Short- and Long-Term Effects of Sodium Phenylbutyrate on White Matter and Sensorimotor and Cognitive Behavior in a Mild Murine Model of Encephalopathy of Prematurity

Abstract

1. Introduction

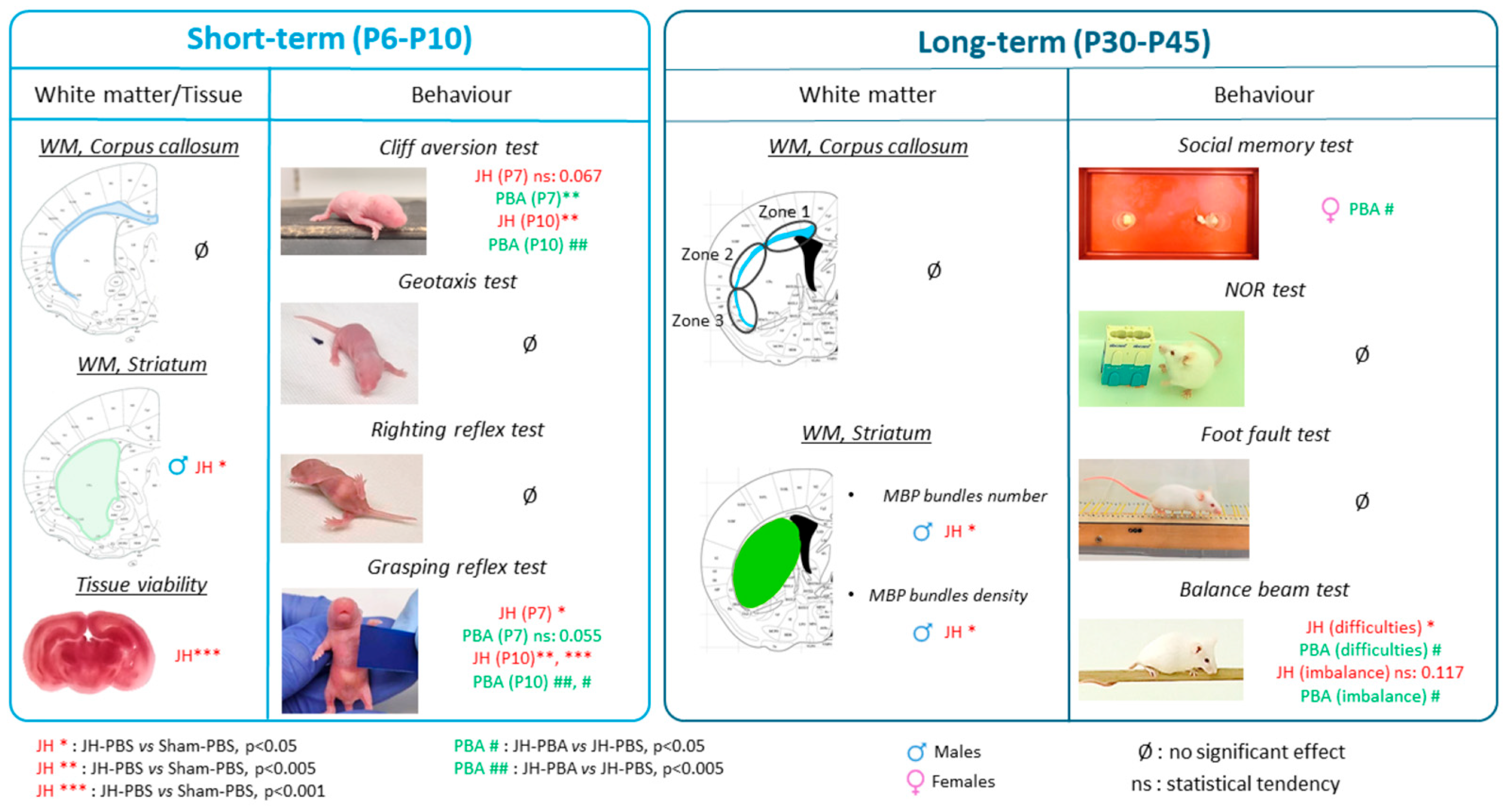

2. Results

2.1. Short-Term Weight Monitoring (Figure S1)

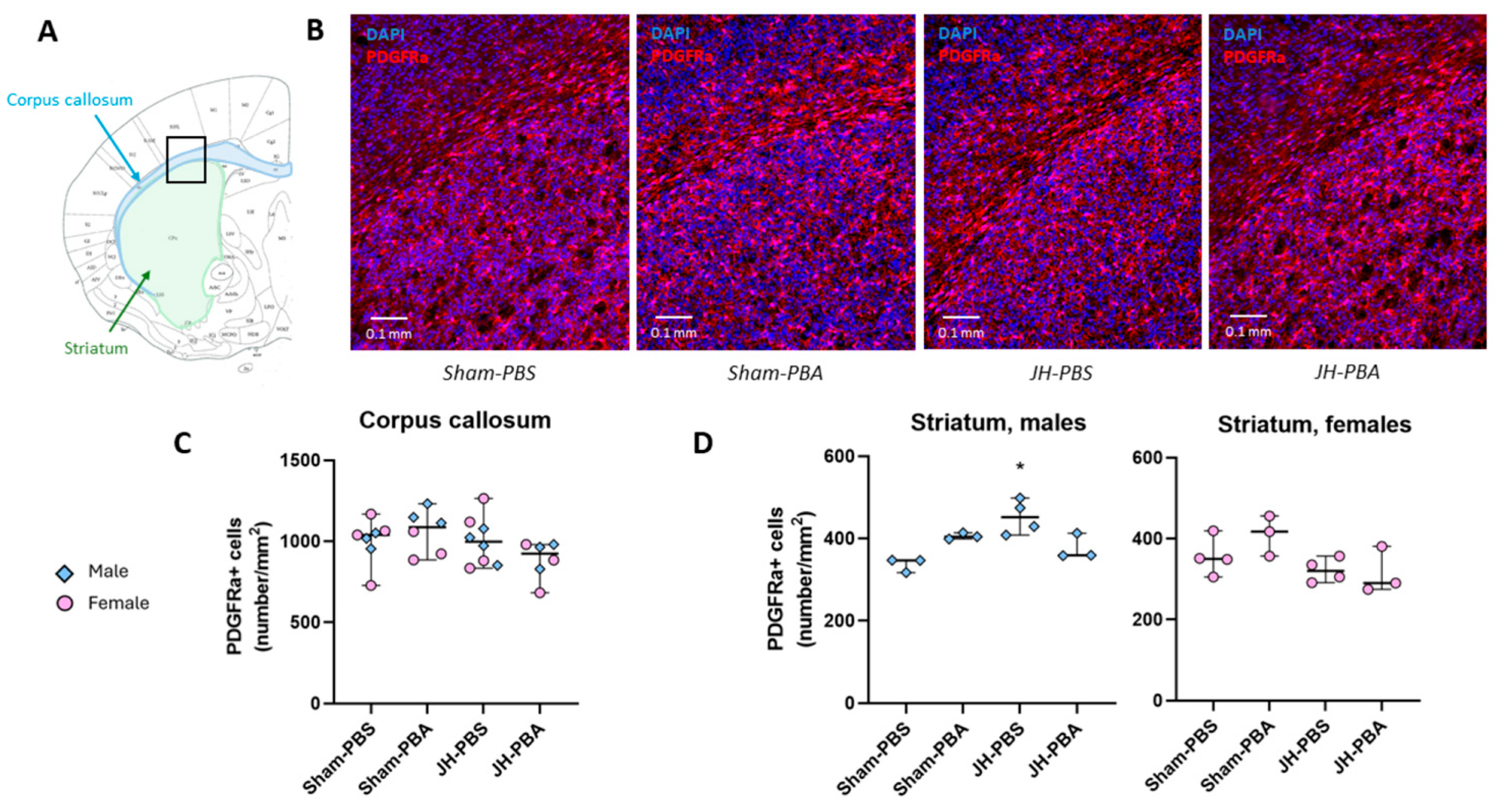

2.2. Short-Term Study of Cerebral White Matter and Tissular Integrity

2.2.1. PDGFRa Immunolabelling (P6)

2.2.2. TTC Staining (P10)

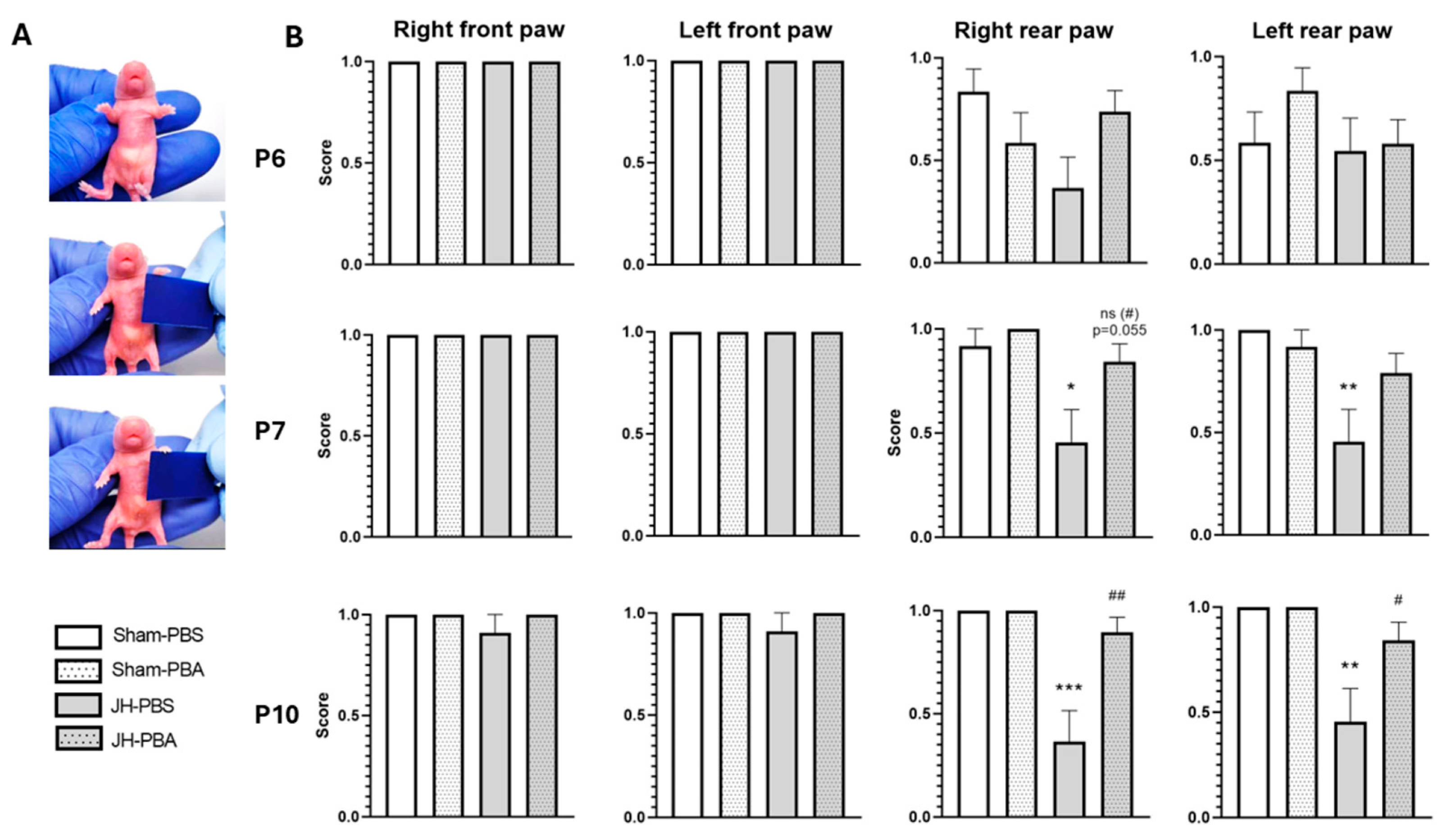

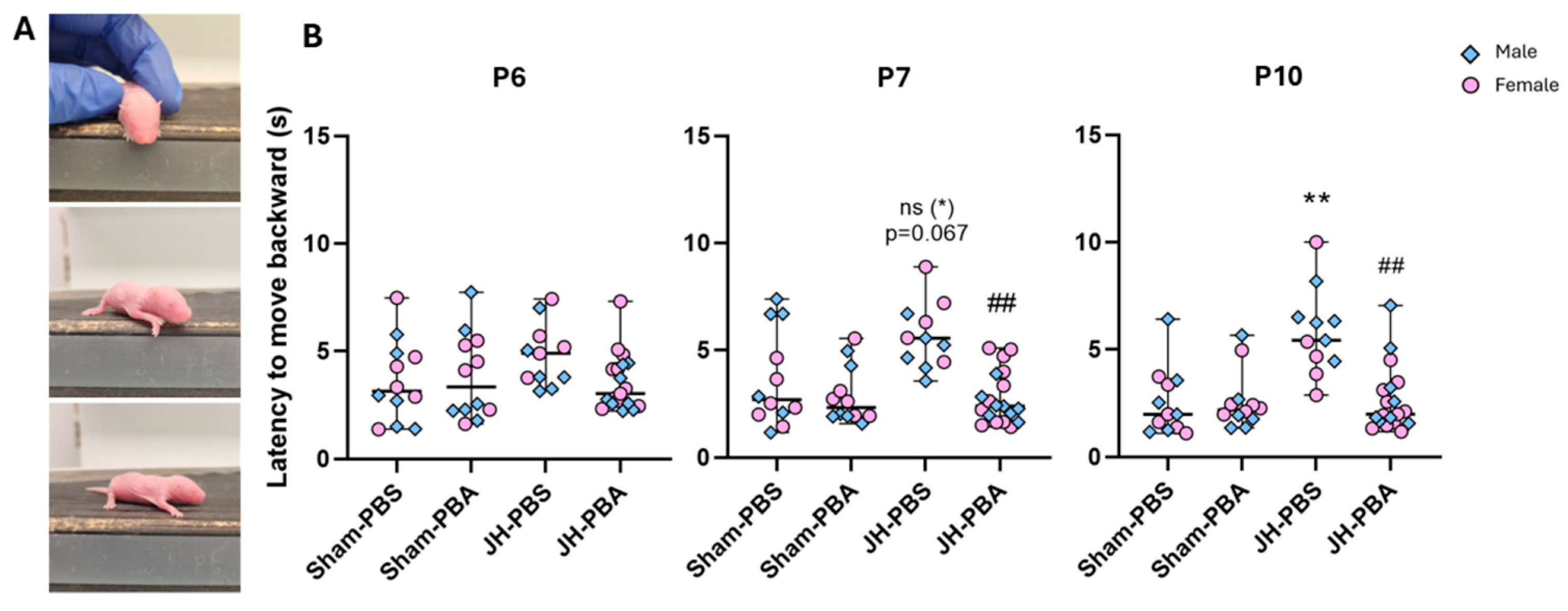

2.3. Short-Term Study of Behavior

2.3.1. Grasping Reflex Test (P6, P7, and P10)

2.3.2. Cliff Aversion Test (P6, P7 and P10)

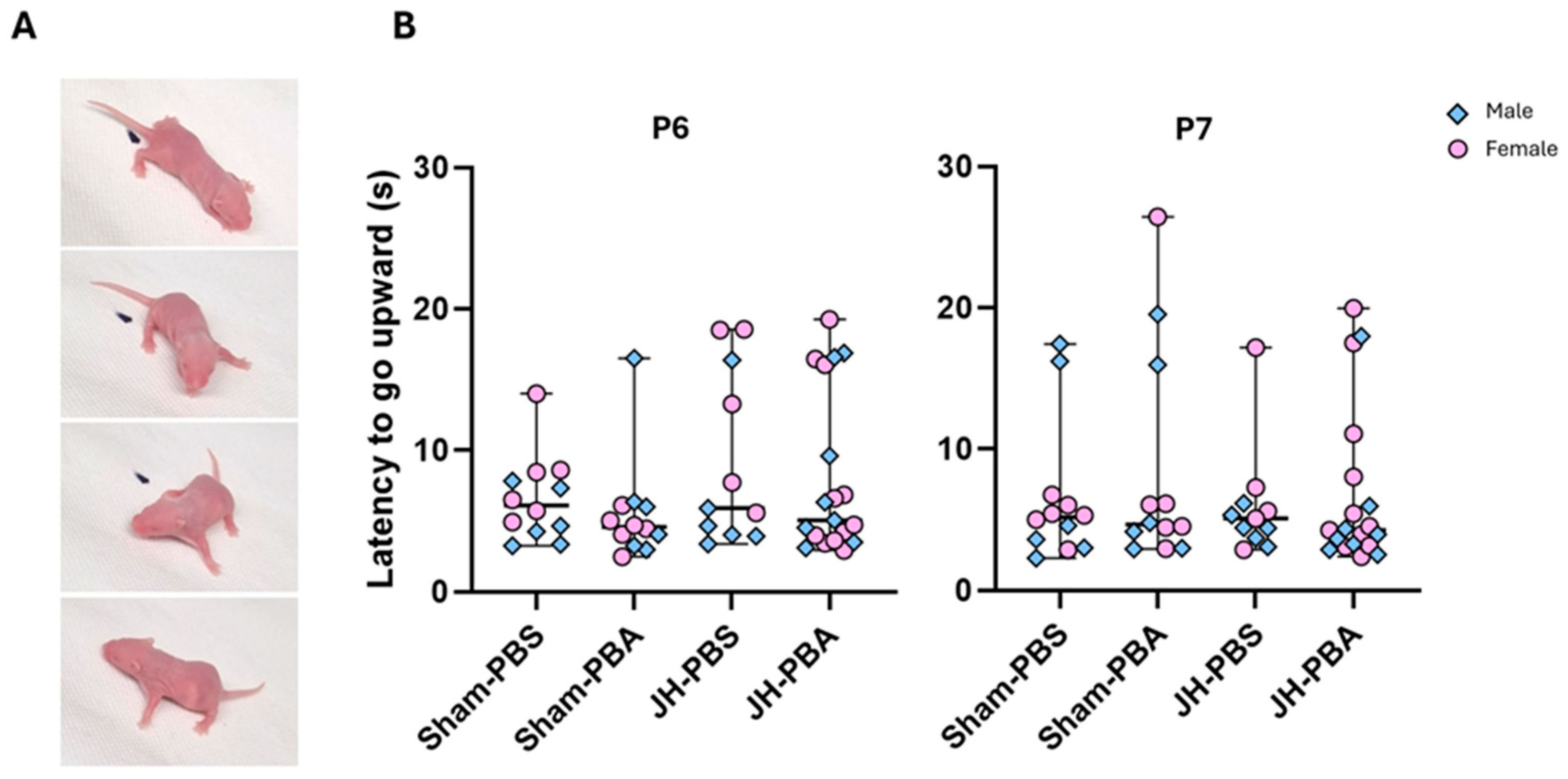

2.3.3. Negative Geotaxis Test (P6 and P7)

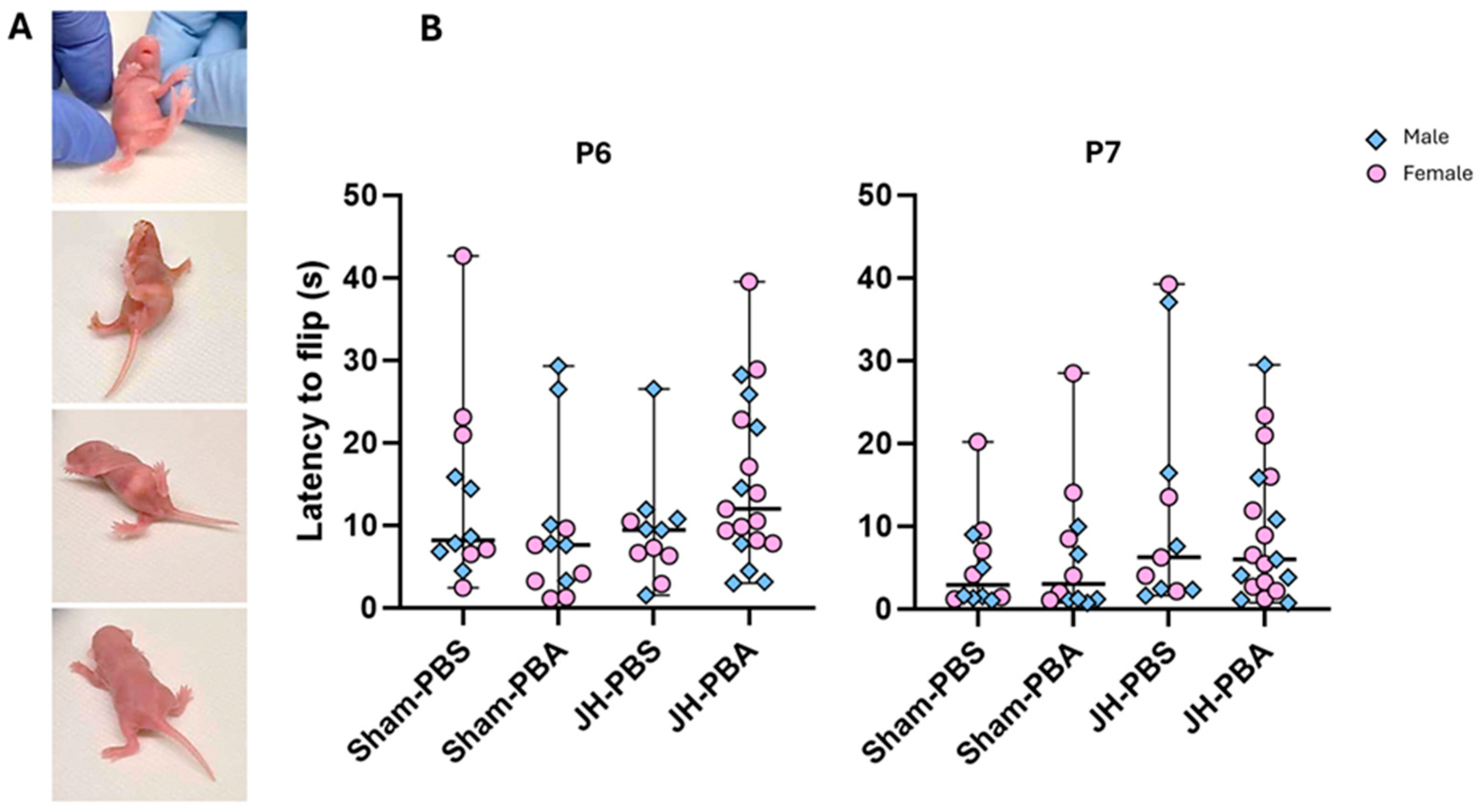

2.3.4. Righting Reflex Test (P6, P7)

2.4. Long-Term Study of White Matter (P45)

2.4.1. Study of White Matter in the Corpus Callosum (Figure 7)

2.4.2. Study of White Matter in the (Ventral) Striatum (Figure 8)

2.5. Long-Term Study of Behavior

2.5.1. Social Approach and Memory Test (P30 and P31)

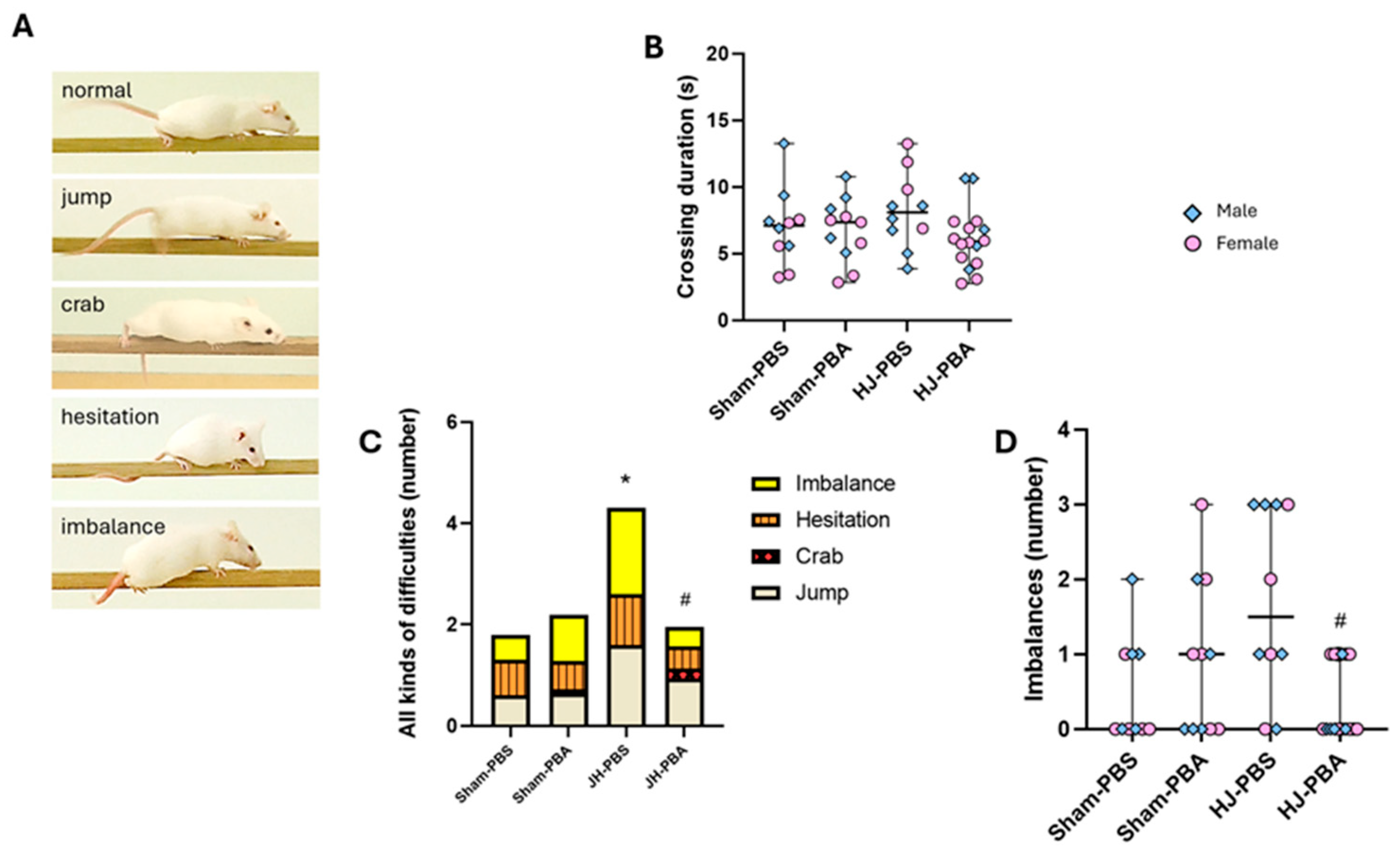

2.5.2. Balance Beam Test (P32)

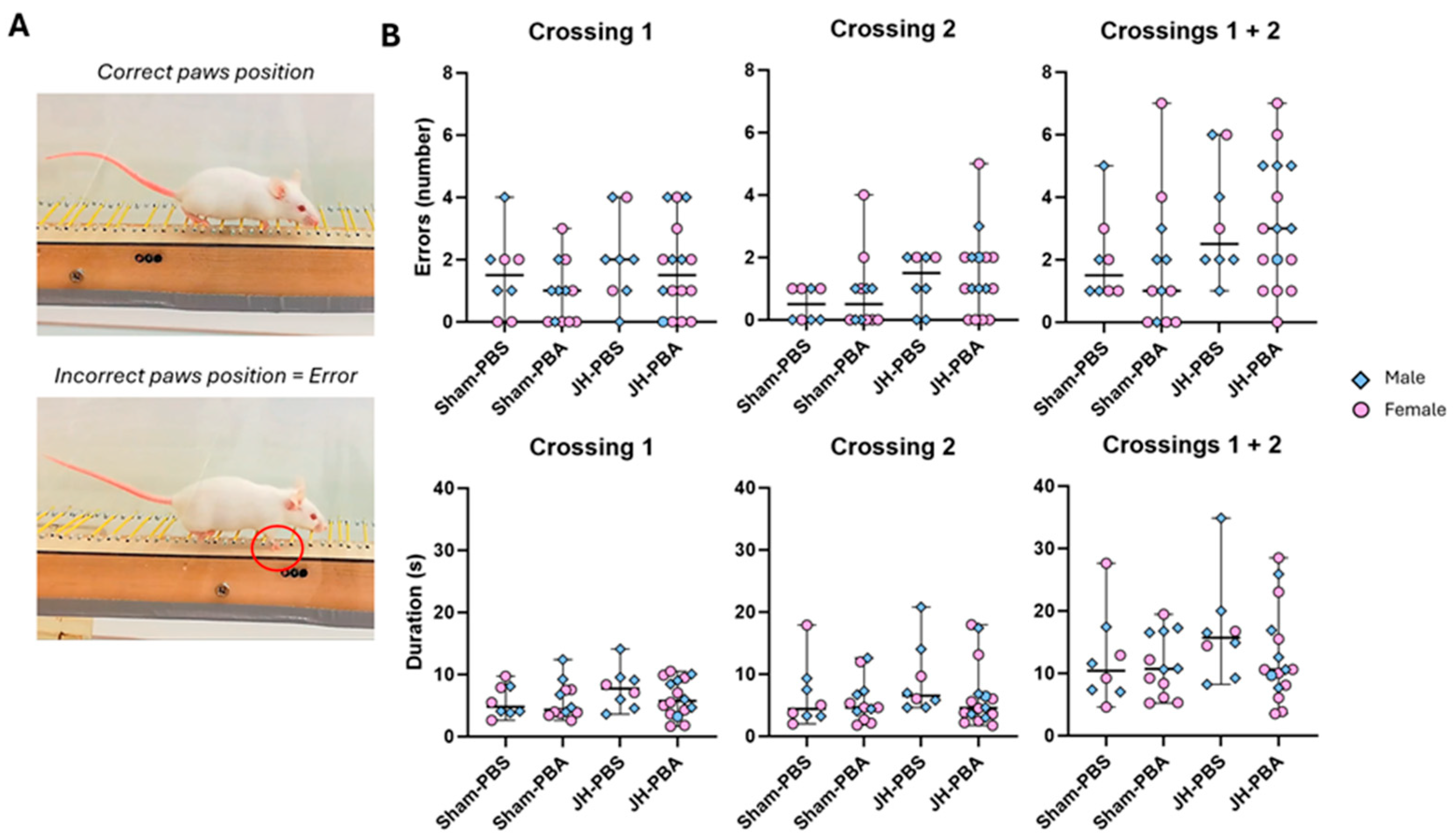

2.5.3. Foot-Fault Test (P33)

2.5.4. Novel Object Recognition Test (P34)

3. Discussion

3.1. Limitations of the Study

3.2. Conclusions

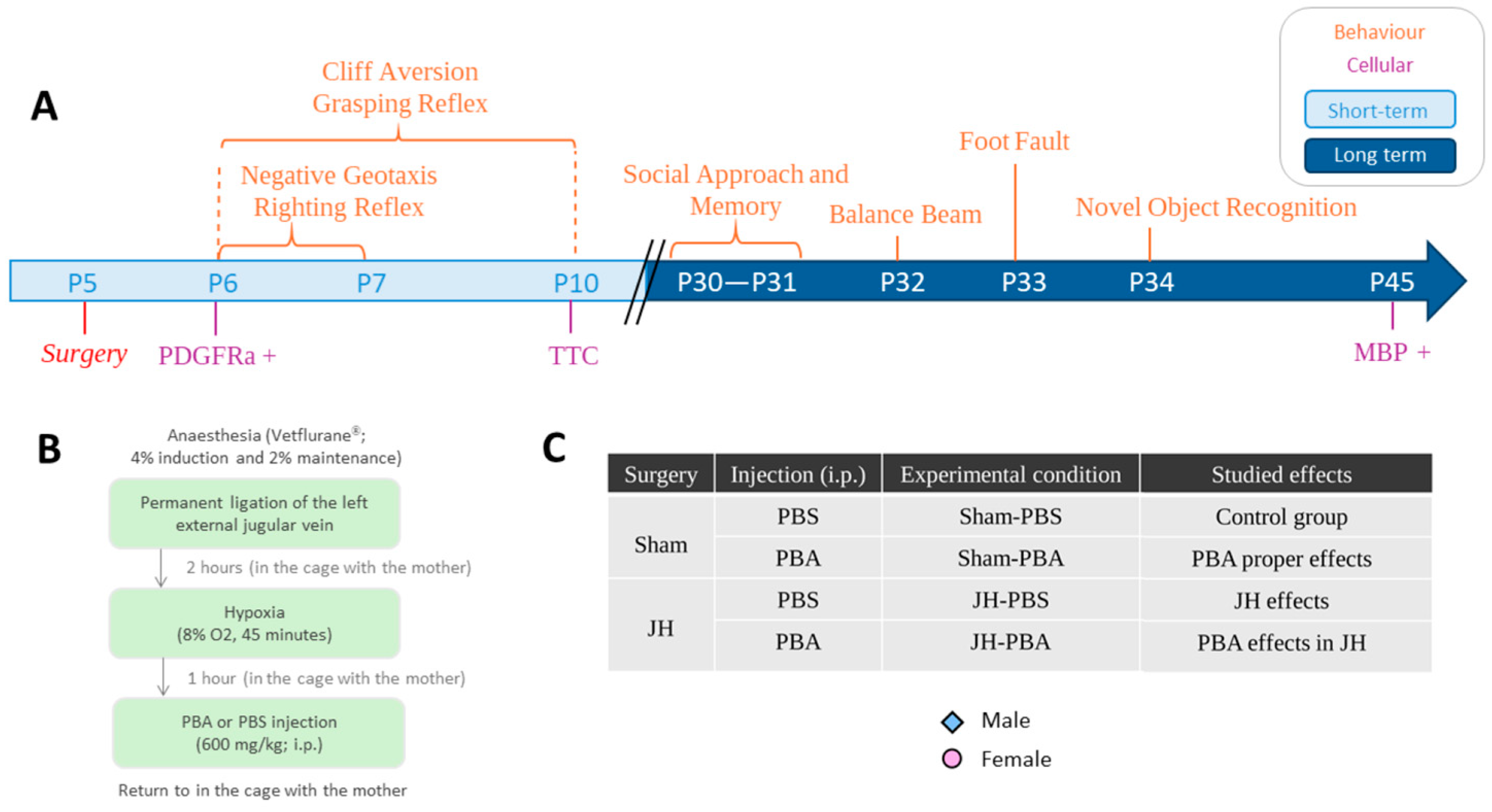

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Housing

4.2. The Jugular Hypoxia Model

4.3. Short-Term Weight Monitoring (P5–P10, Figure S1)

4.4. Short-Term Study of White Matter and Cerebral Tissue

4.4.1. PDGFRa Immunolabeling (P6; Figure 2)

4.4.2. TTC Staining (P10; Figure 3)

4.5. Short-Term Study of Sensorimotricity

4.5.1. Grasping Reflex Test (P6, P7, and P10; Figure 4)

4.5.2. Cliff Aversion Test (P6, P7, and P10; Figure 5)

4.5.3. Negative Geotaxis Test (P6 and P7; Figure 6)

4.5.4. Righting Reflex Test (P6, P7; Figure 7)

4.6. Long-Term Study of White Matter

MBP Immunolabeling (P45; Figure 8 and Figure 9)

4.7. Long-Term Study of Sensorimotor and Cognitive Abilities

4.7.1. Social Approach and Memory Test (P30 and P31; Figure 10)

4.7.2. Balance Beam Test (P32; Figure 11)

4.7.3. Foot-Fault Test (P33; Figure 12)

4.7.4. Novel Object Recognition Test (P34; Figure 14)

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CC | Corpus callosum |

| JH model | Jugular Hypoxia model |

| MBP | Myelin basic protein |

| NA | Not applicable |

| NOR test | Novel object recognition test |

| OL | Oligodendrocyte |

| P5 | Postnatal day 5 |

| PA | Perinatal asphyxia |

| PBA | Sodium Phenylbutyrate |

| PDGFRa | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha |

| WMI | White matter injury |

References

- van Tilborg, E.; de Theije, C.G.M.; van Hal, M.; Wagenaar, N.; de Vries, L.S.; Benders, M.J.; Rowitch, D.H.; Nijboer, C.H. Origin and Dynamics of Oligodendrocytes in the Developing Brain: Implications for Perinatal White Matter Injury. Glia 2018, 66, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Steenwinckel, J.; Bokobza, C.; Laforge, M.; Shearer, I.K.; Miron, V.E.; Rua, R.; Matta, S.M.; Hill-Yardin, E.L.; Fleiss, B.; Gressens, P. Key Roles of Glial Cells in the Encephalopathy of Prematurity. Glia 2024, 72, 475–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, S.A. Brain Injury in the Preterm Infant: New Horizons for Pathogenesis and Prevention. Pediatr. Neurol. 2015, 53, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertsson, A.-M.; Zhang, X.; Leavenworth, J.; Bi, D.; Nair, S.; Qiao, L.; Hagberg, H.; Mallard, C.; Cantor, H.; Wang, X. The Effect of Osteopontin and Osteopontin-Derived Peptides on Preterm Brain Injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Dieu-Lugon, B.; Dupré, N.; Legouez, L.; Leroux, P.; Gonzalez, B.J.; Marret, S.; Leroux-Nicollet, I.; Cleren, C. Why Considering Sexual Differences Is Necessary When Studying Encephalopathy of Prematurity through Rodent Models. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2020, 52, 2560–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, R.J.; Oh, W. Respiratory Distress in Newborns. Clin. Perinatol. 1978, 5, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermansen, C.L.; Lorah, K.N. Respiratory Distress in the Newborn. Am. Fam. Physician 2007, 76, 987–994. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.-H.; Chu, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, R.-B.; Iwata, O.; Huang, C.-C. Early-Life Respiratory Trajectories and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Infants Born Very and Extremely Preterm: A Retrospective Study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 64, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, C.; August, D.; Cobbald, L.; Lack, G.; Takashima, M.; Foxcroft, K.; Marsh, N.; Smith, P.; New, K.; Koorts, P.; et al. Neonatal Vascular Access Practice and Complications: An Observational Study of 1375 Catheter Days. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2023, 37, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.K.; Ryu, J.-H.; Chun, J.-Y.; Lee, J.W.; Choi, J.-H.; Park, M.-S.; Kim, J.H.; Shin, M.; Seo, J.H.; Lee, S.K. Neonatal Central Venous Catheter Thrombosis: Diagnosis, Management and Outcome. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2014, 25, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibleur, Y.; Dobbelaere, D.; Barth, M.; Brassier, A.; Guffon, N. Results from a Nationwide Cohort Temporary Utilization Authorization (ATU) Survey of Patients in France Treated with Pheburane® (Sodium Phenylbutyrate) Taste-Masked Granules. Paediatr. Drugs 2014, 16, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS). Evaluation Report: Pheburane® (Sodium Phenylbutyrate). Opinion Issued. 2014. Available online: https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_1720968/fr/pheburane-phenylbutyrate-de-sodium (accessed on 22 January 2014).

- Yang, G.; Peng, X.; Hu, Y.; Lan, D.; Wu, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, L. 4-Phenylbutyrate Benefits Traumatic Hemorrhagic Shock in Rats by Attenuating Oxidative Stress, Not by Attenuating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, e477–e491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Hosoi, T.; Okuma, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Nomura, Y. Sodium 4-Phenylbutyrate Protects against Cerebral Ischemic Injury. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004, 66, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessler, E.B.; Chibane, F.L.; Wang, Z.; Chuang, D.-M. Potential Roles of HDAC Inhibitors in Mitigating Ischemia-Induced Brain Damage and Facilitating Endogenous Regeneration and Recovery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 5105–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patnala, R.; Arumugam, T.V.; Gupta, N.; Dheen, S.T. HDAC Inhibitor Sodium Butyrate-Mediated Epigenetic Regulation Enhances Neuroprotective Function of Microglia during Ischemic Stroke. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 6391–6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Ghosh, A.; Jana, A.; Liu, X.; Brahmachari, S.; Gendelman, H.E.; Pahan, K. Sodium Phenylbutyrate Controls Neuroinflammatory and Antioxidant Activities and Protects Dopaminergic Neurons in Mouse Models of Parkinson’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legouez, L.; Le Dieu-Lugon, B.; Feillet, S.; Riou, G.; Yeddou, M.; Plouchart, T.; Dourmap, N.; Le Ray, M.A.; Marret, S.; Gonzalez, B.J.; et al. Effects of MgSO4 Alone or Associated with 4-PBA on Behavior and White Matter Integrity in a Mouse Model of Cerebral Palsy: A Sex- and Time-Dependent Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabault, M.; Turpin, V.; Maisterrena, A.; Jaber, M.; Egloff, M.; Galvan, L. Cerebellar and Striatal Implications in Autism Spectrum Disorders: From Clinical Observations to Animal Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Armstrong, E.A.; Yager, J.Y. Neurodevelopmental Reflex Testing in Neonatal Rat Pups. J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 122, e55261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather-Schussler, D.N.; Ferguson, T.S. A Battery of Motor Tests in a Neonatal Mouse Model of Cerebral Palsy. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, 117, e53569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benezit, A.; Hertz-Pannier, L.; Dehaene-Lambertz, G.; Dubois, J. Le Corps Calleux: Sa Vie Précoce, Son Œuvre Tardive. In Les Malformations Congénitales—Diagnostic Anténatal et Devenir, Tome 6; Sauramps Medical: Montpellier, France, 2011; ISBN 9782840237563. [Google Scholar]

- Cum, M.; Santiago Pérez, J.A.; Wangia, E.; Lopez, N.; Wright, E.S.; Iwata, R.L.; Li, A.; Chambers, A.R.; Padilla-Coreano, N. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of How Social Memory Is Studied. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.N.; Carlisle, H.J.; Southwell, A.; Patterson, P.H. Assessment of Motor Balance and Coordination in Mice Using the Balance Beam. J. Vis. Exp. 2011, 49, e2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.A.; Schiavo, A.; Xavier, L.L.; Mestriner, R.G. The Foot Fault Scoring System to Assess Skilled Walking in Rodents: A Reliability Study. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 892010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueptow, L.M. Novel Object Recognition Test for the Investigation of Learning and Memory in Mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 126, e55718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxinos, G.; Halliday, G.; Watson, C.; Kassem, M.S. Atlas of the Developing Mouse Brain, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Tuong, C.M.; Zhang, Y.; Shields, C.B.; Guo, G.; Fu, H.; Gozal, D. Mouse Intermittent Hypoxia Mimicking Apnoea of Prematurity: Effects on Myelinogenesis and Axonal Maturation. J. Pathol. 2012, 226, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, H.; Balla, G.Y.; Demeter, K.; Sipos, E.; Buzás Kaizler, A.; Szegedi, V.; Mikics, É. Inflammatory Mechanisms Contribute to Long-Term Cognitive Deficits Induced by Perinatal Asphyxia via Interleukin 1. Neuropsychopharmacology 2025, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, B.L.; Huang, A.; Kunjamma, R.B.; Solanki, A.; Popko, B. The Integrated Stress Response in Hypoxia-Induced Diffuse White Matter Injury. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 7465–7480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, C.; Sosunov, S.; Niatsetskaya, Z.; Isler, J.A.; Utkina Sosunova, I.; Jang, I.; Ratner, V.; Ten, V. Mild Intermittent Hypoxemia in Neonatal Mice Causes Permanent Neurofunctional Deficit and White Matter Hypomyelination. Exp. Neurol. 2015, 264, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, S. Hypoxia Inducible Factor and Diffuse White Matter Injury in the Premature Brain: Perspectives from Genetic Studies in Mice. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, L.; Qu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, T.; Zhao, F.; Tang, J.; Mu, D. Histone Acetylation of Oligodendrocytes Protects against White Matter Injury Induced by Inflammation and Hypoxia-Ischemia through Activation of BDNF-TrkB Signaling Pathway in Neonatal Rats. Brain Res. 2018, 1688, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, K.; Lückemann, L.; Klüver, V.; Thavaneetharajah, S.; Höber, D.; Bendix, I.; Fandrey, J.; Bertsche, A.; Felderhoff-Müser, U. Dose-Dependent Effects of Levetiracetam after Hypoxia and Hypothermia in the Neonatal Mouse Brain. Brain Res. 2016, 1646, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trollmann, R.; Richter, M.; Jung, S.; Walkinshaw, G.; Brackmann, F. Pharmacologic Stabilization of Hypoxia-Inducible Transcription Factors Protects Developing Mouse Brain from Hypoxia-Induced Apoptotic Cell Death. Neuroscience 2014, 278, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbier, P.; Edwards, D.A.; Roffi, J. The Neonatal Testosterone Surge: A Comparative Study. Arch. Int. Physiol. Biochim. Biophys. 1992, 100, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanaan, A.; Farahani, R.; Douglas, R.M.; Lamanna, J.C.; Haddad, G.G. Effect of Chronic Continuous or Intermittent Hypoxia and Reoxygenation on Cerebral Capillary Density and Myelination. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006, 290, R1105–R1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darnall, R.A.; Chen, X.; Nemani, K.V.; Sirieix, C.M.; Gimi, B.; Knoblach, S.; McEntire, B.L.; Hunt, C.E. Early Postnatal Exposure to Intermittent Hypoxia in Rodents Is Proinflammatory, Impairs White Matter Integrity, and Alters Brain Metabolism. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 82, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkovich, A.J.; Lyon, G.; Evrard, P. Formation, Maturation, and Disorders of White Matter. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1992, 13, 447–461. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy, B.; Darlington, R.B.; Finlay, B.L. Translating Developmental Time Across Mammalian Species. Neuroscience 2001, 105, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiane, A.; Schepers, M.; Rombaut, B.; Hupperts, R.; Prickaerts, J.; Hellings, N.; van den Hove, D.; Vanmierlo, T. From OPC to Oligodendrocyte: An Epigenetic Journey. Cells 2019, 8, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi Ghanem, C.; Degerny, C.; Hussain, R.; Liere, P.; Pianos, A.; Tourpin, S.; Habert, R.; Macklin, W.B.; Schumacher, M.; Ghoumari, A.M. Long-Lasting Masculinizing Effects of Postnatal Androgens on Myelin Governed by the Brain Androgen Receptor. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1007049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, F.; Wei, Y.; Balkaya, M.; Tikka, S.; Mandeville, J.B.; Waeber, C.; Moskowitz, M.A. Recognition Memory Impairments after Subcortical White Matter Stroke in Mice. Stroke 2014, 45, 1468–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, C.; Ling, E.A. Periventricular White Matter Damage in the Hypoxic Neonatal Brain: Role of Microglial Cells. Prog. Neurobiol. 2009, 87, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Le Ray, M.-A.; Larralde, C.; Legouez, L.; Marret, S.; Muller, J.-B.; Gonzalez, B.J.; Cleren, C. Short- and Long-Term Effects of Sodium Phenylbutyrate on White Matter and Sensorimotor and Cognitive Behavior in a Mild Murine Model of Encephalopathy of Prematurity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12099. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412099

Le Ray M-A, Larralde C, Legouez L, Marret S, Muller J-B, Gonzalez BJ, Cleren C. Short- and Long-Term Effects of Sodium Phenylbutyrate on White Matter and Sensorimotor and Cognitive Behavior in a Mild Murine Model of Encephalopathy of Prematurity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12099. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412099

Chicago/Turabian StyleLe Ray, Marie-Anne, Cyann Larralde, Lou Legouez, Stéphane Marret, Jean-Baptiste Muller, Bruno J. Gonzalez, and Carine Cleren. 2025. "Short- and Long-Term Effects of Sodium Phenylbutyrate on White Matter and Sensorimotor and Cognitive Behavior in a Mild Murine Model of Encephalopathy of Prematurity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12099. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412099

APA StyleLe Ray, M.-A., Larralde, C., Legouez, L., Marret, S., Muller, J.-B., Gonzalez, B. J., & Cleren, C. (2025). Short- and Long-Term Effects of Sodium Phenylbutyrate on White Matter and Sensorimotor and Cognitive Behavior in a Mild Murine Model of Encephalopathy of Prematurity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12099. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412099