Protective Effects of Arecoline on LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglial Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

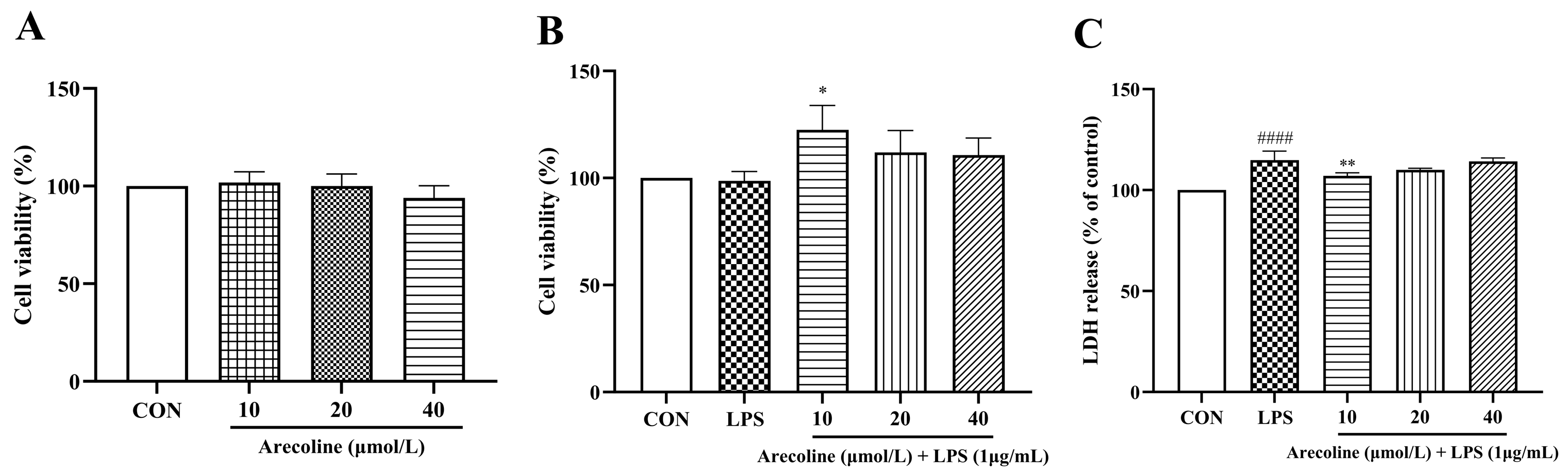

2.1. Effects of LPS on Microglial Viability and NO Production, and Cytotoxicity Assessment of Arecoline

2.2. Arecoline Maintains BV2 Microglial Viability and Reduces LPS-Induced Cytotoxicity

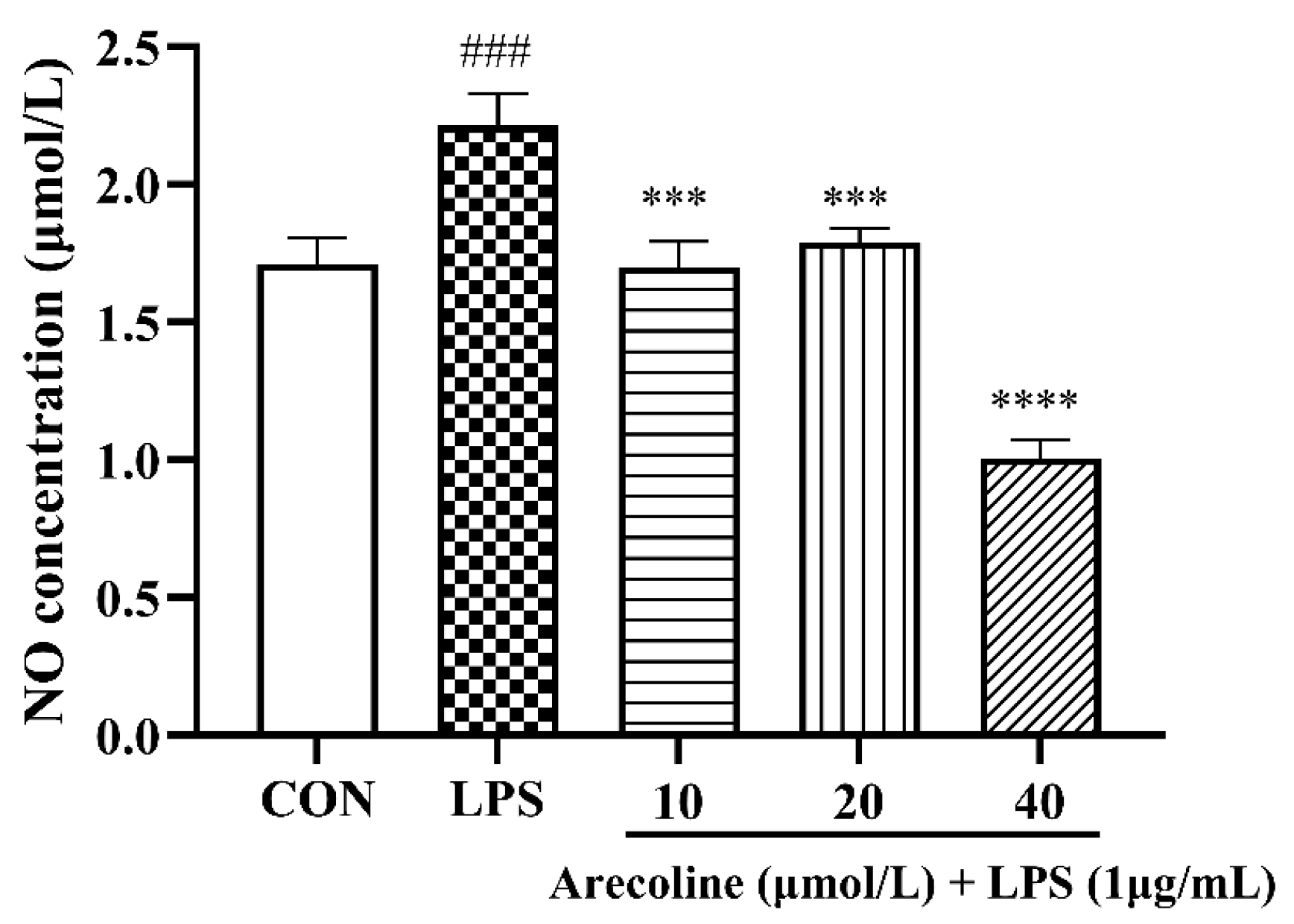

2.3. Arecoline Attenuates LPS-Stimulated Nitric Oxide Production in BV2 Microglia

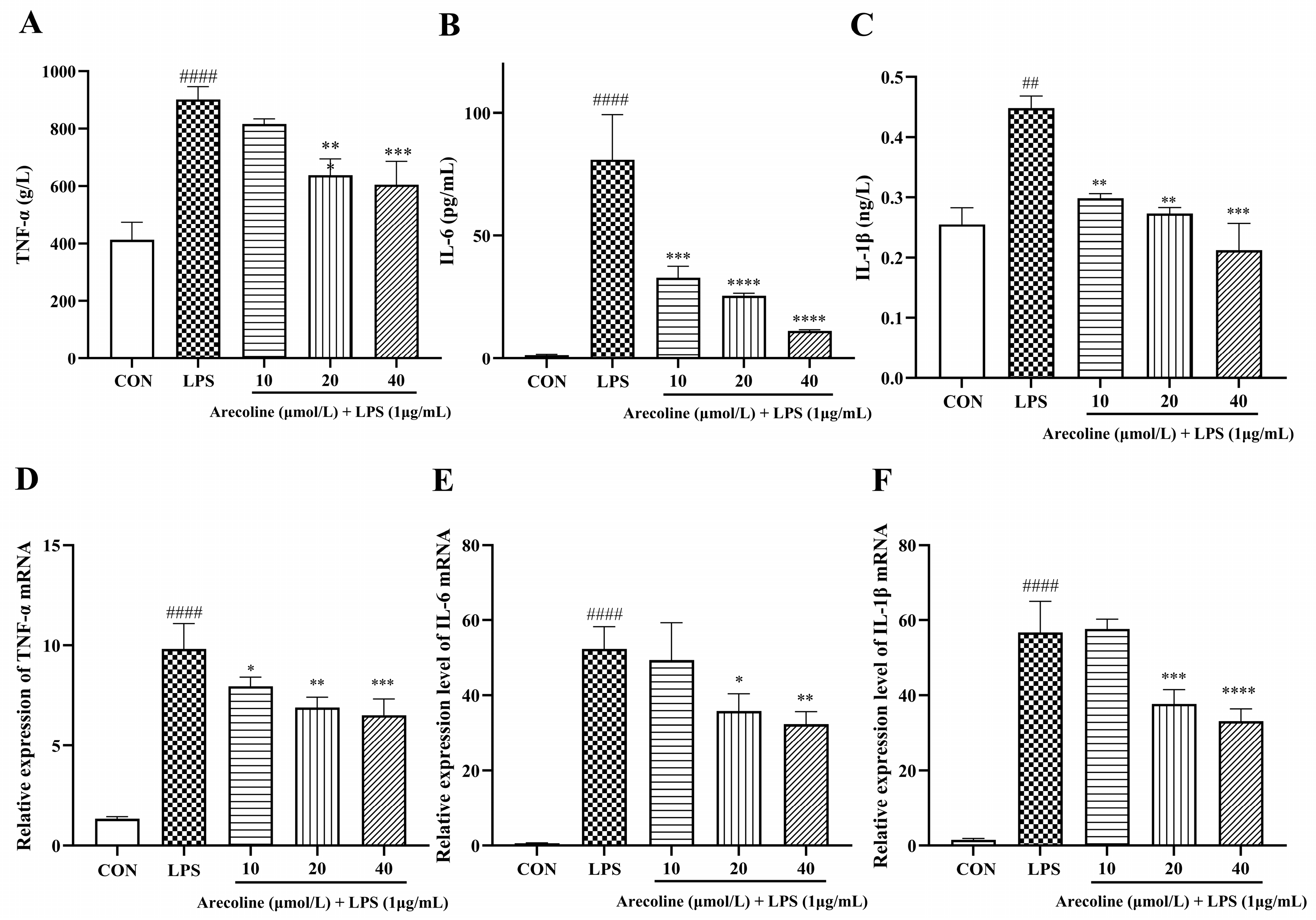

2.4. Effect of Arecoline on LPS-Induced Inflammatory Cytokine Release in BV2 Cells

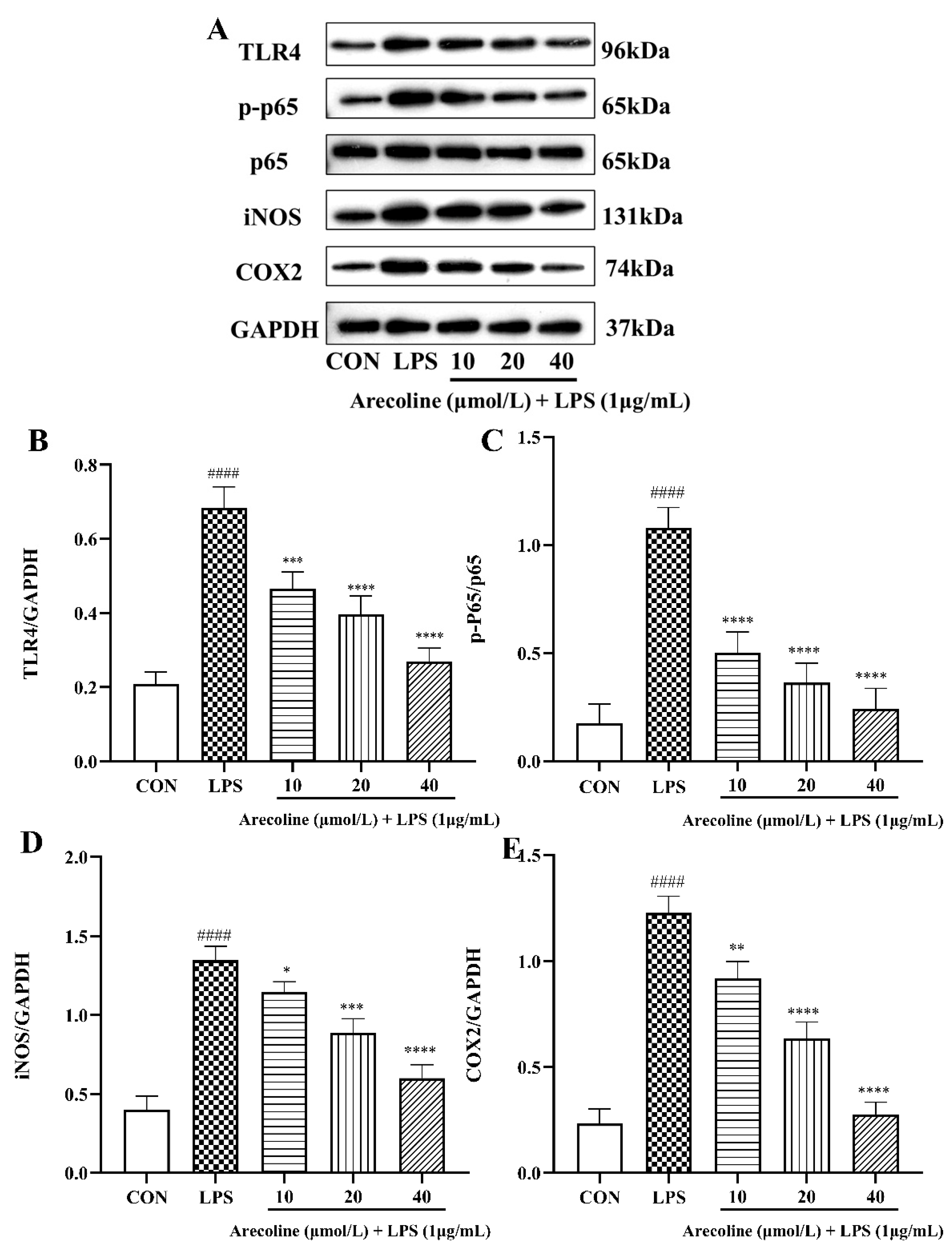

2.5. Effect of Arecoline on LPS-Induced TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway Proteins in BV2 Cells

2.6. Effect of Arecoline on LPS-Induced PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway Proteins in BV2 Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Equipment

4.2. Culture Conditions and Experimental Procedures

4.3. Determination of Cell Viability Using the CCK-8

4.4. Determination of NO Generation

4.5. Quantification of Cytokines Using ELISA

4.6. Determination of mRNA Expression by Quantitative Real-Time PCR

4.7. Protein Expression Analysis by Western Blotting

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle MediumDulbecco |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic acid |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| qPCR | Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| NF-κB p65 | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells p65 subunit |

| p-p65 | Phosphorylated NF-κB p65 |

| PI3K p85 | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulatory subunit p85 |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| p-AKT | Phosphorylated AKT |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

References

- Wang, W.Y.; Tan, M.S.; Yu, J.T.; Tan, L. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2015, 3, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, D.; Mao, Q.; Xia, H. Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration development. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M.; Zecca, L.; Hong, J.-S.; Block, M.L.; Zecca, L.; Hong, J.S. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: Uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzio, L.; Viotti, A.; Martino, G. Microglia in Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration: From Understanding to Therapy. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 742065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.Z.; Zou, C.J.; Mei, X.; Li, X.F.; Luo, H.; Shen, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, X.X.; Wu, L.; Liu, Y. Targeting neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: From mechanisms to clinical applications. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, R.J.; Avramopoulos, D.; Jantzie, L.L.; McCallion, A.S. Neuroinflammation represents a common theme amongst genetic and environmental risk factors for Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassaghi, Y.; Nazerian, Y.; Ghasemi, M.; Nazerian, A.; Sayehmiri, F.; Perry, G.; Gholami Pourbadie, H. Microglial modulation as a therapeutic strategy in Alzheimer’s disease: Focus on microglial preconditioning approaches. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransohoff, R.M.; Perry, V.H. Microglial Physiology: Unique Stimuli, Specialized Responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 27, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Ma, Z.; Chen, X.; Shu, S. Microglia activation in central nervous system disorders: A review of recent mechanistic investigations and development efforts. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1103416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.M.; Rodríguez, J.; Giambartolomei, G.H. Microglia at the Crossroads of Pathogen-Induced Neuroinflammation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 14, 17590914221104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Itriago, A.; Radford, R.A.W.; Aramideh, J.A.; Maurel, C.; Scherer, N.M.; Don, E.K.; Lee, A.; Chung, R.S.; Graeber, M.B.; Morsch, M. Microglia morphophysiological diversity and its implications for the CNS. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 997786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Jiang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, S. Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, K. Microglia mediated neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases: A review on the cell signaling pathways involved in microglial activation. J. Neuroinflamm. 2023, 383, 578180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Liu, M.-Y.; Zhang, D.-F.; Zhong, X.; Du, K.; Qian, P.; Yao, W.-F.; Gao, H.; Wei, M.-J. Baicalin mitigates cognitive impairment and protects neurons from microglia-mediated neuroinflammation via suppressing NLRP3 inflammasomes and TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2019, 25, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmerman, R.; Burm, S.M.; Bajramovic, J.J. An Overview of in vitro Methods to Study Microglia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrzypczak-Wiercioch, A.; Sałat, K. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Model of Neuroinflammation: Mechanisms of Action, Research Application and Future Directions for Its Use. Molecules 2022, 27, 5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lively, S.; Schlichter, L.C. Microglia Responses to Pro-inflammatory Stimuli (LPS, IFNγ+TNFα) and Reprogramming by Resolving Cytokines (IL-4, IL-10). Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, N.; Moon, E.H.; Kim, H.W.; Hong, J.; Beutler, J.A.; Sung, S.H. Inhibition of Nitric Oxide Production in BV2 Microglial Cells by Triterpenes from Tetrapanax papyriferus. Molecules 2016, 21, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima, E.P.; Laurindo, L.F.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Direito, R.; Tanaka, M.; Jasmin Santos German, I.; Lamas, C.B.; Guiguer, E.L.; Araújo, A.C.; Fiorini, A.M.R.; et al. Polyphenols, Alkaloids, and Terpenoids Against Neurodegeneration: Evaluating the Neuroprotective Effects of Phytocompounds Through a Comprehensive Review of the Current Evidence. Metabolites 2025, 15, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.U.; Wali, A.F.; Ahmad, A.; Shakeel, S.; Rasool, S.; Ali, R.; Rashid, S.M.; Madkhali, H.; Ganaie, M.A.; Khan, R. Neuroprotective Strategies for Neurological Disorders by Natural Products: An update. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.W.; Lee, J.-E.; Lee, C.; Kim, Y.T. Natural Products and Their Neuroprotective Effects in Degenerative Brain Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryal, B.; Raut, B.K.; Bhattarai, S.; Bhandari, S.; Tandan, P.; Gyawali, K.; Sharma, K.; Ranabhat, D.; Thapa, R.; Aryal, D.; et al. Potential Therapeutic Applications of Plant-Derived Alkaloids against Inflammatory and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 7299778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Zeng, D.; Liang, T.; Liu, Y.; Cui, F.; Zhao, H.; Lu, W. Recent Advance on Biological Activity and Toxicity of Arecoline in Edible Areca (Betel) Nut: A Review. Foods 2024, 13, 3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Xu, Z.; Cao, F.; Yuan, Q.; Su, W.; Huang, Z. Arecoline alleviates autism spectrum disorder-like behaviors and cognition disorders in a valproic acid mouse model by activating the AMPK/CREB/BDNF signaling pathway. Brain Res. Bull. 2025, 229, 111431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Li, W.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J. Arecoline Alleviates Depression via Gut-Brain Axis Modulation, Neurotransmitter Balance, Neuroplasticity Enhancement, and Inflammation Reduction in CUMS Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 10201–10213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhuo, M. Inhibition of cortical synaptic transmission, behavioral nociceptive, and anxiodepressive-like responses by arecoline in adult mice. Mol. Brain 2024, 17, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, M.; Hao, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, C. Neuroinflammation mechanisms of neuromodulation therapies for anxiety and depression. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Zhang, J. Neuroinflammation, memory, and depression: New approaches to hippocampal neurogenesis. J. Neuroinflamm. 2023, 20, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yu, W.; Li, H.; Hu, X.; Wang, X. Bioactive Components of Areca Nut: An Overview of Their Positive Impacts Targeting Different Organs. Nutrients 2024, 16, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, F.; Hu, X.; Wang, X. Review of the toxic effects and health functions of arecoline on multiple organ systems. Food Innov. Adv. 2024, 3, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensaensuk, V.; Huang, B.R.; Huang, S.T.; Lin, C.; Xie, S.Y.; Chen, C.W.; Chen, Y.C.; Cheng, H.T.; Liu, Y.S.; Lai, S.W.; et al. LPS priming-induced immune tolerance mitigates LPS-stimulated microglial activation and social avoidance behaviors in mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 154, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fołta, J.; Rzepka, Z.; Wrześniok, D. The Role of Inflammation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Parkinson’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Sun, M.; Yang, H. Microglia in the Neuroinflammatory Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Therapeutic Targets. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 856376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lull, M.E.; Block, M.L. Microglial Activation and Chronic Neurodegeneration. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liy, P.M.; Puzi, N.N.A.; Jose, S.; Vidyadaran, S. Nitric oxide modulation in neuroinflammation and the role of mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 246, 2399–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo, A.F.O.; Suemoto, C.K. The modulation of neuroinflammation by inducible nitric oxide synthase. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 16, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üremiş, N.; Üremiş, M.M. Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress, Apoptosis, and Redox Signaling: Key Players in Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2025, 39, e70133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuste, J.E.; Tarragon, E.; Campuzano, C.M.; Ros-Bernal, F. Implications of glial nitric oxide in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.E.; Lee, J.S. Advances in the Regulation of Inflammatory Mediators in Nitric Oxide Synthase: Implications for Disease Modulation and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, M.T.; Saso, L.; Farina, M. LPS-Activated Microglial Cell-Derived Conditioned Medium Protects HT22 Neuronal Cells against Glutamate-Induced Ferroptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Choi, S.Y.; Yoo, G.; Park, H.Y.; Choi, I.W.; Hur, J. Melissa officinalis Regulates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced BV2 Microglial Activation via MAPK and Nrf2 Signaling. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 2474–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, R.N.; Pahan, K. Regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene in glial cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006, 8, 929–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinelli, M.A.; Do, H.T.; Miley, G.P.; Silverman, R.B. Inducible nitric oxide synthase: Regulation, structure, and inhibition. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 158–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Das, A.; Ray, S.K.; Banik, N.L. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res. Bull. 2012, 87, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M.L.; Hong, J.S. Microglia and inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration: Multiple triggers with a common mechanism. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005, 76, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, F.R.; Musella, A.; De Vito, F.; Fresegna, D.; Bullitta, S.; Vanni, V.; Guadalupi, L.; Stampanoni Bassi, M.; Buttari, F.; Mandolesi, G.; et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor and Interleukin-1β Modulate Synaptic Plasticity during Neuroinflammation. Neural Plast. 2018, 2018, 8430123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goshi, N.; Lam, D.; Bogguri, C.; George, V.K.; Sebastian, A.; Cadena, J.; Leon, N.F.; Hum, N.R.; Weilhammer, D.R.; Fischer, N.O.; et al. Direct effects of prolonged TNF-α and IL-6 exposure on neural activity in human iPSC-derived neuron-astrocyte co-cultures. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1512591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yan, K.; Chen, F.; Huang, W.; Lv, B.; Sun, C.; Xu, L.; Li, F.; Jiang, X. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses of BV2 microglial cells through TSG-6. J. Neuroinflamm. 2014, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, D.; Jung, S.; Brackmann, F.; Richter-Kraus, M.; Trollmann, R. Hypoxia Potentiates LPS-Mediated Cytotoxicity of BV2 Microglial Cells In Vitro by Synergistic Effects on Glial Cytokine and Nitric Oxide System. Neuropediatrics 2015, 46, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.; Anderson, P. Post-transcriptional control of cytokine production. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossol, M.; Heine, H.; Meusch, U.; Quandt, D.; Klein, C.; Sweet, M.J.; Hauschildt, S. LPS-induced cytokine production in human monocytes and macrophages. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 31, 379–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shytle, R.; Mori, T.; Townsend, K.; Vendrame, M.; Sun, N.; Zeng, J.; Ehrhart, J.; Silver, A.; Tan, J. Cholinergic modulation of microglial activation by α7 nicotinic receptors. J. Neurochem. 2004, 89, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Azhar, G.; Zhang, X.; Patyal, P.; Kc, G.; Sharma, S.; Che, Y.; Wei, J.Y.P. gingivalis-LPS Induces Mitochondrial Dysfunction Mediated by Neuroinflammation through Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Azhar, G.; Patyal, P.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Wei, J.Y. Proteomic analysis of P. gingivalis-Lipopolysaccharide induced neuroinflammation in SH-SY5Y and HMC3 cells. Geroscience 2024, 46, 4315–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.; Azhar, G.; Patyal, P.; Zhang, X.; Wei, J.Y. Porphyromonas gingivalis-Lipopolysaccharide Induced Caspase-4 Dependent Noncanonical Inflammasome Activation Drives Alzheimer’s Disease Pathologies. Cells 2025, 14, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, C.R.A.; Gomes, G.F.; Candelario-Jalil, E.; Fiebich, B.L.; de Oliveira, A.C.P. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation as a Bridge to Understand Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Han, B.; Hai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, J.; Sun, D.; Yin, P. The Role of Microglia/Macrophages Activation and TLR4/NF-κB/MAPK Pathway in Distraction Spinal Cord Injury-Induced Inflammation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 926453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, X.; Shen, X.; Lin, M.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, J. NF-κB in biology and targeted therapy: New insights and translational implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Huang, C.; Qu, S.; Lin, H.; Zhong, H.-J.; Chong, C.-M. Oxyimperatorin attenuates LPS-induced microglial activation in vitro and in vivo via suppressing NF-κB p65 signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 173, 116379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.J.; Li, N.; Yu, L.; Chen, Z.Y.; Hua, R.; Qin, X.; Zhang, Y.M. Activation of BV2 microglia by lipopolysaccharide triggers an inflammatory reaction in PC12 cell apoptosis through a toll-like receptor 4-dependent pathway. Cell Stress Chaperones 2015, 20, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianciulli, A.; Porro, C.; Calvello, R.; Trotta, T.; Lofrumento, D.D.; Panaro, M.A. Microglia Mediated Neuroinflammation: Focus on PI3K Modulation. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, E.; Mychasiuk, R.; Hibbs, M.L.; Semple, B.D. Dysregulated phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling in microglia: Shaping chronic neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflamm. 2021, 18, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, M.E.; Cianciulli, A.; Monda, V.; Monda, M.; Filannino, F.M.; Antonucci, L.; Valenzano, A.; Cibelli, G.; Porro, C.; Messina, G.; et al. α-Tocopherol Protects Lipopolysaccharide-Activated BV2 Microglia. Molecules 2023, 28, 3340. [Google Scholar]

- Cianciulli, A.; Calvello, R.; Porro, C.; Trotta, T.; Salvatore, R.; Panaro, M.A. PI3k/Akt signalling pathway plays a crucial role in the anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin in LPS-activated microglia. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 36, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnardt, S. Innate immunity and neuroinflammation in the CNS: The role of microglia in Toll-like receptor-mediated neuronal injury. Glia 2010, 58, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Wang, Y.; Feng, D.-C.; Xiao, B.-G.; Xu, L.-Y. Tetrandrine suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation by inhibiting NF-κB pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2008, 29, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Li, Y.; Hou, X.; Zhang, R.; Hu, S.; Wang, Y. Oxymatrine inhibits microglia activation via HSP60-TLR4 signaling. Biomed. Rep. 2016, 5, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Lin, Q.; Tan, J.-L.; Zhao, H.-Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, N.-H.; Wu, Z.-N.; Fan, C.-L.; Li, Y.-L.; Ding, W.-L.; et al. Water-soluble matrine-type alkaloids with potential anti-neuroinflammatory activities from the seeds of Sophora alopecuroides. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 116, 105337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Fu, S.; He, D.; Hu, G.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, B.; Du, J.; Zhou, A.; Su, Y.; et al. Evodiamine Inhibits Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced Inflammation in BV-2 Cells via Regulating AKT/Nrf2-HO-1/NF-κB Signaling Axis. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 41, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Gao, L.; Hou, W.; Wu, J. β-Sitosterol Alleviates Inflammatory Response via Inhibiting the Activation of ERK/p38 and NF-κB Pathways in LPS-Exposed BV2 Cells. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 7532306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, M.; Khoshbakht, T.; Jamali, E.; Kallenbach, J.; Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Baniahmad, A. Interaction between Non-Coding RNAs and Androgen Receptor with an Especial Focus on Prostate Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Forward Primer (5′→3′) | Reverse Primer (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | GAGATTACTGCTCTGGCTCCTA | GGACTCATCGTACTCCTGCTTG |

| TNF-α | TAACTTAGAAAGGGGATTATGGCT | TGGAAAGGTCTGAAGGTAGGAA |

| IL-6 | TTGCCTTCTTGGGACTGATG | ACTCTTTTCTCATTTCCACGATTT |

| IL-1β | TCACAAGCAGAGCACAAGCC | CATTAGAAACAGTCCAGCCCATAC |

| Antibody Target | Primary Antibody | Dilution Ratio | Molecular Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PI3K | 1:1000 | 85 kDa |

| 2 | p-AKT | 1:1000 | 60 kDa |

| 3 | AKT | 1:1000 | 60 kDa |

| 4 | p-p65 | 1:1000 | 65 kDa |

| 5 | p65 | 1:500 | 65 kDa |

| 6 | iNOS | 1:500 | 131 kDa |

| 7 | COX2 | 1:1000 | 74 kDa |

| 8 | TLR4 | 1:1000 | 96 kDa |

| 9 | GAPDH | 1:1000 | 37 kDa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Cui, J.; Sun, J.; Fan, B.; Wang, F.; Lu, C. Protective Effects of Arecoline on LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412097

Zhang X, Cui J, Sun J, Fan B, Wang F, Lu C. Protective Effects of Arecoline on LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglial Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412097

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xiangfei, Jingwen Cui, Jing Sun, Bei Fan, Fengzhong Wang, and Cong Lu. 2025. "Protective Effects of Arecoline on LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglial Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412097

APA StyleZhang, X., Cui, J., Sun, J., Fan, B., Wang, F., & Lu, C. (2025). Protective Effects of Arecoline on LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglial Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412097