Dasatinib and Quercetin Alleviate Retinal Ganglion Cell Dendritic Shrinkage and Promote Axonal Regeneration in Mice with Optic Nerve Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

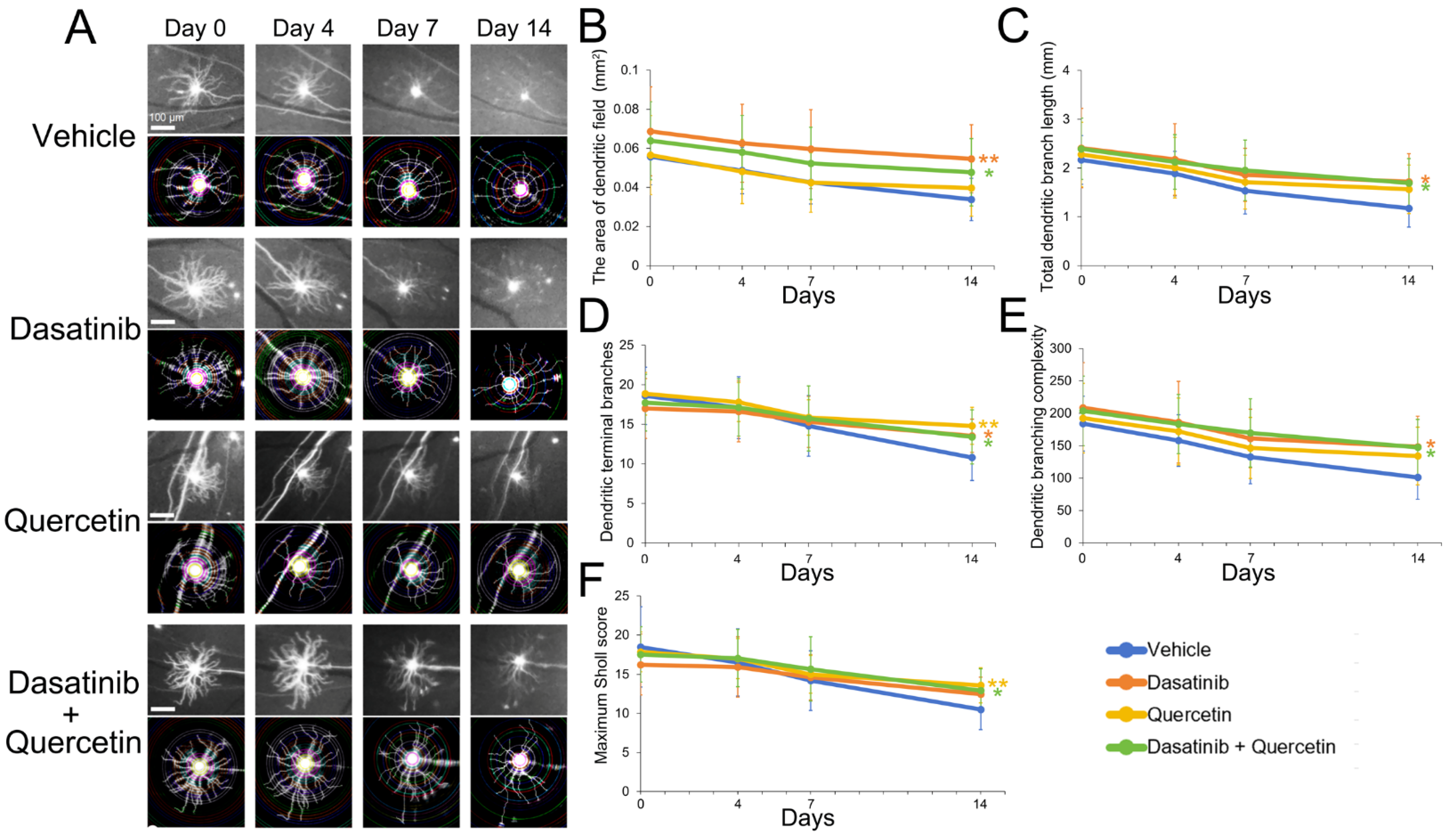

2.1. Dasatinib and Quercetin Treatments Alleviate Retinal Ganglion Cell Dendritic Shrinkage in Mice Post-Optic Nerve Injury

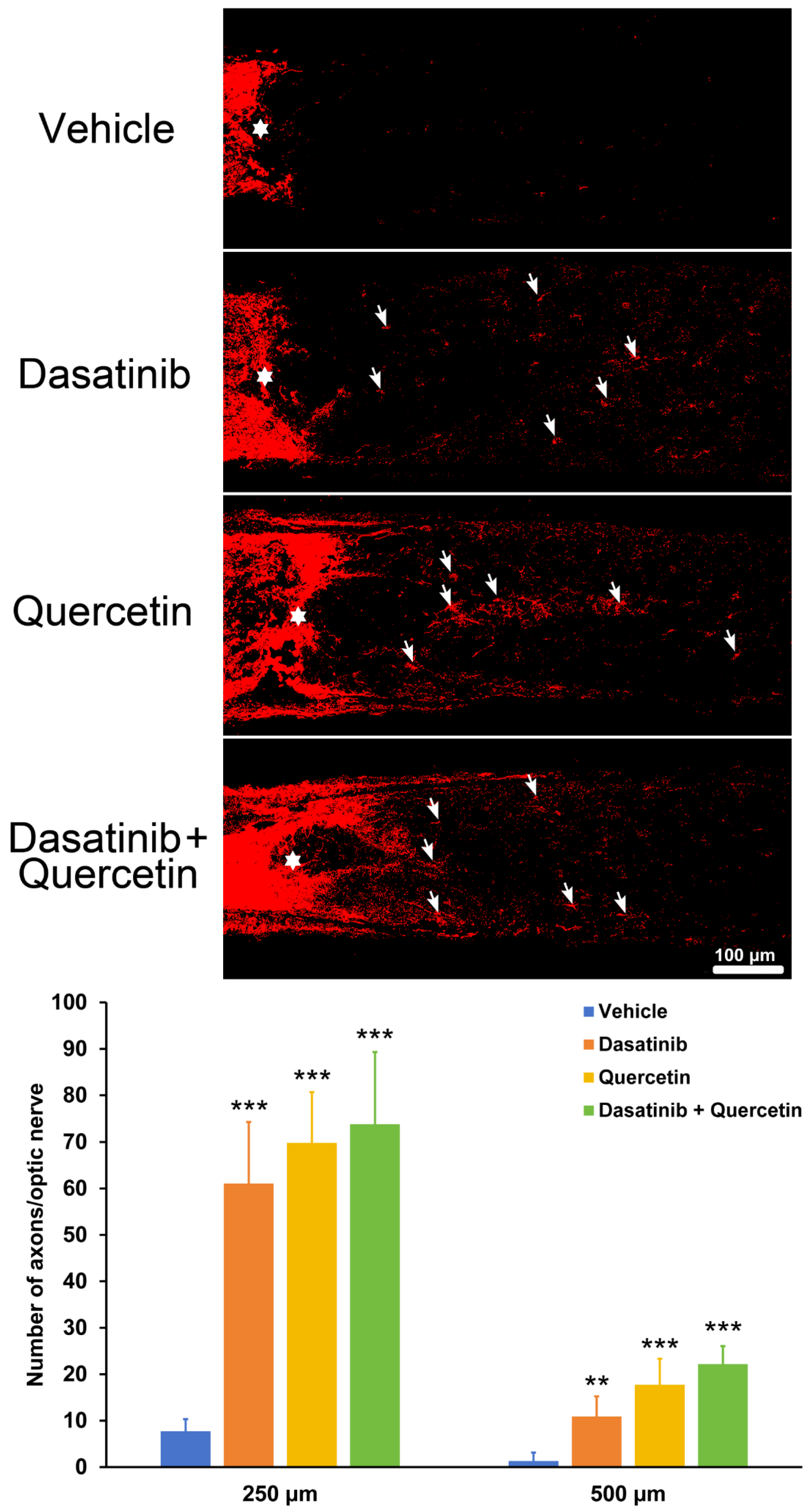

2.2. Dasatinib and Quercetin Treatments Promote Retinal-Ganglion-Cell Axonal Regeneration in Mice Post-Optic Nerve Injury

2.3. Retinal Transcriptomic Analysis of Dasatinib and Quercetin Treatments in Mice Post-Optic Nerve Injury

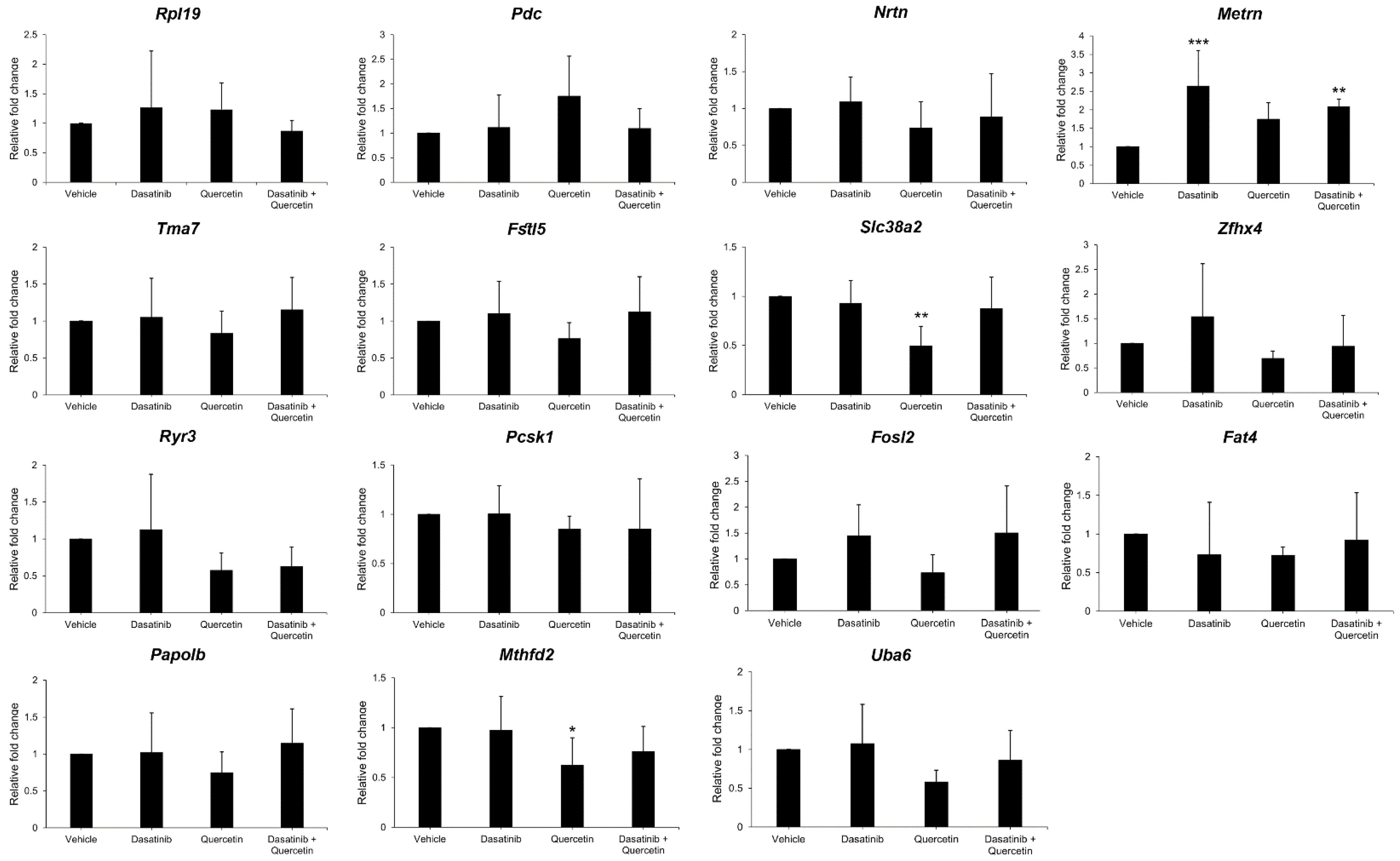

2.4. Validation of Gene Expression in Dasatinib- and Quercetin-Treated Mice Post-Optic Nerve Injury

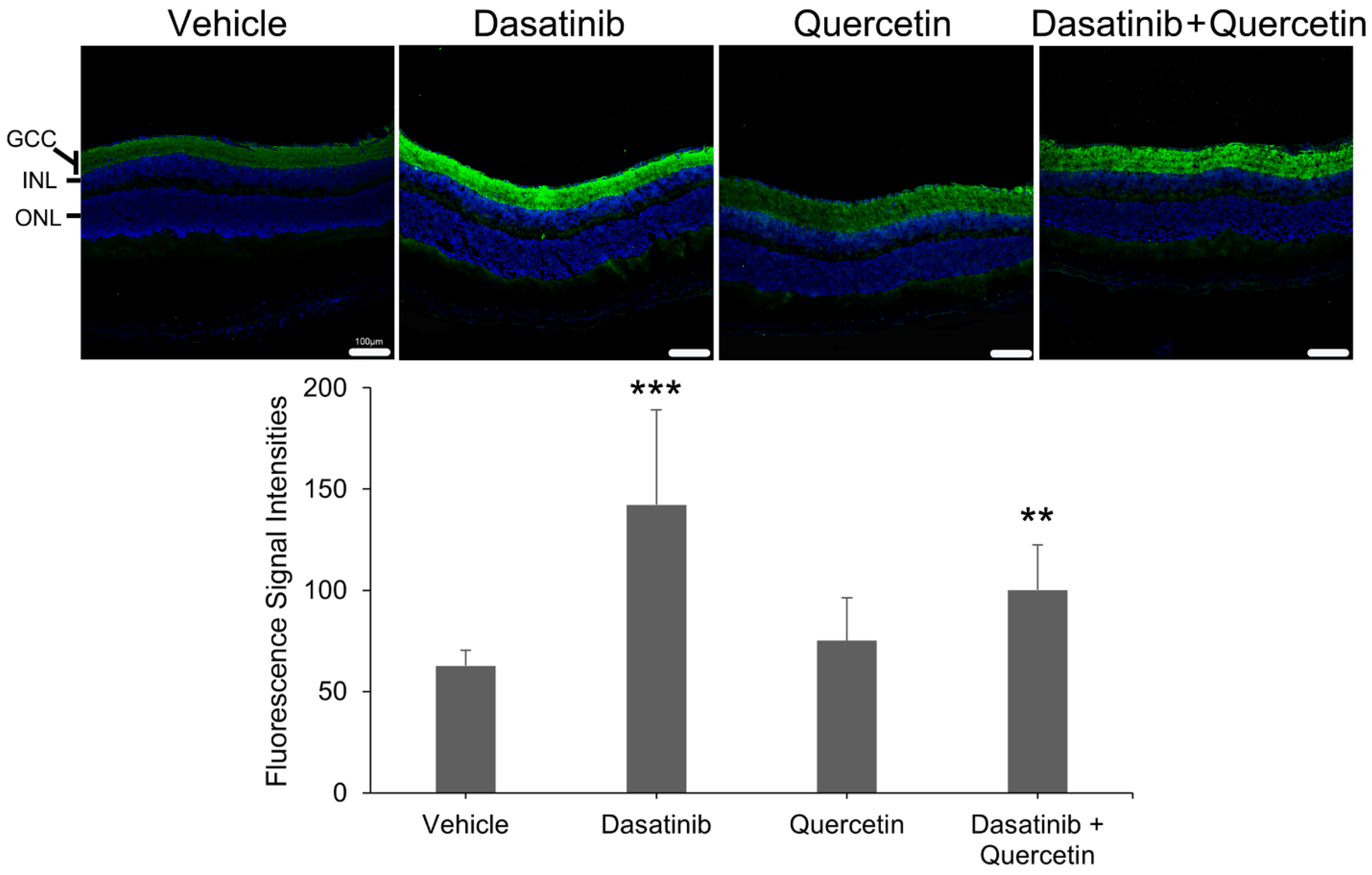

2.5. Expression Analysis of Meteorin in the Retina of Dasatinib- and Quercetin-Treated Mice Post-Optic Nerve Injury

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Optic Nerve Crush Injury

4.3. Treatment of Dasatinib and Quercetin

4.4. Retinal Ganglion Cell Dendrite Analysis

4.5. Retinal Ganglion Cell Axonal Regeneration Analysis

4.6. Retinal Transcriptomic Analysis

4.7. SYBR Green PCR Validation Analysis

4.8. Immunofluorescence Analysis

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tan, S.; Yao, Y.; Yang, Q.; Yuan, X.L.; Cen, L.P.; Ng, T.K. Diversified Treatment Options of Adult Stem Cells for Optic Neuropathies. Cell Transplant. 2022, 31, 9636897221123512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Négrel, A.D.; Thylefors, B. The global impact of eye injuries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1998, 5, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liang, J.J.; Zhuang, X.; Ng, T.K. Longitudinal and simultaneous profiling of 11 modes of cell death in mouse retina post-optic nerve injury. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 222, 109159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, D.L.; Blackmore, M.G.; Hu, Y.; Kaestner, K.H.; Bixby, J.L.; Lemmon, V.P.; Goldberg, J.L. KLF family members regulate intrinsic axon regeneration ability. Science 2009, 326, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Park, K.K.; Belin, S.; Wang, D.; Lu, T.; Chen, G.; Zhang, K.; Yeung, C.; Feng, G.; Yankner, B.A.; et al. Sustained axon regeneration induced by co-deletion of PTEN and SOCS3. Nature 2011, 480, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, K.; Ho, T.S.; Zeng, X.; Turnes, B.L.; Arab, M.; Jayakar, S.; Chen, K.; Kimourtzis, G.; Condro, M.C.; Fazzari, E.; et al. Non-muscle myosin II inhibition at the site of axon injury increases axon regeneration. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Cen, L.P.; Li, Y.; Gilbert, H.Y.; Strelko, O.; Berlinicke, C.; Stavarache, M.A.; Ma, M.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Q.; et al. Monocyte-derived SDF1 supports optic nerve regeneration and alters retinal ganglion cells’ response to Pten deletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2113751119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, L.P.; Ng, T.K.; Liang, J.J.; Zhuang, X.; Yao, X.; Yam, G.H.; Chen, H.; Cheung, H.S.; Zhang, M.; Pang, C.P. Human Periodontal Ligament-Derived Stem Cells Promote Retinal Ganglion Cell Survival and Axon Regeneration After Optic Nerve Injury. Stem Cells 2018, 36, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.L.; Chen, S.L.; Xu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Liang, J.J.; Zhuang, X.; Hald, E.S.; Ng, T.K. Green tea extract enhances retinal ganglion cell survival and axonal regeneration in rats with optic nerve injury. Green tea extract enhances retinal ganglion cell survival and axonal regeneration in rats with optic nerve injury. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 117, 109333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Bin, X.; Chan, K.P.; Chen, S.; Qian, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yuan, X.L.; Qiu, K.; Huang, Y.; et al. Combined treatment of human mesenchymal stem cells and green tea extract on retinal ganglion cell regeneration in rats after optic nerve injury. Exp. Eye Res. 2024, 239, 109787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Bin, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, S.; Yuan, X.L.; Cao, Y.; Ng, T.K. Cellular senescence mediates retinal ganglion cell survival regulation post-optic nerve crush injury. Cell Prolif. 2024, 57, e13719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, L.R.; Nguyen Huu, V.A.; Palomino La Torre, C.; Xu, Q.; Jabari, M.; Krawczyk, M.; Weinreb, R.N.; Skowronska-Krawczyk, D. Early removal of senescent cells protects retinal ganglion cells loss in experimental ocular hypertension. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, S.; Ersan, I.; Karaca, T.; Kara, S.; Gencer, B.; Karaboga, I.; Hasan Ali, T. Quercetin protects the retina by reducing apoptosis due to ischemia-reperfusion injury in a rat model. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2015, 78, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.J.; Zhang, S.H.; Xu, P.; Yang, B.Q.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, X.J.; Huang, W.J.; Wang, M.; Chen, J.Y.; et al. Quercetin Declines Apoptosis, Ameliorates Mitochondrial Function and Improves Retinal Ganglion Cell Survival and Function in In Vivo Model of Glaucoma in Rat and Retinal Ganglion Cell Culture In Vitro. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Tchkonia, T.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Gower, A.C.; Ding, H.; Giorgadze, N.; Palmer, A.K.; Ikeno, Y.; Hubbard, G.B.; Lenburg, M.; et al. The Achilles’ heel of senescent cells: From transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Farr, J.N.; Weigand, B.M.; Palmer, A.K.; Weivoda, M.M.; Inman, C.L.; Ogrodnik, M.B.; Hachfeld, C.M.; Fraser, D.G.; et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.P.; Tran, C.; Lee, F.Y.; Chen, P.; Norris, D.; Sawyers, C.L. Overriding imatinib resistance with a novel ABL kinase inhibitor. Science 2004, 305, 399–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passi, A.; Yasmin, A.; Jha, R.; Saha, P.; Jindal, S.; Goyal, K. A Comprehensive Overview of Quercetin: Chemistry, Analytical Approaches, Formulations, and Therapeutic Approaches. Phytochem. Anal. 2025, 36, 1857–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, M.M.; Garbarino, V.R.; Kautz, T.F.; Palavicini, J.P.; Lopez-Cruzan, M.; Dehkordi, S.K.; Mathews, J.J.; Zare, H.; Xu, P.; Zhang, B.; et al. Senolytic therapy in mild Alzheimer’s disease: A phase 1 feasibility trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2481–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.W.; Han, R.; He, H.J.; Li, J.; Chen, S.Y.; Gu, Y.; Xie, C. Administration of quercetin improves mitochondria quality control and protects the neurons in 6-OHDA-lesioned Parkinson’s disease models. Aging 2021, 13, 11738–11751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firgany, A.E.L.; Sarhan, N.R. Quercetin mitigates monosodium glutamate-induced excitotoxicity of the spinal cord motoneurons in aged rats via p38 MAPK inhibition. Acta Histochem. 2020, 122, 151554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzystyniak, A.; Wesierska, M.; Petrazzo, G.; Gadecka, A.; Dudkowska, M.; Bielak-Zmijewska, A.; Mosieniak, G.; Figiel, I.; Wlodarczyk, J.; Sikora, E. Combination of dasatinib and quercetin improves cognitive abilities in aged male Wistar rats, alleviates inflammation and changes hippocampal synaptic plasticity and histone H3 methylation profile. Aging 2022, 14, 572–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribierre, T.; Bacq, A.; Donneger, F.; Doladilhe, M.; Maletic, M.; Roussel, D.; Le Roux, I.; Chassoux, F.; Devaux, B.; Adle-Biassette, H.; et al. Targeting pathological cells with senolytic drugs reduces seizures in neurodevelopmental mTOR-related epilepsy. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kang, Y.; Liu, P.; Liu, W.; Chen, W.; Hayashi, T.; Mizuno, K.; Hattori, S.; Fujisaki, H.; Ikejima, T. Combined use of dasatinib and quercetin alleviates overtraining-induced deficits in learning and memory through eliminating senescent cells and reducing apoptotic cells in rat hippocampus. Behav. Brain Res. 2023, 440, 114260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, Y.; Carr, C.; Dhandapani, K.M.; Brann, D.W. Senolytic therapy is neuroprotective and improves functional outcome long-term after traumatic brain injury in mice. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1227705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.M.; Yin, Z.Q.; Zhang, L.Y.; Liao, H. Quercetin promotes neurite growth through enhancing intracellular cAMP level and GAP-43 expression. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2015, 13, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katebi, S.; Esmaeili, A.; Ghaedi, K.; Zarrabi, A. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles combined with NGF and quercetin promote neuronal branching morphogenesis of PC12 cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 2157–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, M.; Wang, M.; Chen, H.; Li, W.; Zhou, X. Quercetin promotes locomotor function recovery and axonal regeneration through induction of autophagy after spinal cord injury. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2021, 48, 1642–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Q.; Dou, Y.; Qu, C.; Xu, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Xian, Y.F.; Lin, Z.X. Quercetin enhances survival and axonal regeneration of motoneurons after spinal root avulsion and reimplantation: Experiments in a rat model of brachial plexus avulsion. Inflamm. Regen. 2022, 42, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Guo, T.; Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Sun, Y. Senolytic Treatment Attenuates Global Ischemic Brain Injury and Enhances Cognitive Recovery by Targeting Mitochondria. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 45, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, H.; Luo, Y.; Wu, H.; Deng, W.; Min, X.; Lao, H.; Xiong, H. Senolytic treatment alleviates cochlear senescence and delays age-related hearing loss in C57BL/6J mice. Phytomedicine 2025, 142, 156772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maallem, S.; Mutin, M.; González-González, I.M.; Zafra, F.; Tappaz, M.L. Selective tonicity-induced expression of the neutral amino-acid transporter SNAT2 in oligodendrocytes in rat brain following systemic hypertonicity. Neuroscience 2008, 153, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellsten, S.V.; Tripathi, R.; Ceder, M.M.; Fredriksson, R. Nutritional Stress Induced by Amino Acid Starvation Results in Changes for Slc38 Transporters in Immortalized Hypothalamic Neuronal Cells and Primary Cortex Cells. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Ge, B.; Hudson, T.J.; Rozen, R. Microarray analysis of brain RNA in mice with methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency and hyperhomocysteinemia. Brain Res. Gene Expr. Patterns 2002, 1, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkanen, J.; Landoni, J.C.; Balboa, D.; Haugas, M.; Partanen, J.; Paetau, A.; Isohanni, P.; Brilhante, V.; Suomalainen, A. A complex genomic locus drives mtDNA replicase POLG expression to its disease-related nervous system regions. EMBO Mol. Med. 2018, 10, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, J.; Yamashita, K.; Hashiguchi, H.; Fujii, H.; Shimazaki, T.; Hamada, H. Meteorin: A secreted protein that regulates glial cell differentiation and promotes axonal extension. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 1998–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, J.R.; Emerich, D.F.; Thanos, C.; Thompson, L.H.; Torp, M.; Bintz, B.; Fjord-Larsen, L.; Johansen, T.E.; Wahlberg, L.U. Lentiviral delivery of meteorin protects striatal neurons against excitotoxicity and reverses motor deficits in the quinolinic acid rat model. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011, 41, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Andrade, N.; Torp, M.; Wattananit, S.; Arvidsson, A.; Kokaia, Z.; Jørgensen, J.R.; Lindvall, O. Meteorin is a chemokinetic factor in neuroblast migration and promotes stroke-induced striatal neurogenesis. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012, 32, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.L.; Ermine, C.M.; Jørgensen, J.R.; Parish, C.L.; Thompson, L.H. Over-Expression of Meteorin Drives Gliogenesis Following Striatal Injury. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Zheng, K.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, S.; Liang, J.; Cao, Y.; Ng, T.K.; Qiu, K. Longitudinal in vivo evaluation of retinal ganglion cell complex layer and dendrites in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Exp. Eye Res. 2023, 237, 109708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longair, M.H.; Baker, D.A.; Armstrong, J.D. Simple Neurite Tracer: Open source software for reconstruction, visualization and analysis of neuronal processes. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2453–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, T.A.; Blackman, A.V.; Oyrer, J.; Jayabal, S.; Chung, A.J.; Watt, A.J.; Sjöström, P.J.; van Meyel, D.J. Neuronal morphometry directly from bitmap images. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 982–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.Y.; Bin, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhou, S.; Chen, S.; Cao, Y.; Qiu, K.; Ng, T.K. The Profile of Retinal Ganglion Cell Death and Cellular Senescence in Mice with Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genes | Average FPKM (Dasatinib and Quercetin) | Average FPKM (Vehicle) | log2 Fold Change | padj |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rpl19 | 131.89 | 42.88 | 1.62 | 2.18 × 10−4 |

| Pdc | 86,158.36 | 34,833.44 | 1.31 | 4.84 × 10−13 |

| Nrtn | 471.31 | 201.29 | 1.23 | 6.27 × 10−4 |

| Metrn | 116.95 | 55.10 | 1.09 | 0.042 |

| Tma7 | 2652.60 | 1300.35 | 1.03 | 1.86 × 10−6 |

| Fstl5 | 432.41 | 868.10 | −1.01 | 0.010 |

| Uba6 | 162.91 | 327.84 | −1.01 | 6.34 × 10−4 |

| Slc38a2 | 817.78 | 1690.88 | −1.05 | 6.93 × 10−5 |

| Zfhx4 | 201.65 | 418.33 | −1.05 | 8.45 × 10−4 |

| Ryr3 | 67.32 | 139.93 | −1.06 | 0.024 |

| Pcsk1 | 90.03 | 190.38 | −1.09 | 0.022 |

| Fosl2 | 118.21 | 255.20 | −1.11 | 0.018 |

| Fat4 | 87.83 | 193.34 | −1.14 | 0.004 |

| Papolb | 50.46 | 111.78 | −1.15 | 0.018 |

| Mthfd2 | 155.78 | 406.21 | −1.38 | 0.002 |

| Functional Annotations | Genes | % | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response to glucocorticoid | Pcsk1, Fosl2 | 13.33 | 0.027 |

| Calcium ion binding | Fstl5, Fat4, Ryr3 | 20.00 | 0.041 |

| Cerebral cortex development | Fat4, Slc38a2 | 13.33 | 0.043 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bin, X.; Zhou, S.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, S.; Yao, W.; Cao, Y.; Qiu, K.; Ng, T.K. Dasatinib and Quercetin Alleviate Retinal Ganglion Cell Dendritic Shrinkage and Promote Axonal Regeneration in Mice with Optic Nerve Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412170

Bin X, Zhou S, Xu Y, Chen S, Chen S, Yao W, Cao Y, Qiu K, Ng TK. Dasatinib and Quercetin Alleviate Retinal Ganglion Cell Dendritic Shrinkage and Promote Axonal Regeneration in Mice with Optic Nerve Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412170

Chicago/Turabian StyleBin, Xin, Shuyi Zhou, Yanxuan Xu, Si Chen, Shaowan Chen, Wen Yao, Yingjie Cao, Kunliang Qiu, and Tsz Kin Ng. 2025. "Dasatinib and Quercetin Alleviate Retinal Ganglion Cell Dendritic Shrinkage and Promote Axonal Regeneration in Mice with Optic Nerve Injury" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412170

APA StyleBin, X., Zhou, S., Xu, Y., Chen, S., Chen, S., Yao, W., Cao, Y., Qiu, K., & Ng, T. K. (2025). Dasatinib and Quercetin Alleviate Retinal Ganglion Cell Dendritic Shrinkage and Promote Axonal Regeneration in Mice with Optic Nerve Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412170