Investigation of the Possible Antibacterial Effects of Corticioid Fungi Against Different Bacterial Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

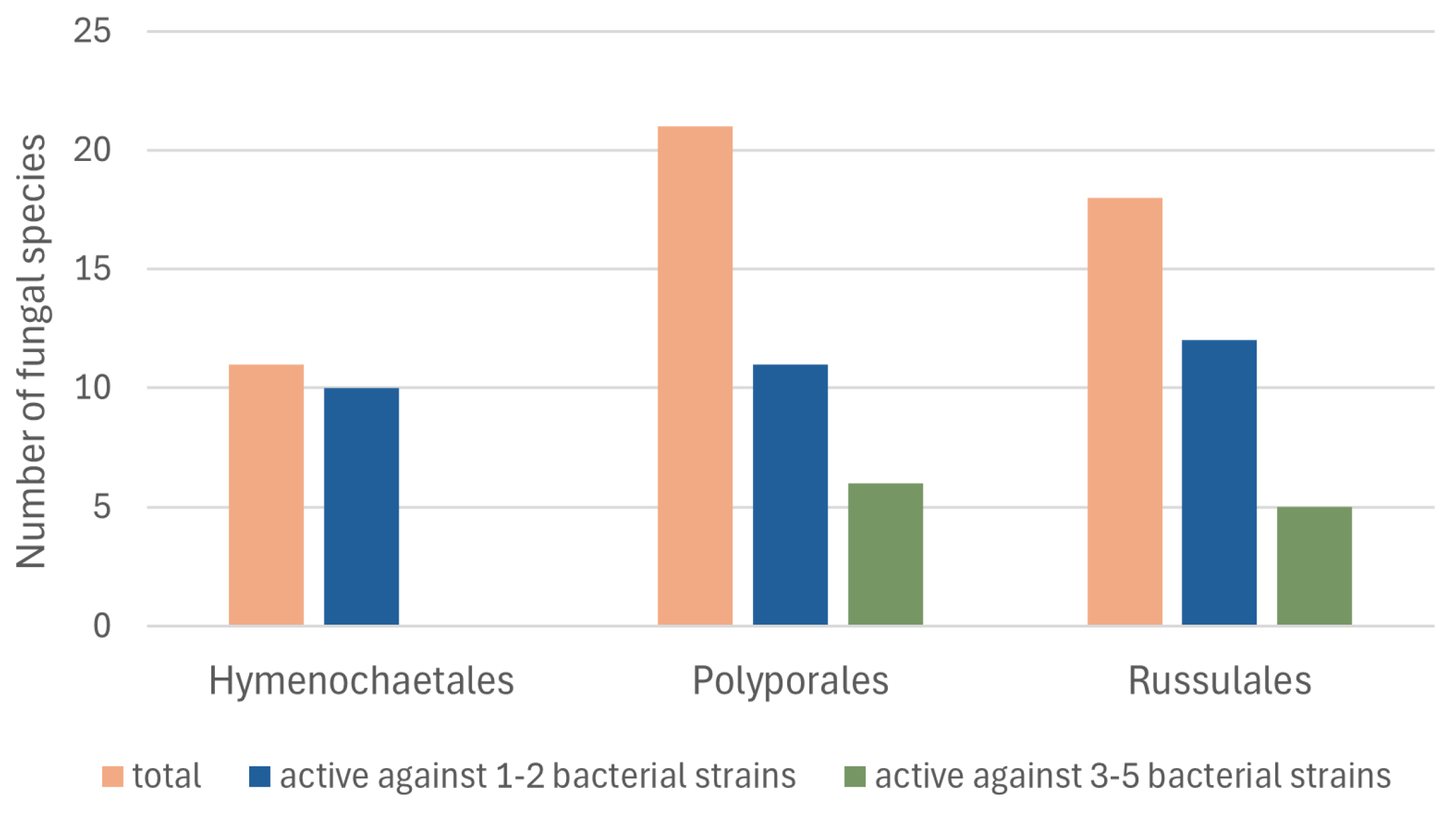

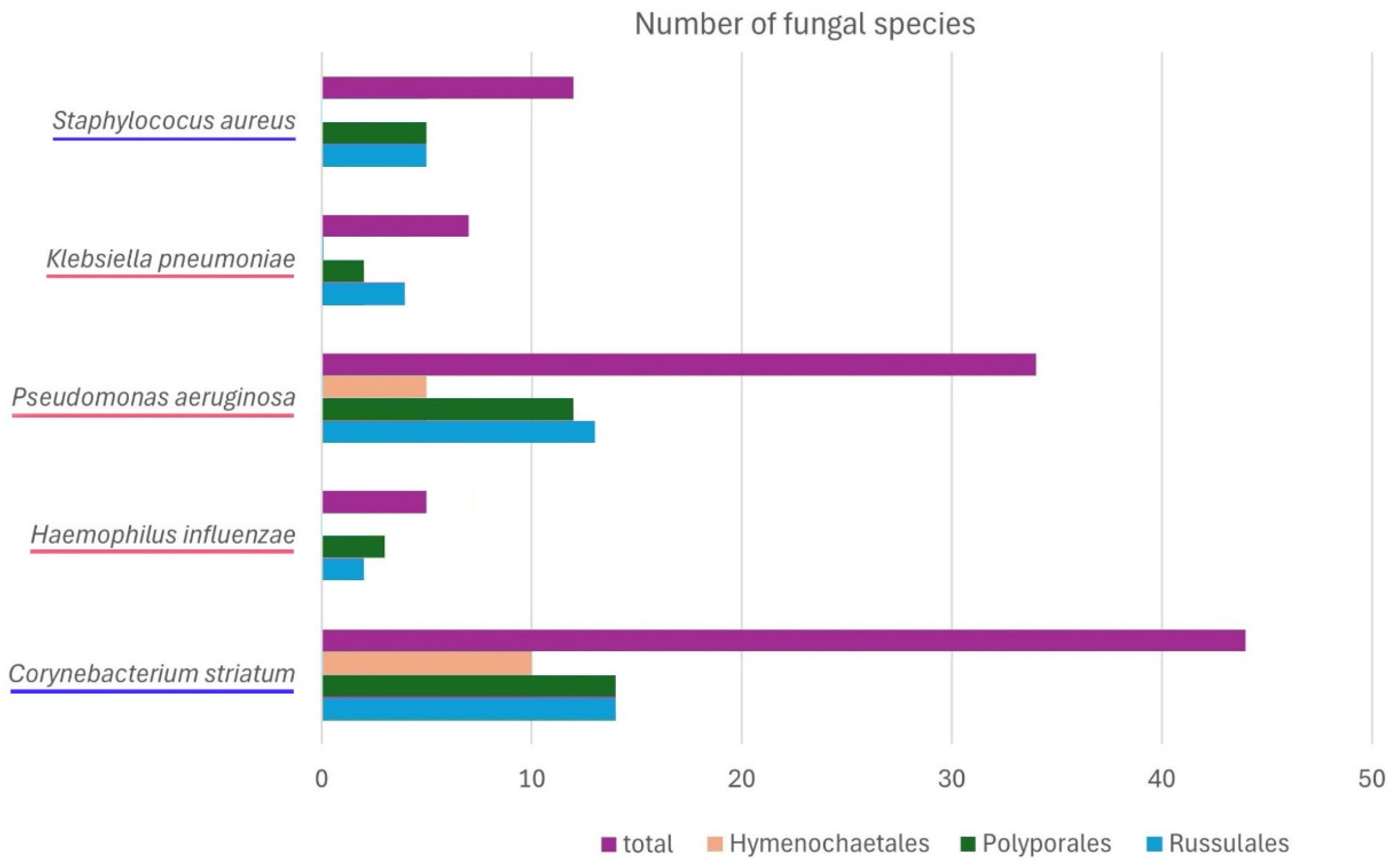

2. Results

3. Discussion

- (1)

- The fungal species that inhibited the growth of S. aureus both in our experiments and as mycelia growing in culture are the following: Baltazaria galactina, Byssomerulius corium, Chondrostereum purpureum, Laxitextum bicolor, Noblesia crocea, Peniophora cinerea, and Xylobolus frustulatus;

- (2)

- The fungal species that inhibited the growth of S. aureus as fruiting body extracts, but did not show such activity as mycelia in culture are the following: Phanerochaete sordida and Phlebiopsis gigantea.

- (3)

- The fungal species that were not active in their fruiting body extracts but were active as living mycelia are the following: Hydnoporia tabacina, Hymenochaete rubiginosa, Mycoacia livida, Peniophora incarnata, P. quercina, Stereum hirsutum, S. rugosum, and S. sanguinolentum.

- (1)

- The fungi that inhibited S. aureus as fruitbody extracts, but not as culture extracts are the following: Chondrostereum purpureum, Irpex lacteus, and Xylobolus frustulatus;

- (2)

- The fungi that were not active as fruitbody extracts, but were active as culture extracts are the following: Peniophora quercina and Stereum hirsutum.

- (1)

- Active both in our study and in the study [56]: Chondrostereum purpureum;

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Fungal Samples

4.2. Extract Preparation

4.3. Bacterial Strains and Testing the Antibacterial Activity

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Fungal Species | No. of Extract in the Fungi Extract Bank® | Collector(s) *, Month and Year of Collecting | Reference Herbarium Specimen No./Field Number | Area, Host |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agaricales | ||||

| Chondrostereum purpureum | 238 | KW, XI.2022 | Hajnówka vicinities, Pyrus domestica | |

| Ch. purpureum | 248 | EY, KW, XII.2022 | BLS M-3975/EYu 221229-1 | Hajnówka vicinities, Cerasus vulgaris |

| Radulomyces molaris | 239 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10053/EYu 230509-6 | BPF **, Salix caprea |

| Amylocorticiales | ||||

| Amylocorticium cebennense | 344 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-10832/EYu 230926-8 | BPF, Picea abies |

| Amylocorticium subincarnatum | 336 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-10840/EYu 230926-1a | BPF, Picea abies |

| Irpicodon pendulus | 346 | EY, MW, XI.2023 | BLS M-10831/EYu 231103-3 | BPF, Pinus sylvestris |

| Cantharellales | ||||

| Botryobasidium subcoronatum | 303 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10821/EYu 230525-3 | BPF, Pinus sylvestris |

| Coniophorales | ||||

| Coniophora arida | 345 | EY, XI.2023 | BLS M-10830/EYu 231103-2 | BPF, Picea abies |

| Gloeophyllales | ||||

| Boreostereum radiatum | 236 | MW, X.2022 | BLS M-3982 | Białystok vicinities, Picea abies |

| Hymenochaetales | ||||

| Hydnoporia tabacina | 78 | EY, KW, XII.2022 | BLS M-3974/EYu 221229-5 | Hajnówka vicinities, Corylus avellana |

| H. tabacina | 243 | MW, X.2018 | BLS M-603 | BPF, Salix cinerea |

| H. tabacina | 286 | EY, VI.2023 | BLS M-10046/EYu 230608-3 | BPF, Picea abies |

| Hymenochaete rubiginosa | 56 | MW, XI.2021 | BPF, Quercus robur | |

| Kneiffiella barba-jovis | 283 | EY, VI.2023 | BLS M-10064/EYu 230608-2 | BPF, Betula sp. |

| Lyomyces crustosus | 292-1 | EY, VI.2023 | BLS M-10311/EYu 230625-4 | BPF, Corylus avellana |

| L. crustosus | 292-2 | EY, VIII.2023 | BLS M-10323/EYu 230803-1 | BPF, Corylus avellana |

| Peniophorella praetermissa | 349 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-10842/EYu 230921-4 | BPF, Fraxinus excelsior |

| Resinicium bicolor | 276 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10054/EYu 230501-1 | BPF, Picea abies |

| R. bicolor | 308 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-11611/EYu 230907-2 | BPF, Pinus sylvestris |

| Skvortzovia furfuracea | 285 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10051/EYu 230509-4 | BPF, Pinus sylvestris |

| Xylodon brevisetus | 309 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-11612/EYu 230907-7 | BPF, Picea abies |

| Xylodon nesporii | 304 | EY, VII.2023 | BLS M-10321/EYu 230710-5 | BPF, Corylus avellana |

| Xylodon paradoxus | 265 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10050/EYu 230524-4 | BPF, Carpinus betulus |

| X. paradoxus | 284 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10048/EYu 230501-4 | BPF, Quercus robur |

| Xylodon spathulatus | 347 | EY, MW, IX.2023 | BLS M-10847/EYu 230919-6 | Łuków vicinities, Abies alba |

| Polyporales | ||||

| Byssomerulius corium | 245 | EY, X.2022 | BLS M-3939/EYu 221009-9 | BPF, Populus tremula |

| B. corium | 264 | EY, IV.2023 | BLS M-10063/EYu 230423-1 | BPF, Carpinus betulus |

| Crustoderma dryinum | 271 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10056/EYu 230511-1 | BPF, Picea abies |

| Dacryobolus karstenii | 348 | EY, MW, XI.2023 | BLS M-10829/EYu 231103-1 | BPF, Pinus sylvestris |

| Etheirodon fimbriatum | 333 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-10838/EYu 230926-2 | BPF, Alnus glutinosa |

| E. fimbriatum | 341 | EY, X.2023 | BLS M-10824/EYu 231008-4 | BPF, Salix caprea |

| Hyphoderma transiens | 343 | EY X.2023 | BLS M-10826/EYu 231008-6 | BPF, Tilia cordata |

| Hyphoderma setigerum | 222-1 | EY, X.2022 | BLS M-3944/EYu 221016-1 | BPF, Betula pendula |

| H. setigerum | 222-2 | EY, III.2022 | BLS M-3931/EYu 220320-1 | BPF, Betula pendula |

| Irpex lacteus | 311 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-10856/EYu 230907-6 | BPF, Sorbus aucuparia |

| Meruliopsis taxicola | 273 | EY, MW, V.2023 | BLS M-10060/EYu 230525-2 | BPF, Pinus sylvestris |

| Merulius tremellosus | 170 | MW, XI.2019 | BPF, Populus tremula | |

| Mutatoderma mutatum | 244 | EY, X.2022 | BLS M-3943/EYu 221009-8 | BPF, Populus tremula |

| Mycoacia livida | 335 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-10843/EYu 230921-3 | BPF, Fraxinus excelsior |

| Noblesia crocea (without substratum) | 302-1 | MW, VIII.2023 | BLS M-10309/230815-1a | Hajnówka vicinities, Malus domestica |

| N. crocea (the part of basidiomata interspersed with substratum particles) | 302-2 | MW, VIII.2023 | BLS M-10309/230815-1b | the same as above |

| Phanerochaete sordida | 291 | EY, VI.2023 | BLS M-10314/EYu 230625-5 | BPF, Fraxinus excelsior |

| Ph. sordida | 305 | EY, VII.2023 | BLS M-10322/EYu 230710-4 | BPF, Populus tremula |

| Phanerochaete velutina | 334 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-10844/EYu 230921-2 | BPF, Fraxinus excelsior |

| Phlebia centrifuga | 202-1 | GK, VIII.2020 | BPF, Picea abies | |

| Ph. centrifuga | 202-2 | EY, X.2023 | BLS M-3956/EYu 221016-7 | BPF, Picea abies |

| Phlebia rufa | 229 | EY, VIII.2022 | BLS M-3565/EYu 220802-12 | BPF, Corylus avellana |

| Ph. rufa | 232 | EY, V.2022 | BLS M-11610/EYu 230501-52 | BPF, Fraxinus excelsior |

| Phlebiodontia cf. subochracea | 313 | EY, MW, IX.2023 | BLS M-10846/EYu 230919-7 | Łuków vicinities, Abies alba |

| Phlebiopsis gigantea | 247-1 | EY, KW, XII.2022 | BLS M-3977/EYu 221229-4 | Hajnówka vicinities, Pinus sylvestris |

| Ph. gigantea | 247-2 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10059/EYu 230501-8 | BPF, Pinus sylvestris |

| Scopuloides hydnoides | 338 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-10835/EYu 230926-5 | BPF, Fraxinus excelsior |

| Steccherinum bourdotii | 339 | EY, MW, IX.2023 | BLS M-10850/EYu 230919-1 | Łuków vicinities, Acer pseudoplatanus |

| Steccherinum ochraceum | 296 | EY, VII.2023 | BLS M-10315/EYu 230702-2a | BPF, Carpinus betulus |

| S. ochraceum | 340 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-10837/EYu 230926-3 | BPF, Alnus glutinosa |

| Russulales | ||||

| Asterostroma medium | 312 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-10845/EYu 230919-8 | Łuków vicinities, Abies alba |

| Baltazaria galactina | 231 | EY, VIII.2022 | BLS M-3563/EYu 220802-4 | BPF, Populus tremula |

| B. galactina | 233 | MW, IX.2022 | BLS M-3981 | BPF, Tilia cordata |

| Dentipellis fragilis | 342 | MW, X.2023 | BLS M-10828 | BPF, Alnus glutinosa |

| Gloiothele lactescens | 314 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-10841/EYu230921-5 | BPF, cf. Fraxinus excelsior |

| Laxitextum bicolor | 178 | MW, IX.2020 | BLS M-3630 | BPF, Salix caprea |

| L. bicolor | 235 | MW, X.2022 | BLS M-3996 | Białystok vicinities, Salix caprea |

| Peniophora cinerea | 293 | EY, VI.2023 | BLS M-10325/EYu 230625-2 | BPF, Alnus glutinosa |

| P. cinerea | 295 | EY, VII.2023 | BLS M-10316/EYu 230710-3 | BPF, Corylus avellana |

| P. cinerea | 310 | EY, IX.2023 | BLS M-10857/EYu 230907-4 | BPF, Sorbus aucuparia |

| Peniophora incarnata | 272 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10062/EYu 230501-5 | BPF, Populus tremula |

| Peniophora laeta | 288-1 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10052/EYu 230509-7 | BPF, Carpinus betulus |

| P. laeta | 288-2 | EY, VIII.2023 | BLS M-10324/EYu 230803-2 | BPF, Carpinus betulus |

| Peniophora limitata | 290 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10327/EYu 230509-8 | BPF, Fraxinus excelsior |

| Peniophora pithya | 287 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10047/EYu 230509-2 | BPF, Picea abies |

| Peniophora quercina | 237 | EY, X.2022 | BLS M-3957/EYu 221016-9 | BPF, Quercus robur |

| Peniophora rufomarginata | 249-1 | MW, XII.2022 | BLS M-10070 | BPF, Tilia cordata |

| P. rufomarginata | 249-2 | EY, X.2022 | BLS M-3938/EYu 221009-10 | BPF, Tilia cordata |

| Scytinostroma odoratum | 337 | EY, MW, IX.2023 | BLS M-10849/EYu 230919-3 | Łuków vicinities, Pinus sylvestris |

| Stereum hirsutum | 167 | MW, XII.2020 | BPF, Carpinus betulus | |

| S. hirsutum | 289 | EY, VI.2023 | BLS M-10317/EYu 230625-2 | BPF, Alnus glutinosa |

| S. hirsutum | 294-1 | EY, VII.2023 | BLS M-10308/EYu 230710-1 | BPF, Quercus robur |

| S. hirsutum | 294-2 | EY, VIII.2023 | BLS M-10320/EYu 230803-3 | BPF, Quercus robur |

| Stereum rugosum | 79 | EY, IV.2023 | BLS M-10061/EYu 230423-4 | BPF, Corylus avellana |

| S. rugosum | 281 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10065/EYu 230501-3 | BPF, Quercus robur |

| Stereum sanguinolentum | 274 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10055/EYu 230509-1 | BPF, Picea abies |

| S. sanguinolentum | 275 | EY, V.2023 | BLS M-10058/EYu 230511-6 | BPF, Pinus sylvestris |

| Stereum subtomentosum | 197 | MW, X.2019 | BLS M-1946 | BPF, Alnus glutinosa |

| Xylobolus frustulatus | 186-1 | GK, VI.2021 | BPF, Quercus robur | |

| X. frustulatus | 186-2 | EY, IV.2023 | BLS M-10069/EYu 230423-3 | BPF, Quercus robur |

References

- Bernardy, E.E.; Petit, R.A., 3rd; Raghuram, V.; Alexander, A.M.; Read, T.D.; Goldberg, J.B. Genotypic and phenotypic diversity of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from cystic fibrosis patient lung infections and their interactions with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 2020, 11, e00735-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cigana, C.; Bianconi, I.; Baldan, R.; De Simone, M.; Riva, C.; Sipione, B.; Rossi, G.; Cirillo, D.M.; Bragonzi, A. Staphylococcus aureus impacts Pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic respiratory disease in murine models. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 217, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciofu, O.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Tolerance and resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms to antimicrobial agents—How P. aeruginosa can escape antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.Y.K.; Nang, S.C.; Chan, H.-K.; Li, J. Novel antimicrobial agents for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 187, 114378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welp, A.L.; Bomberger, J.M. Bacterial community interactions during chronic respiratory disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, S.A.; Ahn, D.; Prince, A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae adaptation to innate immune clearance mechanisms in the lung. J. Innate Immun. 2018, 10, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, T.M.R.; da Silva, A.B.M.F.; Morais, A.L.F.; de Oliveira, J.F. Bacterial resistance: A narrative review on Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Res. Soc. Dev. 2023, 12, e25121143640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamkin, E.; Lorenz, B.P.; McCarty, A.; Fulte, S.; Eisenmesser, E.; Horswill, A.R.; Clark, S.E. Airway Corynebacterium interfere with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus infection and express secreted factors selectively targeting each pathogen. Infect. Immun. 2025, 93, e0044524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limoli, D.H.; Hoffman, L.R. Help, hinder, hide and harm: What can we learn from the interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus during respiratory infections? Thorax 2019, 74, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Lodha, R.; Kabra, S.K. Upper respiratory tract infections. Indian J. Pediatr. 2001, 68, 1135–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.Y.C.; Bae, J.S.; Otto, M. Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence 2021, 12, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, D.; Sharma, L.; Dela Cruz, C.S.; Zhang, D. Clinical epidemiology, risk factors, and control strategies of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 750662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudet, A.; Regad, M.; Gibot, S.; Conrath, É.; Lizon, J.; Demoré, B.; Florentin, A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in patients with severe COVID-19 in intensive care units: A retrospective study. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abavisani, M.; Keikha, M.; Karbalaei, M. First global report about the prevalence of multi-drug resistant Haemophilus influenzae: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariff, M.; Aditi, A.; Beri, k. Corynebacterium striatum: An emerging respiratory pathogen. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2018, 12, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, A.; Campanella, E.; Stracquadanio, S.; Ceccarelli, M.; Zagami, A.; Nunnari, G.; Cacopardo, B. Corynebacterium striatum bacteremia during SARS-CoV2 infection: Case report, literature review, and clinical considerations. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2022, 14, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair, R.J.; Tor, J. Antibiotics and bacterial resistance in the 21st century. Perspect. Med. Chem. 2014, 6, 25–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S.; Kaistha, S.; Das, A.J.; Kumar, R. Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria: A Challenge to Modern Medicine; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, N.A.; McKillip, J.L. Antibiotic resistance crisis: Challenges and imperatives. Biologia 2021, 76, 1535–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwobodo, D.C.; Ugwu, M.C.; Anie, C.O.; Al-Ouqaili, M.T.S.; Ikem, J.C.; Chigozie, U.V.; Saki, M. Antibiotic resistance: The challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwehl, S.; Stadler, M. Exploitation of fungal biodiversity for discovery of novel antibiotics. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016, 398, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysakova, V.; Krasnopolskaya, L.; Yarina, M.; Ziangirova, M. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of metabolites from basidiomycetes: A review. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yacouba, A.; Olowo-okere, A.; Yunusa, I. Repurposing of antibiotics for clinical management of COVID-19: A narrative review. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2021, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, B.; Ilaghi, M.; Shahsavani, Y.; Faramarzpour, M.; Oghazian, M.B.; Rahimi, H.-R. Antibiotics with antiviral and anti-inflammatory potential against COVID-19: A review. Curr. Rev. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. 2023, 18, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, K.-H.; Ryvarden, L. Corticioid fungi of Europe. Vol. 1. Acanthobasidium—Gyrodontium; Fungiflora: Oslo, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, K.-H. Re-thinking the classification of Corticioid fungi. Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 1040–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Noorabadi, M.T.; Thiyagaraja, V.; He, M.Q.; Johnston, P.R.; Wijesinghe, S.N.; Armand, A.; Biketova, A.Y.; Chethana, K.W.T.; Erdoğdu, M.; et al. The 2024 Outline of Fungi and fungus-like taxa. Mycosphere 2024, 15, 5146–6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, W.; van der Wal, A. Interaction between saprotrophic basidiomycetes and bacteria. Br. Mycol. Soc. Symp. Ser. 2008, 28, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Terhonen, E.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Kasanen, R.; Asiegbu, F.O. The impacts of treatment with biocontrol fungus (Phlebiopsis gigantea) on bacterial diversity in Norway spruce stumps. Biol. Control 2013, 64, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folman, L.B.; Paulien, J.A.; Gunnewiek, K.; Boddy, L.; de Boer, W. Impact of white-rot fungi on numbers and community composition of bacteria colonizing beech wood from forest soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 63, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatley, N.G.; Jennings, M.A.; Florey, H.W. Antibiotics from Stereum hirsutum. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1947, 28, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mellows, G.; Mantle, P.G.; Feline, T.C.; Williams, D.J. Sesquiterpenoid metabolites from Stereum complicatum. Phytochemistry 1973, 12, 2717–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.S.R.; Anchel, M. Frustulosinol, an antibiotic metabolite of Stereum frustulosum: Revised structure of frustulosin. Phytochemistry 1977, 16, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quack, W.; Anke, T.; Oberwinkler, F.; Giannetti, B.M.; Steglich, W. Antibiotics from basidiomycetes. V. Merulidial, a new antibiotic from the basidiomycete Merulius tremellosus Fr. J. Antibiot. 1978, 31, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupka, J.; Anke, T.; Mizumoto, K.; Giannetti, B.M.; Steglich, W. Antibiotics from basidiomycetes. XVII. The effect of marasmic acid on nucleic acid metabolism. J. Antibiot. 1983, 36, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anke, H.; Sterner, O.; Steglich, W. Structure-activity relationships for unsaturated dialdehydes. 3. Mutagenic, antimicrobial, cytotoxic, and phytotoxic activities of merulidial derivatives. J. Antibiot. 1989, 42, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, L.S.; Ki, D.-W.; Kim, J.-Y.; Choi, D.-C.; Lee, I.-K.; Yun, B.-S. Dentipellin, a new antibiotic from culture broth of Dentipellis fragilis. J. Antibiot. 2021, 74, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, W.H.; Harris, G.C.M. Investigation into the production of bacteriostatic substances by fungi. VI. Examination of the larger Basidiomycetes. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1944, 31, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieson, J. Antibiotics from Victorian Basidiomycetes. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 1946, 24, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, W.H. Investigation into the production of bacteriostatic substances by fungi. Preliminary examination of more of the larger Basidiomycetes and some of the larger Ascomycetes. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1946, 33, 188–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, B.M.; Steglich, W.; Quack, W.; Anke, T.; Oberwinkler, F. Antibiotika aus Basidiomyceten, VI. Merulinsäuren A, B und C, neue Antibiotika aus Merulius tremellosus Fr. und Phlebia radiata Fr. Z. Naturforsch. C 1978, 33, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zjawiony, J.K.; Jin, W.; Vilgalys, R. Merulius incarnatus Schwein., a rare mushroom with highly selective antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2005, 7, 365–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cateni, F.; Doljak, B.; Zacchigna, M.; Anderluh, M.; Piltaver, A.; Scialinoe, G.; Banfie, E. New biologically active epidioxysterols from Stereum hirsutum. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 6330–6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Silva, V.; Gusmão, N.B.; Gibertoni, T.B. Antibacterial activity of ethyl acetate extract of Agaricomycetes collected in Northeast Brazil. Curr. Res. Environ. Appl. Mycol. 2017, 7, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tamrakar, S.; Nishida, M.; Amen, Y.; Tran, H.B.; Suhara, H.; Fukami, K.; Parajuli, G.P.; Shimizu, K. Antibacterial activity of Nepalese wild mushrooms against Staphylococcus aureus and Propionibacterium acnes. J. Wood Sci. 2017, 63, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevindik, M.; Ozdemir, B.; Bal, C.; Selamoglu, Z. Bioactivity of EtOH and MeOH extracts of basidiomycetes mushroom (Stereum hirsutum) on atherosclerosis. Arch. Razi Inst. 2021, 76, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- İnci, Ş.; Sevindik, M.; Kırbağ, S.; Akgül, H. Antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal activity of Hymenochaete rubiginosa. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 2022, 13, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, W.J.; Hervey, A.; Davidson, R.W.; Ma, R.; Robbins, W.C. A survey of some wood-destroying and other fungi for antibacterial activity. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 1945, 72, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, W.H. Investigation into the production of bacteriostatic substances by fungi. Preliminary examination of the fifth 100 species, all basidiomycetes, mostly of the wood-destroying type. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1946, 27, 140–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hervey, A.H. A survey of 500 basidiomycetes for antibacterial activity. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 1947, 74, 476–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, W.H. Investigation into the production of bacteriostatic substances by fungi. Preliminary examination of the sixth 100 species, more basidiomycetes of the wood-destroying type. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1947, 28, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, W.H. Investigation into the production of bacteriostatic substances by fungi. Preliminary examination of the seventh 100 species, all basidiomycetes. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1947, 28, 247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Thorn, R.G.; Tsuneda, A. Interactions between various wood-decay fungi and bacteria: Antibiosis, attack, lysis or inhibition. Rept. Tottori Mycol. Inst. 1992, 30, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, A.B.J.; Cadelis, M.M.; Diao, Y.; Park, D.; Lumley, T.; Weir, B.S.; Copp, B.R.; Wiles, S. Screening of fungi for antimycobacterial activity using a medium-throughput bioluminescence-based assay. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 739995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, S.; Natori, S. Some observations on antibacterial activity of wood-rotting fungi. J. Pharm. Soc. Jpn. 1952, 72, 594–595. [Google Scholar]

- Suay, I.; Arenal, F.; Asensio, F.J.; Basilio, A.; Cabello, M.A.; Díez, M.T.; García, J.B.; del Val, A.G.; Gorrochategui, J.; Hernández, P.; et al. Screening of basidiomycetes for antimicrobial activities. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2000, 78, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L.H.; Machado, K.M.G.; Jacob, C.C.; Capelari, M.; Rosa, C.A.; Zani, C.L. Screening of Brazilian basidiomycetes for antimicrobial activity. Mem. I. Oswaldo Cruz 2003, 98, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrimec, M.B.; Zrimec, A.; Slanc, P.; Kac, J.; Kreft, S. Screening for antibacterial activity in 72 species of wood-colonizing fungi by the Vibrio fisheri bioluminescence method. J. Basic Microbiol. 2004, 44, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, M.; Naumann, A.; Ferrero, F.; Malowd, M. Exothermic processes in industrial-scale piles of chipped pine-wood are linked to shifts in gamma-, alphaproteobacterial and fungal ascomycete communities. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2010, 64, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tláskal, V.; Zrůstová, P.; Vrška, T.; Baldrian, P. Bacteria associated with decomposing dead wood in a natural temperate forest. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fix157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaj, A.; Lee, T.S.; Ohga, S. Molecular analysis of ITS region and antibacterial activities of Stereum hirsutum. J. Fac. Agric. Kyushu Univ. 2011, 56, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quereshi, S.; Pandey, A.K.; Sandhu, S.S. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of different Ganoderma lucidum extracts. People’s J. Sci. Res. 2010, 3, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.; Weise, A.; Niclas, H.-J. The solvent dimethyl sulfoxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 1967, 6, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwani, T.; Desai, K.; Patel, D.; Lawani, D.; Bahaley, P.; Joshi, P.; Kothari, V. Effect of various solvents on bacterial growth in context of determining MIC of various antimicrobials. Internet J. Microbiol. 2008, 7, 1–6. Available online: https://ispub.com/ijmb/7/1/5909# (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Camp, J.E.; Nyamini, S.B.; Scott, F.J. Cyrene™ is a green alternative to DMSO as a solvent for antibacterial drug discovery against ESKAPE pathogens. RSC Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašeta, M.; Mišković, J.; Čapelja, E.; Zapora, E.; Fabijan, A.P.; Knežević, P.; Karaman, M. Do Ganoderma species represent novel sources of phenolic based antimicrobial agents? Molecules 2023, 28, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| O * | Fungal Species ** | No. of Extract in the Fungi Extract Bank® | Inhibitory Effect of Fungal Extracts (Minimum Bactericidal Concentration, mg/mL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Haemophilus influenzae | Corynebacterium striatum | |||

| Ag | Chondrostereum purpureum (Pers.) Pouzar | 238 | 25 | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| Ag | Ch. purpureum | 248 | – | – | 25 | – | – |

| Ag | Radulomyces molaris (Chaillet ex Fr.) M.P. Christ. | 239 | – | – | 25 | – | – |

| Am | Amylocorticium cebennense (Bourdot) Pouzar | 344 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Am | A. subincarnatum (Peck) Pouzar | 336 | 25 | 25 | 50 | – | 50 |

| Am | Irpicodon pendulus (Alb. & Schwein.) Pouzar | 346 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| Ca | Botryobasidium subcoronatum (Höhn. & Litsch.) Donk | 303 | – | – | – | – | 25 |

| Co | Coniophora arida (Fr.) P. Karst. | 345 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| G | Boreostereum radiatum (Peck) Parmasto | 236 | – | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| H | Hydnoporia tabacina (Sowerby) Spirin, Miettinen & K.H. Larss. | 78 | – | – | 50 | – | 50 |

| H | H. tabacina | 243 | – | – | – | – | – |

| H | H. tabacina | 286 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| H | Hymenochaete rubiginosa (J.F. Gmel.) Lév. | 56 | – | – | 50 | – | 50 |

| H | Kneiffiella barba-jovis (Bull.) P. Karst. | 283 | – | – | – | – | 25 |

| H | Lyomyces crustosus (Pers.) P. Karst. | 292-1 | – | – | – | – | 25 |

| H | L. crustosus | 292-2 | – | – | – | – | 25 |

| H | Peniophorella praetermissa (P. Karst.) K.H. Larss. | 349 | – | – | – | – | – |

| H | Resinicium bicolor (Alb. & Schwein.) Parmasto | 276 | – | – | – | – | – |

| H | R. bicolor | 308 | – | – | 50 | – | 50 |

| H | Skvortzovia furfuracea (Bres.) G. Gruhn & Hallenberg | 285 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| H | Xylodon brevisetus (P. Karst.) Hjortstam & Ryvarden | 309 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| H | Xylodon nesporii (Bres.) Hjortstam & Ryvarden | 304 | – | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| H | Xylodon paradoxus (Schrad.) Chevall. | 265 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| H | X. paradoxus | 284 | – | – | – | – | 25 |

| H | Xylodon spathulatus (Schrad.) Kuntze | 347 | – | – | 50 | – | 50 |

| P | Byssomerulius corium (Pers.) Parmasto | 245 | – | – | – | – | – |

| P | B. corium | 264 | 25 | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| P | Crustoderma dryinum (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Parmasto | 271 | – | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| P | Dacryobolus karstenii (Bres.) Oberw. ex Parmasto | 348 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| P | Etheirodon fimbriatum (Pers.) Banker | 333 | – | – | – | – | – |

| P | E. fimbriatum | 341 | – | – | – | – | – |

| P | Hyphoderma transiens (Bres.) Parmasto | 343 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| P | Hyphoderma setigerum (Fr.) Donk | 222-1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| P | H. setigerum | 222-2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| P | Irpex lacteus (Fr.) Fr. | 311 | 25 | – | 50 | – | 50 |

| P | Meruliopsis taxicola (Pers.) Bondartsev | 273 | – | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| P | Merulius tremellosus Fr. | 170 | – | – | 25 | – | – |

| P | Mutatoderma mutatum (Peck) C.E. Gómez | 244 | – | – | – | – | – |

| P | Mycoacia livida (Pers.) Zmitr. | 335 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| P | Noblesia crocea (Schwein.) Nakasone | 302-1 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| P | N. crocea | 302-2 | 25 | – | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| P | Phanerochaete sordida (P. Karst.) J. Erikss. & Ryvarden | 291 | 25 | 25 | 25 | – | 25 |

| P | Ph. sordida | 305 | – | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| P | Phanerochaete velutina (DC.) P. Karst. | 334 | – | – | – | – | 25 |

| P | Phlebia centrifuga P. Karst. | 202-1 | – | – | 50 | 25 | 25 |

| P | Ph. centrifuga | 202-2 | – | – | 25 | 50 | 25 |

| P | Phlebia rufa (Pers.) M.P. Christ. | 229 | – | – | 50 | 50 | – |

| P | Ph. rufa | 232 | – | – | – | – | – |

| P | Phlebiodontia cf. subochracea (Bres.) Motato-Vásq. & Gugliotta | 313 | – | – | – | – | – |

| P | Phlebiopsis gigantea (Fr.) Jülich | 247-1 | 25 | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| P | Ph. gigantea | 247-2 | – | – | 25 | – | – |

| P | Scopuloides hydnoides (Cooke & Massee) Hjortstam & Ryvarden | 338 | – | – | 50 | – | – |

| P | Steccherinum bourdotii Saliba & A. David | 339 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| P | Steccherinum ochraceum (Pers. ex J.F. Gmel.) Gray | 296 | – | – | – | – | 25 |

| P | S. ochraceum | 340 | – | – | 50 | – | 50 |

| R | Asterostroma medium Bres. | 312 | – | – | – | – | – |

| R | Baltazaria galactina (Fr.) Leal-Dutra, Dentinger & G.W. Griff. | 231 | – | – | – | – | – |

| R | B. galactina | 233 | 25 | – | 50 | – | – |

| R | Dentipellis fragilis (Pers.) Donk | 342 | – | – | 50 | – | – |

| R | Gloiothele lactescens (Berk.) Hjortstam | 314 | – | – | 25 | – | – |

| R | Laxitextum bicolor (Pers.) Lentz | 178 | – | – | 50 | – | 25 |

| R | L. bicolor | 235 | 25 | 25 | 25 | – | 25 |

| R | Peniophora cinerea (Pers.) Cooke | 293 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| R | P. cinerea | 295 | 25 | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| R | P. cinerea | 310 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| R | Peniophora incarnata (Pers.) P. Karst. | 272 | – | – | 50 | – | 25 |

| R | Peniophora laeta (Fr.) Donk | 288-1 | – | 25 | 25 | – | 25 |

| R | P. laeta | 288-2 | – | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| R | Peniophora limitata (Chaillet ex Fr.) Cooke | 290 | – | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| R | Peniophora pithya (Pers.) J. Erikss. | 287 | – | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| R | Peniophora quercina (Pers.) Cooke | 237 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| R | Peniophora rufomarginata (Pers.) Bourdot & Galzin | 249-1 | – | 50 | 25 | – | – |

| R | P. rufomarginata | 249-2 | 25 | – | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| R | Scytinostroma odoratum (Fr.) Donk | 337 | – | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| R | Stereum hirsutum (Willd.) Pers. | 289 | – | – | – | – | 25 |

| R | S. hirsutum | 294-1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| R | S. hirsutum | 294-2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| R | S. hirsutum | 167 | – | – | – | – | – |

| R | Stereum rugosum Pers. | 79 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| R | S. rugosum | 281 | – | – | – | – | – |

| R | Stereum sanguinolentum (Alb. & Schwein.) Fr. | 274 | – | – | 25 | – | 25 |

| R | S. sanguinolentum | 275 | – | – | – | – | 50 |

| R | Stereum subtomentosum Pouzar | 197 | – | – | – | – | 25 |

| R | Xylobolus frustulatus (Pers.) Boidin | 186-1 | 25 | 50 | 25 | – | 25 |

| R | X. frustulatus | 186-2 | 25 | – | – | – | 25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yurchenko, E.; Krasowska, M.; Kowczyk-Sadowy, M.; Zapora, E. Investigation of the Possible Antibacterial Effects of Corticioid Fungi Against Different Bacterial Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26073292

Yurchenko E, Krasowska M, Kowczyk-Sadowy M, Zapora E. Investigation of the Possible Antibacterial Effects of Corticioid Fungi Against Different Bacterial Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(7):3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26073292

Chicago/Turabian StyleYurchenko, Eugene, Małgorzata Krasowska, Małgorzata Kowczyk-Sadowy, and Ewa Zapora. 2025. "Investigation of the Possible Antibacterial Effects of Corticioid Fungi Against Different Bacterial Species" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 7: 3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26073292

APA StyleYurchenko, E., Krasowska, M., Kowczyk-Sadowy, M., & Zapora, E. (2025). Investigation of the Possible Antibacterial Effects of Corticioid Fungi Against Different Bacterial Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(7), 3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26073292