MSK1 Downstream Signaling Contributes to Inflammatory Pain in the Superficial Spinal Dorsal Horn

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

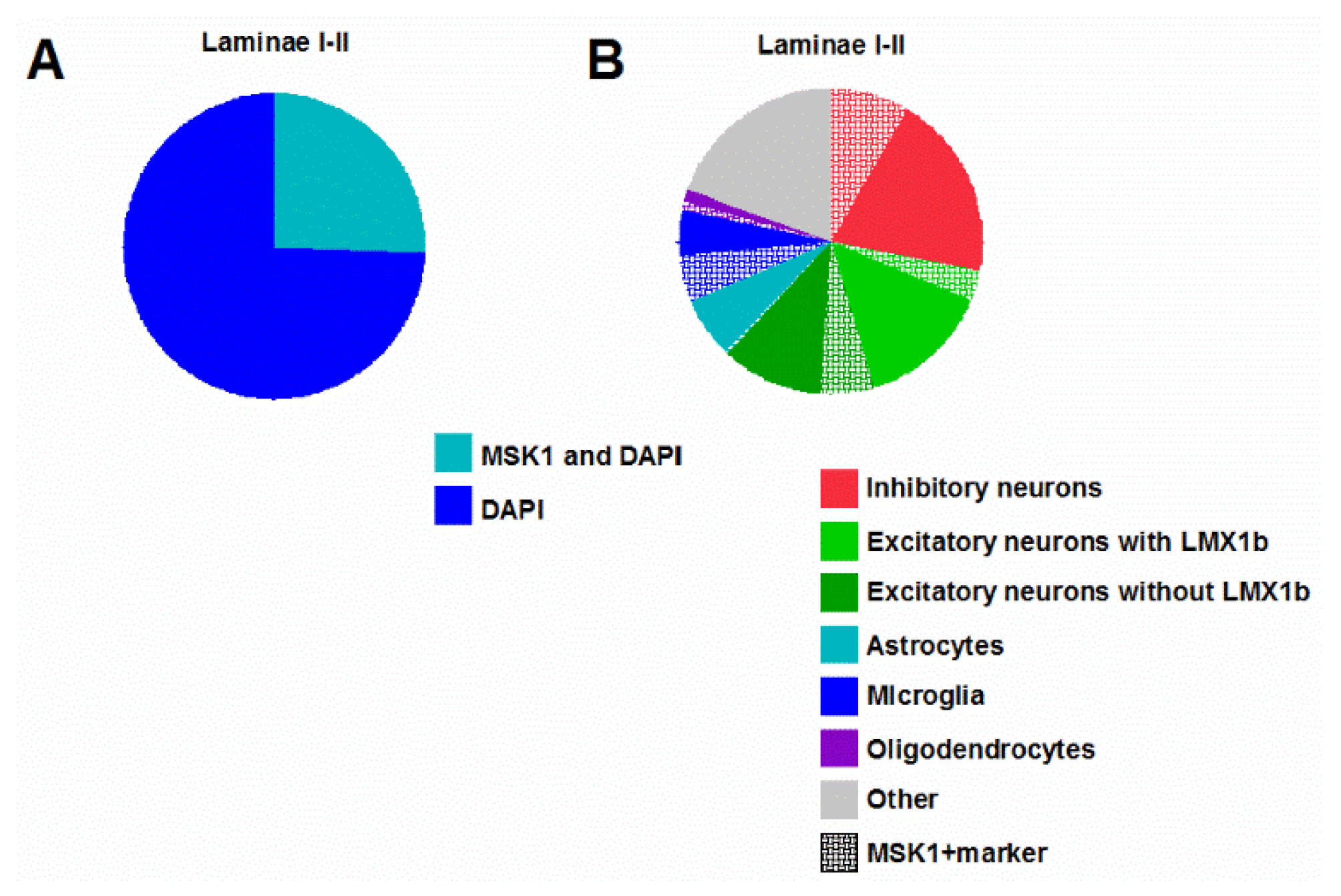

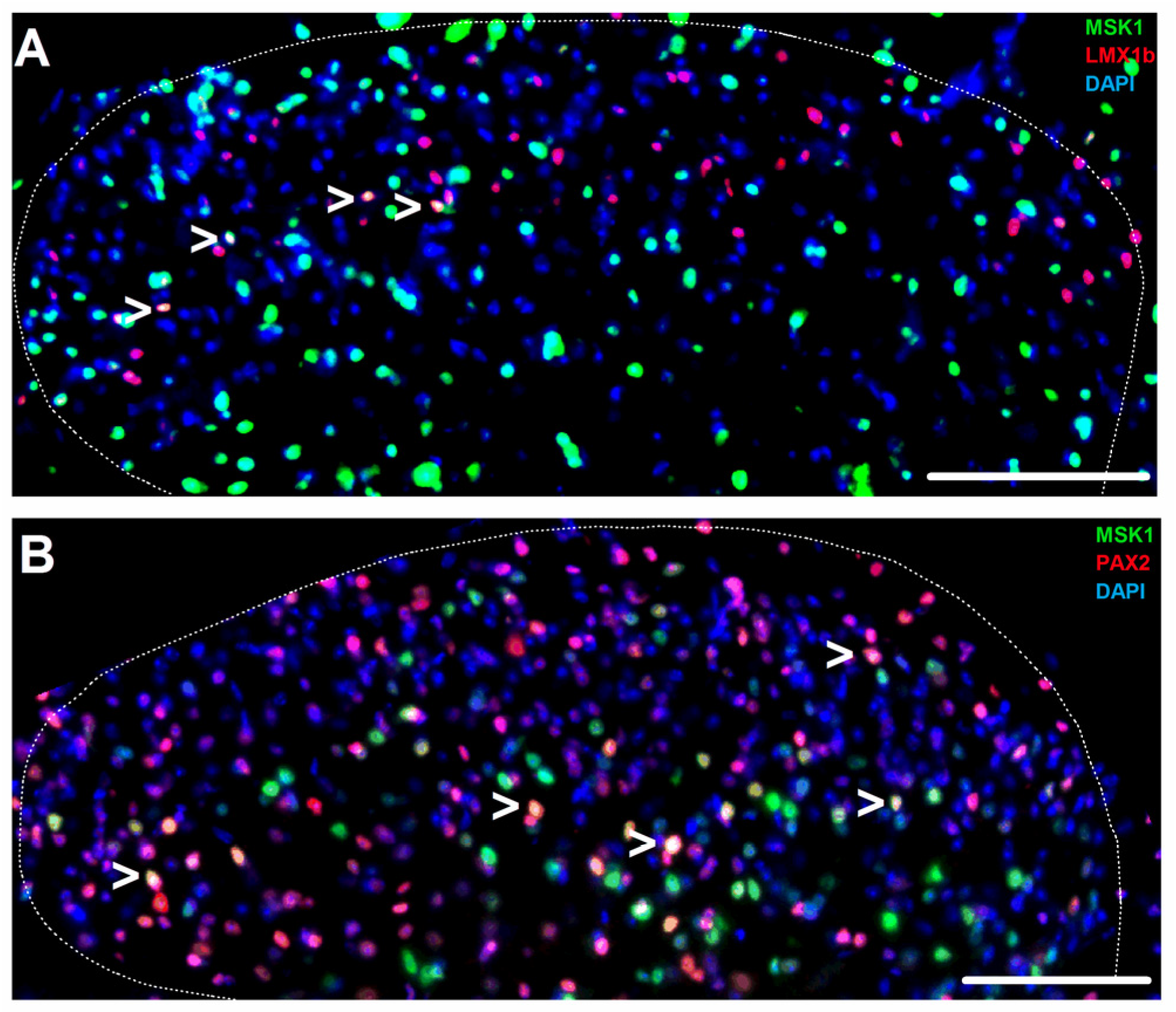

2.1. MSK1 Expression in SSDH Neuron, Microglia and Oligodendrocyte Sub-Populations

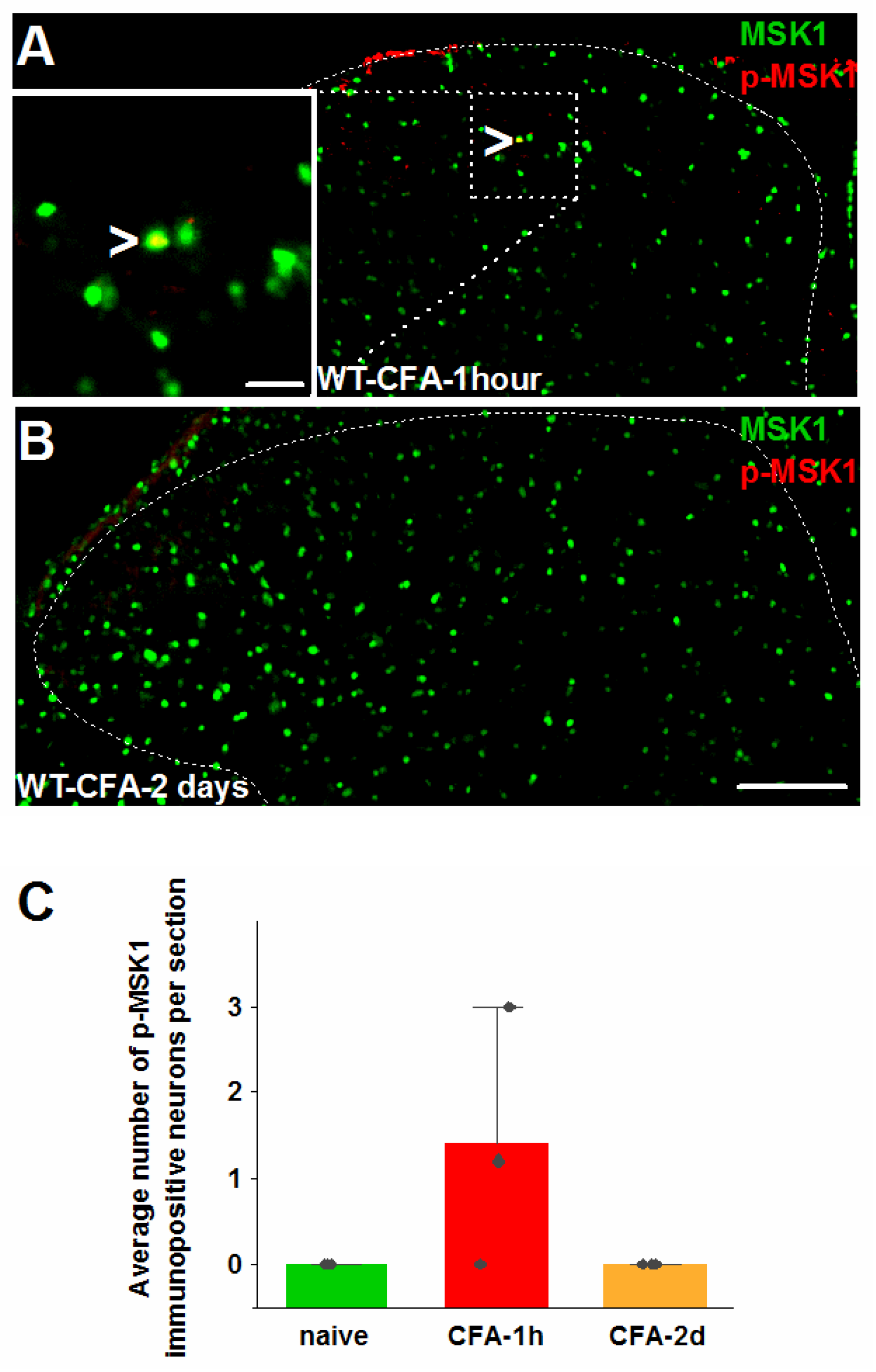

2.2. MSK1-Dependent Signaling in SSDH by Peripheral Inflammation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Inflammatory Model and Tissue Harvesting

4.3. Behavioral Testing

4.4. Immunostaining

4.5. Imaging and Quantification

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baral, P.; Udit, S.; Chiu, I.M. Pain and immunity: Implications for host defence. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costigan, M.; Scholz, J.; Woolf, C.J. Neuropathic pain: A maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 32, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latremoliere, A.; Woolf, C.J. Central sensitization: A generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J. Pain 2009, 10, 895–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Perez, J.V.; Irfan, J.; Febrianto, M.R.; Di Giovanni, S.; Nagy, I. Histone post-translational modifications as potential therapeutic targets for pain management. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 42, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Hakim, S.; Woolf, C.J. Immune drivers of physiological and pathological pain. J. Exp. Med. 2024, 221, e20221687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, C.J.; Costigan, M. Transcriptional and posttranslational plasticity and the generation of inflammatory pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 7723–7730. [Google Scholar]

- Moens, U.; Kostenko, S.; Sveinbjørnsson, B. The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinases (MAPKAPKs) in inflammation. Genes 2013, 4, 101–133. [Google Scholar]

- Reyskens, K.M.; Arthur, J.S.C. Emerging roles of the mitogen and stress activated kinases MSK1 and MSK2. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Mora, E.; González-Romero, D.; Meireles-da-Silva, M.; Sanz-Ezquerro, J.J.; Cuenda, A. p38δ controls Mitogen-and Stress-activated Kinase-1 (MSK1) function in response to toll-like receptor activation in macrophages. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1083033. [Google Scholar]

- Sattarifard, H.; Safaei, A.; Khazeeva, E.; Rastegar, M.; Davie, J.R. Mitogen-and stress-activated protein kinase (MSK1/2) regulated gene expression in normal and disease states. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2023, 101, 204–219. [Google Scholar]

- Tochiki, K.K.; Maiarú, M.; Norris, C.; Hunt, S.P.; Géranton, S.M. The mitogen and stress-activated protein kinase 1 regulates the rapid epigenetic tagging of dorsal horn neurons and nocifensive behaviour. Pain 2016, 157, 2594–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Pérez, J.V.; Sántha, P.; Varga, A.; Szucs, P.; Sousa-Valente, J.; Gaal, B.; Nagy, I. Phosphorylated Histone 3 at Serine 10 Identifies Activated Spinal Neurons and Contributes to the Development of Tissue Injury-Associated Pain. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Gao, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Liang, Z.; Xu, J.T.; Li, L. Activation of MSK-1 exacerbates neuropathic pain through histone H3 phosphorylation in the rats’ dorsal root ganglia and spinal dorsal horn. Brain Res. Bull. 2024, 219, 111135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irfan, J.; Febrianto, R.M.; La Montanara, P.; Meng, M.Y.; Hutson, T.H.; Zimmermann, D.; Deak-Pocsai, K.; Aldossary, D.; Wang, J.; Di Giovanni, S.; et al. Mitogen- and stress-activated kinase 1 in primary sensory neurons contributes to formalin-induced tonic pain. Pain Rep. 2025, 10, e1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basbaum, A.I.; Bautista, D.M.; Scherrer, G.; Julius, D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell 2009, 139, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, A.J. Neuronal circuitry for pain processing in the dorsal horn. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloaga, A.; Thomson, S.; Wiggin, G.R.; Rampersaud, N.; Dyson, M.H.; Hazzalin, C.A.; Arthur, J.S.C. MSK2 and MSK1 mediate the mitogen-and stress-induced phosphorylation of histone H3 and HMG-14. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 2788–2797. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, A.; Mészár, Z.; Sivadó, M.; Bácskai, T.; Végh, B.; Kókai, É.; Nagy, I.; Szücs, P. Spinal excitatory dynorphinergic interneurons contribute to burn injury-induced nociception mediated by phosphorylated histone 3 at serine 10 in rodents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejwani, L.; Ravindra, N.G.; Lee, C.; Cheng, Y.; Nguyen, B.; Luttik, K.; Ni, L.; Zhang, S.; Morrison, L.M.; Gionco, J.; et al. Longitudinal single-cell transcriptional dynamics throughout neurodegeneration in SCA1. Neuron 2024, 112, 362–383.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Gupta, R.R.; Scheurer, L.; Pelczar, P.; Wildner, H.; Zeilhofer, H.U. Neuron-specific spinal cord translatomes reveal a neuropeptide code for mouse dorsal horn excitatory neurons. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Barrio, M.G.; Bourane, S.; Grossmann, K.; Schüle, R.; Britsch, S.; O’Leary, D.D.; Goulding, M. A transcription factor code defines nine sensory interneuron subtypes in the mechanosensory area of the spinal cord. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77928. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, E.; Wildner, H.; Tudeau, L.; Haueter, S.; Ralvenius, W.T.; Jegen, M.; Johannssen, H.; Hösli, L.; Haenraets, K.; Ghanem, A.; et al. Targeted ablation, silencing, and activation establish glycinergic dorsal horn neurons as key components of a spinal gate for pain and itch. Neuron 2015, 85, 1289–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, M. Pax2 is persistently expressed by GABAergic neurons throughout the adult rat dorsal horn. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 638, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, N.E.; da Silva, R.V.; Sotocinal, S.G.; Zeilhofer, H.U.; Mogil, J.S.; Kania, A. Hoxb8 intersection defines a role for Lmx1b in excitatory dorsal horn neuron development, spinofugal connectivity, and nociception. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 5233–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, D.E.; Cross, R.B.P.; Li, L.; Koch, S.C.; Matson, K.J.E.; Yadav, A.; Alkaslasi, M.R.; Lee, D.I.; Le Pichon, C.E.; Menon, V.; et al. A harmonized atlas of mouse spinal cord cell types and their spatial organization. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mészár, Z.; Kókai, É.; Varga, R.; Ducza, L.; Papp, T.; Béresová, M.; Nagy, M.; Szücs, P.; Varga, A. CRISPR/Cas9-Based mutagenesis of histone H3.1 in spinal dynorphinergic neurons attenuates thermal sensitivity in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, C.R.; Mandel-Brehm, J.; Bautista, D.M.; Siemens, J.; Deranian, K.L.; Zhao, M.; Hayward, N.J.; Chong, J.A.; Julius, D.; Moran, M.M.; et al. TRPA1 mediates formalin-induced pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 13525–13530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.R.; Befort, K.; Brenner, G.J.; Woolf, C.J. ERK MAP kinase activation in superficial spinal cord neurons induces prodynorphin and NK-1 upregulation and contributes to persistent inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggin, G.R.; Soloaga, A.; Foster, J.M.; Murray-Tait, V.; Cohen, P.; Arthur, J.S. MSK1 and MSK2 are required for the mitogen- and stress-induced phosphorylation of CREB and ATF1 in fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 2871–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuck, S.; Soloaga, A.; Schratt, G.; Arthur, J.S.; Nordheim, A. The kinase MSK1 is required for induction of c-fos by lysophosphatidic acid in mouse embryonic stem cells. BMC Mol. Biol. 2003, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.L.; Dhillon, S.S.; Belsham, D.D. Kisspeptin directly regulates neuropeptide Y synthesis and secretion via the ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways in NPY-secreting hypothalamic neurons. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 5038–5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Ganga, M.; García-Yagüe, Á.J.; Lastres-Becker, I. Role of MSK1 in the induction of NF-κB by the chemokine CX3CL1 in microglial cells. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 39, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, L.; De Wilde, G.; Van Damme, P.; Vanden Berghe, W.; Haegeman, G. Transcriptional activation of the NF-kappaB p65 subunit by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1 (MSK1). EMBO J. 2003, 22, 1313–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, C.M.; Hedrick, M.N.; Izadi, H.; Bates, T.C.; Olivera, E.R.; Anguita, J. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase controls NF-kappaB transcriptional activation and tumor necrosis factor alpha production through RelA phosphorylation mediated by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 in response to Borrelia burgdorferi antigens. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogatzki-Zahn, E.M.; Gomez-Varela, D.; Erdmann, G.; Kaschube, K.; Segelcke, D.; Schmidt, M. A proteome signature for acute incisional pain in dorsal root ganglia of mice. Pain 2021, 162, 2070–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Irfan, J.; Febrianto, R.M.; Mira D’Ercole, A.; Li, N.; Danke, V.; Chen, E.; Aldossary, D.; Meng, M.Y.; La Montanara, P.; Torres-Perez, J.V.; et al. MSK1 Downstream Signaling Contributes to Inflammatory Pain in the Superficial Spinal Dorsal Horn. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412177

Irfan J, Febrianto RM, Mira D’Ercole A, Li N, Danke V, Chen E, Aldossary D, Meng MY, La Montanara P, Torres-Perez JV, et al. MSK1 Downstream Signaling Contributes to Inflammatory Pain in the Superficial Spinal Dorsal Horn. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412177

Chicago/Turabian StyleIrfan, Jahanzaib, Rizki Muhammad Febrianto, Angelina Mira D’Ercole, Nicole Li, Vijaya Danke, Erica Chen, Deemah Aldossary, Michelle Y. Meng, Paolo La Montanara, Jose Vicente Torres-Perez, and et al. 2025. "MSK1 Downstream Signaling Contributes to Inflammatory Pain in the Superficial Spinal Dorsal Horn" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412177

APA StyleIrfan, J., Febrianto, R. M., Mira D’Ercole, A., Li, N., Danke, V., Chen, E., Aldossary, D., Meng, M. Y., La Montanara, P., Torres-Perez, J. V., Zimmermann, D., Li, R., Deak-Pocsai, K., Segelcke, D., Pradier, B., Pogatzki-Zahn, E. M., Giovanni, S. D., Kress, M., & Nagy, I. (2025). MSK1 Downstream Signaling Contributes to Inflammatory Pain in the Superficial Spinal Dorsal Horn. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412177