The Functional Role of Gate Loop Residues in Arrestin Binding to GPCRs

Abstract

1. Introduction

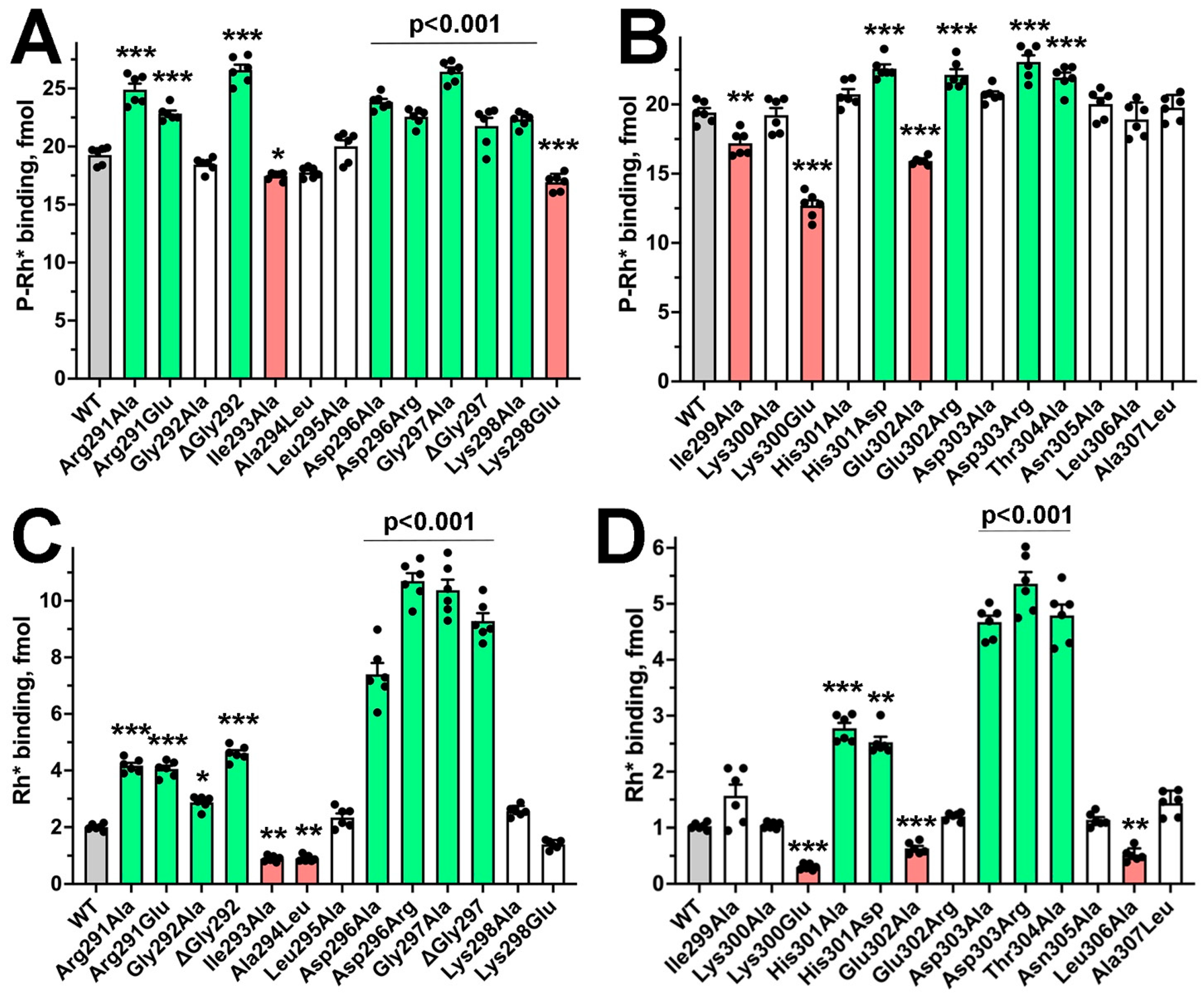

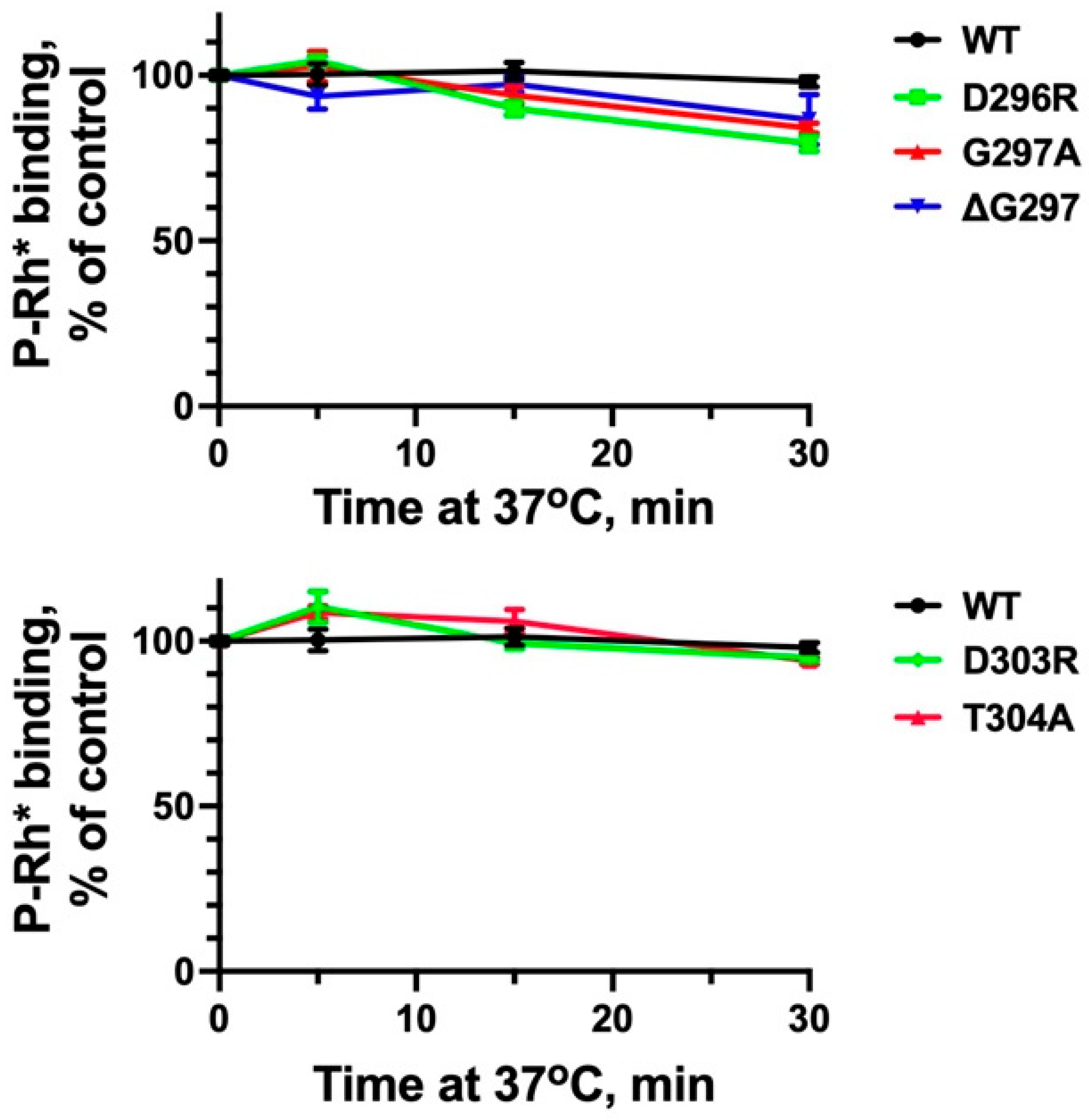

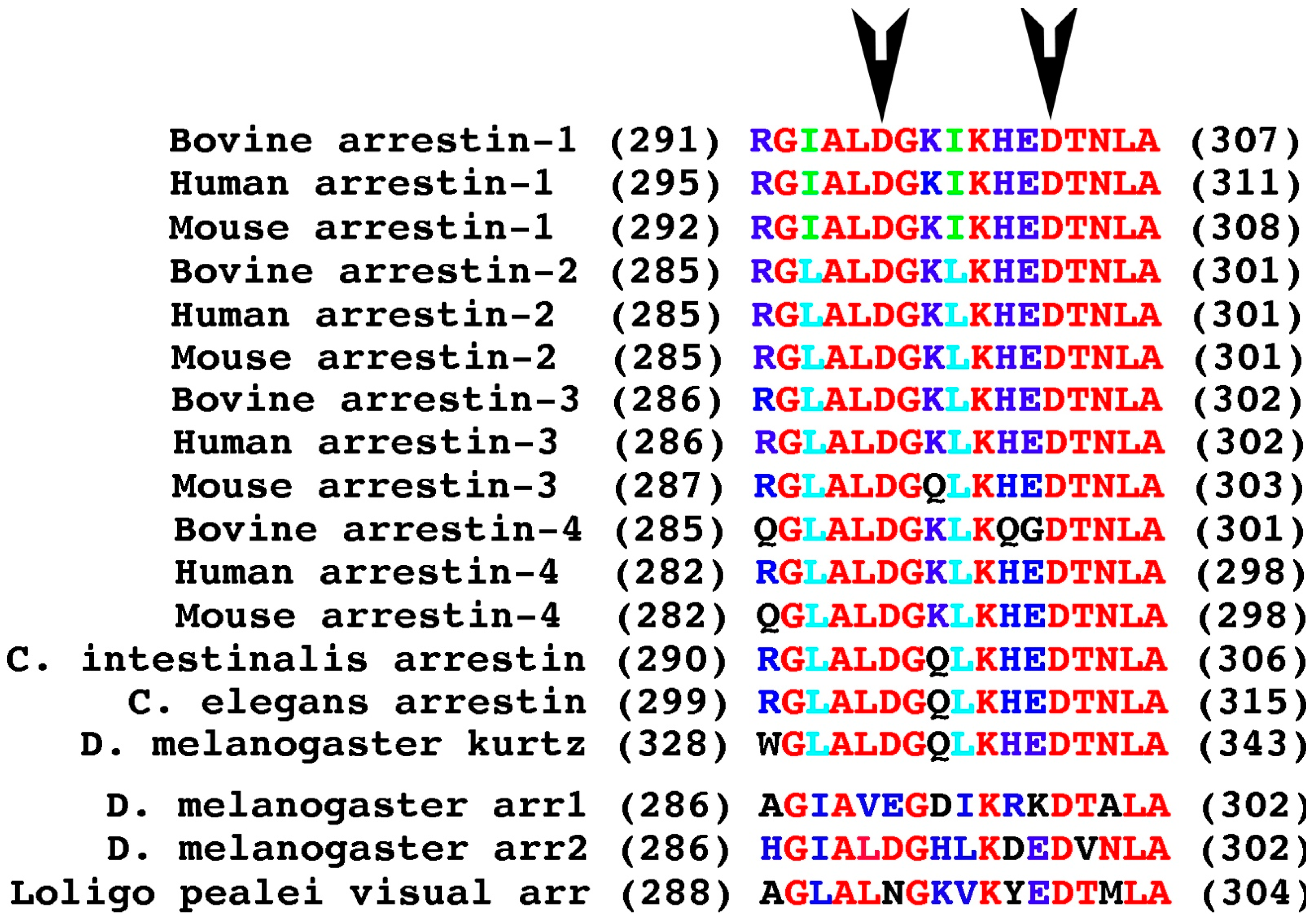

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fredriksson, R.; Lagerstrom, M.C.; Lundin, L.G.; Schioth, H.B. The G-protein-coupled receptors in the human genome form five main families. Phylogenetic analysis, paralogon groups, and fingerprints. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 63, 1256–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Indrischek, H.; Prohaska, S.J.; Gurevich, V.V.; Gurevich, E.V.; Stadler, P.F. Uncovering missing pieces: Duplication and deletion history of arrestins in deuterostomes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, K.P.; Scheerer, P.; Hildebrand, P.W.; Choe, H.W.; Park, J.H.; Heck, M.; Ernst, O.P. A G protein-coupled receptor at work: The rhodopsin model. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009, 34, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carman, C.V.; Benovic, J.L. G-protein-coupled receptors: Turn-ons and turn-offs. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1998, 8, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, H. Light-regulated binding of rhodopsin kinase and other proteins to cattle photoreceptor membranes. Biochemistry 1978, 17, 4389–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, T.; Dietzschold, B.; Craft, C.M.; Wistow, G.; Early, J.J.; Donoso, L.A.; Horwitz, J.; Tao, R. Primary and secondary structure of bovine retinal S antigen (48 kDa protein). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 6975–6979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Seo, J.; Chen, J.; Gurevich, E.V.; Gurevich, V.V. Arrestin-1 expression in rods: Balancing functional performance and photoreceptor health. Neuroscience 2011, 174, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.M.; Gurevich, E.V.; Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Ahmed, M.R.; Song, X.; Gurevich, V.V. Each rhodopsin molecule binds its own arrestin. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 3125–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikonov, S.S.; Brown, B.M.; Davis, J.A.; Zuniga, F.I.; Bragin, A.; Pugh, E.N., Jr.; Craft, C.M. Mouse cones require an arrestin for normal inactivation of phototransduction. Neuron 2008, 59, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, V.V. Arrestins: A Small Family of Multi-Functional Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.A.; Schubert, C.; Gurevich, V.V.; Sigler, P.B. The 2.8 A crystal structure of visual arrestin: A model for arrestin’s regulation. Cell 1999, 97, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Gurevich, V.V.; Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Sigler, P.B.; Schubert, C. Crystal structure of beta-arrestin at 1.9 A: Possible mechanism of receptor binding and membrane translocation. Structure 2001, 9, 869–880. [Google Scholar]

- Milano, S.K.; Pace, H.C.; Kim, Y.M.; Brenner, C.; Benovic, J.L. Scaffolding functions of arrestin-2 revealed by crystal structure and mutagenesis. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 3321–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.B.; Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Robert, J.; Hanson, S.M.; Raman, D.; Knox, B.E.; Kono, M.; Navarro, J.; Gurevich, V.V. Crystal Structure of Cone Arrestin at 2.3Å: Evolution of Receptor Specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 354, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Gimenez, L.E.; Gurevich, V.V.; Spiller, B.W. Crystal structure of arrestin-3 reveals the basis of the difference in receptor binding between two non-visual arrestins. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 406, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Zhou, X.E.; Gao, X.; He, Y.; Liu, W.; Ishchenko, A.; Barty, A.; White, T.A.; Yefanov, O.; Han, G.W.; et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin bound to arrestin determined by femtosecond X-ray laser. Nature 2015, 523, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.E.; He, Y.; de Waal, P.W.; Gao, X.; Kang, Y.; Van Eps, N.; Yin, Y.; Pal, K.; Goswami, D.; White, T.A.; et al. Identification of Phosphorylation Codes for Arrestin Recruitment by G protein-Coupled Receptors. Cell 2017, 170, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Li, Z.; Jin, M.; Yin, Y.L.; de Waal, P.W.; Pal, K.; Yin, Y.; Gao, X.; He, Y.; Gao, J.; et al. A complex structure of arrestin-2 bound to a G protein-coupled receptor. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staus, D.P.; Hu, H.; Robertson, M.J.; Kleinhenz, A.L.W.; Wingler, L.M.; Capel, W.D.; Latorraca, N.R.; Lefkowitz, R.J.; Skiniotis, G. Structure of the M2 muscarinic receptor-β-arrestin complex in a lipid nanodisc. Nature 2020, 579, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Warne, T.; Nehmé, R.; Pandey, S.; Dwivedi-Agnihotri, H.; Chaturvedi, M.; Edwards, P.C.; García-Nafría, J.; Leslie, A.G.W.; Shukla, A.K.; et al. Molecular basis of β-arrestin coupling to formoterol-bound β(1)-adrenoceptor. Nature 2020, 583, 862–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.; Shen, Q.; Cai, C.; Ding, Y.; Shen, D.D.; Guo, J.; Qin, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Snapshot of the cannabinoid receptor 1-arrestin complex unravels the biased signaling mechanism. Cell 2023, 186, 5784–5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Masureel, M.; Qianhui, Q.; Janetzko, J.; Inoue, A.; Kato, H.E.; Robertson, M.J.; Nguyen, K.C.; Glenn, J.S.; Skiniotis, G.; et al. Structure of the neurotensin receptor 1 in complex with β-arrestin 1. Nature 2020, 579, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bous, J.; Fouillen, A.; Orcel, H.; Trapani, S.; Cong, X.; Fontanel, S.; Saint-Paul, J.; Lai-Kee-Him, J.; Urbach, S.; Sibille, N.; et al. Structure of the vasopressin hormone-V2 receptor-β-arrestin1 ternary complex. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo7761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Barros-Álvarez, X.; Zhang, S.; Kim, K.; Dämgen, M.A.; Panova, O.; Suomivuori, C.M.; Fay, J.F.; Zhong, X.; Krumm, B.E.; et al. Signaling snapshots of a serotonin receptor activated by the prototypical psychedelic LSD. Neuron 2022, 110, 3154–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Lin, X.; Zhao, L.; He, M.; Yu, J.; Zhang, B.; Ma, Y.; Chang, X.; Tang, Y.; Luo, T.; et al. Noncanonical Agonist-Dependent and -Independent Arrestin Recruitment of GPR1. Science 2025, 390, eadt8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Schafer, C.T.; Mukherjee, S.; Wang, K.; Gustavsson, M.; Fuller, J.R.; Tepper, K.; Lamme, T.D.; Aydin, Y.; Agrawal, P.; et al. Effect of phosphorylation barcodes on arrestin binding to a chemokine receptor. Nature 2025, 643, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.K.; Manglik, A.; Kruse, A.C.; Xiao, K.; Reis, R.I.; Tseng, W.C.; Staus, D.P.; Hilger, D.; Uysal, S.; Huang, L.Y.; et al. Structure of Active Beta-Arrestin-1 bound to a G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Phosphopeptide. Nature 2013, 497, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sente, A.; Peer, R.; Srivastava, A.; Baidya, M.; Lesk, A.M.; Balaji, S.; Shukla, A.K.; Babu, M.M.; Flock, T. Molecular mechanism of modulating arrestin conformation by GPCR phosphorylation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018, 25, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sander, C.L.; Luu, J.; Kim, K.; Furkert, D.; Jang, K.; Reichenwallner, J.; Kang, M.; Lee, H.J.; Eger, B.T.; Choe, H.W.; et al. Structural evidence for visual arrestin priming via complexation of phosphoinositols. Structure 2022, 30, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Van Eps, N.; Eger, B.T.; Rauscher, S.; Yedidi, R.S.; Moroni, T.; West, G.M.; Robinson, K.A.; Griffin, P.R.; Mitchell, J.; et al. A Novel Polar Core and Weakly Fixed C-Tail in Squid Arrestin Provide New Insight into Interaction with Rhodopsin. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 4102–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granzin, J.; Wilden, U.; Choe, H.W.; Labahn, J.; Krafft, B.; Buldt, G. X-ray crystal structure of arrestin from bovine rod outer segments. Nature 1998, 391, 918–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Paz, C.L.; Schubert, C.; Hirsch, J.A.; Sigler, P.B.; Gurevich, V.V. How does arrestin respond to the phosphorylated state of rhodopsin? J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 11451–11454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Huh, E.K.; Gurevich, E.V.; Gurevich, V.V. The finger loop as an activation sensor in arrestin. J. Neurochem. 2021, 157, 1138–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Zheng, C.; May, M.B.; Karnam, P.C.; Gurevich, E.V.; Gurevich, V.V. Lysine in the lariat loop of arrestins does not serve as phosphate sensor. J. Neurochem. 2021, 156, 435–444. [Google Scholar]

- Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Schubert, C.; Climaco, G.C.; Gurevich, Y.V.; Velez, M.-G.; Gurevich, V.V. An additional phosphate-binding element in arrestin molecule: Implications for the mechanism of arrestin activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 41049–41057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurevich, V.V. The selectivity of visual arrestin for light-activated phosphorhodopsin is controlled by multiple nonredundant mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 15501–15506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Francis, D.J.; Van Eps, N.; Kim, M.; Hanson, S.M.; Klug, C.S.; Hubbell, W.L.; Gurevich, V.V. The role of arrestin alpha-helix I in receptor binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 395, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Hanson, S.M.; Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Song, X.; Cleghorn, W.M.; Hubbell, W.L.; Gurevich, V.V. Robust self-association is a common feature of mammalian visual arrestin-1. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 2235–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.M.; Van Eps, N.; Francis, D.J.; Altenbach, C.; Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Arshavsky, V.Y.; Klug, C.S.; Hubbell, W.L.; Gurevich, V.V. Structure and function of the visual arrestin oligomer. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 1726–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Gross, O.P.; Emelianoff, K.; Mendez, A.; Chen, J.; Gurevich, E.V.; Burns, M.E.; Gurevich, V.V. Enhanced arrestin facilitates recovery and protects rods lacking rhodopsin phosphorylation. Curr. Biol. CB 2009, 19, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.C. A splice variant of arrestin from human retina. Exp. Eye Res. 1996, 62, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, M.; Syed, M.; Bugra, K.; Whelan, J.P.; McGinnis, J.F.; Shinohara, T. Structural analysis of mouse S-antigen. Gene 1988, 73, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne-Marr, R.; Gurevich, V.V.; Goldsmith, P.; Bodine, R.C.; Sanders, C.; Donoso, L.A.; Benovic, J.L. Polypeptide variants of beta-arrestin and arrestin3. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 15640–15648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parruti, G.; Peracchia, F.; Sallese, M.; Ambrosini, G.; Masini, M.; Rotilio, D.; De Blasi, A. Molecular analysis of human beta-arrestin-1: Cloning, tissue distribution, and regulation of expression. Identification of two isoforms generated by alternative splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 9753–9761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsmore, S.F.; Peppel, K.; Suh, D.; Caron, M.G.; Lefkowitz, R.J.; Seldin, M.F. Genetic mapping of the beta-arrestin 1 and 2 genes on mouse chromosomes 7 and 11 respectively. Mamm. Genome 1995, 6, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapoport, B.; Kaufman, K.D.; Chazenbalk, G.D. Cloning of a member of the arrestin family from a human thyroid cDNA library. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1992, 84, R39–R43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, T.; Ohguro, H.; Sohma, H.; Kuroki, Y.; Wada, H.; Okisaka, S.; Murakami, A. Purification and characterization of bovine cone arrestin (cArr). FEBS Lett. 2000, 470, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, A.; Yajima, T.; Sakuma, H.; McLaren, M.J.; Inana, G. X-arrestin: A new retinal arrestin mapping to the X chromosome. FEBS Lett. 1993, 334, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, D.R.; Mecklenburg, K.L.; Pollock, J.A.; Vihtelic, T.S.; Benzer, S. Twenty Drosophila visual system cDNA clones: One is a homolog of human arrestin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 1008–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Komori, N.; Kobayashi, H.; Sakai, Y.; Hotta, Y.; Matsumoto, H. A 49-kilodalton phosphoprotein in the Drosophila photoreceptor is an arrestin homolog. Science 1990, 246, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayeenuddin, L.H.; Mitchell, J. Squid visual arrestin: cDNA cloning and calcium-dependent phosphorylation by rhodopsin kinase (SQRK). J. Neurochem. 2003, 85, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.C.; Tift, F.W.; McCauley, A.; Liu, L.; Roman, G. Functional characterization of kurtz, a Drosophila non-visual arrestin, reveals conservation of GPCR desensitization mechanisms. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 38, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmitessa, A.; Hess, H.A.; Bany, I.A.; Kim, Y.M.; Koelle, M.R.; Benovic, J.L. Caenorhabditus elegans arrestin regulates neural G protein signaling and olfactory adaptation and recovery. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 24649–24662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, M.; Orii, H.; Yoshida, N.; Jojima, E.; Horie, T.; Yoshida, R.; Haga, T.; Tsuda, M. Ascidian arrestin (Ci-arr), the origin of the visual and nonvisual arrestins of vertebrate. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 5112–5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, C.; Lin, S.; Yan, X.; Cai, H.; Yi, C.; Ma, L.; Chu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Tail engagement of arrestin at the glucagon receptor. Nature 2023, 620, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Li, X.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Shi, P.; Zhang, H.; Wang, T.; Sun, W.; Ling, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. Molecular mechanism of the arrestin-biased agonism of neurotensin receptor 1 by an intracellular allosteric modulator. Cell Res. 2025, 35, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Perry, N.A.; Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Berndt, S.; Gilbert, N.C.; Zhuo, Y.; Singh, P.K.; Tholen, J.; Ohi, M.D.; Gurevich, E.V.; et al. Structural basis of arrestin-3 activation and signaling. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, V.V.; Pals-Rylaarsdam, R.; Benovic, J.L.; Hosey, M.M.; Onorato, J.J. Agonist-receptor-arrestin, an alternative ternary complex with high agonist affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 28849–28852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celver, J.; Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Chavkin, C.; Gurevich, V.V. Conservation of the phosphate-sensitive elements in the arrestin family of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 9043–9048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovoor, A.; Celver, J.; Abdryashitov, R.I.; Chavkin, C.; Gurevich, V.V. Targeted construction of phosphorylation-independent b-arrestin mutants with constitutive activity in cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 6831–6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermaier, M.K.; Peterhans, C.; Jaussi, R.; Deupi, X.; Standfuss, J. Functional map of arrestin-1 at single amino acid resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 1825–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterhans, C.; Lally, C.C.; Ostermaier, M.K.; Sommer, M.E.; Standfuss, J. Functional map of arrestin binding to phosphorylated opsin, with and without agonist. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Ashim, J.; Ham, D.; Yu, W.; Chung, K.Y. Roles of the gate loop in beta-arrestin-1 conformational dynamics and phosphorylated receptor interaction. Structure 2024, 32, 1358–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

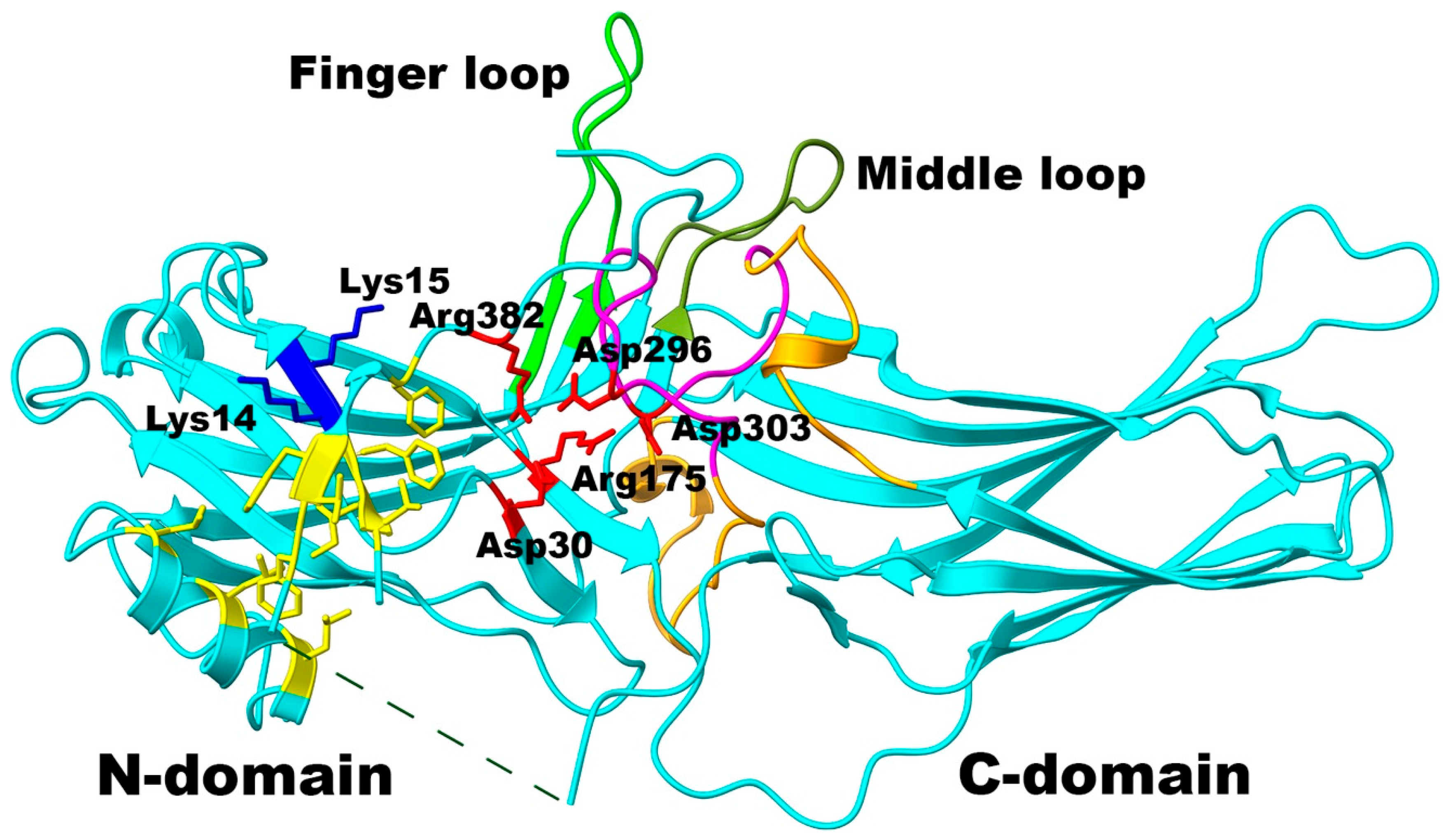

- Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Huh, E.K.; Karnam, P.C.; Oviedo, S.; Gurevich, E.V.; Gurevich, V.V. The Role of Arrestin-1 Middle Loop in Rhodopsin Binding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Weinstein, L.D.; Zheng, C.; Gurevich, E.V.; Gurevich, V.V. Functional Role of Arrestin-1 Residues Interacting with Unphosphorylated Rhodopsin Elements. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, E.V.; Gurevich, V.V. Arrestins are ubiquitous regulators of cellular signaling pathways. Genome Biol. 2006, 7, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Chen, Q.; Palazzo, M.C.; Brooks, E.K.; Altenbach, C.; Iverson, T.M.; Hubbell, W.L.; Gurevich, V.V. Engineering visual arrestin-1 with special functional characteristics. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 11741–11750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloway, P.G.; Dolph, P.J. A role for the light-dependent phosphorylation of visual arrestin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 6072–6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentrop, J.; Paulsen, R. Light-modulated ADP-ribosylation, protein phosphorylation and protein binding in isolated fly photoreceptor membranes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1986, 161, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, A.K.; Xia, H.; Yan, L.; Liu, C.H.; Hardie, R.C.; Ready, D.F. Arrestin translocation is stoichiometric to rhodopsin isomerization and accelerated by phototransduction in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron 2010, 67, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, V.V. Use of bacteriophage RNA polymerase in RNA synthesis. Methods Enzymol. 1996, 275, 382–397. [Google Scholar]

- Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Lee, R.J.; Zhou, X.E.; Franz, A.; Xu, Q.; Xu, H.E.; Gurevich, V.V. Functional role of the three conserved cysteines in the N domain of visual arrestin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 12496–12502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Hosey, M.M.; Benovic, J.L.; Gurevich, V.V. Mapping the arrestin-receptor interface: Structural elements responsible for receptor specificity of arrestin proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 1262–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurevich, V.V.; Benovic, J.L. Cell-free expression of visual arrestin. Truncation mutagenesis identifies multiple domains involved in rhodopsin interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 21919–21923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, J.H. Preparing Rod Outer Segment Membranes, Regenerating Rhodopsin, and Determining Rhodopsin Concentration. Methods Neurosci. 1993, 15, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, J.H.; Nawrocki, J.P.; Hargrave, P.A. Phosphorylation sites in bovine rhodopsin. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 4968–4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Raman, D.; Wei, J.; Kennedy, M.J.; Hurley, J.B.; Gurevich, V.V. Regulation of arrestin binding by rhodopsin phosphorylation level. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 32075–32083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, A.; Burns, M.E.; Roca, A.; Lem, J.; Wu, L.W.; Simon, M.I.; Baylor, D.A.; Chen, J. Rapid and reproducible deactivation of rhodopsin requires multiple phosphorylation sites. Neuron 2000, 28, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilden, U.; Kühn, H. Light-dependent phosphorylation of rhodopsin: Number of phosphorylation sites. Biochemistry 1982, 21, 3014–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovchinnikov, I.A.; Abdulaev, N.G.; Feĭgina, M.I.; Artamonov, I.D.; Bogachuk, A.S. Visual rhodopsin. III. Complete Amino Acid Sequence and Topography in a Membrane. Bioorg. Khim. 1983, 9, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hargrave, P.A.; Fong, S.L. The Amino- and Carboxyl-Terminal Sequence of Bovine Rhodopsin. J. Supramol. Struct. 1977, 6, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Ghazi, D.; Gurevich, E.V.; Gurevich, V.V. The Functional Role of Gate Loop Residues in Arrestin Binding to GPCRs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412154

Vishnivetskiy SA, Ghazi D, Gurevich EV, Gurevich VV. The Functional Role of Gate Loop Residues in Arrestin Binding to GPCRs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412154

Chicago/Turabian StyleVishnivetskiy, Sergey A., Daria Ghazi, Eugenia V. Gurevich, and Vsevolod V. Gurevich. 2025. "The Functional Role of Gate Loop Residues in Arrestin Binding to GPCRs" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412154

APA StyleVishnivetskiy, S. A., Ghazi, D., Gurevich, E. V., & Gurevich, V. V. (2025). The Functional Role of Gate Loop Residues in Arrestin Binding to GPCRs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412154