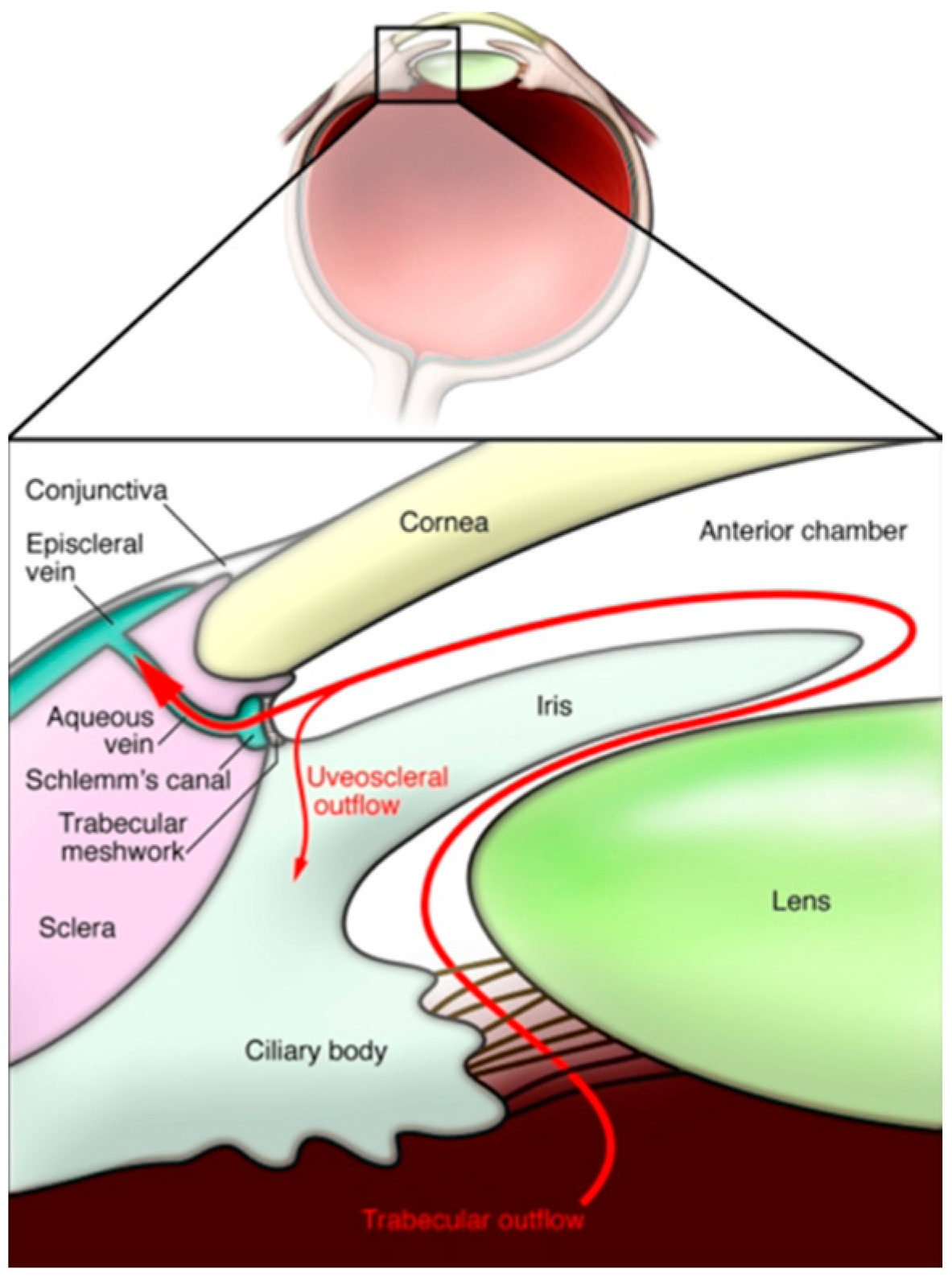

9.1. The Pathophysiology of Glaucoma and the Importance of Intraocular Pressure

9.2. Fibrosis in the Trabecular Meshwork

9.3. Fibrosis in the Schlemm’s Canal

9.4. Fibrosis in the Lamina Cribrosa

9.5. Glaucomatous Fibrosis and TGF-β

| Ocular Tissue Type | References | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Trabecular Meshwork | Tamm et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2025; [203,206] | Increased accumulation of banded fibrillar elements derived from juxtacanalicular tissue. Increased deposition of FN-EDA fibronectin fibrils |

| Trabecular Meshwork | Callaghan et al., 2022 [204] | Treating cells with TGF-β induces the upregulation of profibrotic gene expression across a genome-wide transcriptome. |

| Trabecular Meshwork | Last et al., 2011; Keller et al., 2018 [202,224] | Mean elastic modulus of glaucomatous TM cells is significantly increased, leading to increased extracellular matrix stiffness |

| Schlemm’s Canal | Kelly et al., 2021. [208] | Increased actin stress fibres and density of F-actin cytoskeletal protein expression |

| Schlemm’s Canal | Kelly et al., 2021 [208] | Increased cell size and proliferation in glaucomatous SC endothelial cells |

| Schlemm’s Canal | Overby et al., 2014 [209] | Increased cytoskeletal stiffness of SC endothelial cells |

| Lamina Cribrosa | Hernandez et Ye, 1993; Liu et al., 2018 [194,211] | Increased collagen type IV mRNA. Increased actin filament development and vinculin-focal adhesion formation. |

| Lamina Cribrosa | Kirwan et al., 2009 [210] | ECM is remodelled and demonstrates increased profibrotic gene expression |

| Lamina Cribrosa | Zeimer et al., 1989 [219] | Stiffer, more fibrotic LC in glaucoma |

10. Glutaminolysis in Glaucoma

10.1. Current Literature

10.2. Glutaminolysis, Neurodegeneration and Glaucoma

10.3. Potential Therapeutic Targets

10.4. Future Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, Y.; Chen, A.; Zou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, L.; Li, Y.; Zheng, D.; Jin, G.; Congdon, N. Time trends, associations and prevalence of blindness and vision loss due to glaucoma: An analysis of observational data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e053805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, J.D.; Khawaja, A.P.; Weizer, J.S. Glaucoma in Adults—Screening, Diagnosis, and Management: A Review. JAMA 2021, 325, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, Y.-C.; Li, X.; Wong, T.Y.; Quigley, H.A.; Aung, T.; Cheng, C.-Y. Global Prevalence of Glaucoma and Projections of Glaucoma Burden through 2040. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, C.; Chen, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, W. Factors associated with delayed first ophthalmological consultation for primary glaucoma: A qualitative interview study. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1161980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarieh, M.; Fraenkl, S.; Konieczka, K.; Flammer, J. Targeted preventive measures and advanced approaches in personalised treatment of glaucoma neuropathy. EPMA J. 2010, 1, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Reynaud, J.; Lockwood, H.; Williams, G.; Hardin, C.; Reyes, L.; Stowell, C.; Gardiner, S.K.; Burgoyne, C.F. The connective tissue phenotype of glaucomatous cupping in the monkey eye-Clinical and research implications. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017, 59, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.R.; Andrzejewska, W.M.; Neufeld, A.H. Changes in the Extracellular Matrix of the Human Optic Nerve Head in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1990, 109, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamm, E.R.; Ethier, C.R.; Dowling, J.E.; Downs, C.; Ellisman, M.H.; Fisher, S.; Fortune, B.; Fruttiger, M.; Jakobs, T.; Lewis, G.; et al. Biological aspects of axonal damage in glaucoma: A brief review. Exp. Eye Res. 2017, 157, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynn, T.A. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J. Pathol. 2008, 214, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, B. Formation and Function of the Myofibroblast during Tissue Repair. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2007, 127, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasek, J.J.; Gabbiani, G.; Hinz, B.; Chaponnier, C.; Brown, R.A. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataller, R.; Brenner, D.A. Liver fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; Zeisberg, M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sziksz, E.; Pap, D.; Lippai, R.; Béres, N.J.; Fekete, A.; Szabó, A.J.; Vannay, Á. Fibrosis Related Inflammatory Mediators: Role of the IL-10 Cytokine Family. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 764641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, E. Targeting monocytes/macrophages in fibrosis and cancer diseases: Therapeutic approaches. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 234, 108031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Sinha, M.; Datta, S.; Abas, M.; Chaffee, S.; Sen, C.K.; Roy, S. Monocyte and Macrophage Plasticity in Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 2596–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapouri-Moghaddam, A.; Mohammadian, S.; Vazini, H.; Taghadosi, M.; Esmaeili, S.-A.; Mardani, F.; Seifi, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Afshari, J.T.; Sahebkar, A. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 6425–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, S.T. Cells in Fibrosis and Fibrotic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A. Fibrotic disease and the TH1/TH2 paradigm. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevers, T.; Salvador, A.M.; Velazquez, F.; Ngwenyama, N.; Carrillo-Salinas, F.J.; Aronovitz, M.; Blanton, R.M.; Alcaide, P. Th1 effector T cells selectively orchestrate cardiac fibrosis in nonischemic heart failure. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 3311–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barron, L.; Wynn, T.A. Fibrosis is regulated by Th2 and Th17 responses and by dynamic interactions between fibroblasts and macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2011, 300, G723–G728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tredget, E.E.; Yang, L.; Delehanty, M.; Shankowsky, H.; Scott, P.G. Polarized Th2 Cytokine Production in Patients with Hypertrophic Scar Following Thermal Injury. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006, 26, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, J.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, D. New insights into fibrosis from the ECM degradation perspective: The macrophage-MMP-ECM interaction. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 117, Erratum in: Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanos, N.K.; Theocharis, A.D.; Piperigkou, Z.; Manou, D.; Passi, A.; Skandalis, S.S.; Vynios, D.H.; Orian-Rousseau, V.; Ricard-Blum, S.; Schmelzer, C.E.; et al. A guide to the composition and functions of the extracellular matrix. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 6850–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, L.; Stalfort, J.; Barker, T.H.; Abebayehu, D. The interplay of fibroblasts, the extracellular matrix, and inflammation in scar formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 298, 101530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landolt, L.; Spagnoli, G.C.; Hertig, A.; Brocheriou, I.; Marti, H.-P. Fibrosis and cancer: Shared features and mechanisms suggest common targeted therapeutic approaches. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2022, 37, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybinski, B.; Franco-Barraza, J.; Cukierman, E. The wound healing, chronic fibrosis, and cancer progression triad. Physiol. Genom. 2014, 46, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockey, D.C.; Bell, P.D.; A Hill, J. Fibrosis—A Common Pathway to Organ Injury and Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1138–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Espín, D.; Serrano, M. Cellular senescence: From physiology to pathology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; Weinberg, R.A. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovisa, S.; LeBleu, V.S.; Tampe, B.; Sugimoto, H.; Vadnagara, K.; Carstens, J.L.; Wu, C.-C.; Hagos, Y.; Burckhardt, B.C.; Pentcheva-Hoang, T.; et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition induces cell cycle arrest and parenchymal damage in renal fibrosis. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitoh, M. Involvement of partial EMT in cancer progression. J. Biochem. 2018, 164, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landolt, L.; Furriol, J.; Babickova, J.; Ahmed, L.; Eikrem, Ø.; Skogstrand, T.; Scherer, A.; Suliman, S.; Leh, S.; Lorens, J.B.; et al. AXL targeting reduces fibrosis development in experimental unilateral ureteral obstruction. Physiol. Rep. 2019, 7, e14091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Sharma, A.; Patne, K.; Tabasum, S.; Suryavanshi, J.; Rawat, L.; Machaalani, M.; Eid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Choueiri, T.K.; et al. AXL signaling in cancer: From molecular insights to targeted therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, S.Y.; Vander Heiden, M.G. Aerobic Glycolysis: Meeting the Metabolic Requirements of Cell Proliferation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011, 27, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewitson, T.D.; Smith, E.R. A Metabolic Reprogramming of Glycolysis and Glutamine Metabolism Is a Requisite for Renal Fibrogenesis—Why and How? Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 645857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.W.; Chan, N.C.; A Sadun, A. Glaucoma as Neurodegeneration in the Brain. Eye Brain 2021, 13, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trelford, C.B.; Denstedt, J.T.; Armstrong, J.J.; Hutnik, C.M. The Pro-Fibrotic Behavior of Human Tenon’s Capsule Fibroblasts in Medically Treated Glaucoma Patients. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 14, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamanaka, R.B.; O’leary, E.M.; Witt, L.J.; Tian, Y.; Gökalp, G.A.; Meliton, A.Y.; Dulin, N.O.; Mutlu, G.M. Glutamine Metabolism Is Required for Collagen Protein Synthesis in Lung Fibroblasts. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 61, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; Baba, S.K.; Khan, I.R.; Khan, M.S.; Husain, F.M.; Ahmad, S.; Haris, M.; Singh, M.; Akil, A.S.A.; Macha, M.A.; et al. Glutamine Metabolism: Molecular Regulation, Biological Functions, and Diseases. Medcomm 2025, 6, e70120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamanaka, R.B.; Mutlu, G.M. The role of metabolic reprogramming and de novo amino acid synthesis in collagen protein production by myofibroblasts: Implications for organ fibrosis and cancer. Amino Acids 2021, 53, 1851–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Cao, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Xu, L.; Zhuang, Q. Mitochondrial dysfunction in fibrotic diseases. Cell Death Discov. 2020, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boengler, K.; Kosiol, M.; Mayr, M.; Schulz, R.; Rohrbach, S. Mitochondria and ageing: Role in heart, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. J. Cachex-Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan Dunn, J.; Alvarez, L.A.; Zhang, X.; Soldati, T. Reactive oxygen species and mitochondria: A nexus of cellular homeostasis. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Tan, Z.; Banerjee, S.; Cui, H.; Ge, J.; Liu, R.-M.; Bernard, K.; Thannickal, V.J.; Liu, G. Glycolytic Reprogramming in Myofibroblast Differentiation and Lung Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1462–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Jiang, L.; Xu, J.; Bai, F.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Luo, J.; Zen, K.; Yang, J. Inhibiting aerobic glycolysis suppresses renal interstitial fibroblast activation and renal fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2017, 313, F561–F575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruzat, V.; Macedo Rogero, M.; Keane, K.N.; Curi, R.; Newsholme, P. Glutamine: Metabolism and Immune Function, Supplementation and Clinical Translation. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesi, S.B.; Fisher, J.H.; Martinez, F.J.; Selman, M.; Pardo, A.; Johannson, K.A. Update in Interstitial Lung Disease 2019. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, K.; Chitneni, S.K.; Suzuki, A.; Wang, Y.; Henao, R.; Hyun, J.; Premont, R.T.; Naggie, S.; Moylan, C.A.; Bashir, M.R.; et al. Increased Glutaminolysis Marks Active Scarring in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Progression. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarsenova, M.; Lawarde, A.; Pathare, A.D.S.; Saare, M.; Modhukur, V.; Soplepmann, P.; Terasmaa, A.; Käämbre, T.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K.; Lalitkumar, P.G.L.; et al. Endometriotic lesions exhibit distinct metabolic signature compared to paired eutopic endometrium at the single-cell level. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirrah, I.N.; Lokanathan, Y.; Zulkiflee, I.; Wee, M.F.M.R.; Motta, A.; Fauzi, M.B. A Comprehensive Review on Collagen Type I Development of Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering: From Biosynthesis to Bioscaffold. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, M.; Newport, E.; Morten, K.J. The Warburg effect: 80 years on. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvorak, H.F. Tumors: Wounds That Do Not Heal. N. Engl. J. Med. 1986, 315, 1650–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, K.P.; Maćkowska-Kędziora, A.; Sobolewski, B.; Woźniak, P. Key Roles of Glutamine Pathways in Reprogramming the Cancer Metabolism. Oxidative Med. Cell Longev. 2015, 2015, 964321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBerardinis, R.J.; Sayed, N.; Ditsworth, D.; Thompson, C.B. Brick by brick: Metabolism and tumor cell growth. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2008, 18, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, H.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, T. Expression of glutaminase is upregulated in colorectal cancer and of clinical significance. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fuller, G.G.; Kim, J.K. Compartmentalization and metabolic regulation of glycolysis. J. Cell Sci. 2021, 134, jcs258469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.P.; Sabatini, D.M. Cancer Cell Metabolism: Warburg and Beyond. Cell 2008, 134, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenzweig, A.; Blenis, J.; Gomes, A.P. Beyond the Warburg Effect: How Do Cancer Cells Regulate One-Carbon Metabolism? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.C.; Maddocks, O.D.K. One-carbon metabolism in cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducker, G.S.; Chen, L.; Morscher, R.J.; Ghergurovich, J.M.; Esposito, M.; Teng, X.; Kang, Y.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Reversal of Cytosolic One-Carbon Flux Compensates for Loss of the Mitochondrial Folate Pathway. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1140–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducker, G.S.; Rabinowitz, J.D. One-Carbon Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ser, Z.; Gao, X.; Johnson, C.; Mehrmohamadi, M.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Locasale, J.W. Targeting One Carbon Metabolism with an Antimetabolite Disrupts Pyrimidine Homeostasis and Induces Nucleotide Overflow. Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakkadath, M.; Naidu, D.; Kanthlal, S.K.; Sharun, K. Combating Methotrexate Resistance in Cancer Treatment: A Review on Navigating Pathways and Enhancing Its Efficacy with Fat-Soluble Vitamins. Scientifica 2025, 2025, 8259470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, J.H.-C. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in wound healing: Force generation and measurement. J. Tissue Viability 2011, 20, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, B.; Lagares, D. Evasion of apoptosis by myofibroblasts: A hallmark of fibrotic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Sparks, H.D.; Labit, E.; Robbins, H.N.; Gowing, K.; Jaffer, A.; Kutluberk, E.; Arora, R.; Raredon, M.S.B.; Cao, L.; et al. Fibroblast inflammatory priming determines regenerative versus fibrotic skin repair in reindeer. Cell 2022, 185, 4717–4736.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, A.S.; Phan, T.T.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Lim, H.Y.; Halliwell, B.; Wong, K.P. Human Skin Keloid Fibroblasts Display Bioenergetics of Cancer Cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Ko, B.; Hensley, C.T.; Jiang, L.; Wasti, A.T.; Kim, J.; Sudderth, J.; Calvaruso, M.A.; Lumata, L.; Mitsche, M.; et al. Glutamine Oxidation Maintains the TCA Cycle and Cell Survival during Impaired Mitochondrial Pyruvate Transport. Mol. Cell 2014, 56, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.H.; Cha, H.-J.; Lee, H.; Hong, S.-H.; Park, C.; Park, S.-H.; Kim, G.-Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.-S.; Hwang, H.-J.; et al. Protective Effect of Glutathione against Oxidative Stress-induced Cytotoxicity in RAW 264.7 Macrophages through Activating the Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor-2/Heme Oxygenase-1 Pathway. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, L.-P.; Liu, Y.-J.; Qiu, S.-T.; Yang, C.; Tang, J.-X.; Li, X.-Y.; Liu, H.-F.; Ye, Z.-N. Glutaminolysis is a Potential Therapeutic Target for Kidney Diseases. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2024, 17, 2789–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz, D. Glutaminolysis gets the spotlight in cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 10761–10762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Venneti, S.; Nagrath, D. Glutaminolysis: A Hallmark of Cancer Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 19, 163–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.C.; Yu, Y.C.; Sung, Y.; Han, J.M. Glutamine reliance in cell metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1496–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.J.L.; Dorai, T.; Pinto, J.T.; Denton, T.T. Metabolic Heterogeneity, Plasticity, and Adaptation to “Glutamine Addiction” in Cancer Cells: The Role of Glutaminase and the GTωA [Glutamine Transaminase—ω-Amidase (Glutaminase II)] Pathway. Biology 2023, 12, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A.J.L.; Shurubor, Y.I.; Dorai, T.; Pinto, J.T.; Isakova, E.P.; Deryabina, Y.I.; Denton, T.T.; Krasnikov, B.F. ω-Amidase: An underappreciated, but important enzyme in l-glutamine and l-asparagine metabolism; relevance to sulfur and nitrogen metabolism, tumor biology and hyperammonemic diseases. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 1–20, Erratum in: Amino Acids 2015, 47, 2671–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.M. Glutamine-dependent carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase and other enzyme activities related to the pyrimidine pathway in spleen of Squalus acanthias (spiny dogfish). Biochem. J. 1989, 261, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ren, W.; Huang, X.; Deng, J.; Li, T.; Yin, Y. Potential Mechanisms Connecting Purine Metabolism and Cancer Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Pavlova, N.N.; Thompson, C.B. Cancer cell metabolism: The essential role of the nonessential amino acid, glutamine. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 1302–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, L.B.; Gui, D.Y.; Hosios, A.M.; Bush, L.N.; Freinkman, E.; Vander Heiden, M.G. Supporting Aspartate Biosynthesis Is an Essential Function of Respiration in Proliferating Cells. Cell 2015, 162, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, B.S. Glutamate as a Neurotransmitter in the Brain: Review of Physiology and Pathology. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1007S–1015S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Hua, Z.; Li, Z. The role of glutamate and glutamine metabolism and related transporters in nerve cells. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohmadi, N.H.; Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Albuhadily, A.K.; Abdelaziz, A.M.; Jabir, M.S.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M.; Batiha, G.E.-S. Glutamatergic dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases focusing on Parkinson’s disease: Role of glutamate modulators. Brain Res. Bull. 2025, 225, 111349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, T.; Baskerville, R.; Rogero, M.; Castell, L. Emerging Evidence for the Widespread Role of Glutamatergic Dysfunction in Neuropsychiatric Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasoni, Z.; Bono, F.; Sbrini, G.; Guglielmi, A.; Mutti, V.; Mingardi, J.; Musazzi, L.; Filippini, A.; Ferraboli, S.; Missale, C.; et al. Dysregulation of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons in Treatment-Resistant Depression: Insights from patient-derived neurons. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 142, 111527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldyrev, A.; Bulygina, E.; Makhro, A. Glutamate receptors modulate oxidative stress in neuronal cells. A mini-review. Neurotox. Res. 2004, 6, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, D.R.; Newhouse, J.P. The Toxic Effect of Sodium L-Glutamate on the Inner Layers of the Retina. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1957, 58, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N.S.; Pascoe, C.J.; Giardina, S.F.; A John, C.; Beart, P.M. Micromolar l-glutamate induces extensive apoptosis in an apoptotic-necrotic continuum of insult-dependent, excitotoxic injury in cultured cortical neurones. Neuropharmacology 1998, 37, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.-L.; Gong, X.-X.; Qin, Z.-H.; Wang, Y. Molecular mechanisms of excitotoxicity and their relevance to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases—An update. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2025, 46, 3129–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, L.; Mou, J.; Shao, B.; Wei, Y.; Liang, H.; Takano, N.; Semenza, G.L.; Xie, G. Glutaminase 1 expression in colorectal cancer cells is induced by hypoxia and required for tumor growth, invasion, and metastatic colonization. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Guo, Y.; Seo, W.; Zhang, R.; Lu, C.; Wang, Y.; Luo, L.; Paul, B.; Yan, W.; Saxena, D.; et al. Targeting cellular metabolism to reduce head and neck cancer growth. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.; Guan, F.; Li, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Qin, Y.; Sun, Z.; Peng, S.; Cheng, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Glutaminase potentiates the glycolysis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by interacting with PDK1. Mol. Carcinog. 2024, 63, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, M.; Cao, J.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, L.; Shen, H.-M.; Xia, D. Epigenetic silencing of glutaminase 2 in human liver and colon cancers. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Jiménez, J.D.L.; Campos-Sandoval, J.A.; Rosales, T.; Ko, B.; Alonso, F.J.; Márquez, J.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Matés, J.M. Glutaminase-2 Expression Induces Metabolic Changes and Regulates Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Activity in Glioblastoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Mei, M.; Huang, Y. CENPA promotes glutamine metabolism and tumor progression by up-regulating SLC38A1 in endometrial cancer. Cell Signal. 2024, 117, 111110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuneva, M.; Zamboni, N.; Oefner, P.; Sachidanandam, R.; Lazebnik, Y. Deficiency in glutamine but not glucose induces MYC-dependent apoptosis in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 178, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anso, E.; Mullen, A.R.; Felsher, D.W.; Matés, J.M.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Chandel, N.S. Metabolic changes in cancer cells upon suppression of MYC. Cancer Metab. 2013, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Tchernyshyov, I.; Chang, T.-C.; Lee, Y.-S.; Kita, K.; Ochi, T.; Zeller, K.I.; De Marzo, A.M.; Van Eyk, J.E.; Mendell, J.T.; et al. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature 2009, 458, 762–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorén, M.M.; Vaapil, M.; Staaf, J.; Planck, M.; Johansson, M.E.; Mohlin, S.; Påhlman, S. Myc-induced glutaminolysis bypasses HIF-driven glycolysis in hypoxic small cell lung carcinoma cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 48983–48995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, D.R.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Mancuso, A.; Sayed, N.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Pfeiffer, H.K.; Nissim, I.; Daikhin, E.; Yudkoff, M.; McMahon, S.B.; et al. Myc regulates a transcriptional program that stimulates mitochondrial glutaminolysis and leads to glutamine addiction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 18782–18787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korangath, P.; Teo, W.W.; Sadik, H.; Han, L.; Mori, N.; Huijts, C.M.; Wildes, F.; Bharti, S.; Zhang, Z.; Santa-Maria, C.A.; et al. Targeting Glutamine Metabolism in Breast Cancer with Aminooxyacetate. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 3263–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Le, A.; Hancock, C.; Lane, A.N.; Dang, C.V.; Fan, T.W.-M.; Phang, J.M. Reprogramming of proline and glutamine metabolism contributes to the proliferative and metabolic responses regulated by oncogenic transcription factor c-MYC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8983–8988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, E.H.; Eberlin, L.S.; Dang, V.M.; Gouw, A.M.; Gabay, M.; Adam, S.J.; Bellovin, D.I.; Tran, P.T.; Philbrick, W.M.; Garcia-Ocana, A.; et al. MYC oncogene overexpression drives renal cell carcinoma in a mouse model through glutamine metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 6539–6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambay, V.; Raymond, V.-A.; Bilodeau, M. MYC Rules: Leading Glutamine Metabolism toward a Distinct Cancer Cell Phenotype. Cancers 2021, 13, 4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qie, S.; Yoshida, A.; Parnham, S.; Oleinik, N.; Beeson, G.C.; Beeson, C.C.; Ogretmen, B.; Bass, A.J.; Wong, K.-K.; Rustgi, A.K.; et al. Targeting glutamine-addiction and overcoming CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Koumenis, C. ATF4, an ER Stress and Hypoxia-Inducible Transcription Factor and its Potential Role in Hypoxia Tolerance and Tumorigenesis. Curr. Mol. Med. 2009, 9, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, B.; Liu, P.; Fang, S.; Yang, F.; You, Y.; Li, X. ATF4-dependent fructolysis fuels growth of glioblastoma multiforme. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Liu, H.; Mao, X.; Qin, Y.; Fan, C. ATF4 promotes lung cancer cell proliferation and invasion partially through regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 1442–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Zhang, P.; Liu, J.; Wang, R.; Kaufman, R.J.; Yaden, B.C.; Karin, M. ATF4 suppresses hepatocarcinogenesis by inducing SLC7A11 (xCT) to block stress-related ferroptosis. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Alfarsi, L.H.; El-Ansari, R.; Masisi, B.K.; Erkan, B.; Fakroun, A.; Ellis, I.O.; Rakha, E.A.; Green, A.R. ATF4 as a Prognostic Marker and Modulator of Glutamine Metabolism in Oestrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Pathobiology 2024, 91, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Yue, M.; Xiao, D.; Xiu, R.; Gan, L.; Liu, H.; Qing, G. ATF4 and N-Myc coordinate glutamine metabolism in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cells through ASCT2 activation. J. Pathol. 2015, 235, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Hwang, S.; Kim, B.; Shin, S.; Yang, S.; Gwak, J.; Jeong, S.M. YAP governs cellular adaptation to perturbation of glutamine metabolism by regulating ATF4-mediated stress response. Oncogene 2023, 42, 2828–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Liu, C. The ATF4-glutamine axis: A central node in cancer metabolism, stress adaptation, and therapeutic targeting. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.V.; Diehl, A.M. Liver Renewal: Detecting Misrepair and Optimizing Regeneration. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Hyun, J.; Premont, R.T.; Choi, S.S.; Michelotti, G.A.; Swiderska-Syn, M.; Dalton, G.D.; Thelen, E.; Rizi, B.S.; Jung, Y.; et al. Hedgehog-YAP Signaling Pathway Regulates Glutaminolysis to Control Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1465–1479.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.; Schaefbauer, K.J.; Kottom, T.J.; Yi, E.S.; Tschumperlin, D.J.; Limper, A.H. Targeting Pulmonary Fibrosis by SLC1A5-Dependent Glutamine Transport Blockade. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2023, 69, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, L.; Lv, H.; Liu, D.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, G.; Hu, Y. Targeting endometrial inflammation in intrauterine adhesion ameliorates endometrial fibrosis by priming MSCs to secrete C1INH. iScience 2023, 26, 107201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Ye, C.; Huang, Y.; Xu, B.; Wu, T.; Dong, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, L.; Hu, C.; Mao, J.; et al. Glutaminolysis regulates endometrial fibrosis in intrauterine adhesion via modulating mitochondrial function. Biol. Res. 2024, 57, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qazi, Y.; Wong, G.; Monson, B.; Stringham, J.; Ambati, B.K. Corneal transparency: Genesis, maintenance and dysfunction. Brain Res. Bull. 2010, 81, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Ogando, D.G.; Li, S.; Feng, M.; Price, F.W.; Tennessen, J.M.; Bonanno, J.A. Glutaminolysis is Essential for Energy Production and Ion Transport in Human Corneal Endothelium. EBioMedicine 2017, 16, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, J.A.; Shyam, R.; Choi, M.; Ogando, D.G. The H+ Transporter SLC4A11: Roles in Metabolism, Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Uncoupling. Cells 2022, 11, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chng, Z.; Peh, G.S.L.; Herath, W.B.; Cheng, T.Y.D.; Ang, H.-P.; Toh, K.-P.; Robson, P.; Mehta, J.S.; Colman, A. High Throughput Gene Expression Analysis Identifies Reliable Expression Markers of Human Corneal Endothelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, D.; Loganathan, S.K.; Chiu, A.M.; Lukowski, C.M.; Casey, J.R. Human Corneal Expression of SLC4A11, a Gene Mutated in Endothelial Corneal Dystrophies. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, L.; Li, T.; Liu, Y. High SLC4A11 expression is an independent predictor for poor overall survival in grade 3/4 serous ovarian cancer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Peng, F.; Wu, L.; Zhuo, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Tian, L.; Jie, Y.; et al. Identification of glutamine as a potential therapeutic target in dry eye disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.K.-Y.; Lee, A.C.-K.; Chung, S.-Y.R.; Wong, M.-S.; Do, C.-W.; Lam, T.C.; Kong, H.-K. Upregulations of SNAT2 and GLS-1 Are Key Osmoregulatory Responses of Human Corneal Epithelial Cells to Hyperosmotic Stress. J. Proteome Res. 2025, 24, 2771–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yang, X.; Huang, J.; Shen, M.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Yuan, Y.; Dong, C.; Ma, X.; Yuan, F. Pharmacological Inhibition of Glutaminase 1 Attenuates Alkali-Induced Corneal Neovascularization by Modulating Macrophages. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Lorentzen, K.A.; Kistler, J.; Donaldson, P.J. Molecular identification and characterisation of the glycine transporter (GLYT1) and the glutamine/glutamate transporter (ASCT2) in the rat lens. Exp. Eye Res. 2006, 83, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.; Basta, M.; Seifert, E. A role for mitochondrial remodeling in lens fibrotic disease. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 5115. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Li, L.; Luo, F.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, H. Uncovering the metabolic landscape of aqueous humor in posterior subcapsular cataract associated with hyperuricemia. Exp. Eye Res. 2025, 263, 110767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, E.; Dammeier, S.; Ajana, S.; Groenewoud, J.M.M.; Codrea, M.; Klose, F.; Lechanteur, Y.T.; Fauser, S.; Ueffing, M.; Delcourt, C.; et al. Metabolomics in serum of patients with non-advanced age-related macular degeneration reveals aberrations in the glutamine pathway. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, L.; Dong, C.; Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Dai, J.; Huang, J.; Yuan, F. MicroRNA-376b-3p Suppresses Choroidal Neovascularization by Regulating Glutaminolysis in Endothelial Cells. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Tran, V.; McCollum, L.; Bolok, Y.; Allan, K.; Yuan, A.; Hoppe, G.; Brunengraber, H.; Sears, J.E. Hyperoxia induces glutamine-fuelled anaplerosis in retinal Müller cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Yoo, T.-H. TGF-β Inhibitors for Therapeutic Management of Kidney Fibrosis. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massagué, J. TGFβ signalling in context. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.-M.; Nikolic-Paterson, D.J.; Lan, H.Y. TGF-β: The master regulator of fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, J.; Cui, H.; Xie, N.; Banerjee, S.; Guo, S.; Dubey, S.; Barnes, S.; Liu, G. Glutaminolysis Promotes Collagen Translation and Stability via α-Ketoglutarate–mediated mTOR Activation and Proline Hydroxylation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 58, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Yao, Y.; Gong, X.; Zhuo, Q.; Chen, J.; Tian, M.; Farzaneh, M. JMJD3: A critical epigenetic regulator in stem cell fate. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 19, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X. TET (Ten-eleven translocation) family proteins: Structure, biological functions and applications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmierer, B.; Hill, C.S. TGFβ–SMAD signal transduction: Molecular specificity and functional flexibility. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 970–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, R. Inhibition of glutamine metabolism: Acting on tumoral cells or on tumor microenvironment? Oncotarget 2023, 14, 755–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.E. Non-Smad pathways in TGF-β signaling. Cell Res. 2009, 19, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-K.; Park, K.-G. Targeting Glutamine Metabolism for Cancer Treatment. Biomol. Ther. 2018, 26, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, C.D. Why does chronic inflammation persist: An unexpected role for fibroblasts. Immunol. Lett. 2011, 138, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamanaka, R.B.; Mutlu, G.M. Metabolic requirements of pulmonary fibrosis: Role of fibroblast metabolism. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 6331–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Cao, Y.; Meng, G.; Qian, L.; Xu, T.; Yan, C.; Luo, O.; Wang, S.; Wei, J.; Ding, Y.; et al. Targeting glutaminase 1 attenuates stemness properties in hepatocellular carcinoma by increasing reactive oxygen species and suppressing Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. EBioMedicine 2019, 39, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usart, M.; Hansen, N.; Stetka, J.; Fonseca, T.A.; Guy, A.; Kimmerlin, Q.; Rai, S.; Hao-Shen, H.; Roux, J.; Dirnhofer, S.; et al. The glutaminase inhibitor CB-839 targets metabolic dependencies of JAK2-mutant hematopoiesis in MPN. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 2312–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.I.; Demo, S.D.; Dennison, J.B.; Chen, L.; Chernov-Rogan, T.; Goyal, B.; Janes, J.R.; Laidig, G.J.; Lewis, E.R.; Li, J.; et al. Antitumor Activity of the Glutaminase Inhibitor CB-839 in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Yuan, L.; Guo, H.; Li, W.; Pan, G.; Wang, C.; Li, D.; Liu, N. The Glutaminase Inhibitor Compound 968 Exhibits Potent In vitro and In vivo Anti-tumor Effects in Endometrial Cancer. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2023, 23, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotná, K.; Tenora, L.; Slusher, B.S.; Rais, R. Therapeutic resurgence of 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON) through tissue-targeted prodrugs. Adv. Pharmacol. 2024, 100, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.K.; Motz, K.M.; Ding, D.; Yin, L.; Duvvuri, M.; Feeley, M.; Hillel, A.T. Targeting metabolic abnormalities to reverse fibrosis in iatrogenic laryngotracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, E59–E67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, G.B.; Myers, W.P.L.; Reilly, H.C.; Putnam, R.C.; Magill, J.W.; Sykes, M.P.; Escher, G.C.; Karnofsky, D.A.; Burchenal, J.H. Pharmacological and initial therapeutic observations on 6-Diazo-5-Oxo-L-Norleucine (Don) in human neoplastic disease. Cancer 1957, 10, 1138–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katt, W.P.; Ramachandran, S.; Erickson, J.W.; Cerione, R.A. Dibenzophenanthridines as Inhibitors of Glutaminase C and Cancer Cell Proliferation. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2012, 11, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltzer, M.J.; Bennett, B.D.; Joshi, A.D.; Gao, P.; Thomas, A.G.; Ferraris, D.V.; Tsukamoto, T.; Rojas, C.J.; Slusher, B.S.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; et al. Inhibition of Glutaminase Preferentially Slows Growth of Glioma Cells with Mutant IDH1. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 8981–8987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Puviindran, V.; Nadesan, P.; Ding, X.; Shen, L.; Tang, Y.J.; Tsushima, H.; Yahara, Y.; I Ban, G.; Zhang, G.-F.; et al. Distinct Roles of Glutamine Metabolism in Benign and Malignant Cartilage Tumors with IDH Mutations. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2020, 37, 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Cui, H. Targeting Glutamine Induces Apoptosis: A Cancer Therapy Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 22830–22855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Geldermalsen, M.; Quek, L.-E.; Turner, N.; Freidman, N.; Pang, A.; Guan, Y.F.; Krycer, J.R.; Ryan, R.; Wang, Q.; Holst, J. Benzylserine inhibits breast cancer cell growth by disrupting intracellular amino acid homeostasis and triggering amino acid response pathways. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.; Voss, M.; Tawbi, H.; Gordon, M.; Tykodi, S.; Lam, E.; Vaishampayan, U.; Tannir, N.; Chaves, J.; Nikolinakos, P.; et al. A phase I/II study of the safety and efficacy of telaglenastat (CB-839) in combination with nivolumab in patients with metastatic melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, and non-small-cell lung cancer. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanaford, A.R.; Alt, J.; Rais, R.; Wang, S.Z.; Kaur, H.; Thorek, D.L.; Eberhart, C.G.; Slusher, B.S.; Martin, A.M.; Raabe, E.H. Orally bioavailable glutamine antagonist prodrug JHU-083 penetrates mouse brain and suppresses the growth of MYC-driven medulloblastoma. Transl. Oncol. 2019, 12, 1314–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, A.S.; Rosa, M.d.C.; Stumpo, V.; Rais, R.; Slusher, B.S.; Riggins, G.J. The glutamine antagonist prodrug JHU-083 slows malignant glioma growth and disrupts mTOR signaling. Neurooncol. Adv. 2021, 3, vdaa149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Shaw, A.T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Reis, L.M.; Adamoski, D.; Souza, R.O.O.; Ascenção, C.F.R.; de Oliveira, K.R.S.; Corrêa-Da-Silva, F.; Patroni, F.M.d.S.; Dias, M.M.; Consonni, S.R.; de Moraes-Vieira, P.M.M.; et al. Dual inhibition of glutaminase and carnitine palmitoyltransferase decreases growth and migration of glutaminase inhibition–resistant triple-negative breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 9342–9357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Xie, N.; Jiang, D.; Banerjee, S.; Ge, J.; Sanders, Y.Y.; Liu, G. Inhibition of Glutaminase 1 Attenuates Experimental Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 61, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Ruiz-Rodado, V.; Dowdy, T.; Huang, S.; Issaq, S.H.; Beck, J.; Wang, H.; Hoang, C.T.; Lita, A.; Larion, M.; et al. Glutaminase-1 (GLS1) inhibition limits metastatic progression in osteosarcoma. Cancer Metab. 2020, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Mahony, C.B.; Torres, A.; Murillo-Saich, J.; Kemble, S.; Cedeno, M.; John, P.; Bhatti, A.; Croft, A.P.; Guma, M. Dual inhibition of glycolysis and glutaminolysis for synergistic therapy of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2023, 25, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Byun, J.K.; Choi, Y.K.; Park, K.G. Targeting glutamine metabolism as a therapeutic strategy for cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumoy, L.; Genbauffe, A.; Sant’Angelo, D.; Everaert, M.; Mukeba-Harchies, L.; Sarry, J.-E.; Declèves, A.-E.; Journe, F. Therapeutic Potential of Glutaminase Inhibition Targeting Metabolic Adaptations in Resistant Melanomas to Targeted Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Toki, H.; Furuya, A.; Ando, H. Establishment of monoclonal antibodies against cell surface domains of ASCT2/SLC1A5 and their inhibition of glutamine-dependent tumor cell growth. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 482, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahavi, D.; Weiner, L. Monoclonal Antibodies in Cancer Therapy. Antibodies 2020, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemberg, K.M.; Vornov, J.J.; Rais, R.; Slusher, B.S. We’re Not “DON” Yet: Optimal Dosing and Prodrug Delivery of 6-Diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 1824–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.-D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wei, Y.-C.; Han, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.-R.; Li, Z.-Z.; Jiang, J.-W.; et al. A Novel ASCT2 Inhibitor, C118P, Blocks Glutamine Transport and Exhibits Antitumour Efficacy in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, R.D.; Zhao, L.; Englert, J.M.; Sun, I.M.; Oh, M.H.; Sun, I.H.; Arwood, M.L.; Bettencourt, I.A.; Patel, C.H.; Wen, J.; et al. Glutamine blockade induces divergent metabolic programs to overcome tumor immune evasion. Science 2019, 366, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzer, J.; Bach, N.C.; Forler, D.; Sieber, S.A. Target discovery of acivicin in cancer cells elucidates its mechanism of growth inhibition. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olver, I.; Green, M.; Millward, M.; Bishop, J. Phase II study of acivicin in patients with recurrent high grade astrocytoma. J. Clin. Neurosci. 1998, 5, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.D.; E Sant, M.; Christopherson, R.I. Cytotoxic mechanisms of glutamine antagonists in mouse L1210 leukemia. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 11377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, I.; Yoshino, H.; Fukumoto, W.; Tamai, M.; Okamura, S.; Osako, Y.; Sakaguchi, T.; Inoguchi, S.; Matsushita, R.; Yamada, Y.; et al. Targeting of the glutamine transporter SLC1A5 induces cellular senescence in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 611, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esslinger, C.S.; Cybulski, K.A.; Rhoderick, J.F. Nγ-Aryl glutamine analogues as probes of the ASCT2 neutral amino acid transporter binding site. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.; Sabino, C.; Taurino, G.; Bianchi, M.G.; Andreoli, R.; Giuliani, N.; Bussolati, O. GPNA inhibits the sodium-independent transport system l for neutral amino acids. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalota, A.; Skwarska, A.; Verma, D.; Pradhan, K.; Chaudhry, S.; Poigaialwar, G.; Shukla, V.; Yuan, Y.; Wagenblast, E.; Zhou, D.; et al. Targeting SLC38A1 non-conventional glutamine transporter in high risk MDS/AML. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-T.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.-C.; Liu, Q.-L. METTL3-mediated m6A methylation of SLC38A1 stimulates cervical cancer growth. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 716, 150039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.E.Z.; Lu, X.; Talebi, Z.; Jeon, J.Y.; Buelow, D.R.; Gibson, A.A.; Uddin, M.E.; Brinton, L.T.; Nguyen, J.; Collins, M.; et al. Gilteritinib Inhibits Glutamine Uptake and Utilization in FLT3-ITD–Positive AML. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koe, J.C.; Zhong, Y.C.; Pashaoskooie, K.; Kaczorowski, G.J.; Garcia, M.L.; Parker, S.J. Metabolomics analysis of SNAT2-deficient cells: Implications for the discovery of selective small-molecule inhibitors of an amino acid transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 110525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier-Coles, G.; Bröer, A.; McLeod, M.D.; George, A.J.; Hannan, R.D.; Bröer, S. Identification and characterization of a novel SNAT2 (SLC38A2) inhibitor reveals synergy with glucose transport inhibition in cancer cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 963066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, K.; Yu, S.; Hao, C.; Ma, Z.; Fu, X.; Qin, M.Q.; Xu, Z.; Fan, L. Blockade of the amino acid transporter SLC6A14 suppresses tumor growth in colorectal Cancer. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Bao, J.; Lei, Z.; Ma, M.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Q.; Xu, B.; Hu, T.; et al. α-Methyl-Tryptophan Inhibits SLC6A14 Expression and Exhibits Immunomodulatory Effects in Crohn’s Disease. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 1127–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coothankandaswamy, V.; Cao, S.; Xu, Y.; Prasad, P.D.; Singh, P.K.; Reynolds, C.P.; Yang, S.; Ogura, J.; Ganapathy, V.; Bhutia, Y.D. Amino acid transporter SLC6A14 is a novel and effective drug target for pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 3292–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, S.; Pan, C.Q.; Zimmermann, S.C.; Duvall, B.; Tsukamoto, T.; Low, B.C.; Sivaraman, J. Structural basis for exploring the allosteric inhibition of human kidney type glutaminase. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 57943–57954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, S.C.; Wolf, E.F.; Luu, A.; Thomas, A.G.; Stathis, M.; Poore, B.; Nguyen, C.; Le, A.; Rojas, C.; Slusher, B.S.; et al. Allosteric Glutaminase Inhibitors Based on a 1,4-Di(5-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)butane Scaffold. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momcilovic, M.; Bailey, S.T.; Lee, J.T.; Fishbein, M.C.; Magyar, C.; Braas, D.; Graeber, T.; Jackson, N.J.; Czernin, J.; Emberley, E.; et al. Targeted Inhibition of EGFR and Glutaminase Induces Metabolic Crisis in EGFR Mutant Lung Cancer. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczka, A.M.; Reynolds, P.A. Glutaminase inhibition in renal cell carcinoma therapy. Cancer Drug Resist. 2019, 2, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.M.; Dytfeld, D.; Reyes, L.; Robinson, R.M.; Smith, B.; Manevich, Y.; Jakubowiak, A.; Komarnicki, M.; Przybylowicz-Chalecka, A.; Szczepaniak, T.; et al. Glutaminase inhibitor CB-839 synergizes with carfilzomib in resistant multiple myeloma cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 35863–35876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukey, M.J.; Cluntun, A.A.; Katt, W.P.; Lin, M.-C.J.; Druso, J.E.; Ramachandran, S.; Erickson, J.W.; Le, H.H.; Wang, Z.-E.; Blank, B.; et al. Liver-Type Glutaminase GLS2 Is a Druggable Metabolic Node in Luminal-Subtype Breast Cancer. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 76–88.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherratt, M.J. Age-Related Tissue Stiffening: Cause and Effect. Adv. Wound Care 2013, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Kilpatrick, J.I.; Lukasz, B.; Jarvis, S.P.; McDonnell, F.; Wallace, D.M.; Clark, A.F.; O’Brien, C.J. Increased Substrate Stiffness Elicits a Myofibroblastic Phenotype in Human Lamina Cribrosa Cells. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.O.; Beiser, J.A.; Brandt, J.D.; Heuer, D.K.; Higginbotham, E.J.; Johnson, C.A.; Keltner, J.L.; Miller, J.P.; Parrish, R.K.; Wilson, M.R.; et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: Baseline Factors That Predict the Onset of Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2002, 120, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, M.; Pacciani, R.G.; Lee, R.K.; Battacharya, S.K. Aqueous Humor Dynamics: A Review. Open Ophthalmol. J. 2010, 4, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fautsch, M.P.; Johnson, D.H. Aqueous Humor Outflow: What Do We Know? Where Will It Lead Us? Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costagliola, C.; dell’Omo, R.; Agnifili, L.; Bartollino, S.; Fea, A.M.; Uva, M.G.; Zeppa, L.; Mastropasqua, L. How many aqueous humor outflow pathways are there? Surv. Ophthalmol. 2020, 65, 144–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranka, J.A.; Kelley, M.J.; Acott, T.S.; Keller, K.E. Extracellular matrix in the trabecular meshwork: Intraocular pressure regulation and dysregulation in glaucoma. Exp. Eye Res. 2015, 133, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.M.; Murphy-Ullrich, J.E.; Downs, J.C.; O’Brien, C.J. The role of matricellular proteins in glaucoma. Matrix Biol. 2014, 37, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.J.; Wiggs, J.L. Glaucoma: Genes, phenotypes, and new directions for therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 3064–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Last, J.A.; Pan, T.; Ding, Y.; Reilly, C.M.; Keller, K.; Acott, T.S.; Fautsch, M.P.; Murphy, C.J.; Russell, P. Elastic Modulus Determination of Normal and Glaucomatous Human Trabecular Meshwork. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.-F.; Holden, P.; Sun, Y.Y.; Faralli, J.A.; Peters, D.M.; Keller, K.E. Fibrosis-Related Gene and Protein Expression in Normal and Glaucomatous Trabecular Meshwork Cells. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, B.; Lester, K.; Lane, B.; Fan, X.; Goljanek-Whysall, K.; Simpson, D.A.; Sheridan, C.; Willoughby, C.E. Genome-wide transcriptome profiling of human trabecular meshwork cells treated with TGF-β2. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faralli, J.A.; Filla, M.S.; Peters, D.M. Role of integrins in the development of fibrosis in the trabecular meshwork. Front. Ophthalmol. 2023, 3, 1274797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamm, E.R.; Fuchshofer, R. What Increases Outflow Resistance in Primary Open-angle Glaucoma? Surv. Ophthalmol. 2007, 52, S101–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagen, D.; Faralli, J.A.; Filla, M.S.; Peters, D.M. The Role of Integrins in the Trabecular Meshwork. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 30, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, R.A.; Perkumas, K.M.; Campbell, M.; Farrar, G.J.; Stamer, W.D.; Humphries, P.; O’Callaghan, J.; O’Brien, C.J. Fibrotic Changes to Schlemm’s Canal Endothelial Cells in Glaucoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overby, D.R.; Zhou, E.H.; Vargas-Pinto, R.; Pedrigi, R.M.; Fuchshofer, R.; Braakman, S.T.; Gupta, R.; Perkumas, K.M.; Sherwood, J.M.; Vahabikashi, A.; et al. Altered mechanobiology of Schlemm’s canal endothelial cells in glaucoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13876–13881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirwan, R.P.; Wordinger, R.J.; Clark, A.F.; O’Brien, C.J. Differential global and extra-cellular matrix focused gene expression patterns between normal and glaucomatous human lamina cribrosa cells. Mol. Vis. 2009, 15, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, M.R.; Ye, H. Glaucoma: Changes in Extracellular Matrix in the Optic Nerve Head. Ann. Med. 1993, 25, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, J.S.; O’Brien, C.; Stamer, W.D. Life under pressure: The role of ocular cribriform cells in preventing glaucoma. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 151, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbiani, G.; Ryan, G.B.; Majno, G. Presence of modified fibroblasts in granulation tissue and their possible role in wound contraction. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1971, 27, 549–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, R.P.; Felice, L.; Clark, A.F.; O’Brien, C.J.; Leonard, M.O. Hypoxia Regulated Gene Transcription in Human Optic Nerve Lamina Cribrosa Cells in Culture. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 2243–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.; Irnaten, M.; Hopkins, A.; O’Callaghan, J.; Stamer, W.D.; Clark, A.F.; Wallace, D.; O’Brien, C.J. Matrix Mechanotransduction via Yes-Associated Protein in Human Lamina Cribrosa Cells in Glaucoma. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, R.P.; Leonard, M.O.; Murphy, M.; Clark, A.F.; O’Brien, C.J. Transforming growth factor-β-regulated gene transcription and protein expression in human GFAP-negative lamina cribrosa cells. Glia 2005, 52, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElnea, E.; Quill, B.; Docherty, N.; Irnaten, M.; Siah, W.; Clark, A.; O’Brien, C.; Wallace, D. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and calcium overload in human lamina cribrosa cells from glaucoma donors. Mol. Vis. 2011, 17, 1182. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, K.; O’Brien, C.J.; Zhdanov, A.V.; Papkovsky, D.B.; Clark, A.F.; Stamer, W.D.; Irnaten, M. Reduced Oxidative Phosphorylation and Increased Glycolysis in Human Glaucoma Lamina Cribrosa Cells. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 4, Erratum in: Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeimer, R.C.; Ogura, Y. The Relation Between Glaucomatous Damage and Optic Nerve Head Mechanical Compliance. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1989, 107, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, R.C.; Li, J.; Chan, W.A.; Tripathi, B.J. Aqueous Humor in Glaucomatous Eyes Contains an Increased Level of TGF-β2. Exp. Eye Res. 1994, 59, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, S.H.; Lee, T.-I.; Chung, Y.S.; Kim, H.K. Transforming Growth Factor-β Levels in Human Aqueous Humor of Glaucomatous, Diabetic and Uveitic Eyes. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 20, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, J.D.; Taylor, A.W.; Ricard, C.S.; Vidal, I.; Hernandez, M.R. Transforming growth factor beta isoforms in human optic nerve heads. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 83, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhavoronkov, A.; Izumchenko, E.; Kanherkar, R.R.; Teka, M.; Cantor, C.; Manaye, K.; Sidransky, D.; West, M.D.; Makarev, E.; Csoka, A.B. Pro-fibrotic pathway activation in trabecular meshwork and lamina cribrosa is the main driving force of glaucoma. Cell Cycle 2016, 15, 1643–1652, Erratum in: Cell Cycle 2016, 15, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, K.E.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Borrás, T.; Brunner, T.M.; Chansangpetch, S.; Clark, A.F.; Dismuke, W.M.; Du, Y.; Elliott, M.H.; Ethier, C.R.; et al. Consensus recommendations for trabecular meshwork cell isolation, characterization and culture. Exp. Eye Res. 2018, 171, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buisset, A.; Gohier, P.; Leruez, S.; Muller, J.; Amati-Bonneau, P.; Lenaers, G.; Bonneau, D.; Simard, G.; Procaccio, V.; Annweiler, C.; et al. Metabolomic Profiling of Aqueous Humor in Glaucoma Points to Taurine and Spermine Deficiency: Findings from the Eye-D Study. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillo, A.; Marin, S.; Serrano-Marín, J.; Binetti, N.; Navarro, G.; Cascante, M.; Sánchez-Navés, J.; Franco, R. Targeted Metabolomics Shows That the Level of Glutamine, Kynurenine, Acyl-Carnitines and Lysophosphatidylcholines Is Significantly Increased in the Aqueous Humor of Glaucoma Patients. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 935084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breda, J.B.; Sava, A.C.; Himmelreich, U.; Somers, A.; Matthys, C.; Sousa, A.R.; Vandewalle, E.; Stalmans, I. Metabolomic profiling of aqueous humor from glaucoma patients-The metabolomics in surgical ophthalmological patients (MISO) study. Exp. Eye Res. 2020, 201, 108268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeleznik, O.A.; Kang, J.H.; Lasky-Su, J.; Eliassen, A.H.; Frueh, L.; Clish, C.B.; Rosner, B.A.; Elze, T.; Hysi, P.; Khawaja, A.; et al. Plasma metabolite profile for primary open-angle glaucoma in three US cohorts and the UK Biobank. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, X.-W.; Liang, G.; Pan, C.-W. Metabolomics in Glaucoma: A Systematic Review. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsukasa, M.; Sotozono, C.; Shimbo, K.; Ono, N.; Miyano, H.; Okano, A.; Hamuro, J.; Kinoshita, S. Amino Acid Profiles in Human Tear Fluids Analyzed by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2011, 151, 799–808.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Yücel, Y.H. Glaucoma as a neurodegenerative disease. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2007, 18, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.; Saxena, R.; Tripathi, M.; Vibha, D.; Dhiman, R. Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and glaucoma: Overlaps and missing links. Eye 2020, 34, 1546–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inman, D.M.; Harun-Or-Rashid, M. Metabolic Vulnerability in the Neurodegenerative Disease Glaucoma. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-A.; Chen, C.-L.; Huang, Y.-H.; Evans, E.E.; Cheng, C.-C.; Chuang, Y.-J.; Zhang, C.; Le, A. Inhibition of glutaminolysis in combination with other therapies to improve cancer treatment. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021, 62, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, B. The Role and Mechanism of Nicotinamide Riboside in Oxidative Damage and a Fibrosis Model of Trabecular Meshwork Cells. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasetti, R.B.; Patel, P.D.; Maddineni, P.; Patil, S.; Kiehlbauch, C.; Millar, J.C.; Searby, C.C.; Raghunathan, V.; Sheffield, V.C.; Zode, G.S. ATF4 leads to glaucoma by promoting protein synthesis and ER client protein load. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, F.; Liu, P.; Huang, H.; Feng, X.; Li, L.; Sun, Y.; Kaufman, R.J.; Hu, Y. RGC-specific ATF4 and/or CHOP deletion rescues glaucomatous neurodegeneration and visual function. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2023, 33, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Tolman, N.; Segrè, A.V.; Stuart, K.V.; Zeleznik, O.A.; Vallabh, N.A.; Hu, K.; Zebardast, N.; Hanyuda, A.; Raita, Y.; et al. Pyruvate and related energetic metabolites modulate resilience against high genetic risk for glaucoma. eLife 2025, 14, RP105576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kelly, Á.; Irnaten, M.; O’Brien, C. Targeting the Glutaminolysis Pathway in Glaucoma-Associated Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010012

Kelly Á, Irnaten M, O’Brien C. Targeting the Glutaminolysis Pathway in Glaucoma-Associated Fibrosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleKelly, Áine, Mustapha Irnaten, and Colm O’Brien. 2026. "Targeting the Glutaminolysis Pathway in Glaucoma-Associated Fibrosis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010012

APA StyleKelly, Á., Irnaten, M., & O’Brien, C. (2026). Targeting the Glutaminolysis Pathway in Glaucoma-Associated Fibrosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010012