Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer

Abstract

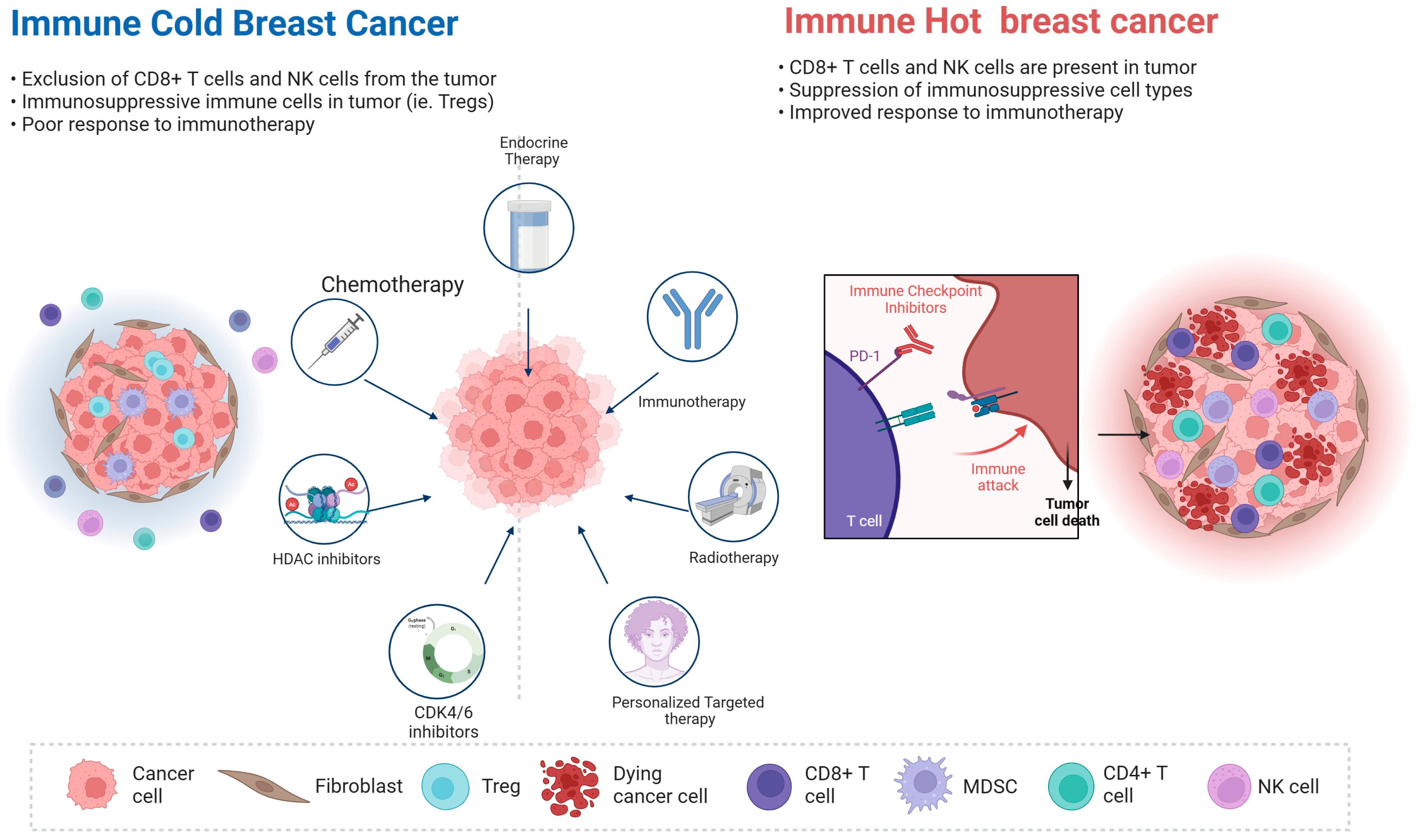

1. Introduction

2. ICI in Metastatic Breast Cancer

2.1. ICI Monotherapy (with or Without Aromatase Inhibitor) in HR+/HER2− MBC

2.2. ICI Combinations in HR+/HER2− MBC

2.3. Chemo-Immunotherapy Combinations in HR+/HER2− MBC

2.4. Targeted Therapy and ICI Combinations in HR+/HER2− MBC

2.4.1. ICI Plus HDAC Inhibitor or AKT Inhibitor in HR+/HER2− MBC

2.4.2. ICI Plus CDK4/6 Inhibitors in HR+/HER2− MBC

2.4.3. ICI Plus PARP Inhibitors in HR+/HER2− MBC

2.5. ICI Plus Radiation Therapy in HR+/HER2− MBC

3. Neoadjuvant ICI in HR+/HER2− Early-Stage Breast Cancer

3.1. Neoadjuvant CDK4/6i and Nivolumab in HR+/HER2− EBC

3.2. Neoadjuvant ISPY2 Trial in HR+/HER2− EBC

3.3. Neoadjuvant GIADA Trial in HR+/HER2− EBC

3.4. Neoadjuvant KEYNOTE-756 Trial in HR+/HER2− EBC

3.5. Neoadjuvant CheckMate 7FL Trial in HR+/HER2− EBC

3.6. Neoadjuvant Radiation and ICI Trial in HR+/HER2− EBC

3.7. Other Ongoing Neoadjuvant ICI Trials in HR+/HER2− EBC

| Trial Name | Phase | Eligible Stages | Treatment Arms | Cohort | pCR | Additional Outcomes | Safety and Toxicities | Biomarker | NCT | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CheckMate 7A8 | 2 | cT1c-T3, ≥2 cm tumor | Nivolumab + palbociclib (125 mg: 100 mg) + anastrozole | 9:12 | 0%:8% | 0%:8% RCB 0–1 | 89%:75% G3/4 AEs, and a total of nine pts discontinued due to AEs | PD-L1 | NCT04075604 | [51] |

| I-SPY2 | 2 | T2-T3, ≥2.5 cm tumor (clinical) or ≥2 cm tumor (imaging) | Paclitaxel ± pembrolizumab → ddAC (P + P:P) | 40:96 | 30%:13% | 46%:24% RCB 0–1 | 29:33 G3/4 AEs were reported (includes TNBC pts, N = 69: 181) * | MP | NCT01042379 | [53] |

| GIADA | 2 | T2-3a, LumB-like BC (Ki67 ≥ 20% and/or histologic G3) | EC + triptorelin → nivolumab + exemestane | 43 | 16% | 26% RCB 0–1 | 30 G3/4 AEs were reported, and nine pts discontinued due to AEs | Breast Cancer 360TM TILs | NCT04659551 | [55] |

| KEYNOTE 756 | 3 | cT1c-2 (≥2 cm) N1-2 or cT3–4 N0-2; G3 | Paclitaxel ± pembrolizumab → ddAC (P + P:P) | 635:643 | 24%:16% | 35%:24% RCB 0–1 | 53%:46% G3+ TRAEs, 121: 65 pts discontinued, and one death in P + P arm due to TRAEs | PD-L1 | NCT03725059 | [56] |

| CheckMate 7FL | 3 | 2–5 cm cN1-2 or cT3-4 cN0-2; G3 or G2 if ER 1-10% | Paclitaxel ± nivolumab → ddAC ± nivolumab (P + N:P) | 257:253 | 25%:14% | 31%:21% RCB 0–1 EFS rate 89%:92% | 35%:32% G3/4 TRAEs, 30: seven pts discontinued due to AEs; in P + N arm, there are three G5 treatment-unrelated AEs, and two deaths due to TRAEs | PD-L1 TILs | NCT04109066 | [57] |

| PEARL | 1/2b | cT1-3 (≥2 cm); High risk (2 of: G2-3, Ki67 ≥ 20%, ER < 75%) | Pembrolizumab → RT → NACT (regimen decided by treating physician) | 12 | 33% | 42% RCB 0–1 | 41% G3/4 AEs, and 14% G3 TRAEs | PD-L1 TILs | NCT03366844 | [60] |

| Neo-CheckRay (2023) | 1b | cT2-3 N0 or T1b-3 N1-3, Ki67 ≥ 15% or G3; MP high-risk | Paclitaxel + durvalumab + oleclumab + RT → ddAC + durvalumab + oleclumab | 6 | 33% | 66% RCB 0–1 | 17% G3/4 AEs | TILs, PD-L1, CD73 and MHC-I | NCT03875573 | [61] |

| Neo-CheckRay (2025) | 2 | cT2-3 N0 or T1b-3 N1-3, Ki67 ≥ 15% or G3; MP high-risk | Paclitaxel ± durvalumab ± oleclumab + RT → ddAC + durvalumab + oleclumab (P + D + O:P + D:P) | 45:45 **:45 | 36%:30% **:18% | 51%:49% **:38% RCB 0–1 | 71%:65%:27% G3/4 TRAEs | TILs, PD-L1, CD73 and BMI | NCT03875573 | [62,64] |

| SWOG S2206 | 3 | cT2-3 and MP-High2 | AC-T ± durvalumab (A + D:A) | accruing | NA | NA | NA | PD-1, PD-L1 | NCT06058377 | [67] |

4. Biomarkers Predicting Response to ICI in HR+/HER2− EBC

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AE | Adverse event |

| AI | Aromatase inhibitor |

| AKT | Ak strain transforming |

| ALT | Alanine transaminase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BC | Breast cancer |

| BP | Blueprint |

| BRCA | Breast cancer gene |

| CBR | Clinical benefit rate |

| CDK4/6i | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor |

| CPS | Combined positive score |

| CT | Chemotherapy |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| DCR | Disease control rate |

| ddAC | Dose-dense doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide |

| DDR | DNA damage response |

| DOR | Duration of response |

| EBC | Early breast cancer |

| EC | Epirubicin plus cyclophosphamide |

| EFS | Event-free survival |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| ET | Endocrine therapy |

| FOXP3 | Forkhead box P3 |

| HDAC | Histone Deacetylase |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| IDFS | Invasive disease-free survival |

| ILD | Interstitial lung disease |

| KN-756 | KEYNOTE-756 |

| LAG3 | Lymphocyte activation gene 3 |

| LumB | Luminal B |

| MBC | Metastatic breast cancer |

| mDOR | Median duration of response |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| mo | months |

| MP | Mammaprint |

| mPFS | Median progression free survival |

| mTNBC | Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer |

| mut/MB | Mutations per Megabase |

| NA | Not applicable |

| NACT | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

| NR | Not reported |

| ORR | Objective response rate |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PAM50 | Prediction analysis of microarray 50 |

| PARPi | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor |

| pCR | Pathological complete response |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed cell death-ligand 1 |

| PR | Partial response |

| RCB | Residual cancer burden |

| RT | Radiation therapy |

| SBRT | Stereotactic body radiation therapy |

| SD | Stable disease |

| STING | Stimulator of interferon genes |

| TAM | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| TIL | Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes |

| TMB | Tumor mutation burden |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| TRAE | Treatment-related adverse events |

| Treg | Regulatory T cells |

References

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Miller, K.D.; Kramer, J.L.; Newman, L.A.; Minihan, A.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 524–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, K.; Giordano, S.; Leone, J.P. Immunotherapy in breast cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.R.; Toi, M.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Rastogi, P.; Campone, M.; Neven, P.; Huang, C.-S.; Huober, J.; Jaliffe, G.G.; Cicin, I. Abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy for hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, node-positive, high-risk early breast cancer (monarchE): Results from a preplanned interim analysis of a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hortobagyi, G.; Lacko, A.; Sohn, J.; Cruz, F.; Borrego, M.R.; Manikhas, A.; Park, Y.H.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Yardley, D.; Huang, C.-S. A phase III trial of adjuvant ribociclib plus endocrine therapy versus endocrine therapy alone in patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative early breast cancer: Final invasive disease-free survival results from the NATALEE trial. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bairi, K.; Haynes, H.R.; Blackley, E.; Fineberg, S.; Shear, J.; Turner, S.; De Freitas, J.R.; Sur, D.; Amendola, L.C.; Gharib, M. The tale of TILs in breast cancer: A report from the international immuno-oncology biomarker working group. npj Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, J.; Cescon, D.W.; Rugo, H.S.; Nowecki, Z.; Im, S.-A.; Yusof, M.M.; Gallardo, C.; Lipatov, O.; Barrios, C.H.; Holgado, E.; et al. KEYNOTE-355: Randomized, double-blind, phase III study of pembrolizumab + chemotherapy versus placebo + chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.; Kümmel, S.; Bergh, J.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.; Hui, R.; Harbeck, N. Pembrolizumab for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado, R.; Denkert, C.; Campbell, C.; Savas, P.; Nuciforo, P.; Aura, C.; De Azambuja, E.; Eidtmann, H.; Ellis, C.E.; Baselga, J. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and associations with pathological complete response and event-free survival in HER2-positive early-stage breast cancer treated with lapatinib and trastuzumab: A secondary analysis of the NeoALTTO trial. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefaard, M.C.; van der Voort, A.; van Seijen, M.; Thijssen, B.; Sanders, J.; Vonk, S.; Mittempergher, L.; Bhaskaran, R.; de Munck, L.; van Leeuwen-Stok, A.E.; et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in HER2-positive breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and dual HER2-blockade. npj Breast Cancer 2024, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimino-Mathews, A.; Thompson, E.; Taube, J.M.; Ye, X.; Lu, Y.; Meeker, A.; Xu, H.; Sharma, R.; Lecksell, K.; Cornish, T.C.; et al. PD-L1 (B7-H1) expression and the immune tumor microenvironment in primary and metastatic breast carcinomas. Hum. Pathol. 2016, 47, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasniqi, E.; Barchiesi, G.; Pizzuti, L.; Mazzotta, M.; Venuti, A.; Maugeri-Saccà, M.; Sanguineti, G.; Massimiani, G.; Sergi, D.; Carpano, S. Immunotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: State of the art and future perspectives. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, J.; Pastorello, R.G.; Vallius, T.; Davis, J.; Cui, Y.X.; Agudo, J.; Waks, A.G.; Keenan, T.; McAllister, S.S.; Tolaney, S.M. The immunology of hormone receptor positive breast cancer. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 674192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Tan, J.; Lin, D.; Lee, J.S.; Yuan, Y. Immunotherapy in Breast Cancer: Beyond Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonderheide, R.H.; LoRusso, P.M.; Khalil, M.; Gartner, E.M.; Khaira, D.; Soulieres, D.; Dorazio, P.; Trosko, J.A.; Rüter, J.; Mariani, G.L.; et al. Tremelimumab in combination with exemestane in patients with advanced breast cancer and treatment-associated modulation of inducible costimulator expression on patient T cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3485–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugo, H.S.; Delord, J.P.; Im, S.A.; Ott, P.A.; Piha-Paul, S.A.; Bedard, P.L.; Sachdev, J.; Le Tourneau, C.; van Brummelen, E.M.J.; Varga, A.; et al. Safety and Antitumor Activity of Pembrolizumab in Patients with Estrogen Receptor-Positive/Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 2804–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirix, L.Y.; Takacs, I.; Jerusalem, G.; Nikolinakos, P.; Arkenau, H.-T.; Forero-Torres, A.; Boccia, R.; Lippman, M.E.; Somer, R.; Smakal, M. Avelumab, an anti-PD-L1 antibody, in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer: A phase 1b JAVELIN Solid Tumor study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 167, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Yost, S.E.; Lee, J.S.; Frankel, P.H.; Ruel, C.; Cui, Y.; Murga, M.; Tang, A.; Martinez, N.; Chung, S. Phase II Study Combining Pembrolizumab with Aromatase Inhibitor in Patients with Metastatic Hormone Receptor Positive Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, N.; Moore, D.; Baka, N.; Wisinski, K.; Krisnamurthy, J.; Rana, J.; Tandra, P.; Marks, D.; West, M.; Tamkus, D. Abstract P2-07-21: A phase II study of pembrolizumab plus fulvestrant in ER positive, HER2 negative advanced/metastatic breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, P2-07-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso-Sousa, R.; Zanudo, J.G.T.; Li, T.; Reddy, S.M.; Emens, L.A.; Kuntz, T.M.; Silva, C.A.C.; AlDubayan, S.H.; Chu, H.; Overmoyer, B. Nivolumab plus low-dose ipilimumab in hypermutated HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: A phase II trial (NIMBUS). Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Maria, C.A.; Kato, T.; Park, J.-H.; Kiyotani, K.; Rademaker, A.; Shah, A.N.; Gross, L.; Blanco, L.Z.; Jain, S.; Flaum, L. A pilot study of durvalumab and tremelimumab and immunogenomic dynamics in metastatic breast cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 18985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameiro, S.R.; Caballero, J.A.; Hodge, J.W. Defining the molecular signature of chemotherapy-mediated lung tumor phenotype modulation and increased susceptibility to T-cell killing. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2012, 27, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattarollo, S.R.; Loi, S.; Duret, H.; Ma, Y.; Zitvogel, L.; Smyth, M.J. Pivotal role of innate and adaptive immunity in anthracycline chemotherapy of established tumors. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 4809–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurr, M.; Pembroke, T.; Bloom, A.; Roberts, D.; Thomson, A.; Smart, K.; Bridgeman, H.; Adams, R.; Brewster, A.; Jones, R. Low-dose cyclophosphamide induces antitumor T-cell responses, which associate with survival in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 6771–6780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.N.; Flaum, L.; Helenowski, I.; Santa-Maria, C.A.; Jain, S.; Rademaker, A.; Nelson, V.; Tsarwhas, D.; Cristofanilli, M.; Gradishar, W. Phase II study of pembrolizumab and capecitabine for triple negative and hormone receptor-positive, HER2− negative endocrine-refractory metastatic breast cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolaney, S.M.; Barroso-Sousa, R.; Keenan, T.; Li, T.; Trippa, L.; Vaz-Luis, I.; Wulf, G.; Spring, L.; Sinclair, N.F.; Andrews, C. Effect of eribulin with or without pembrolizumab on progression-free survival for patients with hormone receptor–positive, ERBB2-negative metastatic breast cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, I.; Haag, G.; Rahma, O.; Macarulla, T.; McCune, S.; Yardley, D.; Solomon, B.; Johnson, M.; Vidal, G.; Schmid, P. MORPHEUS: A phase Ib/II umbrella study platform evaluating the safety and efficacy of multiple cancer immunotherapy (CIT)-based combinations in different tumour types. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, viii439–viii440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenblick, A.; Im, S.; Lee, K.; Tan, A.; Telli, M.; Shachar, S.S.; Tchaleu, F.B.; Cha, E.; DuPree, K.; Nikanjam, M. 267P Phase Ib/II open-label, randomized evaluation of second-or third-line (2L/3L) atezolizumab (atezo)+ entinostat (entino) in MORPHEUS-HR+ breast cancer (M-HR+ BC). Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, S479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurvitz, S.A.; Boni, V.; Comen, E.; Im, S.-A.; Jung, K.H.; Kim, S.-B.; Lee, K.S.; Loi, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Sonnenblick, A. Abstract PD10-04: Phase Ib/II open-label, randomized trial of atezolizumab (atezo) with ipatasertib (ipat) and fulvestrant (fulv) vs control in MORPHEUS-HR+ breast cancer (M-HR+ BC) and atezo with ipat vs control in MORPHEUS triple negative breast cancer (M-TNBC). Cancer Res. 2022, 82, PD10-04. [Google Scholar]

- Terranova-Barberio, M.; Pawlowska, N.; Dhawan, M.; Moasser, M.; Chien, A.J.; Melisko, M.E.; Rugo, H.; Rahimi, R.; Deal, T.; Daud, A.; et al. Exhausted T cell signature predicts immunotherapy response in ER-positive breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, S.; DeCristo, M.J.; Watt, A.C.; BrinJones, H.; Sceneay, J.; Li, B.B.; Khan, N.; Ubellacker, J.M.; Xie, S.; Metzger-Filho, O.; et al. CDK4/6 inhibition triggers anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2017, 548, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Wang, E.S.; Jenkins, R.W.; Li, S.; Dries, R.; Yates, K.; Chhabra, S.; Huang, W.; Liu, H.; Aref, A.R.; et al. CDK4/6 Inhibition Augments Antitumor Immunity by Enhancing T-cell Activation. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Lee, J.S.; Yost, S.E.; Frankel, P.H.; Ruel, C.; Egelston, C.A.; Guo, W.; Padam, S.; Tang, A.; Martinez, N. Phase I/II trial of palbociclib, pembrolizumab and letrozole in patients with hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 154, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egelston, C.; Guo, W.; Yost, S.; Lee, J.S.; Rose, D.; Avalos, C.; Ye, J.; Frankel, P.; Schmolze, D.; Waisman, J. Pre-existing effector T-cell levels and augmented myeloid cell composition denote response to CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib and pembrolizumab in hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e02084. [Google Scholar]

- LeVee, A.A.; Egelston, C.A.; Yost, S.E.; Frankel, P.H.; Lee, K.; Ruel, C.; Schmolze, D.; Lee, P.P.; Yeon, C.H.; Yuan, Y.; et al. A phase I/II trial of palbociclib, pembrolizumab, and endocrine therapy for patients with HR+/HER2- locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC): Clinical outcomes and stool microbial profiling. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugo, H.S.; Kabos, P.; Beck, J.T.; Jerusalem, G.; Wildiers, H.; Sevillano, E.; Paz-Ares, L.; Chisamore, M.J.; Chapman, S.C.; Hossain, A.M. Abemaciclib in combination with pembrolizumab for HR+, HER2− metastatic breast cancer: Phase 1b study. npj Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, J.; Sakai, H.; Tsurutani, J.; Tanabe, Y.; Masuda, N.; Iwasa, T.; Takahashi, M.; Futamura, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Aogi, K. Efficacy, safety, and biomarker analysis of nivolumab in combination with abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy in patients with HR-positive HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: A phase II study (WJOG11418B NEWFLAME trial). J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e007126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.H.; Im, S.-A.; Yardley, D.; Hurvitz, S.; Lee, K.S.; Sonnenblick, A.; Shachar, S.; Tan, A.; Comen, E.; Gal-Yam, E. Abstract PS12-08: MORPHEUS Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: Interim analysis of a Phase Ib/II, study of fulvestrant±atezolizumab and abemaciclib triplet treatment in patients metastatic disease. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, PS12-08-PS12-08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Sonnenblick, A.; Stemmer, S.M.; Gion, M.; Im, S.-A.; Bermejo, B.; Gal Yam, E.; Sohn, J.; Wander, S.A.; Rugo, H.S. Giredestrant (G) with atezolizumab (ATEZO), and/or abemaciclib (ABEMA) in patients (pts) with ER+/HER2–locally advanced/metastatic breast cancer (LA/mBC): Interim analysis (IA) from the phase I/II MORPHEUS Breast Cancer study. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 1061. [Google Scholar]

- Peyraud, F.; Italiano, A. Combined PARP Inhibition and Immune Checkpoint Therapy in Solid Tumors. Cancers 2020, 12, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domchek, S.M.; Postel-Vinay, S.; Im, S.-A.; Park, Y.H.; Delord, J.-P.; Italiano, A.; Alexandre, J.; You, B.; Bastian, S.; Krebs, M.G. Olaparib and durvalumab in patients with germline BRCA-mutated metastatic breast cancer (MEDIOLA): An open-label, multicentre, phase 1/2, basket study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.A.; Bardia, A.; Dvorkin, M.; Galsky, M.D.; Beck, J.T.; Wise, D.R.; Karyakin, O.; Rubovszky, G.; Kislov, N.; Rohrberg, K.; et al. Avelumab Plus Talazoparib in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors: The JAVELIN PARP Medley Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Kim, H.-J.; Wang, Q.; Kearns, M.; Jiang, T.; Ohlson, C.E.; Li, B.B.; Xie, S.; Liu, J.F.; Stover, E.H. PARP inhibition elicits STING-dependent antitumor immunity in Brca1-deficient ovarian cancer. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 2972–2980. e2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Kong, L.; Shi, F.; Zhu, H.; Yu, J. Abscopal effect of radiotherapy combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.Y.; Barker, C.A.; Arnold, B.B.; Powell, S.N.; Hu, Z.I.; Gucalp, A.; Lebron-Zapata, L.; Wen, H.Y.; Kallman, C.; D’Agnolo, A.; et al. A phase 2 clinical trial assessing the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab and radiotherapy in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer 2020, 126, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Young, S.; Boldt, G.; Blanchette, P.; Lock, M.; Helou, J.; Raphael, J. Immunotherapy and Radiation Therapy Sequencing in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2024, 118, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso-Sousa, R.; Krop, I.E.; Trippa, L.; Tan-Wasielewski, Z.; Li, T.; Osmani, W.; Andrews, C.; Dillon, D.; Richardson, E.T., III; Pastorello, R.G. A phase II study of pembrolizumab in combination with palliative radiotherapy for hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 2020, 20, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, M.; Yoshimura, M.; Kotake, T.; Kawaguchi, K.; Uozumi, R.; Kataoka, M.; Kato, H.; Yoshibayashi, H.; Suwa, H.; Tsuji, W. Phase Ib/II study of nivolumab combined with palliative radiation therapy for bone metastasis in patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, L.A.; Wolf, D.; Yau, C.; Brown-Swigart, L.; Hirst, G.L.; Isaacs, C.; Pusztai, L.; Pohlmann, P.R.; DeMichele, A.; Shatsky, R.; et al. Pathologic complete response (pCR) rates for patients with HR+/HER2− high-risk, early-stage breast cancer (EBC) by clinical and molecular features in the phase II I-SPY2 clinical trial. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symmans, W.F.; Wei, C.; Gould, R.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Walls, A.; Bousamra, A.; Ramineni, M.; Sinn, B. Long-term prognostic risk after neoadjuvant chemotherapy associated with residual cancer burden and breast cancer subtype. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrisi, R.; Marrazzo, E.; Agostinetto, E.; De Sanctis, R.; Losurdo, A.; Masci, G.; Tinterri, C.; Santoro, A. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative early breast cancer: When, why and what? Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2021, 160, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerusalem, G.; Prat, A.; Salgado, R.; Reinisch, M.; Saura, C.; Ruiz-Borrego, M.; Nikolinakos, P.; Ades, F.; Filian, J.; Huang, N.; et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab + palbociclib + anastrozole for oestrogen receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative primary breast cancer: Results from CheckMate 7A8. Breast 2023, 72, 103580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, M.R.; McGuinness, J.E.; Kalinsky, K. Clinical trial data and emerging immunotherapeutic strategies: Hormone receptor-positive, HER2- negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 189, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, R.; Liu, M.C.; Yau, C.; Shatsky, R.; Pusztai, L.; Wallace, A.; Chien, A.J.; Forero-Torres, A.; Ellis, E.; Han, H. Effect of pembrolizumab plus neoadjuvant chemotherapy on pathologic complete response in women with early-stage breast cancer: An analysis of the ongoing phase 2 adaptively randomized I-SPY2 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 676–684. [Google Scholar]

- Mittempergher, L.; Kuilman, M.M.; Barcaru, A.; Nota, B.; Delahaye, L.J.M.J.; Audeh, M.W.; Wolf, D.M.; Yau, C.; Swigart, L.B.; Hirst, G.L.; et al. The ImPrint immune signature to identify patients with high-risk early breast cancer who may benefit from PD1 checkpoint inhibition in I-SPY2. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieci, M.V.; Guarneri, V.; Tosi, A.; Bisagni, G.; Musolino, A.; Spazzapan, S.; Moretti, G.; Vernaci, G.M.; Griguolo, G.; Giarratano, T.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy in Luminal B-like Breast Cancer: Results of the Phase II GIADA Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Liu, Z.; McArthur, H.; Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Harbeck, N.; Telli, M.L.; Cescon, D.W.; Fasching, P.A. Pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in high-risk, early-stage, ER+/HER2− breast cancer: A randomized phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, S.; Salgado, R.; Curigliano, G.; Romero Díaz, R.I.; Delaloge, S.; Rojas García, C.I.; Kok, M.; Saura, C.; Harbeck, N.; Mittendorf, E.A.; et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab and chemotherapy in early estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: A randomized phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaria, S.; Kawashima, N.; Yang, A.M.; Devitt, M.L.; Babb, J.S.; Allison, J.P.; Formenti, S.C. Immune-mediated inhibition of metastases after treatment with local radiation and CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model of breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaria, S.; Bhardwaj, N.; McBride, W.H.; Formenti, S.C. Combining radiotherapy and immunotherapy: A revived partnership. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2005, 63, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ho, A.Y.; Shiao, S.; Kobald, S.A.; Chen, J.; Duda, D.G.; Ly, A.; Bossuyt, V.; Cho, H.L.; Arnold, B.; Knott, S.; et al. PEARL: A Phase Ib/II Biomarker Study of Adding Radiation Therapy to Pembrolizumab Before Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2–Negative Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 4282–4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Caluwe, A.; Romano, E.; Poortmans, P.; Gombos, A.; Agostinetto, E.; Marta, G.N.; Denis, Z.; Drisis, S.; Vandekerkhove, C.; Desmet, A.; et al. First-in-human study of SBRT and adenosine pathway blockade to potentiate the benefit of immunochemotherapy in early-stage luminal B breast cancer: Results of the safety run-in phase of the Neo-CheckRay trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e007279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Caluwé, A.; Buisseret, L.; Poortmans, P.; Van Gestel, D.; Salgado, R.; Sotiriou, C.; Larsimont, D.; Paesmans, M.; Craciun, L.; Stylianos, D.; et al. Neo-CheckRay: Radiation therapy and adenosine pathway blockade to increase benefit of immuno-chemotherapy in early stage luminal B breast cancer, a randomized phase II trial. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Caluwé, A.; Bellal, S.; Cao, K.; Peignaux, K.; Remouchamps, V.; Baten, A.; Longton, E.; Bessieres, I.; Vu-Bezin, J.; Kirova, Y.; et al. Adapting radiation therapy to immunotherapy: Delineation and treatment planning of pre-operative immune-modulating breast iSBRT in 151 patients treated in the randomized phase II Neo-CheckRay trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2025, 206, 110836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Caluwe, A.; Desmoulins, I.; Cao, K.; Remouchamps, V.; Baten, A.; Longton, E.; Peignaux-Casasnovas, K.; Nader-Marta, G.; Arecco, L.; Agostinetto, E.; et al. LBA10 Primary endpoint results of the Neo-CheckRay phase II trial evaluating stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) +/- durvalumab (durva) +/- oleclumab (ole) combined with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) for early-stage, high risk ER+/HER2- breast cancer (BC). Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaitelman, S.F.; Woodward, W.A. Neoadjuvant radioimmunotherapy synergy in triple-negative breast cancer: Is microenvironment-guided patient selection on the horizon? Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litton, J.K.; Regan, M.M.; Pusztai, L.; Rugo, H.S.; Tolaney, S.M.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; Amiri-Kordestani, L.; Basho, R.K.; Best, A.F.; Boileau, J.F.; et al. Standardized Definitions for Efficacy End Points in Neoadjuvant Breast Cancer Clinical Trials: NeoSTEEP. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4433–4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobain, E.F.; Pusztai, L.; Graham, C.L.; Whitworth, P.W.; Beitsch, P.D.; Osborne, C.R. Elucidating the immune active state of HR+ HER2-MammaPrint High 2 early breast cancer. JCO 2024, 42, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkert, C.; von Minckwitz, G.; Darb-Esfahani, S.; Lederer, B.; Heppner, B.I.; Weber, K.E.; Budczies, J.; Huober, J.; Klauschen, F.; Furlanetto, J. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: A pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagami, P.; Cortés, J.; Carey, L.; Curigliano, G. Immunotherapy in the treatment landscape of hormone receptor-positive (HR+) early breast cancer: Is new data clinical practice changing? ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, D.M.; Yau, C.; Campbell, M.; Glas, A.; Barcaru, A.; Mittempergher, L.; Kuilman, M.; Brown-Swigart, L.; Hirst, G.; Basu, A.; et al. Immune Subtyping Identifies Patients With Hormone Receptor–Positive Early-Stage Breast Cancer Who Respond to Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy (IO): Results From Five IO Arms of the I-SPY2 Trial. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, e2400776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, R.; Denkert, C.; Demaria, S.; Sirtaine, N.; Klauschen, F.; Pruneri, G.; Wienert, S.; Van den Eynden, G.; Baehner, F.L.; Penault-Llorca, F.; et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: Recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trial Name | Phase | Prior Treatment | Treatment Arms | Cohort | ORR | Survival Outcomes | Additional Outcomes | Safety and Toxicities | Biomarker | NCT | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 ICI Monotherapy | |||||||||||

| KEYNOTE-028 (2018) | 1b | Pretreated with ≥1 line of therapy | Pembrolizumab | 25 | 12% | mPFS 1.6 mo mOS 8.6 mo | CBR 20% DOR 12.0 mo | 16% G3/4 AEs, and five pts discontinued due to AEs | PD-L1 | NCT02054806 | [15] |

| JAVELIN Solid Tumor (2018) | 1b | Pretreated with 1–3 lines of therapy | Avelumab | 72 | 3% | mPFS 6.0 weeks mOS 9.2 mo | DCR 28% | 14% G3/4 TRAEs, eight pts discontinued, and two deaths due to TRAEs (all MBC pts, N = 168) * | PD-L1 | NCT01772004 | [16] |

| ICI Monotherapy with endocrine therapy | |||||||||||

| Vonderheide, R.H. et al. (2010) | 1 | Pretreated with ≥1 line of therapy | Tremelimumab + exemestane | 26 | No PR/CR | NA | 42% with SD ≥ 12 weeks | 27% G3 AEs, and one pt discontinued due to TRAEs | Circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells | NA | [14] |

| Ge, X. et al. (2022) | 2 | First line or pretreated with 1–7 lines of therapy | Pembrolizumab + anastrozole/letrozole/exemestane | 20 | 10% | mPFS 1.8 mo mOS 17.2 mo | CBR 20% | 10% G3 AEs | TIL, PD-L1 | NCT02648477 | [17] |

| Chan, N. et al. (2025) | 2 | Pretreated with ≤2 lines of therapy | Pembrolizumab + fulvestrant | 47 | NR | mPFS 3.2 mo | CBR 36% mDOR 6 mo | 15% G3 TRAEs, and one pt discontinued due to TRAEs | PD-L1 | NCT03393845 | [18] |

| 2.2 ICI Combinations | |||||||||||

| Santa-Maria, C.A. et al. (2018) | 2 | Pretreated with ≥1 line of therapy | Durvalumab + tremelimumab | 11 | 0% | NA | CBR 19% | 17 G3 AEs (includes TNBC pts, N = 18) * | none | NCT03393845 | [20] |

| NIMBUS (2025) | 2 | First line or pretreated with 1–3 lines of therapy (1 + ET) | Ipilimumab + nivolumab | 21 | 14% | mPFS 1.4 mo mOS 16.9 mo | NR | 27% G3 AEs, and two pts discontinued due to AEs (includes TNBC pts, N = 30) * | TMB | NCT03789110 | [19] |

| 2.3 Chemo-immunotherapy Combinations | |||||||||||

| Shah, A.N. et al. (2020) | 2 | Pretreated with ≥1 line of ET | Pembrolizumab + capecitabine | 14 | 14% | mPFS 5.1 mo | CBR 28% | G3+ AE in 10+% pts one death from TRAE (includes TNBC pts, N = 16) * | PD-L1 | NCT03044730 | [24] |

| Tolaney, S.M. et al. (2020) | 2 | Pretreated with ≥2 lines of ET and ≤3 chemotherapies | Eribulin ± pembrolizumab (E + P: E alone) | 44:44 | 27%:34% | mPFS 4.1:4.2 mo | CBR 48%:50% | 68%:61% G3/4 AEs, and two deaths due to TRAEs in the E + P arm | PD-L1 TMB TILs | NCT03051659 | [25] |

| 2.4 Targeted therapy and ICI Combinations HDAC inhibitors | |||||||||||

| Terranova-Barberio, M. et al. (2020) | 2 | Pretreated with 1 + lines of therapy | Pembrolizumab + vorinostat + tamoxifen | 34 | 7% | NR | CBR 19% | 33% G3/4 TRAEs, and one pt discontinued due to TRAE | PD-L1 TILs | NCT02395627 | [29] |

| MORPHEUS (2021) | 1b/2 | Pre-treated with 2/3 lines of therapy, but CT-naive | Atezolizumab + entinostat: fulvestrant alone (A + E: F) | 15:14 | 7%:0% | mPFS 1.8:1.8 mo | NR | 40%:21% G3/4 AEs, and one pt discontinued due to TRAE in the A + E arm | PD-L1 | NCT03280563 | [27] |

| AKT inhibitors | |||||||||||

| MORPHEUS (2022) | 1b/2 | Pre-treated with 2/3 lines of therapy, but CT-naive | Atezolizumab + ipatasertib + fulvestrant (A + I + F:F) | 26:15 | 23%:0% | mPFS 4.4:1.9 mo | NR | 62%:20% G3/4 AEs, two pts discontinued due to TRAEs in the A + I + F arm | PD-L1 PI3K status CD8-panCK | NCT03280563 | [28] |

| CDK4/6 inhibitors | |||||||||||

| Yuan, Y. et al. (2021) Cohort 1 | ½ | Pretreated with palbociclib + letrozole for 6+ mo | Pembrolizumab + palbociclib + letrozole | 4 | 50% | NR | CBR 100% | 5 G3/4 TRAEs, and one pt discontinued due to TRAEs | TILs PD-L1 | NCT02778685 | [32] |

| Yuan, Y., et al. (2021) Cohort 2 | 2 | NR | Pembrolizumab + palbociclib + letrozole | 16 | 56% | mPFS 25.2 mo mOS 36.9 mo | CBR 88% | 30 G3/4 TRAEs, and three pts discontinued due to TRAEs | TILs PD-L1 | NCT02778685 | [32] |

| Rugo, H.S. et al. (2020) Cohort 1 | 1b | First line | Pembrolizumab + abemaciclib + anastrozole | 26 | 23% | NR | CBR 39% DCR 85% | 69% G3+ TRAEs, nine pts discontinued, and two deaths due to TRAEs | NR | NCT02779751 | [35] |

| Rugo, H.S. et al. (2020) Cohort 2 | 1b | Pretreated with 1–2 lines of CT | Pembrolizumab + abemaciclib | 28 | 29% | mPFS = 8.9 mo mOS = 26.3 mo | CBR 46% DCR 82% | 54% G3+ TRAEs, six pts discontinued, and one death due to TRAEs | NR | NCT02779751 | [35] |

| WJOG11418B NEWFLAME Ful Cohort (2023) | 2 | First line or pretreated with 1+ lines of ET | Nivolumab + abemaciclib + fulvestrant | 12 | 55% | NR | DCR 91% | 92% G3+ TRAE, and seven pts discontinued due to AEs | PD-L1 | NR | [36] |

| WJOG11418B NEWFLAME Let Cohort (2023) | 2 | First line | Nivolumab + abemaciclib + letrozole | 5 | 40% | NR | DCR 80% | 100% G3+ TRAE, three pts discontinued, and one death due to AEs | PD-L1 | NR | [36] |

| MORPHEUS (2024) | Pretreated with 2/3 lines of therapy, but CT-naive | Fulvestrant ± atezolizumab ± abemaciclib (F + At + Ab:F + At:F) | 38:30:20 | 26%:10%:10% | mPFS 6.3:3.2:2.0 mo | CBR 74%:43%:15% | 82%:27%:15% G3/4 AEs, and 8:2:0 pts discontinued due to AEs | PD-L1, CD8 | NCT03280563 | [37] | |

| PARP inhibitors | |||||||||||

| MEDIOLA (2020) | 1b/2 | Pretreated with 1+ ET and ≤2 CT (must include taxane or anthracycline) | Durvalumab + Olaparib | 16 | NR | mPFS 9.9 mo mOS 22.4 mo | 92% DCR at 12 weeks | 33% AEs, and three pts discontinued due to AEs (including TNBC pts, N = 34) * | PD-L1, TMB | NCT02734004 | [40] |

| JAVELIN PARP Medley (2023) | 2 | Pretreated with 1+ lines of CT | Avelumab + talazoparib | 23 | 35% | mPFS 5.3 mo | DOR 15.7 mo | 57% G3/4 AEs (includes data from all cohorts); one pt discontinued due to TRAE in HR + cohort | PD-L1, TMB, CD8, BRCA | NCT03330405 | [41] |

| 2.5 Radiation and ICI Combinations | |||||||||||

| Barroso-Sousa et al. (2020) | 2 | First line or pretreated with 1+ lines of therapy | Pembrolizumab + RT | 8 | 0% | mPFS 1.4 mo mOS 2.9 mo | CBR 0% | 12.5% G3 AE | PD-L1, TIL | NCT03366844 | [46] |

| KBCRN-B002 (2023) Cohort A | 1b/2 | Pretreated with ≤2 lines of ET and ≤1 line of CT | Nivolumab + RT + ET of the physician’s choice | 18 | 11% | mPFS 4.1 mo | DCR 39% | 0% G3/4 AEs | PD-L1 | NCT03430479 | [47] |

| KBCRN-B002 (2023) Cohort B | 1b/2 | Pretreated with ≥2 lines of CT (must include taxane or anthracycline) | Nivolumab + RT | 8 | 0% | mPFS 2.0 mo | DCR 0% | 9% G3/4 AEs (includes TNBC pts, N = 10) * | PD-L1 | NCT03430479 | [47] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, D.; Bitar, J.S.L.; Ma, I.; Yuan, Y. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412171

Lin D, Bitar JSL, Ma I, Yuan Y. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412171

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, David, Jin Sun Lee Bitar, Isabella Ma, and Yuan Yuan. 2025. "Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412171

APA StyleLin, D., Bitar, J. S. L., Ma, I., & Yuan, Y. (2025). Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412171