Mass Spectrometry Imaging Elucidates the Precise Localization and Site-Specific Functions of Skin Lipids

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

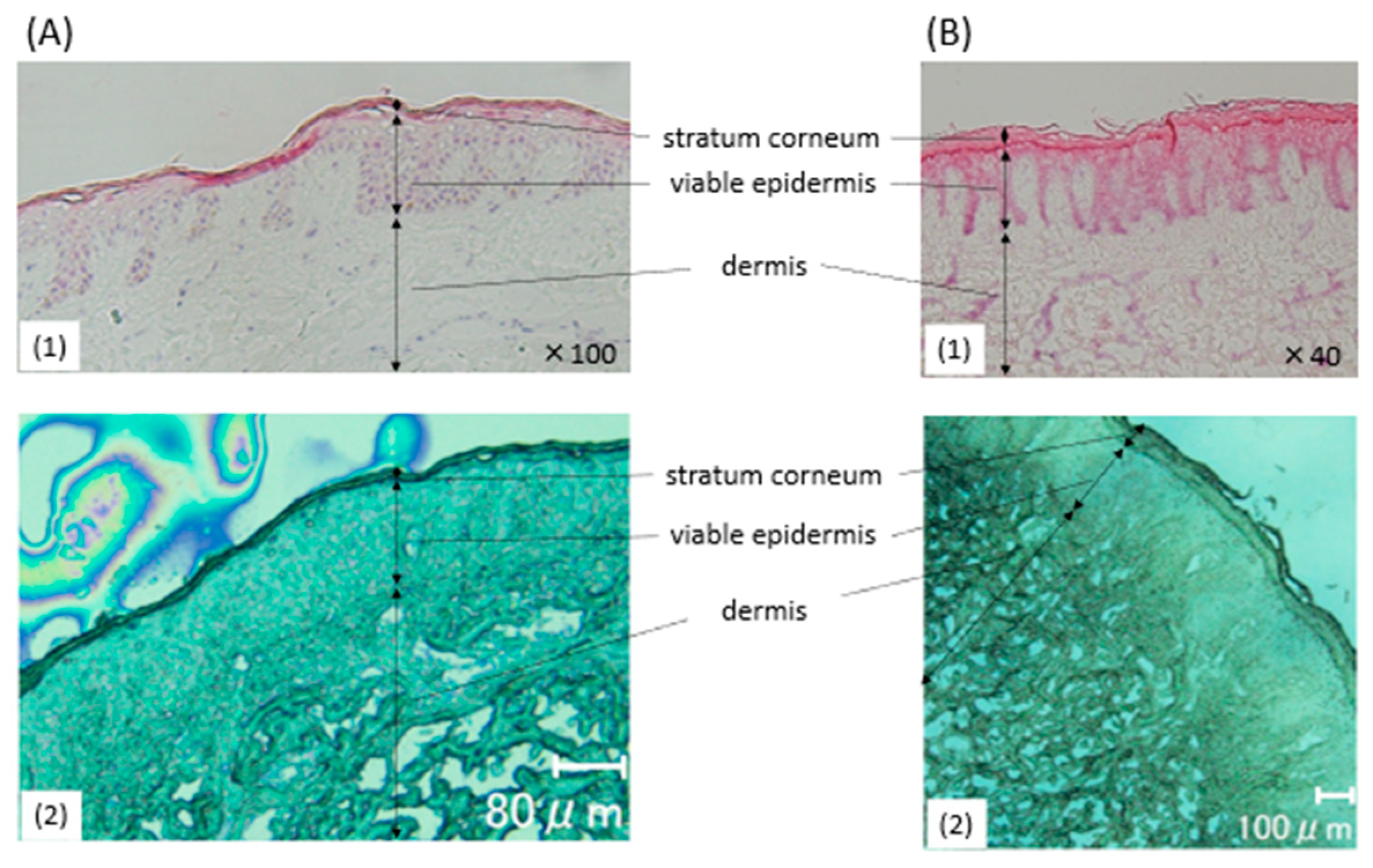

2.1. Histological Findings of the Healthy Specimens

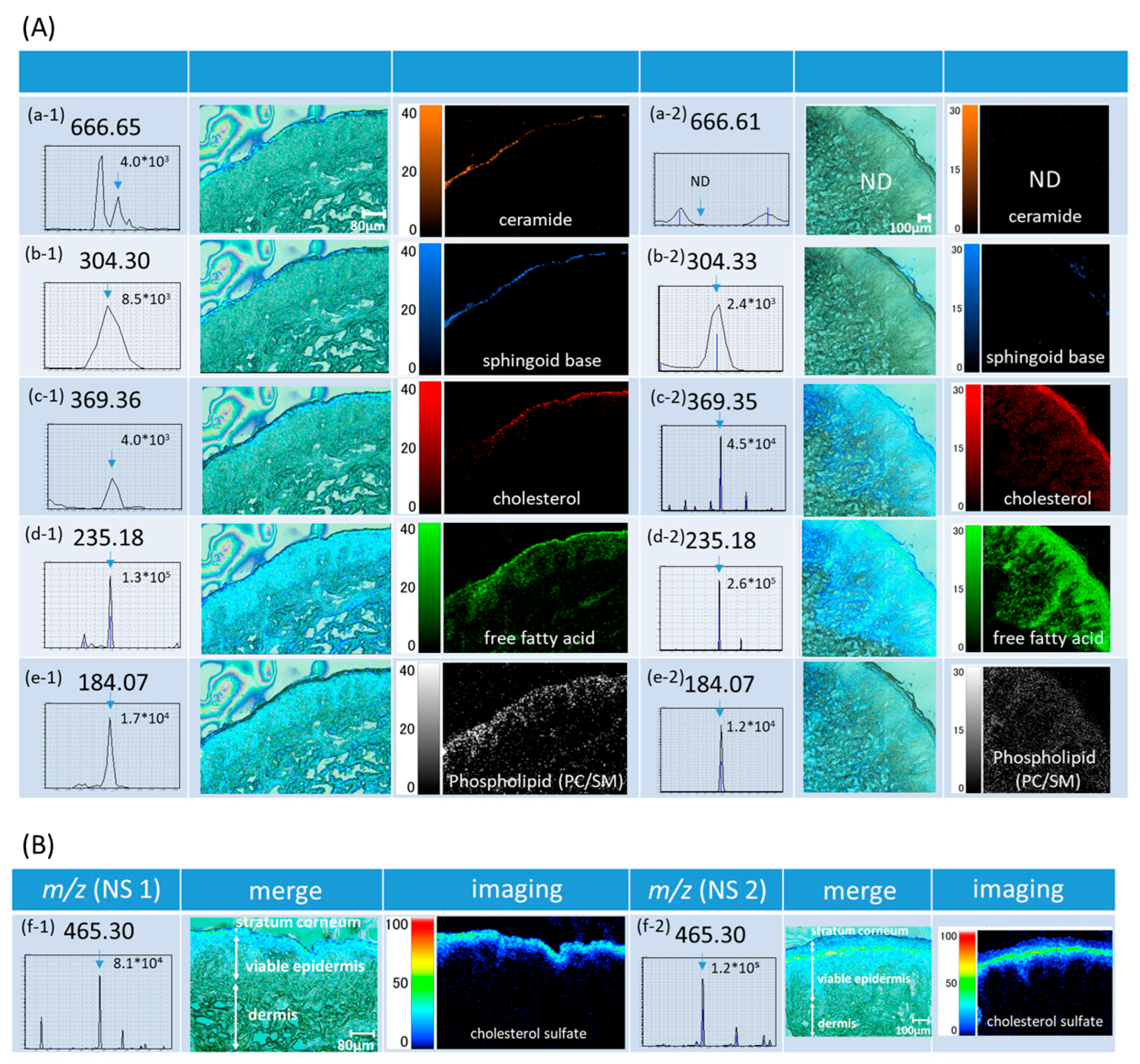

2.2. MSI of Skin Lipids

2.2.1. Lipids in the Stratum Corneum—Intercellular Lipids-

2.2.2. Cholesterol Sulfate

2.2.3. Lipids in the Viable Epidermis

2.3. MS/MS for Identification of Cer and Chol

2.4. Localization Analysis of Intercellular Lipids

2.4.1. Ceramide Is Localized in the Outermost Layer Among Intercellular Lipids

2.4.2. Sphingoid Base Is Lost Through Desquamation

2.5. ROI Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations

6. Materials and Methods

6.1. Skin Samples

6.2. Materials

6.3. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MALDI-MSI)

6.4. Identification of Lipids

6.5. Localization Analyses of Skin Lipids

6.6. Region of Interest (ROI) Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cer | ceramide |

| SB | sphingoid base |

| Chol | cholesterol |

| FFA | free fatty acid |

| PC | phosphatidylcholine |

| PL | phospholipid |

| SM | sphingomyelin |

| CS | cholesterol sulfate |

| MSI | mass spectrometry imaging |

| NS | normal skin |

| SC | stratum corneum |

References

- Feingold, K.R.; Elias, P.M. Role of Lipids in the Formation and Maintenance of the Cutaneous Permeability Barrier. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2013, 1841, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knox, S.; O’boyle, N.M. Skin Lipids in Health and Disease: A Review. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2021, 236, 105055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleva, E.; Berdyshev, E.; Leung, D.Y.M. Epithelial Barrier Repair and Prevention of Allergy. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 1463–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, P.M.; Wakefield, J. Lipid Abnormalities and Lipid-Based Repair Strategies in Atopic Dermatitis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2015, 1841, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, S.; Setty, S.R.G. Epidermal Lamellar Body Biogenesis: Insight into the Roles of Golgi and Lysosomes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 701950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egawa, G.; Kabashima, K. Barrier Dysfunction in the Skin Allergy. Allergol. Int. 2017, 67, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Ohno, Y.; Kihara, A. Whole Picture of Human Stratum Corneum Ceramides, Including the Chain-Length Diversity of Long-Chain Bases. J. Lipid Res. 2022, 63, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, I.; Han, H.; Hollander, L.D.; Svensson, S.; Öfverstedt, L.; Anwar, J.; Brewer, J.; Bloksgaard, M.; Laloeuf, A.; Nosek, D.; et al. The Human Skin Barrier is Organized as Stacked Bilayers of Fully Extended Ceramides with Cholesterol Molecules Associated with the Ceramide Sphingoid Moiety. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 2215–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, P.M.; Caprioli, R.M. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Imaging Mass Spectrometry: In Situ Molecular Mapping. Biochemistry 2014, 52, 3818–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokoro, S.; Ogawa, T.; Hayashi, S.; Igawa, K. High-resolution Mass Spectrometry Imaging Reveals Skin Lipid Changes and the Cholesterol Sulphate Cycle during Keratinization. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, e456–e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, E.H.; Williams, M.L.; Elias, P.M. The epidermal cholesterol sulfate cycle. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1984, 10, 866–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Agthoven, M.A.; Barrow, M.P.; Chiron, L.; Coutouly, M.; Kilgour, D.; Wootton, C.A.; Wei, J.; Soulby, A.; Delsuc, M.; Rolando, C.; et al. Differentiating Fragmentation Pathways of Cholesterol by Two-Dimensional Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2015, 26, 2105–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, P.M. The how, Why and Clinical Importance of Stratum Corneum Acidification. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 26, 999–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Yosipovitch, G. Skin pH: From Basic SciencE to Basic Skin Care. Acta Derm. Venerol. 2013, 93, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippke, F.; Schreiner, V.; Schwanitz, H. The Acidic Milieu of the Horny Layer. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2002, 3, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K.; Ito, Y.; Furuichi, Y.; Matsui, T.; Horikawa, H.; Miyano, T.; Okada, T.; Van Logtestijn, M.; Tanaka, R.J.; Miyawaki, A.; et al. Three Stepwise pH Progressions in Stratum Corneum for Homeostatic Maintenance of the Skin. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamp, M.A.; Williams, M.L.; Elias, P.M. Human epidermal lipids: Characterization and modulations during differentiation. J. Lipid Res. 1983, 24, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, P.M.; Williams, M.L.; Choi, E.; Feingold, K.R. Role of Cholesterol Sulfate in Epidermal Structure and Function: Lessons from X-Linked Ichthyosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2015, 1841, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D.R.; Brodbelt, J.S. Structural Characterization of Phosphatidylcholines using 193 Nm Ultraviolet Photodissociation Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 1516–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Kadono-Maekubo, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Furuichi, Y.; Shiraga, K.; Sasaki, H.; Ishida, A.; Takahashi, S.; Okada, T.; Toyooka, K.; et al. A Unique Mode of Keratinocyte Death Requires Intracellular Acidification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020722118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibardi, L.; Conway, S.J.; Matsui, T. Epidermal Barrier Development Via Corneoptosis: A Unique Form of Cell Death in Stratum Granulosum Cells. J. Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NS1 | ROI A: Stratum Corneum | ROI B: Viable Epidermis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m/z | p-value | mean | standard deviation | median | mean | standard deviation | median |

| 184.07 | 5.8 × 10−19 | 21.6 | 46.7 | 0 | 54.9 | 80.2 | 0 |

| 235.18 | 3.0 × 10−73 | 640.6 | 472.6 | 540.0 | 267.5 | 214.0 | 229.5 |

| 304.30 | 0 | 178.5 | 267.2 | 0 | 0.2 | 3.7 | 0 |

| 369.35 | 7.8 × 10−161 | 77.0 | 95.1 | 75.0 | 6.8 | 26.1 | 0 |

| 666.64 | 3.2 × 10−173 | 72.0 | 125.5 | 0 | 1.5 | 11.6 | 0 |

| NS2 | ROI A: Stratum corneum | ROI B: Viable epidermis | |||||

| m/z | p-value | mean | standard deviation | median | mean | standard deviation | median |

| 184.09 | 4.5 × 10−66 | 10.2 | 28.5 | 0 | 24.3 | 44.0 | 0 |

| 235.17 | 3.2 × 10−9 | 637.7 | 357.6 | 592.0 | 590.5 | 320.8 | 542.0 |

| 304.30 | 7.6 × 10−21 | 18.7 | 76.8 | 0 | 0.2 | 3.4 | 0 |

| 369.34 | 0 | 203.7 | 147.6 | 180.0 | 95.6 | 80.9 | 78.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tokoro, S.; Ogawa, T.; Hayashi, S.; Igawa, K. Mass Spectrometry Imaging Elucidates the Precise Localization and Site-Specific Functions of Skin Lipids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412114

Tokoro S, Ogawa T, Hayashi S, Igawa K. Mass Spectrometry Imaging Elucidates the Precise Localization and Site-Specific Functions of Skin Lipids. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412114

Chicago/Turabian StyleTokoro, Shown, Tadayuki Ogawa, Shujiro Hayashi, and Ken Igawa. 2025. "Mass Spectrometry Imaging Elucidates the Precise Localization and Site-Specific Functions of Skin Lipids" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412114

APA StyleTokoro, S., Ogawa, T., Hayashi, S., & Igawa, K. (2025). Mass Spectrometry Imaging Elucidates the Precise Localization and Site-Specific Functions of Skin Lipids. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412114