Gut–Brain Axis and Bile Acid Signaling: Linking Microbial Metabolism to Brain Function and Metabolic Regulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

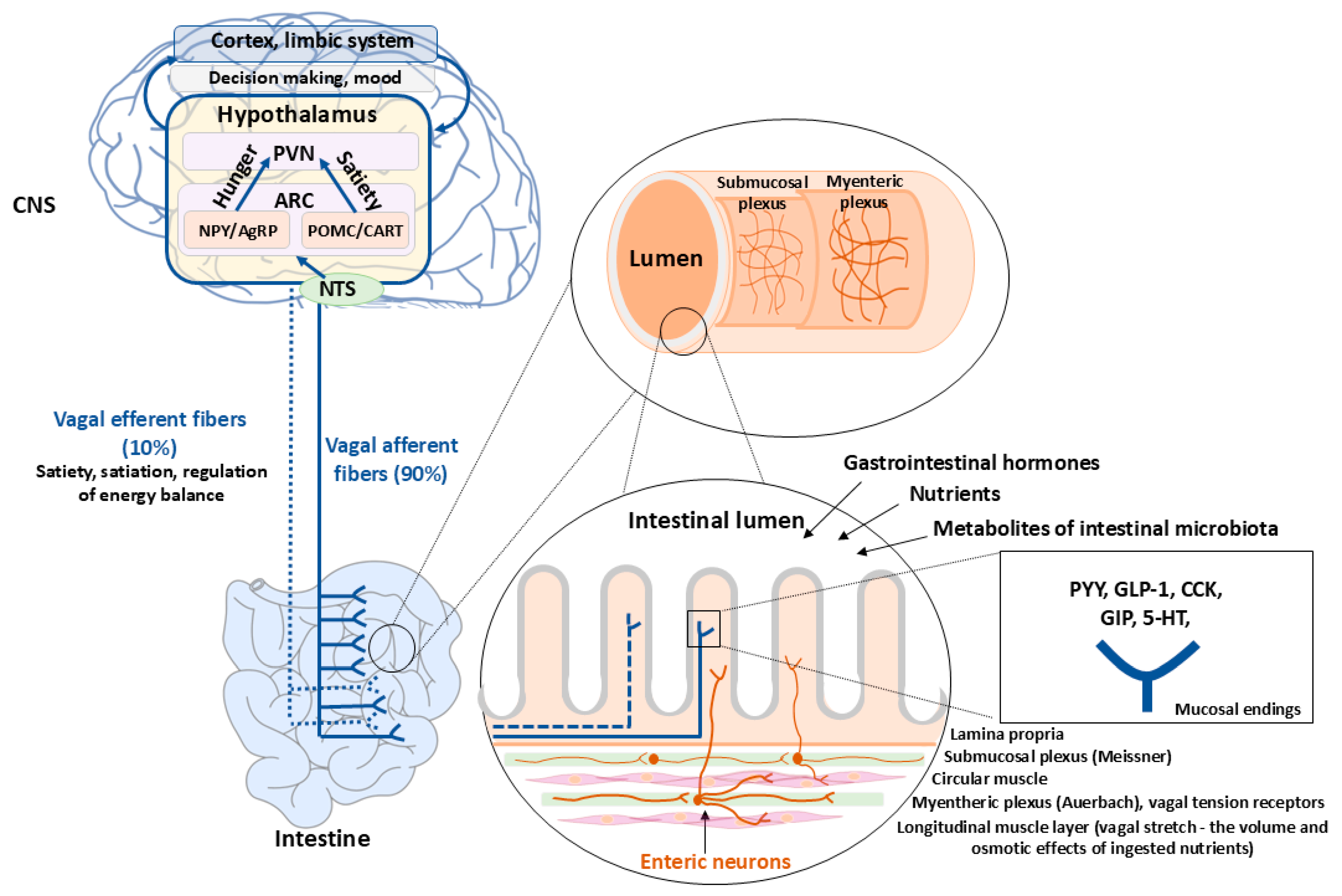

2. The Gut–Brain Signaling Axis

3. Neural Pathways Between Gut and Brain

4. Enteroendocrine Cell Signaling

5. Bile Acid Metabolism in the CNS

5.1. Bile Acids and Blood–Brain Barrier

5.2. Bile Acid Synthesis in the Brain

6. Direct and Indirect Bile Acid Signaling in the CNS

6.1. Direct Bile Acid Signaling in the Brain and the Regulation of Energy Homeostasis

| Receptor (Type) | Major Distribution Cell Types (Human/Rodent) | Canonical Signaling Pathway | Key Physiological Processes Regulated (Examples) | How Bile Acid Composition Modulates Receptor Signaling | Key Endocrine/Immune Mediators Relevant for Gut–brain Signaling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FXR (Farnesoid X receptor)—nuclear receptor | Hepatocytes; ileal enterocytes (incl. some L-cells); cholangiocytes; adipose tissue; kidney; immune cells (macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells); low-moderate expression in hypothalamus and other brain regions [72,82,111,112]. | Ligand (bile acid)-activated nuclear receptor → heterodimer with RXR → transcriptional regulation of SHP, CYP7A1/CYP8B1, bile acid transporters (BSEP, NTCP, OSTα/β), lipogenesis and gluconeogenesis genes; in ileum induces synthesis of enterokine FGF19/FGF15 [82,112]. | Bile acid homeostasis (negative feedback on bile acid synthesis); glucose metabolism (hepatic gluconeogenesis, insulin sensitivity); lipid metabolism (tiacylglycerols, cholesterol); appetite and energy balance via FXR-FGF19-hypothalamus axis; immune modulation (innate and adaptive immune cell function) [111,112,113]. | Potently activated by CDCA and other primary, relatively hydrophobic bile acids; murine muricholic acids (MCA) act as FXR antagonists, causing interspecies differences. Increased conversion to secondary bile acids (DCA, LCA) reduces FXR agonist activity and shifts signaling toward TGR5; conjugation with glycine or taurine reduces FXR agonistic activity, local pH also modulates bile acids’ protonation state and indirectly FXR activation in intestine vs. liver [82,114,115]. | FGF19/FGF15 (enterohepatic endocrine loop to liver and, indirectly, CNS); SHP; downstream changes in insulin signaling; FXR activation in immune cells modulates cytokines (↓ TNF-α, IL-1β; ↑ antimicrobial peptides). These endocrine/immune changes indirectly affect CNS inflammation and energy homeostasis [111,112]. |

| TGR5/GPBAR1—membrane GPCR | Enteroendocrine L-cells (ileum/colon); gallbladder epithelium; brown and white adipocytes; skeletal muscle; cholangiocytes; macrophages and other immune cells; nodose ganglion/vagal afferents; neurons and astrocytes in hippocampus, hypothalamus, cortex and spinal cord [68,72,116]. | Gs-coupled GPCR → ↑ cAMP → PKA/CREB, Epac, downstream ion channel modulation; rapid non-genomic effects. In neurons and microglia, modulates excitability and inflammatory signaling [68,117]. | Appetite and satiety via GLP-1 and PYY release and direct hypothalamic actions; energy expenditure and thermogenesis (BAT activation, sympathetic outflow); glucose homeostasis (enhanced incretin effect, improved insulin sensitivity); neuroinflammation and neuroprotection (reduced microglial activation, improved synaptic plasticity; roles in neuropathic pain, depression and neurodegeneration) [68,116,118,119] | Highest affinity for secondary, hydrophobic BA (LCA ≈ DCA >> CDCA/CA); thus microbial 7α-dehydroxylation that expands DCA/LCA pool biases signaling toward TGR5. Conjugation reduces membrane permeability but TGR5 is located basolaterally, so conjugated bile acids can still activate it after absorption. Changes in bile acid pool hydrophobicity (diet, microbiota, cholestasis, bariatric surgery) therefore strongly influence TGR5-dependent GLP-1 release, thermogenesis and anti-inflammatory effects [113,116,120]. | GLP-1, PYY, OXM from L-cells (gut–brain endocrine loop); catecholamine/sympathetic outputs (BAT); anti-inflammatory cytokines (↑ IL-10, ↓ TNF-α/IL-1β) in macrophages/microglia. These mediators link intestinal TGR5 activation to CNS effects on appetite, mood, neuroinflammation and cardiovascular regulation [68,116,121]. |

| PXR (Pregnane X receptor, NR1I2)—nuclear receptor | Hepatocytes; enterocytes; some brain endothelial cells and neurons (emerging data); immune cells [111,120,122]. | Ligand-activated nuclear receptor that regulates xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4), transporters (MDR1, OATP), and interacts with NF-κB and other inflammatory pathways [111,120]. | Detoxification and xenobiotic clearance; indirect modulation of bile acid homeostasis (regulation of CYP and transporter expression); immune regulation via suppression of pro-inflammatory signaling; may influence neuroinflammation by controlling CNS exposure to bile acid derivatives and xenobiotics [111,113]. | Several bile acids and oxo-bile acid species can act as weak PXR ligands, but microbial bile acid derivatives and co-metabolites (incl. some secondary bile acid and oxysterols) seem particularly relevant. Changes in bile acid composition and microbiota-derived oxo-bile acids therefore alter PXR activation, which in turn adjusts bile acid detoxification and inflammatory tone [111,113]. | Induction of CYP3A and phase II enzymes; modulation of cytokines via NF-κB signaling; these changes can reduce systemic and CNS inflammation and alter drug/bile acid exposure to the brain [87,111]. |

| VDR (Vitamin D receptor)—nuclear receptor | Intestinal epithelium; innate and adaptive immune cells; neurons (cortex, amygdala, caudate putamen, and hypothalamus) [72,111,123]. | Vitamin-D-responsive nuclear receptor; regulates genes involved in calcium homeostasis, antimicrobial peptides, and immune modulation; secondary bile acids (LCA) and oxysterol derivatives can weakly interact [72,111,124]. | Immune homeostasis; neuroprotection and neuronal survival; possible contributions to metabolic control via gut-immune axis [72,87,111,125,126]. | LCA its metabolite 3-keto-LCA and LCA amides are the most efficacious bile acid ligands for VDR; bile acid composition that favors these derivatives may subtly modulate VDR-dependent immune and neuroprotective activities [68,111,127,128]. | Induction of antimicrobial peptides, T-regulatory phenotypes, and anti-inflammatory cytokines; these immune mediators indirectly shape gut–brain communication and neuroinflammation [111,120,127,129]. |

| GR (Glucocorticoid receptor)—nuclear receptor modulated by bile acids in cholestasis | Broadly expressed: hypothalamus (CRH neurons), pituitary, adrenal, liver, immune cells; bile acids can access hypothalamus in cholestasis [87,130,131]. | Ligand-activated transcription factor controlling HPA axis genes (CRH, POMC, ACTH, steroidogenic enzymes) and wide metabolic and inflammatory programs. Bile acids can act directly or indirectly to modulate GR activity [65,75,130]. | Stress response and HPA axis; glucose and energy metabolism via cortisol/corticosterone; immune suppression or dysregulation. In cholestasis, aberrant bile acid-GR interaction in hypothalamus contributes to HPA suppression and altered stress/metabolic responses [130,132]. | Pathologically elevated, hydrophobic and conjugated bile acids during cholestasis enter the brain, where they can modulate GR in CRH neurons, suppress CRH expression and down-regulate HPA output. Thus, bile acid pool expansion and altered composition in liver disease directly affect neuroendocrine stress signaling [65,75,87,130]. | HPA axis hormones (CRH, ACTH, cortisol/corticosterone); downstream metabolic and immune mediators. Bile acid-driven GR modulation links hepatic cholestasis and bile acid overload to central stress circuitry and cognitive/affective symptoms [65,75,87,130,133]. |

| S1PR2 (Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2)—GPCR activated by certain BA | Brain microvascular endothelium (BBB); hepatocytes; cholangiocytes; Kupffer cells; neurons and astrocytes in hippocampus and cortex; immune cells [103,134,135]. | G-protein signaling → Rho/ROCK, ERK, AKT and JNK pathways; regulates cytoskeletal dynamics, tight junctions and inflammatory gene expression [82,103,134,136]. | BBB integrity and vascular permeability; neuroinflammation (microglial activation, leukocyte recruitment); liver and systemic inflammation; contributes to encephalopathy and neurodegeneration in cholestatic states [103,134,137,138,139]. | Certain conjugated bile acids (e.g., taurocholate, taurolithocholate) can act as agonists of S1PR2, especially when their circulating levels are elevated in cholestasis, leading to Rac1-dependent occludin phosphorylation and BBB leakiness. Thus, bile acid pool shifts toward conjugated, hydrophobic species in liver disease drive S1PR2-mediated barrier disruption and CNS inflammation [103,137,139]. | Pro-inflammatory mediators: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6; chemokines and MMP-9 that promote leukocyte infiltration; microglial activation. These immune mediators couple S1PR2 activation by bile acids to neuroinflammation and cognitive/behavioral changes [103,137,139]. |

6.2. Indirect Bile Acid Signaling to the CNS via the FXR-FGF 15/19 Pathway

6.3. Bile Acid Signaling to the CNS via the TGR5-GLP-1 Pathway

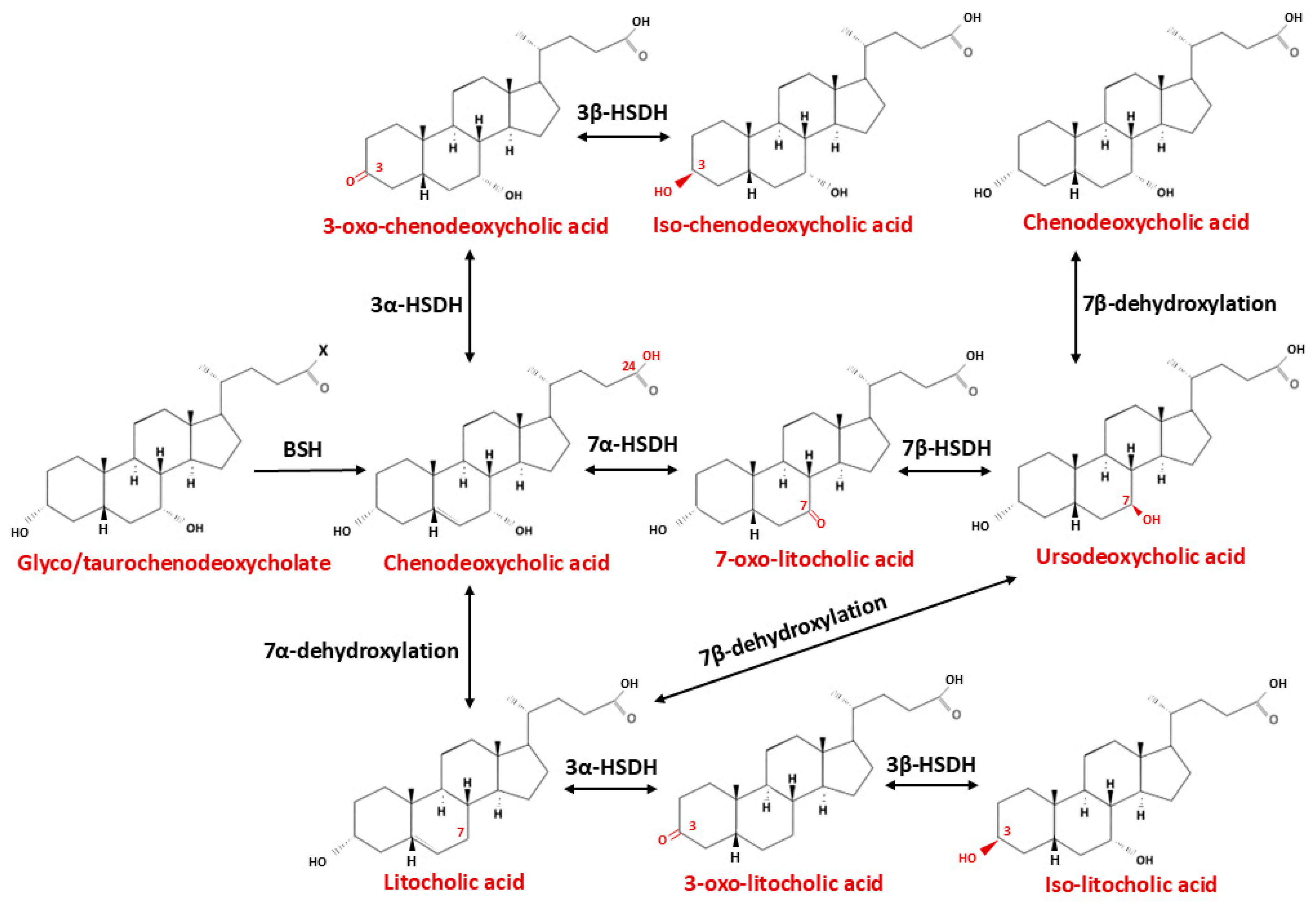

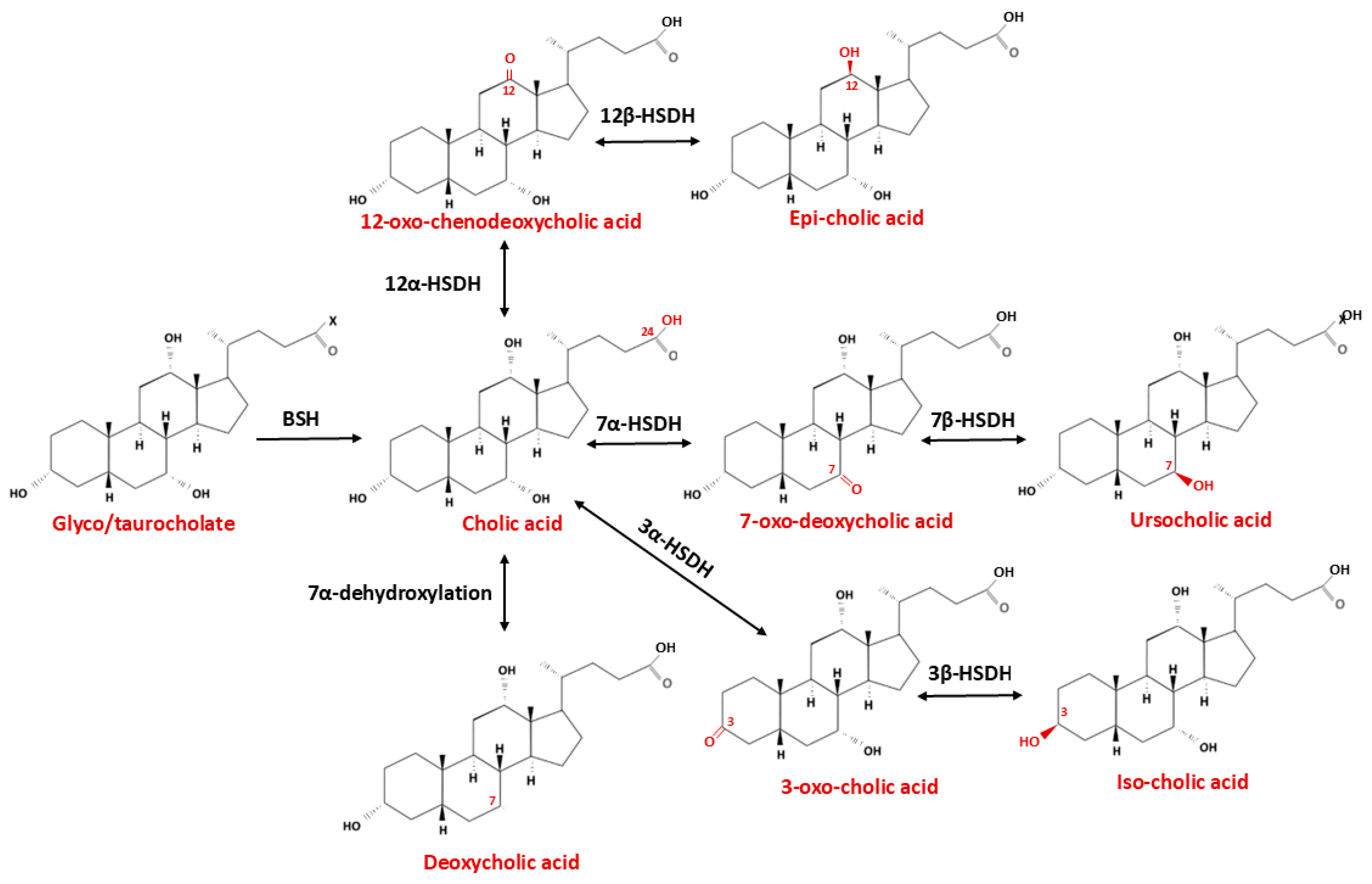

| Type of Modification | Enzyme Catalyzing Biotransformation Reaction | Bacteria | Site of Action | Reaction | Product | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deconjugation | Bile salt hydrolase (BSH) | Actinobacteria, Turicibacter, Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Parabacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Clostridium, Enterococcus, Listeria, Stenotrophomonas, Brucella | C24 | -COO-Gly/Tau-COOH | Tauro/Glyco CA → CA Tauro/Glyco CDCA → CDCA | [173,174,175] |

| Dehydroxylation | bai operon | Clostridium, Eubacterium, Lachnospiraceae, Ruminicoccaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae | C7 | -OH → -H | CA → DCA CDCA → LCA CDCA → UDCA → LCA | [176,177] |

| Oxidation and epimerization | 3 α/β Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | Parabacteroides merdae, Odoribacteriaceae, Ruminococcus gnavus, Blautia producta, Eggerthella genus, Enterorhabdus mucosicola, Acinetobacter lwoffii | C3 | α/β-OH ↔ =O | CA → 3-oxo-CA → Iso-CA CDCA → 3-oxo-CDCA → Iso-CDCA LCA → 3-oxo-LCA → Iso-LCA | [178,179,180] |

| 7 α/β Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | Clostridium baratii Ruminococcus gnavus, Clostridium absonum, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Collinsella aerofaciens | C7 | α/β-OH ↔ =O | CDCA → 7-oxo-LCA → UDCA CA → 7-oxo-DCA → UCA | [181,182] | |

| 12 α/β Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | Eggerthella lenta, Enterorhabdus mucosicola, Clostridium scindens, Peptacetopacter hiranonis, Clostridium hylemonae, Bacteroides, Clostridium paraputrificium, Clostridium tertium, Clostridium difficile | C12 | α/β-OH ↔ =O | CA → 12-oxo-CDCA → epi-CA | [82,183,184] |

7. Intestinal Microbiota–Enteroendocrine/Enterochromaffin Cell Axis

| Metabolite Class (Examples) | Predominant Microbial Sources/Enzymes | Effect on Bile Acid Metabolism and Pool Composition | Mechanism Altering Bile Acid Signaling (Receptors/Pathways) | Impact on CNS/Metabolic/Disease Processes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (acetate, propionate, butyrate) | Produced by Firmicutes (e.g., Faecalibacterium, Roseburia), Bacteroidetes, via fermentation of dietary fibers and resistant starch. | Indirectly modulate bile acid synthesis by regulating hepatic cholesterol metabolism and FXR-FGF19 axis; can influence bile acid pool size and proportion of conjugated vs. unconjugated bile acids through effects on hepatic and intestinal gene expression; may change microbiota composition favoring/de-favoring bile acid-transforming taxa | Activate FFAR2/FFAR3 on enteroendocrine L cells, enhancing GLP-1/PYY secretion and thereby crosstalking with bile acid-TGR5-FXR signaling; SCFAs also modulate intestinal barrier and systemic inflammation, which impact BA receptor sensitivity, epigenetic effects (HDAC inhibition) alter host gene expression (including bile acid synthesis genes); indirectly upregulate TGR5/FXR expression in gut. | Improve glucose homeostasis, insulin sensitivity and body weight in preclinical and human studies; SCFA–EEC signaling contributes to gut–brain regulation of appetite and may influence neuroinflammation and cognitive function via GLP-1 and vagal pathways. | [157,214,225,226,227,228] |

| BSH-mediated deconjugation products (unconjugated primary BA) | Gut bacteria expressing bile salt hydrolase (BSH) (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Clostridium). | Hydrolyze glycine/taurine-conjugated bile acids to free bile acid species, increasing hydrophobicity and availability for further microbial transformations (e.g., 7α-dehydroxylation); reshape ratio of conjugated/unconjugated bile acids in ileum and colon. | Deconjugation alters affinity for FXR and TGR5 (unconjugated species often more hydrophobic, with different receptor potency); changes intestinal FXR tone and downstream FGF19 signaling; modifies bile acids reabsorption kinetics. | Implicated in modulation of MASLD/MASH, cholesterol homeostasis and glucose metabolism; BSH-active probiotics can lower cholesterol and alter bile acid signaling; altered BSH profiles associate with metabolic syndrome and chronic liver disease; may modulate BBB permeability indirectly via bile acid species shifts. | [229,230,231,232] |

| 7α-dehydroxylation products (secondary BA) (deoxycholic acid, DCA; lithocholic acid, LCA) | Low-abundance 7α-dehydroxylating Clostridia (e.g., Clostridium scindens), expressing bai gene cluster (BaiA–BaiI). | Convert primary bile acids (CA, CDCA) to hydrophobic secondary bile acids (DCA, LCA), substantially increasing the fraction of potent TGR5 agonists and altering the primary/secondary bile acids ratio. | DCA and LCA are high-affinity TGR5 ligands and can also modulate FXR; enhanced 7α-dehydroxylation shifts signaling from ileal FXR-FGF19 toward TGR5 in intestine, adipose tissue and possibly CNS; increased hydrophobic bile acids may cross BBB more readily, affecting neuroinflammation. | Support GLP-1-mediated improvement in energy expenditure and glucose metabolism, but excess hydrophobic bile acids are associated with mucosal injury, colon cancer risk and liver injury; recent studies links 7α-dehydroxylating strains to mucosal healing and bile acid homeostasis in colitis. | [155,233,234,235] |

| Microbially conjugated bile acids (microbial bile acid amides MABAs) (e.g., Phe-CA, Leu-CA, Trp-CA) | Diverse human gut microbiota re-conjugating bile acids with amino acids (phenylalanine, leucine, tyrosine, tryptophan, branched-chain and non-proteinogenic amino acids). | Generate novel bile acid species (MABAs) with distinct hydrophobicity and receptor affinity; expand bile acid chemical repertoire beyond classical taurine/glycine conjugates; some species are enriched or depleted in metabolic disease (e.g., Trp-CA ↓ in T2D). | Several MABAs directly activate TGR5 and both intestinal and hepatic FXR isoforms, thereby modulating GLP-1 secretion, FGF19 signaling and hepatic bile acid synthesis; specific conjugates (e.g., Trp-CA) improve glucose tolerance in vivo. | Altered MABA profiles correlate with T2D, obesity and inflammatory bowel disease; experimental data indicate improved glucose homeostasis and reduced adiposity with specific MABAs; potential to modulate gut–brain signaling via GLP-1 and FGF19. | [236,237,238,239,240,241] |

| Hydroxylated and oxidized bile acid species (e.g., 6α-hydroxylated bile acids, oxo-bile acids) | Formation influenced by diet-responsive microbiota and host–microbial enzymes (hydroxylases, dehydrogenases); fiber-enriched microbiota can increase 6α-hydroxylated bile acids. | Modify bile acid pool toward more hydrophilic species with selective receptor profiles; 6α-hydroxylated bile acids partially replace classical secondary bile acids in response to prebiotic/fiber interventions. | 6α-hydroxylated bile acids are potent TGR5 agonists that enhance GLP-1 release and energy expenditure; some oxo-bile acids act as partial FXR agonists/antagonists, fine-tuning FXR signaling in intestine and liver. | In murine models, 6α-hydroxylated bile acids improve glucose metabolism and body weight via TGR5; observational data suggest links between altered hydroxylated bile acid profiles, insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk; potential indirect effects on CNS through improved metabolic control and reduced inflammation. | [242,243,244,245,246] |

| Tryptophan metabolites (indoles: IPA, IAA, IAld) | Lactobacillus, Clostridium, Peptostreptococcus, Bacteroides | Do not directly change bile acid chemical structures but modulate host inflammation and barrier function, thereby altering microbiota composition and downstream bile acid transformations (indirect reshaping). | Activate AhR and PXR in intestinal and immune cells → strengthen barrier, modulate CYP-mediated bile acid metabolism; reduce inflammation that otherwise perturbs bile acid processing. | Improve barrier integrity, reduce intestinal inflammation, indirectly favor beneficial bile acid profiles; implicated in MASLD, metabolic disease and neuroimmune regulation. | [247,248,249] |

| Integrated microbiota– bile acid metabolite networks (SCFAs, secondary BA, indoles) | Complex consortia of gut microbes producing SCFAs, secondary bile acids and tryptophan-derived indoles. | Coordinate regulation of bile acid synthesis, conjugation and transformation; shape bile acid pool composition and distribution along the intestine. | SCFAs → FFAR2/3; secondary bile acids and MABAs → FXR/TGR5; indoles → AhR and intestinal barrier regulation; combined effects converge on GLP-1, FGF19, inflammatory cytokines and vagal signaling, integrating metabolic and gut–brain pathways | Dysregulated metabolite networks are associated with obesity, T2D, MASLD/MASH, IBD and neuropsychiatric/neurodegenerative disorders; balanced profiles correlate with healthier metabolic and cognitive phenotypes and preserved gut–brain homeostasis. | [225,250,251,252,253] |

8. Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis in Neurodegeneration

9. Summary of Clinical Evidence

| Therapeutic Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Impact on Bile Acid Metabolism/Receptors (FXR, TGR5) | Evidence (Preclinical/Clinical) | CNS and Metabolic Effects | Challenges and Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotics | Modulate gut microbiota composition, enhance bile salt hydrolase activity, increase conversion of primary to secondary bile acids, reduce intestinal inflammation. | Indirectly modulates FXR and TGR5 by altering bile acid pool composition. | Animal models show improved lipid/glucose metabolism; small clinical trials in metabolic syndrome and liver diseases. | Preclinical data show reduced neuroinflammation and improved cognition via microbiota–BA–TGR5 signaling; may affect vagal activation, mood and stress responses. Potential regulation of appetite, satiety, and energy homeostasis via gut–brain axis; may influence vagal signaling. | Strain-specific effects; inter-individual variability; long-term efficacy unclear. | [178,283,284,285,286] |

| Prebiotics | Non-digestible fibers promote growth of beneficial microbes that metabolize bile acids, increase SCFA production, modulate gut pH, and reduce bile acids toxicity. | Indirect modulation of FXR/TGR5 through SCFA-mediated signaling. | Preclinical studies and limited clinical data show improved bile acid signaling and metabolic outcomes. | SCFA influence CNS via vagus nerve and enteroendocrine signaling, potentially affecting glucose homeostasis and appetite. SCFA-mediated enteroendocrine and vagal modulation may reduce CNS inflammation and enhance cognitive flexibility and appetite regulation. | Dose-dependent effects; specificity of prebiotic type; potential gastrointestinal side effects. | [287,288,289,290,291] |

| FXR Agonists (e.g., OCA, INT-747) | Activate FXR in liver and intestine; downregulate bile acid synthesis, upregulate transporters (BSEP, OSTα/β), reduce inflammation, regulate lipid/glucose metabolism. enhances insulin sensitivity. | Direct activation of FXR; suppresses CYP7A1; alters hepatic and intestinal bile acid pool. | Preclinical studies; early-phase clinical trials. | May influence CNS-mediated energy balance; indirectly improves glucose/lipid metabolism. Indirect CNS benefits by lowering systemic inflammation and bile acid-driven barrier dysfunction; FXR–FGF19 axis influences hypothalamic energy regulation and neuroinflammatory pathways. | Long-term safety unknown; limited receptor specificity; systemic effects possible. | [91,269,277,292,293,294] |

| FXR Antagonists | Block FXR signaling; increase hepatic bile acid synthesis and intestinal bile acid excretion, may enhance secondary bile acid production. | Decreased FXR-mediated repression of CYP7A1; modifies bile acids pool. | Mostly preclinical studies; limited human data. | Potential indirect effects on CNS and metabolism; research ongoing. | Risk of cholestasis; metabolic effects not fully characterized. | [295,296,297] |

| TGR5 Agonists (e.g., INT-777, betulinic acid, taurolithocholic acid) | Activate TGR5 on enteroendocrine cells; increase GLP-1 and PYY secretion, enhance energy expenditure, modulate bile acid signaling, reduce neuroinflammation, suppress hypothalamic neurons. | Direct TGR5 activation; enhances bile acid-mediated signaling in intestine and liver. | Preclinical studies; early clinical trials. | Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects via microglial TGR5 activation; potential benefits in neurodegenerative disease models. Improves glucose homeostasis, influences appetite via CNS gut–brain axis, potential therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. | Bioavailability and tissue specificity; potential cardiovascular effects. | [99,293,298,299,300] |

| TGR5 Antagonists | Inhibit TGR5 signaling; reduce GLP-1 secretion and energy expenditure, may attenuate bile acid-mediated metabolic effects. | Blocks TGR5-mediated GLP-1 release; modifies bile acid signaling. | Preclinical studies. | Potential therapeutic effect in polycystic liver disease; CNS effects unclear. | Limited human data; potential adverse impact on glucose metabolism; off-target effects possible. | [116,301] |

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation | Transfers gut microbiota from healthy donors to recipients; restores microbial diversity, enhances bile acid metabolism, increases secondary bile acid production, modulates intestinal FXR/TGR5 signaling. | Alters bile acid pool composition; indirect modulation of FXR/TGR5 signaling. | Preclinical and clinical studies in metabolic syndrome, NAFLD, and IBD show improvement in bile acid profiles and metabolic parameters. | May improve CNS-regulated energy balance and metabolic outcomes via gut–brain axis. | Donor variability; safety concerns (infection risk); long-term efficacy uncertain. | [203,302,303,304] |

| TUDCA/UDCA (bile acid analogs) | Anti-oxidative and cytoprotective properties, anti-apoptotic activity, mitochondrial stabilization. | Improves bile acid homeostasis and reduces hydrophobic bile acid toxicity. | Clinical in ALS (TUDCA); preclinical in AD/PD models. | Robust neuroprotection in preclinical models: prevention of microglial activation, improved cognitive outcomes; ongoing clinical evaluation in ALS (TUDCA). | Variable CNS penetration; dose optimization needed. | [305,306,307] |

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The gut-brain axis: Interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, E.S.; Whiteside, E. The Gut-Brain Axis, the Human Gut Microbiota and Their Integration in the Development of Obesity. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarević, S.; Đanic, M.; Al-Salami, H.; Mooranian, A.; Mikov, M. Gut Microbiota Metabolism of Azathioprine: A New Hallmark for Personalized Drug-Targeted Therapy of Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 879170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojančević, M.; Bojić, G.; Salami, H.A.; Mikov, M. The Influence of Intestinal Tract and Probiotics on the Fate of Orally Administered Drugs. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2014, 16, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- ElRakaiby, M.; Dutilh, B.E.; Rizkallah, M.R.; Boleij, A.; Cole, J.N.; Aziz, R.K. Pharmacomicrobiomics: The impact of human microbiome variations on systems pharmacology and personalized therapeutics. Omics 2014, 18, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ðanić, M.; Stanimirov, B.; Pavlović, N.; Goločorbin-Kon, S.; Al-Salami, H.; Stankov, K.; Mikov, M. Pharmacological Applications of Bile Acids and Their Derivatives in the Treatment of Metabolic Syndrome. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Tan, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, D.; Feng, W.; Peng, C. Functions of Gut Microbiota Metabolites, Current Status and Future Perspectives. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 1106–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimirov, B.; Stankov, K.; Mikov, M. Bile acid signaling through farnesoid X and TGR5 receptors in hepatobiliary and intestinal diseases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2015, 14, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojancevic, M.; Stankov, K.; Mikov, M. The impact of farnesoid X receptor activation on intestinal permeability in inflammatory bowel disease. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 26, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangerolamo, L.; Carvalho, M.; Barbosa, H.C.L. The Critical Role of the Bile Acid Receptor TGR5 in Energy Homeostasis: Insights into Physiology and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Pérez, O.; Cruz-Ramón, V.; Chinchilla-López, P.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Bile Acid Metabolism. Ann. Hepatol. 2017, 16, S21–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zheng, I.; Huang, W.; Tang, D.; Zhao, M.; Hou, R.; Huang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wang, S. Research Progress on the Mechanism of Bile Acids and Their Receptors in Depression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, E.A.; Tillisch, K.; Gupta, A. Gut/brain axis and the microbiota. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 926–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhmann, H.; le Roux, C.W.; Bueter, M. The gut-brain axis in obesity. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2014, 28, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaz, B.; Bazin, T.; Pellissier, S. The Vagus Nerve at the Interface of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, S.A.; O’Malley, D. Bile acids, bioactive signalling molecules in interoceptive gut-to-brain communication. J. Physiol. 2022, 600, 2565–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, K.J.; Collins, M.K.; Moloney, G.M.; Knox, E.G.; Aburto, M.R.; Fülling, C.; Morley, S.J.; Clarke, G.; Schellekens, H.; Cryan, J.F. Short chain fatty acids: Microbial metabolites for gut-brain axis signalling. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2022, 546, 111572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, J.M.; Yu, K.; Donaldson, G.P.; Shastri, G.G.; Ann, P.; Ma, L.; Nagler, C.R.; Ismagilov, R.F.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Hsiao, E.Y. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell 2015, 161, 264–276, Erratum in Cell 2015, 163, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, B.S.; Shaito, A.; Motoike, T.; Rey, F.E.; Backhed, F.; Manchester, J.K.; Hammer, R.E.; Williams, S.C.; Crowley, J.; Yanagisawa, M.; et al. Effects of the gut microbiota on host adiposity are modulated by the short-chain fatty-acid binding G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr41. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16767–16772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goehler, L.E.; Gaykema, R.P.; Opitz, N.; Reddaway, R.; Badr, N.; Lyte, M. Activation in vagal afferents and central autonomic pathways: Early responses to intestinal infection with Campylobacter jejuni. Brain Behav. Immun. 2005, 19, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.; Ross, R.P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Stanton, C. γ-Aminobutyric acid production by culturable bacteria from the human intestine. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janik, R.; Thomason, L.A.M.; Stanisz, A.M.; Forsythe, P.; Bienenstock, J.; Stanisz, G.J. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy reveals oral Lactobacillus promotion of increases in brain GABA, N-acetyl aspartate and glutamate. NeuroImage 2016, 125, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, F.; Montanari, C.; Gardini, F.; Tabanelli, G. Biogenic Amine Production by Lactic Acid Bacteria: A Review. Foods 2019, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, Y.; Hiramoto, T.; Nishino, R.; Aiba, Y.; Kimura, T.; Yoshihara, K.; Koga, Y.; Sudo, N. Critical role of gut microbiota in the production of biologically active, free catecholamines in the gut lumen of mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 303, G1288–G1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthoud, H.R.; Kressel, M.; Raybould, H.E.; Neuhuber, W.L. Vagal sensors in the rat duodenal mucosa: Distribution and structure as revealed by in vivo DiI-tracing. Anat. Embryol. 1995, 191, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furness, J.B.; Callaghan, B.P.; Rivera, L.R.; Cho, H.J. The enteric nervous system and gastrointestinal innervation: Integrated local and central control. In Microbial Endocrinology: The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Health and Disease; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 817, pp. 39–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockray, G.J. Enteroendocrine cell signalling via the vagus nerve. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2013, 13, 954–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, A.; Cinci, L.; Rotondo, A.; Serio, R.; Faussone-Pellegrini, M.S.; Vannucchi, M.G.; Mulè, F. Peripheral motor action of glucagon-like peptide-1 through enteric neuronal receptors. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010, 22, 664-e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, L.M.; Zheng, H.; Berthoud, H.R. Vagal afferents innervating the gastrointestinal tract and CCKA-receptor immunoreactivity. Anat. Rec. 2002, 266, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, P.; Parker, H.E.; Adriaenssens, A.E.; Hodgson, J.M.; Cork, S.C.; Trapp, S.; Gribble, F.M.; Reimann, F. Identification and characterization of GLP-1 receptor-expressing cells using a new transgenic mouse model. Diabetes 2014, 63, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelberer, M.M.; Buchanan, K.L.; Klein, M.E.; Barth, B.B.; Montoya, M.M.; Shen, X.; Bohórquez, D.V. A gut-brain neural circuit for nutrient sensory transduction. Science 2018, 361, eaat5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barajon, I.; Serrao, G.; Arnaboldi, F.; Opizzi, E.; Ripamonti, G.; Balsari, A.; Rumio, C. Toll-like receptors 3, 4, and 7 are expressed in the enteric nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2009, 57, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, P.; Giron, M.C.; Qesari, M.; Porzionato, A.; Caputi, V.; Zoppellaro, C.; Banzato, S.; Grillo, A.R.; Spagnol, L.; De Caro, R.; et al. Toll-like receptor 2 regulates intestinal inflammation by controlling integrity of the enteric nervous system. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 1323–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, H.; Ramli, R.; Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Shah, S.; Mullen, P.; Lall, V.; Jones, F.; Shao, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Dorsal root ganglia control nociceptive input to the central nervous system. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3001958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nøhr, M.K.; Egerod, K.L.; Christiansen, S.H.; Gille, A.; Offermanns, S.; Schwartz, T.W.; Møller, M. Expression of the short chain fatty acid receptor GPR41/FFAR3 in autonomic and somatic sensory ganglia. Neuroscience 2015, 290, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaki, S.; Mitsui, R.; Hayashi, H.; Kato, I.; Sugiya, H.; Iwanaga, T.; Furness, J.B.; Kuwahara, A. Short-chain fatty acid receptor, GPR43, is expressed by enteroendocrine cells and mucosal mast cells in rat intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 2006, 324, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Jayasena, C.N.; Bloom, S.R. Obesity and appetite control. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2012, 2012, 824305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthoud, H.R. Metabolic and hedonic drives in the neural control of appetite: Who is the boss? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2011, 21, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, P.V.; Hamr, S.C.; Duca, F.A. Regulation of energy balance by a gut-brain axis and involvement of the gut microbiota. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, R.D.; Cowley, M.A.; Butler, A.A.; Fan, W.; Marks, D.L.; Low, M.J. The arcuate nucleus as a conduit for diverse signals relevant to energy homeostasis. Int. J. Obes. 2001, 25, S63–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriori, P.J.; Evans, A.E.; Sinnayah, P.; Jobst, E.E.; Tonelli-Lemos, L.; Billes, S.K.; Glavas, M.M.; Grayson, B.E.; Perello, M.; Nillni, E.A.; et al. Diet-induced obesity causes severe but reversible leptin resistance in arcuate melanocortin neurons. Cell Metab. 2007, 5, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, M.A.; Smart, J.L.; Rubinstein, M.; Cerdán, M.G.; Diano, S.; Horvath, T.L.; Cone, R.D.; Low, M.J. Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature 2001, 411, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhate, K.T.; Kokare, D.M.; Singru, P.S.; Subhedar, N.K. Central regulation of feeding behavior during social isolation of rat: Evidence for the role of endogenous CART system. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.J.; Li, J.N.; Nie, Y.Z. Gut hormones in microbiota-gut-brain cross-talk. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, R.; Sternini, C.; De Giorgio, R.; Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B. Enteroendocrine cells: A review of their role in brain-gut communication. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016, 28, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, J.G.; Enriquez, J.R.; Wells, J.M. Enteroendocrine cell differentiation and function in the intestine. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2022, 29, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.R.; Osadchiy, V.; Kalani, A.; Mayer, E.A. The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svendsen, B.; Pedersen, J.; Albrechtsen, N.J.; Hartmann, B.; Toräng, S.; Rehfeld, J.F.; Poulsen, S.S.; Holst, J.J. An analysis of cosecretion and coexpression of gut hormones from male rat proximal and distal small intestine. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesch, S.; Rüegg, C.; Fischer, B.; Degen, L.; Beglinger, C. Effect of gastric distension prior to eating on food intake and feelings of satiety in humans. Physiol. Behav. 2006, 87, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, T.D.; Finan, B.; Bloom, S.R.; D’Alessio, D.; Drucker, D.J.; Flatt, P.R.; Fritsche, A.; Gribble, F.; Grill, H.J.; Habener, J.F.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Mol. Metab. 2019, 30, 72–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, S.; Cork, S.C. PPG neurons of the lower brain stem and their role in brain GLP-1 receptor activation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2015, 309, R795–R804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, M.; Willis, J.R.; Dalvi, N.; Fokakis, Z.; Virkus, S.A.; Hardaway, J.A. Integration of Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Actions Through the Central Amygdala. Endocrinology 2025, 166, bqaf019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauck, M.A.; Quast, D.R.; Wefers, J.; Meier, J.J. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes—State-of-the-art. Mol. Metab. 2021, 46, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Purnell, J.Q. The Role of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 in Energy Homeostasis. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2019, 17, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasiou, I.; Argyrakopoulou, G.; Dalamaga, M.; Kokkinos, A. Dual and Triple Gut Peptide Agonists on the Horizon for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity. An Overview of Preclinical and Clinical Data. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhre, R.E.; Wewer Albrechtsen, N.J.; Hartmann, B.; Deacon, C.F.; Holst, J.J. Measurement of the incretin hormones: Glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2015, 29, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredouani, A. GLP-1 receptor agonists, are we witnessing the emergence of a paradigm shift for neuro-cardio-metabolic disorders? Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 269, 108824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüttimann, E.B.; Arnold, M.; Hillebrand, J.J.; Geary, N.; Langhans, W. Intrameal hepatic portal and intraperitoneal infusions of glucagon-like peptide-1 reduce spontaneous meal size in the rat via different mechanisms. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Chen, T.; Zhao, A.; Wang, X.; Xie, G.; Huang, F.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; et al. The Brain Metabolome of Male Rats across the Lifespan. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero, N.; Ruiz, L.; Sánchez, B.; Margolles, A.; Delgado, S. Intestinal Bacteria Interplay With Bile and Cholesterol Metabolism: Implications on Host Physiology. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonne, D.P.; van Nierop, F.S.; Kulik, W.; Soeters, M.R.; Vilsbøll, T.; Knop, F.K. Postprandial Plasma Concentrations of Individual Bile Acids and FGF-19 in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 3002–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, T.; Watanabe, S.; Tomaru, K.; Yamazaki, W.; Yoshizawa, K.; Ogawa, S.; Nagao, H.; Minato, K.; Maekawa, M.; Mano, N. Unconjugated bile acids in rat brain: Analytical method based on LC/ESI-MS/MS with chemical derivatization and estimation of their origin by comparison to serum levels. Steroids 2017, 125, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, M.; McMillin, M.; Galindo, C.; Frampton, G.; Pae, H.Y.; DeMorrow, S. Bile acids permeabilize the blood brain barrier after bile duct ligation in rats via Rac1-dependent mechanisms. Dig. Liver Dis. 2014, 46, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillin, M.; Frampton, G.; Quinn, M.; Divan, A.; Grant, S.; Patel, N.; Newell-Rogers, K.; DeMorrow, S. Suppression of the HPA Axis During Cholestasis Can Be Attributed to Hypothalamic Bile Acid Signaling. Mol. Endocrinol. 2015, 29, 1720–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmela, I.; Correia, L.; Silva, R.F.; Sasaki, H.; Kim, K.S.; Brites, D.; Brito, M.A. Hydrophilic bile acids protect human blood-brain barrier endothelial cells from disruption by unconjugated bilirubin: An in vitro study. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, G.J.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Aranha, M.M.; Hilbert, S.J.; Davey, C.; Kelkar, P.; Low, W.C.; Steer, C.J. Safety, tolerability, and cerebrospinal fluid penetration of ursodeoxycholic Acid in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2010, 33, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ramírez, L.; Mey, J. Emerging Roles of Bile Acids and TGR5 in the Central Nervous System: Molecular Functions and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, M.V.; Kullak-Ublick, G.A.; Hagenbuch, B.; Meier, P.J. Transport of bile acids in hepatic and non-hepatic tissues. J. Exp. Biol. 2001, 204, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillin, M.; Frampton, G.; Quinn, M.; Ashfaq, S.; de los Santos, M., 3rd; Grant, S.; DeMorrow, S. Bile Acid Signaling Is Involved in the Neurological Decline in a Murine Model of Acute Liver Failure. Am. J. Pathol. 2016, 186, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, J.; Adu, J.; Davey, A.J.; Abbott, N.J.; Bradbury, M.W. The effect of bile salts on the permeability and ultrastructure of the perfused, energy-depleted, rat blood-brain barrier. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1991, 11, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.; Huang, X.; Wang, D.; Yu, D.; Hou, S.; Cui, H.; Song, L. Roles of bile acids signaling in neuromodulation under physiological and pathological conditions. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 106, Erratum in Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloni, P.; Funk, C.C.; Yan, J.; Yurkovich, J.T.; Kueider-Paisley, A.; Nho, K.; Heinken, A.; Jia, W.; Mahmoudiandehkordi, S.; Louie, G.; et al. Metabolic Network Analysis Reveals Altered Bile Acid Synthesis and Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Rep. Med. 2020, 1, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, N.; Goto, T.; Uchida, M.; Nishimura, K.; Ando, M.; Kobayashi, N.; Goto, J. Presence of protein-bound unconjugated bile acids in the cytoplasmic fraction of rat brain. J. Lipid Res. 2004, 45, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeilly, A.D.; Macfarlane, D.P.; O’Flaherty, E.; Livingstone, D.E.; Mitić, T.; McConnell, K.M.; McKenzie, S.M.; Davies, E.; Reynolds, R.M.; Thiesson, H.C.; et al. Bile acids modulate glucocorticoid metabolism and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in obstructive jaundice. J. Hepatol. 2010, 52, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loera-Valencia, R.; Vazquez-Juarez, E.; Muñoz, A.; Gerenu, G.; Gómez-Galán, M.; Lindskog, M.; DeFelipe, J.; Cedazo-Minguez, A.; Merino-Serrais, P. High levels of 27-hydroxycholesterol results in synaptic plasticity alterations in the hippocampus. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, M.; Yaguti, H.; Yoshitsugu, H.; Naito, S.; Satoh, T. Tissue distribution of mRNA expression of human cytochrome P450 isoforms assessed by high-sensitivity real-time reverse transcription PCR. Yakugaku Zasshi 2003, 123, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillin, M.; DeMorrow, S. Effects of bile acids on neurological function and disease. Faseb J. 2016, 30, 3658–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, E.G.; Guileyardo, J.M.; Russell, D.W. cDNA cloning of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase, a mediator of cholesterol homeostasis in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 7238–7243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietschy, J.M. Central nervous system: Cholesterol turnover, brain development and neurodegeneration. Biol. Chem. 2009, 390, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertens, K.L.; Kalsbeek, A.; Soeters, M.R.; Eggink, H.M. Bile Acid Signaling Pathways from the Enterohepatic Circulation to the Central Nervous System. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleishman, J.S.; Kumar, S. Bile acid metabolism and signaling in health and disease: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibuya, T.; Sato, A.; Nishimoto-Kusunose, S.; Yoshizawa, K.; Higashi, T. Further evidence for blood-to-brain influx of unconjugated bile acids by passive diffusion: Determination of their brain-to-serum concentration ratios in rats by LC/MS/MS. Steroids 2024, 204, 109397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, J.; Hu, W.; Wang, C.; Lu, X.; Tong, L.; Wu, F.; Zhang, W. Identification of functional farnesoid X receptors in brain neurons. FEBS Lett. 2016, 590, 3233–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, I.; Juneja, K.; Nimmakayala, T.; Bansal, L.; Pulekar, S.; Duggineni, D.; Ghori, H.K.; Modi, N.; Younas, S. Gut Microbiota and Mental Health: A Comprehensive Review of Gut-Brain Interactions in Mood Disorders. Cureus 2025, 17, e81447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.S.; Karimi, G.; Ghanimi, H.A.; Roohbakhsh, A. The potential of CYP46A1 as a novel therapeutic target for neurological disorders: An updated review of mechanisms. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 949, 175726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, X.Y.; Tan, L.Y.; Chae, W.R.; Lee, D.Y.; Lee, Y.A.; Wuestefeld, T.; Jung, S. Liver’s influence on the brain through the action of bile acids. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1123967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qiu, K.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, Y. Metabolic Crosstalk between Liver and Brain: From Diseases to Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlovic, N.; Stanimirov, B.; Mikov, M. Bile Acids as Novel Pharmacological Agents: The Interplay Between Gene Polymorphisms, Epigenetic Factors and Drug Response. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 187–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copple, B.L.; Li, T. Pharmacology of bile acid receptors: Evolution of bile acids from simple detergents to complex signaling molecules. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 104, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wu, J.; Ye, T.; Chen, Z.; Tao, J.; Tong, L.; Ma, K.; Wen, J.; Wang, H.; Huang, C. Farnesoid X Receptor-Mediated Cytoplasmic Translocation of CRTC2 Disrupts CREB-BDNF Signaling in Hippocampal CA1 and Leads to the Development of Depression-Like Behaviors in Mice. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 23, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Wang, T.; Lan, Y.; Yang, L.; Pan, W.; Zhu, Y.; Lv, B.; Wei, Y.; Shi, H.; Wu, H.; et al. Deletion of mouse FXR gene disturbs multiple neurotransmitter systems and alters neurobehavior. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, H.M.; Zang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, R.B.; Shi, X.J.; Mamtilahun, M.; Liu, C.; Luo, L.L.; Tian, X.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Farnesoid X receptor knockout protects brain against ischemic injury through reducing neuronal apoptosis in mice. J. Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggink, H.M.; Tambyrajah, L.L.; van den Berg, R.; Mol, I.M.; van den Heuvel, J.K.; Koehorst, M.; Groen, A.K.; Boelen, A.; Kalsbeek, A.; Romijn, J.A.; et al. Chronic infusion of taurolithocholate into the brain increases fat oxidation in mice. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 236, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckmyn, B.; Domenger, D.; Blondel, C.; Ducastel, S.; Nicolas, E.; Dorchies, E.; Caron, E.; Charton, J.; Vallez, E.; Deprez, B.; et al. Farnesoid X Receptor Activation in Brain Alters Brown Adipose Tissue Function via the Sympathetic System. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 808603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R.; Wu, X.; Yuan, D.; Zhao, J.; Tang, S.; Hong, H.; Long, Y. Activation of TGR5 Ameliorates Streptozotocin-Induced Cognitive Impairment by Modulating Apoptosis, Neurogenesis, and Neuronal Firing. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 3716609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keitel, V.; Görg, B.; Bidmon, H.J.; Zemtsova, I.; Spomer, L.; Zilles, K.; Häussinger, D. The bile acid receptor TGR5 (Gpbar-1) acts as a neurosteroid receptor in brain. Glia 2010, 58, 1794–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillin, M.; Frampton, G.; Tobin, R.; Dusio, G.; Smith, J.; Shin, H.; Newell-Rogers, K.; Grant, S.; DeMorrow, S. TGR5 signaling reduces neuroinflammation during hepatic encephalopathy. J. Neurochem. 2015, 135, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perino, A.; Velázquez-Villegas, L.A.; Bresciani, N.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Q.; Fénelon, V.S.; Castellanos-Jankiewicz, A.; Zizzari, P.; Bruschetta, G.; Jin, S.; et al. Central anorexigenic actions of bile acids are mediated by TGR5. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellanos-Jankiewicz, A.; Guzmán-Quevedo, O.; Fénelon, V.S.; Zizzari, P.; Quarta, C.; Bellocchio, L.; Tailleux, A.; Charton, J.; Fernandois, D.; Henricsson, M.; et al. Hypothalamic bile acid-TGR5 signaling protects from obesity. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1483–1492.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, J.Y.; Lee, A.; Lu, Y.X.; Zhou, S.Y.; Owyang, C. Satiety induced by bile acids is mediated via vagal afferent pathways. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e132400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, A.; Tews, B.; Arzt, M.E.; Weinmann, O.; Obermair, F.J.; Pernet, V.; Zagrebelsky, M.; Delekate, A.; Iobbi, C.; Zemmar, A.; et al. The sphingolipid receptor S1PR2 is a receptor for Nogo-a repressing synaptic plasticity. PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, e1001763, Erratum in PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, e1001818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillin, M.; Frampton, G.; Grant, S.; Khan, S.; Diocares, J.; Petrescu, A.; Wyatt, A.; Kain, J.; Jefferson, B.; DeMorrow, S. Bile Acid-Mediated Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor 2 Signaling Promotes Neuroinflammation during Hepatic Encephalopathy in Mice. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Dai, L.; Mu, J.; Wang, X.; Hong, Y.; Zhu, C.; Jin, L.; Li, S. S1PR2 antagonist alleviates oxidative stress-enhanced brain endothelial permeability by attenuating p38 and Erk1/2-dependent cPLA(2) phosphorylation. Cell. Signal. 2019, 53, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemmen, J.; Tozakidis, I.E.; Galla, H.J. Pregnane X receptor upregulates ABC-transporter Abcg2 and Abcb1 at the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res. 2013, 1491, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyles, D.W.; Smith, S.; Kinobe, R.; Hewison, M.; McGrath, J.J. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1 alpha-hydroxylase in human brain. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2005, 29, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, R.J.; Lee, S.; Ma, L.; Zhang, D.; Schlessinger, J.; Shulman, G.I. FGF1 and FGF19 reverse diabetes by suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raufman, J.P.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, K.; Compadre, C.; Compadre, L.; Zimniak, P. Selective interaction of bile acids with muscarinic receptors: A case of molecular mimicry. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 457, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubring, S.R.; Fleischer, W.; Lin, J.S.; Haas, H.L.; Sergeeva, O.A. The bile steroid chenodeoxycholate is a potent antagonist at NMDA and GABA(A) receptors. Neurosci. Lett. 2012, 506, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedsadr, M.S.; Weinmann, O.; Amorim, A.; Ineichen, B.V.; Egger, M.; Mirnajafi-Zadeh, J.; Becher, B.; Javan, M.; Schwab, M.E. Inactivation of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 (S1PR2) decreases demyelination and enhances remyelination in animal models of multiple sclerosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 124, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.C.P.; Ma, J.; Loiola, R.A.; Chen, X.; Jia, W. Bile acid-activated receptors in innate and adaptive immunity: Targeted drugs and biological agents. Eur. J. Immunol. 2023, 53, e2250299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Yi, Q.; Luo, L.; Xiong, Y. Regulation of bile acids and their receptor FXR in metabolic diseases. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1447878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.Y. Bile acid metabolism and signaling. Compr. Physiol. 2013, 3, 1191–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, H.; Zhang, C.; Bai, Y.; Cao, H.; Che, Q.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. Effect of different bile acids on the intestine through enterohepatic circulation based on FXR. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1949095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Huang, Q.; Chen, T.; Cao, X.; Wen, C.; Shen, X.; Li, J.; et al. A Current Understanding of FXR in NAFLD: The multifaceted regulatory role of FXR and novel lead discovery for drug development. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 175, 116658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, D.; He, J.; He, X. The role of bile acid receptor TGR5 in regulating inflammatory signalling. Scand. J. Immunol. 2024, 99, e13361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, H.; Yu, Q.; Kang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Cheng, F.; Wang, X.; Li, F. Decoding TGR5: A comprehensive review of its impact on cerebral diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 213, 107671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.G.; Yao, Y.; Liang, Y.J.; Lei, J.; Feng, S.Y.; Zhang, Z.X.; Tian, Y.; Cai, J.; Xing, G.G.; Fu, K.Y. Activation of TGR5 in the injured nerve site according to a prevention protocol mitigates partial sciatic nerve ligation-induced neuropathic pain by alleviating neuroinflammation. PAIN 2025, 166, 1296–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Wang, L.; Xie, W.; Chen, E.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Can, D.; Lei, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. TGR5 deficiency in excitatory neurons ameliorates Alzheimer’s pathology by regulating APP processing. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzadilla, N.; Comiskey, S.M.; Dudeja, P.K.; Saksena, S.; Gill, R.K.; Alrefai, W.A. Bile acids as inflammatory mediators and modulators of intestinal permeability. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1021924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonini Cencicchio, M.; Montini, F.; Palmieri, V.; Massimino, L.; Lo Conte, M.; Finardi, A.; Mandelli, A.; Asnicar, F.; Pavlovic, R.; Drago, D.; et al. Microbiota-produced immune regulatory bile acid metabolites control central nervous system autoimmunity. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, C.A.; Koonce, C.J.; Walf, A.A. The pregnane xenobiotic receptor, a prominent liver factor, has actions in the midbrain for neurosteroid synthesis and behavioral/neural plasticity of female rats. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; He, Y.; Beck, J.; da Silva Teixeira, S.; Harrison, K.; Xu, Y.; Sisley, S. Defining vitamin D receptor expression in the brain using a novel VDR(Cre) mouse. J. Comp. Neurol. 2021, 529, 2362–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makishima, M.; Lu, T.T.; Xie, W.; Whitfield, G.K.; Domoto, H.; Evans, R.M.; Haussler, M.R.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. Vitamin D receptor as an intestinal bile acid sensor. Science 2002, 296, 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemulapalli, V.; Shirwaikar Thomas, A. The Role of Vitamin D in Gastrointestinal Homeostasis and Gut Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, H.; Ishizawa, M.; Kodama, M.; Nagase, Y.; Kato, S.; Makishima, M.; Sakurai, K. Vitamin D Receptor Mediates Attenuating Effect of Lithocholic Acid on Dextran Sulfate Sodium Induced Colitis in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pols, T.W.H.; Puchner, T.; Korkmaz, H.I.; Vos, M.; Soeters, M.R.; de Vries, C.J.M. Lithocholic acid controls adaptive immune responses by inhibition of Th1 activation through the Vitamin D receptor. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshihara, A.; Kawasaki, H.; Masuno, H.; Takada, K.; Numoto, N.; Ito, N.; Hirata, N.; Kanda, Y.; Ishizawa, M.; Makishima, M.; et al. Lithocholic Acid Amides as Potent Vitamin D Receptor Agonists. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.; He, J.; Yin, X.; Shi, Y.; Wan, J.; Tian, Z. The protective effect of lithocholic acid on the intestinal epithelial barrier is mediated by the vitamin D receptor via a SIRT1/Nrf2 and NF-κB dependent mechanism in Caco-2 cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2019, 316, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, A.D.; Kain, J.; Liere, V.; Heavener, T.; DeMorrow, S. Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Dysfunction in Cholestatic Liver Disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap, F.G.; Trauner, M.; Jansen, P.L. Bile acid receptors as targets for drug development. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, L.; Simbrunner, B.; Jachs, M.; Wolf, P.; Bauer, D.J.M.; Scheiner, B.; Balcar, L.; Semmler, G.; Schwarz, M.; Marculescu, R.; et al. An impaired pituitary-adrenal signalling axis in stable cirrhosis is linked to worse prognosis. JHEP Rep. 2023, 5, 100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, L.M.V.; Barron-Millar, B.; Leslie, J.; Richardson, C.; Zaki, M.Y.W.; Luli, S.; Burgoyne, R.A.; Cameron, R.I.T.; Smith, G.R.; Brain, J.G.; et al. Anti-Cholestatic Therapy with Obeticholic Acid Improves Short-Term Memory in Bile Duct-Ligated Mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2023, 193, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Han, W.; Jiang, H.; Bi, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, M.; Lin, X.; Liu, Z. Molecular mechanism and therapeutic strategy of bile acids in Alzheimer’s disease from the emerging perspective of the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, G.; Cedeño, R.R.; Casadevall, M.P.; Ramió-Torrentà, L. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate (S1P) and S1P Signaling Pathway Modulators, from Current Insights to Future Perspectives. Cells 2022, 11, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Wang, B.; Wu, X.; Cheng, J.; Ye, J.; Wang, C.; Zhu, H.; Liu, X. How do sphingosine-1-phosphate affect immune cells to resolve inflammation? Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1362459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggeri, A.; Schepers, M.; Tiane, A.; Rombaut, B.; van Veggel, L.; Hellings, N.; Prickaerts, J.; Pittaluga, A.; Vanmierlo, T. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor Modulators and Oligodendroglial Cells: Beyond Immunomodulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Men, Y.; An, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, G.; Wu, Y. Overexpression of endothelial S1pr2 promotes blood-brain barrier disruption via JNK/c-Jun/MMP-9 pathway after traumatic brain injury in both in vivo and in vitro models. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1448570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Cha, L.; Huang, S.Y.; Bai, G.H.; Li, J.H.; Xiong, X.; Feng, Y.X.; Feng, D.P.; Gao, L.; Li, J.Y. Dysregulation of bile acid signal transduction causes neurological dysfunction in cirrhosis rats. World J. Hepatol. 2025, 17, 101340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, P.; Hochrath, K.; Horvath, A.; Chen, P.; Seebauer, C.T.; Llorente, C.; Wang, L.; Alnouti, Y.; Fouts, D.E.; Stärkel, P.; et al. Modulation of the intestinal bile acid/farnesoid X receptor/fibroblast growth factor 15 axis improves alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology 2018, 67, 2150–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorucci, S.; Marchianò, S.; Distrutti, E.; Biagioli, M. Bile acids and their receptors in hepatic immunity. Liver Res. 2025, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadaleta, R.M.; Moschetta, A. Metabolic Messengers: Fibroblast growth factor 15/19. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsuchou, H.; Pan, W.; Kastin, A.J. Fibroblast growth factor 19 entry into brain. Fluids Barriers CNS 2013, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, K.K.; Kohli, R.; Gutierrez-Aguilar, R.; Gaitonde, S.G.; Woods, S.C.; Seeley, R.J. Fibroblast growth factor-19 action in the brain reduces food intake and body weight and improves glucose tolerance in male rats. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Marcelin, G.; Blouet, C.; Jeong, J.H.; Jo, Y.H.; Schwartz, G.J.; Chua, S., Jr. A gut-brain axis regulating glucose metabolism mediated by bile acids and competitive fibroblast growth factor actions at the hypothalamus. Mol. Metab. 2018, 8, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelin, G.; Jo, Y.H.; Li, X.; Schwartz, G.J.; Zhang, Y.; Dun, N.J.; Lyu, R.M.; Blouet, C.; Chang, J.K.; Chua, S., Jr. Central action of FGF19 reduces hypothalamic AGRP/NPY neuron activity and improves glucose metabolism. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhard, G.S.; Styer, A.M.; Wood, G.C.; Roesch, S.L.; Petrick, A.T.; Gabrielsen, J.; Strodel, W.E.; Still, C.D.; Argyropoulos, G. A role for fibroblast growth factor 19 and bile acids in diabetes remission after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1859–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, X.; Phung, V.; Lindhout, D.A.; Mondal, K.; Hsu, J.Y.; Yang, H.; Humphrey, M.; Ding, X.; Arora, T.; et al. Separating Tumorigenicity from Bile Acid Regulatory Activity for Endocrine Hormone FGF19. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 3306–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalqadir, N.; Adeli, K. GLP-1 and GLP-2 Orchestrate Intestine Integrity, Gut Microbiota, and Immune System Crosstalk. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, G.; McRae, A.; Rievaj, J.; Davis, J.; Zandvakili, I.; Linker-Nord, S.; Burton, D.; Roberts, G.; Reimann, F.; Gedulin, B.; et al. Ileo-colonic delivery of conjugated bile acids improves glucose homeostasis via colonic GLP-1-producing enteroendocrine cells in human obesity and diabetes. EBioMedicine 2020, 55, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wang, K.; Jiang, C. Microbiota-derived bile acid metabolic enzymes and their impacts on host health. Cell Insight 2025, 4, 100265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhao, J.; Yang, H.; Ouyang, Z.; Lv, C.; Geng, Z.; Zhao, J. The bile acid-gut microbiota axis: A central hub for physiological regulation and a novel therapeutic target for metabolic diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 188, 118182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, B.; Collins, S.L.; Tanes, C.E.; Rocha, E.R.; Granda, M.A.; Solanki, S.; Hoque, N.J.; Gentry, E.C.; Koo, I.; Reilly, E.R.; et al. Bile salt hydrolase catalyses formation of amine-conjugated bile acids. Nature 2024, 626, 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, C. Targeting gut microbial bile salt hydrolase (BSH) by diet supplements: New insights into dietary modulation of human health. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 7409–7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, J.L.; Cummings, B.P. The 7-α-dehydroxylation pathway: An integral component of gut bacterial bile acid metabolism and potential therapeutic target. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1093420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vico-Oton, E.; Volet, C.; Jacquemin, N.; Dong, Y.; Hapfelmeier, S.; Meibom, K.L.; Bernier-Latmani, R. Strain-dependent induction of primary bile acid 7-dehydroxylation by cholic acid. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, E.S.; Preston, T.; Frost, G.; Morrison, D.J. Role of Gut Microbiota-Generated Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Metabolic and Cardiovascular Health. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2018, 7, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.H. Complex regulatory effects of gut microbial short-chain fatty acids on immune tolerance and autoimmunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.H. Immune regulation by microbiome metabolites. Immunology 2018, 154, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, N.; Faisal, Z.; Irfan, R.; Shah, Y.A.; Batool, S.A.; Zahid, T.; Zulfiqar, A.; Fatima, A.; Jahan, Q.; Tariq, H.; et al. Exploring the serotonin-probiotics-gut health axis: A review of current evidence and potential mechanisms. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, N.J.; Kyloh, M.A.; Travis, L.; Hibberd, T.J. Identification of vagal afferent nerve endings in the mouse colon and their spatial relationship with enterochromaffin cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2024, 396, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, C.B.; Trammell, S.A.J.; Wewer Albrechtsen, N.J.; Schoonjans, K.; Albrechtsen, R.; Gillum, M.P.; Kuhre, R.E.; Holst, J.J. Bile acids drive colonic secretion of glucagon-like-peptide 1 and peptide-YY in rodents. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2019, 316, G574–G584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, M.S.; Daoudi, M.; Prawitt, J.; Ducastel, S.; Touche, V.; Sayin, S.I.; Perino, A.; Brighton, C.A.; Sebti, Y.; Kluza, J.; et al. Farnesoid X receptor inhibits glucagon-like peptide-1 production by enteroendocrine L cells. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Fang, S. Crosstalk between FXR and TGR5 controls glucagon-like peptide 1 secretion to maintain glycemic homeostasis. Lab. Anim. Res. 2018, 34, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, S.; Fu, T.; Choi, S.E.; Li, Y.; Zhu, R.; Kumar, S.; Sun, X.; Yoon, G.; Kang, Y.; Zhong, W.; et al. Transcriptional regulation of autophagy by an FXR-CREB axis. Nature 2014, 516, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carino, A.; Marchianò, S.; Biagioli, M.; Scarpelli, P.; Bordoni, M.; Di Giorgio, C.; Roselli, R.; Fiorucci, C.; Monti, M.C.; Distrutti, E.; et al. The bile acid activated receptors GPBAR1 and FXR exert antagonistic effects on autophagy. Faseb J. 2021, 35, e21271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Wang, Y.; Jin, L.; Huang, W. Bile acids, gut microbiota and metabolic surgery. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 929530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punjabi, M.; Arnold, M.; Rüttimann, E.; Graber, M.; Geary, N.; Pacheco-López, G.; Langhans, W. Circulating glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) inhibits eating in male rats by acting in the hindbrain and without inducing avoidance. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 1690–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, D.I.; de Lartigue, G. Reappraising the role of the vagus nerve in GLP-1-mediated regulation of eating. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.S.; Seeley, R.J.; Sandoval, D.A. Signalling from the periphery to the brain that regulates energy homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanguas-Casás, N.; Barreda-Manso, M.A.; Nieto-Sampedro, M.; Romero-Ramírez, L. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid reduces glial cell activation in an animal model of acute neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanguas-Casás, N.; Barreda-Manso, M.A.; Nieto-Sampedro, M.; Romero-Ramírez, L. TUDCA: An Agonist of the Bile Acid Receptor GPBAR1/TGR5 With Anti-Inflammatory Effects in Microglial Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 232, 2231–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Feng, S.; Zhou, X.; Song, Z.; Li, J.; Li, P. Taxonomic identification of bile salt hydrolase-encoding lactobacilli: Modulation of the enterohepatic bile acid profile. Imeta 2023, 2, e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, L.N.; Mallikarjun, J.; Cattaneo, L.E.; Gangwar, B.; Zhang, Q.; Kerby, R.L.; Stevenson, D.; Rey, F.E.; Amador-Noguez, D. Investigation of Bile Salt Hydrolase Activity in Human Gut Bacteria Reveals Production of Conjugated Secondary Bile Acids. bioRxiv, 2025; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, M.H.; O’Flaherty, S.; Barrangou, R.; Theriot, C.M. Bile salt hydrolases: Gatekeepers of bile acid metabolism and host-microbiome crosstalk in the gastrointestinal tract. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funabashi, M.; Grove, T.L.; Wang, M.; Varma, Y.; McFadden, M.E.; Brown, L.C.; Guo, C.; Higginbottom, S.; Almo, S.C.; Fischbach, M.A. A metabolic pathway for bile acid dehydroxylation by the gut microbiome. Nature 2020, 582, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vital, M.; Rud, T.; Rath, S.; Pieper, D.H.; Schlüter, D. Diversity of Bacteria Exhibiting Bile Acid-inducible 7α-dehydroxylation Genes in the Human Gut. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1016–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.L.; Stine, J.G.; Bisanz, J.E.; Okafor, C.D.; Patterson, A.D. Bile acids and the gut microbiota: Metabolic interactions and impacts on disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, A.S.; Fischbach, M.A. A biosynthetic pathway for a prominent class of microbiota-derived bile acids. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doden, H.L.; Ridlon, J.M. Microbial Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenases: From Alpha to Omega. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridlon, J.M.; Harris, S.C.; Bhowmik, S.; Kang, D.J.; Hylemon, P.B. Consequences of bile salt biotransformations by intestinal bacteria. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Arai, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Fukiya, S.; Wada, M.; Yokota, A. Contribution of the 7β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from Ruminococcus gnavus N53 to ursodeoxycholic acid formation in the human colon. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 3062–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doden, H.; Sallam, L.A.; Devendran, S.; Ly, L.; Doden, G.; Daniel, S.L.; Alves, J.M.P.; Ridlon, J.M. Metabolism of Oxo-Bile Acids and Characterization of Recombinant 12α-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenases from Bile Acid 7α-Dehydroxylating Human Gut Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00235-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doden, H.L.; Wolf, P.G.; Gaskins, H.R.; Anantharaman, K.; Alves, J.M.P.; Ridlon, J.M. Completion of the gut microbial epi-bile acid pathway. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1907271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; An, Y.; Du, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Lu, Y. Effects of short-chain fatty acids on blood glucose and lipid levels in mouse models of diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 199, 107041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, G.; Sleeth, M.L.; Sahuri-Arisoylu, M.; Lizarbe, B.; Cerdan, S.; Brody, L.; Anastasovska, J.; Ghourab, S.; Hankir, M.; Zhang, S.; et al. The short-chain fatty acid acetate reduces appetite via a central homeostatic mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolhurst, G.; Heffron, H.; Lam, Y.S.; Parker, H.E.; Habib, A.M.; Diakogiannaki, E.; Cameron, J.; Grosse, J.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the G-protein-coupled receptor FFAR2. Diabetes 2012, 61, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everard, A.; Lazarevic, V.; Derrien, M.; Girard, M.; Muccioli, G.G.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Possemiers, S.; Van Holle, A.; François, P.; de Vos, W.M.; et al. Responses of gut microbiota and glucose and lipid metabolism to prebiotics in genetic obese and diet-induced leptin-resistant mice. Diabetes 2011, 60, 2775–2786, Erratum in Diabetes 2011, 60, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiedl, O.; Pappa, E.; Konradsson-Geuken, Å.; Ögren, S.O. The role of the serotonin receptor subtypes 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 and its interaction in emotional learning and memory. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shao, D.; Luo, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Cui, R. Role of 5-HT3 receptor on food intake in fed and fasted mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikoff, W.R.; Anfora, A.T.; Liu, J.; Schultz, P.G.; Lesley, S.A.; Peters, E.C.; Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3698–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, K.; Gayle, E.J.; Deb, S. Effect of gut microbiome on serotonin metabolism: A personalized treatment approach. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 2589–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, J.D.; Palanivel, R.; Mottillo, E.P.; Bujak, A.L.; Wang, H.; Ford, R.J.; Collins, A.; Blümer, R.M.; Fullerton, M.D.; Yabut, J.M.; et al. Inhibiting peripheral serotonin synthesis reduces obesity and metabolic dysfunction by promoting brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, M.L.; Egerod, K.L.; Engelstoft, M.S.; Dmytriyeva, O.; Theodorsson, E.; Patel, B.A.; Schwartz, T.W. Enterochromaffin 5-HT cells—A major target for GLP-1 and gut microbial metabolites. Mol. Metab. 2018, 11, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, M.; Modlin, I.M.; Gustafsson, B.I.; Drozdov, I.; Hauso, O.; Pfragner, R. Luminal regulation of normal and neoplastic human EC cell serotonin release is mediated by bile salts, amines, tastants, and olfactants. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 295, G260–G272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellono, N.W.; Bayrer, J.R.; Leitch, D.B.; Castro, J.; Zhang, C.; O’Donnell, T.A.; Brierley, S.M.; Ingraham, H.A.; Julius, D. Enterochromaffin Cells Are Gut Chemosensors that Couple to Sensory Neural Pathways. Cell 2017, 170, 185–198.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundeken, E.; El Aidy, S. Enteroendocrine cells: The gatekeepers of microbiome-gut-brain communication. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Singh, R.; Ghoshal, U.C. Enterochromaffin Cells-Gut Microbiota Crosstalk: Underpinning the Symptoms, Pathogenesis, and Pharmacotherapy in Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2022, 28, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, S.; Yu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, S.; Jia, M.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X. Gut microbiota modulates neurotransmitter and gut-brain signaling. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 287, 127858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.R.; Singh, S.; Hwang, H.S.; Seo, S.O. Using Gut Microbiota Modulation as a Precision Strategy Against Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.M.T. Key Signals Produced by Gut Microbiota Associated with Metabolic Syndrome, Cancer, Cardiovascular Diseases, and Brain Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Luan, J.; He, L.; Pan, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Li, H. Role of the gut-brain axis in neurological diseases: Molecular connections and therapeutic implications (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 56, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, J.S.; Mak, W.Q.; Tan, L.K.S.; Ng, C.X.; Chan, H.H.; Yeow, S.H.; Foo, J.B.; Ong, Y.S.; How, C.W.; Khaw, K.Y. Microbiota–gut–brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei-Baffour, V.O.; Vijaya, A.K.; Burokas, A.; Daliri, E.B. Psychobiotics and the gut-brain axis: Advances in metabolite quantification and their implications for mental health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 7085–7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrut, S.M.; Bragaru, A.M.; Munteanu, A.E.; Moldovan, A.D.; Moldovan, C.A.; Rusu, E. Gut over Mind: Exploring the Powerful Gut-Brain Axis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, Y.N.; Alqifari, S.F.; Alshehri, K.; Alhowiti, A.; Mirghani, H.; Alrasheed, T.; Aljohani, F.; Alghamdi, A.; Hetta, H.F. Microbiome Gut-Brain-Axis: Impact on Brain Development and Mental Health. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 10813–10833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, E.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, C.; Long, G.; Chen, B.; Guo, R.; Fang, M.; Jiang, M. Potential Roles of Enterochromaffin Cells in Early Life Stress-Induced Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 837166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T.; Lechner, F.; Krieger, J.P.; García-Cáceres, C. Neuroendocrine gut-brain signaling in obesity. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 36, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welathanthree, M.; Keating, D.J.; Macefield, V.G.; Carnevale, D.; Marques, F.Z.; Muralitharan, R.R. Cross-talk between microbiota-gut-brain axis and blood pressure regulation. Clin. Sci. 2025, 139, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, R.; Qaisar, R.; Maciver, S.; Khan, N.A. Gut microbiome, stress and interventional strategies using hardy animals. Future Sci. OA 2025, 11, 2583020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, G.; Rossi, S.; Sfratta, G.; Traversi, G.; Lisci, F.M.; Anesini, M.B.; Pola, R.; Gasbarrini, A.; Gaetani, E.; Mazza, M. Gut Microbiota: A New Challenge in Mood Disorder Research. Life 2025, 15, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, H.; Arbab, S.; Tian, Y.; Liu, C.Q.; Chen, Y.; Qijie, L.; Khan, M.I.U.; Hassan, I.U.; Li, K. The gut microbiota-brain axis in neurological disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1225875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.T.; Zohair, M.; Khan, A.; Kashif, A.; Mumtaz, S.; Muskan, F. From Gut to Brain: The roles of intestinal microbiota, immune system, and hormones in intestinal physiology and gut-brain-axis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2025, 607, 112599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Yu, B.; Chen, D. The effects of gut microbiota on appetite regulation and the underlying mechanisms. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2414796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carías Domínguez, A.M.; de Jesús Rosa Salazar, D.; Stefanolo, J.P.; Cruz Serrano, M.C.; Casas, I.C.; Zuluaga Peña, J.R. Intestinal Dysbiosis: Exploring Definition, Associated Symptoms, and Perspectives for a Comprehensive Understanding—A Scoping Review. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, M.; Fan, Y.; Ma, Q.; Yang, D.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Zhao, B.; Zhan, X.; Qi, Z.; Ren, Y.; et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis promotes cognitive impairment via bile acid metabolism in major depressive disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, H.A.; Savidge, T.C. Gut microbiome metagenomics in clinical practice: Bridging the gap between research and precision medicine. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2569739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Tian, T.; Xie, J.; Wang, X.; Deng, W.; Hao, N.; Li, C. Relationship between gut microbiota dysbiosis and bile acid in patients with hepatitis B-induced cirrhosis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahitham, W.; Banoun, Y.; Aljahdali, M.; Almuaiqly, G.; Bahshwan, S.M.; Aljahdali, L.; Sanai, F.M.; Rosado, A.S.; Sergi, C.M. “Trust your gut”: Exploring the connection between gut microbiome dysbiosis and the advancement of Metabolic Associated Steatosis Liver Disease (MASLD)/Metabolic Associated Steatohepatitis (MASH): A systematic review of animal and human studies. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1637071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaple-Gil, A.M.; Santiesteban-Velázquez, M.; Urbizo Vélez, J.J. Association Between Oral Microbiota Dysbiosis and the Risk of Dementia: A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadifard, E.; Hokmabadi, M.; Hashemi, M.; Bereimipour, A. Linking gut microbiota dysbiosis to molecular pathways in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2024, 1845, 149242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, P.; Yadav, R.; Vishwakarma, R.K.; Shekhar, S.; Pathak, A.; Singh, C. An Integrative Analysis of Metagenomic and Metabolomic Profiling Reveals Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis and Metabolic Alterations in ALS: Potential Biomarkers and Therapeutic Insights. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2025, 16, 2691–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]