Extracellular Vesicle-Derived microRNAs: Novel Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Gastrointestinal Malignancies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Extracellular Vesicles

2.1. Biogenesis of Extracellular Vesicles

2.2. Uptake of Extracellular Vesicles

2.3. Cargo Selection

2.4. EVs as microRNA Carrier

3. Role of EVs as Biomarkers in Gastrointestinal Cancer Progression

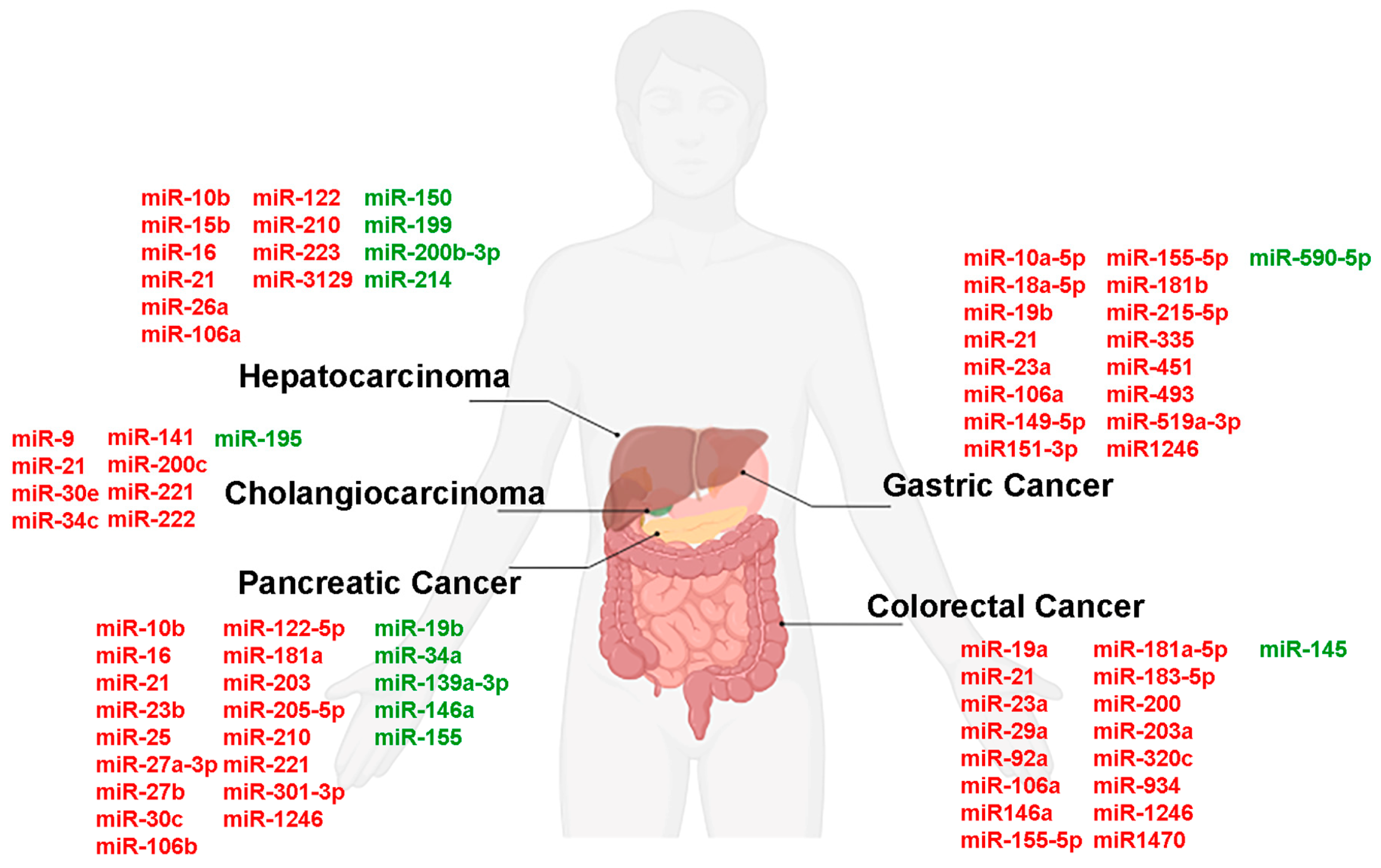

3.1. Gastric Cancer

3.2. Colorectal Cancer

3.3. Pancreatic Cancer

3.4. Hepatocarcinoma

3.5. Cholangiocarcinoma

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Argonaute | (Ago) |

| Cancer antigen 19-9 | (CA19-9) |

| Cancer-associated fibroblasts | (CAFs) |

| Carbohydrate antigen 12–5 | (CA 12-5) |

| Carbohydrate antigen 15–3 | (CA 15-3) |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | (CEA) |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | (CCA) |

| Circular RNA | (circRNA) |

| Circulating cell-free RNA | (cfDNA) |

| Circulating tumor cells | (CTCs) |

| Circulating tumor DNA | (ctDNA) |

| C-Jun N-terminal kinase | (JNK) |

| Colorectal cancer | (CRC) |

| Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport | (ESCRT) |

| Epidermal growth factor receptor | (EGFR) |

| Epithelial-mesenchymal transition | (EMT) |

| Extracellular vesicles | (EVs) |

| Extracellular vesicles derived from gastrointestinal | (GI-Evs) |

| Factor forkhead box O1 | (FOXO1) |

| Gastric cancer | (GC) |

| Gastrointestinal | (GI) |

| Hepatocarcinoma | (HCC) |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins | (hnRNPs) |

| Intraluminal vesicles | (ILVs) |

| Log non-coding RNAs | (lncRNAs) |

| Mammalian target of rapamycin | (mTOR) |

| Messenger RNAs | (mRNAs) |

| Microvesicles | (MVs) |

| mir-34a coated with exosomes | (exomiR-34a) |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase | (MAPK) |

| Pancreatic cancer | (PC) |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | (PDAC) |

| Phd finger protein 6 | (PHF6) |

| Piwi-interacting RNA | (piRNA) |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoform 2 | (PDK2) |

| Regulators of G-protein signaling | (RGS) |

| RNA-binding proteins | (RBPs) |

| Small RNAs / microRNAs | (miRNA) |

| Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 | (SOCS1) |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor | (VEGF) |

| Transforming growth factor-beta | (TGF-β) |

| Tumor microenvironment | (TME) |

References

- Ben-Aharon, I.; van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; Fontana, E.; Obermannova, R.; Nilsson, M.; Lordick, F. Early-Onset Cancer in the Gastrointestinal Tract Is on the Rise-Evidence and Implications. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Abnet, C.C.; Neale, R.E.; Vignat, J.; Giovannucci, E.L.; McGlynn, K.A.; Bray, F. Global Burden of 5 Major Types of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 335–349.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucarini, V.; Nardozi, D.; Angiolini, V.; Benvenuto, M.; Focaccetti, C.; Carrano, R.; Besharat, Z.M.; Bei, R.; Masuelli, L. Tumor Microenvironment Remodeling in Gastrointestinal Cancer: Role of miRNAs as Biomarkers of Tumor Invasion. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petricevic, B.; Kabiljo, J.; Zirnbauer, R.; Walczak, H.; Laengle, J.; Bergmann, M. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy in gastrointestinal cancers—The new standard of care? Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 834–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Sui, S.; Goel, A. Extracellular vesicles associated microRNAs: Their biology and clinical significance as biomarkers in gastrointestinal cancers. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2024, 99, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Quadri, S.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Zheng, L. New Development of Biomarkers for Gastrointestinal Cancers: From Neoplastic Cells to Tumor Microenvironment. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, A.R.; Leshchiner, I.; Elagina, L.; Goyal, L.; Levovitz, C.; Siravegna, G.; Livitz, D.; Rhrissorrakrai, K.; Martin, E.E.; Van Seventer, E.E.; et al. Liquid versus tissue biopsy for detecting acquired resistance and tumor heterogeneity in gastrointestinal cancers. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1415–1421, Erratum in Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapitz, A.; Azkargorta, M.; Milkiewicz, P.; Olaizola, P.; Zhuravleva, E.; Grimsrud, M.M.; Schramm, C.; Arbelaiz, A.; O’Rourke, C.J.; La Casta, A.; et al. Liquid biopsy-based protein biomarkers for risk prediction, early diagnosis, and prognostication of cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhou, M.; Xu, Y.; Gu, X.; Zou, M.; Abudushalamu, G.; Yao, Y.; Fan, X.; Wu, G. Clinical application and detection techniques of liquid biopsy in gastric cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhu, L.; Song, J.; Wang, G.; Li, P.; Li, W.; Luo, P.; Sun, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Liquid biopsy at the frontier of detection, prognosis and progression monitoring in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Khan, A.Q.; Inchakalody, V.P.; Mestiri, S.; Yoosuf, Z.; Bedhiafi, T.; El-Ella, D.M.A.; Taib, N.; Hydrose, S.; Akbar, S.; et al. Dynamic liquid biopsy components as predictive and prognostic biomarkers in colorectal cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, S.N.; Nisar, S.; Masoodi, T.; Singh, M.; Rizwan, A.; Hashem, S.; El-Rifai, W.; Bedognetti, D.; Batra, S.K.; Haris, M.; et al. Liquid biopsy: A step closer to transform diagnosis, prognosis and future of cancer treatments. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Hurley, J.; Roberts, D.; Chakrabortty, S.K.; Enderle, D.; Noerholm, M.; Breakefield, X.O.; Skog, J.K. Exosome-based liquid biopsies in cancer: Opportunities and challenges. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, M.; Kotani, A. Recent advances in extracellular vesicles in gastrointestinal cancer and lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2023, 114, 2230–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanayama, R. Emerging roles of extracellular vesicles in physiology and disease. J. Biochem. 2021, 169, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolini, A.; Ferrari, P.; Biava, P.M. Exosomes and Cell Communication: From Tumour-Derived Exosomes and Their Role in Tumour Progression to the Use of Exosomal Cargo for Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2021, 13, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urabe, F.; Kosaka, N.; Ito, K.; Kimura, T.; Egawa, S.; Ochiya, T. Extracellular vesicles as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2020, 318, C29–C39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.T.; Johnstone, R.M. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: Selective externalization of the receptor. Cell 1983, 33, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berumen Sanchez, G.; Bunn, K.E.; Pua, H.H.; Rafat, M. Extracellular vesicles: Mediators of intercellular communication in tissue injury and disease. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 19, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maacha, S.; Bhat, A.A.; Jimenez, L.; Raza, A.; Haris, M.; Uddin, S.; Grivel, J.C. Extracellular vesicles-mediated intercellular communication: Roles in the tumor microenvironment and anti-cancer drug resistance. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, Y.J.; Tang, Y.C.; Hao, X.Y.; Xu, W.J.; Xiang, D.X.; Wu, J.Y. Apoptotic bodies for advanced drug delivery and therapy. J. Control. Release 2022, 351, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Zheng, S.; Luo, Y.; Wang, B. Exosome Theranostics: Biology and Translational Medicine. Theranostics 2018, 8, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santavanond, J.P.; Rutter, S.F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; Poon, I.K.H. Apoptotic Bodies: Mechanism of Formation, Isolation and Functional Relevance. Subcell Biochem. 2021, 97, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidtmann, M.; D’Souza-Schorey, C. Extracellular Vesicles: Biological Packages That Modulate Tumor Cell Invasion. Cancers 2023, 15, 5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldolesi, J. Exosomes and Ectosomes in Intercellular Communication. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R435–R444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, A.C.; Dawson, T.R.; Di Vizio, D.; Weaver, A.M. Context-specific regulation of extracellular vesicle biogenesis and cargo selection. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 454–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, J.H. The emerging roles of extracellular vesicles as intercellular messengers in liver physiology and pathology. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2022, 28, 706–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hade, M.D.; Suire, C.N.; Mossell, J.; Suo, Z. Extracellular vesicles: Emerging frontiers in wound healing. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 2102–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzas, E.I. The roles of extracellular vesicles in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xia, J.; Yang, L.; Dai, J.; He, L. Recent progress in exosome research: Isolation, characterization and clinical applications. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023, 30, 1051–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Q.; Tang, T.T.; Tang, R.N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.L.; Yang, H.B.; Song, J.; Yang, Q.; Qin, S.F.; Chen, F.; et al. A comprehensive evaluation of stability and safety for HEK293F-derived extracellular vesicles as promising drug delivery vehicles. J. Control. Release 2025, 382, 113673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, N.; Knight, R.; Robertson, S.Y.T.; Dos Santos, A.; Zhang, C.; Ma, C.; Xu, J.; Zheng, J.; Deng, S.X. Stability and Function of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Immortalized Human Corneal Stromal Stem Cells: A Proof of Concept Study. AAPS J. 2022, 25, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Chen, K.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Lin, L.; Shao, Y.; Gao, L.; Yin, H.; Cui, C.; et al. DNA in serum extracellular vesicles is stable under different storage conditions. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Zhu, Y.; Ni, J.; Thompson, J.; Malouf, D.; Bucci, J.; Graham, P.; Li, Y. Extracellular vesicles: The next generation of biomarkers for liquid biopsy-based prostate cancer diagnosis. Theranostics 2020, 10, 2309–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhom, K.; Obi, P.O.; Saleem, A. A Review of Exosomal Isolation Methods: Is Size Exclusion Chromatography the Best Option? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; He, W.; Zheng, L.; Fan, X.; Hu, T.Y. Toward Clarity in Single Extracellular Vesicle Research: Defining the Field and Correcting Missteps. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 16193–16203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coumans, F.A.W.; Brisson, A.R.; Buzas, E.I.; Dignat-George, F.; Drees, E.E.E.; El-Andaloussi, S.; Emanueli, C.; Gasecka, A.; Hendrix, A.; Hill, A.F.; et al. Methodological Guidelines to Study Extracellular Vesicles. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 1632–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, A.; Boutros, M. Extracellular vesicles and oncogenic signaling. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinger, S.A.; Abner, J.J.; Franklin, J.L.; Jeppesen, D.K.; Coffey, R.J.; Patton, J.G. Rab13 regulates sEV secretion in mutant KRAS colorectal cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.; Atukorala, I.; Mathivanan, S. Biogenesis of Extracellular Vesicles. Subcell. Biochem. 2021, 97, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarenko, I. Extracellular Vesicles: Recent Developments in Technology and Perspectives for Cancer Liquid Biopsy. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2020, 215, 319–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, R.M.; Adam, M.; Hammond, J.R.; Orr, L.; Turbide, C. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes). J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 9412–9420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huotari, J.; Helenius, A. Endosome maturation. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 3481–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, M.; Martin-Jaular, L.; Lavieu, G.; Thery, C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaldo, C.; Terri, M.; Riccioni, V.; Battistelli, C.; Bordoni, V.; D’Offizi, G.; Prado, M.G.; Trionfetti, F.; Vescovo, T.; Tartaglia, E.; et al. Fibrogenic signals persist in DAA-treated HCV patients after sustained virological response. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellini, L.; Palombo, R.; Riccioni, V.; Paronetto, M.P. Oncogenic Dysregulation of Circulating Noncoding RNAs: Novel Challenges and Opportunities in Sarcoma Diagnosis and Treatment. Cancers 2022, 14, 4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsergent, E.; Grisard, E.; Buchrieser, J.; Schwartz, O.; Thery, C.; Lavieu, G. Quantitative characterization of extracellular vesicle uptake and content delivery within mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, P.; Mathivanan, S. Extracellular Vesicles Biogenesis, Cargo Sorting and Implications in Disease Conditions. Cells 2023, 12, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; He, B.; Jin, H. Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles from Arabidopsis. Curr. Protoc. 2022, 2, e352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, S.; Wilkey, D.W.; Milhem, M.; Merchant, M.; Godwin, A.K. Insights into the Proteome of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors-Derived Exosomes Reveals New Potential Diagnostic Biomarkers. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2018, 17, 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, S.; Kang, M.H.; Qasim, M.; Khan, K.; Kim, J.H. Biogenesis, Membrane Trafficking, Functions, and Next Generation Nanotherapeutics Medicine of Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 3357–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.M.; Lazaro-Ibanez, E.; Gunnarsson, A.; Dhande, A.; Daaboul, G.; Peacock, B.; Osteikoetxea, X.; Salmond, N.; Friis, K.P.; Shatnyeva, O.; et al. Quantification of protein cargo loading into engineered extracellular vesicles at single-vesicle and single-molecule resolution. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinger, S.A.; Cha, D.J.; Franklin, J.L.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Dou, Y.; Ping, J.; Shu, L.; Prasad, N.; Levy, S.; Zhang, B.; et al. Diverse Long RNAs Are Differentially Sorted into Extracellular Vesicles Secreted by Colorectal Cancer Cells. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 715–725.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, I.K.; Wood, M.J.A.; Fuhrmann, G. Extracellular vesicles as a next-generation drug delivery platform. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, T.; Njock, M.S.; Lion, M.; Bruyr, J.; Mariavelle, E.; Galvan, B.; Boeckx, A.; Struman, I.; Dequiedt, F. Sorting and packaging of RNA into extracellular vesicles shape intracellular transcript levels. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, E.; Bai, J.; Zhang, K.; Yu, H.; Guo, Y. Genomic Variants Disrupt miRNA-mRNA Regulation. Chem. Biodivers 2022, 19, e202200623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambros, V.; Bartel, B.; Bartel, D.P.; Burge, C.B.; Carrington, J.C.; Chen, X.; Dreyfuss, G.; Eddy, S.R.; Griffiths-Jones, S.; Marshall, M.; et al. A uniform system for microRNA annotation. RNA 2003, 9, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Martin, R.; Wang, G.; Brandao, B.B.; Zanotto, T.M.; Shah, S.; Kumar Patel, S.; Schilling, B.; Kahn, C.R. MicroRNA sequence codes for small extracellular vesicle release and cellular retention. Nature 2022, 601, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, B.; Nie, Z.; Duan, L.; Xiong, Q.; Jin, Z.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y. The role of m6A modification in the biological functions and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, R.; Chu, C.; Liu, G.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Liu, H. m(6)A reader hnRNPA2B1 drives multiple myeloma osteolytic bone disease. Theranostics 2022, 12, 7760–7774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.M.; Ma, L.; Schekman, R. Selective sorting of microRNAs into exosomes by phase-separated YBX1 condensates. eLife 2021, 10, e71982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabiati, M.; Salvadori, C.; Basta, G.; Del Turco, S.; Aretini, P.; Cecchettini, A.; Del Ry, S. miRNA and long non-coding RNA transcriptional expression in hepatocellular carcinoma cell line-secreted extracellular vesicles. Clin. Exp. Med. 2022, 22, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, R.; Palini, S.; Vento, M.E.; La Ferlita, A.; Lo Faro, M.J.; Caroppo, E.; Borzi, P.; Falzone, L.; Barbagallo, D.; Ragusa, M.; et al. Identification of extracellular vesicles and characterization of miRNA expression profiles in human blastocoel fluid. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloudizargari, M.; Hekmatirad, S.; Mofarahe, Z.S.; Asghari, M.H. Exosomal microRNA panels as biomarkers for hematological malignancies. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2021, 45, 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaser, M.C.; Aikawa, E. Differential miRNA Loading Underpins Dual Harmful and Protective Roles for Extracellular Vesicles in Atherogenesis. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 467–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groven, R.V.M.; Greven, J.; Mert, U.; Horst, K.; Zhao, Q.; Blokhuis, T.J.; Huber-Lang, M.; Hildebrand, F.; van Griensven, M. Circulating miRNA expression in extracellular vesicles is associated with specific injuries after multiple trauma and surgical invasiveness. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1273612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jin, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X. Exosomal miRNAs: Key Regulators of the Tumor Microenvironment and Cancer Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucotti, S.; Kenific, C.M.; Zhang, H.; Lyden, D. Extracellular vesicles and particles impact the systemic landscape of cancer. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e109288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Thakur, B.K.; Weiss, J.M.; Kim, H.S.; Peinado, H.; Lyden, D. Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer: Cell-to-Cell Mediators of Metastasis. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R.; Maresh, G.; Zhang, X.; Salomon, C.; Hooper, J.; Margolin, D.; Li, L. The Emerging Roles of Extracellular Vesicles As Communication Vehicles within the Tumor Microenvironment and Beyond. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, N.; Hermann, P.C.; Eiseler, T.; Seufferlein, T. Emerging Roles of Small Extracellular Vesicles in Gastrointestinal Cancer Research and Therapy. Cancers 2024, 16, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Shan, Z.; Sun, F.; Tan, Y.; Tong, Y.; Qiu, Y. Extracellular vesicles in gastric cancer: Role of exosomal lncRNA and microRNA as diagnostic and therapeutic targets. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1158839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchetti, D.; Zurlo, I.V.; Colella, F.; Ricciardi-Tenore, C.; Di Salvatore, M.; Tortora, G.; De Maria, R.; Giuliante, F.; Cassano, A.; Basso, M.; et al. Mutational status of plasma exosomal KRAS predicts outcome in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greening, D.W.; Xu, R.; Rai, A.; Suwakulsiri, W.; Chen, M.; Simpson, R.J. Clinical relevance of extracellular vesicles in cancer—therapeutic and diagnostic potential. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 22, 924–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.; Tandon, M.; Alevizos, I.; Illei, G.G. The majority of microRNAs detectable in serum and saliva is concentrated in exosomes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Han, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Song, J.; Gao, Z.; Qian, H.; Jin, J.; Liang, Z. Exosomal circRNAs in gastrointestinal cancer: Role in occurrence, development, diagnosis and clinical application (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2024, 51, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Luo, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; He, M. Cancer spheroids derived exosomes reveal more molecular features relevant to progressed cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2021, 26, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Zeng, W.; Feng, K.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, P.; Chen, F.; Zhang, W.; Di, L.; Wang, R. Extracellular vesicles as biomarkers and drug delivery systems for tumor. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 3460–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shen, H.; Zhang, N. Advances in extracellular vesicle (EV) biomarkers for precision diagnosis and therapeutic in colorectal cancer. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1581015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; Baba, S.K.; Sadida, H.Q.; Marzooqi, S.A.; Jerobin, J.; Altemani, F.H.; Algehainy, N.; Alanazi, M.A.; Abou-Samra, A.B.; Kumar, R.; et al. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, P.; Chen, L.; Yuan, X.; Luo, Q.; Liu, Y.; Xie, G.; Ma, Y.; Shen, L. Exosomal transfer of tumor-associated macrophage-derived miR-21 confers cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 36, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaka, N.; Iguchi, H.; Hagiwara, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Takeshita, F.; Ochiya, T. Neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2)-dependent exosomal transfer of angiogenic microRNAs regulate cancer cell metastasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 10849–10859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Li, Y.; Pan, Y.; Lan, X.; Song, F.; Sun, J.; Zhou, K.; Liu, X.; Ren, X.; Wang, F.; et al. Cancer-derived exosomal miR-25-3p promotes pre-metastatic niche formation by inducing vascular permeability and angiogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldenmaier, M.; Seibold, T.; Seufferlein, T.; Eiseler, T. Pancreatic Cancer Small Extracellular Vesicles (Exosomes): A Tale of Short- and Long-Distance Communication. Cancers 2021, 13, 4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irmer, B.; Chandrabalan, S.; Maas, L.; Bleckmann, A.; Menck, K. Extracellular Vesicles in Liquid Biopsies as Biomarkers for Solid Tumors. Cancers 2023, 15, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsina, M.; Arrazubi, V.; Diez, M.; Tabernero, J. Current developments in gastric cancer: From molecular profiling to treatment strategy. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, R.E.; Al Hallak, M.N.; Diab, M.; Azmi, A.S. Gastric cancer: A comprehensive review of current and future treatment strategies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39, 1179–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, E.C.; Nilsson, M.; Grabsch, H.I.; van Grieken, N.C.; Lordick, F. Gastric cancer. Lancet 2020, 396, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, D.R.; Li, G.G.; Wang, H.H.; Li, X.W.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.L.; Chen, L. CD97 promotes gastric cancer cell proliferation and invasion through exosome-mediated MAPK signaling pathway. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 6215–6228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Cai, S.; Zhang, C.D.; Li, Y.S. The biological role of extracellular vesicles in gastric cancer metastasis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1323348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Song, C.; Zheng, L.; Xia, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y. The roles of extracellular vesicles in gastric cancer development, microenvironment, anti-cancer drug resistance, and therapy. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Cao, J.; Huang, X.; Chen, Z.; Xu, P.; Sun, G.; Xu, J.; Lv, J.; et al. Circular RNA circNRIP1 acts as a microRNA-149-5p sponge to promote gastric cancer progression via the AKT1/mTOR pathway. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Qiu, R.; Yu, S.; Xu, X.; Li, G.; Gu, R.; Tan, C.; Zhu, W.; Shen, B. Paclitaxel-resistant gastric cancer MGC-803 cells promote epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and chemoresistance in paclitaxel-sensitive cells via exosomal delivery of miR-155-5p. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 54, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Liang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.M.; Lin, X.Y. Gastric Cancer Cell-Derived Exosomal microRNA-23a Promotes Angiogenesis by Targeting PTEN. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 326, Erratum in Front. Oncol. 2022, 11, 797657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Xie, L.; Lu, C.; Gu, C.; Xia, Y.; Lv, J.; Xuan, Z.; Fang, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Gastric cancer-derived exosomal miR-519a-3p promotes liver metastasis by inducing intrahepatic M2-like macrophage-mediated angiogenesis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Wei, S.; Wei, F. Extracellular vesicles mediated gastric cancer immune response: Tumor cell death or immune escape? Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renovato-Martins, M.; Gomes, A.C.; Amorim, C.S.; Moraes, J.A. The Role of Macrophage-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Gastrointestinal Cancers. In Gastrointestinal Cancers; Morgado-Diaz, J.A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Brisbane, Austrlia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Zhang, N.; He, S.; Lu, X. Exosomal miR-106a derived from gastric cancer promotes peritoneal metastasis via direct regulation of Smad7. Cell Cycle 2020, 19, 1200–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Gong, L.; Xiao, B.; Liu, X. A serum exosomal microRNA panel as a potential biomarker test for gastric cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 493, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Bu, Z.; Zhao, F.; Xiao, D. Increased T-helper 17 cell differentiation mediated by exosome-mediated microRNA-451 redistribution in gastric cancer infiltrated T cells. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinoya, M.; Miyatani, K.; Matsumi, Y.; Sakano, Y.; Shimizu, S.; Shishido, Y.; Hanaki, T.; Kihara, K.; Matsunaga, T.; Yamamoto, M.; et al. Exosomal miR-493 suppresses MAD2L1 and induces chemoresistance to intraperitoneal paclitaxel therapy in gastric cancer patients with peritoneal metastasis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahroba, H.; Samadi, N.; Mostafazadeh, M.; Hejazi, M.S.; Sadeghi, M.R.; Hashemzadeh, S.; Eftekhar Sadat, A.T.; Karimi, A. Evaluating the presence of deregulated tumoral onco-microRNAs in serum-derived exosomes of gastric cancer patients as noninvasive diagnostic biomarkers. Bioimpacts 2022, 12, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, D.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Toden, S.; Huo, X.; Kanda, M.; Ishimoto, T.; Gu, D.; Tan, M.; Kodera, Y.; et al. Assessment of the Diagnostic Efficiency of a Liquid Biopsy Assay for Early Detection of Gastric Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2121129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.D.; Xu, Z.Y.; Hu, C.; Lv, H.; Xie, H.X.; Huang, T.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Chen, G.P.; Fu, Y.F.; Cheng, X.D. Exosomal miR-590-5p in Serum as a Biomarker for the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Gastric Cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 636566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Chen, L.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, Z. Exosomal miR-1246 in serum as a potential biomarker for early diagnosis of gastric cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 25, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Houdt, W.J.; Hoogwater, F.J.; de Bruijn, M.T.; Emmink, B.L.; Nijkamp, M.W.; Raats, D.A.; van der Groep, P.; van Diest, P.; Borel Rinkes, I.H.; Kranenburg, O. Oncogenic KRAS desensitizes colorectal tumor cells to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition and activation. Neoplasia 2010, 12, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Yang, F.; Cheng, R.; Chen, X.; Cui, S.; Gu, Y.; Sun, W.; You, C.; Liu, Z.; et al. miR-19a promotes colorectal cancer proliferation and migration by targeting TIA1. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Wang, F.; Jiang, H.; Xu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z. MicroRNA-145 suppresses cell migration and invasion by targeting paxillin in human colorectal cancer cells. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 1328–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tong, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, B. miR-145-5p restrained cell growth, invasion, migration and tumorigenesis via modulating RHBDD1 in colorectal cancer via the EGFR-associated signaling pathway. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2019, 117, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, A.; Wang, X.; Gu, C.; Liu, W.; Sun, J.; Zeng, B.; Chen, C.; Ji, P.; Wu, J.; Quan, W.; et al. Exosomal miR-183-5p promotes angiogenesis in colorectal cancer by regulation of FOXO1. Aging 2020, 12, 8352–8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, S.; Liu, D.; Zhou, J. LINC01915 Facilitates the Conversion of Normal Fibroblasts into Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Induced by Colorectal Cancer-Derived Extracellular Vesicles through the miR-92a-3p/KLF4/CH25H Axis. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 5255–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, B.J.; Dennett, E.R.; Danielson, K.M. Circulating Extracellular Vesicle MicroRNA as Diagnostic Biomarkers in Early Colorectal Cancer-A Review. Cancers 2019, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, N.O.; Heishima, K.; Akao, Y.; Senda, T. Extracellular Vesicles Containing MicroRNA-92a-3p Facilitate Partial Endothelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Angiogenesis in Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Dou, R.; Wei, C.; Liu, K.; Shi, D.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Xiong, B. Tumor-derived exosomal microRNA-106b-5p activates EMT-cancer cell and M2-subtype TAM interaction to facilitate CRC metastasis. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 2088–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Si, M.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X.; Cui, S.; Qu, X.; Yu, X. Exosomal miR-146a-5p and miR-155-5p promote CXCL12/CXCR7-induced metastasis of colorectal cancer by crosstalk with cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, W.; Wei, K.; Wu, Y.; Qiu, Q.; Zhu, H.; Mao, L.; Shi, X.; Zhang, S.; Shi, Y.; Tao, S.; et al. Colorectal cancer tumor cell-derived exosomal miR-203a-3p promotes CRC metastasis by targeting PTEN-induced macrophage polarization. Gene 2023, 885, 147692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Mi, Y.; Guan, B.; Zheng, B.; Wei, P.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, S.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Tumor-derived exosomal miR-934 induces macrophage M2 polarization to promote liver metastasis of colorectal cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 156, Erratum in J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Ding, L.; Zhang, D.; Shi, G.; Xu, Q.; Shen, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Hou, Y. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts promote the stemness and chemoresistance of colorectal cancer by transferring exosomal lncRNA H19. Theranostics 2018, 8, 3932–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, G.; Gomez-Autet, M.; Morales, P.; Rebassa, J.B.; Llinas Del Torrent, C.; Jagerovic, N.; Pardo, L.; Franco, R. Homodimerization of CB(2) cannabinoid receptor triggered by a bivalent ligand enhances cellular signaling. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 208, 107363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata-Kawata, H.; Izumiya, M.; Kurioka, D.; Honma, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Furuta, K.; Gunji, T.; Ohta, H.; Okamoto, H.; Sonoda, H.; et al. Circulating exosomal microRNAs as biomarkers of colon cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.; Sharma, S.; Obermair, A.; Salomon, C. Extracellular Vesicle-Associated miRNAs and Chemoresistance: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Sanchez, D.; Arriaga-Canon, C.; Pedroza-Torres, A.; De La Rosa-Velazquez, I.A.; Gonzalez-Barrios, R.; Contreras-Espinosa, L.; Montiel-Manriquez, R.; Castro-Hernandez, C.; Fragoso-Ontiveros, V.; Alvarez-Gomez, R.M.; et al. The Promising Role of miR-21 as a Cancer Biomarker and Its Importance in RNA-Based Therapeutics. Mol. Ther. Nucleic. Acids 2020, 20, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, T.; Sugimachi, K.; Iinuma, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Kurashige, J.; Sawada, G.; Ueda, M.; Uchi, R.; Ueo, H.; Takano, Y.; et al. Exosomal microRNA in serum is a novel biomarker of recurrence in human colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Mi, Y.; Zheng, B.; Wei, P.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Cai, S.; Li, X.; Li, D. Highly-metastatic colorectal cancer cell released miR-181a-5p-rich extracellular vesicles promote liver metastasis by activating hepatic stellate cells and remodelling the tumour microenvironment. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.K.; Hsu, H.C.; Liu, Y.H.; Tsai, W.S.; Ma, C.P.; Chen, Y.T.; Tan, B.C.; Lai, Y.Y.; Chang, I.Y.; Yang, C.; et al. EV-miRome-wide profiling uncovers miR-320c for detecting metastatic colorectal cancer and monitoring the therapeutic response. Cell. Oncol. 2022, 45, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Eng, C.; Shen, J.; Lu, Y.; Takata, Y.; Mehdizadeh, A.; Chang, G.J.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A.; Li, Y.; Chang, P.; et al. Serum exosomal miR-4772-3p is a predictor of tumor recurrence in stage II and III colon cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 76250–76260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siveen, K.S.; Raza, A.; Ahmed, E.I.; Khan, A.Q.; Prabhu, K.S.; Kuttikrishnan, S.; Mateo, J.M.; Zayed, H.; Rasul, K.; Azizi, F.; et al. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles as Modulators of the Tumor Microenvironment, Metastasis and Drug Resistance in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senfter, D.; Holzner, S.; Kalipciyan, M.; Staribacher, A.; Walzl, A.; Huttary, N.; Krieger, S.; Brenner, S.; Jager, W.; Krupitza, G.; et al. Loss of miR-200 family in 5-fluorouracil resistant colon cancer drives lymphendothelial invasiveness in vitro. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 3689–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lin, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, B.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, Z.; Li, G.; Xie, L. Exosomal miR-1470 is a diagnostic biomarker and promotes cell proliferation and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.P. Pancreatic cancer epidemiology: Understanding the role of lifestyle and inherited risk factors. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.I.; O’Reilly, E.M. Therapeutic developments in pancreatic cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 21, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Ren, H. Precision treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2024, 585, 216636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Yang, G.; Feng, M.; Zheng, S.; Cao, Z.; You, L.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Y. Extracellular vesicles as mediators of the progression and chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer and their potential clinical applications. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capula, M.; Peran, M.; Xu, G.; Donati, V.; Yee, D.; Gregori, A.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Giovannetti, E.; Deng, D. Role of drug catabolism, modulation of oncogenic signaling and tumor microenvironment in microbe-mediated pancreatic cancer chemoresistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 2022, 64, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Rong, Y.; Kuang, T.; Xu, X.; Wu, W.; Wang, D.; Lou, W. Exosomal miRNA-106b from cancer-associated fibroblast promotes gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer. Exp. Cell Res. 2019, 383, 111543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, P.K.; Shanmugam, P.; Karn, V.; Gupta, S.; Mishra, R.; Rustagi, S.; Chouhan, M.; Verma, D.; Jha, N.K.; Kumar, S. Extracellular Vesicular miRNA in Pancreatic Cancer: From Lab to Therapy. Cancers 2024, 16, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Sastre, A.; Lubeseder-Martellato, C.; Engleitner, T.; Steiger, K.; Zhong, S.; Desztics, J.; Ollinger, R.; Rad, R.; Schmid, R.M.; Hermeking, H.; et al. Mir34a constrains pancreatic carcinogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Tao, H.; Xu, H.; Li, C.; Qiao, G.; Guo, M.; Cao, S.; Liu, M.; Lin, X. Exosomes-Coated miR-34a Displays Potent Antitumor Activity in Pancreatic Cancer Both in vitro and in vivo. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 14, 3495–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reale, A.; Khong, T.; Spencer, A. Extracellular Vesicles and Their Roles in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Wang, M.; McElyea, S.D.; Sherman, S.; House, M.; Korc, M. A microRNA signature in circulating exosomes is superior to exosomal glypican-1 levels for diagnosing pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017, 393, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolimetti, G.; Pelisenco, I.A.; Eusebi, L.H.; Ricci, C.; Cavina, B.; Kurelac, I.; Verri, T.; Calcagnile, M.; Alifano, P.; Salvi, A.; et al. Dysregulation of a Subset of Circulating and Vesicle-Associated miRNA in Pancreatic Cancer. Noncoding RNA 2024, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, A.M.; Mattar, S.B.; Amatuzzi, R.F.; Chammas, R.; Uno, M.; Zanette, D.L.; Aoki, M.N. Plasma Exosome-Derived microRNAs as Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers in Brazilian Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesteruk, K.; Levink, I.J.M.; de Vries, E.; Visser, I.J.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Cahen, D.L.; Fuhler, G.M.; Bruno, M.J. Extracellular vesicle-derived microRNAs in pancreatic juice as biomarkers for detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreatology 2022, 22, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Ye, N.; Li, F.; Zhan, H.; Chen, S.; Xu, J. Plasma-Derived Exosome MiR-19b Acts as a Diagnostic Marker for Pancreatic Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 739111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Luo, G.; Zhang, K.; Cao, J.; Huang, C.; Jiang, T.; Liu, B.; Su, L.; Qiu, Z. Hypoxic Tumor-Derived Exosomal miR-301a Mediates M2 Macrophage Polarization via PTEN/PI3Kgamma to Promote Pancreatic Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 4586–4598, Erratum in Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasimi Shad, A.; Fanoodi, A.; Maharati, A.; Akhlaghipour, I.; Moghbeli, M. Molecular mechanisms of microRNA-301a during tumor progression and metastasis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 247, 154538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Vandenboom, T.G., 2nd; Wang, Z.; Kong, D.; Ali, S.; Philip, P.A.; Sarkar, F.H. miR-146a suppresses invasion of pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 1486–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.H.; Pauklin, S. Extracellular vesicles in pancreatic cancer progression and therapies. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forner, A.; Reig, M.; Bruix, J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2018, 391, 1301–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinero, F.; Dirchwolf, M.; Pessoa, M.G. Biomarkers in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Diagnosis, Prognosis and Treatment Response Assessment. Cells 2020, 9, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.S.; Liao, C.J.; Huang, Y.H.; Yeh, C.T.; Chen, C.Y.; Tang, H.C.; Chang, C.C.; Lin, K.H. Functional and Clinical Significance of Dysregulated microRNAs in Liver Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.P.; Wang, C.Y.; Jin, X.H.; Li, M.; Wang, F.W.; Huang, W.J.; Yun, J.P.; Xu, R.H.; Cai, Q.Q.; Xie, D. Acidic Microenvironment Up-Regulates Exosomal miR-21 and miR-10b in Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma to Promote Cancer Cell Proliferation and Metastasis. Theranostics 2019, 9, 1965–1979, Erratum in Theranostics 2021, 11, 6522–6523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.Q.; Yang, X.W.; Chen, Y.B.; Zhang, D.W.; Jiang, X.F.; Xue, P. Exosomal miR-21 regulates the TETs/PTENp1/PTEN pathway to promote hepatocellular carcinoma growth. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 148, Erratum in Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Ren, H.; Dai, B.; Li, J.; Shang, L.; Huang, J.; Shi, X. Hepatocellular carcinoma-derived exosomal miRNA-21 contributes to tumor progression by converting hepatocyte stellate cells to cancer-associated fibroblasts. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 324, Erratum in J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Mao, F.; Guo, L.; Shi, J.; Wu, M.; Cheng, S.; Guo, W. Tumor cells derived-extracellular vesicles transfer miR-3129 to promote hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by targeting TXNIP. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moh-Moh-Aung, A.; Fujisawa, M.; Ito, S.; Katayama, H.; Ohara, T.; Ota, Y.; Yoshimura, T.; Matsukawa, A. Decreased miR-200b-3p in cancer cells leads to angiogenesis in HCC by enhancing endothelial ERG expression. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorop, A.; Constantinescu, D.; Cojocaru, F.; Dinischiotu, A.; Cucu, D.; Dima, S.O. Exosomal microRNAs as Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakral, S.; Ghoshal, K. miR-122 is a unique molecule with great potential in diagnosis, prognosis of liver disease, and therapy both as miRNA mimic and antimir. Curr. Gene Ther. 2015, 15, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramantieri, L.; Giovannini, C.; Piscaglia, F.; Fornari, F. MicroRNAs as Modulators of Tumor Metabolism, Microenvironment, and Immune Response in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2021, 8, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.J.; Fang, J.H.; Yang, X.J.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zhuang, S.M. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell-Secreted Exosomal MicroRNA-210 Promotes Angiogenesis In Vitro and In Vivo. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 11, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluschinski, M.; Loosen, S.; Kordes, C.; Keitel, V.; Kuebart, A.; Brandenburger, T.; Scholer, D.; Wammers, M.; Neumann, U.P.; Luedde, T.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles as Markers of Liver Function: Optimized Workflow for Biomarker Identification in Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Qin, L.; Hu, R. Development and validation of serum exosomal microRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimkhanloo, H.; Mohammadi-Yeganeh, S.; Hadavi, R.; Koochaki, A.; Paryan, M. Potential role of miR-214 in beta-catenin gene expression within hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 7429–7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, N.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, M. Silencing of lncRNA PVT1 by miR-214 inhibits the oncogenic GDF15 signaling and suppresses hepatocarcinogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 521, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonkaew, B.; Satthawiwat, N.; Pinjaroen, N.; Chuaypen, N.; Tangkijvanich, P. Circulating Extracellular Vesicle-Derived microRNAs as Novel Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers for Non-Viral-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Zhang, T.; Lou, G.; Liu, Y. Role of miR-223 in the pathophysiology of liver diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banales, J.M.; Marin, J.J.G.; Lamarca, A.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Khan, S.A.; Roberts, L.R.; Cardinale, V.; Carpino, G.; Andersen, J.B.; Braconi, C.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: The next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 557–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, L.; Sato, K.; Alpini, G.; Strazzabosco, M. The Tumor Microenvironment in Cholangiocarcinoma Progression. Hepatology 2021, 73, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, R.; Yin, Y.; Luo, H.; Cao, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Luo, H.; Zeng, X.; Wang, D. Clinical significance of small extracellular vesicles in cholangiocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1334592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.Y.; Ahn, K.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, T.S.; Baek, W.K.; Suh, S.I.; Kang, K.J. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers in bile-derived exosomes of cholangiocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2021, 101, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigehara, K.; Yokomuro, S.; Ishibashi, O.; Mizuguchi, Y.; Arima, Y.; Kawahigashi, Y.; Kanda, T.; Akagi, I.; Tajiri, T.; Yoshida, H.; et al. Real-time PCR-based analysis of the human bile microRNAome identifies miR-9 as a potential diagnostic biomarker for biliary tract cancer. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, C.; Frese, R.; Grams, M.; Fehring, L. Emerging Role of microRNA Dysregulation in Diagnosis and Prognosis of Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Genes 2022, 13, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaizola, P.; Lee-Law, P.Y.; Arbelaiz, A.; Lapitz, A.; Perugorria, M.J.; Bujanda, L.; Banales, J.M. MicroRNAs and extracellular vesicles in cholangiopathies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 1293–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yao, L.; Li, G.; Ma, D.; Sun, C.; Gao, S.; Zhang, P.; Gao, F. miR-221 Promotes Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition through Targeting PTEN and Forms a Positive Feedback Loop with beta-catenin/c-Jun Signaling Pathway in Extra-Hepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Chen, G.; Xia, Q.; Shao, S.; Fang, H. Exosomal miR-200 family as serum biomarkers for early detection and prognostic prediction of cholangiocarcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2019, 12, 3870–3876. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Ning, Z.; Ma, L.; Liu, W.; Shao, C.; Shu, Y.; Shen, H. Exosomal miRNAs and miRNA dysregulation in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Hong, J.; Wu, J. Potential of extracellular vesicles and exosomes as diagnostic markers for cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2022, 11, 436–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Otake, S.; Tamaki, Y.; Okada, M.; Aso, K.; Makino, Y.; Fujii, S.; Ota, T.; Haneda, M. Extracellular vesicle-encapsulated miR-30e suppresses cholangiocarcinoma cell invasion and migration via inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 16400–16417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Piontek, K.; Ishida, M.; Fausther, M.; Dranoff, J.A.; Fu, R.; Mezey, E.; Gould, S.J.; Fordjour, F.K.; Meltzer, S.J.; et al. Extracellular vesicles carry microRNA-195 to intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and improve survival in a rat model. Hepatology 2017, 65, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, M.A.; Ludwig, R.G.; Garcia-Martin, R.; Brandao, B.B.; Kahn, C.R. Extracellular miRNAs: From Biomarkers to Mediators of Physiology and Disease. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 656–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| miRNAs | Clinical Application | Biological Role | Sample | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-10a-5p | Diagnostic biomarker | Cell proliferation, metastasis and apoptosis inhibition | Serum | [104] |

| miR-18a-5p | Early diagnostic biomarker | Cell proliferation and metastasis | Serum | [104,105] |

| miR-19b | Early diagnostic biomarker | High levels in GC; cancer progression | Serum | [101,104] |

| miR-21 | Prognostic biomarker | Cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis inhibition | Cell culture | [83,99] |

| miR-23a | Diagnostic biomarker | Promotion of angiogenesis via the repression of PTEN | Cell culture | [96] |

| miR-106a | Early diagnostic biomarker | Induction of migration and apoptosis reduction via Smad7 | Cell culture; Serum | [100,101] |

| miR-149-5p | Diagnostic and prognostic biomarker | Promotion of GC progression via the AKT1/mTOR pathway | Plasma | [94] |

| miR-151-3p | Prognostic biomarker | Tumor cell proliferation | Cell culture | [98] |

| miR-155-5p | Drug resistance | Promotion of chemoresistant phenotype | Cell culture | [95] |

| miR-181b | Early diagnostic biomarker | High levels in GC; cancer progression | Serum | [105] |

| miR-215-5p | Diagnostic biomarker | Cell cycle, cell proliferation and metastasis | Serum | [104] |

| miR-335 | Early diagnostic biomarker | High levels in GC; cancer progression | Serum | [105] |

| miR-451 | Prognostic biomarker | Increase in Th17 polarization through exosome-mediated delivery to infiltrating T cells | Serum | [102] |

| miR-493 | Prognostic biomarker | Induction of chemoresistance via MAD2L1 suppression | Peritoneal lavage fluid | [103] |

| miR-519a-3p | Diagnostic biomarker | Metastasis and angiogenesis | Cell culture | [97] |

| miR-590-5p | Diagnostic and Prognostic biomarker | High levels in GC; cancer progression | Serum | [106] |

| miR-1246 | Early diagnostic biomarker | High levels in GC; cancer progression | Serum | [107] |

| miRNAs | Clinical Application | Biological Role | Sample | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-19a | Diagnostic and prognostic biomarker | Cell proliferation and migration via TIA1 | Cancer tissue; Serum | [109,128] |

| miR-21 | Diagnostic and drug resistance biomarker | Induction of cell proliferation, metastasis and chemoresistance by targeting the PTEN/PI3K/AKT | Cell culture; Serum | [114,121,122,123,124,129] |

| miR-23a | Diagnostic biomarker | Cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis | Serum | [114,122] |

| miR-29a | Diagnostic biomarker | Upregulated in CRC and associated with disease progression | Serum | [129] |

| miR-92a | Diagnostic and prognostic biomarker | High levels in stage I-II CRC patients | Serum; Plasma; Cell culture | [113,114,115,125] |

| miR-106a | Prognostic biomarker | Induction of metastasis through promotion of EMT and TAM2 infiltration | Cell culture | [116] |

| miR-145 | Diagnostic and prognostic biomarker | Suppression of cell migration and invasion by targeting paxillin | Cell culture | [110,111] |

| miR-146a | Prognostic biomarker | Promotion of tumor metastasis through the CXCL12/CXCR7 axis | Cell culture | [117] |

| miR-155-5p | Prognostic biomarker | Promotion of tumor metastasis through the CXCL12/CXCR7 axis | Cell culture | [117] |

| miR-181a-5p | Prognostic biomarker | Promotion of tumor metastasis by activating hepatic stellate cells and remodelling TME | Plasma; Cell culture | [126] |

| miR-183-5p | Diagnostic and prognostic biomarker | High levels in CRC; cancer progression | Cell culture | [112] |

| miR-200 | Diagnostic biomarker | Promotion of 5-fluorouracil resistant | Cell culture | [130] |

| miR-203a | Prognostic biomarker | Induction of metastasis by targeting PTEN-induced macrophage polarization | Plasma | [118] |

| miR-320c | Prognostic and therapeutic biomarker | High levels in CRC; cancer progression | Plasma | [127] |

| miR-934 | Prognostic biomarker | Induction of metastasis through macrophage M2 polarization | Cancer tissue | [119] |

| miR-1246 | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in CRC; cancer progression | Serum; Plasma | [114,122] |

| miR-1470 | Diagnostic biomarker | Cell proliferation and metastasis | Serum | [131] |

| miRNAs | Clinical Application | Biological Role | Sample | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-10b | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in PC; cancer progression | Plasma | [142] |

| miR-16 | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in PC; cancer progression | Pancreatic juice and serum | [145] |

| miR-19b | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in PC; cancer progression | Plasma | [144,146] |

| miR-21 | Diagnostic biomarker | Tumor progression, metastasis, and poor prognosis | Plasma; Pancreatic juice and serum | [142,145] |

| miR-23b-2p | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in PC; cancer progression | Plasma; Serum | [143] |

| miR-25 | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in PC; cancer progression | Pancreatic juice and serum | [145] |

| miR-27a-3p | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in PC; cancer progression | Plasma; Serum | [143] |

| miR-27b | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in PC; cancer progression | Plasma | [144] |

| miR-30c | Diagnostic biomarker | Increased cell survival and proliferation | Plasma | [142] |

| miR-34a | Diagnostic biomarker | Suppression cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion | Cell culture | [140] |

| miR-106b | Drug resistance | Induction of gemcitabine resistance | Cell culture | [137] |

| miR-122-5p | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in PC; cancer progression | Plasma | [142,144] |

| miR-146a | Diagnostic and drug resistance biomarker | Suppression of cancer cell invasion | Serum; Cell culture | [135,149] |

| miR-155 | Diagnostic biomarker | Cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis | Cell culture | [150] |

| miR-181a | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in PC; cancer progression | Plasma | [142] |

| miR-193a-3p | Diagnostic biomarker | Inhibition of cell proliferation and metastasis | Plasma; Serum | [143] |

| miR-203 | Diagnostic and prognostic biomarker | Regulation of tumor cell proliferation via JAK-STAT | Cell culture | [141] |

| miR-205-5p | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in PC; cancer progression | Plasma | [144] |

| miR-210 | Drug resistance | Cell invasion and chemoresistance | Cell culture | [73] |

| miR-221 | Diagnostic biomarker | Tumor growth and apoptosis resistance through PTEN and PDCD4 | Cell culture | [138] |

| miR-221-3p | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in PC; cancer progression | Plasma; Serum | [143,144] |

| miR-301a-3p | Prognostic biomarker | Promotion of metastasis via the PTEN/PI3Kγ pathway | Cell culture; | [147,148] |

| miR-1246 | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in PC; cancer progression | Serum; Saliva | [86,135] |

| miRNAs | Clinical Application | Biological Role | Sample | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-10b | Diagnostic biomarker | Cell Proliferation and metastasis | Cell culture | [154] |

| miR-15b | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in HCC; cancer progression | Serum | [163] |

| miR-16 | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in HCC; cancer progression | Serum | [163] |

| miR-21 | Diagnostic and prognostic biomarker | High levels in HCC; cancer progression | Cell culture; Serum | [153,154,155,156,159] |

| miR-26a | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in HCC; cancer progression | Serum | [163] |

| miR-106a | Prognostic biomarker | Cell proliferation and invasion via c-Jun pathway | Serum | [164] |

| miR-122 | Diagnostic biomarker | Cell cycle progression, tumor invasion | Serum | [153,160,161]; |

| miR-150 | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in HCC; cancer progression | Serum | [163] |

| miR-199 | Diagnostic biomarker | Inhibition of cell proliferation and migration | Cancer tissues | [153] |

| miR-200b-3p | Diagnostic biomarker | Inhibition of HCC growth | Cell culture | [158] |

| miR-210 | Diagnostic biomarker | Promotion of angiogenesis | Cell culture | [162] |

| miR-214 | Diagnostic biomarker | Inhibition of cell proliferation | Cell culture | [165,166] |

| miR-223 | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in HCC; cancer progression | Serum; Plasma | [167,168] |

| miR-3129 | Prognostic biomarker | Promotion of metastasis formation by targeting TXNIP | Plasma | [157] |

| miRNAs | Clinical Application | Biological Role | Sample | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-9 | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in CCA; cancer progression | Bile | [173] |

| miR-21 | Diagnostic biomarker | Tumor progression and poor prognosis | Bile; Serum | [172,174] |

| miR-30e | Diagnosis biomarker | Cell proliferation and invasion | Cell culture | [179,180] |

| miR-34c | Diagnostic biomarker | Cell growth, invasion, and resistance | Cell culture | [179] |

| miR-141 | Diagnostic biomarker | High levels in CCA; cancer progression | Serum | [177] |

| miR-195 | Diagnostic biomarker | Inhibition of EMT | Cell culture | [181] |

| miR-200c | Diagnostic biomarker | Regulation of EMT by targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2 | Serum | [177,179] |

| miR-221 | Diagnostic biomarker | Cell cycle progression and apoptosis inhibition by targeting p27Kip1 and pro-apoptotic proteins | Cell culture | [176] |

| miR-222 | Diagnostic biomarker | Tumor progression and poor prognosis | Serum | [175] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nardozi, D.; Lucarini, V.; Angiolini, V.; Feverati, N.; Benvenuto, M.; Focaccetti, C.; Del Conte, L.; Buccitti, O.; Palumbo, C.; Cifaldi, L.; et al. Extracellular Vesicle-Derived microRNAs: Novel Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Gastrointestinal Malignancies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010010

Nardozi D, Lucarini V, Angiolini V, Feverati N, Benvenuto M, Focaccetti C, Del Conte L, Buccitti O, Palumbo C, Cifaldi L, et al. Extracellular Vesicle-Derived microRNAs: Novel Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Gastrointestinal Malignancies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleNardozi, Daniela, Valeria Lucarini, Valentina Angiolini, Nicole Feverati, Monica Benvenuto, Chiara Focaccetti, Letizia Del Conte, Olga Buccitti, Camilla Palumbo, Loredana Cifaldi, and et al. 2026. "Extracellular Vesicle-Derived microRNAs: Novel Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Gastrointestinal Malignancies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010010

APA StyleNardozi, D., Lucarini, V., Angiolini, V., Feverati, N., Benvenuto, M., Focaccetti, C., Del Conte, L., Buccitti, O., Palumbo, C., Cifaldi, L., Ferretti, E., Bei, R., & Masuelli, L. (2026). Extracellular Vesicle-Derived microRNAs: Novel Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Gastrointestinal Malignancies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010010