Phylogenomic Reconstruction and Functional Divergence of the PARP Gene Family Illuminate Its Role in Plant Terrestrialization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of the PARP Gene Family

2.2. Expansion of the PARP Gene Family During Plant Terrestrialization

2.3. Subfamily Specific Conserved Motifs and Gene Structures

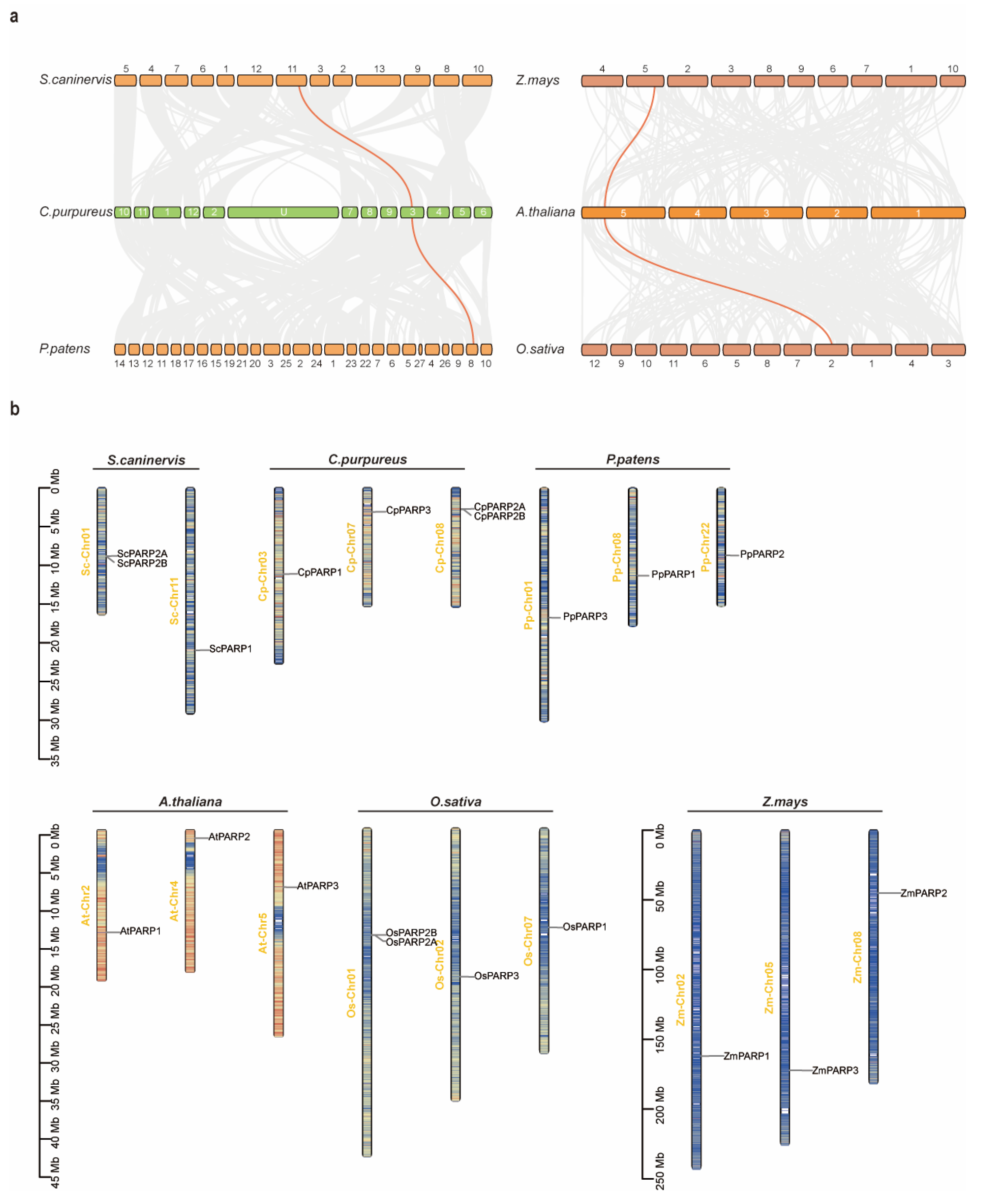

2.4. Synteny Analysis Reveals Divergent Evolutionary Fates of PARP Subfamilies

2.5. Sequence Divergence and Conservation Among PARP Subfamilies

2.6. Evolutionary Diversification of Regulatory Elements in PARP Promoters

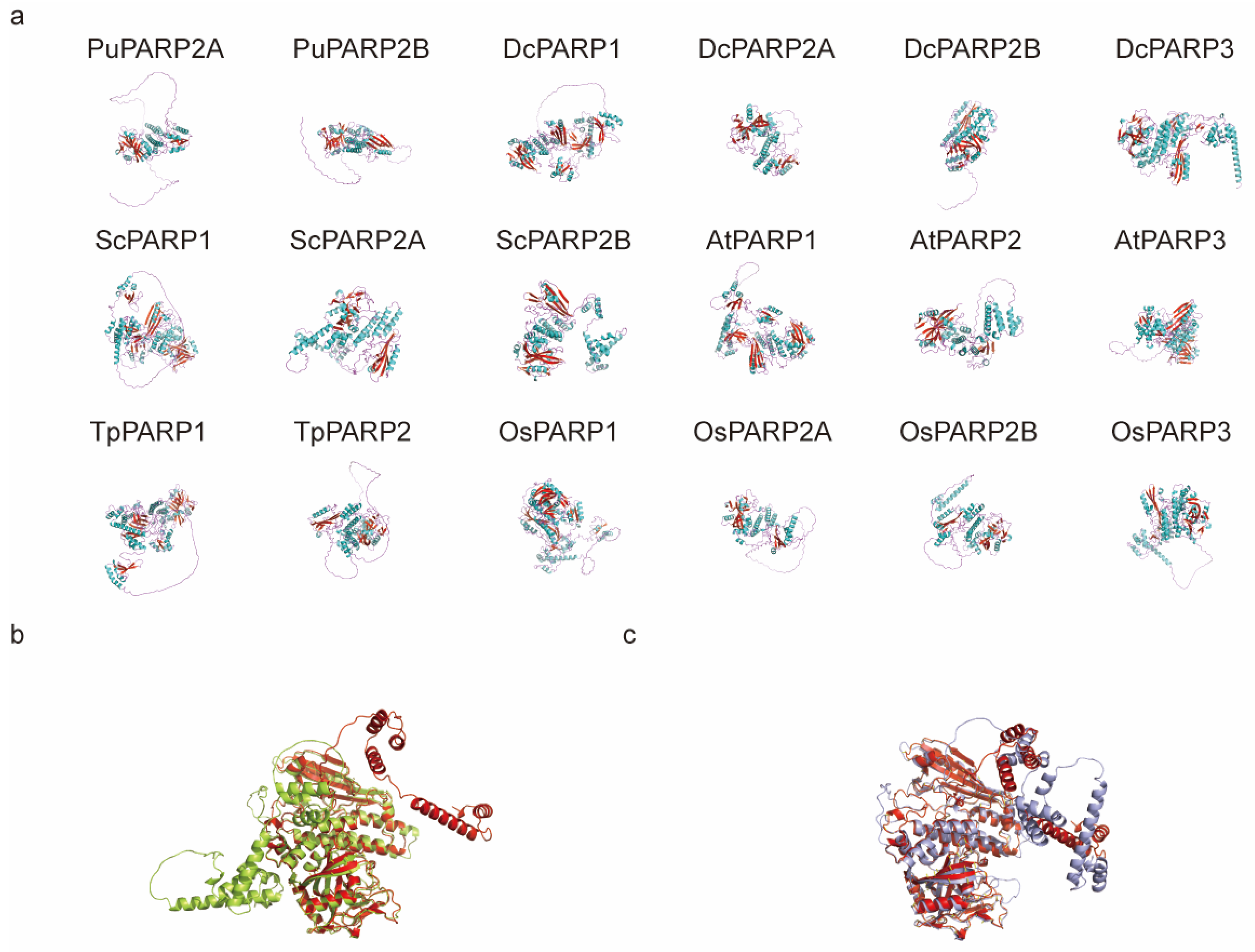

2.7. Predicted 3D Structures Reveal Subfamily Specific Conformations and Divergence in Tandem Duplicates

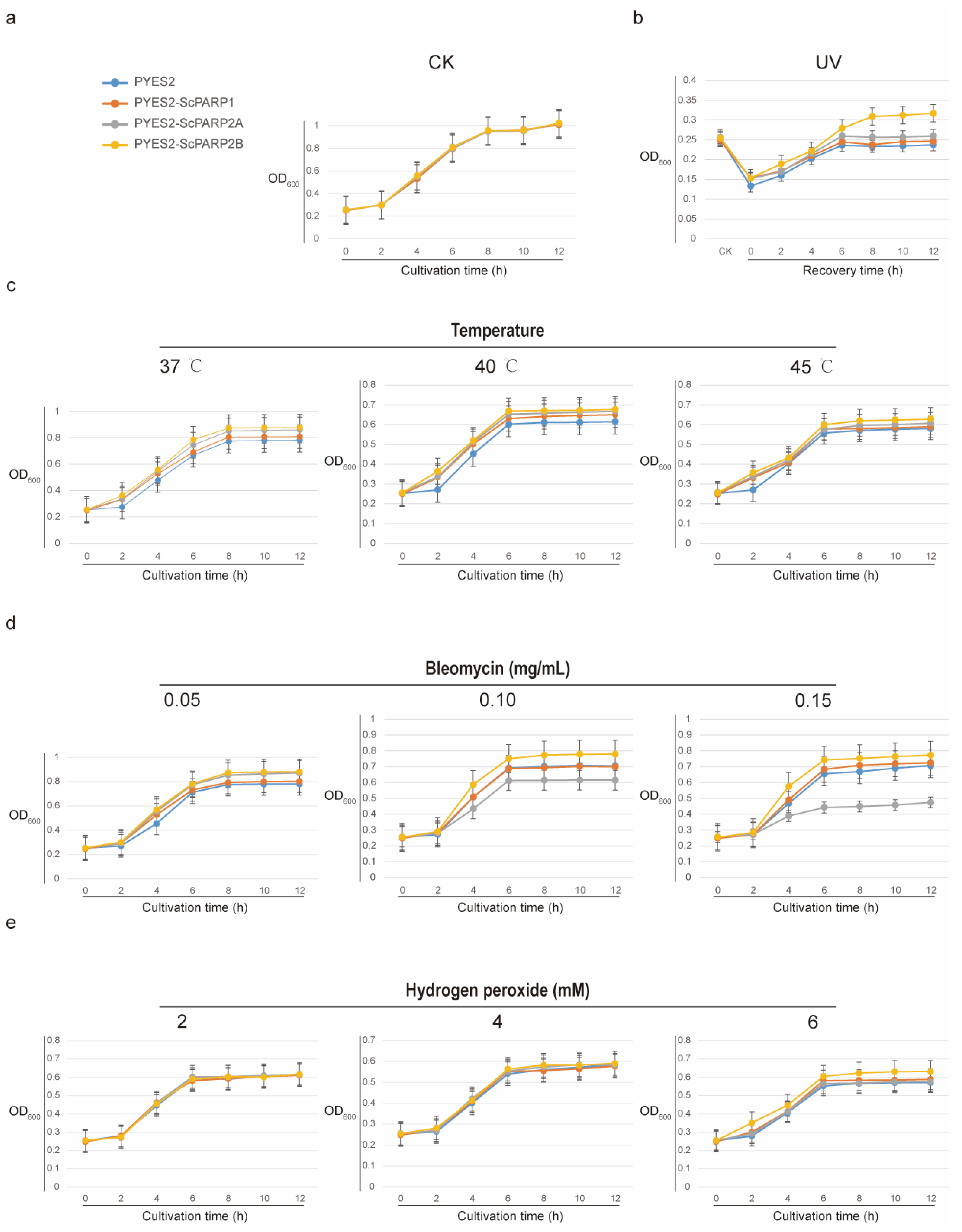

2.8. S. caninervis PARP Proteins Confer Multi-Stress Tolerance in Yeast

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification Statistics and Physicochemical Property Predictions for Members of the Multispecies PARP Gene Family

4.2. Phylogenetic Tree Construction and Conserved Motifs

4.3. Chromosome Distribution and Colinearity Analysis

4.4. Cis-Element Analysis

4.5. Three-Dimensional Structure Prediction and Comparison

4.6. Preliminary Functional Characterization of the ScPARP Gene in a Yeast System

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hegedűs, C.; Virág, L. Inputs and outputs of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation: Relevance to oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray Chaudhuri, A.; Nussenzweig, A. The multifaceted roles of PARP1 in DNA repair and chromatin remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtin, N.J.; Szabo, C. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition: Past, present and future. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 711–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simbulan-Rosenthal, C.M.; Rosenthal, D.S.; Smulson, M.E. Purification and characterization of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated DNA replication/repair complexes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 780, 165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, A.W.; Amé, J.-C.; Roe, S.M.; Good, V.; De Murcia, G.; Pearl, L.H. Crystal structure of the catalytic fragment of murine poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Tang, Y.-D.; Zhan, G.; Su, C.; Zheng, C. The Critical Role of PARPs in Regulating Innate Immune Responses. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 712556, Erratum in: Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1253094.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlberg, E.; Karlberg, T.; Kouznetsova, E.; Markova, N.; Macchiarulo, A.; Thorsell, A.-G.; Pol, E.; Frostell, Å.; Ekblad, T.; Öncü, D.; et al. Family-wide chemical profiling and structural analysis of PARP and tankyrase inhibitors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, H.; Reche, P.A.; Bazan, F.; Dittmar, K.; Haag, F.; Koch-Nolte, F. In silico characterization of the family of PARP-like poly(ADP-ribosyl)transferases (pARTs). BMC Genom. 2005, 6, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sun, B.; Zhao, C. Poly (ADP-Ribose) polymerase 1 and parthanatos in neurological diseases: From pathogenesis to therapeutic opportunities. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 187, 106314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Keppler, B.D.; Wise, R.R.; Bent, A.F. PARP2 Is the Predominant Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase in Arabidopsis DNA Damage and Immune Responses. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouleau, M.; Patel, A.; Hendzel, M.J.; Kaufmann, S.H.; Poirier, G.G. PARP inhibition: PARP1 and beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissel, D.; Peiter, E. Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerases in Plants and Their Human Counterparts: Parallels and Peculiarities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, M.S.; Lindahl, T. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) formation in DNA repair. Nature 1992, 356, 356–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldecott, K.W.; McKeown, C.K.; Tucker, J.D.; Ljungquist, S.; Thompson, L.H. An interaction between the mammalian DNA repair protein XRCC1 and DNA ligase III. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 14, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dantzer, F.; de la Rubia, G.; Ménissier-de Murcia, J.; Hostomsky, Z.; de Murcia, G.; Schreiber, V. Base excision repair is impaired in mammalian cells lacking Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 7559–7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochegger, H.; Dejsuphong, D.; Fukushima, T.; Morrison, C.; Sonoda, E.; Schreiber, V.; Zhao, G.Y.; Saberi, A.; Masutani, M.; Adachi, N.; et al. Parp-1 protects homologous recombination from interference by Ku and Ligase IV in vertebrate cells. Embo J. 2006, 25, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.J.; Thakar, T.; Nicolae, C.M.; Moldovan, G.-L. PARP14 regulates cyclin D1 expression to promote cell-cycle progression. Oncogene 2021, 40, 4872–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva Dvořák, T.; Prochazkova, K.; Yang, F.; Jemelkova, J.; Finke, A.; Dorn, A.; Said, M.; Puchta, H.; Pecinka, A. SMC5/6 complex-mediated SUMOylation stimulates DNA–protein cross-link repair in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 1532–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadhan, V.; Manikandan, M.S.; Nagarajan, A.; Palaniyandi, T.; Ravi, M.; Sankareswaran, S.K.; Baskar, G.; Wahab, M.R.A.; Surendran, H. Ataxia-Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM) gene signaling pathways in human cancers and their therapeutic implications. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2024, 260, 155447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipakova, S.; Kuanbay, A.; Saint-Pierre, C.; Gasparutto, D.; Baiken, Y.; Groisman, R.; Ishchenko, A.A.; Saparbaev, M.; Bissenbaev, A.K. The Arabidopsis thaliana Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerases 1 and 2 Modify DNA by ADP-Ribosylating Terminal Phosphate Residues. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 606596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainonen, J.P.; Shapiguzov, A.; Vaattovaara, A.; Kangasjärvi, J. Plant PARPs, PARGs and PARP-like Proteins. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2016, 17, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arena, C.; Mistretta, C.; Di Natale, E.; Mennella, M.R.F.; De Santo, A.V.; De Maio, A. Characterization and role of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in the Mediterranean species Cistus incanus L. under different temperature conditions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 49, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arena, C.; De Micco, V.; De Maio, A. Growth alteration and leaf biochemical responses in Phaseolus vulgaris exposed to different doses of ionising radiation. Plant Biol. 2014, 16, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorio, P.; Guida, G.; Mistretta, C.; Sellami, M.H.; Oliva, M.; Punzo, P.; Iovieno, P.; Arena, C.; De Maio, A.; Grillo, S.; et al. Physiological, biochemical and molecular responses to water stress and rehydration in Mediterranean adapted tomato landraces. Plant Biol. 2018, 20, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Liu, C.; Shan, L.; He, P. Protein ADP-Ribosylation Takes Control in Plant-Bacterium Interactions. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet-Chabeaud, G.; Godon, C.; Brutesco, C.; de Murcia, G.; Kazmaier, M. Ionising radiation induces the expression of PARP-1 and PARP-2 genes in Arabidopsis. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2001, 265, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Pan, W.; Chen, W.; Lian, Q.; Wu, Q.; Lv, Z.; Cheng, X.; Ge, X. New perspectives on the plant PARP family: Arabidopsis PARP3 is inactive, and PARP1 exhibits predominant poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase activity in response to DNA damage. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Song, S.; Liu, J. Poly ADP-ribose polymerase-1 promotes seed-setting rate by facilitating gametophyte development and meiosis in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant J. 2021, 107, 760–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiychuk, E.; Cottrill, P.B.; Storozhenko, S.; Fuangthong, M.; Chen, Y.; O’farrell, M.K.; Van Montagu, M.; Inzé, D.; Kushnir, S. Higher plants possess two structurally different poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases. Plant J. 1998, 15, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Shall, S.; O’Farrell, M. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in plant nuclei. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994, 224, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Zhang, G.Y.; Yan, C.H.; Dai, Y.R. Involvement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and activation of caspase-3-like protease in heat shock-induced apoptosis in tobacco suspension cells. FEBS Lett. 2000, 474, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyagi Blue, Y.; Kusumi, J.; Satake, A. Copy number analyses of DNA repair genes reveal the role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) in tree longevity. iScience 2021, 24, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbst, J.; Li, Q.-Q.; De Veylder, L. Mechanistic insights into DNA damage recognition and checkpoint control in plants. Nat. Plants 2024, 10, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rissel, D.; Heym, P.P.; Thor, K.; Brandt, W.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Peiter, E. No Silver Bullet—Canonical Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerases (PARPs) Are No Universal Factors of Abiotic and Biotic Stress Resistance of Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.; Li, L.; Fattah, F.J.; Dong, Y.; Bey, E.A.; Patel, M.; Gao, J.; Boothman, D.A. Review of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) mechanisms of action and rationale for targeting in cancer and other diseases. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2014, 24, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, R.M.; Crane, P.R.; DiMichele, W.A.; Kenrick, P.R.; Rowe, N.P.; Speck, T.; Stein, W.E. EARLY EVOLUTION OF LAND PLANTS: Phylogeny, Physiology, and Ecology of the Primary Terrestrial Radiation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1998, 29, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, J.L. Walkabout on the long branches of plant evolution. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013, 16, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackenberg, D.; Sakayama, H.; Nishiyama, T.; Pandey, S. Characterization of the heterotrimeric G-protein complex and its regulator from the green alga Chara braunii expands the evolutionary breadth of plant G-protein signaling. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 1510–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.-W.; Melkonian, M.; Rothfels, C.J.; Villarreal, J.C.; Stevenson, D.W.; Graham, S.W.; Wong, G.K.-S.; Pryer, K.M.; Mathews, S. Phytochrome diversity in green plants and the origin of canonical plant phytochromes. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lespinet, O.; Wolf, Y.I.; Koonin, E.V.; Aravind, L. The role of lineage-specific gene family expansion in the evolution of eukaryotes. Genome Res. 2002, 12, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesenko, I.A.; Arapidi, G.P.; Skripnikov, A.Y.; Alexeev, D.G.; Kostryukova, E.S.; Manolov, A.I.; Altukhov, I.A.; Khazigaleeva, R.A.; Seredina, A.V.; Kovalchuk, S.I.; et al. Specific pools of endogenous peptides are present in gametophore, protonema, and protoplast cells of the moss Physcomitrella patens. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, E.R. Molecular adaptation and the origin of land plants. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2003, 29, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rensing, S.A.; Lang, D.; Zimmer, A.D.; Terry, A.; Salamov, A.; Shapiro, H.; Nishiyama, T.; Perroud, P.-F.; Lindquist, E.A.; Kamisugi, Y.; et al. The Physcomitrella genome reveals evolutionary insights into the conquest of land by plants. Science 2008, 319, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zou, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Ju, Y.; Zeng, X. Review of Protein Subcellular Localization Prediction. Curr. Bioinform. 2014, 9, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amé, J.C.; Spenlehauer, C.; de Murcia, G. The PARP superfamily. Bioessays 2004, 26, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S.; Chesarone-Cataldo, M.; Todorova, T.; Huang, Y.-H.; Chang, P. A systematic analysis of the PARP protein family identifies new functions critical for cell physiology. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szántó, M.; Gupte, R.; Kraus, W.L.; Pacher, P.; Bai, P. PARPs in lipid metabolism and related diseases. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 84, 101117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langelier, M.F.; Planck, J.L.; Roy, S.; Pascal, J.M. Structural basis for DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by human PARP-1. Science 2012, 336, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravind, L.; Koonin, E.V. SAP—A putative DNA-binding motif involved in chromosomal organization. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, A.J.; Quatrano, R.S. Between a rock and a dry place: The water-stressed moss. Mol. Plant 2009, 2, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, J.; Archibald, J.M. Plant evolution: Landmarks on the path to terrestrial life. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrant, J.M.; Moore, J.P. Programming desiccation-tolerance: From plants to seeds to resurrection plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Godzik, A. Cd-hit: A fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1658–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Niu, B.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, S.; Li, W. CD-HIT: Accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 3150–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, B.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Oliver, M.J.; Zhang, D. Telomere-to-telomere genome of the desiccation-tolerant desert moss Syntrichia caninervis illuminates Copia-dominant centromeric architecture. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 927–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, T.; Sakayama, H.; de Vries, J.; Buschmann, H.; Saint-Marcoux, D.; Ullrich, K.K.; Haas, F.B.; Vanderstraeten, L.; Becker, D.; Lang, D.; et al. The Chara Genome: Secondary Complexity and Implications for Plant Terrestrialization. Cell 2018, 174, 448–464.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.C.; Luciani, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Park, Y.; López, R.; Finn, R.D. HMMER web server: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W200–W204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Bateman, A.; Clements, J.; Coggill, P.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Eddy, S.R.; Heger, A.; Hetherington, K.; Holm, L.; Mistry, J.; et al. Pfam: The protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D222–D230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534, Erratum in: Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 2461.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procter, J.B.; Carstairs, G.M.; Soares, B.; Mourao, K.; Ofoegbu, T.C.; Barton, D.; Lui, L.; Menard, A.; Sherstnev, N.; Roldan-Martinez, D.; et al. Alignment of Biological Sequences with Jalview. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2231, 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ginestet, C. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2011, 174, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLano, W.L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. 2002. Available online: http://www.pymol.org/ (accessed on 19 August 2025).

| Gene Model ID | Species | Class | CDS Length (bp) | Peptide Residue (AA) | MW | Aliphatic Index | PI | Gravy | Predicted Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHBRA108g00020 | C. braunii | II | 3270 | 1089 | 121,577.68 | 71.84 | 8.73 | −0.652 | nucl |

| CHBRA95g00810 | C. braunii | II | 4116 | 1371 | 151,524.42 | 67.39 | 5.68 | −0.694 | nucl |

| Pum0671s0001.1 | P. umbilicalis | II | 1914 | 637 | 66,498.18 | 82.35 | 9.56 | −0.101 | chlo |

| Pum0488s0003.1 | P. umbilicalis | II | 1848 | 615 | 63,911.07 | 87.54 | 5.14 | 0.024 | cyto |

| Pp6c8_8830 | P. patens | I | 3126 | 1041 | 116,706.17 | 70.93 | 8.72 | −0.648 | chlo |

| Pp6c22_6780 | P. patens | II | 2286 | 761 | 85,951.74 | 77.27 | 6.65 | −0.691 | cyto |

| Pp6c1_11770 | P. patens | III | 5136 | 1711 | 188,430.86 | 73.30 | 6.04 | −0.476 | nucl |

| Sc11G012440.1 | S. caninervis | I | 3105 | 1034 | 116,281.36 | 69.63 | 8.55 | −0.710 | chlo |

| Sc01G005650.1 | S. caninervis | II | 2067 | 688 | 77,372.43 | 74.11 | 5.49 | −0.688 | nucl |

| Sc01G005680.1 | S. caninervis | II | 2076 | 691 | 78,442.27 | 75.15 | 6.81 | −0.630 | nucl |

| Dicom.03G037600.1 | D. complanatum | I | 3144 | 1047 | 117,999.89 | 77.03 | 8.5 | −0.549 | chlo |

| Dicom.12G054800.1 | D. complanatum | II | 1845 | 614 | 69,747.59 | 81.30 | 7.20 | −0.527 | cyto |

| Dicom.12G082200.1 | D. complanatum | II | 1410 | 469 | 53,469.98 | 71.13 | 8.38 | −0.574 | cyto |

| Dicom.07G034900.1 | D. complanatum | III | 2340 | 779 | 89,289.41 | 79.24 | 5.43 | −0.508 | cyto |

| Thupl.29380114s0010.1 | T. plicata | I | 3030 | 1009 | 115,201.4 | 76.12 | 8.6 | −0.72 | nucl |

| Thupl.29377528s0001.1 | T. plicata | II | 2160 | 719 | 81,838.94 | 77.36 | 7.54 | −0.641 | cyto |

| Aqcoe5G031900.1 | A. coerulea | I | 3015 | 1004 | 112,424.41 | 73.87 | 8.79 | −0.587 | nucl |

| Aqcoe2G291300.1 | A. coerulea | II | 2130 | 709 | 80,559.18 | 80.28 | 8.62 | −0.572 | nucl |

| Aqcoe2G291400.1 | A. coerulea | II | 1491 | 496 | 56,318.7 | 83.73 | 7.88 | −0.329 | vacu |

| Aqcoe1G448000.1 | A. coerulea | III | 2466 | 821 | 92,095.57 | 76.15 | 5.35 | −0.514 | cyto |

| AT2G31320.1 | A. thaliana | I | 2952 | 983 | 111,233 | 71.63 | 8.8 | −0.645 | nucl |

| AT4G02390.1 | A. thaliana | II | 1914 | 637 | 72,175.67 | 77.27 | 5.92 | −0.602 | nucl |

| AT5G22470.1 | A. thaliana | III | 2448 | 815 | 91,534.01 | 76.54 | 5.14 | −0.514 | nucl |

| OsKitaake07g113400.1 | O. sativa | I | 2934 | 977 | 110,155.92 | 76.05 | 8.85 | −0.585 | nucl |

| OsKitaake01g163300.1 | O. sativa | II | 1818 | 605 | 67,742.34 | 78.07 | 7.88 | −0.405 | cyto |

| OsKitaake01g163400.1 | O. sativa | II | 1959 | 652 | 73,333.98 | 74.66 | 6.89 | −0.613 | cyto |

| OsKitaake02g194200.1 | O. sativa | III | 2496 | 831 | 92,403.84 | 73.9 | 5.44 | −0.522 | cyto |

| ZmPHJ40.02G202600.1 | Z. mays | I | 2943 | 980 | 110,475.33 | 75.84 | 8.74 | −0.562 | chlo |

| ZmPHJ40.08G057100.2 | Z. mays | II | 1962 | 653 | 73,113.11 | 78.85 | 8.57 | −0.535 | cyto |

| ZmPHJ40.05G260500.1 | Z. mays | III | 2511 | 836 | 93,243.73 | 73.49 | 5.12 | −0.49 | nucl |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yi, K.; Yang, Q.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Gao, B. Phylogenomic Reconstruction and Functional Divergence of the PARP Gene Family Illuminate Its Role in Plant Terrestrialization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010117

Yi K, Yang Q, Ding Z, Zhang D, Wang Y, Gao B. Phylogenomic Reconstruction and Functional Divergence of the PARP Gene Family Illuminate Its Role in Plant Terrestrialization. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010117

Chicago/Turabian StyleYi, Kun, Qilin Yang, Zhen Ding, Daoyuan Zhang, Yan Wang, and Bei Gao. 2026. "Phylogenomic Reconstruction and Functional Divergence of the PARP Gene Family Illuminate Its Role in Plant Terrestrialization" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010117

APA StyleYi, K., Yang, Q., Ding, Z., Zhang, D., Wang, Y., & Gao, B. (2026). Phylogenomic Reconstruction and Functional Divergence of the PARP Gene Family Illuminate Its Role in Plant Terrestrialization. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010117